7

By the end of this chapter, students will be able to:

- Differentiate between good debt and bad debt, and evaluate when borrowing makes strategic financial sense.

- Explain the main types of student loans, including their repayment options, forgiveness programs, and long-term consequences.

- Identify and compare types of consumer loans, such as auto loans, personal loans, and buy-now-pay-later plans, including how to calculate total cost.

- Apply debt repayment strategies like the snowball and avalanche methods, and evaluate which approach is most effective based on personal psychology and financial priorities.

- Analyze real-life case studies to understand common borrowing mistakes and how to avoid them through thoughtful planning and financial self-awareness.

7.1 Good Debt vs. Bad Debt

When borrowing helps—and when it quietly destroys your future

Imagine sitting at a café with two friends. One just financed a brand-new car with a 72-month loan. The other is thinking about taking out student loans to go to grad school. Are both making terrible decisions? Not necessarily.

The truth is: not all debt is bad—but not all “necessary” debt is good either. Like many things in personal finance, it all depends on the context, the purpose, and your plan for paying it back.

Let’s break it down.

7.1.1 What Makes Debt “Good”?

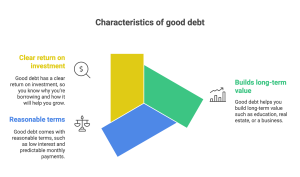

Good debt is money you borrow for a purpose that’s likely to improve your financial future. It may increase your income, expand your opportunities, or build your assets over time.

Good debt typically:

-

- Helps you build long-term value (education, real estate, business).

- Comes with reasonable terms—such as low interest and predictable monthly payments.

- Has a clear return on investment—you know why you’re borrowing and how it will help you grow.

Common examples of good debt:

-

- Student loans for an in-demand career with strong job prospects.

- A reasonable mortgage on your first home (especially if you plan to live there).

- A small business loan—if you’ve got a clear business plan and some experience.

Still, good debt is not magical. It’s still debt. If it’s poorly managed or based on unrealistic expectations, it can quickly become a financial trap.

7.1.2 What Makes Debt “Bad”?

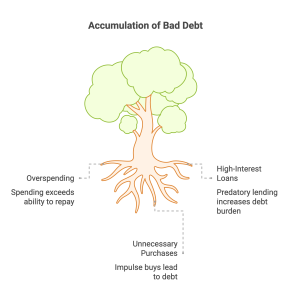

Bad debt is money you borrow for things that don’t grow in value and that drain your resources over time. It often comes with high interest rates, hidden fees, and emotional consequences like stress, guilt, or denial.

Bad debt is typically used for impulse purchases or short-term pleasures that don’t justify long-term payments.

Common examples of bad debt:

-

- Maxing out your credit card for a vacation, new phone, or designer clothes.

- Payday loans, pawn loans, or any loan with interest rates above 20%.

- “Buy now, pay later” deals for things you don’t actually need.

In short: bad debt feels good at the start, but it haunts you later.

7.1.3 How to Know the Difference (In Real Life)

Before you sign any loan, ask yourself:

-

- Will this help me earn more or build wealth?

- Do I have a clear plan to pay it back—without stress?

- Are the terms fair and transparent (low interest, no hidden fees)?

- Will I still feel good about this debt one year from now?

If you answer “no” to two or more of these questions, think twice. You might be walking into a financial trap.

At 25, Sam took out a personal loan to renovate his kitchen. “It’s an investment in my home,” he told himself. But he didn’t make enough income to cover the payments comfortably. Soon, he was putting monthly loan payments on his credit card. Within six months, he was juggling three debts at once—with no breathing room.

Lesson: Just because something sounds like an investment doesn’t mean it’s financially smart. A kitchen upgrade is not worth it if you can’t pay for it without sacrificing your stability.

Nicole took out an $8,000 loan to attend a UX design bootcamp. It lasted six months. She paid $250 per month for three years. After graduating, she landed a remote job making three times her previous salary.

Lesson: The loan wasn’t the solution—it was a tool. Nicole made it work because she had a plan, did the work, and stuck to her payment schedule. The result? A total transformation of her financial life.

7.1.4 If You Already Have “Bad Debt”

You’re not alone. More than half of U.S. adults have carried credit card debt at some point—so if you’re in it, you’re definitely not alone. The first step is not panic—it’s awareness and strategy. Later in this chapter (see Section 7.4), we’ll walk you through realistic ways to get out of debt faster, without shame or gimmicks.

Common Debt Myths—Busted

-

- “All debt is bad.”

False. Smart borrowing can unlock opportunities. - “Only rich people can take out loans safely.”

Wrong. Anyone with a plan and discipline can use credit wisely. - “Paying the minimum is fine.”

Dangerous. Paying only the minimum keeps you in debt for years and makes lenders rich.

- “All debt is bad.”

7.2 Student Loans Demystified

A necessary evil—or a powerful tool? Let’s get real about student loans.

Student loans often get a bad reputation—and in many cases, they deserve it. Stories of people drowning in six-figure debt for degrees they never finished are far too common. But that’s only part of the picture.

Used wisely, student loans can be one of the most strategic forms of debt. The key is understanding how they work, where the traps are hidden, and how to protect yourself from a loan that ends up owning you.

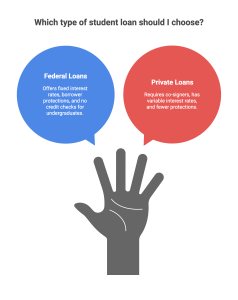

7.2.1 The Two Main Types: Federal vs. Private Loans

Federal student loans

These are loans offered by the U.S. government. They have fixed interest rates and borrower protections. Most undergraduates qualify for them, and they don’t require credit checks.

-

- Direct Subsidized Loans: The government pays the interest while you’re in school. These are for students with financial need.

- Direct Unsubsidized Loans: Interest starts accruing immediately—even while you’re still in school.

- Direct PLUS Loans: Available to graduate students or parents. Higher interest rates. Credit check required.

Private student loans

These come from banks, credit unions, or online lenders. They often require a co-signer and have variable interest rates, fewer protections, and less flexibility.

Use private loans only as a last resort—after maxing out safer federal options.

7.2.2 Understanding Interest: The Hidden Cost of Waiting

Here’s what that means in real dollars.

If you borrow $20,000 in unsubsidized federal loans at 5% interest and make no payments for four years, the interest adds up.

-

- After 4 years, you’ll owe:

$20,000 + $4,400 in interest = $24,400

- After 4 years, you’ll owe:

And that interest gets “capitalized” (added to your loan), so you start paying interest on the interest once you graduate. That’s how student loans grow quietly and dangerously.

7.2.3 What About Loan Forgiveness?

Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF)

This program cancels your remaining federal loan balance after 120 on-time monthly payments (10 years) while working full-time for a qualifying nonprofit or government employer.

-

- Only federal Direct Loans qualify.

- You must be on an income-driven repayment (IDR) plan.

- You have to apply annually and keep detailed records.

Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) Forgiveness

-

- If you don’t qualify for PSLF, federal loans may still be forgiven after 20–25 years of consistent payments under certain plans.

Important: Private loans do not qualify for any federal forgiveness programs.

7.2.4 Should You Consolidate or Refinance?

-

- Consolidation (for federal loans):

Combines multiple loans into one, with a weighted average interest rate. You can also switch to income-driven plans or become eligible for forgiveness. - Refinancing (mostly private):

You take out a new private loan to pay off your old ones—usually to get a lower interest rate. This works only if you have good credit and stable income. But beware: you lose federal protections like deferment, forbearance, and forgiveness.

- Consolidation (for federal loans):

Jonathan borrowed $35,000 in student loans for his business degree. He never realized his unsubsidized loans were accumulating interest from day one. By the time he graduated, the total balance was closer to $42,000. He also didn’t explore forgiveness options until year five—by then, he’d missed critical paperwork.

Lesson: Don’t wait until you’re overwhelmed—be proactive early. Learn how your loans work before you take them, and don’t wait to build a repayment strategy.

Ashley graduated with $28,000 in federal student loans. Her first job paid modestly, so she enrolled in an income-driven repayment plan. After two years working at a public school, she discovered she was eligible for PSLF. She filed the proper forms, recertified her income annually, and tracked every payment. After ten years, her remaining balance was forgiven.

Lesson: Strategy, paperwork, and patience can turn a mountain of debt into a manageable path.

7.2.7 Final Tips for Student Loan Survival

-

- Don’t borrow more than you need. Just because it’s offered doesn’t mean you should take it.

- Start making small payments in school if you can. Even $25/month reduces interest.

- Keep track of your servicer. Your loan might get sold, so always know who to contact.

- Explore scholarships, work-study, and employer assistance first.

- Avoid private loans unless absolutely necessary.

7.3 Consumer Loans: Car Loans, Personal Loans & More

Borrowing for life’s big (and small) moments

Not all debt comes in the form of student loans. Millions of people every year borrow money to buy a car, renovate a home, take a vacation, pay for medical expenses, or consolidate credit card debt. These types of loans fall under the umbrella of consumer loans—and while they’re often marketed as helpful tools, they can quickly become dangerous traps.

Understanding the mechanics behind these loans—and the psychological tricks lenders use to sell them—is essential to protecting your financial health.

7.3.1 Types of Consumer Loans

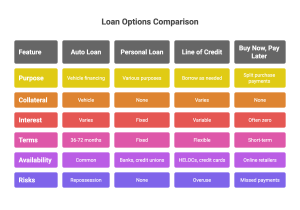

Auto Loans

One of the most common consumer loans. Typically used to finance a new or used car.

-

- Loan terms: Usually 36 to 72 months (3 to 6 years)

- Secured by the vehicle itself (if you don’t pay, the lender can repossess it)

- Interest rates vary based on your credit score, down payment, and loan length

Personal Loans

Unsecured loans (no collateral) that can be used for almost any purpose—debt consolidation, weddings, home repairs, etc.

-

- Fixed interest rates and fixed terms

- Available from banks, credit unions, and online lenders

- Often advertised as “fast cash” with same-day approval

Lines of Credit

Unlike traditional loans, lines of credit let you borrow as needed, up to a set limit.

-

- Examples: Home equity lines of credit (HELOCs), credit cards

- You only pay interest on what you actually use

- Variable interest rates and risk of overuse

Buy Now, Pay Later (BNPL)

Offered by many online retailers. You split a purchase into smaller payments, often with zero interest.

-

- Very convenient—but easy to abuse

- Missed payments can trigger fees and damage your credit

- Often not regulated like traditional loans

7.3.2 What Really Determines the Cost of a Loan?

Many people focus only on the monthly payment, but what really matters is:

-

- Interest Rate (APR) – The total cost of borrowing, including fees

- Loan Term – Longer terms = lower payments but more total interest paid

- Credit Score – Affects your eligibility and the rate you’ll get

- Origination Fees – Upfront costs charged by the lender

- Prepayment Penalties – Some lenders charge you for paying early

Example:

Borrowing $15,000 at a 6% APR over 5 years results in approximately $2,400 in interest—if payments are made on time and in full each month.

Borrowing the same amount at 12% over 7 years costs over $7,200 in interest.

Same loan amount, radically different total cost.

Darien needed a car to get to his new job. At the dealership, he was offered two options:

- A $350/month payment for 72 months on a brand-new car

- A $290/month payment for 36 months on a certified used car

He chose the new car to “feel accomplished.” But by the end of the 6 years, he had paid nearly $25,000 for a car worth $7,000—plus higher insurance, taxes, and maintenance.

Lesson: Monthly payments can be deceiving. Always check the total repayment amount and evaluate long-term value.

Crystal used an online lender to get a $10,000 personal loan for credit card consolidation. It was marketed as “quick and painless,” and she got approved in 10 minutes. The catch? A 21% APR.

She started out fine but missed two payments when her hours were cut at work. Late fees stacked up, and her credit score dropped. When she tried to refinance, no one would approve her. Three years later, she was still stuck with a ballooning balance.

Lesson: Don’t let speed and convenience blind you. Always read the fine print and run the math before accepting a loan.

7.3.3 Warning Signs of Predatory Lending

Some lenders design loans to keep you in debt. Watch out for:

-

- Interest rates above 20% on personal loans

- Loans with very long terms (72+ months) for small purchases

- No credit check required

- Pressure tactics: “This offer expires today!”

- Hidden fees buried in the contract

If it sounds too easy to get the loan, it’s probably because they profit more when you struggle to pay it back.

7.3.4 Smart Borrowing Principles

-

- Never borrow more than you can afford to repay—even on your worst month.

- Compare at least three lenders. Even a 1% difference in APR matters.

- Understand the full cost, not just the monthly payment.

- Look for early repayment options without penalties.

- Have a repayment plan before signing.

7.4 How to Get Out of Debt Without Losing Your Mind

7.4.1 Step 1: Face the Numbers

Before anything else, you need a clear picture of what you owe.

Make a debt inventory:

-

- Who do you owe? (Include every loan, credit card, or payment plan)

- What is the balance?

- What’s the interest rate (APR)?

- What’s the minimum monthly payment?

- Are there any late fees or penalties?

Write it down—or use a spreadsheet or app. This isn’t about shame. It’s about clarity.

7.4.2 The Debt Snowball Method (Emotion-First Approach)

This method focuses on building psychological momentum by starting with your smallest debt.

How it works:

-

- List all debts from smallest to largest (ignore interest rates for now).

- Pay the minimum on all debts—except the smallest.

- Throw every extra dollar at the smallest one.

- Once it’s paid off, move to the next smallest.

Why it works:

You feel early wins. Paying off one account completely gives you a surge of confidence that keeps you going.

Best for: People who are overwhelmed or unmotivated and need quick wins.

7.4.3 The Debt Avalanche Method (Math-First Approach)

This strategy saves you the most money over time by targeting high-interest debt first.

How it works:

-

- List debts from highest to lowest APR.

- Pay minimums on all debts—but throw every extra dollar at the one with the highest interest rate.

- Once it’s paid off, attack the next-highest APR, and so on.

Why it works:

You reduce the amount of interest you pay—sometimes saving thousands.

Best for: People who are math-driven or have large balances with high APRs.

Carlos had five debts—three credit cards, a car loan, and a store financing plan. Instead of tackling the smallest, he ranked them by interest rate. His highest APR card was 26%. He focused all his energy on paying that one down first.

In just 14 months, he cleared three debts and saved over $2,000 in interest compared to the snowball method.

Lesson: The avalanche works if you stay disciplined. Carlos made his plan visible—on a whiteboard in his kitchen.

Crystal had six debts, including old medical bills and store cards. She tried the avalanche method but gave up after three months—it felt too slow. Then she switched to the snowball method. Within two months, she’d knocked out her smallest two debts and finally felt like she was making progress.

Lesson: Sometimes it’s better to gain momentum than to “do the math.” Success builds confidence, and confidence creates consistency.

7.4.4 Other Debt-Busting Tools

Balance Transfer Credit Cards

Move high-interest credit card debt to a 0% intro APR card (usually for 12–18 months).

-

- Watch out for transfer fees (often 3%).

- Never miss a payment—one slip can void the promo rate.

- Use it only if you’re confident you’ll pay most of the balance during the promo period.

Debt Consolidation Loans

Combine multiple debts into one loan with a lower rate and a single monthly payment.

-

- Helpful for simplifying and reducing interest.

- Requires decent credit and stable income.

- Avoid if the new loan has fees or a longer term that increases total cost.

Debt Management Plans (DMPs)

Offered by nonprofit credit counseling agencies. They negotiate with creditors for lower interest rates and combine your payments into one plan.

-

- Your credit cards may be frozen during the plan.

- Usually takes 3–5 years.

- Ideal for people with steady income but too many cards to manage.

7.4.5 What to Avoid

-

- Payday loans: Interest rates can exceed 400%. They trap you.

- Debt settlement companies: They often promise more than they deliver—and can ruin your credit.

- Ignoring your debt: It doesn’t disappear. Avoidance makes it worse.

- Paying only the minimum: It keeps you stuck for decades.

7.4.6 Final Reminders: Action Beats Perfection

-

- Pick one method—snowball or avalanche—and commit to it.

- Automate payments if possible to reduce the mental load.

- Celebrate milestones (first debt paid off, halfway point, final payment).

- Don’t wait for your finances to be perfect. Start where you are.

7.5 Borrowing Lessons from a Strategic Borrower

Most financial education stories focus on cautionary tales—people who borrowed too much and paid the price. This isn’t one of them.

Kevin, the author of this textbook, has never carried credit card debt, never taken out a high-interest personal loan, and never borrowed just to satisfy impulse. That’s not because he’s afraid of debt—but because he sees it for what it truly is: a tool. Like any tool, debt can build something valuable—or cause damage—depending on how it’s used.

In this section, we look at four key borrowing lessons Kevin has learned through discipline, observation, and experience.

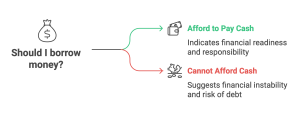

7.5.1 Only Borrow When You Could Pay Cash

Here’s a simple rule that has guided Kevin for over two decades:

If you can’t afford to pay cash, you can’t afford to borrow.

That doesn’t mean you should always pay cash. But it means that if you don’t have the cash, you’re relying on borrowed money to cover a gap in your finances—which is risky. The key is choice. Strategic borrowing is about choosing to use credit, not needing to.

This principle helped Kevin avoid the most common traps: credit card balances, payday loans, and “buy now, pay later” offers that tempt people into spending money they don’t truly have.

7.5.2 Only Borrow When It Makes You More Money

There is one situation where borrowing can be a smart move:

When the money you keep (or invest) earns more than the interest you pay.

Kevin has used this logic in real estate. If a mortgage has a low interest rate—say, 3%—and his available cash can earn 6% through another investment, it makes sense to borrow. That’s a positive spread: his money is working harder elsewhere.

This is not the same as gambling. It only works when:

-

-

You have the cash available to pay off the loan at any time.

-

You’ve done the math on interest rates vs. expected returns.

-

You’ve accounted for risk and liquidity.

-

Strategic borrowers understand this. Emotional borrowers don’t.

7.5.3 Never Borrow Without a Payoff Plan

Borrowing is never a problem—until you don’t know how to pay it back.

Kevin doesn’t avoid debt because he’s scared of it. He avoids it unless there’s a clear, realistic payoff strategy in place. Before taking any loan, he calculates:

-

-

How long it would take to repay

-

What the total cost (including interest) would be

-

Whether he’d still want the item after paying that total cost

-

If the answer to that last question is no, he skips the purchase entirely.

This kind of planning is what separates responsible borrowing from reckless debt. It’s also why Kevin has never paid a cent of credit card interest in his life.

7.5.4 Borrowing Affects More Than Your Wallet

Even when borrowing looks fine on paper, it can still weigh on your mind. Kevin has seen friends and family members fall into “low-level” debt that slowly eroded their confidence. It started with small balances—but it added up. Soon, they were avoiding emails, ignoring statements, or feeling guilt every time they made a purchase.

Kevin has never had that experience—not because of luck, but because of preparation.

Being debt-free isn’t just a financial decision. It’s an emotional one. It means sleeping better. Feeling in control. Saying yes to things you care about without worrying what your lender would think.

7.5.5 What to Teach Yourself Now

Kevin’s approach to debt may sound strict—but it’s actually very freeing. Once you adopt this mindset, you don’t have to wonder whether a loan is “okay” or not. You’ll know.

Here’s a recap of the mindset:

-

-

If you can’t afford to pay cash → Don’t borrow.

-

If you can afford to pay cash, but borrowing allows your money to earn more elsewhere → It might be a smart option.

-

If you don’t have a specific repayment plan → Don’t borrow.

-

If the item will lose value quickly (like a phone, clothes, or vacation) → Don’t borrow.

-

If the loan supports a long-term asset or investment (like education or real estate) → Consider it, but plan carefully.

-

This isn’t about being afraid of debt. It’s about being in charge of your financial future. If you understand your options, stay emotionally detached from the pressure to “buy now,” and only borrow with intention, you’ll stay in control—and that’s the best financial position of all.

7.6 Understanding Interest, Loans, and Debt Strategies

This section provides you with practical tools to evaluate loans, understand how interest works, and make borrowing decisions based on math — not emotion. Use this knowledge to protect your future and make smart financial moves.

7.6.1 Types of Interest

Simple Interest

-

-

Interest is calculated only on the original principal.

-

Formula:

I = P × r × t

where:

I = interest, P = principal, r = annual interest rate (decimal), t = time in years

-

Example:

$1,000 at 5% for 3 years →

I = 1,000 × 0.05 × 3 = $150

-

Compound Interest

-

-

Interest is calculated on principal plus previously earned interest.

-

Formula:

A = P(1 + r/n)^(nt)

where:

A = total amount, P = principal, r = annual rate, n = number of compounding periods per year, t = time in years

-

Example:

$1,000 at 5% compounded annually for 3 years →

A = 1,000(1 + 0.05/1)^(1×3) = $1,157.63

-

Key Insight:

Compound interest grows faster over time. With borrowing, this works against you.

7.6.2 APR vs. Interest Rate

-

-

Interest Rate is the nominal cost of borrowing.

-

APR (Annual Percentage Rate) includes additional fees, origination charges, and reflects the true cost of borrowing.

-

Use APR when comparing different loans.

-

Example Comparison:

Loan A: 6% interest, no fees → APR = 6%

Loan B: 5.5% interest + $500 fee → APR = higher than 5.5% (depends on loan size/duration)

7.6.3 Loan Term and Total Cost

-

-

Longer loan terms = lower monthly payments but higher total cost.

-

Use the amortization formula or loan calculator to compute total repayment.

-

Example:

Borrow $20,000 at 6% interest

-

-

3 years → monthly = $608.44 → total = $21,903.84

-

5 years → monthly = $386.66 → total = $23,199.60

-

Key Insight:

A longer loan seems easier month-to-month but adds thousands in interest.

7.6.4 The 36% Rule (Debt-to-Income Ratio)

-

-

Definition: Lenders use this to decide how much debt you can handle.

-

Rule of thumb: Your total monthly debt payments should not exceed 36% of your gross monthly income.

-

Example:

If you earn $5,000/month:

-

-

Max total debt payments = $1,800/month

(includes mortgage, car, student loans, credit cards)

-

7.6.5 When It’s Mathematically Okay to Borrow

Only consider borrowing if both of these are true:

-

-

You can pay it off comfortably (using 36% rule or less).

-

The expected return on your cash is higher than the interest cost.

-

Example:

-

-

Loan interest: 4%

-

Investment return: 7%

→ You may come out ahead by borrowing and investing the cash.

-

But: This assumes you are disciplined and not just spending the borrowed money.

7.6.6 Bad Borrowing Triggers (to Avoid)

Avoid borrowing in the following situations:

-

-

Just because you’re pre-approved or qualify.

-

You don’t have a payoff plan.

-

It’s a “want,” not a “need.”

-

The interest rate is above 10%.

-

You don’t understand the repayment terms or penalties.

-

You’re using credit to make minimum payments on other debt.

-

7.6.7 Smart Borrowing Checklist

Before borrowing, ask:

-

-

Can I afford to pay cash? (If yes, why borrow?)

-

What’s the total cost of the loan, not just the monthly?

-

Is there an early repayment penalty?

-

Will I make more money by keeping the cash (e.g., investing or running a business)?

-

What’s the worst-case scenario if income drops — can I still repay?

-

7.6.8 How to Pay Off Loans Faster

Debt Avalanche Method:

-

-

Pay minimums on all debts. Use extra money to pay highest interest rate first.

-

Saves more on interest.

-

Debt Snowball Method:

-

-

Pay smallest balance first to gain motivation.

-

Psychological benefit but may cost more in interest.

-

Biweekly Payments:

-

-

Pay half your monthly payment every two weeks.

-

Ends up making 13 full payments per year → faster payoff.

-

Round-Up Method:

-

-

Always round up payments to nearest $10 or $50.

-

Adds up over time with little pain.

-

7.6.9 Default, Delinquency, and Credit Score Impact

-

-

Delinquency: Missing a payment — hurts your credit score immediately.

-

Default: Extended non-payment — may trigger collections or legal action.

-

Impact:

-

Lowers credit score

-

Raises future interest rates

-

May lead to wage garnishment or asset seizure in extreme cases

-

-

7.6.10 Final Takeaway

Use debt like a professional:

-

-

Know your numbers

-

Choose loans strategically

-

Avoid emotional borrowing

-

Always read the fine print

-

Think total cost — not monthly payment

-

If you master this, you’ll stay in control — and ahead.

- Not all debt is bad. Good debt can build your future when tied to income growth or long-term value (e.g., education, housing). Bad debt, like high-interest credit cards or payday loans, drains your finances.

- Student loans are manageable if you plan. Federal loans offer safer options, including fixed interest, flexible repayment, and forgiveness opportunities. Private loans should be your last resort.

- Consumer loans require caution. Whether it’s a car loan or a buy-now-pay-later plan, always calculate total interest and compare lenders before committing. Watch out for predatory tactics.

- Debt freedom starts with a plan. Use the snowball method if you need early motivation, or the avalanche method to save the most money. Automate payments and track progress.

- Mistakes are part of the journey. Real-world debt stories show that emotion and avoidance often create more financial pain than the debt itself. Honesty, discipline, and action build freedom.

Conceptual Questions

- What is a credit card, and how is it different from a debit card?

- Define APR and explain why it is important when evaluating credit cards.

- What does the “minimum payment” represent, and why is it considered a trap?

- Explain the concept of a grace period and how it affects interest charges.

- List and briefly describe three types of credit cards commonly available to consumers.

- What is the difference between a secured credit card and an unsecured one?

- Identify three common fees associated with credit card use and explain how they are triggered.

Scenario-Based Problems

Case Study A: Kevin’s Wake-Up Call

Kevin has a credit card with a balance of $3,200 and an APR of 26%. He’s been paying only the minimum each month, which is around $96.

- What are the financial consequences of only making minimum payments over time?

- What strategies could Kevin adopt to reduce or eliminate this debt faster?

- If Kevin were to stop using the card, how would it affect his credit utilization ratio?

Case Study B: Carla’s Reward Card Decision

Carla is considering applying for a travel rewards credit card that offers 1.5 miles per dollar spent. The card has a $95 annual fee and a 19.99% APR. Carla usually carries a small balance month to month.

- Should Carla apply for this card? Why or why not?

- How do the card’s rewards compare to the potential interest she might pay?

- What other card types might suit her better based on her habits?

Case Study C: Elijah and the Store Card

Elijah was offered a store credit card with 25% off his first purchase. The card has a 28% APR and no grace period.

- What risks should Elijah consider before accepting the offer?

- How could this card impact his credit score over time?

- What questions should he ask before signing up?

Problem-Solving & Financial Calculation Tasks

- Interest Cost Comparison

Jenna has a $1,500 balance on a credit card with a 20% APR. If she only makes minimum payments of 3% each month, calculate approximately how much interest she’ll pay over one year. Compare this to how much she would pay if she made fixed payments of $150 per month. - Grace Period Strategy

Tomas usually pays his full balance every month. In May, he paid only part of his balance and left $400 unpaid.

- If his card has a 22% APR and compounds monthly, how much interest will he be charged in June if he makes no additional purchases?

- How does losing the grace period affect future purchases?

- Payment Planning

Design a payment plan to eliminate a $2,400 balance in 12 months on a card with 18% APR. What is the minimum monthly payment needed? What budgeting adjustments could help free up that amount? - Card Comparison Chart

Research three credit cards (real or hypothetical) and compare them based on: APR, annual fee, grace period, rewards, and additional perks.

- Which card would you choose and why?

- Spending Audit

Track and categorize a hypothetical month of credit card purchases for a student. Then:

- Identify areas of overspending.

- Suggest at least three changes to improve financial health and reduce credit reliance.

- Credit Behavior Self-Check

Write down 5 credit card habits you currently have or think you might develop. Then, for each:

- Label it as healthy or risky.

- Propose an action to reinforce or improve the habit.