The Volga German-Russians who were neighbors of the Kirmse and Lohmann families near Goodwin/Shattuck, Oklahoma Territory are described.

the Volga German Russians

There are many resources describing the “Volga German Russians” such as research centers, books and papers. An excellent overall description through the 20th century is given by Wikipedia: Volga Germans[1].

For a focus on the Volga German-Russians who founded a colony in the Goodwin/Shattuck area of the Oklahoma Territory, the following description has been taken directly from Chapter 4 High Plains Deutsch of The WORST HARD TIME – The Untold Story of Those Who Survived the The Great American Dust Bowl written by Timothy Egan[2]:

“Catherine the Great was a German-born empress who married into Russian nobility just after she turned fifteen. By the age of thirty-three, she had dethroned her husband, Peter, and became ruler of Russia. A forceful monarch, Catherine reigned for nearly forty years and was as crucial — indirectly — to settlement of the American Great Plains as the railroad.

Catherine believed that Russia could use fewer Russians and more Germans. A German peasant was not as slovenly as a Russian peasant. Early on, she worried about the frontier on both sides of the middle Volga River, near the cities of Samara and Saratov, in what was then southeastern Russia. She wanted a buffer against Mongols, Turks, and Kirghiz, who roamed and raided the steppe territory much in the way that Apache and Comanche controlled the High Plains. Agricultural colonies, even with people who were not Russian, would bring stability.

Catherine’s manifesto promised free land, no taxes for the first thirty years of a colony, and no military service for male heads of family and their descendants. The manifesto was aimed at all of Western Europe except Jews, who were expressly prohibited from accepting the offer. In the poor villages of southern Germany, where families were broken by the bloodshed and poverty of the Seven Years’ War, Catherine’s representatives found their colonizers. “We need people,” Catherine said, “to make, if possible, the wilderness swarm like a beehive.”

Dozens of villages sprang up in the middle and lower Volga. They were obsessive about keeping dirt from the house; cleanliness was the highest of virtues. If someone spit watermelon seeds onto the street, a punishment of ten lashes followed. Laws required the villages to be clean, the streets swept at least once a week. Each married couple had to plant twenty trees. Upon marrying, the young couple lived with the bride’s family until land was reallotted upon the patriarch’s death.

By 1863, a century after Catherine’s manifesto, there were nearly a quarter-million Germans living on either side of the Volga River. Another group, primarily German Mennonites, had populated higher ground near the Black Sea. Between obsessive street cleaning and house sweeping, the Germans sang. On cold Russian nights, song warmed the stone walls of churches, and it was one of the things that most impressed outsiders. What the colonists on the Volga would not do is become Russian, and this ultimately led to their exile. Russians had grown increasingly resentful of the Germans in their midst, with their snug villages, big harvests, nationalistic pride, and continued exemption from military service. Why special privileges for them?

In 1872, Czar Alexander II revoked Catherine’s promises, declaring that German-speaking Russians had to give up their language and sign up for the army. He raised taxes and took away exclusive licenses to brew beer. Both were fighting causes. For American railroads, fighting constant debt and the fallout of a speculative bubble, the czar’s orders could not have been more fortuitous.

Drought and a grasshopper plague ravaged the American Plains in the early 1870s. “In God we trust, in Kansas we bust” was the slogan on banners draped on wagons of people who had tried to grow something and had given up. On marginal lands in Kansas and Nebraska, farmers were walking away and denouncing the railroads for promoting fraud.

Facing bankruptcy, the railroads found their salvation on the steppes of southern Russia. Their agents in the immigration racket had some experience with Germans and saw them as good clients: they traveled in groups, paid on time, and were considered hard working and thrifty. Some railroads practiced selective ethnic shopping. Burlington printed brochures in German, for example, but not French or Italian. At the same time, reconnaissance groups of Germans were returning to the Volga with firsthand accounts of the land in the middle of America. They liked what they had seen of the Canadian prairie, the Dakotas, and all the way down the plains into the Indian Territory of Oklahoma. It was brutally hot, when it wasn’t cold enough to freeze eyelids shut. It was treeless, windswept, and free. The Promised Land — all over again, just like Russia.

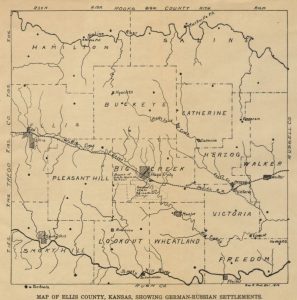

Beginning in 1873, villages folded up and left for the Great Plains. Katherinenstadt, Pfeifer, Schoenchen, and others became near ghost towns. The Germans boarded small boats on the Volga to Saratov. From there, it was a train ride to a North Sea port where they took immigrant vessels to New York, Baltimore, or Galveston and boarded trains for the flatlands. … Some Germans arrived with little more than a yellowed picture of Catherine the Great and a note pinned to their coat, indicating a family or destination. Before long, in places like Lincoln, Nebraska, or Ellis County, Kansas, more German was heard in the streets than English. In the 1870s, about 12,000 Russian Germans came to Kansas; within fifty years, 303,000 would populate the Great Plains. Often the new towns were given the name of the villages they had left behind. In Kansas, Germans established Liebenthal, Herzog, Catherine, Munjor, Pfeifer, and Schoenchen” …

These nesters preferred high-top filzstiefel shoes with soft interior linings to cowboy boots, and featherbeds to American mattresses. No house was without schnapps and wurst. In church they sang “Gott is de liebe” and made such a month-long fuss over Christmas that customs in America changed as well. They were a culture frozen in place in 1763 and transplanted whole to the Great Plains.

Without them, it is possible that wheat never would have been planted on the dry side of the plains. For when they boarded ships for America, the Germans from Russia carried with them seeds of turkey red — a hard winter wheat — and incidental thistle sewn into the pockets of their vests. It meant survival, an heirloom packet worth more than currency. The turkey red, short-stemmed and resistant to cold and drought, took so well to the land beyond the ninety-eighth meridian that agronomists were forced to rethink the predominant view that the Great American Desert was unsuited for agriculture. In Russia, it was the crop that allowed the Germans to move out of the valleys and onto the higher, drier farming ground of the steppe. The thistle came by accident, but it grew so fast it soon owned the West. In the Old World, thistle was called perekati-pole, which meant “roll-across-the-field.” In America, it was known as tumbleweed.

“No one thinks of drouth and grasshoppers — everyone is happy and energetic,” the Chicago Tribune reported in a typical dispatch on the kinetic Germans in 1876. They plowed the grass and planted turkey red on land that others had not dared to farm. What struck some of the American yeomen about these Russian Germans was that they liked to sing, and they kept the floors of their simple houses clean enough to dine on. Dust inside the house was something they would not tolerate.

The Russlanddeutschen held onto their religion, their food, their dress, their rituals, their epic family narratives, and their seeds of grain. In America, they learned about baseball, jazz, the tractor, and the bank loan. They were known as tough-nutted pacifists, a migratory people whose defining characteristic was draft-dodging. The German Mennonites from near the Black Sea, conscientious objectors from the beginning, certainly were opposed to war on principle. But many of the other Germans from Russia would kill without flinching, showing their warrior skills in American uniforms when they shot their own former countrymen during the two world wars in the twentieth century. What they would not do is fight for the Russian czar or — worse — fight for the Bolsheviks.”[2]

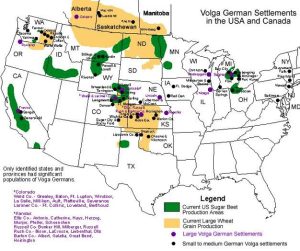

As shown on the following map, there were Volga German-Russian settlements throughout the USA and Canada.

Most were were in wheat grain production and a significant number went into sugar beet production.

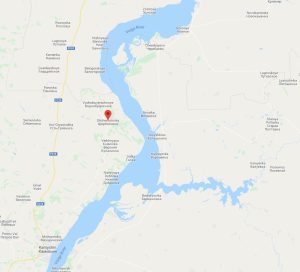

Shcherbakovka – Ehrlich family home town in Russia

Shcherbakovka, (also known as Deutsch Tscherbakowka and Muehlberg between 1917 and 1941), a Lutheran colony on the west bank (Bergesseite (hilly side)) of the lower Volga River, was founded 15 June 1765 by Johann Stricker.

There were two villages by this name–one Russian, one German–both on the western side of the Volga River. The Minkh Russian Encyclopedia (according to David Bagby, 1992) indicates that the towns (both Russian Tscherbakowka and German Shcherbakowka) were named for Michael Shcherbatov, a well-known writer and man of letters during the reign of Catherine the Great. The Shcherbatovs (accent on the BAT) were a prominent Russian noble family.[5]

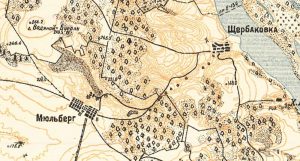

The following 1935 map shows both Shcherbakovkas. German Shcherbakovka (aka Deutsche Shcherbakovka) is on the left; Russian Shcherbakovka is on the right.

Tscherbakowka, the Russian village, was located right on the Volga. The German village lay about five miles west and south of the Russian one. Both are in the province of Saratov (about 95 miles south of the city of Saratov) and in the district of Kamyshin.

Religion

Lutheran

The German Shcherbakovka was founded as a Lutheran colony on 15 June 1765 by the Government. It was the eighth colony established and one of the original (or Mother) colonies located on the lower Volga for the German emigres. The first colonists came from the areas of Durlach, Württemberg, and Darmstadt in Germany. [5]

In 1872, a big wooden church was built for the predominate Lutheran congregation. It could seat 1000. It had a prayer house and connected school. Over the years, the simple wooden buildings were replaced by structures that were quite elaborate with intricate brick/stone work, ornate interiors, and outstanding organs.

The Lutheran church at Shcherbakovka had a bell tower on the left and the gates to the cemetery were on the right. The steeple including the cross was 175 feet. School classes were held on the second floor.[5]

Seventh-Day Adventists

“The relationship of the Seventh-Day Adventist Church with the Volga Germans is different from that of the Lutheran and Catholic colonists because it is not represented in Russia before the emigration. Rather, new converts in America sent tracts about the denomination back to their relatives and friends in Russia which laid the groundwork for the establishment of Seventh-Day congregations in Russia. Copies of Die Stimme der Wahrheit (Voice of Truth), an American Adventist magazine for German immigrants, first reached German settlements on the Volga in 1879.

Conrad Laubhan, an emigrant from Shcherbakovka living in Lehigh, Kansas, returned to Russia in 1886 for twelve years to serve as a leader in the rapid spread of the movement. A well-known Adventist preacher, Ludwig R. Conradi, and Gerhard Perk, a young Mennonite in the Ukraine who had adopted the Adventist faith, made a missionary tour around the Crimea, southern Ukraine, the Volga German area, and the northern Caucasus preaching and baptizing converts.”[6]

Mills

“Because of its location, Shcherbakovka was an ideal site for water mills. At one time, there were 34 mills along the stream which ran below the village and into the Volga River which was about five miles away.” [5] Some were flour mills, others spinning and weaving mills powered by an enormous spring back in the hills. There were also quite a few oil mills, where people brought their sunflower seeds to extract sunflower oil. Shcherbakovka was sometimes called Muhlberg because “there was a canyon and in that canyon was one mill after the other, all driven by the falling water on the mill’s big wheels which turned the grinding stones. ” [5]

Life in Shcherbakovka

“Anna Mollenkamp describes some of the things her father told her about life in Russia. … Their houses were built of either wood or adobe made of yellow clay and racks, using frames as are used for cement houses. The roofs were of shingles. Houses usually had two or three rooms, the main room being about 30 feet long and 20 feet wide. It served as living and dining room and bedroom, with two or three beds along one wall. The kitchen was small. The third room was usually for the elderly parents of the husband or wife. Each place had a summer house and a cellar. The summer house was a few feet from the main house. It had a small fireplace, and in the summer, the food was cooked and eaten there, keeping the big house clean and cool.

A nearby spring covered by a building which had troughs from one end to the other, was where the livestock drank. Clothes were washed at home and brought to the spring for a thorough rinsing.

In the big attic of the house were stored grain, flour, syrup made from watermelons, meat, lard, dried fruit, dried beans and peas. Saurkraut was made in 50 gallon barrels. Cider was made from apples. Blue plums were put down in sugar and let ferment, and the juice was served at mealtime, instead of tea or coffee. The plums were served separately. There were strawberries in season.

Wheat and rye were taken to the mill which was run by water power. There it was ground into flour to be made into bread. It was baked in large outside ovens made of brick. The ovens would hold six big loaves of bread, being six feet long and four feet wide.

Sheep were raised for their wool which was spun and knit by the women into socks,caps, mittens and other garments for the entire family.”[7]

Notes

- Wikipedia: Volga Germans.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Volga_Germans

- Timothy Egan, The WORST HARD TIME – The Untold Story of Those Who Survived the The Great American Dust Bowl. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, New York, New York. 2006. Chapter 4 High Plains Deutsch, page 68.

- Shcherbakovka. Volga German Institute at Fairfield University. https://vgi.fairfield.edu/colonies/shcherbakovka

- Maps of the United States. The Center for Volga German Studies at Concordia University. http://cvgs.cu-portland.edu/archives/maps/united_states.cfm

- Shcherbakovka. Lower Volga Project. http://www.lowervolga.org/Shcherbakovka/index.html

- Seventh-Day Adventist, The Center for Volga German Studies. http://cvgs.cu-portland.edu/history/religion/seventh_day_adventists.cfm

- The Lower Volga Villages, Bauers and Krafts, Lower Volga Project,

http://www.lowervolga.org/Shcherbakovka/shkraft.htm