47 Chapter 30.1: Exploratory Essays and Informative Research Papers

Part 6: Chapter 30.1

In English 1110, if you have not completed this process, you may want to begin by utilizing your first paper, the personal narrative, as a springboard for learning about research in college writing. What experiences have helped formulate your ideas or position on a topic? How can your experiences help you develop your research questions?

To begin, let’s learn about the differences between an Exploratory Essay and an Informative Research Report:

The Exploratory Essay is often introduced as a research project that presents a set of different questions about a topic and attempts to answers these questions through informal sources such as non-specific Google searches and strategic Google searches, or article databases including newspapers and magazines. This type of essay is written from the perspective of someone who seeks general answers and encourages students to begin learning basic citation formatting and practice honing keyword lists to navigate online search engines while applying evaluation tools to assess the reliability of these sources.

The Informative Research Report is a report that relays the results of a central research question in an organized manner through more formal sources. These resources could include Google Scholar, library catalogs and academic article databases, websites of relevant agencies, and Google searches using (site: *.gov or site: *.org). A report is written from the perspective of someone who is seeking to find specific and in-depth information about a certain aspect of a topic.

The Research Process

According to Successful College Composition, no matter what field of study you pursue, you will most likely be asked to compose a research project in your college degree program and to apply the skills of research and writing in your career. This process is similar to the process professionals use when they begin a research project. Learning this research process allows students to complete research to answer specific questions, to share their findings with others, to increase their understanding of challenging topics, and to strengthen their analytical skills. Practicing these skills will help prepare students for future academic tasks and professional writing tasks.

Having to complete a research project may feel intimidating at first. After all, researching and composing requires time, effort, and organization. However, its challenges have rewards. The research process allows you to gain expertise on a topic of your choice.

The writing process helps you to remember what you learned, to understand it on a deeper level, and to develop expertise. Thus, writing a research paper can be a great opportunity to explore a question and topic that particularly interests you and to grow as a person.

Exploratory Essays

The exploratory essay serves as an early and informal entry into research where students can continue to explore multiple issues related to their narrative assignment and ask, “what questions about myself or my community emerge from this narrative?”

Many college writing assignments call for you to establish a position and defend that position with an effective argument. However, some assignments are not argumentative but exploratory in nature. Exploratory essays ask questions and gather information that may answer these questions. However, the main point of the exploratory essay is not to find definite answers. The main point is to conduct inquiry into a topic, gather information, and share that information with readers.

Using your narrative as springboard, students will explore multiple issues related to their personal narrative assignment. For example, a student who writes a narrative about generational language loss may choose to research language policies in the U.S., or, a student who writes a community narrative about being a bicyclist in New Mexico might research cyclists’ rights to the road and national vs. statewide safety statistics. Your goal is to ask questions about your topic, find sources to help you answer those questions, and determine if the sources you found are helpful. For more information, review this Exploratory Essay PowerPoint.

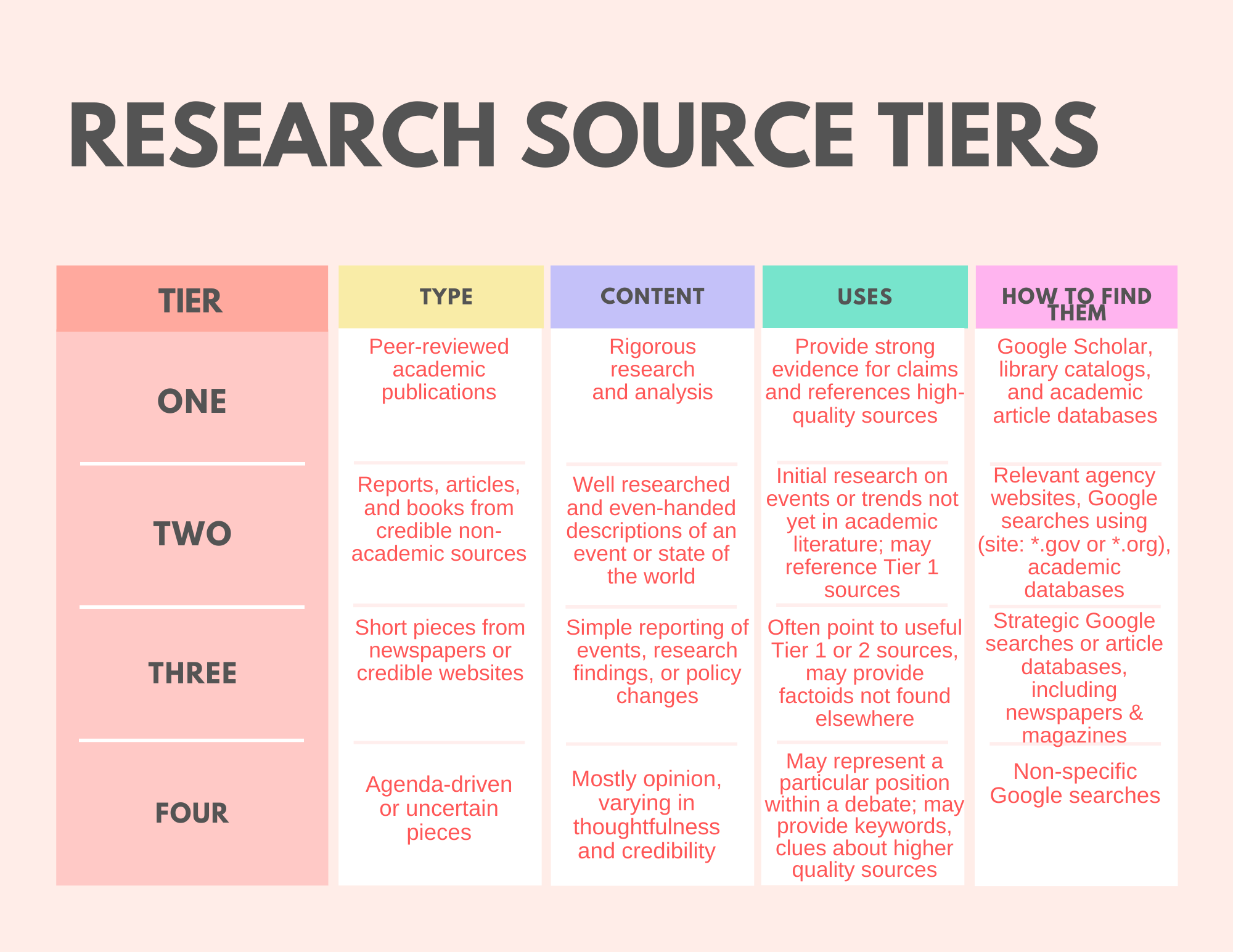

According to Writing in College, sources can be categorized into four tiers according to type, content, uses, and research methods.

Students begin learning basic citation formatting during this process. As you consider your narrative, you will learn to utilize that information to begin honing keyword lists to navigate online search engines while applying evaluation tools to assess the reliability of these sources. The Exploratory Essay draws primarily from resources found in tiers 3 and 4:

Tier 3. Short pieces from periodicals or credible websites

A step below the well-developed reports and feature articles that make up Tier 2 are the short tidbits that one finds in newspapers and magazines or credible websites. How short is a short news article? Usually, they’re just a couple paragraphs or less, and they’re often reporting on just one concept: an event, an interesting research finding, or a policy change. They don’t take extensive research and analysis to write, and many just summarize a press release written and distributed by an organization or business. They may describe issues like corporate mergers, newly discovered diet-health links, or important school-funding legislation.

You may want to cite Tier 3 sources in your paper if they provide an important factoid or two that isn’t provided by a higher-tier piece, but if the Tier 3 article describes a particular study or academic expert, your best bet is to find the journal article or book it is reporting on and use that Tier 1 source instead. If the article mentions which journal the study was published in, you can access that journal through your library website. What counts as a credible website in this tier? You may need some guidance from instructors or librarians, but you can learn a lot by examining the person or organization providing the information (look for an “About” link). For example, if the organization is clearly agenda-driven or not up-front about its aims and/or funding sources, then it is not a source you want to cite as a neutral authority. Also look for signs of expertise. A quote about a medical research finding written by someone with a science background carries more weight than the same topic written by a policy analyst. These sources are sometimes uncertain, which is all the more reason to follow the trail to a Tier 1 or Tier 2 source whenever possible.

Tier 4. Agenda-driven or pieces from unknown sources

Tier 4 sources can be helpful in identifying interesting topics, positions within a debate, keywords to search on, and, sometimes, higher-tier sources on the topic. They often play a critically important role in the early part of the research process, but they generally aren’t (and shouldn’t be) cited in the final paper. Entering keywords into Google and reviewing those results is a fine way to begin your research, but don’t stop there. Start a list of the people, organizations, sources, and keywords that seem most relevant to your topic. For example, suppose you’ve been assigned a research paper about the impact of linen production and trade on the ancient world. A quick Google search reveals that (1) linen comes from the flax plant, (2) the scientific name for flax is Linum usitatissimum, (3) Egypt dominated linen production at the height of its empire, and (4) Alex J. Warden published a book about ancient linen trade in 1867. Similarly, you found some useful search terms to try instead of “ancient world” (antiquity, Egyptian empire, ancient Egypt, ancient Mediterranean) and some generalizations for linen (fabric, textiles, or weaving). Now you have a starting point to tap into the library catalog and academic article databases.

Suggestions for Organizing Exploratory Essays

Introduction

Your introduction should be the platform for your essay. Here, you will introduce important context – you can begin by providing general background information and set up a “map” of what the paper will discuss. There are several goals for the introduction. First, state the importance of this topic – the introduction should also compel the audience to read further and create interest in the topic. Second, state the questions or topic of exploration that initiated this research – this can be one or several sentences or questions that states what the author is interested in finding out, why, and how they intend to complete the research process Third, provide a brief overview of the types of sources you researched during your inquiry to establish your credibility.

Body Paragraphs

As you shift into writing your essay, work to create body paragraphs that discuss the inquiry process you followed to research your topic. These paragraphs should include the following:

- A question you have about your topic. You should begin each body paragraph with a different question.

- Introduction of source (title, author, type of media, publisher, publication date, etc.) and why you chose to use it in your exploration.

- Important information you found in the source regarding your topic; include a direct quote using P.I.E. (See ch. 9.1)

- Explain why the information is important and dependable in relation to the topic.

- Some personal introspection on how the source helped you, encouraged you to think differently about the problem, or even fell short of your expectations and led you in a new direction in your research, which forms a transition into your next source.

Conclusion

The conclusion should provide a general overview of what has been discussed. Here, bring up questions regarding the topic you explored and if the sources you found were helpful in answering these questions. Consider stating what other questions surfaced through your research and focus on; you will use one or a few of these questions that will drive your inquiries for the Informative Research Report.

Informative Research Reports

The purpose of an informative essay, sometimes called an expository essay, is to educate others on a certain topic. Typically, these essays aim to answer the 5 Ws and H questions: who, what, where, when, why, and how. For this essay, you will focus on one or two driving questions about your topic , which will drive your research and help you reach a conclusion. The question can be one that emerged from your Exploratory Essay or it can be a brand-new question about your topic that you are interested in researching.

The point of an informative essay is not to convince others to take a certain action or stance; that role is expressly reserved for persuasive essays. Instead, the main objective is to highlight specific information about your topic. In this project, you may be asking “after researching general aspects about my narrative, what do I want others to understand about it?” Of course, if your informative essay is interesting enough, it may move readers to learn more about the subject, but they’ll have to come to that on their own, thanks to the wealth of interesting information you present.

Now that you have spent time considering different aspects of your topic in your exploratory essay, you will continue your research through our CNM library resources to help inform a larger audience about your topic. The final unit builds upon students’ existing research skills and introduces them to library resources and other higher-level tiered resources. Students should have a clearer idea of their research topic and can begin exploring common challenges to finding relevant sources and managing them (recording citation details, quoting, paraphrasing, citing). For more information, review Structuring an Informational Report.

The Informative Research Report draws primarily from resources found in tiers 1 and 2 according to the research table in Writing in College:

Tier 1: Peer-reviewed academic publications

These are sources from the mainstream academic literature: books and scholarly articles. Academic books generally fall into three categories: (1) textbooks written with students in mind, (2) monographs which give an extended report on a large research project, and (3) edited volumes in which each chapter is authored by different people. Scholarly articles appear in academic journals, which are published multiple times a year in order to share the latest research findings with scholars in the field. They’re usually sponsored by some academic society. To get published, these articles and books had to earn favorable anonymous evaluations by qualified scholars.

Tier 2: Reports, articles and books from credible non-academic sources

Some events and trends are too recent to appear in Tier 1 sources. Also, Tier 1 sources tend to be highly specific, and sometimes you need a more general perspective on a topic. Thus, Tier 2 sources can provide quality information that is more accessible to non-academics. There are three main categories. First, official reports from government agencies or major international institutions like the World Bank or the United Nations; these institutions generally have research departments staffed with qualified experts who seek to provide rigorous, even-handed information to decision-makers. Second, feature articles from major newspapers and magazines like the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, London Times, or The Economist are based on original reporting by experienced journalists (not press releases) and are typically 1500+ words in length. Third, there are some great books from non-academic presses that cite their sources; they’re often written by journalists. All three of these sources are generally well researched descriptions of an event or state of the world, undertaken by credentialed experts who generally seek to be even-handed.

Suggestions for Organizing Informative Research Reports

Introduction

The initial stage is an introduction, which should start with the sound hook sentence to engage the reader in what a writer plans to share. One example is: “A community is generally defined by people in a group who live together in a particular area, or a group of people who are considered a unit because of their shared interests or background.” Then, introduce the topic with its background in a couple of sentences. The writer will then end the paragraph with a powerful thesis statement, which points to the necessity of topic research. The writer’s goal is to do everything possible to lure the audience’s interest in the initial paragraph.

- Define the topic.

- Provide short background information.

- State who your intended audience is.

- State what your driving research question is.

- Create a thesis statement by identifying the scope of the informative essay (the main point you want your audience to understand about your topic).

Body Paragraphs

The main purpose of the body paragraphs is to inform the target audience about the background/significance of your topic or the answers to the 5 Ws and H driving questions that you focused your research on. Share some interesting facts, go into the possibly unknown details, or reflect common knowledge in a new light to make readers intrigued. Body paragraphs should discuss the inquiry process you followed to research your topic. These paragraphs should include the following:

- Begin with a topic sentence. Using one of the 5 Ws or H questions here will remind you and your readers what you will focus on in this paragraph.

- Introduce your sources in a sentence or two to summarize what the information revealed about your topic.

- Include a direct quote using P.I.E. and reflect on what the source illuminated about your question.

Conclusion

The conclusion is your opportunity to summarize the essay and hopefully spur the reader to want to learn more about the topic. Be sure to clearly reiterate the thesis statement. In your introduction, you may have laid out what would be covered in the essay. Offer a sentence or two reiterating what was learned about those topic areas. Finally, work to avoid adding any new information and questions in this final section of your writing.

- Reword the thesis sentence(s).

- Reiterate the key points of your research.

- Offer some forecasts for the future (example: “Hopefully now with a clearer understanding about free soloing and the rock-climbing community, others might understand the draw to such a seemingly risky sport…”).

This chapter is a synthesis of three texts:

Adapted from “Chapter 4.1” of Successful College Composition, 2016, used according to Creative Commons CC BY-NC-SA 3.0, and adapted from “Secondary Sources in Their Natural Habitat” of Writing in College, 2016, used according to Creative Commons CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Sections are also written by Dr. Danizete Martinez, published by Central New Mexico Community College, 2020, and licensed according to Creative Commons CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.