2 Your College Experience

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify the risks and rewards of college.

- Understand the principles of academic integrity.

- Identify differences in class delivery and compare strategies for success in each type.

- Identify different categories of students who might share the same classroom as you.

- Identify similarities and differences between different types of students compared to yourself.

The Risks And Rewards Of College

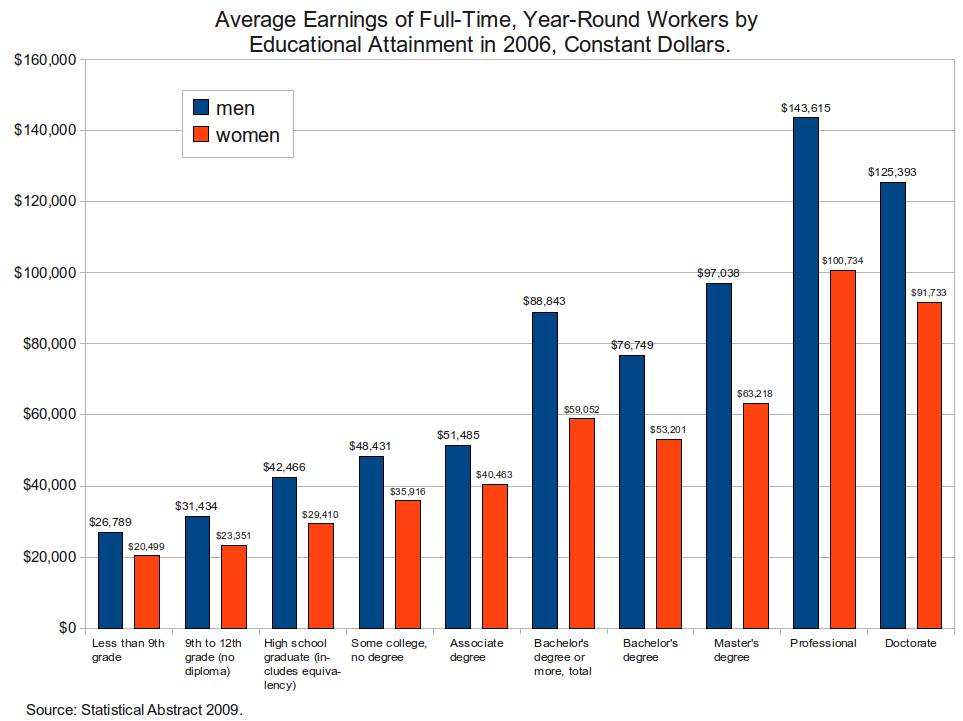

The cost of a four-year college education has risen roughly 150 percent since 1980. For this and other reasons, more and more students must take out student loans to finance their education. Upon graduation, many find they have accrued a sizable debt. Given the significant expense, some question the value of earning a college degree. However, along with the rising cost, the lifetime earnings difference between college and high school graduates has widened. The increased earnings potential for a bachelor’s degree allows a college graduate to recover the cost of college over time and eventually surpass the earnings of those with only a high school diploma.

For college to be a good investment, the benefits of a degree (e.g., higher pay) must outweigh the opportunity cost of attending. In this case, the opportunity cost is the sum of tuition and housing costs plus the wages that would have been earned from working directly after graduating from high school. Recent data show that while the cost of college increased, the labor-market value of a bachelor’s degree climbed to an all-time high. According to the College Board, recent college graduates who completely financed their education with student loans will earn enough by age 33 to cover the cost of those loans and match the to-date lifetime earnings of those the same age with only a high school diploma. Thus, the opportunity cost of attending college is recovered over time.

A college degree also lowers the probability of unemployment: From 1998 to 2011 the average unemployment rate for those with at least a bachelor’s degree was half that of those with only a high school diploma. Overall, a college degree still remains a wise investment.

Practicing Academic Integrity

I would prefer even to fail with honor than win by cheating. —Sophocles

At most educational institutions, “academic honesty” means demonstrating and upholding the highest integrity and honesty in all the academic work that you do. In short, it means doing your own work and not cheating, and not presenting the work of others as your own. The following are some common forms of academic dishonesty prohibited by most academic institutions:

Cheating

Cheating can take the form of crib notes, looking over someone’s shoulder during an exam, or any forbidden sharing of information between students regarding an exam or exercise. Many elaborate methods of cheating have been developed over the years—from hiding notes in the bathroom toilet tank to storing information in graphing calculators, pagers, cell phones, and other electronic devices. Cheating differs from most other forms of academic dishonesty, in that people can engage in it without benefiting themselves academically at all. For example, a student who illicitly telegraphed answers to a friend during a test would be cheating, even though the student’s own work is in no way affected.

Deception

Deception is providing false information to an instructor concerning an academic assignment. Examples of this include taking more time on a take-home test that is allowed, giving a dishonest excuse when asking for a deadline extension, or falsely claiming to have submitted work.

Fabrication

Fabrication is the falsification of data, information, or citations in an academic assignment. This includes making up citations to back up arguments or inventing quotations. Fabrication is most common in the natural sciences, where students sometimes falsify data to make experiments “work” or false claims are made about the research performed.

Plagiarism

Plagiarism, as defined in the 1995 Random House Compact Unabridged Dictionary, is the “use or close imitation of the language and thoughts of another author and the representation of them as one’s own original work.”[1] In an academic setting, it is seen as the adoption or reproduction of original intellectual creations (such as concepts, ideas, methods, pieces of information or expressions, etc.) of another author (whether an individual, group or organization) without proper acknowledgment. This can range from borrowing a particular phrase or sentence to paraphrasing someone else’s original idea without citing it. Today, in our networked digital world, the most common form of plagiarism is copying and pasting online material without crediting the source.

Common Forms of Plagiarism

According to “The Reality and Solution of College Plagiarism” created by the Health Informatics department of the University of Illinois at Chicago, there are ten main forms of plagiarism that students commit:

- Submitting someone else’s work as their own.

- Taking passages from their own previous work without adding citations.

- Rewriting someone’s work without properly citing sources.

- Using quotations, but not citing the source.

- Interweaving various sources together in the work without citing.

- Citing some, but not all passages that should be cited.

- Melding together cited and uncited sections of the piece.

- Providing proper citations, but failing to change the structure and wording of the borrowed ideas enough.

- Inaccurately citing the source.

- Relying too heavily on other people’s work. Failing to bring original thought into the text.

As a college student, you are now a member of a scholarly community that values other people’s ideas. In fact, you will routinely be asked to reference and discuss other people’s thoughts and writing in the course of producing your own work. That’s why it’s so important to understand what plagiarism is and the steps you can take to avoid it.

Avoiding Plagiarism

Below are some useful guidelines to help you avoid plagiarism and show academic honesty in your work:

- Quotes: If you quote another work directly in your work, cite your source.

- Paraphrase: If you put someone else’s idea into your own words, you still need to cite the author.

- Visual Materials: If you cite statistics, graphs, or charts from a study, cite the source. Keep in mind that if you didn’t do the original research, then you need to credit the person(s) or institution, etc. that did.

The easiest way to make sure you don’t accidentally plagiarize someone else’s work is by taking careful notes as you research. If you are doing research on the Web, be sure to copy and paste the links into your notes so can keep track of the sites you’re visiting. Be sure to list all the sources you consult.

Lastly, if you’re in doubt about whether something constitutes plagiarism, cite the source or leave the material out. Better still, ask for help. Most colleges have a writing center, a tutoring center, and a library where students can get help with their writing. Taking the time to seek advice is better than getting in trouble for not attributing your sources. Be honest about your ideas, and give credit where it’s due.

Consequences of Plagiarism

In the academic world, plagiarism by students is usually considered a very serious offense that can result in punishments such as a failing grade on the particular assignment, the entire course, or even being expelled from the institution. Individual instructors and courses may have their own policies regarding academic honesty and plagiarism; statements of these can usually be found in the course syllabus or online course description.

Course Delivery Formats

Choices. And more choices. If college success is about anything, it’s about the choices you need to make in order to succeed. What do you want to learn? How do you want to learn it? Who do you want to learn it with and where? When do you learn best?

As part of the many choices you will make in college, you will often be able to select the format in which your college classes are offered. The list below illustrates some of the main formats you may choose. Some formats lend themselves more readily to certain subjects. Others are based on how instructors believe the content can most effectively be delivered. Knowing a bit about your options can help you select your best environments for learning.

Lecture

Lecture-style courses are likely the most common course format, at least historically. In lecture courses, the professor’s main goal is to share a large amount of information, ideas, principles, and/or resources. Lecture-style courses often include discussions and other interactions with your fellow students.

Tip: Students can best succeed in this environment with dedicated study habits, time-management skills, note-taking skills, reading skills, and active listening skills. If you have questions, be sure to ask them during class. Meet with your instructor during office hours to get help on what you don’t understand, and ensure that you’re prepared for exams or other graded projects.

Laboratory

Lab courses take place in a controlled environment with specialized equipment, typically in a special facility. Students participating in labs can expect to engage fully with the material—to learn by doing. In a lab, you get first-hand experience in developing, practicing, translating, testing, and applying principles.

Tip: To best succeed as a student in a lab course, be sure to find out in advance what the course goals are, and make sure they fit your needs as a student. Expect to practice and master precise technical skills, like using a microscope or measuring a chemical reaction. Be comfortable with working as part of a team of fellow students. Enjoy the personal touches that are inherent in lab format courses.

Seminar

Seminar-style courses are geared toward a small group of students who have achieved an advanced level of knowledge or skill in a certain area or subject. In a seminar, you will likely do a good deal of reading, writing, and discussing. You might also conduct original research. You will invariably explore a topic in great depth. The course may involve a final project such as a presentation, term paper, or demonstration.

Tip: To best succeed in a seminar-style course, you must be prepared to participate actively, which includes listening actively. You will need to be well prepared, too. As a seminar class size is ordinarily small, it will be important to feel comfortable in relating to fellow students; mutual respect is key. Initiative and responsiveness are also vital.

Studio

Studio-style courses, similar to seminars, are also very active, but an emphasis is placed mainly on developing concrete skills, such as fine arts or theater arts. Studio courses generally require you to use specific materials, instruments, equipment, and/or tools. Your course may culminate in a public display or performance.

Tip: To succeed in a studio-style course, you need good time-management skills, because you will likely put in more time than in a standard class. Coming to class is critical, as is being well prepared. You can expect your instructors to help you start on projects and to provide you with resources, but much of your work will be self-paced. Your fellow students will be additional learning resources.

Workshop

Workshop-style courses are generally short in length but intensive in scope and interaction. Workshops generally have a lower student-to-teacher ratio than other courses. Often the goal of a workshop is the acquisition of information and/or skills that you can immediately apply.

Tip: To succeed as a learner in a workshop, you will need to apply yourself and participate fully for a limited time. A workshop may last a shorter amount of time than a full term.

Independent Study

Independent Study courses may be less common than other course formats. They allow you to pursue special interests not met in your formal curriculum and often involve working closely with a particular faculty person or adviser. Independent studies usually involve significant reading and writing and often end in a research project or paper. Your special, perhaps unique, area of interest will be studied thoroughly.

Tip: To succeed in an independent-study course, be prepared to work independently but cooperatively with an adviser or faculty member. Adopt high standards for your work, as you can plan for the possibility that your project or culminating research will be of interest to a prospective employer. Assume full responsibility for your learning outcomes, and be sure to pick a topic that deeply interests you.

Study Abroad

Study-abroad courses and programs give students opportunities to learn certain subjects in a country other than their own. For most U.S. students, a typical time frame for studying abroad is one or two academic terms. For many students, study-abroad experiences are life-changing.

Tip: To succeed in studying abroad, it may be most important to communicate openly before, during, and after your experience. Learn as much about the culture in advance as possible. Keep up with studies, but take advantage of opportunities to socialize. Use social networking to connect with others who have traveled where you plan to go.

Technology-Enhanced Formats

Most, if not all, college course formats can be delivered with technology enhancements. For example, lecture-style courses are often delivered fully online, and lab courses often have Web enhancements. Online teaching and learning are commonplace at most colleges and universities. In fact, the most recent data (2012) about the number of students taking online courses shows that roughly one out of every three U.S. college students take at least one online course.

Technology-enhanced delivery methods may be synchronous (meaning in real-time, through some kind of live interaction tool) as well as asynchronous (meaning in delayed time; they may include online discussion boards that students visit at different times within a certain time frame).

The following table describes the attributes of four main “modes” of delivery relative to the technology enhancements involved.

| CONTENT DELIVERED ONLINE | FORMAT | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|

| 0% | Face-to-Face / Traditional | A face-to-face course is delivered fully on-site with real-time, face-to-face interaction between the instructor and student. A face-to-face course may make use of computers, the Internet, or other electronic media in the classroom, but it does not use the institution’s learning management system for instruction. A learning management system, like Blackboard, Moodle, Canvas, or others, is an online teaching and learning environment that allows students and teachers to engage with one another and with course content. |

| 1% to 29% | Web-Enhanced | A Web-enhanced course takes place primarily in a traditional, face-to-face classroom, with some course materials being accessible online (generally in the learning management system), like digital readings to support learning objectives. All Web-enhanced classes regularly meet face-to-face. |

| 30% to 79% | Hybrid/ Blended | Hybrid courses (also called blended courses) strategically blend online and face-to-face delivery. “Flipped classrooms” are an example of hybrid delivery. In a flipped classroom, your instructor reverses the traditional order of in-class and out-of-class activity, such that you may be asked to view lectures at home before coming to class. You may then be asked to use class time for activities that enable you to engage dynamically with your instructor and fellow students. Blended courses have fewer in-person sessions than face-to-face or Web-enhanced courses. |

| 80+% | Online | An online course is delivered almost entirely through the institution’s learning management system or other online means, such as synchronous conferencing. Generally, very few or no on-site face-to-face class meetings are required. |

Online Courses

Most colleges now offer some online courses or regular courses with an online component. You experience an online course via a computer rather than a classroom. Many different variations exist, but all online courses share certain characteristics, such as working independently and communicating with the instructor (and sometimes other students) primarily through written computer messages.

Your online course may be Synchronous, which means it has scheduled virtual meeting times and attendance is usually required. Asynchronous means there are no live components to the class and all instruction is online. Asynchronous does not meet the class is self-paced; it will still have set due dates throughout the course. It is important to know the difference before registering. You should also find out what technology is required. Some classes require webcams for virtual meetings or proctored exams, some require you to have access to a printer, and almost all require that you have the ability to create, open, and edit word processing files.

- You need to own or have frequent access to a recent model of a computer with a high-speed, reliable Internet connection.

- For a synchronous section, without set class meeting times, you need to self-motivate to schedule your time to participate regularly.

- Without an instructor or other students in the room, you need to be able to pay attention effectively to the computer screen. Learning on a computer is not as simple as passively watching television! Take notes.

- Without reminders in class and peer pressure from other students, you’ll need to take responsibility to complete all assignments and papers on time.

- Since your instructor will evaluate you primarily through your writing, you need good writing skills for an online course. If you believe you need to improve your writing skills, put off taking an online course until you feel better prepared.

- You must take the initiative to ask questions if you don’t understand something.

- You may need to be creative to find other ways to interact with other students in the course. You could form a study group and get together regularly in person with other students in the same course.

Types of Classes in Your Degree Plan

Just as you have choices about the delivery format of your courses, you also have choices about where specific courses fit academically into your chosen degree program. For example, you can choose to take various combinations of required courses and elective courses in a given term. Typical college degree programs include both required and elective courses.

- A core course is a course required by your institution, and every student must take it in order to obtain a degree. It’s sometimes also called a general education course. Collectively, core courses are part of a core curriculum. Core courses are always essential to an academic degree, but they are not necessarily foundational to your major.

- A course required in your major, on the other hand, is essential to your specific field of study. For example, as an accounting student, you would probably have to take classes like organizational theory and principles of marketing. Your academic adviser can help you learn which courses within your major are required.

- An elective course, in contrast to both core courses and required courses in your major, is a variable component of your curriculum. You choose your electives from a number of optional subjects. Elective courses tend to be more specialized than required courses. They may also have fewer students than required courses.

Most educational programs prefer that students take a combination of elective and required courses during the same term. This is a good way to meet the demands of your program and take interesting courses outside your focus area at the same time. Since your required courses will be clearly specified, you may not have any questions about which ones to take or when to take them. But since you get to choose which elective courses you take, some interesting questions may arise.

It’s important to track and plan your required and elective courses from the outset. Take advantage of meeting with your adviser to help you make sure you are on the best trajectory to graduation. Reassess your plan as needed.

Who Are You As a Student?

Imagine for a moment that you live in the ancient city of Athens, Greece. You are a student at Plato’s University of Athens, considered in modern times to be the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. The campus sits just outside Athens’s city walls, a mile from your home. You walk to class and take your seat in the gymnasium, where all classes are held. Gatherings are small, just a handful of fellow students, most of whom are males born and raised in Athens. When your class is finished, you walk back to the city. Your daily work awaits you—hurry.

Now return to the present time. How does your college environment compare to the university in ancient Athens? Where do you live now, relative to campus? Do you report to a job site before or after class? Who are your fellow students, and where do they live in relationship to you and campus? What city or country are they from?

University life in America entails a diversity of the student body. Clearly, there is no “one size fits all” description of a college student. However, each student bears a responsibility to understand the diverse terrain of his or her peers. Who are the students you may share class with? How have they come to share the college experience with you? In this section, we look at several main categories of students and at some of the needs of students in those categories. We also take a brief look at how all students, regardless of background, can make a plan to be successful in college.

Traditional Students

Traditional undergraduate students typically enroll in college immediately after graduating from high school, and they attend classes on a continuous full-time basis at least during the fall and spring semesters (or fall, winter, and spring quarters). They complete a bachelor’s degree program in four or five years by the age of twenty-two or twenty-three. Traditional students are also typically financially dependent on others (such as their parents), do not have children, and consider their college career to be their primary responsibility. They may be employed only on a part-time basis, if at all, during the academic year.

Nontraditional Students

Nontraditional students do not enter college in the same calendar year that they finish high school. They typically attend classes part-time due to full-time work obligations. They are more likely to be financially independent, to have children, and/or to be caregivers of sick or elderly family members. Some nontraditional students may not have a high school diploma, or they may have received a general educational development degree (GED).

International Students and/or Non-native Speakers of English

International students are those who travel to a country different from their own for the purpose of studying in college. English is likely their second language. Non-native speakers of English, like international students, come from a different culture, too. For both of these groups, college may pose special challenges. For example, classes may at first, or for a time, pose hardships due to cultural and language barriers.

First-Generation College Students

First-generation students do not have a parent who graduated from college with a baccalaureate degree. College life may be less familiar to them, and the preparation for entering college may not have been stressed as a priority at home. Some time and support may be needed to become accustomed to the college environment. These students may experience a culture shift between school life and home life.

Students with Disabilities

Students with disabilities include those who have attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders, blindness or low vision, brain injuries, deafness/hard-of-hearing, learning disabilities, medical disabilities, physical disabilities, psychiatric disabilities, and speech and language disabilities. Students with disabilities are legally accorded reasonable accommodations that give them an equal opportunity to attain the same level of performance as students without a disability. Even with these accommodations, however, physical and electronic campus facilities and practices can pose special challenges. Time, energy, and added resources may be needed.

Veterans and Military Affiliated Students

This population is expected to increase as more veterans complete their service and seek higher education opportunities. Colleges play a large role in the transition veterans make when they return to civilian life and also benefit from veterans’ presence on their campuses.

While all students experience challenges when transitioning to college, veterans have unique challenges. As students, they have to interact with a civilian population and be responsible for their daily activities without having a direct chain of command to follow. Being a veteran also has its advantages. The skills and abilities that veterans bring to college can be an asset in many ways. Their service experience may make them more self-sufficient than other students, and their leadership skills are invaluable inside and outside the classroom. Veterans shared experiences lend a unique perspective that can enhance the learning experience for all students. The following is a list of characteristics that may apply to veteran students.

- Many veterans are older and may be more mature than traditional college-age students.

- Some veterans have more responsibilities, such as married life, children, and continuing military duties compared to traditional college-age students.

- Some veterans have seen overseas combat, but not all veteran students have been in combat situations or have been overseas.

- Some veterans have experienced war, death, horror, shock, fear, etc., and some may still be experiencing the physical and/or mental after-effects of deployment.

- Veterans are, in general, very motivated and self-disciplined students, and can contribute to the classroom and campus life.

Working Students

Many students are employed in either a part-time or full-time capacity. Balancing college life with work-life may be a challenge. Time management skills and good organization can help. These students typically have two jobs—being a student and an employee. It can be a lot to balance.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- College can bring great benefits such as increased income and lower unemployment but comes with the risk of time and money.

- Understanding and practicing Academic Integrity is a crucial component of college success.

- There are several different types of course delivery formats in college including lectures, labs, seminars, and independent study.

- Many classes use technology to enhance the classroom experience, are taught solely online, or are a hybrid of classroom and online instruction.

- There are different types of classes, including those required for your degree plan such as core courses and major required courses as well as electives.

- There are many different kinds of college students and you will experience a diverse environment in college.

LICENSES AND ATTRIBUTIONS

CC LICENSED CONTENT, ORIGINAL

- Manage the Transition to College. Authored by: Heather Syrett. Provided by: Austin Community College. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SHARED PREVIOUSLY

- San Jacinto EDUC 1300 – Types of Students. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/sanjacinto-learningframework/chapter/types-of-students/. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- San Jacinto EDUC 1300 – College Overview. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/sanjacinto-learningframework/chapter/college-overview/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- San Jacinto EDUC 1300 – Academic Honesty. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/sanjacinto-learningframework/chapter/academic-honesty/. License: CC BY: Attribution

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SPECIFIC ATTRIBUTION

- Is a College Cap and Gown a Financial Ball and Chain? August 2011. Authored by: Lowell R. Ricketts, Research Associate. Provided by: Prepared by the Economic Education Group of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Located at: https://files.stlouisfed.org/files/htdocs/pageone-economics/uploads/newsletter/2011/Lib0811ClassrmEdition.pdf. License: CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

- Northern Illinois University Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. (2012). Veterans in the classroom. In Instructional guide for university faculty and teaching assistants. Retrieved from http://www.niu.edu/citl/resources/guide/instructional-guide

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED CONTENT

PUBLIC DOMAIN CONTENT

-

- Gender Pay Gap Graph. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gender_pay_gap_in_the_United_States#/media/File:Average_earnings_of_workers_by_education_and_sex_-_2006.png. License: CC BY: Attribution