1 Chapter 1: Introduction to College Writing at CNM

Part 1: Chapter 1

This textbook is a college reader for English 1110 and 1120, Composition I and Composition II, respectively. If you are enrolled in one of these courses, you may be nearing the end of your studies at Central New Mexico Community College (CNM), you may be just starting your studies at CNM, or you may have already taken this class but didn’t finish. The reality is every English 1110 and 1120 course at CNM contains a diverse range of students. If you are enrolled in English 1110 or 1120 at CNM, you are likely a resident of New Mexico. You might have gone to an elementary or secondary school here. You might feel like a part of the unique culture here in NM.

This textbook asks you to take yourself seriously as a college writer. You are entering the realm of academic writing; you are entering academia. Welcome. We are happy you are here. Being a CNM student means that you are enrolled at the largest post-secondary institution in the state of New Mexico.

The graphic below lists the outcomes for English 1110 and 1120. To pass English 1110 and 1120, you are required to obtain the following skills and knowledge. Every course at CNM is assessed based on its outcomes.

Did You Know

Being a CNM student means that you are enrolled at the largest post-secondary institution in the state.

CNM offers resources that can help you not only with your studies but also with managing your responsibilities as well. In this textbook, we’ll cover the conventions of writing, and we’ll also cover some of the resources available to you as a CNM student. And since this book is free and available on the internet, you can keep it…forever!

This textbook is an Open Educational Resource text, which means it was created using free and available sources on the Internet, namely seven different open access books. Our compiled textbook will shift between free, outside writing resources and the plural first pronoun voice, or the we voice, signaling the English teachers who compiled and developed sections of the text.

Throughout this text, the writers–all CNM English faculty, some of whom are still paying back student loans–are the we who compiled this textbook. We did so because we believe that a college education should be engaging, enlightening, informative, life-affirming, worldview-upturning and affordable. We believe it shouldn’t cost money to learn how to write, and that is why we are making this book available to you. This project also would not have happened without the support of CNM’s OER initiative and CHSS administration.

This textbook will cover ways to communicate effectively as you develop insight into your own style, writing process, grammatical choices, and rhetorical situations. With these skills, you should be able to improve your writing talent regardless of the discipline you enter after completing this course. Knowing your rhetorical situation, or the circumstances under which you communicate, and knowing which tone, style, and genre will most effectively persuade your audience, will help you regardless of whether you are enrolling in history, biology, theater, or music next semester–because when you get to college, you write in every discipline. To help launch our introduction this chapter includes a section from the open access textbook Successful Writing.

As you begin this chapter, you may wonder why you need an introduction. After all, you have been writing and reading since elementary school. You completed numerous assessments of your reading and writing skills in high school and as part of your application process for college. You may write on the job, too. Why is a college writing course even necessary?

It can be difficult to feel excited about an intro writing course when you are eager to begin the coursework in your major (and if you are an English major, let your teacher know so you can talk about your future education plans). Regardless of your field of study, honing your writing skills—plus your reading and critical-thinking skills—gives you a more solid academic foundation.

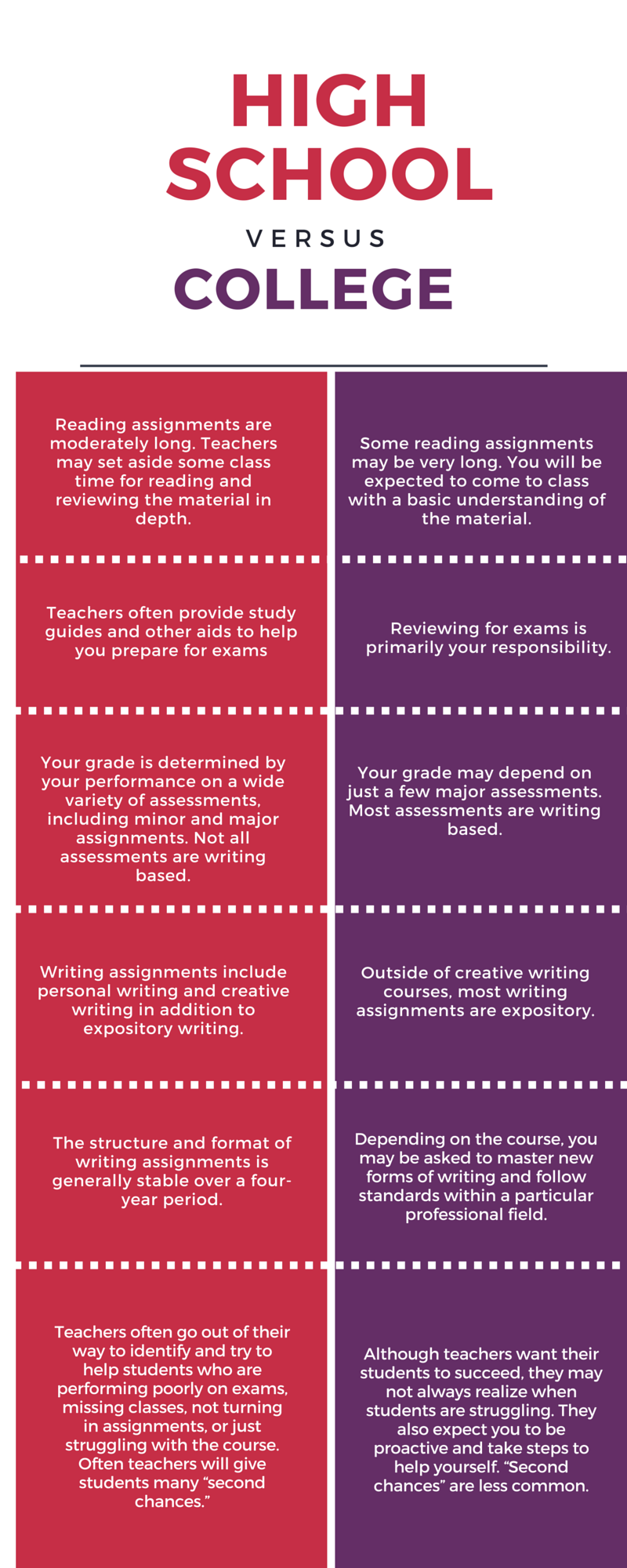

In college, academic expectations change from what you may have experienced in high school. The quantity of work you are expected to do is increased. When instructors expect you to read pages upon pages or study hours and hours for one particular course, managing your workload can be challenging. This chapter includes strategies for studying efficiently and managing your time.

The quality of the work you do also changes. It is not enough to understand course material and summarize it on an exam. You will also be expected to seriously engage with new ideas by reflecting on them, analyzing them, critiquing them, making connections, drawing conclusions, or finding new ways of thinking about a given subject. Educationally, you are moving into deeper waters. A good introductory writing course will help you swim.

Adapted from “Chapter One ” of Successful Writing, 2012, used according to creative commons 3.0 cc-by-nc-sa

Overarching Principles of Academic Writing

According to Boundless Writing, academic writing comes in many forms and can cover a wide range of subject matter; however, successful writing will demonstrate certain conventions, no matter what is being written about.

“Academic writing” is a broad term that covers a wide variety of genres across disciplines. While its features will vary, academic (or scholarly) writing generally tries to maintain a professional tone while arguing for (or against) a specific position or idea.

There are many different approaches to academic research since each discipline has its own conventions that dictate what kinds of texts and evidence are permissible. Scholarly writing typically takes an objective tone, even though it argues in favor of a specific position or stance. Academic writing can reach a broader audience through more informal venues, such as journalism and public speaking.

The Thesis Statement: Making and Supporting a Claim

Strong academic writing takes a stance on the topic it is covering—it tries to convince the reader of a certain perspective or claim. This claim is known as the “thesis statement.” The majority of an academic paper will be spent using facts and details to “prove” to the reader that the claim is true. How this is done depends on the discipline; in the sciences, a research paper will present an original experiment and data to support the claim; in a literature class, an essay will cite quotations from a text that weave into the larger argument. Regardless of discipline, the overarching goal of most academic writing is to persuade the reader to agree with the claim.

Concision

Concision is the art of using the fewest words possible to convey an idea. Some students mistakenly think that longer words and more complicated sentence structures make their writing “better” or make it sound more sophisticated. In reality, however, the longer and more complicated a sentence gets, the harder it is for a reader to interpret that sentence, and the harder it is to keep them engaged with your argument. For example, if you find yourself using a phrase like “due to the fact that,” you can simplify your wording and make your sentence more powerful by saying “because” instead. Similarly, say “now” or “currently” rather than “at this point in time.” Unnecessarily complicated wording distracts your reader from your argument; simpler sentence structures let your ideas shine through.

Objectivity

Most academic writing uses objective language. That is, rather than presenting the argument as the writer’s opinion (“I believe that …”, “I think this means …”), it tries to convince the reader that the argument is necessarily true based on the supporting facts: “this evidence reveals that …”

Breaking the Rules

There are countless examples of respected scholarly pieces that bend these principles—for instance, the “reader response” school of literary criticism abandons the objective stance altogether. However, you have to know the rules before you can break them successfully.

Think of a chef putting chili powder in hot chocolate, a delicious but unexpected bending of a rule: typically, desserts are not spicy. In order to successfully break that rule, the chef first had to understand all the flavors at work in both ingredients, and make the choice knowing that it would improve the recipe. It’s only a good idea to break these rules and principles if there is a specific, good reason to do so. Therefore, if you plan to dispense with one of these conventions, it is a good idea to make sure your instructor approves of your stylistic choice.

Building Academic Writing Skills

Academic work is an excellent way to develop strong research and writing skills. Try to use your undergraduate assignments to build your reading comprehension, critical and creative thinking, research and analytical skills. Having a specific, “real” audience will help you engage more directly with the reader and adapt to the conventions of writing in any given genre.

Seeking Help Meeting College Expectations

Depending on your education before coming to CNM, you will have varied writing experiences as compared with other students in class. Some students might have earned a GED, some might be returning to school after a decades-long break, and still other students might either be graduating high school, or be freshly graduated. If the latter is the case, you might enter college with a wealth of experience writing five-paragraph essays, book reports, and lab reports. Even the best students, however, need to make big adjustments to learn the conventions of academic writing. College-level writing obeys different rules, and learning them will help you hone your writing skills. Think of it as ascending another step up the writing ladder.

Many students feel intimidated asking for help with academic writing; after all, it’s something you’ve been doing your entire life in school. However, there’s no need to feel like it’s a sign of your lack of ability; on the contrary, many of the strongest student writers regularly seek help and support with their writing (that’s why they’re so strong). College instructors are familiar with the ups and downs of writing, and most universities have support systems in place to help students learn how to write for an academic audience. The following sections discuss common on-campus writing services, what to expect from them, and how they can help you.

Writing Mentors

Learning to write for an academic audience is challenging, but colleges like CNM offer various resources to guide students through the process. Most instructors will be happy to meet with you during office hours to discuss guidelines for writing about their particular discipline. If you have any doubts about research methods, paper structure, writing style, etc., address these uncertainties with the instructor before you hand in your paper, rather than waiting to see the critiques they write in the margins afterward. If you have questions, ask them. For example, if you’re not sure about which point of view is appropriate for a specific paper, raise your hand in class and ask your teacher. Your peers may have a similar question, but they may be too afraid to ask. Lastly, you are not bothering your instructor by showing up for office hours; they’ll be glad to see you.

Tutoring Center

Here at CNM, students have access to ACE Tutoring Services, which is available on six campuses: Advanced Technology Center, Main, Montoya, Rio Rancho, South Valley, and Westside. At these writing centers, trained tutors help students meet college-level expectations. The tutoring centers offer one-on-one meetings or group sessions for other disciplines. ACE also offers workshops on citing and learning how to develop a writing process.

Student-Led Workshops

Some courses encourage students to share their research and writing with each other, and even offer workshops where students can present their own writing and offer constructive comments to their classmates. Independent paper-writing workshops provide a space for peers with varying interests, work styles, and areas of expertise to brainstorm.

If you want to improve your writing, organizing a workshop session with your classmates is a great strategy. You can also ask your writing center to help you organize a workshop for a specific class or subject. In high school, students submit their work in multiple stages, from the thesis statement to the outline to a draft of the paper; finally, after receiving feedback on each preliminary piece, they submit a completed project. This format teaches students how to divide writing assignments into smaller tasks and schedule these tasks over an extended period of time, instead of scrambling through the entire process right before the deadline. Some college courses build this kind of writing schedule into major assignments. Even if your course does not, you can master the skill of breaking large assignments down into smaller projects instead of leaving an unmanageable amount of work until the last minute.

Academic writing can, at times, feel overwhelming. You can waste a great deal of time staring at a blank screen or a troublesome paragraph when it would be more productive to move on to drafting other parts of your paper. When you return to the problem section a few hours later (or, even better, the next day), the solution may be obvious.

Writing in drafts makes academic work more manageable. Drafting gets your ideas onto paper, which gives you more to work with than the perfectionist’s daunting blank screen. You can always return later to fix the problems that bother you.

Scheduling the Stages of Your Writing Process

Time management, not talent, has been the secret to a lot of great writing through the ages. Not even a “great” writer can produce a masterpiece the night before it’s due. Breaking a large writing task into smaller pieces will not only save your sanity, but will also result in a more thoughtful, polished final draft.

Emailing Your Instructor

Subject:

English 1110.192: Office hours on Tuesday

Dear/Hello Professor [Last name],

I have a few questions about the next essay assignment for College Writing 1110 section 192. Would it be convenient to discuss them during your office hours on Tuesday? I plan to stop and visit you during your office hours. Thank you for your help with these assignments.

Many thanks,

[First name] [Last name]

Expository Writing 101; T, Th, 10:00

Tips for Emailing Your Instructor

- Be polite: Address your professor formally, using the title “Professor” with their last name. Depending on how formal your professor seems, use the salutation “Dear,” or a more informal “Hello” or “Hi.” Don’t drop the salutation altogether, though.

- Pose a question. Clearly introduce the purpose of your email and the information you are requesting. If you are not asking a specific question, be aware that you may not receive a response to your email.

- Be concise. Instructors are busy people, and although they are typically more than happy to help you, do them the favor of getting to your point quickly. Sign off with your first and last name, the course number, and the class time. This will make it easy for your professor to identify you, and although they are typically more than happy to help you, do them the favor of getting to your point quickly.

- Do not ever ask, “When will you return our papers?” If you MUST ask, make it specific and realistic (e.g., “Will we get our papers back by the end of next week?”).

Adapted from “Chapter One ” of Successful Writing, 2012, used according to creative commons 3.0 cc-by-nc-sa