5

After completing this chapter, you will be able to:

- Understand what liquidity means and why it matters in everyday personal finance decisions.

- Identify key types of liquid assets and accounts, including checking, savings, CDs, and money market options.

- Compare financial products using APY, nominal rates, and after-tax yield to make better savings decisions.

- Use digital banking tools to manage liquidity effectively while avoiding common risks and automation pitfalls.

- Apply financial ratios like the Emergency Fund Ratio, Current Ratio, and Quick Ratio to measure your short-term financial health.

5.1 Why Liquidity is Freedom

5.1.1 What Does “Liquidity” Really Mean?

Liquidity isn’t just a finance term—it’s personal. It’s that feeling of knowing you can pay rent, fix your car, or buy a plane ticket without panicking. Technically speaking, liquidity is how easily and quickly you can access your money without losing value—whether through penalties, delays, or market fluctuations.

Think of it like this: A $1,000 emergency fund in your checking account is fully liquid. That same $1,000 locked into a 5-year CD? Not so much. And $1,000 worth of Bitcoin? Liquid-ish—until the market dips 12% overnight.

Liquidity = financial breathing room. The more liquid your money is, the more control you have when life throws surprises.

5.1.2 Life Comes at You Fast: The Role of Liquid Assets

In the words of financial planners, “Stuff happens.” And when it does, what saves you isn’t a credit card or a cousin—it’s having liquid assets.

Examples of liquid assets:

-

- Cash

- Checking or savings account balances

- Money Market Accounts (MMAs)

- Short-term Certificates of Deposit (CDs)

- U.S. Treasury Bills (T-Bills)

- Money Market Mutual Funds

Assets like your car, house, or long-term investments (e.g., stocks, crypto, or retirement accounts) are illiquid. Selling them takes time—and possibly a financial hit.

5.1.3 Kevin’s Wake-Up Call: A Case Study

Kevin had always felt “comfortable” with his money. He had savings, investments, Airbnb income, and strong credit. But when he and his partner decided to purchase a new investment property, they ran into a problem: most of Kevin’s money was tied up in real estate and stocks.

He wasn’t broke—but he wasn’t liquid.

Suddenly, he needed to free up tens of thousands of dollars to cover the down payment, closing costs, and early renovation work. That meant selling stocks, draining cash reserves, and navigating timing delays between money coming in and going out.

What happened?

-

-

Kevin had solid wealth, but his cash wasn’t immediately accessible.

-

Even smart investments can’t always help when deadlines are tight.

-

Liquidity became a strategic tool, not just a backup plan.

-

Moral of the story:

Liquidity isn’t just for emergencies. It’s about having options when opportunity knocks—and being able to act without sacrificing long-term goals.

5.1.4 The Three Roles of Liquid Assets

According to Keown, liquid assets serve three critical functions in personal finance:

-

- Transaction needs: Everyday expenses (groceries, rent, bills).

- Precautionary needs: Unplanned events (car repairs, medical bills).

- Speculative needs: Quick investment opportunities (e.g., buying when prices drop).

Without liquidity, you’re either borrowing or liquidating long-term assets—both of which can be costly.

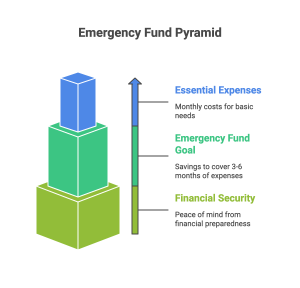

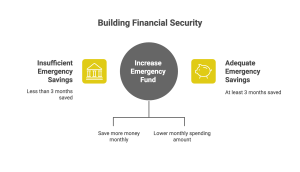

5.1.5 How Much Liquidity Do You Need?

Financial advisors often recommend keeping:

-

- 3 to 6 months of essential expenses in an emergency fund.

- Enough cash on hand to handle common unexpected costs.

A good rule of thumb is to start with $1,000 for basic emergencies, and gradually build up from there.

Marisol had just moved into her first apartment after college. She had a stable job, a tight budget, and a strong sense of independence. To “be responsible,” she transferred most of her savings into a mutual fund that promised long-term growth. But just three weeks later, her apartment’s plumbing burst, flooding her bedroom and damaging her laptop. The landlord covered the repair, but Marisol had to replace her computer out of pocket—and fast.

The problem?

Her money was invested, not liquid. She had to sell at a loss, wait five business days for the transfer to clear, and use a high-interest credit card in the meantime.

What did she learn?

Marisol realized that not all “smart” financial moves are smart in the short term. While investing can build wealth, it’s no substitute for having quick-access funds ready to go.

5.1.6 Final Thoughts

Liquidity isn’t just about having money—it’s about having access when you need it most. Emergencies don’t wait for the market to recover. Freedom comes from knowing your next move isn’t controlled by timing, penalties, or paperwork. The first step toward financial stability isn’t wealth. It’s liquidity.

5.2 Where to Keep Your Money

5.2.1 Not All Liquid Accounts Are Created Equal

Having cash is one thing. Knowing where to park it so it stays safe, accessible, and maybe even grows a little? That’s a whole different skill.

There are several options to hold your liquid assets. Some give you instant access but offer little to no interest. Others reward you with higher returns but tie your money up for a while. The trick is to understand what each account is designed for, what limitations come with it, and how to match it to your needs.

5.2.2 Common Cash Management Options

Checking accounts are the most flexible and accessible option. They are designed for everyday use—paying bills, withdrawing money, or using a debit card. While they rarely offer any interest, they are fully liquid and typically insured by the FDIC, making them very safe.

Savings accounts are better for storing emergency funds or short-term goals. They earn some interest (usually more than checking accounts), and they also offer FDIC protection. However, they often limit the number of withdrawals you can make each month.

Money Market Deposit Accounts (MMDAs) are a hybrid between savings and checking accounts. They usually require a higher minimum balance, offer better interest rates than regular savings accounts, and allow limited check-writing. They are insured and relatively safe but not as flexible as checking accounts.

Certificates of Deposit (CDs) offer higher interest in exchange for locking up your money for a set period—anywhere from three months to five years. Withdrawing early triggers a penalty. These accounts are not liquid but are ideal if you don’t need access to that cash for a while.

Treasury Bills (T-Bills) are short-term government securities. They are extremely safe and pay modest interest. However, they are not covered by FDIC insurance, and selling them before maturity may be complicated or come with a discount.

Money Market Mutual Funds (MMMFs) are offered by investment firms, not banks. They invest in short-term government or corporate securities and may offer higher returns than a savings account. But they are not federally insured and are subject to market risks.

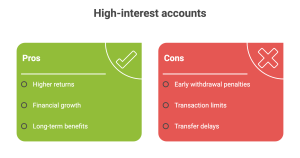

5.2.3 Read the Fine Print: Restrictions and Trade-Offs

Each of these tools has strings attached. CDs will penalize you if you withdraw your funds before the maturity date. MMDAs may limit your number of transactions. MMMFs are not backed by government insurance, and online banks may delay fund access by a few days.

The key is knowing how fast you may need your money and whether the trade-off in interest or restrictions fits your financial habits. If you’re someone who often dips into savings, having all your emergency money in a CD may not be the smartest move.

5.2.4 How Kevin Manages His Liquidity

Kevin doesn’t keep all his money in one place. Instead, he spreads his cash across different tools depending on how soon he might need it.

-

-

About 20% of his liquid assets are kept in a high-yield savings account—ready to cover short-term needs like unexpected repairs or a travel change.

-

Around 40% sits in short-term CDs or money market accounts, earning more interest but still accessible within a few months if needed.

-

The remaining 40% stays invested in stocks and ETFs, which offer long-term growth but aren’t ideal for emergencies or large upcoming expenses.

-

This layered approach allows Kevin’s money to work for him at different speeds:

-

-

Some is immediately available.

-

Some is growing steadily while still somewhat accessible.

-

Some is invested for the long term.

-

Lesson: Liquidity doesn’t mean everything sits in cash. It means building a plan so your money supports both your security and your goals.

Jordan had just started saving after getting her first full-time job. She opened a certificate of deposit (CD) offering 5% interest for 12 months and put her entire $4,000 savings into it. It felt smart—until life happened.

Two months later, her car broke down, and repairs cost $1,200. With no other savings, Jordan had to break the CD. The early withdrawal penalty cost her $150, and the process took four days, during which she had to borrow money from a coworker.

What went wrong?

Jordan focused on maximizing interest without considering liquidity. A better strategy might have been to keep $2,000 in a high-yield savings account for emergencies and only lock up the rest in a CD. That way, she could earn interest and stay flexible.

5.2.5 Final Thoughts

Where you keep your money matters just as much as how much you save. Liquidity gives you options, but it’s not all or nothing—you can mix flexibility and growth. The goal is to find the balance between earning interest and staying ready for life’s surprises. Cash isn’t just about security—it’s a tool for control.

5.3 Finding the Best Deal: Rates, Fees, and Taxes

5.3.1 The Hidden Cost of “Free” Accounts

Not all bank accounts are as “free” as they claim. You might see a savings account offering 3.00% interest and think, “Great deal!” But after taxes, inflation, and fees, your real return might be much lower—sometimes close to zero.

When comparing savings options, it’s not enough to look at the advertised rate. You need to consider three key factors:

-

- APY (Annual Percentage Yield) – This tells you the actual return you’ll earn in a year, including compounding.

- After-tax return – Some earnings are taxable, and that can reduce what you really keep.

- Fees and penalties – Monthly maintenance charges, minimum balance fees, or early withdrawal penalties can eat into your earnings fast.

In other words, the best deal isn’t always the one with the highest rate on paper.

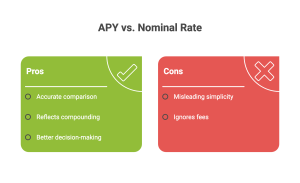

5.3.2 APY vs. Nominal Rate: What’s the Difference?

Let’s say a savings account advertises a 2.96% nominal interest rate, but it compounds daily. The APY—which factors in that daily compounding—might actually be 3.00%. That’s the number you want to use when comparing accounts.

If another bank offers 2.98% interest with only monthly compounding, the APY could be lower than the one with daily compounding, even if the nominal rate looks better.

That’s why APY is considered the real measure of what you’ll earn. It levels the playing field between different compounding methods.

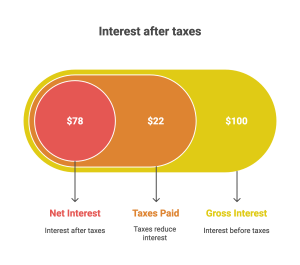

5.3.3 Taxes: The Silent Interest Killer

Let’s say you earn $100 in interest from a high-yield savings account. If you’re in the 22% tax bracket, you’ll pay $22 in federal taxes, leaving you with $78. This interest is taxed as ordinary income, so your tax bracket directly affects how much you keep.

Here’s a simple formula to estimate your after-tax return:

After-tax return = APY × (1 – tax rate)

So, if your APY is 4.00% and your tax rate is 22%, your real return would be 3.12%.

This matters most when comparing taxable accounts (like savings or CDs) with tax-advantaged options (like a Roth IRA or HSA, which can grow tax-free under certain conditions). While liquidity is limited in those, the tax benefits might justify it for longer-term savings.

5.3.4 Avoiding Fee Traps

Some accounts offer decent interest but come with rules that can catch you off guard:

-

- Minimum daily balance requirements

- Transaction limits

- Inactivity fees

- Monthly maintenance fees

Others use promotional interest rates that drop after a few months. Before opening an account, always read the fine print. Ask: What will this account actually cost or earn me over 12 months?

Many online banks offer higher APYs and fewer fees than traditional brick-and-mortar institutions—but they might take longer to transfer funds. Again, it’s about balancing yield with your need for access.

Case Study: Dante’s “High-Interest” Disappointment

Dante was excited to open a high-yield savings account offering 5.00% APY. He moved $10,000 into it and imagined his savings growing fast. But by the end of the year, his earnings were much lower than expected.

What happened?

- He didn’t maintain the $5,000 minimum balance during three months, which triggered $30 in fees.

- His interest earnings of $500 were taxed at 24%, reducing his gain to $380.

- He also forgot about a $10 monthly “service charge” after the promotional period ended.

In the end, his “5.00%” account earned him less than 2.50% in actual take-home interest.

Dante’s mistake wasn’t opening the account—it was assuming the headline rate was all that mattered.

5.3.5 Final Thoughts

Rates alone don’t tell the whole story. Fees, compounding, and taxes all affect how much your money really grows. Smart savers don’t chase numbers—they run the math. The best account is the one that fits your needs, respects your habits, and leaves your money working for you—not for the bank. Remember: A high headline rate means nothing if fees and taxes eat it up. Always check the real yield, not just the promo pitch.

5.4 Digital Money Management

5.4.1 Managing Money Without Setting Foot in a Branch

Not long ago, managing your cash meant driving to the bank, waiting in line, filling out forms, and carrying around paper receipts. Today, your entire financial life can live in your pocket.

Digital money management includes:

-

- Online banking platforms

- Mobile apps from banks and credit unions

- Independent fintech apps like Mint, YNAB (You Need A Budget), and Chime

- Peer-to-peer payment services like Venmo, Zelle, or Cash App

These tools allow you to track balances, transfer money, automate savings, pay bills, receive alerts, and even invest—all without visiting a branch.

5.4.2 The Benefits of Going Digital

There are clear advantages to using digital tools:

-

- Instant access to account balances and transactions

- Automation for savings, bills, and budgeting

- Spending insights to track where your money goes

- Mobile check deposit without needing an ATM

- Security alerts for unusual activity or low balances

Many apps use visuals, like pie charts and weekly summaries, to help you see patterns in your spending that are easy to miss with just bank statements.

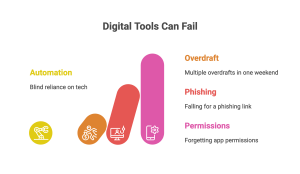

5.4.3 Risks and How to Avoid Them

While digital tools make managing your money easier, they come with some risks:

-

- Scams like phishing, where fake texts, emails, or websites trick you into sharing personal banking information

- Overreliance on connectivity, especially if your phone gets lost or stolen

- Data privacy concerns, especially with third-party apps that connect to your bank

To stay safe:

-

- Use two-factor authentication

- Only download apps from trusted sources

- Never share your PIN or password with anyone—even if they claim to be from your bank

- Review your bank permissions regularly and revoke access to apps you no longer use

Digital tools are powerful, but they require you to stay alert.

5.4.4 Kevin’s Tech Stack

Kevin manages his liquidity with a combination of tools:

-

- He uses a traditional bank for his checking account, mainly because it has a physical branch nearby.

- His savings are with an online bank offering a higher APY and zero fees.

- For budgeting, he uses Mint to track spending across his debit and credit cards.

- He has alerts set up for any transaction over $300, and automatic transfers scheduled on payday to separate his emergency fund from daily spending.

This setup gives him visibility, control, and structure—without needing to log into multiple platforms each day.

Dana loved her banking app. It sent colorful notifications, gave her cashback rewards, and even had an auto-save feature. But she didn’t realize the app was rounding up every debit card purchase and moving the difference into savings—even when her balance was low.

One weekend, her balance hit zero, but the app still auto-transferred $3.74. That triggered an overdraft fee. Then came a second fee when her Spotify subscription hit. Then a third, when her rent check bounced.

By Monday, Dana owed the bank $95—just because the app did what she told it to do.

She turned off the auto-save and learned a painful lesson: automation is helpful, but only if you’re watching the system.

5.4.5 Final Thoughts

Digital money tools can be life-changing—if used wisely. They make it easier to save, monitor, and act. But they’re not magic. No app can replace judgment, discipline, or financial awareness. Use technology as a partner, not a crutch. And always stay one step ahead of your money.

5.5 Ratios That Reveal Your Financial Health

5.5.1 Numbers That Actually Matter

When people talk about financial health, they often focus on credit scores or net worth. But those metrics don’t always reflect your day-to-day stability. That’s where liquidity ratios come in.

Liquidity ratios help you answer one basic question:

If something unexpected happened tomorrow, how prepared are you to handle it—without going into debt?

There are three simple but powerful ratios you can calculate using just a few numbers from your own finances. Think of them as your financial vital signs.

5.5.2 The Emergency Fund Ratio

This ratio shows how many months you could survive on your liquid assets if your income stopped suddenly.

Formula:

Emergency Fund Ratio = Total Liquid Assets ÷ Monthly Essential Expenses

Let’s say you have $6,000 in savings, and your basic monthly expenses (rent, groceries, insurance, etc.) are $2,000. Your ratio would be:

$6,000 ÷ $2,000 = 3.0 months

Most experts recommend keeping 3 to 6 months’ worth of expenses in liquid form. Less than that, and you’re exposed. More than that, and you might be missing out on higher returns elsewhere.

5.5.3 The Current Ratio

This ratio compares all your liquid assets to all your short-term liabilities. These include upcoming bills, minimum credit card payments, rent, or any other obligations due within the next 1–3 months.

It’s a quick way to assess whether you can meet your near-future obligations without borrowing.

Formula:

Current Ratio = Liquid Assets ÷ Short-Term Liabilities

If you have $4,500 in accessible funds and $3,000 due in the next three months (bills, credit cards, subscriptions), your ratio is:

$4,500 ÷ $3,000 = 1.5

A ratio above 1.0 is healthy. Below 1.0 means you owe more than you have ready to pay.

5.5.4 The Quick Ratio (Liquidity Ratio)

The quick ratio is a stricter version of the current ratio. It excludes any asset that might take more than a few days to access, like CDs or non-liquid investments.

Formula:

Quick Ratio = (Cash + Checking + Savings) ÷ Short-Term Liabilities

This ratio tells you how much “pure liquidity” you have to cover your immediate responsibilities.

Sofia always thought she was financially “okay.” Her checking account hovered around $1,200, she had a few thousand in a CD, and she paid her credit card off every few months.

But when her freelance income dried up, she ran the numbers.

- Emergency Fund Ratio: 1.5 months

- Current Ratio: 0.9

- Quick Ratio: 0.5

Her Emergency Fund Ratio showed she could only cover 1.5 months of expenses. Her Current Ratio showed she owed more than she had readily available. Her Quick Ratio—a stricter test—was even worse.

She realized most of her money was tied up in accounts she couldn’t access immediately. She had liquidity—but not usable liquidity. It was a wake-up call.

Sofia moved half of her CD into a money market account and set up a system to rebuild her emergency fund, one transfer at a time.

5.5.5 Final Thoughts

Ratios don’t lie. They help you see what your balance sheet alone can’t: readiness. Liquidity isn’t about having money—it’s about having the right money in the right place when life gets unpredictable. A good liquidity plan is like a seatbelt: you hope you never need it, but you’ll be thankful it’s there when you do.

5.6 Liquidity Ratios in Action

5.6.1 What Are Liquidity Ratios?

Liquidity ratios help you assess your short-term financial strength. Instead of just asking “How much money do I have?”, these ratios ask “How easily can I use that money when something comes up?”

They focus on:

-

-

Liquid assets (cash, checking, savings)

-

Near-liquid assets (CDs, money market accounts)

-

Short-term liabilities (credit card payments, rent, bills due soon)

-

5.6.2 Emergency Fund Ratio

Formula:

Emergency Fund Ratio = Total Liquid Assets ÷ Monthly Essential Expenses

This tells you how many months you could survive without income.

Example:

If you have $6,000 in checking and savings, and your monthly expenses are $2,000:

$6,000 ÷ $2,000 = 3 months

📌 Target: 3 to 6 months

If it’s below 3, you’re at risk in a job loss or emergency.

5.6.3 Current Ratio

Formula:

Current Ratio = (Liquid Assets + Near-Liquid Assets) ÷ Short-Term Liabilities

This measures your ability to meet your near-term obligations.

Example:

You have $2,000 in checking, $1,000 in savings, $3,000 in a CD. You owe $1,500 in bills.

($2,000 + $1,000 + $3,000) ÷ $1,500 = 4.0

📌 A ratio above 1 is safe; below 1 means you’re relying on credit.

5.6.4 Quick Ratio (or “Liquidity Ratio”)

Formula:

Quick Ratio = (Cash + Checking + Savings) ÷ Short-Term Liabilities

This is stricter—it excludes assets you can’t access quickly, like CDs.

Example:

($2,000 + $1,000) ÷ $1,500 = 2.0

📌 Shows how “ready” your money is in case of a financial surprise.

5.6.5 Use These Ratios to Adjust Your Plan

If your Emergency Fund Ratio is too low, it’s a sign to pause investing and build savings first.

If your Quick Ratio is weak but your Current Ratio is okay, consider moving money from illiquid accounts (like CDs) into more flexible options (like a high-yield savings account).

💡 These ratios are your financial dashboard. Check them every 3–6 months as your situation changes.

5.7 Early Withdrawal, CD Penalties & Real-World Savings Decisions

5.7.1 CD vs. Savings Account: Trade-Offs

-

-

Savings Account: Fully liquid. Low interest.

-

CD (Certificate of Deposit): Higher interest. Locked for a term. Early withdrawal = penalty.

-

Only put money in a CD if you won’t need it during the term.

5.7.2 CD Early Withdrawal Penalty

Common Penalty:

3 months of interest (sometimes 6 months, depending on the bank).

Formula:

Penalty = Annual Interest × (Months Penalty ÷ 12)

Example:

You invest $4,000 in a 12-month CD earning 5%.

Annual interest = $4,000 × 0.05 = $200

3-month penalty = $200 × (3 ÷ 12) = $50

5.7.3 Proportional Withdrawal from a CD

If you only need part of the CD (e.g., $1,000 from a $4,000 CD), calculate the penalty proportionally:

Formula:

Penalty = (Withdrawal ÷ Total CD) × Full Penalty

Example:

Withdraw $1,000 from a $4,000 CD with a $50 full penalty:

($1,000 ÷ $4,000) × $50 = $12.50

5.7.4 After-Tax Yield Comparison

To compare taxable accounts, use:

Formula:

After-Tax Return = APY × (1 – Tax Rate)

Example:

-

-

Option A: 4% APY, 24% tax rate → 4% × (1 – 0.24) = 3.04%

-

Option B: 5.25% APY, 24% tax rate → 5.25% × 0.76 = 3.99%

-

The second account earns more after taxes, even though both are taxable.

5.7.5 Building an Emergency Fund: Planning Backwards

Formula:

Goal = Monthly Expenses × Number of Months

Time to Save = (Goal – Current Savings) ÷ Monthly Contribution

Example:

You need 6 months of $2,000 expenses = $12,000

You already have $2,000

You save $500/month

Time to reach goal:

($12,000 – $2,000) ÷ $500 = 20 months

5.7.6 Final Thoughts

A good liquidity plan doesn’t just protect you—it gives you freedom to act. Whether it’s avoiding CD penalties or choosing the highest after-tax yield, the goal is the same:

Make sure your money is ready when you are.

- Liquidity gives you the ability to respond to unexpected expenses without going into debt or selling long-term investments.

- Not all savings tools are equally liquid—understanding the tradeoffs between access, return, and safety is essential.

- APY and after-tax yield are more accurate measures of earnings than just the advertised interest rate.

- Digital tools can simplify cash management, but only if you stay actively involved and protect your data.

- Personal liquidity ratios help you track how financially prepared you are to handle emergencies or income disruptions.

Conceptual Questions

- What is liquidity, and why is it important in personal finance?

- Describe the difference between a checking account and a savings account in terms of liquidity and return.

- What does APY stand for, and how is it different from a nominal interest rate?

- Why is it important to consider after-tax yield when comparing financial products?

- List and briefly explain three types of financial institutions that offer liquid asset accounts.

- What is the Emergency Fund Ratio, and what does it measure?

Scenario-Based Questions

Case Study 1:

Jordan earns $2,800 a month after taxes and currently has $3,500 in a checking account. He keeps no other savings.

- Calculate his Emergency Fund Ratio.

- Is he financially prepared for a job loss? Why or why not?

- What steps could Jordan take to improve his liquidity management?

Case Study 2:

Amira split her liquid assets across three products: $2,000 in a checking account, $2,500 in a savings account earning 3.50% APY, and $3,000 in a 12-month CD earning 5.00% interest.

- Which of Amira’s assets are fully liquid, and which are not?

- If she suddenly needs $4,000 for a medical emergency, what are her best options?

- What penalties or risks might she face if she withdraws from her CD early?

Case Study 3:

Leo uses a digital app that automatically rounds up his purchases and transfers the difference to a savings account. Last month, he overdrafted his account three times due to these automatic transfers.

- What is the potential downside of automated digital tools like this?

- How could Leo adjust his system to keep using automation without overdrafting?

- What role does liquidity play in avoiding these kinds of errors?

Problem-Solving & Financial Calculation Tasks

- You have $8,000 in liquid savings and monthly essential expenses of $2,000. Calculate your Emergency Fund Ratio. What would be a safe target ratio, and how much more would you need to save to reach it?

- Maria has $3,200 in a money market account and $1,000 in a CD. She owes $1,900 in short-term bills this month. Calculate her Current Ratio and Quick Ratio.

- Compare the after-tax yield of the following two options. Assume a 24% tax rate:

- Use: After-tax return = APY × (1 – tax rate).

- A savings account offering 4.00% APY

- A money market mutual fund offering 5.25% APY

Which one offers the better real return after taxes?

- Alan invests $5,000 in a CD that earns 5.5% interest annually. He withdraws the money after 9 months, paying a 3-month interest penalty. How much interest does he earn after the penalty?

- Create a liquidity plan for someone who earns $3,500 a month, wants to build a 4-month emergency fund, and is deciding how to split funds between a savings account and a CD.

- Using what you’ve learned, write a one-paragraph recommendation for a friend who wants to keep $10,000 safe but still earn interest—without risking access in an emergency.

-

List the key factors they should consider (e.g., safety, access, interest).

-

Then write the recommendation.

-