10

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Explain the core concepts of investing, including risk, return, diversification, and liquidity.

- Describe how stocks work, the main types of stocks, and how to evaluate stock investments.

- Identify the major types of bonds, how bond pricing and yields work, and the risks of bond investing.

- Compare mutual funds and ETFs, including index funds, actively managed funds, and target-date funds.

- Recognize the role of retirement accounts (401(k), IRA, Roth IRA) and the importance of starting early.

- Understand the basics of estate planning, including wills, trusts, and beneficiaries.

- Develop investment strategies for life events, including marriage, children, college, inheritance, and retirement, and explain why portfolio rebalancing matters.

10.1 Investment Basics

Investing can feel like a mysterious club reserved for Wall Street professionals in sharp suits, but here’s the truth: you don’t need to be a financial wizard to start investing. In fact, the earlier you begin, the easier it becomes to grow your money and reach your life goals—whether that’s retiring comfortably, buying a home, or just building enough wealth to sleep peacefully at night.

At its core, investing is about putting your money to work so that it grows over time. Instead of your dollars just sitting in a checking account, you allow them to “hire a job” in the form of stocks, bonds, mutual funds, or other assets. The return you get is the “salary” your money earns for working. But, like any job, there are risks involved—and that’s where learning the basics becomes essential.

In this section, we’ll cover four foundational concepts every investor must understand: risk, return, diversification, and liquidity. We’ll also introduce the major types of assets and show why investing early can make an enormous difference.

10.1.1 Key Terms You Must Know

Before diving into specific investments, let’s break down some words you’ll see over and over again.

Think of these four as the DNA of investing. If you understand them, everything else will make more sense.

10.1.2 The Relationship Between Risk and Return

Here’s the deal: higher risk usually equals higher potential return.

-

- A savings account has almost no risk, but it also pays you almost nothing in interest.

- Stocks can rise dramatically in value, but they can also lose money quickly.

- Bonds tend to sit in the middle, offering moderate risk and moderate returns.

This trade-off is called the risk-return relationship. Investors need to decide how much risk they’re willing to take based on their goals and time horizon.

A common myth among beginners is that investing is about finding a “safe” option with guaranteed high returns. Sorry—that unicorn doesn’t exist. Instead, smart investing is about balancing your personal tolerance for risk with your financial goals.

10.1.3 Types of Asset Classes

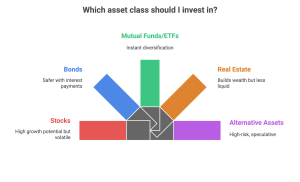

There are many ways to invest, but the most common asset classes include:

-

- Stocks (Equities): Ownership shares in a company. They can grow a lot in value but are volatile.

- Bonds: Loans you make to a company or government. They pay interest and are generally safer than stocks.

- Mutual Funds and ETFs: Investment “baskets” that hold dozens or hundreds of stocks or bonds, giving you instant diversification.

- Real Estate: Property you buy to rent out or sell later. Can build wealth but is less liquid and requires more management.

- Alternative Assets (Crypto, Commodities, etc.): High-risk, often speculative assets. Some people dabble, but they shouldn’t be the foundation of your portfolio.

For most new investors, the building blocks are stocks, bonds, and mutual funds/ETFs. We’ll cover each in detail later in this chapter.

10.1.4 Why Diversification Matters

Imagine you own stock in just one company. If that company suddenly collapses (think Enron, Lehman Brothers, or FTX), you could lose everything. But if you spread your investments across 100 companies, the odds of all of them going bankrupt are slim.

This is the power of diversification—your winners balance out your losers. Think of it as building a team: not everyone has to be a superstar, but as long as your lineup is solid overall, you’ll win more games than you lose.

10.1.5 Example: The Cost of Not Investing

Let’s compare two friends, Alex and Jordan.

-

- Alex saves $1,000 per year starting at age 20 and stops at 30 (10 years of investing). He leaves the money invested at an average return of 8%.

- Jordan waits until 30 to start investing and contributes $1,000 per year until age 65 (35 years of investing).

Who do you think ends up with more money at retirement?

Surprisingly, Alex comes out ahead—because starting early gave his money more time to compound. Even though Jordan invested much more overall, Alex’s head start shows the incredible effect of compound growth.

This is why financial advisors say: “The best time to start investing was yesterday. The second-best time is today.”

10.1.6 Case Studies

Maria is nervous about investing and decides to keep her $10,000 in a savings account earning just 0.5% interest. After 20 years, her balance grows to only about $11,000. Her friend David takes the same $10,000 and invests in a diversified stock index fund averaging 7% annually. After 20 years, his account grows to roughly $38,700.

Lesson: Avoiding risk may feel safe, but it can actually mean losing out on far greater long-term growth.

James is 25 and hears about a hot new cryptocurrency online. Convinced it’s his ticket to fast wealth, he puts his entire $5,000 savings into it. At first, the gamble seems brilliant—the coin’s value jumps, and James briefly sees his account climb to $8,000. Feeling confident, he ignores advice to diversify.

But within a year, the hype fades and the coin crashes, leaving James with only $1,000. Had he spread his money across stocks, bonds, and a small slice of crypto, the drop would have hurt less and most of his savings would still be intact.

Lesson: All-in bets can pay off briefly, but without diversification, one bad swing can wipe out years of savings.

10.1.7 Final Thought

-

- Risk and return are linked—no investment is “high return, no risk.”

- Diversification is your best defense against market volatility.

- Liquidity matters when you might need cash quickly.

- Time is your friend—the earlier you start, the more compounding works for you.

10.2 Investing in Stocks

When people think of investing, the first image that comes to mind is usually the stock market—shouting traders, tickers rolling across the screen, and the roller coaster of prices going up and down. Stocks can be intimidating, but they’re also one of the most powerful tools for building wealth. In fact, over the long term, stocks have outperformed nearly every other type of investment.

In this section, we’ll break down what stocks are, the different types you’ll encounter, how the stock market works, and the basics of evaluating stocks. By the end, you’ll see why millions of people use stocks to grow their money—and also why it’s important to approach them with both excitement and caution.

10.2.1 What Are Stocks?

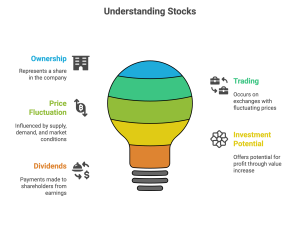

A stock (also called “equity”) is a share of ownership in a company. When you buy stock, you’re buying a piece of that business.

-

- If the company grows and earns profits, the value of your stock usually increases.

- If the company struggles or fails, your stock may decrease in value—or even become worthless.

Owning stock gives you two main potential benefits:

-

- Price appreciation – the value of the stock increases over time.

- Dividends – some companies share profits with shareholders by paying cash dividends.

Think of buying stock as joining a team. If the company wins, you share in the rewards. But if the team loses, you also share in the pain.

10.2.2 Types of Stocks

Stocks come in different flavors, and understanding them helps you choose the right ones for your portfolio.

-

- Common Stock: The most widely owned. Gives you voting rights at shareholder meetings and the chance to earn dividends and capital gains.

- Preferred Stock: Offers no voting rights but often pays higher, fixed dividends. It’s considered a mix between a stock and a bond.

Another way to classify stocks is by growth style:

-

- Growth Stocks: Companies expected to grow faster than the market average. Examples: Tesla, Amazon (in its early days). They usually reinvest profits rather than pay dividends. High potential reward, but high risk.

- Value Stocks: Stocks that are considered undervalued compared to their fundamentals (like earnings or assets). Example: established companies like Coca-Cola. Often pay steady dividends.

10.2.3 How the Stock Market Works

The stock market is simply a place where buyers and sellers trade shares of companies. But it’s not just one big marketplace—it’s made up of many exchanges.

-

- New York Stock Exchange (NYSE): The largest and most famous, home to companies like Disney and Coca-Cola.

- NASDAQ: Known for tech giants like Apple, Microsoft, and Google.

- Indexes: Collections of stocks used to track overall market performance. Examples include the S&P 500 (500 largest U.S. companies), Dow Jones Industrial Average (30 major companies), and NASDAQ Composite (mostly tech-focused).

Indexes act like a report card for the market. When you hear “the market was up today,” it usually refers to these indexes.

10.2.4 Evaluating Stocks

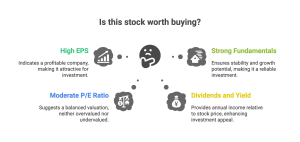

How do you know if a stock is worth buying? Analysts look at many factors, but here are a few beginner-friendly ones:

-

- Earnings Per Share (EPS): The company’s profit divided by the number of shares. Higher EPS generally means a more profitable company.

- Price-to-Earnings (P/E) Ratio: The stock’s price divided by its EPS. It tells you how much investors are willing to pay for $1 of earnings. A very high P/E can signal excitement—or overvaluation.

- Dividends and Yield: If a stock pays dividends, the yield shows how much you earn annually relative to the stock’s price.

- Company fundamentals: Revenue growth, debt levels, and industry position.

While these metrics are useful, remember: no formula guarantees success. Stock prices are influenced by countless factors, from company performance to investor psychology and global events.

10.2.5 Case Studies

Back in 1997, Apple was close to bankruptcy and many investors thought the company was finished. Buying its stock at that time looked risky, even foolish. But with the launch of the iPod, iPhone, and Mac innovations, Apple reinvented itself and became one of the most valuable companies in the world. A $1,000 investment in Apple stock in 2005 would be worth more than $50,000 today.

Lesson: Betting on innovative companies can take years to pay off, but patient long-term investors are often rewarded.

In 2021, GameStop and AMC became the center of an internet-fueled buying craze. Online communities pushed the prices up far beyond what the companies were worth on paper. Some early investors made quick fortunes, but many others jumped in late and lost big when the prices crashed back down.

Lesson: Stock prices don’t always match company value—hype and speculation can drive markets just as much as fundamentals.

10.2.6 Kevin’s Personal Experience

Kevin didn’t start actively investing in individual stocks until after finishing his MBA. Before that, he simply contributed to his retirement plan and selected whatever low-cost index fund was available. Once he began investing on his own, though, he was naturally drawn to tech stocks because of his career in Silicon Valley. He put money into big names like Apple and Microsoft, but also chased some “hot” startup picks that didn’t perform well.

While it wasn’t during the dot-com crash, Kevin still experienced the emotional rollercoaster of buying stocks based on excitement and hype. That experience taught him the importance of diversification—not just owning tech companies he admired, but building a more balanced portfolio. Today, his investments include companies like MercadoLibre, Costco, and Broadcom, and even a few stocks he admits he doesn’t fully understand. Ironically, some of those have turned out to be strong performers, reinforcing the value of staying diversified rather than overthinking every pick.

10.2.7 Tips for New Stock Investors

-

- Start with companies you know and understand.

- Don’t try to time the market—it’s nearly impossible.

- Use index funds or ETFs if choosing individual stocks feels overwhelming.

- Remember that stocks are long-term investments. Daily fluctuations are normal.

10.2.8 Final Thought

-

- Stocks represent ownership in a company, with potential profits through price increases and dividends.

- Common vs. preferred and growth vs. value are the main types of stocks.

- Stock markets and indexes track overall performance and provide benchmarks.

- Evaluating stocks involves looking at earnings, P/E ratios, dividends, and company fundamentals.

- Investing in stocks can lead to high rewards—but also carries high risks.

10.3 Investing in Bonds

When you hear the word “investing,” most people picture the stock market. But there’s another side to the investment world that’s just as important: bonds. Stocks are about owning a piece of a company, while bonds are about lending money—to companies, cities, or governments—in exchange for interest.

Bonds are often considered the “boring cousin” of stocks, but don’t let that reputation fool you. They play a critical role in any balanced portfolio by providing stability, steady income, and diversification. Let’s break down what bonds are, how they work, the different types, and the risks you need to know before investing in them.

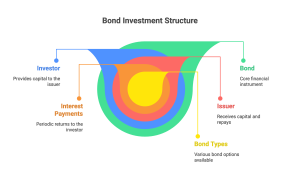

10.3.1 What Are Bonds?

A bond is essentially an IOU. When you buy a bond, you are loaning money to the bond issuer (a government, corporation, or municipality). In return, they promise to:

-

- Pay you interest at a fixed rate (called the coupon).

- Repay the original loan amount (called the principal or face value) when the bond matures.

For example, if you buy a $1,000 bond with a 5% annual coupon, you’ll receive $50 each year until the bond matures. At maturity, you get back your original $1,000.

This steady stream of payments is what makes bonds attractive to more conservative investors.

10.3.2 Types of Bonds

There are several main categories of bonds, each with different levels of risk and return:

-

- Treasury Bonds (T-Bonds): Issued by the U.S. government. They are considered the safest because the government backs them. Examples: 10-year Treasury note, 30-year Treasury bond.

- Municipal Bonds (Munis): Issued by states, cities, or local governments to fund public projects like schools or highways. Many are tax-exempt, making them especially attractive for high-income investors.

- Corporate Bonds: Issued by companies to raise money for expansion, acquisitions, or other projects. They generally offer higher yields than government bonds—but also higher risk.

- High-Yield (Junk) Bonds: Issued by companies with lower credit ratings. They pay higher interest to compensate for the greater risk of default.

10.3.3 Bond Pricing and Yields

Here’s where bonds can get a little tricky. Bonds don’t always trade at their face value. Their price changes depending on interest rates and market demand.

-

- If new bonds are paying 6% interest, but you hold an older bond paying only 4%, your bond is less attractive, so its price falls.

- If interest rates fall, your older bond paying 6% looks great, so its price rises.

This leads to an important concept:

-

- Yield to Maturity (YTM): The total return an investor can expect if they hold the bond until it matures. It considers both the coupon payments and any gain or loss if the bond was purchased at a discount or premium.

Think of yield as the “true earning rate” of the bond.

10.3.4 Risks of Bonds

Bonds are often safer than stocks, but they are not risk-free. Here are the main risks:

-

- Interest Rate Risk: When rates rise, bond prices fall.

- Default Risk: The issuer might fail to pay interest or repay principal (more common with junk bonds).

- Inflation Risk: Inflation erodes the real value of fixed interest payments.

- Liquidity Risk: Some bonds are harder to sell quickly without losing value.

- The takeaway: bonds reduce volatility, but you still need to choose wisely.

10.3.5 Case Studies

Jasmine invests $5,000 in U.S. Treasury bonds at 3% annual interest. Over 10 years, she earns steady payments and gets her $5,000 back at maturity. While her returns aren’t spectacular, she sleeps well knowing her money is safe.

Lesson: Treasury bonds are reliable but modest.

Marco wants higher returns than government bonds, so he invests $10,000 in corporate bonds from a retail company offering a 7% yield. At first, everything seems fine—he receives steady interest payments. But five years later, the company runs into financial trouble and defaults. Instead of getting his full investment back, Marco recovers only $7,000.

Lesson: Higher yields come with higher risk. Always check a company’s credit rating and financial health before buying its bonds.

10.3.6 Bonds in a Portfolio

Bonds are essential for diversification. In general:

-

- Younger investors may hold fewer bonds and more stocks since they can tolerate risk.

- Older investors may shift toward more bonds for stability and income.

A popular guideline is the “Rule of 110”: Subtract your age from 110 to estimate the percentage of your portfolio in stocks. The rest should be in bonds. For example, a 30-year-old might have 80% stocks and 30% bonds.

10.3.7 Final Thought

-

- Bonds are loans you make to governments or companies in exchange for interest.

- Treasury bonds are safest; corporate and junk bonds carry higher risk but pay more.

- Bond prices move inversely to interest rates.

- Risks include interest rate changes, default, inflation, and liquidity.

- Bonds add balance and stability to an investment portfolio.

10.4 Mutual Funds and ETFs

Not everyone wants to spend hours researching individual stocks or bonds. The good news? You don’t have to. That’s where mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs) come in. These investments let you buy a slice of a basket of assets instead of picking each one yourself. It’s like ordering a combo meal instead of building your burger ingredient by ingredient—it’s easier, balanced, and often cheaper in the long run.

10.4.1 How Mutual Funds Work

A mutual fund pools money from thousands (or even millions) of investors to buy a wide variety of stocks, bonds, or other securities.

-

- Managed by a professional fund manager (or a team).

- Each investor owns “shares” of the fund, which represent a slice of the overall portfolio.

- Returns come from dividends, interest, and capital gains.

One key detail: mutual funds are priced once per day (at the “net asset value” or NAV). You can only buy or sell at that daily price.

10.4.2 Types of Mutual Funds

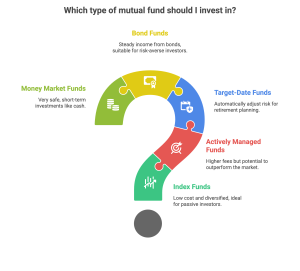

Mutual funds come in many varieties, but the most common are:

-

- Index Funds: Track a market index like the S&P 500. They’re low cost, diversified, and very popular.

- Actively Managed Funds: Try to “beat the market” by picking stocks and bonds. These charge higher fees.

- Target-Date Funds: Designed for retirement investing. They automatically shift from risky to safer assets as you approach a chosen retirement year.

- Bond Funds: Invest in government or corporate bonds for steady income.

- Money Market Funds: Very safe, short-term investments that act almost like cash.

10.4.3 Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs)

An ETF works like a mutual fund—it holds a basket of securities—but trades on the stock exchange like a stock. That means:

-

- Prices change throughout the day, just like individual stocks.

- You can buy and sell anytime during trading hours.

- Fees are typically very low, especially for index ETFs.

For example, buying one share of an S&P 500 ETF instantly gives you exposure to 500 of the largest U.S. companies. That’s instant diversification for the price of a single stock.

10.4.4 Mutual Funds vs. ETFs: The Showdown

Both mutual funds and ETFs make investing simple, but they have differences:

-

- Trading: Mutual funds are priced once per day; ETFs trade all day.

- Costs: ETFs usually have lower expense ratios.

- Management: Both can be passive (index-based) or active.

- Minimums: Mutual funds may require a few thousand dollars to start; ETFs can be bought with the price of one share.

Bottom line: ETFs tend to be cheaper and more flexible, while mutual funds are great for “set it and forget it” retirement accounts.

10.4.5 Why Diversification Is a Big Deal

By owning one mutual fund or ETF, you can instantly own hundreds—or even thousands—of securities. That’s diversification made simple.

-

- If one company in the fund does poorly, the impact is small.

- Funds also allow you to invest globally, across different industries and markets, without needing to research each one individually.

For small investors, this is one of the best ways to reduce risk without sacrificing growth potential.

10.4.6 Case Studies

Emily, at age 22, decides to invest $200 per month in an S&P 500 index fund. She sticks with the plan consistently, letting the money grow instead of trying to time the market. By age 65, assuming an average annual return of 8%, her account grows to over $700,000—even though she only contributed about $103,000 over the years.

Lesson: Index funds make it easy to stay invested. With patience and consistency, they turn small monthly contributions into long-term wealth.

Carlos and his twin brother Luis both start investing the same amount each month. Carlos chooses an actively managed mutual fund with annual fees of 1.5%, while Luis puts his money into a low-cost index ETF charging only 0.05%. Over 30 years, the difference in fees compounds dramatically. Even though they both invested in “mutual funds,” Luis ends up with tens of thousands more than Carlos—simply because he paid less in fees.

Lesson: Small percentage fees may not sound like much, but over time they can eat away huge chunks of your returns. Always check the expense ratio before investing.

10.4.7 Kevin’s Personal Experience

During his time working in Silicon Valley, Kevin was too busy to spend hours researching individual companies. Instead of trying to pick stocks, he chose a simpler and more efficient strategy: investing in low-cost mutual funds and ETFs. Over time, he noticed that broad index funds consistently performed better than many actively managed alternatives—and certainly better than relying on gut feelings.

When he began saving for his children’s future, Kevin picked a target-date retirement fund. It automatically adjusted its asset allocation as his kids got closer to college age. He appreciated the simplicity and automation.

His advice: “If you’re busy or new to investing, don’t overcomplicate it. Set up automatic contributions into a diversified fund and let time and compounding do the heavy lifting.”

10.4.8 Tips for Fund Investing

-

- Choose low-cost funds (expense ratios matter).

- For retirement accounts, consider target-date funds for simplicity.

- Use ETFs if you want flexibility and lower fees.

- Avoid chasing last year’s “top-performing” fund—it often doesn’t repeat.

10.4.9 Final Thought

-

- Mutual funds and ETFs let you invest in a basket of assets instead of picking individually.

- Index funds are low-cost, passive, and usually outperform most active funds in the long run.

- ETFs trade like stocks, while mutual funds trade once per day.

- Diversification is the key benefit: one fund can give you exposure to hundreds of companies.

- Watch out for high fees—they can significantly reduce your wealth over time.

10.5 Retirement & Estate Planning

Planning for retirement might feel like something only your grandparents need to worry about, but here’s the secret: the earlier you start, the easier it becomes. Thanks to the magic of compound growth, even small amounts of money invested when you’re young can snowball into a comfortable retirement.

But retirement planning isn’t just about saving money. It’s also about using the right investment accounts (like 401(k)s and IRAs), understanding tax advantages, and thinking ahead about what happens to your assets after you’re gone. That last piece is called estate planning—and though it sounds fancy, it simply means deciding who inherits your money and belongings and how to minimize taxes and stress for your loved ones.

This section will cover retirement accounts, the importance of starting early, and the basics of estate planning.

10.5.1 Retirement Accounts: Your Wealth-Building Toolbox

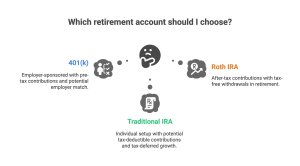

Different types of retirement accounts exist to help you grow your savings. They all share one goal: encourage people to save by offering tax benefits.

-

- 401(k): Offered by many employers. You contribute pre-tax dollars, which lowers your taxable income now. Money grows tax-deferred until retirement, when you pay taxes as you withdraw. Many employers also offer a match (free money—never leave it on the table!).

- Traditional IRA (Individual Retirement Account): Similar to a 401(k) but set up individually. Contributions may be tax-deductible, growth is tax-deferred, and withdrawals in retirement are taxed.

- Roth IRA: Contributions are made with after-tax money (you don’t get a tax break upfront), but the big win is that withdrawals in retirement are tax-free.

10.5.2 Why Starting Early Matters

Let’s look at two savers, Ashley and Ben.

-

- Ashley invests $200/month starting at age 22 and stops at 32. She never contributes again.

- Ben waits until 32 to start, then invests $200/month until age 65.

Who ends up with more at retirement?

Despite contributing for only 10 years, Ashley ends up with more—because her money had decades to compound. Ben invests three times as much, but time is the real superpower.

This is the magic of compound interest: money earning interest on top of interest. Starting early is the single most powerful decision you can make in your financial life.

10.5.3 Estate Planning Basics

Estate planning may not be on the top of your to-do list when you’re 20, but it’s smart to understand the basics:

-

- Will: A legal document stating who gets your assets when you pass away.

- Trust: A financial arrangement that allows a third party (the trustee) to manage your assets for beneficiaries. Can reduce estate taxes and avoid probate.

- Beneficiaries: The people or organizations you designate to receive your accounts (like retirement funds or life insurance).

- Power of Attorney & Health Directives: Legal documents giving someone authority to make financial or medical decisions if you’re unable.

Even a simple will and updated beneficiary designations can save your family time, stress, and money.

10.5.4 Case Studies

At age 20, Carla opens a Roth IRA and commits to investing just $100 per month. She keeps at it for 45 years, letting her contributions grow at an average annual return of 8%. By age 65, her account grows to more than $500,000—even though she only contributed about $54,000 in total.

Lesson: Starting small and early is incredibly powerful. Time and compound growth matter more than the size of your monthly contribution.

When Luis passes away unexpectedly, he leaves no will or estate plan. His family is forced into a long probate process, where the courts must decide how to divide his assets. The process takes years, racks up legal fees, and delays access to money his children urgently need. What could have been a smooth transfer turned into stress and financial hardship for his loved ones.

Lesson: Estate planning isn’t only for the wealthy—it’s about making sure your family is protected and supported without unnecessary costs or delays.

10.5.5 Kevin’s Personal Experience

Unlike many people his age, Kevin started thinking seriously about retirement the moment he entered the workforce. In his very first year of employment, he began maximizing contributions to his 401(k)—and later, as his income grew, he also contributed to a 457 plan and made annual backdoor Roth IRA contributions.

At one point, he was contributing across multiple accounts, maxing out every available retirement option—not just to build long-term savings, but also to reduce his tax liability while in a high tax bracket.

Eventually, as a parent, Kevin also took steps to protect his family’s financial future by setting up a living trust. This ensures that if anything were to happen to him, his children would be cared for without legal delays or complications.

His takeaway:

“Retirement accounts aren’t just about the distant future. They’re one of the most powerful tools to reduce taxes and build security. Estate planning isn’t about you—it’s about protecting the people you love.”

10.5.6 Tips for Students and Young Adults

-

- If your employer offers a 401(k) match, contribute at least enough to get the full match—it’s free money.

- Open a Roth IRA if you can—it’s ideal for young people in lower tax brackets.

- Don’t wait. Even $25/month invested in your 20s beats $200/month starting in your 40s.

- Update your beneficiaries whenever you have major life changes (marriage, kids, divorce).

10.5.7 Final Thought

-

- Retirement accounts (401(k), IRA, Roth IRA) grow your wealth with tax advantages.

- Starting early maximizes compound growth—even small contributions matter.

- Estate planning ensures your assets go where you want and avoids costly delays for your family.

- Both retirement and estate planning are acts of self-care and love for your future self and your loved ones.

10.6 Investment Strategies for Life Events

Investing isn’t just about building wealth in the abstract. It’s about preparing for the real-life events that shape our futures: getting married, buying a home, raising kids, paying for college, or leaving an inheritance. Each life stage brings different priorities, risks, and opportunities. A smart investor adapts their strategy to fit their circumstances—because your financial goals at 22 are very different from your goals at 62.

In this section, we’ll look at how to adjust investments across key milestones, why rebalancing is crucial, and how to build a long-term financial strategy that evolves with you.

10.6.1 Saving and Investing for Major Life Events

Marriage and Partnership

When two incomes join together, financial planning becomes a team sport. Couples should:

-

- Set shared goals (home purchase, travel, kids).

- Decide how to combine or separate accounts.

- Create an investment plan that balances both partners’ risk tolerances.

Buying a Home

Buying property is often the biggest purchase of a lifetime. Key strategies include:

-

- Keep down payment funds in safe, liquid investments (like high-yield savings or short-term bond funds).

- Don’t gamble house money on risky stocks—you need that cash soon.

Kids and Education

Children change everything—including your finances. Parents can:

-

- Use 529 college savings plans (in the U.S.) to invest for education with tax advantages.

- Balance long-term retirement investing with shorter-term goals like tuition.

Inheritance and Legacy

Receiving an inheritance? Consider paying off high-interest debt first, then investing. Leaving an inheritance? Create a will or trust to direct your assets smoothly and reduce taxes for heirs.

10.6.2 Why Rebalancing Matters

Imagine you start with a portfolio of 70% stocks and 30% bonds. After a few years of strong stock performance, your portfolio might shift to 85% stocks and 15% bonds. Suddenly, you’re taking on more risk than you originally intended.

Rebalancing means periodically adjusting your portfolio back to your target mix. You sell a little of what’s grown too much and buy more of what’s lagged. This keeps your risk level consistent.

-

- Young investors: may stick with higher stock allocations.

- Older investors: may rebalance toward more bonds and conservative assets.

It’s like steering a car—you don’t just set the wheel once and hope it drives straight forever. You make small corrections along the way.

10.6.3 Building a Long-Term Financial Strategy

A good strategy is flexible enough to adapt to life’s curveballs, yet disciplined enough to keep you on track. The key elements are:

-

- Set Goals: Retirement, buying a house, college savings, travel, legacy.

- Time Horizons: Match investments to how soon you’ll need the money. (Stocks for long-term, bonds/savings for short-term.)

- Emergency Fund: Always keep 3–6 months of expenses in cash-like assets before focusing heavily on investments.

- Automatic Contributions: Pay yourself first. Set up monthly deposits into retirement or investment accounts.

- Avoid Market Timing: Stay consistent even when markets swing.

10.6.4 Case Studies

Diego and Ana, both 28, want to buy a home in the next three years while also preparing for retirement. To keep things safe, they place their down payment savings in a high-yield savings account—where the money won’t lose value and stays accessible. At the same time, they invest for the long term by putting retirement contributions into stock index funds.

Lesson: Match your investment choices to your timeline. Short-term goals require safety and liquidity, while long-term goals can handle more risk for higher growth.

Sophia, age 40, juggles several financial goals at once—saving for her daughter’s college, paying the mortgage, and investing for retirement. To manage these priorities, she contributes to a 529 plan for education, keeps up with her 401(k), and rebalances her portfolio each year back to 60% stocks and 40% bonds.

Lesson: Life events pile on as you get older. The key is to prioritize, keep balance, and rebalance regularly so no single goal derails the rest.

Mr. Lopez, age 68, has built up $800,000 in retirement accounts. As he enters retirement, he shifts most of his portfolio into bonds and dividend-paying stocks to create steady income he can live on. He also sets up a trust so his grandchildren can inherit smoothly without the delays and costs of probate.

Lesson: Investment strategy changes with life stage. In retirement, the focus shifts from aggressive growth to stability, income, and leaving a legacy.

10.6.7 Tips for Adapting Investment Strategies

-

- Don’t invest short-term money (house down payment, tuition) in risky assets.

- Revisit your portfolio at least once a year—rebalance if needed.

- Use tax-advantaged accounts (401(k), Roth IRA, 529 plans) whenever possible.

- Prioritize retirement savings before kids’ college—there are loans for school, but not for retirement.

- Update your estate documents after major life changes (marriage, divorce, kids).

10.6.8 Final Thought

-

- Life events change your financial priorities—your investments should evolve too.

Whether it’s getting married, having children, or nearing retirement, your financial strategy needs to adapt at each stage. - Rebalancing your portfolio is essential to manage risk over time.

As markets shift, your investment mix can drift—rebalancing keeps your risk level aligned with your goals. - Retirement planning should start early and continue consistently.

Tools like 401(k)s, IRAs, and 457 plans allow for long-term, tax-advantaged growth. Start now, even with small contributions. - Estate planning is not just for the wealthy—it’s for anyone who cares about their family.

A will, trust, and beneficiary designations can prevent stress, confusion, and legal costs for your loved ones. - Automation builds discipline and makes saving easier.

Setting up automatic contributions helps you stick to your long-term plan—even during uncertain times. - Tax-advantaged accounts are one of the smartest tools for wealth building.

Using retirement accounts wisely reduces your tax burden while maximizing future growth.

- Life events change your financial priorities—your investments should evolve too.

- Investing is about putting your money to work in assets like stocks, bonds, mutual funds, and ETFs so it grows over time.

- Risk and return are linked: higher potential returns come with higher risk. Diversification helps reduce risk by spreading investments across different assets.

- Stocks represent ownership in companies and can provide growth through price appreciation and dividends, but they are volatile.

- Bonds are loans to governments or companies, offering steady income with generally lower risk than stocks, though they are sensitive to interest rates and inflation.

- Mutual funds and ETFs make it easy to diversify by pooling money across many securities. Index funds and ETFs are usually low-cost, while actively managed funds charge more.

- Retirement accounts (401(k), IRA, Roth IRA) provide tax advantages that boost long-term savings. Starting early makes a huge difference thanks to compound growth.

- Estate planning (wills, trusts, and beneficiaries) ensures your assets are passed on smoothly and protects loved ones.

Conceptual Questions

- What is the difference between stocks and bonds?

- Give an example of how each one generates returns for investors.

- Explain the concept of risk vs. return.

- Why do riskier investments generally offer the potential for higher returns?

- What is diversification and why is it important in investing?

- Provide a simple example of a diversified portfolio.

- Compare mutual funds and ETFs.

- How do they differ in terms of trading and costs?

- What is the main advantage of investing through a Roth IRA compared to a Traditional IRA?

- Explain the concept of liquidity.

- Which is more liquid: a stock, a bond, or a house? Why?

- What is the difference between growth stocks and value stocks?

- Give one example of each type.

- Why is rebalancing a portfolio necessary over time?

- What role do stock indexes (like the S&P 500) play in investing?

- Why is estate planning (wills, trusts, beneficiaries) important even for people who aren’t wealthy?

Problem-Solving Questions

- Stock Growth

You buy 20 shares of a company at $25 each. The stock price rises to $40.

-

- What is your gain?

- Bond Yield

You purchase a $1,000 bond paying a $60 coupon annually. What is the bond’s yield? - Compound Growth

If you invest $2,000 at 8% annually for 15 years, how much will it grow to? - Mutual Fund vs. ETF Cost

A mutual fund charges a 1.5% fee while an ETF charges 0.1%. If you invest $10,000 and both return 8% before fees, which investment leaves you with more after 20 years? - Roth Advantage

Sara invests $3,000 in a Roth IRA at age 25. By age 65, it grows to $45,000. How much of that $45,000 is taxable when she withdraws? - Rebalancing

Your portfolio starts with 70% stocks and 30% bonds. After a year, stocks rise and now make up 80% of your portfolio. What should you do to rebalance? - Index Fund Growth

If you invest $200/month in an S&P 500 index fund averaging 7% annually for 30 years, roughly how much will you have? - Dividend Income

You own 100 shares of a stock paying $2 per share annually in dividends. How much dividend income do you receive each year? - Risk Check

An investor has 90% of their money in one tech stock and 10% in cash. What is the main risk here, and how could diversification help? - Estate Planning

Luis passes away with $500,000 in assets but no will. Probate costs consume 5% of his estate. How much do his heirs actually receive?

Interactive Challenges

- Quick Quiz: Stock or Bond?

- A loan to the government.

- Ownership in a company.

- Pays dividends.

- Pays a fixed coupon.

- Risk Spectrum

Place the following from lowest to highest risk:

Savings account, U.S. Treasury bond, S&P 500 index fund, cryptocurrency. - Diversify or Not?

You put all $10,000 into Tesla stock. Your friend spreads $10,000 equally across 10 different companies. Who is more diversified? Why? - Growth vs. Value

You buy stock in a trendy tech startup. Is this more likely a growth or value stock? Why? - Liquidity Check

Rank the following by liquidity: checking account, house, corporate bond. - Mistake Hunt

“I don’t need to start saving for retirement until I’m in my 40s—I’ll just contribute more later.”

-

- What’s wrong with this assumption?

- Case Study Snapshot

Emily invests $100/month in an index fund at 22 years old. Mark invests $300/month but waits until 40 to start. Who is likely to have more at retirement? Why? - Estate Plan or Not?

Why is it risky for families if someone dies without a will?