The Creative Project

7 Project Budgets

Outlining Where the Money Goes

Overview

In this chapter, you learn how to…

- Review the fundamental requirements of grant budgets.

- Identify best practices for formatting budgets.

- Construct a budget that reflect details and logistics to support your project narrative.

In this chapter you will build your project budget. Your budget supports the narrative created by your proposal through a detailed account of how you plan to use the funds you are requesting.

This can feel overwhelming at first. Keep in mind that the budget helps you tell the story of your project from a different perspective. The function of the budget is to show the reviewer that you’ve thought through every detail, including what resources it takes to move forward with your proposal. They want to determine if what you are proposing is feasible in terms of time, talent, and resources.

Building A Budget

We are going to address what it will cost to make your project happen. This will include identifying what you are going to pay yourself. If you haven’t done this before, or become frazzled when trying to put a dollar amount on the value of your time, this is a moment to pause and take a breath—here is your cue:

DEEP breath in.

DEEP breath out.

DEEP breath in.

DEEP breath out.

Repeat as needed.

While figuring out these elements can be challenging, paying yourself, any collaborators, and your project partners is critical to the success of your proposal and the work itself. So roll up your sleeves and let’s dig in.

The process of building a budget helps you create a complete and thorough financial plan for your project. This financial plan is critical to broadly outlining your project management, understanding where you’ll need to invest cost and effort, and demonstrating to your funder that you don’t just have the vision, you have the know-how to make it reality (Creative Capital, 2018).

You might be asking yourself—how can I know what this is really going to cost when I haven’t even begun this project?

Welcome to the wonderful world of building something from nothing. You find the answers to this question by working through your project income and expenses step by step:

- Gather project expenses and income sources.

- Organize expenses and income into categories.

- Assign dollar amounts to each item and category.

Identifying and Organizing Project Expenses and Income

Let’s take the first step towards tackling the budget for your project. Any project budget contains two categories that are fundamental from a financial perspective:

- Project expenses

- Project income

Project expenses are what you need to spend money on to make the work you’re creating happen. This includes equipment, tools, collaborators, and other costs we’ll get to in a moment. Project income refers to anything you receive to support your project, most often in the form of money. This can include grant funding, personal funds, crowdfunding, in-kind donations, and other possibilities which depend on the specific type of project.

Let’s start with the cash that must leave your pockets to make the project “go.”

Artists in Action

“I learned very quickly when I’m making a budget for a grant to make sure that not only are all of my collaborators that are involved in the grant are paid well for their time, but that I’m also paid well for my time. It’s something I learned very quickly, that actually grant panels want to see that you’re also taking care of yourself and that you’re not just going to put yourself into debt by funding this project.”

–Adam Rosenblatt

Identifying the Expenses

Here’s the bottom line. You need money to bring your project to life. By carefully outlining what you need to spend and how it fits into the larger scope of your project, funders can better understand how your project works beyond the narrative of the project description. Ultimately, you want to use your budget to prove to funders that your project is a strong investment of their resources and demonstrate concrete elements that support its proposed impact. The first step to accomplish this is to break down the answer to this fundamental question: What will the money be used for?

What Will the Money Be Used For?

There are a few categories to consider to successfully answer the above question.

Personnel. For collaborators, you need to know and calculate their hourly rates.

- Are you working with other artists or institutions?

- How will they be compensated?

Marketing. Most projects require some marketing and communications to be successful. This can include both physical materials and digital marketing.

- How do you plan to market your project?

- Where do you plan to market your project?

- Which social media platforms and audiences best suit your project?

Facilities. You need to know what it costs to use any space or facility necessary for your project, including performance venue and practice space.

- Does your project require space to be presented to the public, like a recital hall, studio, or gallery?

- What about space required for the creation of the project, like a recording studio, rehearsal space, or filming location?

- If appropriate, where will you store oversized project-related materials such as lighting, sets, or backdrops?

Travel. Be sure to include both travel and lodging costs for personnel, and shipping costs for any necessary equipment.

- Will travel be required to complete the project?

- Will you need to ship project-related equipment or materials?

Materials and Equipment. If you are using your own equipment, you can include that as a cost. You can add to your project income by listing it as an in-kind donation from yourself. If you need to purchase a special piece of equipment to make this project happen, you should include this in your budget as well.

Administration. Administrative efforts require compensation as well. While some grants cover grantee administrative costs, not all grants do. Check the grant’s instructions before you include this in your costs. Whether or not a grant covers these specific costs, it is important to have a clear understanding of the time and cost of the administrative work involved in a project. It is often this work that makes or breaks the success of a project reaching the finish line.

Before we leave this section, some items are non-allowable expenses. Repayment of personal debt, along with routine overhead costs like regularly rented housing, studio space, or office space, are generally not allowable expenses.

Don’t worry about any expenses you forget the first time you draft your budget. You can always come back to this and adjust things. Right now, we’re sculpting in clay and it is malleable. The most important thing is to start breaking these cost areas down and defining them for first yourself and, ultimately, your reader.

Artists in Action

“One of the things that I learned that day is, me needing money is like saying nothing. That’s what everybody says, ‘I need funds!’ What would those funds go to? Be specific.”

– CJay Philip

“Not only do you write the grants, but you’ve got to practice and you’ve got to do the marketing. You’ve got to rent the halls and load the truck and all of the things that go into all that too, right? You don’t have the luxury to not be strategic about how you do your funding.”

– Andrew Kipe

Identifying the Income

Next, let’s outline the funding sources that will support your project. While the grant you are applying for may make up most of the funding for your project, listing other sources of funding and in-kind donations shows that your project will maximize the investment of grant funds. Just as we had to explain what the money is used for, now we need to share with potential funders the other available sources of financial support for the project. We now explore where the money comes from.

Where Is the Money Coming From?

Once again, if we break this down into a few categories, things will quickly fall into place.

Grants or Foundation Funds. This includes all grant funding. This can come from a variety of organizations, including non-profits, foundations, and governments, among others.

Business or Organization Donations. Some businesses and organizations will offer funds or donate space, advertising services, or products, often in exchange for listing and promoting the business as a sponsor.

Crowdfunding or Individual Donations. Funding can include money from a GoFundMe or other crowdfunding campaign, or a personal contribution from a patron, family, or community member.

Personal Contributions. Ask most artists about a project they developed and you will almost always find that part of their journey includes a personal contribution to overcome a funding gap and show an investment in their work. Putting forth some of your own money to create a proof of concept to share with potential funders is not uncommon. It is, in fact, often what helps an artist take the first steps towards realizing the project and building the necessary momentum to go from “nothing” to “something.”

Sale of Services or Products. Depending on the type of project you are developing, you may need to include ticket sales, merchandise, CDs, or anything else that would generate earned income.

In-kind Donations. In-kind donations refer to non-monetary contributions of goods and services for which you would have otherwise paid. For a typical arts grant, this often includes performance space, loaned equipment, or individuals donating their time and expertise. They are important for a couple of reasons:

- Help make the project (or aspects of the project) viable, as financial resources can be limited.

- Show buy-in or support for you and your project from collaborators, organizations, and partners.

This in-kind support can, when used strategically, create additional credibility for your project. This is especially important because some funders may be more inclined to fund projects that show evidence of existing support from other organizations, groups, or individuals. Hopefully it also creates a bit of FOMO (fear of missing out) for the grant panelist and helps convince them to move your application forward in the review process.

Artists in Action

“You now have your artists fees and that’s the one thing I do love about grants. It allows me to do one of my favorite things, which is pay artists– pay my friends.”

– CJay Philip

Categorizing Expenses and Income

The next step is to group your expenses and income into categories that make sense for your project. Categories help tell the story of how your project will work. They also provide an opportunity to include contextual details about equipment, personnel, space needs, and the related financial implications that can be challenging to summarize concisely in a project description.

Expenses

- Personnel

- Marketing

- Travel

- Administration

- Materials

- Value of in-kind contributions

Income

- Crowdfunding

- Grants

- Business donations

- Personal

- Sales

- In-kind contributions

Length and Detail of a Budget

Now that you have your project expenses and income grouped in categories that support your project description, it is time to think about the length and detail of your budget. Take a moment and review the requirements for your grant. Many granting organizations ask for budgets to be no more than one page. Use the whole page to fill in funding details about your project. Keep in mind that correct formatting of your budget and all other submitted materials for your specific grant is a critical first step in the review process.

Too Much Detail to Fit on One Page?

As mentioned above, most funding providers for individual or independent artists require a one-page budget. With that in mind, many of the examples in this section will be structured around a one-page budget model.

Depending on the scope of your project, there may not be enough space on the page to capture all the expenses or income sources that you identified. One solution you can use to meet a single-page budget requirement is to determine which items could be combined without losing detail. For example, rather than listing performer fees by concert, combine them into one budget line item called “performer fees.”

Not Enough Detail to Fill One Page?

Conversely, your project might not have that many elements regarding expenses and income. One approach that can be helpful is to consider ways to break down your costs into more specific items. Rather than one line item for the category of “marketing,” list the different ways you want to market your project, such as using social media, distributing physical posters, or attending similar events to talk with patrons.

Assign Dollar Amounts to Each Item and Category

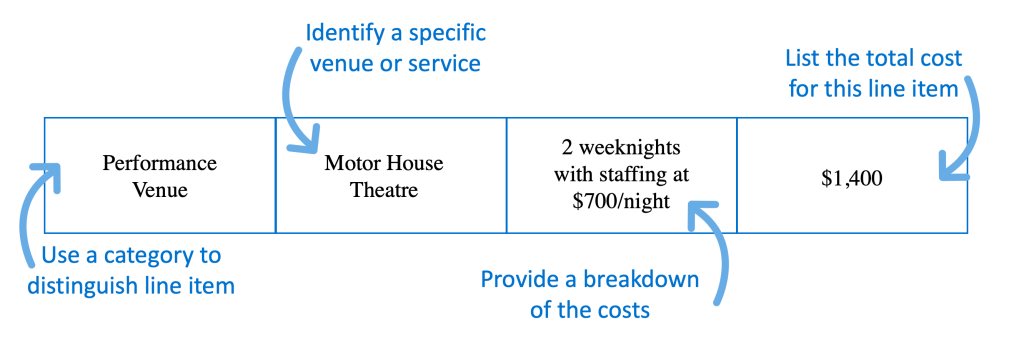

If you are reading these words, then woo-hoo! You have reached the final part of this process and that can only mean one thing—it is time to start assigning dollar amounts to each expense and contribution. These individual expenses and income sources are called line items. Each line item typically includes a category, specific service, cost breakdown or description, and total cost. For example, if you need to rent a performance space, you could list the line item this way.

This process requires two distinct skills:

- Research. This means searching the web for everything about your project like it’s your job (because it is). This includes costs of physical materials related to your project, rehearsal spaces, venues, recording studios, artist fees for co-creators, etc.

- Informed guesswork. Think of this like packing for a long trip with a single bag—you don’t know exactly what the weather is going to be like, but the future you needs to be warm enough, dry enough, and comfortable with whatever the world tosses at you. Now take that metaphor and apply it to dollar amounts.

Ultimately, wherever possible, assign a specific number amount along with a source for your cost. This shows the reviewer that you have a firm idea of the projected costs, and they can count on your ability to complete the project on the proposed budget. It also shows that you did your homework. Sometimes it is impossible to know the exact cost. In those cases, do your best to make an estimate by researching a similar product, space, or service with a known price. In this scenario, it is a research/informed guesswork combination.

Once you have dollar amounts assigned to each of your line items, you can finish assembling your budget. Keep it looking clean by rounding off amounts to the nearest whole dollar. Add up the subtotals for your budget categories and include them as well.

You can continue to modify your budget as your project changes, but the three-step process of identifying expenses and income sources, organizing them into categories, and assigning dollar amounts provides a solid starting point.

Artists in Action

“The best advice that I ever got about fundraising was from Dean Fred Bronstein. He said, ‘Jessica, money follows leadership.’ That was so encouraging to me because it reminded me that if I’m just doing my job well and building relationships in the community and serving, staying focused on the service part of my work, that the fundraising will fall in line.”

– Jessica Satava

Telling the Story through Numbers: Successful Models

In this section, you can review an example budget that needs improvement. Then, you evaluate the revised version to compare the difference. Proposed costs must make sense for the project (or be reasonable), fit acceptable costs established by the guidelines (allowable), and have a specific and definite use (allocable).

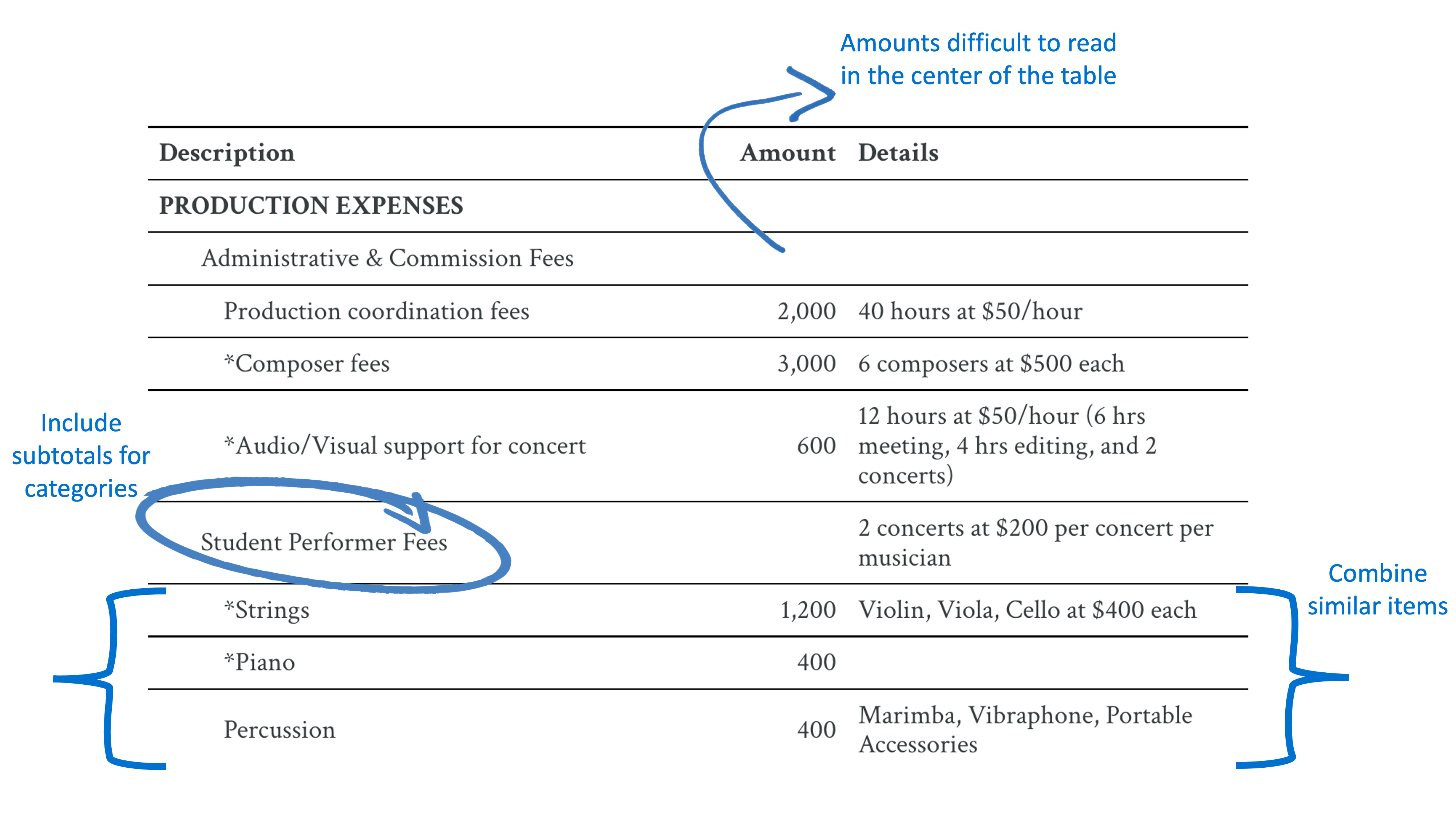

Original Budget

Read through the original budget below to determine if you can catch any issues with the line items or format.

| Description | Amount | Details | ||

| PRODUCTION EXPENSES |

||||

| Administrative & Commission Fees | ||||

| Production coordination fees | 2,000 | 40 hours at $50/hour | ||

| *Composer fees | 3,000 | 6 composers at $500 each | ||

| *Audio/Visual support for concert | 600 | 12 hours at $50/hour (6 hrs meeting, 4 hrs editing, and 2 concerts) | ||

| Student Performer Fees | 2 concerts at $200 per concert per musician | |||

| *Strings | 1,200 | Violin, Viola, Cello at $400 each | ||

| *Piano | 400 | |||

| Percussion | 400 | Marimba, Vibraphone, Portable Accessories | ||

| Winds | 800 | Flute and Clarinet/Oboe at $400 each | ||

| Venues and Transportation | ||||

| ABC Retirement Community venue | 0 | In-kind contribution | ||

| Peabody venue | 0 | In-kind contribution | ||

| Transportation | 100 | Ride shares and percussion transport | ||

| Marketing/Promotion | 200 | Facebook ads, fliers, programs | ||

| Entertainment/Reception | 100 | Post-concert reception at Peabody (ABC venue has no fee) | ||

| Rehearsal snacks | 100 | |||

| EXPENSE TOTAL | $ 8,900 | |||

| Funding Sources | ||||

| Peabody Launch Grant | 5,000 | *Items covered by grant | ||

| ABC Retirement Community | 300 | |||

| Personal Contribution | 400 | |||

| Crowdfunding campaign (GoFundMe) | 1,000 | |||

| Private donations | 2,300 | Solicit donations from retirement community residents | ||

| REVENUE TOTAL | $ 8,900 | |||

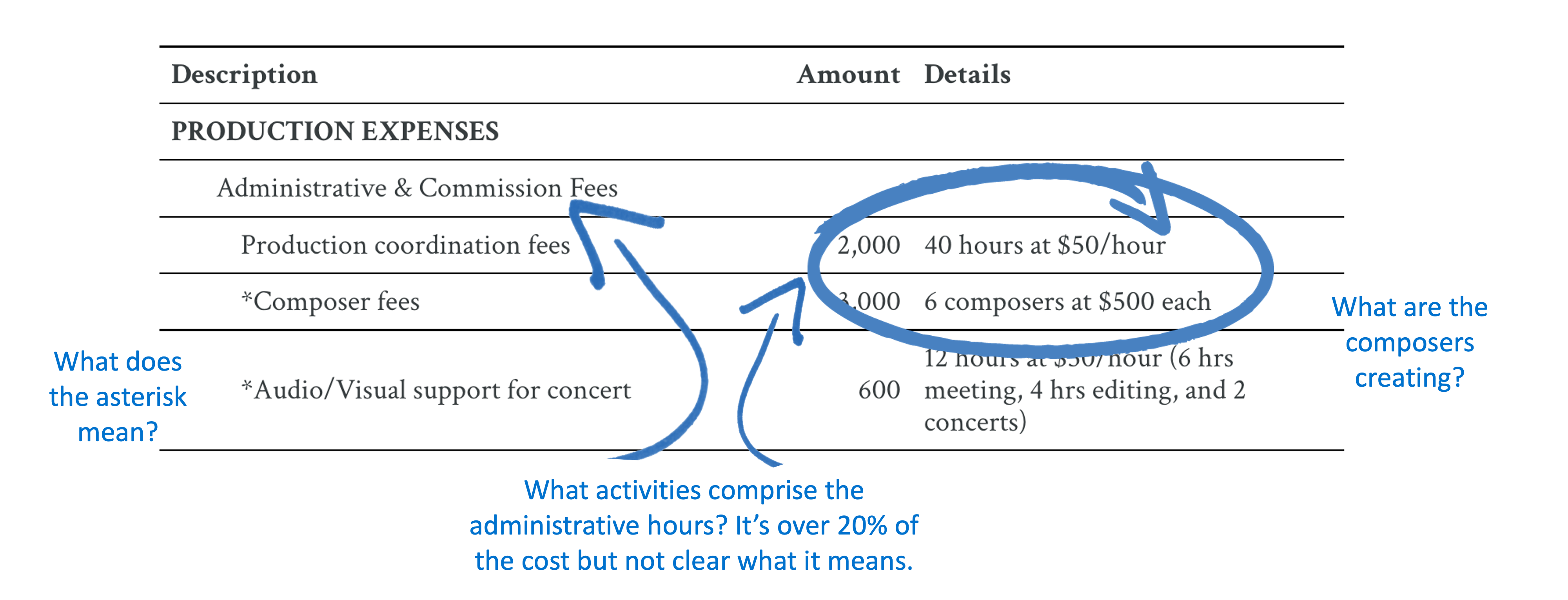

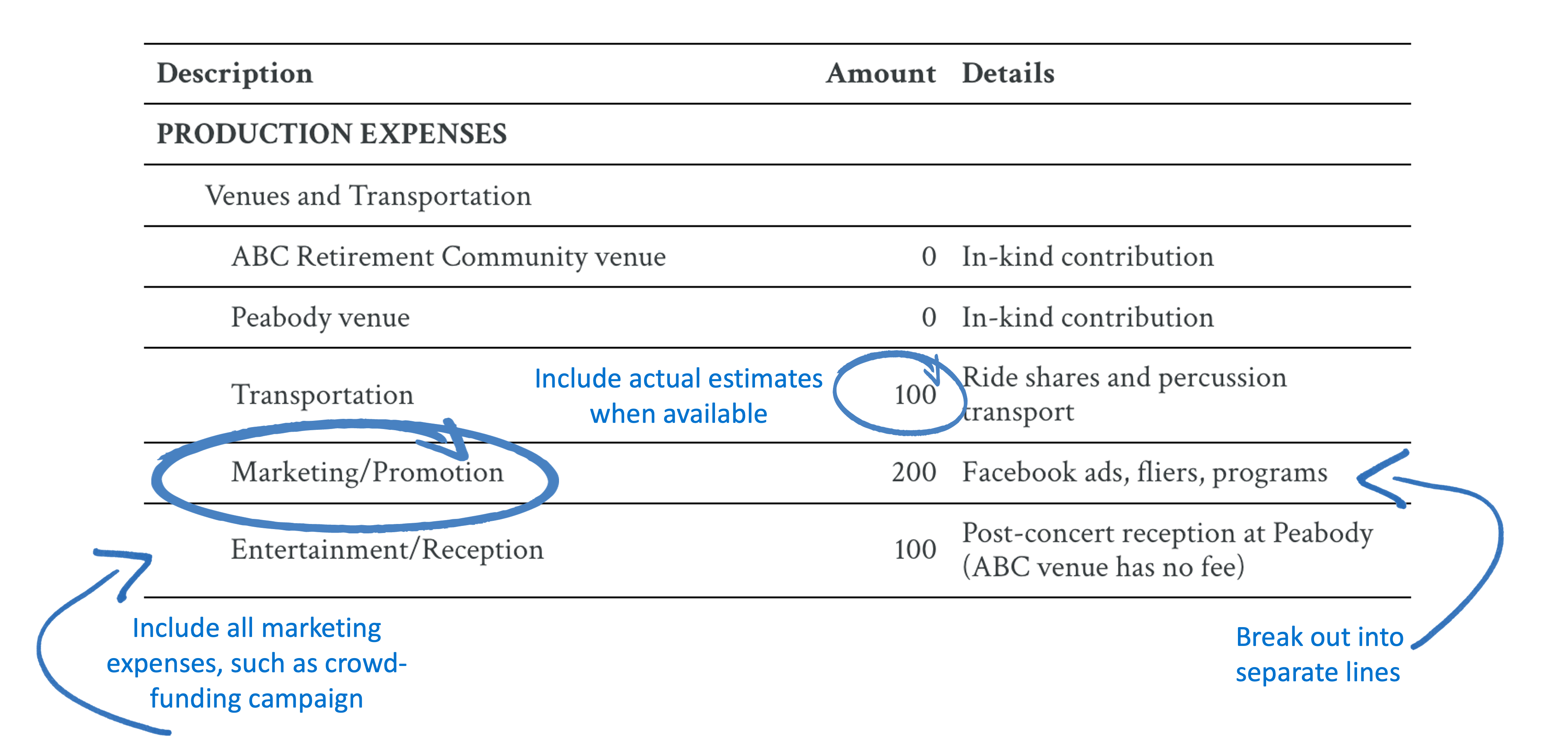

Room for Improvement

Let’s take a critical look at the original budget above.

Format and Organization

- It is easier to read a budget when the total cost is in the far right column.

- The performer costs are similar—combine them to make space for more granular detail elsewhere.

- Using categories is a great way to structure your budget, but make sure to include subtotals for the income or expense of each section.

Specificity

- Be more specific about the administrative needs.

- Be more specific about the compensation for composers. What are they creating?

- Some line items are unclear, such as the Entertainment/Reception line—are the funds already secured? How are they being used?

- When project expenses exceed the total possible grant, many applications require that you indicate what the grant will fund. This could be done more clearly.

Details Matter

- For items with costs that can be reasonably estimated, round numbers like the Transportation line item indicate that the grant writer has not estimated the actual expense.

- Although the Marketing/Promotion budget is small, these expenses would be clearer as separate line items.

- A successful crowdfunding campaign requires active marketing and promotion, which is not indicated in the Marketing/Promotion category.

Fundraising and Donations

- Even when receiving a service or product as an in-kind donation, always list the estimated cost. The in-kind support can then be listed under income or funding sources.

- A personal contribution communicates that the artist has some “skin in the game” and can help reviewers take the artist more seriously. Don’t overcommit yourself. You can also make in-kind contributions to your project.

- A large gap in funding could create concern for a funding committee if not secured.

Revised Budget

The updated budget below includes revisions based on the critiques we just went over. Review how it has changed.

| EXPENSES | Details | Amount | |

| Personnel Costs | Subtotal $ 8,500 | ||

| Production coordination fees | 40 hours at $50/hour for coordinating performances and rehearsals, coordinating meetings, and creating promotional materials | 2,000 | |

| *Composer fees | 6 approx. ten-minute compositions at $500/each | 3,000 | |

| *Audio/Visual support for concert | 12 hours at $50/hour (2 hours meetings, 6 hours editing, and 4 hours setup & recording for 2 concerts) | 600 | |

| *Performer Fees | 7 Peabody student performers at $200/performance | 2,800 | |

| Rehearsal snacks | 100 | ||

| Venues and Transportation | Subtotal $ 402 | ||

| Retirement Community venue | 75 | ||

| Peabody venue | Goodwin Hall at $75/day rental | 75 | |

| Transportation | 3 Ride shares from Baltimore to Towson at $84/round trip | 252 | |

| Marketing and Promotion | Subtotal $ 347 | ||

| Entertainment/Reception | Post-concert refreshments at $75/concert | 150 | |

| Advertising | 10 days of targeted Facebook ads at $10/day | 100 | |

| Printing | Staples, 50 fliers at $20, 250 programs at $77 | 97 | |

| EXPENSE TOTAL | Expense Total $ 9,249 | ||

*Items covered in part by Peabody Launch Grant

| FUNDING | Details | Amount | |

| Peabody Launch Grant | 5,000 | ||

| Peabody Institute | In-kind venue donation of Goodwin Hall | 75 | |

| ABC Retirement Community | Includes general funds and in-kind venue and reception donation | 450 | |

| Private donations | Personally solicited contributions from retirement community members | 2,324 | |

| Crowdfunding campaign | GoFundMe donors gain early access to recordings, as well as process updates and sneak peeks | 1,000 | |

| Personal contribution | 8 hours of production coordination at $50/hour | 400 | |

| REVENUE TOTAL | Total $ 9,249 | ||

Budgets clarify the financial narrative of a project. After reading this example, do you have a clear idea of where the money will come from and how it will be used? Do the costs seem reasonable? Are all the uses specific and clear? Where would you ask this artist for more details, and where do you feel they could save some space?

Exercise 7-1. Project Expenses Brainstorming Activity

In this activity, you’ll brainstorm potential expenses related to your project.

- Find your favorite note taking materials.

- Set a timer for five minutes.

- List out any possible expenses you can think of that you might need to execute your project.

This is just a draft, so no need to be concerned about the order or organization for now. If you get stuck, imagine the project happening in your head and walk through the processes, people, and materials you’ll need to create the final product. Keep adding to the list if you think of things as you advance through this chapter.

Exercise 7-2. Project Income Brainstorming Activity

Just like you did for the expenses, take a few minutes to brainstorm about sources of income for your project. Set your timer for another five minutes. Add a new section to your notes for income. Try to think outside of the box and challenge yourself to be as specific as possible. For example, instead of just writing “individual donors” as a funding source, brainstorm where you might find these donors and how you can connect with them.

As with expenses, appropriate sources of income will depend heavily on the content and goals of your project. If your project is interdisciplinary, consider grants related to all the disciplines that make an appearance. If your project has a social justice theme, research local nonprofit organizations whose missions align that might be able to provide in-kind support. If you are proposing a project that is more ongoing in nature, consider revenue sources that can make your project financially sustainable beyond the original grant funding. Again, this is a work in progress that will continue to evolve along with your project.

Exercise 7-3. Categorize Expenses and Income

Access your notes with your draft list of expenses and income sources from Exercises 7-1 and 7-2. Using the categories in the chapter as a starting place, begin to organize your items into the appropriate groups. Create new groups as needed and remove the ones that don’t fit for your project. The goal is for the categories and individual items in your budget to create a clear picture that helps reviewers visualize how the project will work. More importantly, it shows how the grant funds will be allocated to achieve the intended impact(s).

Exercise 7-4. Pay Rate Resources

One challenge in building a budget can be setting your own rates, or establishing reasonable rates for other artists. The American Federation of Musicians publishes recommended pay scales, shared below.

- American Federation of Musicians[1]

- AFM Los Angeles chapter pay scales[2]

- Nashville Musicians pay scales[3]

Other artistic labor unions (AGMA,[4] SAG,[5] Equity,[6] to name a few) also create pay scale agreements with organizations which you can use to assign values within your budget.

Exercise 7-5. Assign Expense Values

Review the categorized list of expenses you created in Exercise 7-3. Consider the following questions:

- What are the expenses to which you can easily assign precise dollar values?

- Which ones are leaving you stumped?

- Who can you ask or where can go you for more information for those items that you’re less sure about?

Exercise 7-6. Budget Resources

For more information about creating a budget, review these resources:

- Budget Basics for Artist Fundraising[7] provides a detailed overview on building a budget from The Creative Independent.

- Making a Project or Annual Budget[8] provides a detailed process for creating line items for an artistic project from Creative Capital.

- Budget Tips and Samples[9] includes budget tips and samples from Creative Capital.

Key Takeaways

Creating a detailed budget that thoughtfully and creatively reflects your project narrative is imperative to writing a strong grant proposal.

- Your budget is a tool that tells the story of how you will develop your project in terms of resources.

- There are three steps to creating a budget:

- Gather project expenses and income sources.

- Categorize expenses and income.

- Assign specific dollar amounts.

- Your budget should support the narrative created by your proposal.

As you go through the budget creation process, keep these points in mind:

- Your budget should support the narrative created by your proposal. Tell your project’s financial story through your categories, the order of your line items, and details in your descriptions.

- Refer to the grant instructions and guidelines frequently, as they provide the formatting details and expected budget categories.

- Expenses are evaluated on being reasonable, allowable, and allocable. Proposed costs must make sense for the project (or be reasonable), fit acceptable costs established by the guidelines (allowable), and have a specific and definite use (allocable).

Artist Interviews

Below are excerpts from artist interviews conducted by Zane Forshee. Full artist bios and interviews are available in About the Artists. This section includes the following artists and topics:

- Jessica Satava on After the Initial Success, What She Wish She Knew Earlier, and the Day of an Orchestra Director

- Brad Balliett on Iterative Improvements and the Most Difficult Part of the Process

Jessica Satava on After the Initial Success

What did you learn after your first successful grant proposal?

ZF: After your first successful grant proposal, what did you learn? What were your takeaways and then how did that impact or affect the way you went after the next one or the next project?

JS: I think when you’re a musician or when you’re an administrator, we know that time is a limitation. There are so many things that we could be doing with our time, practicing, paying the bills, talking to donors. Sometimes it feels really difficult to devote the time that we need to sit down and write a grant.

But when you get one and it comes through, it gives you that confidence. It’s so renewing and fulfilling to feel like somebody out there sees that I can solve a problem in my community and believes that I have the tools to do that. That is an incredible feeling to know that somebody has confidence, that the work we’re doing is meaningful and [they are] willing to support it with a significant chunk of money. That really means something.

Then it propels you forward to be that much more tenacious and that much more focused on your goals. Then you start thinking creatively. Okay, well, if they would fund that, then what about if we did this next cool thing that we’ve been thinking about and let’s plan for next year and let’s start setting all of this up so that we can be in a really good position to ask again next year from this foundation. Or this foundation has a slightly different spin on it and we can take it in a different direction. It just feels good. It builds your confidence, and you know that you’re not wasting your time.

ZF: I love that. And so, you become more daring and more creative with each step?

JS: Absolutely. The more that you feel like people are getting on board with your mission and your project goals, the more you feel empowered to think more creatively, more innovatively and collaborate with more people.

ZF: Does this tie back to that piece of advice you shared from Dean Bronstein around money follows leadership?

JS: Absolutely. Business as usual doesn’t excite funders, and innovation requires leadership. So, that is 100% a Dean Bronstein advice moment.

Jessica Satava on What She Wish She Knew Earlier

What do you wish you knew when you started?

ZF: So, I want to ask a question then, knowing where you are now in that process, if you could talk to yourself at the beginning of that journey, what would you do differently or what do you wish you knew when you started?

JS: As a classical musician and as a result of the training and the formality of the environment of classical music, at least up till the last couple of years, there’s this barrier, right? Like if somebody gives you a set of guidelines for something, you don’t ask questions, you do everything they say when you’re submitting, like for a competition or something, you follow it to the letter and you hope for the best. You turn it in by the deadline and you hope that all went well and that you’re going to get it. You’re going to get into the competition. And there’s just really no conversation. It’s just, I do what I’m supposed to do and hope that that gets me where I want to go.

What I’ve learned is that the key to all of this is asking questions. So, just kind of working to break down that barrier in our minds, that [misconception that] we can’t have a conversation about these things. The people at these foundations and these granting organizations are there because they care about solving problems and supporting innovation and they want to talk to us. So when I learned that I could call and ask questions, it really was awesome because it did two things:

- It kept me from wasting my time if it wasn’t an opportunity that really was applicable for my organization.

- It helped me build relationships within the foundations and the organizations that were giving, you know, distributing the funding that led to me having an increased opportunity to get some grant money from them.

ZF: That’s a great discovery. So, really going to the source and not being afraid to ask the question.

JS: Absolutely.

Jessica Satava on the Day of An Orchestra Director

What does the day of an orchestra director look like?

ZF: You’ve shared with us the moment where it kind of really clicked for you where like, I want to work in this environment, building this orchestra, this collective sound. If you were to talk about what the job and what the work is, and break it down into categories of what your day looks like, what is it that you’re doing, because some of the work you’re doing is being in front of the orchestra and you’re out in the community representing the orchestra, but then there’s behind the scenes work. And I was wondering if you can talk about some of that world for us.

JS: Absolutely. So, the number one most important part of my job is raising money to ensure that our programs and our orchestra and our artists can be sustained by the organization. I love that because I have to say the best advice that I ever got about fundraising was from Dean Fred Bronstein. I was embarking on my new career and I was kind of transitioning away from Peabody and moving to Johnstown to come and do this work, he said, “Jessica, money follows leadership.”

That was so encouraging to me because it reminded me that if I’m just doing my job well and building relationships in the community and serving, staying focused on the service part of my work, that the fundraising will fall in line, will fall in lock step with all of that.

So fundraising is a major part of it. Of course, then there’s the production side, the artistic operations side. There’s the programming planning, which is super fun. I love the artistic programming side of my work, collaborating with a conductor to bring all of these ideas and this vision that he has for our community to life. That’s incredible.

Of course, there’s lots of logistics. I spend a lot of time writing checks, paying bills, providing financial statements to the board, I spend lots and lots of time working with them to support their leadership in our community and to make sure they have the information they need to make decisions for all of us. I’m a manager. I manage a lot of staff. I manage 70 employees of the orchestra, so I spend a lot of time hearing from people, listening, solving problems. It’s just, it’s such a fascinating job because I honestly get to do everything you could possibly imagine doing. I’ve really learned a lot.

Let’s see. The other thing that I’ve really had a chance to focus on that I never did before coming to this job is marketing and communications, promotional work and PR (public relations) for the orchestra. Setting the tone for the organization in the community through that work has been incredible. I’ve enjoyed that so much. Learning how to use data to drive decisions has been really fun for me.

So what am I missing? I feel like there’s a lot of things that I didn’t tell you, but… oh, oh yeah! The collective bargaining agreement. So, I get to bargain with the union for the terms of our agreement with them, with the orchestra. So, that’s been a really interesting part of my work. I feel like I’m this close to having a labor law degree, or I could, but that’s been really fascinating for me too.

Brad Balliett on Iterative Improvements

Have you ever tweaked an idea from a rejected submission?

ZF: Have you ever had an idea, you believed in the idea, you kept working on the idea, and then you submitted a grant [and] it didn’t get picked up? Then you learned in the process of that, how to tweak it a bit more and resubmit it for another opportunity? Has that ever happened?

BB: Definitely, yes. There’s almost always a grant out there that seems tailor made for whatever project you’re doing. Each grant is almost like a draft for a better version of that same grant, because even the act of typing out what you want to do, how you’re going to spend your money, what you’re going to do the third week versus the fourth week, and how you’re going to assess your success helps to organize your thoughts.

Sometimes it’s just the act of writing a grant that makes you organize some things that you realize, I didn’t have a plan for that! And it’s a darn good thing that I had to write this out, or else I would have been improvising in the moment and thank goodness that didn’t happen.

Honestly, I think if you’re improvising on a grant application, that comes through a little bit. But the next time you write the grant, when you say, well, I thought this through last time I wrote this grant. Then it’s actually your plan and then it turns from improvising into confidence and that confidence comes through. So it’s well worth taking a couple stabs at something.

Besides the fact that there’s no grant I know that does not like to see repeat applicants. A dismissal is really an invitation to try again. And probably most people that ultimately get those big, pie in the sky grants (you know, like National Endowment for the Arts or something), they’ve probably been trying a bunch of times. The people on the committees are probably saying, this is the person or this is the group that’s doing the kind of sustained work that we want to support. How do they know you’re doing the sustained work? Because they’ve seen you applying seven years in a row. They say, well, this has legs, they’re supporting themselves. Now we want to give you some support.

Brad Balliett on the Most Difficult Part of the Process

What part of the grant proposal process do you still find difficult today?

ZF: What part of the grant proposal process do you still find difficult today?

BB: The part that I still find really difficult is probably finding the right words. Because after enough time with a group or as an individual, you have certain work samples that you really stand behind. You feel really personally connected to [them] and you feel like [they] really represent the best of you. That’s a gift because those are kind of untouchable.

You’ve got your recordings, your videos, whatever. It’s that trying to unlock what’s the combination of words that expresses what we’re trying to do? It’s going to get right at the heart of it in a way that the person that’s reading this says, “I understand. And I’m right there with you!” The difficulty is that you just don’t know who’s reading your words. You can have an idea of the set of values that the institution that’s giving the grant stands for and the type of projects they’ve funded in the past, but it is a person that’s reading your words.

There must be a way to still be professional and polished and still feel like you’re talking directly to the person that’s reading these words, that’s going to put it not in this (no) stack, but in this (yes) stack. That’s something that I’m not sure there’s ever going to be an answer for. We have to just do our best every time and kind of throw it up in the air.

References

Creative Capital. (2018, July 19). Applying for grants: Creating a realistic budget. https://creative-capital.org/2018/07/19/applying-for-grants-presenting-a-realistic-budget/

Yudkowsky, E. (2015). “Planning fallacy.” In Rationality: From AI to zombies. Machine Intelligence Research Institute.

- www.afm.org/departments/freelance-membership-development ↵

- https://afm47.org/allscales.html ↵

- www.nashvillemusicians.org/scales-forms-agreements ↵

- https://www.musicalartists.org/ ↵

- https://www.musicalartists.org/ ↵

- https://www.musicalartists.org/ ↵

- https://thecreativeindependent.com/tips/budget-basics-for-artist-fundraising/ ↵

- https://creative-capital.org/2015/02/12/page-handbook-goes-project-annual-budget/ ↵

- https://creative-capital.org/content/docs/Budget-Tips-Examples-2017.pdf ↵

an overview of all expenses and expected sources of income for a project

the process to help define the goals and objectives of the project, determine when the various project components are to be completed and by whom, and create quality control checks

all costs of the project, including funds for marketing, administration, personnel, or facilities; includes planned and actual expenses

the specific funding sources of the project, including grant funds, individual and personal contributions, and in-kind donations; includes planned and actual income

the use of small amounts of money from a large number of individuals to finance a new venture; often uses social media and websites to bring people together, with the potential to increase entrepreneurship by expanding the pool of investors beyond the traditional circle of owners, relatives, and venture capitalists

a non-monetary contribution of goods and services; see in-kind support

a grant document which describes your project in detail, sharing what the project is, why it is important, who is involved, and how it will be accomplished; sometimes called a statement of grant purpose, executive summary, or project summary

the generally indirect expense like personal debt repayment, housing rental, or rental of studio space

an item listed in a budget, such as the cost of electricity

the proposed costs that make sense for the project

any acceptable costs established by the guidelines

any costs with a specific and definite use

any non-monetary support, such a contribution of a venue, equipment, time, labor, or supplies; see in-kind donation