5

Learning Objectives

- Identify pre-gestational conditions placing the pregnancy at risk and the resulting complications.

-

Describe pregnancy-related complications that place a pregnancy at-risk.

-

Identify indications for antenatal procedures utilized to assess fetal well-being.

Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy

Gestational hypertension is a condition in which vasospasm occurs in both small and large arteries during pregnancy, causing an increase in the blood pressure. The result leads to hypertensive episodes and disorders of pregnancy.

Gestational Hypertension:

Hypertension (SBP > 140 or DBP >90) detected for the first time after mid-pregnancy (20 weeks) without proteinuria. Pressures should be recorded on two occasions at least 4 hours apart. Approximately 1/3 of these women subsequently develop preeclampsia. Diagnosis not confirmed until blood pressure returns to normal by the 12th week postpartum (If it does not return to normal, chronic hypertension would be diagnosed)

Preeclampsia:

A systemic disease characterized by hypertension (SBP > 140 or DBP >90 on 2 readings 4 hours apart; OR 160/110 once), proteinuria/creatinine ratio of 0.3 or more; or 2+ dipstick after the 20th week of gestation. In the absence of proteinuria, the diagnosis can still be made if any of the severe features are present. The cause is unknown and every organ system is affected. The definitive cure is the delivery of the fetus and placenta.

The pathophysiology of preeclampsia is derived from the abnormal development of the placental vasculature early in pregnancy which leads to placental hypoperfusion, hypoxemia, and ischemia. This process releases toxic mediators that lead to a systemic inflammatory response and endothelial damage. It is generally agreed that the clinical manifestations in preeclampsia are related to widespread endothelial dysfunction. Therefore, a loss of endothelial control of vascular tone leads to hypertension, the increased vascular permeability leads to edema and proteinuria, and abnormal endothelial expression of procoagulants leads to increased coagulopathy. A multitude of risk factors exists for developing preeclampsia including the following: nulliparity, preeclampsia with a previous pregnancy, advanced maternal age, chronic hypertension, chronic renal disease, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome or thrombophilia, vascular or connective tissue disease (SLE), pregestational diabetes or diabetes, multiple gestations, obesity, assisted reproductive technology (ART), and obstructive sleep apnea.

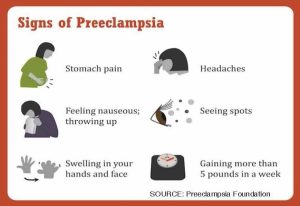

Signs and symptoms of preeclampsia include persistent hypertension, central nervous system (CNS) symptoms (headache, visual disturbances, hyperreflexia & clonus, seizure (1/400 of mild preeclamptic clients; 2% of severe, and stroke), liver involvement that is manifested by right upper quadrant pain, nausea and vomiting. Clients may state they just don’t feel well, and may also present with dyspnea due to pulmonary edema. It is important for the nurse when assesses all patients to always ask the following three questions:

- Do you have any headaches?

- Are you having any visual disturbances?

- Are you having any right upper quadrant or epigastric pain?

Preeclampsia with severe features: BP ≥ 160/110; platelets < 100,000; elevated liver enzymes (twice normal) or RUQ pain; serum creatinine concentration >1.1 mg/dl; pulmonary edema, cerebral or visual symptoms.

Eclampsia:

The onset of seizures (tonic-clonic, focal, or multifocal) in a woman with preeclampsia cannot be explained by another cause. Seizures may appear before, during, or after labor

Chronic Hypertension:

Hypertension SBP > 140 or DBP >90 before conception or before 20th-week gestation or hypertension diagnosed after 20 weeks gestation and persistent after 12 weeks postpartum. The pregnant client that presents with chronic hypertension is at increased risk of developing preeclampsia. A baseline 24-hour urine protein should be collected to assess adequately. Chronic hypertension is typically managed with Methyldopa or Labetalol

Chronic Hypertension with Superimposed Preeclampsia:

Chronic hypertension superimposed preeclampsia presents with the pregnant client with new-onset proteinuria > 300 mg/24 hours in hypertensive women without proteinuria before 20 weeks gestation. A sudden increase in proteinuria or hypertension in women with hypertension and proteinuria before 20 weeks gestation

HELLP Syndrome:

Occurs as a complication of severe preeclampsia; Associated with high mortality, morbidity; delivery needs to occur regardless of gestational age; Symptoms: flu-like, nausea, vomiting, epigastric pain. It is defined as the following:

H = Hemolysis: RBC’s destroyed as they travel through constricted vessels

EL = Elevated Liver Enzymes: Endothelial damage and fibrin deposits lead to subsequent damage to the liver

LP = Low Platelets: Due to platelet aggregation at the site of damaged vascular endothelium causing platelet consumption and thrombocytopenia

Treatment for Preeclampsia

The definitive treatment for preeclampsia is delivery of the newborn. Delivery is recommended for any patient at least 37 weeks gestation and may also be indicated at less than 37 weeks in the presence of severe disease. Anticonvulsant therapy (magnesium sulfate) may be started along with antihypertensive therapy. Antihypertensive therapy is usually initiated when SBP is ≥160 mmHg and/or DBP is ≥105 to 110 consideration must be made on the effect on the fetus if blood pressure dropped too low. Target goal: SBP 140-150; DBP 90-100. The expectant management includes if <37 weeks and no severe features include: Restricted activity (although there is no evidence that supports that complete bed rest improves outcome), daily fetal movement counts, nonstress test and/or biophysical profile, ultrasound to evaluate growth and AFI, umbilical artery flow study (if growth is a concern), repeat laboratory evaluation once or twice weekly, platelet count, serum creatinine, and liver enzymes, antenatal corticosteroids to promote fetal lung maturity (may be used for any pregnancy between 23 and 36 6/7 weeks).

Antihypertensive drugs are used to help lower blood pressure (BP) as needed. Management of care is necessary to minimize a rapid decrease in the BP due to the decrease in uteroplacental perfusion that will lead to the decrease in oxygen to the fetus.

Magnesium sulfate is used to prevent seizures and may have a slight effect in lowering the BP due to the impact on the smooth muscle of the heart. However, the main purpose is for the prevention of seizures. It is administered via continuous IV and typically has a loading dose of 4-6 grams (6gm typically used with clients with BMI > 35) diluted in 100 ml over 15-20 minutes. During this time it is important for the nurse to assess the patient and monitor vital signs prior to administration and every 5-15 minutes during the loading dose and every 30-60 minutes after. The nurse in addition to monitoring vital signs will need to assess respiratory status including lung sounds, deep tendon reflexes, and urine output every hour. The nurse will maintain strict input and output measurements via foley, along with continuous fetal monitoring and placing the client on seizure precautions. Maintenance for magnesium sulfate is typically 2 grams/hour via IV infusion and continues 24 hours after delivery. Serum lab levels are drawn every 4-6 hours to ensure a therapeutic range of 4-7 mEq/L is maintained, >12 mEq/L can cause respiratory and cardiac arrest. The nurse will continuously monitor for signs of magnesium sulfate toxicity. Decreased respiratory rate, decreased reflexes, oliguria <30 ml/hour, confusion, and change in the level of consciousness may all be signs of toxicity. Calcium gluconate can be administered via slow IV push over 3 minutes. Maternal side effects of magnesium sulfate include nausea, flushing, diaphoresis, blurred vision, lethargy, and uterine atony. Fetal or neonatal side effects include decreased heart rate variability, respiratory distress, hypotonia, and a decreased suck reflex. There are benefits to the newborn with neuroprotection in preterm newborns that can protect from cerebral palsy.

The pregnant client presenting with Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy is at risk of cerebral edema, hemorrhagic stroke, disseminated intravascular hemorrhage, pulmonary edema, congestive heart failure, hepatic failure, renal failure, and abruptio placenta (CMQCC, 2022). The pregnant client is also at risk for Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC) which occurs when there is such extreme bleeding and so many platelets and fibrin from the general circulation rush to the site that there is not enough left in the rest of the body. This results in a paradox: At one point in the circulatory system, the person has increased coagulation, but throughout the rest of the system, a bleeding defect exists. DIC is an emergency because it can result in extreme blood loss. Goals for care should reflect the presence of an emergency. Many times with DIC, the treatment would include a hysterectomy in order to help control the bleeding. Management of the women that develop DIC is the rapid replacement of blood loss and is considered intensive care. Pregnant clients with hypertensive disorders are also at risk for lifelong complications that can impede future pregnancies. Fetal risks associated with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy include prematurity, intrauterine growth restriction, low birth weight, fetal intolerance to labor due to decreased placental perfusion, and stillbirth.

Cervical Insufficiency

Formally known as incompetent cervix. It occurs in about 1% of women. The dilatation usually occurs painlessly, so often the first symptom is show (a pink-stained vaginal discharge) or increased pelvic pressure, which then is followed by rupture of the membranes and discharge of the amniotic fluid. In early preterm labor, at about 20 weeks gestation, the cervix begins to dilate and the result is a loss of pregnancy. This may be due to a mechanical defect in the cervix that results in painless cervical dilatation and ballooning of the membranes into the vagina followed by the expulsion of a premature infant during the second-trimester Results in multiple second-trimester abortions without contractions.

Causes:

- Previous cervical trauma from LEEP or D&Cs

- DES exposure in utero

- Bicornuate uterus

Diagnosis/Treatment:

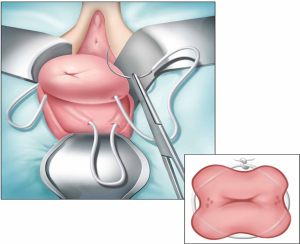

- Cerclage placed between 12 and 14 weeks gestation; will be removed at 37 weeks gestation

- Ultrasound assessments of cervical length and funneling

- Bedrest

- Avoid sexual activity

- Progesterone

- Antibiotics or tocolytics as indicated

Bleeding in Pregnancy

Early Pregnancy Bleeding

Early pregnancy bleeding is classified as bleeding that occurs before 20 weeks. Vaginal bleeding during pregnancy is always a deviation from the normal, is always potentially serious, may occur at any point during pregnancy, and is always frightening. It must always be carefully investigated because it can impair both the outcome of the pregnancy and the woman’s health or life. Spontaneous abortion is a spontaneous pregnancy termination prior to 20 weeks gestation or with a fetus weighing less than 500 grams (also called miscarriage) it can occur before pregnancy even recognized and seen as a heavy menstrual period. In recognized pregnancies, the incidence is about 12%. Causes for spontaneous abortion include chromosomal abnormalities, abnormalities of the reproductive tract or placenta, maternal diseases, and infections. In most cases of spontaneous abortion or miscarriage, there will be bleeding, cramping, and/or backache; there may or not be dilation of the cervical os

- Threatened Abortion: vaginal bleeding, cramping, backache, cervix closed

- Inevitable Abortion: vaginal bleeding, cramping, dilatation of the internal cervical os

- Incomplete Abortion: products of conception retained (usually the placenta), cervical os open (will need D&C–Post D&C: teach to watch for heavy bleeding, fever, chills, foul-smelling discharge, abdominal tenderness)

- Complete Abortion: all the products of conception are expelled, cervical os may be closed

- Missed Abortion: the fetus dies in utero but is not expelled

- Recurrent (or Habitual) Abortion: consecutive occurrence in three or more pregnancies

- Septic Abortion: the presence of infection in association with the spontaneous abortion

Women who are Rh-negative will need Rh immune globulin to prevent sensitization. Patient and family may experience feelings of grief, sadness, ambivalence, or guilt—providing emotional support are encouraged as long as the patient and family are receptive.

Ectopic Pregnancy

Implantation of a fertilized ovum in a site other than the endometrial lining of the uterus, most commonly in the ampulla of the fallopian tube, but also can implant in the ovary or elsewhere. Implanted cells grow into the adjacent tissue. Caused by a slowed or prevented passage of a fertilized ovum through the fallopian tube due to tubal damage from infection, prior surgery, or presence of an IUD. Risk factors also include smoking and advanced maternal age. Symptoms of pregnancy may initially be present: E.g. amenorrhea, elevated hCG levels, nausea, and breast tenderness. Classic symptoms of an ectopic pregnancy include unilateral lower quadrant pain, delayed menses, abnormal vaginal bleeding. The ectopic pregnancy can cause internal hemorrhage if the fallopian tube ruptures, fainting, and dizziness may occur, if the internal hemorrhage is severe, shock may ensue.

This patient would present in ER or physician’s office:

- Assess appearance and amount of vaginal bleeding

- Assess BP, pulse, and respiration for signs of shock

- Prepare the patient for emergency surgery if the ectopic has ruptured

- Establish IV therapy and blood transfusion capability

- Assess emotional needs of the couple and family and provide support

- Some ectopics may be treated with methotrexate* and close monitoring (serial hCG levels)

- Give Rh immune globulin to Rh-negative woman

*Methotrexate: Class: Folic acid antagonist. Action: inhibits DNA synthesis, repair, and cellular replication—interferes with the proliferation of trophoblastic cells. Extremely teratogenic. Dosing for ectopic pregnancy: 1 mg/kg IM for 1-3 doses.

Gestational Trophoblastic Disease

An abnormal proliferation of trophoblast cells, fertilization, or division defect. Also called Hydatidiform mole (molar pregnancy) occurs in 1 in 1500 pregnancies in the U.S. The trophoblast is the outermost layer of embryonic cells that give rise to the chorion (and the placenta). This disease includes partial or complete hydatidiform mole, invasive mole, and choriocarcinoma

Complete mole:

- Develops from an anuclear ovum (“empty egg”)

- Fertilized by a haploid sperm (23X) and duplicates to become 46XX of total paternal origin

- No embryonic or fetal tissue are found

Partial mole:

- Normal ovum fertilized by two sperm or one sperm that did not undergo meiosis and therefore had 46 chromosomes

- Results in a triploid karyotype (69 chromosomes)

- Identifiable fetal parts may be present

Invasive mole:

- Similar to complete mole, but involves myometrium

- Choriocarcinoma

- Invasive, malignant trophoblastic disease

- Metastatic can be fatal

Risk factors:

- Cause is unknown

- History of prior molar pregnancy

- Age early teens or >40 years

Signs and symptoms of a molar pregnancy include vaginal bleeding, often brownish (“prune juice”), the passage of hydropic vesicles, anemia (due to loss of blood), uterine enlargement greater than expected, markedly elevated serum hCG levels, severe hyperemesis gravidarum, absence of fetal heart tones, and preeclampsia occurs in 70% of women with large, rapidly growing moles.

Diagnosis of gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD) is via ultrasound which will identify hydropic vesicles. Treatment includes dilation & curettage (D&C), a hysterectomy may be indicated if the woman has completed childbearing, has bleeding in excess, and/or reducing the potential for malignancy is necessary. Rh immune globulin for Rh-negative women at the time of D&C. Choriocarcinoma is treated with chemotherapy. Women are highly encouraged to use reliable contraception for a full year after a hydatidiform pregnancy and discouraged from considering another pregnancy for a least that year due to hCG monitoring and an increased risk for malignancy with the molar pregnancy. In 20% of the clients with the gestational trophoblastic disease, malignant disease (choriocarcinoma) may occur. Baseline chest x-rays will be done. hCG levels will continue to be followed for one year (high or rising levels suggest that metastatic trophoblastic cells are secreting hCG) Effective hormonal contraception is very important (COCs or Depo). Malignant GTD is curable if diagnosed early and treated appropriately.

Late Pregnancy Bleeding

Late pregnancy bleeding occurs after 20 weeks of gestation. As mentioned previously vaginal bleeding at any time of pregnancy should be considered a threat and investigated thoroughly. Causes of late pregnancy bleeding include placenta previa and abruptio placenta.

Placenta Previa

In placenta previa, the placenta is improperly implanted in the lower uterine segment. Implantation can be on a portion of the lower uterine segment or over the internal os. Placenta Previa is cllassified as low-lying, marginal, partial, complete (“marginal” Previa—edge of the placenta is at the margin of the internal os). Excessive maternal blood loss due to placental separation from the lower uterine segment

Incidence and cause:

- Occurs in 1 of 200 pregnancies

- Specific cause unknown

- Associated risk factors include:

- Prior cesarean birth

- Recent spontaneous or induced abortion

- Advanced maternal age

- Smoking

- Large placenta (multiparity, male fetus)

Diagnosis of a placenta previa is an ultrasound.

The pregnant client presenting with a placenta previa will present with:

- Bright red vaginal bleeding

- No pain

- Uterine tone soft and relaxed

- Fetal heart tones usually present unless severe bleeding has occurred

NEVER do a cervical exam on a patient with undiagnosed bleeding! The treatment depends on type of previa, gestational age when bleeding first occurred, and the amount of bleeding. The nurse will monitor fetal heart tones via an external monitor. If severe bleeding is occurring, the nurse will need to prepare for an emergency cesarean section. If no bleeding after diagnosis, expectant management in a patient < 37 weeks includes “pelvic rest” (avoidance of intercourse; nothing in the vagina) with an at term, delivery that will take place by scheduled cesarean.

Abruptio Placentae

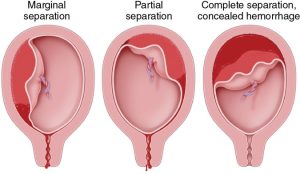

Abruptio placentae is premature separation of the placenta from its site of implantation after 20-weeks but prior to delivery. Bleeding into the decidua results in hemorrhage and placental separation, it complicates approximately 1% (10/1000) of pregnancies and accounts for 15% of all perinatal mortality. It is diagnosed based on clinical impression and post delivery pathology analysis. Characteristics of an abruption include dark red vaginal bleeding (port wine) external or concealed, painful, rock hard abdomen and extreme uterine tenderness, characteristic uterine contraction pattern similar to tachysytole. In severe forms, blood may accumulate behind the placenta and invade the myometrium, turning the uterus blue known as Couvelaire uterus. The uterus does not contract well and may lead to a hysterectomy. Retroplacental clotting and damage to the uterine wall can also occur. large amounts of thromboplastin are released into the blood supply and can trigger DIC and hypofibrinogenemia. The specific causes are unknown but there are risk factors that could place the pregnant client at higher risk for an abruptio placenta. Associated maternal risk factors are hypertension, preeclampsia, abdominal trauma, cigarette smoking, cocaine use (the hypertension and increased levels of catecholamines caused by cocaine abuse are thought to be responsible for a vasospasm in the uterine blood vessels that causes placental separation and abruption), multiple gestation, sudden decompression of the uterus, maternal age > 35 years or < 20 years, previous abruption, chorioamnionitis, presence of fibroids, and subchorionic hematoma. An abruption can be classified as a partial abruption with external hemorrhage, central abruption with concealed hemorrhage, and/or complete abruption with concealed hemorrhage (Beckman & Lings, 2019). Additionally it may be classified on a scale of 0-3.

Nursing care of the client presenting with an abruption is significant to ensure the provider is notified of the significance. The nurse will assess vaginal bleeding, uterine tone and contractions. Fetal heart tones for loss of variability and/or late decelerations. Obtain a IV access per the provider orders with a large bore catheter for possible blood administration, provide supplemental oxygen, monitor coagulation studies, type and cross for 2 units of blood, provide ongoing support and information to the client and family, be prepared for an emergency cesarean section in moderate to severe cases, and monitor for signs of hypovolemia and shock. Signs of shock include hypotension, oliguria, rapid/weak pulse, shallow respirations, pallor, and anxiety. Because normal blood pressure varies from person to person it is important to know the baseline blood pressure for the pregnant client when evaluating for hypovolemic shock.

Risks to the pregnant client suffering from an abruption include hemorrhagic shock, DIC, hypofibrinogenemia, hysterectomy, renal failure and death. Fibrinogen is an essential clotting factor (Factor I). Perinatal mortality is approximately 25% overall—in severe cases where 50% of the placenta has separated, mortality is 100%. Fetal risks include fetal distress, fetal demise, preterm birth and neurological injury.

| Characteristic | Placenta Previa | Placental Abruption |

| Magnitude of blood loss | Variable | Variable |

| Duration | Often ceases within 1–2 hours | Usually continuous |

| Abdominal pain | Absent | Present, often severe |

| Fetal heart rate pattern on electronic monitoring | Normal | Tachycardia, then bradycardia; loss of variability; decelerations frequently present; intrauterine demise not rare |

| Coagulation defects | Rare | Associated, but infrequent; disseminated intravascular coagulation is often severe when present |

| Associated history | Placenta previa in a prior pregnancy (4%–8% recurrence); prior cesarean delivery or other uterine surgery; multiparty; advanced maternal age; cocaine use; smoking | Chronic hypertension, preeclampsia; multiple gestation; advanced maternal age; multiparty; smoking; cocaine use; and chorioamnionitis. Trauma is also a major risk factor, and patients involved in a vehicle accident (even if wearing a seat belt), fall, or other trauma should be evaluated for the possibility of abruption. |

Diabetes in Pregnancy

Diabetes in pregnancy can present as either 1) pre-gestational Type 1 with the inability to produce insulin by the pancreas or Type 2 diabetes where a defect may have occurred with the secretory system creating insulin resistance, or 2)gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) where intolerance to carbohydrates with an onset during pregnancy. Gestational diabetes is classified as class A1 where two or more abnormal values on the oral glucose tolerance test with a normal fasting blood glucose and can be controlled with the diet. The second classification is class A2 where diabetes may have been unknown prior to pregnancy but now needs medication for control.

Early in the pregnancy estrogen, progesterone and other hormones stimulate insulin production to build glycogen stores, which can lead to hypoglycemia in the first trimester. In the second half of the pregnancy, the placental hormone human placental lactogen (hPL) causes maternal peripheral resistance to insulin. This is a glucose-sparing mechanism that ensures that there is glucose for the developing fetus. The pregnant client metabolizes fat (lipolysis) for energy and produces ketones as a result. This is why screening takes place between 24-28 weeks of pregnancy. With gestational diabetes, an increase in glucose levels with the pregnant client circulates increased glucose to the fetus in turn the increased fetal levels of insulin act as a growth hormone causing the fetus to put on extra weight.

Screening and Diagnosis

All women of low to average risk are screened between 24-28 weeks gestation with the 1-hour 50-gram glucose challenge test (GCT). Pregnant clients that are at a higher risk are screened as early as possible. Risks include the client that may present with morbid obesity, strong family history, history of GDM in a previous pregnancy, history of macrosomia, and/or history of intrauterine fetal demise (IUFD). If the result of the 1-hour GCT is greater than or equal to 130-140, a 3-hour 100-gram (GTT) will be done to diagnose. GDM is diagnosed if two or more of the following values are met or exceeded:

- Fasting 95 mg/dl

- 1-hour 180 mg/dl

- 2-hour 155 mg/dl

- 3-hour 140 mg/dl

Management of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus

The goal for the management of GDM is to maintain an equilibrium of insulin and glucose to ensure a healthy client and fetus. Glucose monitoring will be implemented with the ideal fasting glucose at <95 and 2-hours postprandial <120. The pregnant client with the initial diagnosis will be educated on how to manage their diet and beginning regular exercises like walking or low resistance exercises. If the diet does not work they may need to be placed on medications. Typically glyburide or Metformin are used for oral medication. If those do not work the pregnant client may need to be placed on injectible insulin, keeping in mind that the need for insulin may increase as the pregnancy advances. the role of the nurse is to help educate the client and assist with monitoring blood glucose levels. In the hospital, they will assist in the management of insulin oral or injectibles based on the client’s need and provider orders. The pregnant client is advised to monitor to evaluate fetal status by conducting daily kick counts beginning at 28 weeks. The provider will begin nonstress tests weekly starting at 32 weeks gestation once or twice a week. If the NST is non-reactive the provider may order a biophysical profile (BPP) to assess fetal well-being. An ultrasound is conducted at 18-20 weeks and again at 28 weeks to monitor growth and might be repeated as often as every three to four weeks. The maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein (MSAFP) is collected between 15-20 weeks to detect neural tube defects.

Maternal Risks

The pregnant client can be at risk for a number of complications associated with GDM or diabetes including hydramnios, hyperglycemia and ketoacidosis, preeclampsia/eclampsia, labor dystocia, recurrent infections related to hyperglycemia and retinopathy.

Fetal Risks

Risks may also impact the development of the fetus and the newborn after delivery. Perinatal mortality is three times higher in pregnant clients with diabetes. Congenital anomalies have a higher incidence of occurring in clients with pregestational diabetes. Congenital anomalies due to maternal hyperglycemia can occur during organogenesis impacting 5-10% of the developing organs such as the heart, CNS, and skeletal system. The fetus may experience intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), macrosomia, trauma, unexplained demise, spontaneous abortion, prematurity, hypoglycemia after birth, respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), hyperbilirubinemia, and hypocalcemia. RDS appears as a result of the inhibition of some fetal enzymes necessary for surfactant production by high levels of fetal insulin. Hyperbilirubinemia is a result of polycythemia that interferes with the liver’s ability to metabolize bilirubin. Polycythemia results from a lack of oxygen related to elevated glycosylated hemoglobin. Hypocalcemia in the newborn has an unknown cause but may be related to the correlation between insulin with calcium, which may lead to irritability and tetany.

Hyperemesis Gravidarum

Hyperemesis gravidarum is severe nausea and vomiting during pregnancy which may lead to dehydration, weight loss, electrolyte imbalance, and acid-base imbalances. It is related to the rising chorionic gonadotropin and estrogen levels. If uncontrolled the pregnant client may end up hospitalized for IV hydration and antiemetic therapy. The client will be NPO until vomiting stops and the diet slowly advanced. The nurse will monitor the client’s intake and output as well as daily weights and will educate them to conduct the same until they are no longer experiencing vomiting. Treatment for hyperemesis gravidarum may require prescription medications but might be controlled by eliminating foods that may trigger the spells such as spicy or fried foods. Additionally, the pregnant client may try to increase their intake of ginger-containing foods like ginger ale, or ginger tea and take vitamin B6 25 mg BID. If none of the suggested works the provider may prescribe antiemetics such as Zofran ODT, or Diclegis. The nurse can also suggest eating smaller meals to help minimize feeling full due to decreased gastric emptying.

Heart Disease

Congenital heart disease is the most common form of complicating pregnancy. Women with congenital heart disease, unlike in past years, are now living to their childbearing years. Examples of these include Marfan syndrome, pulmonary stenosis, coarctation of the aorta, bicuspid aortic valve. Acquired heart disease is less common but is increasing along with the increased numbers of heart disease in women within the United States. Examples include mitral stenosis (related to rheumatic fever), mitral regurgitation, aortic stenosis. Serious cardiac complications affect 1% of pregnancies. Risks during pregnancy do not cause significant long-term ill effects. However, more studies are being conducted regarding the impact of preeclampsia due to its multisystem pathology.

The blood pressure of the pregnant client drops during the second trimester in response to decreased systemic vascular resistance, with a 30-50% increase in intravascular volume and cardiac output. This increases the heart rate by 15-20 BPM and increases the risk of thromboembolism. During delivery, the volume has a dramatic shift causing an increase of cardiac output of an additional 50% during labor. These changes in the cardiovascular system during pregnancy are poorly tolerated by myocardial dysfunction or valvular lesions. The hypercoagulable state can impair cardiac reserves. The drop in blood pressure can increase the flow across right-to-left shunts like the tetralogy of fallot. Risks are associated with pregnancy in the client with heart disease and are classified by the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification of heart failure and range from Class I (mild) with no detectable increased risk to Class IV (severe) with an extremely high risk of maternal mortality and morbidity and pregnancy is contraindicated.

Management of the pregnant client is to minimize stress and decrease the workload on the heart. The nurse should educate the client on the signs and symptoms of cardiac decompensation during each prenatal visit. Signs and symptoms include fatigue, shortness of breath, palpitations, edema, and cough. Treatment for all infections promptly and take all medications as prescribed. Most are safe during pregnancy, coumadin and ACE inhibitors are contraindicated.

During delivery, the management of the client with heart disease will include several interventions dependent on the classification. THe pregnant client with functionally mild disease (Class I) may be managed the same as a normal pregnant client. For the pregnant client with questionable adequacy of heart and circulation (Class II or III), labor should be induced under controlled conditions. Use mechanical means of ripening the cervix (E.g. Cook’s balloon). Risk of coronary vasospasm or arrhythmias with misoprostol (Cytotec) may occur and continuous fetal monitoring is recommended. Epidural anesthesia is preferred, it helps to lower pain-induced elevations of sympathetic activity, reduces the urge to push—the client should NOT push (Valsalva maneuver can increase the workload on the heart). Fluids should be monitored closely, blood pressure and heart rate should be monitored closely, Swan-Ganz (pulmonary artery) catheters are not routinely used but may be indicated in severe cases. The fetal head should be allowed to descend on its own (“laboring down”), assistance with forceps or vacuum as needed. Cesarean delivery should be done only for obstetrical indications. Several risks include general anesthesia which can lead to hemodynamic instability associated with intubation and anesthetic agent, blood loss greater than with vaginal delivery, increased risks of wound infections and postoperative thrombophlebitis, and incisional bleeding frequent in patients on anticoagulants. There are also risks to the fetus with the client with heart disease including premature birth, intrauterine fetal demise, small for gestational age, intraventricular hemorrhage, and neonatal death.