Writing is one of the key skills all successful students must acquire. You might think your main job in a history class is to learn facts about events. So you read your textbook and take notes on important dates, names, causes, and so on. But however important these details are to your instructor, they don’t mean much if you can’t explain them in writing. Even if you remember the facts well and believe you understand their meaning completely, if you can’t express your understanding by communicating it—in college that almost always means in writing—then as far as others may know, you don’t have an understanding at all. In a way, then, learning history is learning to write about history. Think about it. Great historians don’t just know facts and ideas. Great historians use their writing skills to share their facts and ideas effectively with others.

History is just one example. Consider a lab course—a class that’s as much hands-on as any in college. At some point, you’ll be asked to write a step-by-step report on an experiment you have run. The quality of your lab work will not show if you cannot describe that work and state your findings well in writing. Even though many instructors in courses other than English classes may not comment directly on your writing, their judgment of your understanding will still be mostly based on what you write. This means that in all your courses, not just your English courses, instructors expect good writing.

In college courses, writing is how ideas are exchanged, from scholars to students and from students back to scholars. While the grade in some courses may be based mostly on class participation, oral reports, or multiple-choice exams, writing is by far the single most important form of instruction and assessment. Instructors expect you to learn by writing, and they will grade you on the basis of your writing.

By paying attention to your writing and learning and practicing basic skills, even those who never thought of themselves as good writers can succeed in college writing. As with other college skills, getting off to a good start is mostly a matter of being motivated and developing a confident attitude that you can do it.

Research shows that deliberate practice—that is, close focus on improving one’s skills—makes all the difference in how one performs. Revisiting the craft of writing—especially early in college—will improve your writing much more than simply producing page after page in the same old way. Becoming an excellent communicator will save you a lot of time and hassle in your studies, advance your career, and promote better relationships and a higher quality of life off the job. Honing your writing is a good use of your scarce time.

Also, consider this: a recent survey of employers conducted by the Association of American Colleges and Universities found that 89 percent of employers say that colleges and universities should place more emphasis on “the ability to effectively communicate orally and in writing.” It was the single-most favored skill in this survey. In addition, several of the other valued skills are grounded in written communication: “Critical thinking and analytical reasoning skills” (81 percent); “The ability to analyze and solve complex problems” (75 percent); and “The ability to locate, organize, and evaluate information from multiple sources” (68 percent). This emphasis on communication probably reflects the changing reality of work in the professions. Employers also reported that employees will have to “take on more responsibilities,” “use a broader set of skills,” “work harder to coordinate with other departments,” face “more complex” challenges, and mobilize “higher levels of learning and knowledge.”

If you want to be a professional who interacts frequently with others, you have to be someone who can anticipate and solve complex problems and coordinate your work with others, all of which depend on effective communication.

The pay-off for improving your writing comes much sooner than graduation. Suppose you complete about 40 classes for a 120-credit bachelor’s’ degree, and—averaging across writing-intensive and non-writing-intensive courses—you produce about 2,500 words of formal writing per class. Even with that low estimate, you’ll write 100,000 words during your college career. That’s roughly equivalent to a 330-page book.

Spending a few hours sharpening your writing skills will make those 100,000 words much easier and more rewarding to write. All of your professors care about good writing.

It’s Different From High School

By the end of high school, you probably mastered many of the key conventions of standard academic English, such as paragraphing, sentence-level mechanics, and the use of thesis statements. The essay portion of the SAT measures important skills such as organizing evidence within paragraphs that relate to a clear, consistent thesis, and choosing words and sentence structures to effectively convey your meaning. These practices are foundational, and your teachers have given you a wonderful gift in helping you master them. However, college writing assignments require you to apply those skills to new intellectual challenges. Professors assign papers because they want you to think rigorously and deeply about important questions in their fields.

Academic Writing refers to writing produced in a college environment. Often this is writing that responds to other writing—to the ideas or controversies that you’ll read about. While this definition sounds simple, academic writing may be very different from other types of writing you have done in the past. Often college students begin to understand what academic writing really means only after they receive negative feedback on their work. To become a strong writer in college, you need to achieve a clear sense of two things:

- The academic environment

- The kinds of writing you’ll be doing in that environment

Professors look at you as independent junior scholars and expect you to write as someone who has a genuine, driving interest in tackling a complex question. They envision you approaching an assignment without a preexisting thesis. They expect you to look deep into the evidence, consider several alternative explanations, and work out an original, insightful argument that you actually care about.

Common Writing Assignments

Writing assignments can be as varied as the instructors who assign them. Some assignments are explicit about what exactly you’ll need to do, in what order, and how it will be graded. Some assignments are very open-ended, leaving you to determine the best path toward answering the project. Most fall somewhere in the middle, containing details about some aspects but leaving other assumptions unstated. It’s important to remember that your first resource for getting clarification about an assignment is your instructor—she or he will be very willing to talk out ideas with you, to be sure you’re prepared at each step to do well with the writing.

It would be simplistic to say that there are three, or four, or ten, or any number of types of academic writing that have unique characteristics, shapes, and styles. Every assignment in every course is unique in some ways, so don’t think of writing as a fixed form you need to learn. On the other hand, there are certain writing approaches that do involve different kinds of writing. An approach is a way you go about meeting the writing goals for the assignment. The approach is usually signaled by the words instructors use in their assignments.

When you first get a writing assignment, pay attention first to keywords for how to approach the writing. These will also suggest how you may structure and develop your paper. Look for terms like these in the assignment:

- Summarize. To restate in your own words the main point or points of another’s work.

- Define. To describe, explore, or characterize a keyword, idea, or phenomenon.

- Classify. To group individual items by their shared characteristics, separate from other groups of items.

- Compare/contrast. To explore significant likenesses and differences between two or more subjects.

- Analyze. To break something, a phenomenon, or an idea into its parts and explain how those parts fit or work together.

- Argue. To state a claim and support it with reasons and evidence.

- Synthesize. To pull together varied pieces or ideas from two or more sources.

Note how this list is similar to the words used in examination questions that involve writing. This overlap is not a coincidence—essay exams are an abbreviated form of academic writing such as a class paper.

Sometimes the keywords listed don’t actually appear in the written assignment, but they are usually implied by the questions given in the assignment. “What,” “why,” and “how” are common question words that require a certain kind of response. Look back at the keywords listed and think about which approaches relate to “what,” “why,” and “how” questions.

- “What” questions usually prompt the writing of summaries, definitions, classifications, and sometimes compare-and-contrast essays. For example, “What does Jones see as the main elements of Huey Long’s populist appeal?” or “What happened when you heated the chemical solution?”

- “Why” and “how” questions typically prompt analysis, argument, and synthesis essays. For example, “Why did Huey Long’s brand of populism gain force so quickly?” or “Why did the solution respond the way it did to heat?”

Successful academic writing starts with recognizing what the instructor is requesting, or what you are required to do. So pay close attention to the assignment. Sometimes the essential information about an assignment is conveyed through class discussions, however, so be sure to listen for the keywords that will help you understand what the instructor expects. If you feel the assignment does not give you a sense of direction, seek clarification. Ask questions that will lead to helpful answers. For example, here’s a short and very vague assignment:

Discuss the perspectives on religion of Rousseau, Bentham, and Marx. Papers should be four to five pages in length.

Faced with an assignment like this, you could ask about the scope or focus of the assignment:

- Which of the assigned readings should I concentrate on?

- Should I read other works by these authors that haven’t been assigned in class?

- Should I do research to see what scholars think about the way these philosophers view religion?

- Do you want me to pay equal attention to each of the three philosophers?

You can also ask about the approach the instructor would like you to take. You can use the keywords the instructor may not have used in the assignment:

- Should I just summarize the positions of these three thinkers, or should I compare and contrast their views?

- Do you want me to argue a specific point about the way these philosophers approach religion?

- Would it be okay if I classified the ways these philosophers think about religion?

Never just complain about a vague assignment. It is fine to ask questions like these. Such questions will likely engage your instructor in a productive discussion with you.

Summary Assignments

Being asked to summarize a source is a common task in many types of writing. It can also seem like a straightforward task: simply restate, in shorter form, what the source says. A lot of advanced skills are hidden in this seemingly simple assignment, however.

An effective summary does the following:

- Reflects your accurate understanding of a source’s thesis or purpose.

- Differentiates between major and minor ideas in a source.

- Demonstrates your ability to identify key phrases to quote.

- Demonstrates your ability to effectively paraphrase most of the source’s ideas.

- Captures the tone, style, and distinguishing features of a source.

- Does not reflect your personal opinion about the source.

That last point is often the most challenging: we are opinionated creatures, by nature, and it can be very difficult to keep our opinions from creeping into a summary, which is meant to be completely neutral.

In college-level writing, assignments that are only summary are rare. That said, many types of writing tasks contain at least some element of summary, from a biology report that explains what happened during a chemical process, to an analysis essay that requires you to explain what several prominent positions about gun control are, as a component of comparing them against one another.

Defined-Topic Assignments

Many writing tasks will ask you to address a particular topic or a narrow set of topic options. Even with the topic identified, however, it can sometimes be difficult to determine what aspects of the writing will be most important when it comes to grading.

Often, the handout or other written text explaining the assignment—what professors call the assignment prompt—will explain the purpose of the assignment, the required parameters (length, number, and type of sources, referencing style, etc.), and the criteria for evaluation. Sometimes, though—especially when you are new to a field—you will encounter the baffling situation in which you comprehend every single sentence in the prompt but still have absolutely no idea how to approach the assignment. No one is doing anything wrong in a situation like that. It just means that further discussion of the assignment is in order. Below are some tips:

- Focus on the verbs. Look for verbs like compare, explain, justify, reflect, or the all-purpose analyze. You’re not just producing a paper as an artifact; you’re conveying, in written communication, some intellectual work you have done. So the question is, what kind of thinking are you supposed to do to deepen your learning?

- Put the assignment in context. Many professors think in terms of assignment sequences. For example, a social science professor may ask you to write about a controversial issue three times: first, arguing for one side of the debate; second, arguing for another; and finally, from a more comprehensive and nuanced perspective, incorporating text produced in the first two assignments. A sequence like that is designed to help you think through a complex issue. If the assignment isn’t part of a sequence, think about where it falls in the span of the course (early, midterm, or toward the end), and how it relates to readings and other assignments. For example, if you see that a paper comes at the end of a three-week unit on the role of the Internet in organizational behavior, then your professor likely wants you to synthesize that material in your own way.

- Try a free-write. A free-write is when you just write, without stopping, for a set period of time. That doesn’t sound very “free”; it actually sounds kind of coerced, right? The “free” part is what you write—it can be whatever comes to mind. Professional writers use free-writing to get started on a challenging (or distasteful) writing task or to overcome writer’s block or a powerful urge to procrastinate. The idea is that if you just make yourself write, you can’t help but produce some kind of useful nugget. Thus, even if the first eight sentences of your free write are all variations on “I don’t understand this” or “I’d really rather be doing something else,” eventually you’ll write something like “I guess the main point of this is . . . ,” and suddenly you have the basis for your paper.

- Ask for clarification. Even the most carefully crafted assignments may need some verbal clarification, especially if you’re new to a course or field. Try to convey to your instructor that you want to learn and you’re ready to work, and not just looking for advice on how to get an A.

Although the topic may be defined, you can’t just grind out four or five pages of discussion, explanation, or analysis. It may seem strange, but even when you’re asked to “show how” or “illustrate,” you’re still being asked to make an argument. You must shape and focus that discussion or analysis so that it supports a claim that you discovered and formulated and that all of your discussion and explanation develops and supports.

Defined-topic writing assignments are used primarily to identify your familiarity with the subject matter.

Undefined-Topic Assignments

Another writing assignment you’ll potentially encounter is one in which the topic may be only broadly identified (“water conservation” in an ecology course, for instance, or “the Dust Bowl” in a U.S. History course), or even completely open (“compose an argumentative research essay on a subject of your choice”).

Where defined-topic essays demonstrate your knowledge of the content, undefined-topic assignments are used to demonstrate your skills—your ability to perform academic research, to synthesize ideas, and to apply the various stages of the writing process.

The first hurdle with this type of task is to find a focus that interests you. Don’t just pick something you feel will be “easy to write about”—that almost always turns out to be a false assumption. Instead, you’ll get the most value out of, and find it easier to work on, a topic that intrigues you personally in some way.

The same getting-started ideas described for defined-topic assignments will help with these kinds of projects, too. You can also try talking with your instructor or a writing tutor (at your college’s writing center) to help brainstorm ideas and make sure you’re on track. You want to feel confident that you’ve got a clear idea of what it means to be successful in the writing and not waste time working in a direction that won’t be fruitful.

What Do Instructors Really Want?

Some instructors may say they have no particular expectations for student papers. This is partly true. College instructors do not usually have one right answer in mind or one right approach to take when they assign a paper topic. They expect you to engage in critical thinking and decide for yourself what you are saying and how to say it. But in other ways, college instructors do have expectations, and it is important to understand them. Some expectations involve mastering the material or demonstrating critical thinking. Other expectations involve specific writing skills. Most college instructors expect certain characteristics in student writing. Here are general principles you should follow when writing essays or student “papers.” (Some may not be appropriate for specific formats such as lab reports.)

Title the paper to identify your topic. This may sound obvious, but it needs to be said. Some students think of a paper as an exercise and write something like “Assignment 2: History 101” on the title page. Such a title gives no idea about how you are approaching the assignment or your topic. Your title should prepare your reader for what your paper is about or what you will argue. (With essays, always consider your reader as an educated adult interested in your topic. An essay is not a letter written to your instructor.) Compare the following:

Incorrect: Assignment 2: History 101

Correct: Why the New World Was Not “New”

It is obvious which of these two titles begins to prepare your reader for the paper itself. Similarly, don’t make your title the same as the title of a work you are writing about. Instead, be sure your title signals an aspect of the work you are focusing on:

Incorrect: Catcher in the Rye

Correct: Family Relationships in Catcher in the Rye

Address the terms of the assignment. Again, pay particular attention to words in the assignment that signal a preferred approach. If the instructor asks you to “argue” a point, be sure to make a statement that actually expresses your idea about the topic. Then follow that statement with your reasons and evidence in support of the statement. Look for any signals that will help you focus or limit your approach. Since no paper can cover everything about a complex topic, what is it that your instructor wants you to cover?

Finally, pay attention to the little things. For example, if the assignment specifies “5 to 6 pages in length,” write a five- to six-page paper. Don’t try to stretch a short paper longer by enlarging the font (12 points is standard) or making your margins bigger than the normal one inch (or as specified by the instructor). If the assignment is due at the beginning of class on Monday, have it ready then or before. Do not assume you can negotiate a revised due date.

In your introduction, define your topic and establish your approach or sense of purpose. Think of your introduction as an extension of your title. Instructors (like all readers) appreciate feeling oriented by a clear opening. They appreciate knowing that you have a purpose for your topic—that you have a reason for writing the paper. If they feel they’ve just been dropped into the middle of a paper, they may miss important ideas. They may not make connections you want them to make.

Build from a thesis or a clearly stated sense of purpose. Many college assignments require you to make some form of an argument. To do that, you generally start with a statement that needs to be supported and build from there. Your thesis is that statement; it is a guiding assertion for the paper. Be clear in your own mind of the difference between your topic and your thesis. The topic is what your paper is about; the thesis is what you argue about the topic. Some assignments do not require an explicit argument and thesis, but even then you should make clear at the beginning your main emphasis, your purpose, or your most important idea.

Develop ideas patiently. You might, like many students, worry about boring your reader with too much detail or information. But college instructors will not be bored by carefully explained ideas, well-selected examples, and relevant details. College instructors, after all, are professionally devoted to their subjects. If your sociology instructor asks you to write about youth crime in rural areas, you can be sure he or she is interested in that subject.

In some respects, how you develop your paper is the most crucial part of the assignment. You’ll win the day with detailed explanations and well-presented evidence—not big generalizations. For example, anyone can write something broad (and bland) like “The constitutional separation of church and state is a good thing for America”—but what do you really mean by that? Specifically? Are you talking about banning “Christmas trees” from government property—or calling them “holiday trees” instead? Are you arguing for eliminating the tax-free status of religious organizations? Are you saying that American laws should never be based on moral values? The more you really dig into your topic—the more time you spend thinking about the specifics of what you really want to argue and developing specific examples and reasons for your argument—the more developed your paper will be. It will also be much more interesting to your instructor as the reader. Remember, those grand generalizations we all like to make (“America is the land of the free”) actually don’t mean much at all until we develop the idea in specifics. (Free to do what? No laws? No restrictions like speed limits? Freedom not to pay any taxes? Free food for all? What do you really mean when you say American is the land of the “free”?)

Integrate—do not just “plug in”—quotations, graphs, and illustrations. As you outline or sketch out your material, you will think things like “this quotation can go here” or “I can put that graph there.” Remember that a quotation, graph, or illustration does not make a point for you. You make the point first and then use such material to help back it up. Using a quotation, a graph, or an illustration involves more than simply sticking it into the paper. Always lead into such material. Make sure the reader understands why you are using it and how it fits in at that place in your paper.

Build clear transitions at the beginning of every paragraph to link from one idea to another. A good paper is more than a list of good ideas. It should also show how the ideas fit together. As you write the first sentence of any paragraph, have a clear sense of what the prior paragraph was about. Think of the first sentence in any paragraph as a kind of bridge for the reader from what came before.

Document your sources appropriately. If your paper involves research of any kind, indicate clearly the use you make of outside sources. If you have used those sources well, there is no reason to hide them. Careful research and the thoughtful application of the ideas and evidence of others is part of what college instructors value. (We address specifics about documentation later on.)

Carefully edit your paper. College instructors assume you will take the time to edit and proofread your essay. A misspelled word or an incomplete sentence may signal a lack of concern on your part. It may not seem fair to make a harsh judgment about your seriousness based on little errors, but in all writing, impressions count. Since it is often hard to find small errors in our own writing, always print out a draft well before you need to turn it in. Ask a classmate or a friend to review it and mark any word or sentence that seems “off” in any way. Although you should certainly use a spell-checker, don’t assume it can catch everything. A spell-checker cannot tell if you have the right word. For example, these words are commonly misused or mixed up:

- there, their, they’re

- its, it’s

- effect, affect

- complement, compliment

Your spell-checker can’t help with these. You also can’t trust what a “grammar checker” (like the one built into the Microsoft Word spell-checker) tells you—computers are still a long way from being able to fix your writing for you!

Turn in a clean hard copy. Some instructors accept or even prefer digital papers, but do not assume this. Most instructors want a paper copy and most definitely do not want to do the printing themselves. Present your paper in a professional (and unfussy) way, using a staple or paper clip on the left top to hold the pages together (unless the instructor specifies otherwise). Never bring your paper to class and ask the instructor, “Do you have a stapler?” Similarly, do not put your paper in a plastic binder unless the instructor asks you to.

tHE WRITING PROCESS

No writer, not even a professional, composes a perfect draft in her first attempt. Every writer fumbles and has to work through a series of steps to arrive at a high-quality finished project.

You may have encountered these steps as assignments in classes—draft a thesis statement, complete an outline, turn in a rough draft, participate in a peer review. The further you get into higher education, the less often these steps will be completed as part of a class.

That’s not to say that you won’t still need to follow these steps on your own time. It helps to recognize that these steps, commonly referred to as the writing process, aren’t rigid and prescribed. Instead, it can be liberating to see them as flexible, allowing you to adapt them to your own personal habits, preferences, and the topic at hand. You will probably find that your process changes, depending on the type of writing you’re doing and your comfort level with the subject matter.

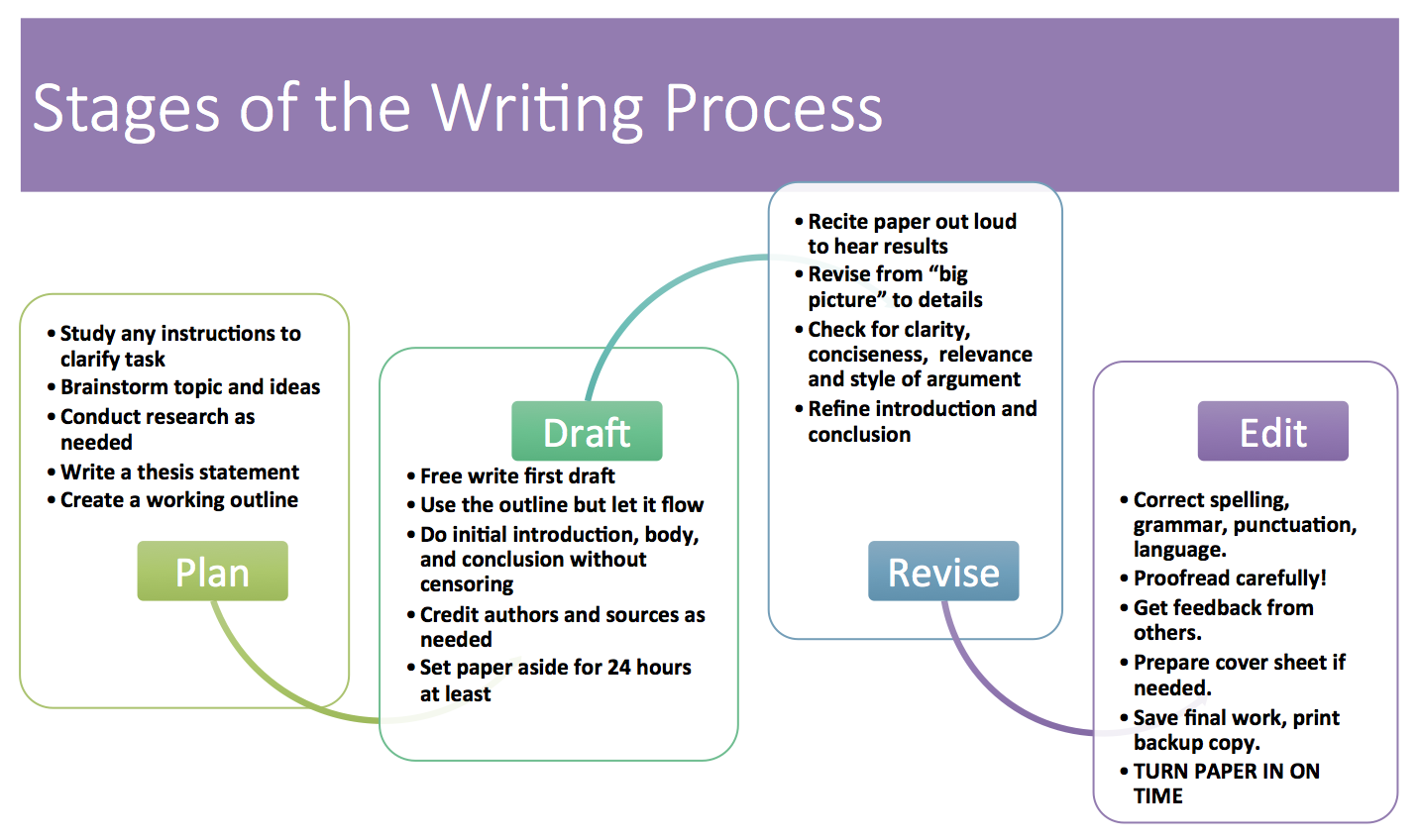

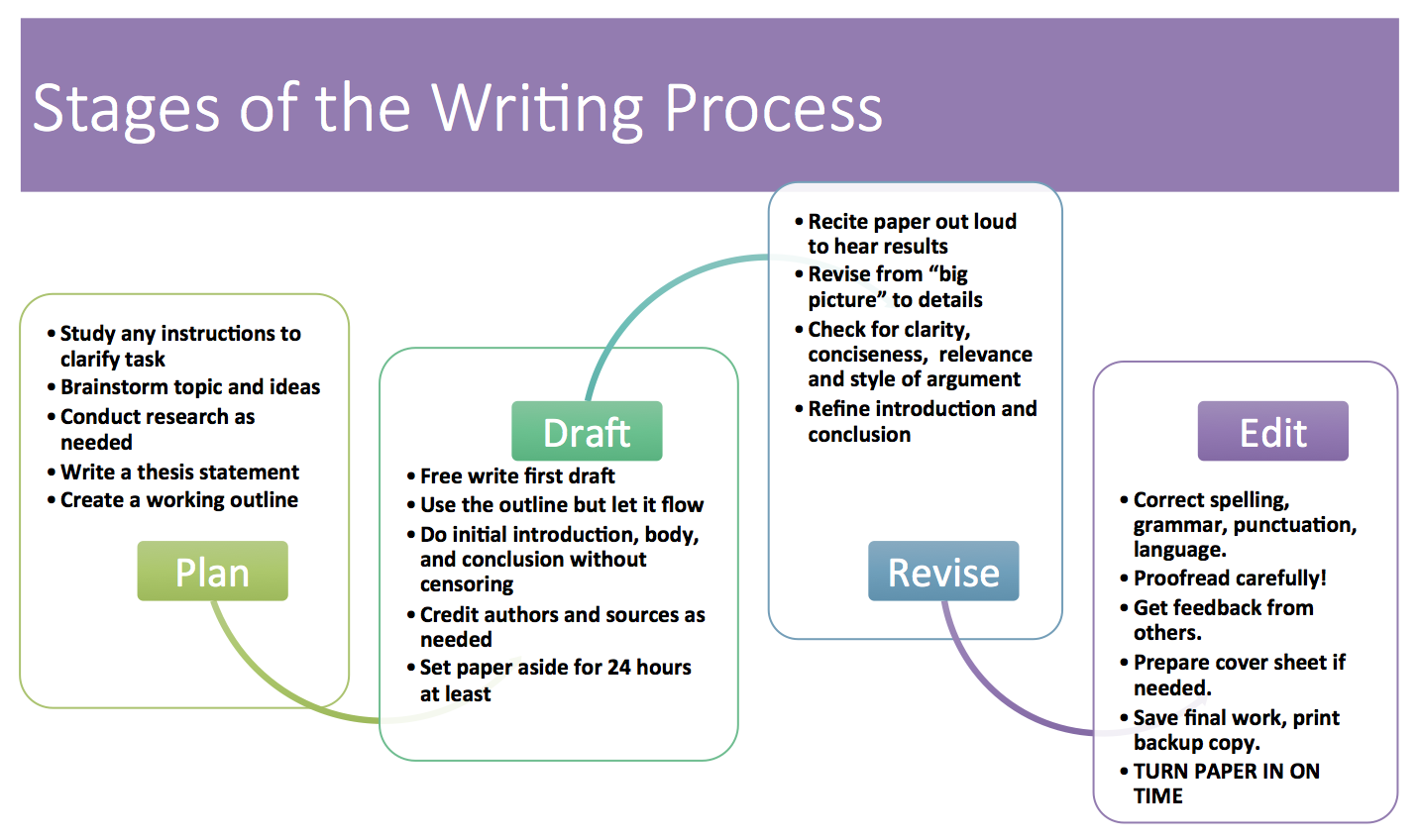

Consider the following flowchart of the writing process:

The writing process can be summed up in four steps: planning, drafting, revising and editing (proofreading.) The flowchart is a helpful visualization of the steps involved, outside of the classroom, toward completing an essay. Keep in mind that it isn’t always a linear process, though. It’s okay to loop back to earlier steps again if needed. For instance, after completing a draft, you may realize that a significant aspect of the topic is missing, which sends you back to researching. Or the process of research may lead you to an unexpected subtopic, which shifts your focus and leads you to revise your thesis. Embrace the circular path that writing often takes!

Involved in these four stages are a number of separate tasks—and that’s where you need to figure out what works best for you.

Because writing is hard, procrastination is easy. One good approach is to schedule shorter time periods over a series of days—rather than trying to sit down for one long period to accomplish a lot. (Even professional writers can write only so much at a time.) Try the following strategies to get started:

- Discuss what you read, see, and hear. Talking with others about your ideas is a good way to begin to achieve clarity. Listening to others helps you understand what points need special attention. A discussion also helps writers realize that their own ideas are often best presented in relation to the ideas of others.

- Use e-mail to carry on discussions in writing. An e-mail exchange with a classmate or your instructor might be the first step toward putting words on a page.

- Brainstorm. Jot down your thoughts as they come to mind. Just write away, not worrying at first about how those ideas fit together. (This is often called “free writing.”) Once you’ve written a number of notes or short blocks of sentences, pause and read them over. Take note of anything that stands out as particularly important to you. Also, consider how parts of your scattered notes might eventually fit together or how they might end up in a sequence in the paper you’ll get to later on.

- Keep a journal in which you respond to your assigned readings. Set aside twenty minutes or so three times a week to summarize important texts. Go beyond just summarizing: talk back about what you have been reading or apply the reading to your own experience. See Chapter 12 for more tips on taking notes about your readings.

- Ask and respond in writing to “what,” “why,” and “how” questions. Good questions prompt productive writing sessions. Again, “what” questions will lead to descriptions or summaries; “why” and “how” questions will lead you to analyses and explanations. Construct your own “what,” “why,” and “how” questions and then start answering them.

- In your notes, respond directly to what others have written or said about a topic you are interested in. Most academic writing engages the ideas of others. Academic writing carries on a conversation among people interested in the field. By thinking of how your ideas relate to those of others, you can clarify your sense of purpose and sometimes even discover a way to write your introduction.

All of these steps and actions so far are part of the planning stage. Again, almost no one just sits down and starts writing a paper at the beginning—at least not a successful paper! These prewriting steps help you get going in the right direction toward writing your draft. Once you are ready to start drafting your essay, keep moving forward in these ways:

- Write a short statement of intent or outline your paper before your first draft. Such a roadmap can be very useful, but don’t assume you’ll always be able to stick with your first plan. Once you start writing, you may discover a need for changes in the substance or order of things in your essay. Such discoveries don’t mean you made “mistakes” in the outline. They simply mean you are involved in a process that cannot be completely scripted in advance.

- Write down on a card or a separate sheet of paper what you see as your paper’s main point or thesis. As you draft your essay, look back at that thesis statement. Are you staying on track? Or are you discovering that you need to change your main point or thesis? From time to time, check the development of your ideas against what you started out saying you would do. Revise as needed and move forward.

- Reverse outline your paper. Outlining is usually a beginning point, a roadmap for the task ahead. But many writers find that outlining what they have already written in a draft helps them see more clearly how their ideas fit or do not fit together. Outlining in this way can reveal trouble spots that are harder to see in a full draft. Once you see those trouble spots, an effective revision becomes possible.

- Don’t obsess over detail when writing the draft. Remember, you have time for revising and editing later on. Now is the time to test out the plan you’ve made and see how your ideas develop. The last things in the world you want to worry about now are the little things like grammar and punctuation—spend your time developing your material, knowing you can fix the details later.

- Read your draft aloud. Hearing your own writing often helps you see it more plainly. A gap or an inconsistency in an argument that you simply do not see in a silent reading becomes evident when you give voice to the text. You may also catch sentence-level mistakes by reading your paper aloud.

What’s the Difference Between Revision and Editing?

These last two stages of the writing process are often confused with each other, but they mean very different things and serve very different purposes.

Revision is literally “re-seeing.” It asks a writer to step away from a piece of work for a significant amount of time and return later to see it with new eyes. This is why the process of producing multiple drafts of an essay is so important. It allows some space in between, to let thoughts mature, connections to arise, and gaps in content or an argument to appear. It’s also difficult to do, especially given that most college students face tight timelines to get big writing projects done. Still, there are some tricks to help you “re-see” a piece of writing when you’re short on time, such as reading a paper backward, sentence by sentence, and reading your work aloud. Both are ways of reconceptualizing your own writing so you approach it from a fresh perspective. Whenever possible, though, build in at least a day or two to set a draft aside before returning to work on the final version.

Revising a draft usually involves significant changes including the following:

- Making organizational changes like the reordering of paragraphs (don’t forget that new transitions will be needed when you move paragraphs).

- Clarifying the thesis or adjustments between the thesis and supporting points that follow.

- Cutting material that is unnecessary or irrelevant.

- Adding new points to strengthen or clarify the presentation.

Editing and Proofreading are the last steps following revision. This is the point where spelling, grammar, punctuation, and formatting all take center stage.

Editing and proofreading are focused, late-stage activities for style and correctness. They are important final parts of the writing process, but they should not be confused with revision itself. Editing and proofreading a draft involve these steps:

- Careful spell-checking. This includes checking the spelling of names.

- Attention to sentence-level issues. Be especially attentive to sentence boundaries, subject-verb agreement, punctuation, and pronoun referents. You can also attend at this stage to matters of style.

A person can be the best writer in the world and still be a terrible proofreader. It’s okay not to memorize every rule out there, but know where to turn for help. Utilizing the grammar-check feature of your word processor is a good start, but it won’t solve every issue (and may even cause a few itself).

Finding a trusted person to help you edit is perfectly ethical, as long as that person offers you advice and doesn’t actually do any of the writing for you. Professional writers rely on outside readers for both the revision and editing process, and it’s a good practice for you to do so, too.

Remember to get started on a writing assignment early so that you complete the first draft well before the due date, allowing you needed time for genuine revision and careful editing.

Checklists for Revision and Editing

When you revise…

|

Check the assignment: does your paper do what it’s supposed to do? |

|

Check the title: does it clearly identify the overall topic or position? |

|

Check the introduction: does it set the stage and establish the purpose? |

|

Check each paragraph in the body: does each begin with a transition from the preceding? |

|

Check organization: does it make sense why each topic precedes or follows another? |

|

Check development: is each topic fully explained, detailed, supported, and exemplified? |

|

Check the conclusion: does it restate the thesis and pull key ideas together? |

When you edit…

|

Read the paper aloud, listening for flow and natural word style. |

|

Check for any lapses into slang, colloquialisms, or nonstandard English phrasing. |

|

Check sentence-level mechanics: grammar and punctuation (pay special attention to past writing problems). |

|

When everything seems done, run the spell-checker again and do a final proofread. |

|

Check physical layout and mechanics against instructor’s expectations: Title page? Font and margins? Endnotes? |

Getting Help with Writing

Writing is hard work. Most colleges provide resources that can help you from the early stages of an assignment through to the completion of an essay. Your first resource may be a writing class. Most students are encouraged or required to enroll in a writing class in their first term, and it’s a good idea for everyone. Use everything you learn there about drafting and revising in all your courses.

Most colleges have a tutoring service that focuses primarily on student writing. Look up and visit your tutoring center early in the term to learn what service is offered. Specifically, check the following:

- Do you have to register in advance for help? If so, is there a registration deadline?

- Are appointments required or encouraged, or can you just drop in?

- Are regular standing appointments with the same tutor encouraged?

- Are a limited number of sessions allowed per term?

- Are small group workshops offered in addition to individual appointments?

- Are specialists available for help with students who have learned English as a second language?

Three points about writing tutors are crucial:

- Writing tutors are there for all student writers—not just for weak or inexperienced writers. Writing in college is supposed to be a challenge. Some students make writing even harder by thinking that good writers work in isolation. But writing is a social act. A good paper should engage others.

- Tutors are not there for you to “correct” sentence-level problems or polish your finished draft. They will help you identify and understand sentence-level problems so that you can achieve greater control over your writing. But their more important goals often are to address larger concerns like the paper’s organization, the fullness of its development, and the clarity of its argument. So don’t make your first appointment the day before a paper is due, because you may need more time to revise after discussing the paper with a tutor.

- Tutors cannot help you if you do not do your part. Tutors respond only to what you say and write; they cannot enable you to magically jump past the thinking an assignment requires. So do some thinking about the assignment before your meeting and be sure to bring relevant materials with you. For example, bring the paper assignment. You might also bring the course syllabus and perhaps even the required textbook. Most importantly, bring any writing you’ve done in response to the assignment (an outline, a thesis statement, a draft, an introductory paragraph). If you want to get help from a tutor, you need to give the tutor something to work with.

Teaching assistants and instructors. In a large class, you may have both a course instructor and a teaching assistant (TA). Seek help from either or both as you draft your essay. Some instructors offer only limited help. They may not, for example, have time to respond to a complete draft of your essay. But even a brief response to a drafted introduction or to a question can be tremendously valuable. Remember that most TAs and instructors want to help you learn. View them along with tutors as part of a team that works with you to achieve academic success.

Writing websites and writing handbooks. Many writing websites and handbooks can help you along every step of the way, especially in the late stages of your work. You’ll find lessons on style as well as information about language conventions and “correctness.” Not only should you use the handbook your composition instructor assigns in a writing class, but you should not sell that book back at the end of the term. You will need it again for future writing. For more help, become familiar with a good website for student writers.

Avoid Plagiarism: Cite Your Sources

College courses offer a few opportunities for writing that won’t require using outside resources. Creative writing classes, applied lab classes, or field research classes will value what you create entirely from your own mind or from the work completed for the class. For most college writing, however, you will need to consult at least one outside source, and possibly more.

Plagiarism is the unacknowledged use of material from a source. At the most obvious level, plagiarism involves using someone else’s words and ideas as if they were your own. There’s not much to say about copying another person’s work: it’s cheating, pure and simple. But plagiarism is not always so simple. Notice that our definition of plagiarism involves “words and ideas.” Let’s break that down a little further.

Words. Copying the words of another is clearly wrong. If you use another’s words, those words must be in quotation marks, and you must tell your reader where those words came from. But it is not enough to make a few surface changes in wording. You can’t just change some words and call the material yours; close, extended paraphrase is not acceptable. For example, compare the two passages that follow. The first comes from Murder Most Foul, a book by Karen Halttunen on changing ideas about murder in nineteenth-century America; the second is a close paraphrase of the same passage:

The new murder narratives were overwhelmingly secular works, written by a diverse array of printers, hack writers, sentimental poets, lawyers, and even murderers themselves, who were displacing the clergy as the dominant interpreters of the crime.

The murder stories that were developing were almost always secular works that were written by many different sorts of people. Printers, hack writers, poets, attorneys, and sometimes even the criminals themselves were writing murder stories. They were the new interpreters of the crime, replacing religious leaders who had held that role before.

It is easy to see that the writer of the second version has closely followed the ideas and even echoed some words of the original. This is a serious form of plagiarism. Even if this writer were to acknowledge the author, there would still be a problem. To simply cite the source at the end would not excuse using so much of the original source.

Ideas. Ideas are also a form of intellectual property. Consider this third version of the previous passage:

At one time, religious leaders shaped the way the public thought about murder. But in nineteenth-century America, this changed. Society’s attitudes were influenced more and more by secular writers.

This version summarizes the original. That is, it states the main idea in compressed form in language that does not come from the original. But it could still be seen as plagiarism if the source is not cited. This example probably makes you wonder if you can write anything without citing a source. To help you sort out what ideas need to be cited and what not, think about these principles:

Common knowledge. There is no need to cite common knowledge. Common knowledge does not mean knowledge everyone has. It means knowledge that everyone can easily access. For example, most people do not know the date of George Washington’s death, but everyone can easily find that information. If the information or idea can be found in multiple sources and the information or idea remains constant from source to source, it can be considered common knowledge. This is one reason so much research is usually done for college writing—the more sources you read, the more easily you can sort out what is common knowledge: if you see an uncited idea in multiple sources, then you can feel secure that idea is common knowledge.

Distinct contributions. One does need to cite ideas that are distinct contributions. A distinct contribution need not be a discovery from the work of one person. It need only be an insight that is not commonly expressed (not found in multiple sources) and not universally agreed upon.

Disputable figures. Always remember that numbers are only as good as the sources they come from. If you use numbers like attendance figures, unemployment rates, or demographic profiles—or any statistics at all—always cite your source of those numbers. If your instructor does not know the source you used, you will not get much credit for the information you have collected.

Everything said previously about using sources applies to all forms of sources. Some students mistakenly believe that material from the Web, for example, need not be cited. Or that an idea from an instructor’s lecture is automatically common property. You must evaluate all sources in the same way and cite them as necessary.

Forms of CitationYou should generally check with your instructors about their preferred form of citation when you write papers for courses. No one standard is used in all academic papers. You can learn about the three major forms or styles used in most any college writing handbook and on many Web sites for college writers:

- The Modern Language Association (MLA) system of citation is widely used but is most commonly adopted in humanities courses, particularly literature courses.

- The American Psychological Association (APA) system of citation is most common in the social sciences.

- The Chicago Manual of Style is widely used but perhaps most commonly in history courses.

Many college departments have their own style guides, which may be based on one of the above. Your instructor should refer you to his or her preferred guide, but be sure to ask if you have not been given explicit direction.

Use the Library

Almost all colleges have a library with professional librarians. These librarians are there to help you with identifying and locating resources. They are also experts in citing sources and avoiding plagiarism.

Other Kinds Of College Writing

Everything about college writing so far in this chapter applies to most college writing assignments. Some particular situations, however, deserve special attention. These include writing in-class essays, group writing projects, and writing in an online course.

Writing In-Class Essays

You might well think the whole writing process goes out the window when you have to write an in-class essay. After all, you don’t have much time to spend on the essay. You certainly don’t have time for an extensive revision of a complete draft. You also don’t have the opportunity to seek feedback at any stage along the way. Nonetheless, the best writers of in-class essays bring as much of the writing process as they can into an essay exam situation. Follow these guidelines:

- Prepare for writing in class by making writing a regular part of your study routine. Students who write down their responses to readings throughout a term have a huge advantage over students who think they can study by just reading the material closely. Writing is a way to build better writing, as well as a great way to study and think about the course material. Don’t wait until the exam period to start writing about things you have been studying throughout the term.

- Read the exam prompt or assignment very carefully before you begin to respond. Note keywords in the exam prompt. For example, if the exam assignment asks for an argument, be sure to structure your essay as an argument. Also look for ways the instructor has limited the scope of your response. Focus on what is highlighted in the exam question itself. See Chapter 12 for more tips for exam writing.

- Jot notes and sketch out a list of key points you want to cover before you jump into writing. If you have time, you might even draft an opening paragraph on a piece of scratch paper before committing yourself to a particular response. Too often, students begin writing before they have thought about the whole task before them. When that happens, you might find that you can’t develop your ideas as fully or as coherently as you need to. Students who take the time to plan actually write longer in-class essays than those who begin writing their answers right after they have read the assignment. Take as much as a fourth of the total exam period to plan.

- Use a consistent approach for in-class exams. Students who begin in-class exams with a plan that they have used successfully in the past are better able to control the pressure of the in-class exam. Students who feel they need to discover a new approach for each exam are far more likely to panic and freeze.

- Keep track of the time. Some instructors signal the passing of time during the exam period but do not count on that help. While you shouldn’t compulsively check the time every minute or two, look at your watch now and then.

- Save a few minutes at the end of the session for quick review of what you’ve written and for making small changes you note as necessary.

A special issue in in-class exams concerns handwriting. Some instructors now allow students to write in-class exams on laptops, but the old-fashioned blue book is still the standard in many classes. For students used to writing on a keyboard, this can be a problem. Be sure you don’t let poor handwriting hurt you. Your instructor will have many exams to read. Be courteous. Write as clearly as you can.

Group Writing Projects

College instructors sometimes assign group writing projects. The terms of these assignments vary greatly. Sometimes the instructor specifies roles for each member of the group, but often it’s part of the group’s tasks to define everyone’s role. Follow these guidelines:

- Get off to an early start and meet regularly through the process.

- Sort out your roles as soon as you can. You might divide the work into sections and then meet to pull those sections together. But you might also think more in terms of the specific strengths and interests each of you brings to the project. For example, if one group member is an experienced researcher, that person might gather and annotate materials for the assignment. You might also assign tasks that relate to the stages of the writing process. For example, one person for one meeting might construct a series of questions or a list of points to be addressed, to start a discussion about possible directions for the first draft. Another student might take a first pass at shaping the group’s ideas in a rough draft. Remember that whatever you do, you cannot likely keep each person’s work separate from the work of others. There will be and probably should be significant overlap if you are to eventually pull together a successful project.

- Be a good team player. This is the most important point of all. If you are assigned a group project, you should want to be an active part of the group’s work. Never try to ride on the skills of others or let others do more than their fair share. Don’t let any lack of confidence you may feel as a writer keep you from doing your share. One of the great things about a group project is that you can learn from others. Another great thing is that you will learn more about your own strengths that others value.

- Complete a draft early so that you can collectively review, revise, and finally edit together.

Writing in Online Courses

Online instruction is becoming more and more common. All the principles discussed in this chapter apply also to online writing—and many aspects are even more important in an online course. In most online courses, almost everything depends on written communication. The discussion is generally written rather than spoken. Questions and clarifications take shape in writing. Feedback on assignments is given in writing. To succeed in online writing, apply the same writing process as fully and thoughtfully as with an essay or paper for any course.

- Writing in college is not limited to the kinds of assignments commonly required in high school English classes.

- Writers in college must pay close attention to the terms of an assignment.

- Writing is a process that involves a number of steps; the product will not be good if one does not allow time for the process.

- Seek feedback from classmates, tutors, and instructors during the writing process.

- Revision is not the same thing as editing.

- Words and ideas from sources must be documented in a form recommended by the instructor.

- Even in in-class essays, using an abbreviated writing process approach helps produce more successful writing.

- Group writing projects require careful coordination of roles and cooperative stages but can greatly help students learn how to improve their writing.

- Writing for an online course puts your writing skills to the ultimate test when almost everything your instructor knows about your learning must be demonstrated through your writing.

LICENSES AND ATTRIBUTIONS

CC LICENSED CONTENT, ORIGINAL

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SHARED PREVIOUSLY

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED CONTENT