44 Chapter 28.1: The Public Argument

Part 5: Chapter 28.1

Public Argument: An Introduction

The previous chapter explained how to develop and write academic arguments. This chapter explores another type of argument, one that you likely experience each time you plug into mass media or any other technology intended to reach a mass audience. Public arguments are texts that engage public audiences and that add to a conversation involving multiple stakeholders. Unlike debates that take place in intimate conversations between two individuals, small groups, or discourse communities, public arguments are created for the purpose of sharing with others via platforms like social media, community events, popular publications, podcasts, and other venues that reach wider audiences. Unlike formal academic arguments, public arguments are created to be shared beyond a classroom of students or a group of academics who share disciplinary expertise; public arguments engage average citizens and public stakeholder groups invested in a topic or issue. Take, for example, the Black Lives Matter protests.

Date 9 July 2016, 20:09:32

In recent years, the killings of Black Americans at the hands of law enforcement have accentuated inequities within the U.S. criminal justice system, sparking movements calling for police accountability and reform. Organizations like Black Lives Matter serve to call attention to the injustices that Black Americans experience and to advocate for justice and liberation. In 2020, a series of events unfolded that incited national outcry in support of Black lives, including the death of George Floyd, whose confrontation with police officers was captured on camera and shared widely on social media and in news outlets. As a consequence of this and other similar cases, protests across the U.S. were held to demand justice and to argue for change.

In light of these events, which for many Americans highlight the precarity of Black lived experience, average citizens were taking action: They were calling and writing to state and local officials, signing petitions, attending protests, sharing information and resources on social media, and donating to causes. Yet there were also Americans who were counter-protesting: They challenged the idea of systemic racism, asserted that “all lives matter,” and defended the actions of police officers in these controversial moments. As might be expected, the tensions that arose within this time period created numerous opportunities for debate, discussion, and argument. And because many of these exchanges took place within public contexts, they resulted in the creation of various forms of public argument.

The stakeholders in this issue are many and diverse, including Black Americans, non-Black allies, law enforcement, government officials and representatives, national organizations like the NAACP, and media outlets—just to name a few. Each of these groups plays an important role in the conversation taking place and hold unique perspectives that illustrate the complexity of the issue. Stakeholders most certainly reflect differing attitudes, values, beliefs, and motives that inform their participation in the conversation. Crafting a public argument necessitates that you consider the stakeholder audiences invested in an issue, identify their various positions and concerns, and then choose a stakeholder group to serve as the audience for your message. As this example illustrates, unlike traditional academic arguments, your public argument will be directed toward people outside of your college writing class, where it will be engaged by public audiences and where it can add meaningfully to an ongoing discussion.

How to Plan Your Public Argument

After you’ve substantially researched the issue or topic surrounding your public argument, you are ready to begin planning and brainstorming for your text. This section is meant to help you consider what to keep in mind as you move into this initial stage of the writing process. Keeping in mind these five questions as you plan will help ensure you create a rhetorically effective public argument:

- What stakeholder group, or audience, would you like to reach with your public argument, and what do you know about their concerns, attitudes, and beliefs toward the topic?

- What kinds of texts are your audience most likely to engage? What genre (type of text) will you create and why is it a sound choice for your stakeholder group?

- How will you disseminate the public argument to your chosen audience? What medium (mode of delivery) will you employ and why is it a sound choice for your stakeholder group?

- What is the message of your public argument and how can you use the research you’ve collected to support or illustrate this message?

- What are the key supporting points that you need to include in order to create a persuasive public argument for your chosen audience?

Analyzing Your Stakeholder Audience

As you read in Chapter 5 of this textbook, considering your audience is crucial to ensuring you create an effective piece of writing. In addition to the advice included in that chapter, you may need to conduct research on your stakeholder group to better understand their needs, concerns, attitudes, and beliefs in relation to the topic you’ve chosen. In other words, you will need to do more than just identify your audience and consider what they already know, or need to know, about your topic; you will also need to analyze who they are, what information they require, and how to reach them.

When you conduct an analysis of your audience, you are thinking closely about the needs of your chosen stakeholder group. For example, you might consider:

- What is the demographic background of your audience (their age, gender, race, nationality, sexual orientation, etc.) and how might these factors affect their reception of your public argument?

- What is your audience’s education level, and how might that affect the information you include in your public argument?

- What are the audience’s existing concerns, attitudes, and beliefs? How might you appeal to shared concerns, attitudes, or beliefs in crafting your argument?

- What does your audience know about the topic already? What do they need to know in order to accept your message?

- What types of evidence are most likely to persuade the audience you’ve chosen? Will they be more receptive of logos-based arguments, or of pathos-based ones? To visual or textual evidence? How will you demonstrate your own credibility and trustworthiness in crafting your public argument?

These are just some of the questions to think about as you delve into your audience analysis. For continued practice in analyzing your audience, consider completing this Audience Planner activity, developed by David McMurrey and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Selecting Your Genre and Medium

As you plan your public argument, it is important that you consider the genres, or types of texts, that your audience is likely to connect with. You will also need to carefully consider the medium of your public argument, which speaks to how you will share the information with this audience. For example, say you want to create a series of advertisements that will persuade young voters in your state to exercise their right to vote, and you want to deliver these advertisements via social media. The genre of your public argument would be an advertisement, but the medium, or mode of delivery, would be the social media platform(s) where you share these ads. The genre and medium are an appropriate choice for your target audience of young voters, since findings from the Pew Research Center indicate that over 80% of social media users are between the ages of 18-29 (“Social Media Fact Sheet”). In this case, you have demonstrated attention to your rhetorical situation by thinking closely about your target audience and their habits of social media use, as well as the types of texts they are likely to encounter there.

Some instructors may want you to create a multimodal public argument, meaning that it communicates using a variety of modes, including textual, visual, aural, tactile, electronic, performative, and so forth. For instance, let’s say that in the previous example of creating ads for young voters, the ads include both images and text-based evidence; since the ads communicate in multiple modes (visually and textually), they are multimodal. As you consider the modes of communication for your public argument, make sure to check with your instructor regarding the assignment requirements and expectations to ensure that you create a successful project.

For many students, selecting a genre and medium for your public argument will present challenges because unlike traditional assignments, public arguments give you many options and allow you to exercise creative choice. Sometimes having limitless possibilities makes it difficult to narrow and choose what kind of text to create! If you are struggling to think of examples of genres and media, use the following list as a starting point:

Examples of Public Argument Genres:

| · Advertisements

· Op-Eds · News articles · Newsletters · Brochures · Presentations · Art pieces · Photo essays · Protest posters · Social media posts · E-mails · Blogs · Podcasts · Letters |

· FAQ sheets

· Videos · Short films · Websites · Quick reference guides · Creative writing (such as poetry or fiction) · Musical compositions · Infographics · Manifestos · Performances · Speeches · Petitions Signs and billboards |

While this is not an exhaustive list, it can provide you with a starting point for brainstorming the type of text you might create. It may be important for you to research your chosen genre to ensure you follow genre conventions. Doing so may be as simple as reviewing several examples of the genre in order to understand some of the common moves noticeable within the genre.

Just as important is for you to consider how you will deliver this message to your audience, or the medium of your text. For example, will you create a print-based document that will be delivered in hard copy? Texts such as print ads, newsletters, brochures, newspaper or magazine articles, posters, or infographics are often generated for print. Alternatively, you might create a text that will be delivered digitally, such as a website, social media posts, e-mail, infographic, blog, video, or online FAQ sheet. Regardless of the type of public argument you choose to create, it will be important for you to consider how the information will be shared with your audience and whether this medium makes sense for the audience’s needs and concerns.

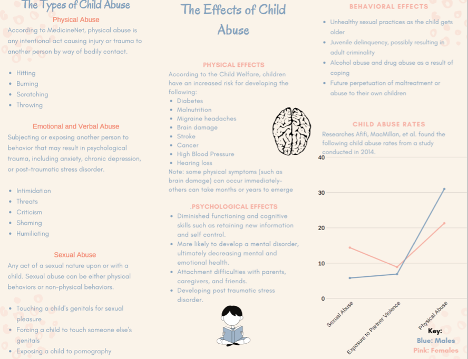

Consider the following tri-fold brochure created by English 1120 student Amena Jameson. As a nursing student, Amena wanted to research and write about the effects of abuse in children, a topic relevant to her future career. Specifically, she wanted to reach parents who would be caring for their child(ren) and to educate them about the negative consequences of abuse. Considering this audience and purpose, Amena decided to create a brochure (a print-based medium) that could be displayed at local pediatricians’ offices.

Review her sample brochure and consider its rhetorical effectiveness. Does a brochure seem like an appropriate choice for the writer’s situation? Why or why not? How effectively has the writer responded to her audience’s needs and concerns in creating the brochure? In what ways does the brochure reflect multimodal composition? What do you notice about how the writer presents information to her audience of parents? What information seems most relevant to her audience and purpose and why?

Framing Your Message and Choosing Supporting Points

By the time you get ready to create your public argument, you should have completed in-depth research about your chosen topic (and hopefully explored multiple stakeholder perspectives), and you should have an understanding of the conversation that is taking place. As you read and learn about your topic, you will begin to develop your own stance based on the information you encounter that resonates with you most—that you find most persuasive or compelling. As you begin to gather evidence in support of your position, you will need to begin narrowing down the message you want to share with your chosen audience based on the information you’ve gathered. It’s unlikely that you’ll be able to include all the research you’ve read, so it will be important for you to be rhetorically selective—that is, you will need to consider your audience, your purpose, and your message, and you will need to choose information that most effectively supports your writing situation.

Keep in mind that public arguments do not frame their message in the same way that a thesis in a formal academic argument would. Whereas academic arguments are often complex and rely on nuanced language to convey their positions, public arguments are often stated more directly and accessibly. Oftentimes, public arguments use concise, carefully chosen phrases to convey their stance. Consider slogans like “Black Lives Matter,” “Planet Over Profits,” or “Never Again.” Each of these phrases represents a stance, a movement, a stakeholder group in a larger conversation. Each conveys its message both simply and succinctly. If these messages were written for a formal academic argument, they would take on an entirely different tone.

Academic Thesis: Black Americans face numerous injustices as a result of their race, including experiencing higher rates of police brutality than other racial groups; therefore, criminal justice reform is needed to ensure the safety and security of Black Americans’ lives.

Public Argument Message: Black Lives Matter.

As you consider the message of your public argument, brainstorm ways to articulate this message clearly and in a way that will be readily intelligible to your audience. Your message should be prominently displayed or stated within your public argument so that it frames the text and supports your purpose.

Take, for example, Jenny Castro’s infographic on music piracy. After presenting readers with evidence about the effects of music piracy, informed by the research she conducted, Castro states the message of her public argument. The message is clearly displayed at the bottom of the text, emphasized in all caps: Don’t Illegally Download Music. Notice how Castro organizes content cohesively within the infographic, using bolded headings to underscore each supporting point. First, she provides evidence to illustrate the problem, noting that the U.S. surpasses other countries in illegally downloading music; then, she details ways that piracy affects various stakeholders in the music industry, resulting in financial losses to record labels and musicians and to decreases in jobs within the industry as a whole. She provides her audience with solutions in the form of free streaming services like Spotify and Pandora, and appeals to her audience’s sense of what is ethically right when she reminds them that piracy is indeed a form of theft. By the time her readers reach the conclusion of her infographic, where her message is clearly stated, they have been provided with multiple reasons and evidence as to why they should avoid illegally downloading music.

As you develop your message and develop supporting claims and evidence for your public argument, you might consider the following questions:

- What message do you want to share with your audience, and how can you articulate this message clearly and concisely within your public argument?

- What supporting points will most effectively promote your message? What supporting points are most likely to resonate with your target audience?

- What supporting evidence will you include to back up each supporting point? What evidence is most likely to be accepted by your audience?

- How will your organize content to ensure you create a cohesive public argument?

Engaging Sample Public Arguments

This section includes additional examples of public arguments that were created by English 1120 students at CNM. As you review these examples, consider the following questions:

- What stakeholder group, or audience, does this public argument speak to what clues in the text signal the audience?

- What genre (type of text) and medium (mode of delivery) are represented, and to what extent are these sound choices for the stakeholder group?

- What is the message of the public argument and how does the writer use research to support or illustrate this message?

- What are the key supporting points that are included in the public argument and how effective are these points in creating a persuasive public argument for the target audience?

Example #1:

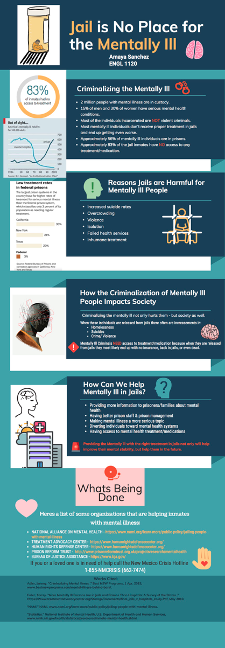

Example #2: Infographic by Amaya Sanchez

Creating a public argument for your writing class presents you with unique opportunities for using your writing to share information with audiences about issues that matter to you. As you plan your public argument, consider the audience you want to reach, the texts and platforms they are most likely to connect with, the message you want to share, and the supporting points and evidence that will help you create a persuasive public text. With these strategies in mind, you will be able to use your writing to reach public audiences—beyond your college classroom—as you enter a conversation of stakeholders invested in an issue. Public writing may even inspire change, move people to action, or otherwise make a difference in the world.

Image Credits:

https://ccsearch.creativecommons.org/photos/df3bdd51-4440-4ff4-9710-677024ea0ac0

Other CC Credits:

https://www.prismnet.com/~hcexres/itcm/planners/aud_plan.html

This chapter was written by Dr. Marissa Juarez, published by Central New Mexico Community College 2020, and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0