2

Are there specific ethical considerations arising from researching ‘in the open’? This part of the book will encourage open researchers to reflect on the wider implications of being open as well as approaches to ethical research.

As part of their training, all researchers learn about how to collect, manage, analyse and disseminate data. This section covers the some of things they typically learn about ethics. It is not intended to replace formal training in research ethics although some training modules like these are available openly and will be referred to later. We’ll work through the process in stages.

Our focus here will be on the differences openness can make to these research practices. As we will see, openness can raise problematic cases for traditional approaches to research ethics but also offers novel research possibilities.

Learning Objectives

- An overview of ethics and its role in research

- Developing a better sense of ethical frameworks and how they are applied

- Applying these frameworks in traditional and open approaches across the life of a research project

- Reflection on the process of institutional approval for research and legal compliance

- Creating tools for evaluating ethical risks in a research project and identifying appropriate action(s)

2.1 Why are Research Ethics important?

Most of the interesting questions in life are about people, and as a result a lot of research is done into people: how they behave, what they think, and how they learn and communicate. As a subject for research, human beings are of course quite different to a chemical in a test tube or a rock sample. The moral value of human life requires us to treat others with respect for their wellbeing.

Watch the following short video: Robert Levine (Yale School of Medicine) on the importance of ethics for research involving human subjects.

Activity 5: Thinking about research ethics (20 minutes)

What kind of research do you want to do? What might the impact on human subjects be? Think of three ethical issues that might be raised by the research you want to carry out.

Commentary

There are lots of different potential reasons that research ethics are important. Some of the reasons people gave when we ran the moderated version of the course included:

- Understanding the ultimate impact of our work on humans, and especially the capacity to cause physical or psychological harm through experiment

- Ethical use of time, especially if working with others

- Trying to get the best “impact” from research activity

- Aspiring to professionalism in research practice: protecting participants; improving skills; promoting reliability and validity

- Understanding what kinds of open and public data can be used ethically in research

- Responding to the evolving ethical and practical challenges presented by new technologies: open data; social networking; privacy; anonymity; etc.

These are all good answers, some more pragmatic in focus than others. At the practical end of the spectrum we’ll be looking at specific guidance shortly. But for now it might be good to reflect on the idea that research ethics is a very recent field – and one that was founded in recognition of the profound importance of the way that human beings treat one another. Most of the time educational research involves people as sources of data. Whenever people are involved we need to take care to ensure that they do not undergo any significant harm. We can understand research ethics as a set of principles (e.g. “do no harm”) or as a set of specific rules that can guide us in specific situations.

Some people thought that if they weren’t doing research that could have an obvious impact on human well-being – such as medical or psychological research – then they were less exposed to ethical risks. There may be some truth in this, but the range of possibilities for harm are typically broader than this. We also have to think about privacy, data security, and the longer term implications of sharing research. This is why institutional ethical codes usually refer to experiments that involve human subjects in any capacity rather than just those taking part specifically in medical or psychological experiments. Even information about a person that might seem trivial or inconsequential can have ethical consequences.

2.2 Institutional Research

Usually ethics is addressed in institutional research by adhering to the ethical guidelines set out by one of the advisory bodies that exists for almost every public entity that might be conducting research at some point (e.g. the guidance published by BERA or NIH). These bodies in turn are typically informed by medical ethics as expressed in the Helsinki Declaration (composed in 1964, partly as a response to the unethical research practices that surfaced in the aftermath of World War II). Institutional Review Boards – the term used to describe institutional research ethics approval committees in the USA – are a direct descendent of this declaration.

Central to most institutional research ethics are guidelines relating to all stages of the research process and what can and can’t be done. There are institutional rules, but there are also various forms of guidance offered by research governance bodies.

The following table (adapted from Farrow, 2016) highlights the principles underlying the guidance offered by three major UK research governance bodies: the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC); the British Educational Research Association (BERA); and the British Psychological Society. While the wording can vary, most of the advice given is quite consistent. This is because most research ethics guidelines can trace a common origin back to the aftermath of World War II.

| Principle | ESRC (2015) | BERA (2011) | BPS (2010) |

| Respect for participant autonomy | Research participants should take part voluntarily, free from any coercion or undue influence, and their rights, dignity and (when possible) autonomy should be respected and appropriately protected. (ESRC, 2015:4)

|

Individuals should be treated fairly, sensitively, with dignity, and within an ethic of respect and freedom from prejudice regardless of age, gender, sexuality, race, ethnicity, class, nationality, cultural identity, partnership status, faith, disability, political belief or any other significant difference. (BERA, 2011, §9) | Adherence to the concept of moral rights is an essential component of respect for the dignity of persons. Rights to privacy, self-determination, personal liberty and natural justice are of particular importance to psychologists, and they have a responsibility to protect and promote these rights in their research activities. (BPS, 2010:8) |

| Avoid harm / minimize risk | Research should be worthwhile and provide value that outweighs any risk or harm. Researchers should aim to maximise the benefit of the research and minimise potential risk of harm to participants and researchers. All potential risk and harm should be mitigated by robust precautions. (ESRC, 2015:4)

|

Researchers must recognize that participants may experience distress or discomfort

in the research process and must take all necessary steps to reduce the sense of intrusion and to put them at their ease. They must desist immediately from any actions, ensuing from the research process, that cause emotional or other harm. (BERA, 2011, §20) |

Harm to research participants must be avoided. Where risks arise as an unavoidable and integral element of the research, robust risk assessment and management protocols should be developed and complied with. Normally, the risk of harm must be no greater than that encountered in ordinary life, i.e. participants should not be exposed to risks greater than or additional to those to which they are exposed in their normal lifestyles. (BPS, 2010:11)

|

| Full disclosure | Research staff and participants should be given appropriate information about the

purpose, methods and intended uses of the research, what their participation in the research entails and what risks and benefits, if any, are involved. (ESRC, 2015:4)

|

Researchers who judge that the effect of the agreements they have made with participants,

on confidentiality and anonymity, will allow the continuation of illegal behaviour, which has come to light in the course of the research, must carefully consider making disclosure to the appropriate authorities. (BERA, 2011, §29)

|

This Code expects all psychologists to seek to supply as full information as possible to those taking part in their research,

recognising that if providing all of that information at the start of a person’s participation may not be possible for methodological reasons […] If a proposed research study involves deception, it should be designed in such a way that it protects the dignity and autonomy of the participants. (BPS, 2010:24)

|

| Privacy & Data Security | Individual research participant and group preferences regarding anonymity should be respected and participant requirements concerning the confidential nature of information and personal data should be respected. (ESRC, 2015:4)

|

The confidential and anonymous treatment of participants’ data is considered the norm

for the conduct of research. […] Researchers must comply with the legal requirements in relation to the storage and use of personal data as set down by the Data Protection Act (1998) and any subsequent similar acts. (BERA, 2011, §26)

|

All records of consent, including audio-recordings, should be stored in the same secure conditions as research data, with due regard to the confidentiality and anonymity protocols of the research which will often involve the storage of personal identity data in a location separate from the linked data. (BPS, 2010:20)

|

| Integrity | Research should be designed, reviewed and undertaken to ensure recognised standards of integrity are met, and quality and transparency are assured. (ESRC, 2015:4)

|

Subject to any limitations imposed by agreements to protect confidentiality and anonymity, researchers must make their data and methods amenable to reasonable external scrutiny. The assessment of the quality of the evidence supporting any inferences is an especially important feature of any research and must be open to scrutiny. (BERA, 2011, §46)

|

Research should be designed, reviewed and conducted in a way that ensures its quality, integrity and contribution to the development of knowledge and understanding. Research that is judged within a research community to be poorly designed or conducted wastes resources and devalues the contribution of the participants. At worst it can lead to misleading information being promulgated and can have the potential to cause harm. (BPS, 2010:9)

|

| Independence | The independence of research should be clear, and any conflicts of interest or partiality should be explicit. (ESRC, 2015:4)

|

The right of researchers independently to publish the findings of their research [is] linked to the obligation on researchers to ensure that their findings are placed in the public domain and within reasonable reach

of educational practitioners and policy makers, parents, pupils and the wider public. (BERA, 2011, §40)

|

The ethics review process should be independent of the research itself […] this principle highlights the need to avoid conflicts

of interest between researchers and those reviewing the ethics protocol, and between reviewers and organisational governance structures. (BPS, 2010:27)

|

| Informed Consent | Informed consent entails giving sufficient information about the research and ensuring that there is no explicit or implicit coercion … so that prospective participants can make an informed and free decision on their possible involvement […] The consent forms should be signed off by the research participants to indicate consent. (ESRC, 2015:4)

|

Researchers must take the steps necessary to ensure that all participants in the research

understand the process in which they are to be engaged, including why their participation is necessary, how it will be used and how and to whom it will be reported. Social networking and other on-line activities, including their video-based environments, present challenges for consideration of consent issues and the participants must be clearly informed that their participation and interactions are being monitored and analysed for research. (BERA, 2011, §11)

|

The consent of participants in research, whatever their age or competence, should always be sought, by means appropriate to their

age and competence level. For children under 16 years of age and for other persons where capacity to consent may be impaired the additional consent of parents or those with legal responsibility for the individual should normally also be sought. (BPS, 2010:16) |

Table 1. Comparison of ethical research advice, UK professional bodies (categorized according to underlying principle)

Download a PDF, Word or RTF version of the above table.

Activity 6A: Institutional Approval of Research (1 hour)

Find a copy of your own institutions ethical review procedure (sometimes called ‘Institutional Review Board’ or ‘IRB’). You could then compare this with review procedures at other institutions, or just read it to see what strikes you as noteworthy. Here are some key questions to guide this activity:

- Are procedures more or less the same across institutions?

- What kinds of things seem to be the main concerns?

- How do institutional reviews try to assess the risk of a particular activity?

- What kind of strategies for managing risk are proposed/possible?

- Are there difference across institutions?

- Are there differences across subject areas / disciplines?

If you’re not at an institution then you could find one that might apply to you in the future or one from an institution that is near to you.

If you can’t find one then you can use the information provided by The Open University: OU Ethics Principles for Research Involving Human Subjects.

Commentary

It’s somewhat rare to find a research institution that does not have a code of institutional ethics (at least in the Global North). But this is not to say that there is much diversity: most institutional research ethics codes are the same everywhere around the world, even where they aren’t written down formally. This is partly because there’s a shared family tree – all the different institutional codes express very similar principles.

One difference is legal compliance, which obviously varies according to country. Institutional review should ensure that any research carried out is legal, but it should also go beyond this, asking whether the work can be ethically justified. So, what’s the difference? Many things are legal but arguably unethical, such as adultery, sharing private correspondence, failing to keep promises, jumping queues, and so on. Institutional review is intended to maintain the highest ethical standards, not just compliance with the law.

What happens when you’re not affiliated to an institution that has an ethical review panel? You might be working with open data with no-one to supervise the project in this way. Does this entail that everything you do is ethical as long as it is legal? We’ll consider this in more detail in the next section.

Activity 6B – Protecting Human Subject Research Participants (Optional, 3 Hours)

One common expectation made of researchers in the USA is that they will have completed the online training module ‘Protecting Human Research Participants’ provided by NIH Office of Extramural Research.

The training module is a great overview of research ethics and completion also enables you to produce a certificate of completion which is often needed for institutional ethics review.

You can find the training at https://phrp.nihtraining.com. It’s free and takes about three hours to complete. Completion of this training module is required by many institutions in order to receive ethical approval to conduct research.

2.3 Research in the Institution and Beyond

As an open researcher you will need to ensure that you have any required institutional permissions in place for the work that you want to carry out. Once these permissions are in place then the rules of the institution should be followed. They will normally define the kinds of behaviours that are acceptable. However, it should not be assumed that any behaviours not specifically mentioned (or forbidden) in institutional guidance are acceptable.

If working outside institutional processes (e.g. using Facebook or other social networks to connect with adult learners) you should take every precaution to make sure that your research adheres to the principles of ethical research. Generally speaking, it’s not enough to simply get institutional ethical approval at the start of a project.

- Institutional approvals typically focus on protection of individuals rather than groups

- Research activities can change significantly over the course of a project

- Open projects can have many variables beyond the control of the researcher

It’s important to continue to think about the ethical implications of research as a project evolves. Similarly, if you’re doing research with informal learners (e.g. a survey of MOOC users) and no institutional approval is required you should still strive to consistently apply the same basic principles that underlie standard modern research ethics:

- Avoiding harm

- Ensuring that consent is informed

- Respecting privacy and persons

Next we’ll think about how we might observe these principles if we are working completely outside of institutions and have no requirement to gain permissions for a research project.

Activity 7: Ethical Implications of Openness (1 hour)

Consider the following text from Wikipedia on the definition of ‘open research’:

Open research is research conducted in the spirit of free and open source software. Much like open source schemes that are built around a source code that is made public, the central theme of open research is to make clear accounts of the methodology freely available via the internet, along with any data or results extracted or derived from them. This permits a massively distributed collaboration, and one in which anyone may participate at any level of the project.” (Source)

Now consider the suggestions for an open research process available here.

Do you think that there are potential ethical issues raised by the suggestions made for ‘open research’? Would they be covered by the principles outlined in the previous activity? If not, are there new principles that we need to use when working ‘in the open’ (without institutional rules)? What might they be?

Commentary

Networked, digital and open technologies present us with new possibilities for thought and action. It’s become much easier to do make decisions that can affect a lot of people, as we saw in the Facebook example.

It is essential that the open researcher understands how to evaluate the ethical significance of their work. The simplest way to do this is to understand the principles of research ethics. A simple list of these principles is provided in Farrow (2016)[1] as:

- Respect for participant autonomy

- Avoid harm / minimize risk

- Full disclosure

- Privacy & data security

- Integrity

- Independence

- Informed consent

How ethical principles are applied is context sensitive, so it’s important to keep reflecting on how these inform your work. An important element of ethical judgment is familiarity with ethical issues and how they are usually dealt with. Sharing your experiences with other researchers can be helpful. If you’re working without formal support you will need to strike a balance between the exciting possibilities of ‘guerilla research’ and the need to exercise good ethical judgement throughout the research process.

Sometimes the impulse to be open can be in tension with our ethical expectations. One course participant raised the example of making research data available openly while protecting the right to privacy of participants. The more raw data is released, the greater the risk to privacy. But as more data is redacted the reuse value is reduced. Because the full implications of being open are often not known until the future, it’s necessary to keep reflecting throughout the research process and into dissemination.

In essence, working outside institutions means that researchers must effectively function as their own review panel. It becomes even more important to engage in ethical reflection and develop a working knowledge of ethical risk management and strategies for amelioration.

Most of the rules concerning how research is conducted in institutions are based on several key assumptions. These include:

- The researcher has some degree of control over the research process, and thus has a responsibility for what happens – but can’t necessarily anticipate every possible outcome

- There is an expectation that all reasonable efforts will be taken to minimise potential harm to participants

- The responsibilities of the researcher don’t end with the study since there is an ongoing requirement to manage collected data at most institutions (typically a matter of legal compliance)

- There may also be rules regarding how the research is disseminated, who it can be shared with, and so on

Openness can make a difference across the entire research cycle:

- Building a research community through blogging and social media to generate and share ideas for research activities

- Using openly published papers to perform a literature review and context for a study

- Sharing proposed methodologies for peer comment (e.g. on a blog)

- Collaborating with other researchers to collect data

- Dissemination through open access publication; sharing data sets; publication under a Creative Commons licence

- Improving the visibility of work through repositories, search engine optimisation and sharing on social media

- Inviting quick and responsive feedback

- Using metrics to establish the impact of a piece of research

When it comes to releasing research data openly it’s important to reflect carefully. Both qualitative data (interviews, observations, etc.) and quantitative data (survey results, statistics, etc.) can be released in this way but arguably qualitative data might be less meaningful when considered outside of its original context. There’s no way to anticipate what might happen to data that is released openly because it can used by anyone for whatever reason they see fit.

If you’re planning on releasing data openly that should be made very clear in your consent forms so that people can know what they are agreeing to.

References

[1] Farrow, R. (2016). A Framework for the Ethics of Open Education. Open Praxis, 8(2), 93-109. doi:10.5944/openpraxis.8.2.291

2.4 ‘Good’ Open Research

Given that we can’t always fully anticipate the specifics of future situations it’s especially important for open researchers to be aware of future possibilities. There is a real need for using one’s own judgment and reflecting on the ethical dimensions of research for oneself. When working in the open – potentially beyond institutional reach – an awareness of ethical principles and how they should be applied is essential.

We might say that thinking for oneself about ethics is characteristic of a ‘good’ open researcher.

What other kind of qualities, skills or attributes might a ‘good’ open researcher have? Are they the same qualities that we would expect of a non-open researcher? What does ‘good’ open research look like? What might be the benefits? Either think it through yourself, research online, or discuss with friends or colleagues.

Commentary

This was probably the exercise that learners on the moderated presentation of the course found hardest. It possible to interpret the question of what makes a good open researcher in two different ways. A more abstract approach might involve identifying the characteristics and personal qualities of such people. There are several examples of where researchers have tried to identify these. For instance, Pring (2002)[1] frames the virtues of educational researchers in terms of: positive interdependence; individual accountability; promoting success; trusting relationships. Toledo-Pereyra (2012)[2] suggests the following qualities: interest, motivation, inquisitiveness, commitment, sacrifice, excelling, knowledge, recognition, scholarly approach, and integration.

The report Responsible Conduct in the Global Research Enterprise [3] suggests that there are seven overlapping values for researchers:

- Honesty

- Fairness

- Objectivity

- Reliability

- Skepticism

- Accountability

- Openness

It’s noteworthy that openness can be seen as a distinct consideration in this way, even if one has no interest in openness as a specific concern. The need to have a certain transparency about the research process and any findings is a long-standing scholarly virtue.

References

[1] Pring, R. (2002). The virtues and vices of an educational researcher. In M. NcNamee & D. Bridges (Eds.), The ethics of educational research (pp. 111-127). Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing.

[2] http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22853811

[3] http://bit.ly/2eA3Uf9

2.5. Open Research Summary

So far we have looked at institutional processes governing research and ways in which the same principles might be applied outside of institutional requirements. We also considered the ethical implications of being open and the kinds of virtues we might expect open researchers to have.

It’s not enough to simply know about good research methods: it’s also important to practice them consistently.

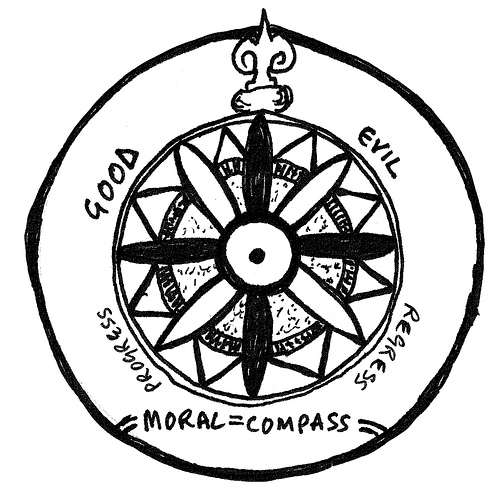

The real point to take away from this part of the course is that open researchers need to be bound by the same ethical codes as traditional research. There is even a case for saying that open researchers need a stronger ethical code because they don’t have the same support as institutional researchers. So it’s crucial that as an open researcher you develop your own moral compass.

A tool that might be useful for this is A Framework for the Ethics of Open Education. Both the principles of research ethics mentioned in 2.2 as well as resources from philosophical ethics are combined in a tool designed to help people think more clearly about the ethical significance of their activities. (For the full paper including a discussion of the complexities that openness introduces into research, see Farrow (2016).

| Duties & Responsibilities

(deontological) |

Outcomes

(consequentialist) |

Personal

Development (virtue) |

|

| Respect for participant autonomy | |||

| Avoid harm / minimise risk | |||

| Full disclosure | |||

| Privacy & data security | |||

| Integrity | |||

| Independence | |||

| Informed consent |

Table 2 – (Uncompleted) Framework

Download a PDF, Word or RTF version of the above table.

Another resource that might be useful is the OER Research Hub Ethics Manual, which was written for an open research project team to facilitate reflection on ethical issues.

Activity 9: Your values and ethical decision-making

Use the materials referred to in Section 2 to help you think about your own values and ethical decision-making processes. Do you act from judgement, or emotion? How do you account for the perspectives of others? Are your approaches to ethics consistent? Philosophical ethics can help us to arrive at answers to these questions.

Since every research project is different you may still have questions or things that you are unsure about. Whether you are based in an institution or not, it’s important to keep thinking for yourself, making judgments about the ethics of research activity and the impact openness can have on research.

Further Reading

- OERRH Ethics Manual

- Introduction to Research Ethics

- Frequently asked questions about human research (The Open University)

- BERA Ethical guidelines for educational research

- Introduction to research ethics (University of Leicester)

- ‘Ethics’, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Peter Singer’s MOOC on ‘Practical Ethics’

- A short introduction to philosophical ethics for research