The Artist

3 Project Ideas

Developing What You're Going To Do

Overview

In this chapter, you learn how to…

- Demonstrate and strengthen ideation methods and skills.

- Create a mind map related to your project.

- Develop strategies to get yourself “unstuck” from anchor problems.

Earlier you considered who you are as an artist, the artistic work you create, and how it aligns with your mission and values. Now, we can turn our attention towards what you want to develop.

Perhaps you already have a clear idea of what it is you want to create. If that’s the case—great! On the other hand, you may not be sure what you want to develop or may be feeling stuck. Regardless of where you are in this process, we will be using mind mapping, a technique to help you generate ideas, visualize them, and connect them together.

While there are other tools and strategies available to generate ideas, this chapter focuses primarily on mind mapping.

Defining Mind Maps

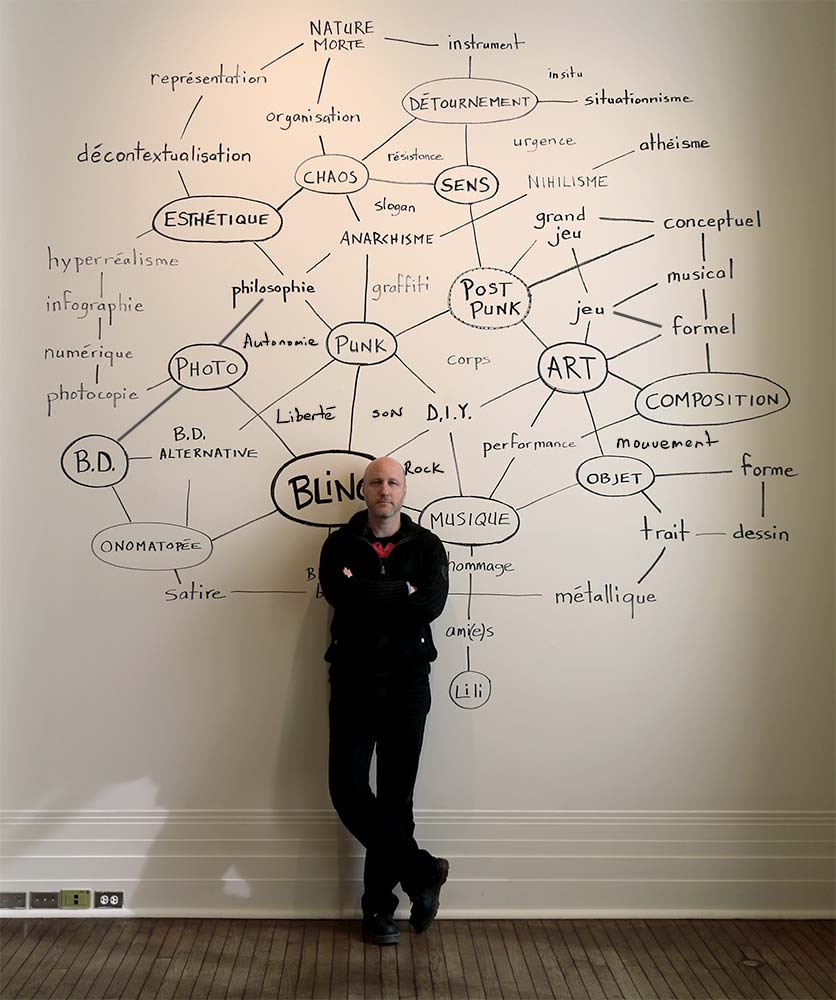

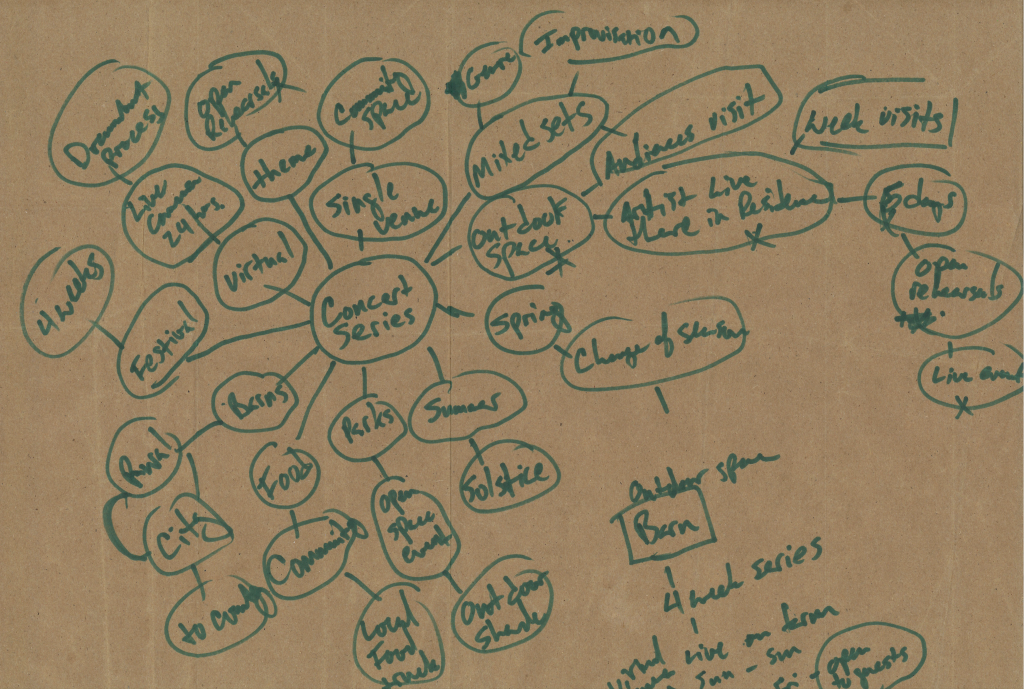

At its core, a mind map is a diagram that is developed, often in a freehand fashion, to capture ideas visually, organize them in a hierarchical manner, and discover relationships between disparate pieces within the whole. Mind maps typically emerge from a single concept placed at the center of a page and used as a vehicle to generate material for potential solutions to a problem or a challenge (AF Bureau, 2020).

“A Mind Map is a diagram for representing tasks, words, concepts, or items linked to and arranged around a central concept or subject using a non-linear graphical layout that allows the user to build an intuitive framework around a central concept.”[1]

Below is are two examples of a mind map.

Why Mind Mapping?

“The way to get good ideas is to get lots of ideas and throw the bad ones away.”

—Linus Pauling, American chemist

Why should you use mind mapping?

This process of idea generation, or ideation, allows you to rapidly develop possibilities. The more ideas that you might want to explore, the greater the chances of creating a better idea, project, or design.

The development of more possibilities creates greater access to innovative projects, ideas, designs and collaborations. This process is about creating and developing ideas—not just the obvious ones, but the wild and unexpected ideas.

“The greatest originals are the ones who fail the most, because they’re the ones who try the most. You need a lot of bad ideas in order to get a few good ones.”

—Adam Grant, American organizational psychologist

Letting Go – Where the Wild Ideas Are

We get through life by making judgments—judgments about the fastest way to the store, what we want to eat, what our next project will be, or what to wear. Sometimes we think through these judgements, but other times they happen at the edge of or outside our awareness without letting us consciously take time to consider the decision (social scientists refer to this as heuristics). These unquestioned judgments help us live our life efficiently, but they can put up roadblocks for our imagination.

Busting out of our patterns of thought allows us to create novel solutions and ideas, but how do you let go? One method is to embrace the impossible:

- What would happen if aliens could see your project or problem?

- What would happen if it was on the moon?

- How would you create your project if gravity suddenly stopped working?

Playfully answering absurd questions is an excellent way to reset your mind for ideation work. Feel silly—don’t take anything seriously. There’s plenty of time for that later.

Artists in Action

“I saw lots of companies in Baltimore for adults. I saw way more companies for children. But the thing that I saw around the country when I was on tour was this disconnect between the generations and a disconnect between parents and children that I thought the arts could reconnect. Because in my opinion, you don’t age out of creativity, and I don’t feel like the arts is a drop off service for your children to go be creative and meanwhile you’re struggling as an adult to even remember the creative human within you.”

– CJay Philip

“I think it’s made a big difference for me just psychically to know that I have these other people with me and that we can do more together than I could do on my own.”

– Lara Pellegrinelli

Generating Project Ideas

The first step to coming up with ideas is letting go—letting go of self-judgment, letting go of the exciting ideas we may have already fixated on, and allowing yourself space. Modern models of creativity divide the process into a “production” phase and a “judgment” phase. However, judgment can often overtake our production of ideas and keeps us from generating a wealth of possible ideas (Puccio, 2018).

Think about your artistic practice—you likely already have methods for generative work and evaluative reflection. How do you separate them? This is easier said than done, so let’s share some techniques to help you stay in the idea-creation phase.

One of the simplest tools is a five-minute timer. How often when trying to solve a problem or come up with ideas do you give yourself space to move past your first functional solution? Giving yourself five minutes to think of ideas ensures you can think past the first thing that comes into your head (Yudkowsky, 2015). Spend the time capturing any idea you have on paper or another preferred device. We’ve worked this technique into several chapters, so you’ll have chances to practice.

Making a Mind Map

“Success is a function of persistence and doggedness and the willingness to work hard for twenty-two minutes to make sense of something that most people would give up on after thirty seconds.”

—Malcolm Gladwell, Outliers: The Story of Success

Let’s walk through the mind mapping process. We find mind mapping to be a great ideation tool for several reasons. Mind mapping relies on the free association of words, allowing all possible ideas to come to the surface. As a visual and tactile process, it can stimulate a wider range of connections.

When making your mind map, encourage yourself to move quickly, capturing whatever comes to mind. This works to overcome your inner critic and ensures you capture a lot of ideas for your project. The goal is not just ideas, but also possible links between your different ideas.

You can use software or go analog to create your mind map. Butcher paper, a flattened-out paper bag, or a chalkboard are all great options. Use what’s available and allows you to make the largest, wildest map of your ideas.

Artists in Action

“It is not easy to come up with a concept that maybe no one else really understands, maybe you don’t feel like you can even explain it with words. Then sort of take that concept and work on it for six months or a year and come up with a finished product. That’s difficult to do. It’s challenging, but it’s also an extremely rewarding experience.”

– Wendel Patrick

“Just be yourself. They want to see who you are and why you’re doing this and your excitement. Your passion about the project is going to shine through, and that’s going to show commitment. Don’t lose that authentic personal touch because it’s a piece of paper.”

– Christina Manceor

Three Simple Steps to Creating a Mind Map

Follow these steps for creating a mind map (Kent State Online, n.d.).

- Choose an idea (Exploring the potential)

- Generate possibilities (Creating layers)

- Create connections (Mining the ideas)

Step 1: Choose an Idea (Exploring the Potential)

To begin, take your idea, project, or challenge and place it at the center of what will become your mind map.

Step 2: Generate Possibilities (Creating Layers)

- Draw three to five lines that extend off the central point you are interested in exploring. If you’ve circled your main idea at the center of your page, the image might begin to look like a drawing of the sun.

- Set a timer for two to three minutes. By giving yourself a time constraint, you provide a means to keep you from censoring your ideas. Go for quantity, not quality.

- Write down single words, short phrases, and ideas.

- They can be wild, far fetched, or beyond what might be feasible.

- Now repeat this process by building off the first round of ideas that you generated. Continue to repeat the process until you have three to four layers of word associations.

- Keep in mind that you want to move through this entire process of creating layers and word associations quickly. Doing it quickly, with a time limit, keeps us from censoring ourselves and capturing all of our ideas.

If you give yourself lots of time, you can draw the process out through self-censoring and editing. In contrast, a time constraint forces you to generate options in just a few minutes. Think about a time you procrastinated, perhaps for an assignment that you waited to the last minute (at some point we have all done this!). Somehow, almost magically, you can crank out that huge paper during a late night of burning the midnight oil and get it turned in on time. The same principle applies.

Step 3: Create Connections (Mining the Ideas)

This is where it gets interesting! Review your mind map for keywords, phrases, and ideas that excite you. Mash these ideas together and see what new connections, ideas and concepts emerge. The true value of this process is often found hidden in the outer layers of the mind map—the places where you’ve pushed beyond your inner critic to let the wild ideas emerge.

Artists in Action

“Usually, it starts with a very small kernel or core of an idea. Frequently it’s just a piece, one [musical] piece that I’m really crazy about trying to perform. But usually, I realized for myself, if I just can’t get this one idea or piece out of my mind, I know it’s the start of something. But I found that the mistake I made in the past was I had this one kernel, and I thought that one kernel was enough of an idea to just start looking for funding.

There’s that one thing that I just can’t get out of my head, whether it’s an idea, a piece, a collaboration I think would be really interesting. I just kind of let it sit for a little while. I’m now kind of imagining this as a whole, complete experience rather than part of an experience. Then I feel comfortable to move forward to the next step. And sometimes that can take a long time.”

–Adam Rosenblatt

Getting Unstuck

In their book about design thinking, Bill Burnett and Dave Evans describe a set of problems they call anchor problems. These are problems that keep you stuck in your thinking—they hold you back from being able to move forward with building your idea. Below are some examples:

- “I can only perform this piece with a full 50-person orchestra.”

- “I don’t know anyone who will support this work.”

- “I don’t have enough relevant experience to create this type of creative work.”

- “People aren’t interested in what I do.”

Anchor problems feel intractable, and outside your control. This is where we get back to wild ideas—how can you reframe the problem to find novel solutions? Imagine you are a wildly different person, an animal, or an alien—then how would you approach the problem? What would happen if it wasn’t an issue, and you imagine your project past the problem?

Importantly, Burnett and Evans (2016) recognize there is a difference between anchor problems and problems stemming from facts about the world, which they call gravity problems. The sun is down at midnight, artists earn less than CEOs on average, and water makes things wet. These are problems to recognize and design around, rather than reframe.

Exercise 3-1. Design Thinking

“Design thinking is a human-centered approach to innovation that draws from the designer’s toolkit to integrate the needs of people, the possibilities of technology, and the requirements for business success.”

—Tim Brown, Executive Chair of IDEO[2]

Mind mapping is used in the human-centered creative problem-solving process called design thinking. Described by Bill Burnett and Dave Evans (2016) from Stanford’s d.school,[3] design thinking provides a methodology for empathetic problem solving.

Exercise 3-2. Original Thinkers

Organizational psychologist Adam Grant studies “original” thinkers who dream up new ideas and take action to put them into the world (Grant, 2016). Watch his 15-minute TED Talk “The Surprising Thinking of Original Thinking,”[4] where he shares three unexpected habits of original thinkers, including procrastination and embracing failure.

Exercise 3-3. Ideation Tools

To explore more idea generation tools, check out this article by Alcor entitled “Idea Generation – Techniques, Tools, Examples, Sources And Activities.”[5]

Key Takeaways

While this chapter focused on mind mapping, there are also many other tools out there to help with idea generation! Find the tools that work best for you and use them throughout the process of formulating your project and writing a grant proposal.

Key points include the following:

- Taking the time to ideate and brainstorm more ideas equips you to create better solutions.

- Don’t just choose the first idea that comes to mind; instead, try to silence your inner critic to let new ideas through.

- Use a mind map to generate and organize ideas about your project.

- Watch out for anchor problems that can make you feel stuck—reframe or approach them from another perspective to move forward.

If you don’t have clarity as to exactly what your project is going to be, that’s okay—this is a process that takes time. Keep working through the mind mapping process or other ways you might have of generating ideas to help you define what it is you’d like to create.

Artist Interviews

Below are excerpts from artist interviews conducted by Zane Forshee. Full artist bios and interviews are available in About the Artists. This section includes the following artists and topics:

- Alysia Lee on Her Philosophy on Grants Applications

- Khandeya Sheppard on Transitioning From Idea to Event

Alysia Lee on Her Philosophy on Grants Applications

After getting a grant, do you start getting more approvals?

ZF: After that initial success of that first grant, obviously the confidence boost, because people like my idea, people support my idea. But then does that mean that right after that it was home run after home run in terms of getting more grants, or did you have some sort of up and down with that?

AL: I would say there’s two pieces to that. I’m very picky about the grants that I apply for. Not everybody can be picky about that. There are two schools of thought, some people will apply for grants that are a little bit on the periphery, right? That might be pushing it a little bit, because you still might get those funds, right?

I’m not that way. I tend to apply for grants where, when I submit the grant, I am almost certain I’m going to get it. And that is a risk aversion of mine, because of my time capacity. I run a very small ship. So to me it’s like, if I’m going to invest 12 hours, I want to know that you’re going to send me $50,000 when I’m done. I tend to work that way.

There’s a network of people who have funded us. People who are funding us. I’m always asking this question, who else do you know that might be interested in learning about our work? Creating that network of folks who are supporting us is a big thing. And also, just really getting in touch with the folks at the foundations in advance. You know, the Maryland State Arts Council is iconic for this. The recent Maryland State Arts Council, which has all new staff, their grants manager is happy to get on the phone with you and talk through and read your grant application and give you some feedback on it. That’s not always been the case, but foundations are getting better at being more transparent and helping people to elevate their work so they can find the best ideas, not just the best proposals, right?

So, with that in mind, you can talk to these people before. Never send a grant application to someone you haven’t spoken to. Talk to the people at the foundation first. Let them get to know your work. If you can, think about it two years out. Like, right now I’m thinking of the exact foundation that just published their grantees. And I read through the list, I was like, it’s our time. We want to apply in two years, so this season and last season we’ve been inviting them to shows. I’m not applying this year. I’m sure they’re going to be like, “where’s your application?”

But we’re not ready yet. I know that we’re not ready, our project isn’t big enough, the budget isn’t big enough for this match. So, we’re inviting them to things, they’re getting to know us, they’re meeting our singers. You know, you can date people for a while too. So that when you propose, you don’t want to propose marriage to somebody, and they say no. You want to know before you pull out the ring at the baseball stadium in front of the cameras and your whole family is there and her family is backstage, you want to know when you say, will you marry me?, the girl is going to say yes. So that’s the same thing. That’s my philosophy, but other people do have a different philosophy. And if you have more capacity to produce more grant applications, then that’s a great thing too.

Khandeya Sheppard on Transitioning From Idea to Event

How do you go from idea to the pitch to an event?

ZF: So, one of the things I see as tricky is that period where you’re like, “I’ve got the vision and I’m going to go into the embassy and I’m going to have this meeting.” If your life was anything like mine, you’re like, “I’ve got an idea and I know how to be really organized, but I have nothing in my hand to put in front of you. I don’t have a brochure. I don’t have a poster.”

- What is it?

- How did you frame that to get someone to say yes?

- What was your pitch?

How did you come at that to walk in to a place like that and just say, “This is what I want to do,” and walk out with, “Yes, we want to come with you.”

KS: This is going to sound really silly to a lot of people, but it works. I think that number one–this is not the silly part–number one, do your research, research, research, research. Look at different types of proposals, different proposals that you’ve seen before, things that you may not have known are proposals. There are different websites out there–LAUNCHPad[6] has some–that show you how to write a proposal to do a pitch.

The silly part is I watched [the television show] Shark Tank[7] a lot. But honestly, and I’m glad I made you laugh, but the key to having a successful pitch is watching other people do it. Not just Shark Tank; I use Shark Tank as an example. The more that you see the process and the action of doing it and the types of questions, this is where I get my input, the types of questions that come back from the panelists on something such as Shark Tank.

They may ask for more information than the person was prepared to give. That helped for the preparation of the process to go to someone like the embassy and say, “I need to have a thousand of these things kind of clearly aligned in my head for myself.” So that if the question should present itself, I have an answer. If it doesn’t, that’s fine.

But I need to number one, talk to somebody like the ambassador about what the benefits are for the embassy being involved in my project, especially as I’m coming in as a new endeavor of Dynamic Steel. I had to show them my expertise and my experience before. I had to come to the table with that. I had to have it clearly written out as well, and be comfortable speaking with someone engaging in the conversation. I had to lay out how that aligns with what they have going on right then and there, and that’s where my research came in.

Because since that new ambassador had been put in place, his charge was to try to be more heavily involved and promote more community driven things. I thought that that aligned perfectly with what he was aiming to accomplish in that timeframe. This is one of the events that could be a part of this process:

- Having all of those things clearly written down

- Looking at a lot of different proposal templates

- Figuring out which one was the best one for me to present this type of idea

- Using my background knowledge of having watched a lot of Shark Tank

- Being ready for the curve ball questions to come and being prepared to answer them

I think that made the experience better for me going in, because I felt a lot more prepared to handle any types of questions, even if I didn’t have the answer yet, to handle those types of questions when it came time.

References

AF Bureau. (2020, August 22). Idea generation: Techniques, tools, examples, sources and activities. Alcor. https://alcorfund.com/insight/idea-generation-2/

Burnett, B. & Evans, D. (2016). Designing your life: How to build a well-lived, joyful life. Alfred A. Knopf.

Gladwell, M. (2008). Outliers: The story of success. Little, Brown and Company.

Grant, A. (2016). Originals: How non-conformists move the world. Viking.

Grant, A. (2016, April). The surprising habits of original thinkers [Video]. TED Conferences. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fxbCHn6gE3U

Kent State Online. (n.d.). Assignment type: Mind maps. Kent State University Office of Continuing & Distance Education. Creative Commons CC-BY Attribution International 4.0. https://www-s3-live.kent.edu/s3fs-root/s3fs-public/file/Mind_Map_Handout.pdf

Mindmapping.com. (2022). What is a mind map? Mindmapping.com. https://www.mindmapping.com/mindmap

Puccio, G., Cabra, J., & Schwagler, N. (2018). Organizational creativity. SAGE Publications.

Yudkowsky, E. (2015). “The third alternative.” In Rationality: From AI to zombies. Machine Intelligence Research Institute.

the process of creating a diagram to capture ideas visually, organize them in a hierarchical manner, and discover relationships between disparate pieces within the whole; often developed in a freehand fashion

a diagram that is developed, often in a freehand fashion, to capture ideas visually, organize them in a hierarchical manner, and discover relationships between disparate pieces within the whole

the process of creating new ideas

methods of thought consciously or subconsciously used to solve problems, which can vary in their effectiveness for different tasks

a stubborn obstacle in your problem solving or ideation process which may feel unsolvable and keep you from imagining novel solutions

a problem defined by immovable circumstances, either because they are beyond your control or because you are not willing to change them