10 Cognitive Behavioral Therapy – CBT

Learning Objectives

- Identify and understand the Biopsychosocial influences on behavioral addictions.

- Examine CBT as a therapeutic modality to treat behavioral addictions.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapies- cbt

Behavioral approaches help engage people in drug abuse treatment, provide incentives for them to remain abstinent, modify their attitudes and behaviors related to drug abuse, and increase their life skills to handle stressful circumstances and environmental cues that may trigger intense craving for drugs and prompt another cycle of compulsive abuse. Below are a number of behavioral therapies shown to be effective in addressing substance abuse (effectiveness with particular drugs of abuse is denoted in parentheses).

Behavioral Aspects of CBT

In some cases the primary changes that need to be made are behavioral. Behavioral therapy is psychological treatment that is based on principles of learning. The most direct approach is through operant conditioning using reward or punishment. Reinforcement may be used to teach new skills to people, for instance, those with autism or schizophrenia (Granholm et al., 2008; Herbert et al., 2005; Scattone, 2007). If the patient has trouble dressing or grooming, then reinforcement techniques, such as providing tokens that can be exchanged for snacks, are used to reinforce appropriate behaviors such as putting on one’s clothes in the morning or taking a shower at night. If the patient has trouble interacting with others, reinforcement will be used to teach the client how to more appropriately respond in public, for instance, by maintaining eye contact, smiling when appropriate, and modulating tone of voice.

As the patient practices the different techniques, the appropriate behaviors are shaped through reinforcement to allow the client to manage more complex social situations. In some cases observational learning may also be used; the client may be asked to observe the behavior of others who are more socially skilled to acquire appropriate behaviors. People who learn to improve their interpersonal skills through skills training may be more accepted by others and this social support may have substantial positive effects on their emotions.

When the disorder is anxiety or phobia, then the goal of the CBT is to reduce the negative affective responses to the feared stimulus. Exposure therapy is a behavioral therapy based on the classical conditioning principle of extinction, in which people are confronted with a feared stimulus with the goal of decreasing their negative emotional responses to it (Wolpe, 1973). Exposure treatment can be carried out in real situations or through imagination, and it is used in the treatment of panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, OCD, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

In flooding, a client is exposed to the source of his fear all at once. An agoraphobic might be taken to a crowded shopping mall or someone with an extreme fear of heights to the top of a tall building. The assumption is that the fear will subside as the client habituates to the situation while receiving emotional support from the therapist during the stressful experience. An advantage of the flooding technique is that it is quick and often effective, but a disadvantage is that the patient may relapse after a short period of time.

More frequently, the exposure is done more gradually. Systematic desensitization is a behavioral treatment that combines imagining or experiencing the feared object or situation with relaxation exercises (Wolpe, 1973). The client and the therapist work together to prepare a hierarchy of fears, starting with the least frightening, and moving to the most frightening scenario surrounding the object (Table 13.1 “Hierarchy of Fears Used in Systematic Desensitization”). The patient then confronts her fears in a systematic manner, sometimes using her imagination but usually, when possible, in real life.

Table 13.1 Hierarchy of Fears Used in Systematic Desensitization

| Behavior | Fear rating |

|---|---|

| Think about a spider. | 10 |

| Look at a photo of a spider. | 25 |

| Look at a real spider in a closed box. | 50 |

| Hold the box with the spider. | 60 |

| Let a spider crawl on your desk. | 70 |

| Let a spider crawl on your shoe. | 80 |

| Let a spider crawl on your pants leg. | 90 |

| Let a spider crawl on your sleeve. | 95 |

| Let a spider crawl on your bare arm. | 100 |

Desensitization techniques use the principle of counterconditioning, in which a second incompatible response (relaxation, e.g., through deep breathing) is conditioned to an already conditioned response (the fear response). The continued pairing of the relaxation responses with the feared stimulus as the patient works up the hierarchy gradually leads the fear response to be extinguished and the relaxation response to take its place.

Behavioral therapy works best when people directly experience the feared object. Fears of spiders are more directly habituated when the patient interacts with a real spider, and fears of flying are best extinguished when the patient gets on a real plane. But it is often difficult and expensive to create these experiences for the patient. Recent advances in virtual reality have allowed clinicians to provide CBT in what seem like real situations to the patient. In virtual reality CBT, the therapist uses computer-generated, three-dimensional, lifelike images of the feared stimulus in a systematic desensitization program. Specially designed computer equipment, often with a head-mount display, is used to create a simulated environment. A common use is in helping soldiers who are experiencing PTSD return to the scene of the trauma and learn how to cope with the stress it invokes.

Some of the advantages of the virtual reality treatment approach are that it is economical, the treatment session can be held in the therapist’s office with no loss of time or confidentiality, the session can easily be terminated as soon as a patient feels uncomfortable, and many patients who have resisted live exposure to the object of their fears are willing to try the new virtual reality option first.

Aversion therapy is a type of behavior therapy in which positive punishment is used to reduce the frequency of an undesirable behavior. An unpleasant stimulus is intentionally paired with a harmful or socially unacceptable behavior until the behavior becomes associated with unpleasant sensations and is hopefully reduced. A child who wets his bed may be required to sleep on a pad that sounds an alarm when it senses moisture. Over time, the positive punishment produced by the alarm reduces the bedwetting behavior (Houts, Berman, & Abramson, 1994). Aversion therapy is also used to stop other specific behaviors such as nail biting (Allen, 1996).

Alcoholism has long been treated with aversion therapy (Baker & Cannon, 1988). In a standard approach, patients are treated at a hospital where they are administered a drug, antabuse, that makes them nauseous if they consume any alcohol. The technique works very well if the user keeps taking the drug (Krampe et al., 2006), but unless it is combined with other approaches the patients are likely to relapse after they stop the drug.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) was developed as a method to prevent relapse when treating problem drinking, and later it was adapted for cocaine-addicted individuals. Cognitive-behavioral strategies are based on the theory that in the development of maladaptive behavioral patterns like substance abuse, behavioral addictions, and learning processes play a critical role. Individuals in CBT learn to identify and correct problematic behaviors by applying a range of different skills that can be used to stop drug abuse and to address a range of other problems that often co-occur with it.

A central element of CBT is anticipating likely problems and enhancing patients’ self-control by helping them develop effective coping strategies. Specific techniques include exploring the positive and negative consequences of continued drug use, self-monitoring to recognize cravings early and identify situations that might put one at risk for use, and developing strategies for coping with cravings and avoiding those high-risk situations.

Research indicates that the skills individuals learn through cognitive-behavioral approaches remain after the completion of treatment. Current research focuses on how to produce even more powerful effects by combining CBT with medications for drug abuse and with other types of behavioral therapies. A computer-based CBT system has also been developed and has been shown to be effective in helping reduce drug use following standard drug abuse treatment.

Cognitive Aspects of CBT

While behavioral approaches focus on the actions of the patient, cognitive therapy is a psychological treatment that helps clients identify incorrect or distorted beliefs that are contributing to disorder. In cognitive therapy the therapist helps the patient develop new, healthier ways of thinking about themselves and about the others around them. The idea of cognitive therapy is that changing thoughts will change emotions, and that the new emotions will then influence behavior.

The goal of cognitive therapy is not necessarily to get people to think more positively but rather to think more accurately. For instance, a person who thinks “no one cares about me” is likely to feel rejected, isolated, and lonely. If the therapist can remind the person that she has a mother or daughter who does care about her, more positive feelings will likely follow. Similarly, changing beliefs from “I have to be perfect” to “No one is always perfect—I’m doing pretty good,” from “I am a terrible student” to “I am doing well in some of my courses,” or from “She did that on purpose to hurt me” to “Maybe she didn’t realize how important it was to me” may all be helpful.

The psychiatrist Aaron T. Beck and the psychologist Albert Ellis (1913–2007) together provided the basic principles of cognitive therapy. Ellis (2004) called his approach rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT) or rational emotive therapy (RET), and he focused on pointing out the flaws in the patient’s thinking. Ellis noticed that people experiencing strong negative emotions tend to personalize and overgeneralize their beliefs, leading to an inability to see situations accurately (Leahy, 2003). In REBT, the therapist’s goal is to challenge these irrational thought patterns, helping the patient replace the irrational thoughts with more rational ones, leading to the development of more appropriate emotional reactions and behaviors.

Beck’s (Beck, 1995; Beck, Freeman, & Davis, 2004)) cognitive therapy was based on his observation that people who were depressed generally had a large number of highly accessible negative thoughts that influenced their thinking. His goal was to develop a short-term therapy for depression that would modify these unproductive thoughts. Beck’s approach challenges the client to test his beliefs against concrete evidence. If a client claims that “everybody at work is out to get me,” the therapist might ask him to provide instances to corroborate the claim. At the same time the therapist might point out contrary evidence, such as the fact that a certain coworker is actually a loyal friend or that the patient’s boss had recently praised him.

CBT Worsheets and Treatment Planning Tools

Identifying Issues & Goal Setting

When you start treatment planning with your client, you will need to first establish treatment goals with them. There are many tools that can be used to develop treatment planning, but first you will need to identify the issues and understand the problems that the client is facing.

- Understanding the problem – Goal Setting – CBT Treatment Tools

- Links to an external site.

- Identifying issues CBT worksheet –General+Issues+Worksheet.pdf

- Set SMART goals (Simple, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, Time-bound) –Setting+Goals+Worksheet.pdf

Creating SMART Objectives

Specific

- What will the client specifically do to reach the goal? What specific actions will they take?

Measurable

- Can you count or otherwise quantify the steps the client will take? Could someone observe and determine the skill/action was completed? Can you measure progress through use of a screening tool or questionnaire?

Achievable/attainable

- Is it realistic, given the anticipated length of stay in treatment, that the client will be able to complete the objective?

Relevant

- Is the objective related to the assessment and problem statement?

Time-bound

- What is the timeline the client has for completing the objective? Is the completion date reasonable?

Suggested Tip:If you can see the client doing something, it is an objective (e.g., “make a list of 5 negative consequences related to use”). If you can’t see the client doing something, it is a goal (e.g., “reduce anxiety”).

Applying the CBT Model of Emotions

Emotions are apart of everyday life. Those that come to see you for addiction counseling will have a myriad of many emotions, and some may even have trauma on top of that. For useful and effective counseling to occur, it is helpful to assist your client in identifying, understanding, and accepting the emotions that they may have surrounding seeking help, their addiction, stigmas that may be attached to their addiction, and any emotions they have internally about personal struggles. Every client will be different. Some may have many complex emotions that you will need to sort through, and others may not.

Unlike more complex or traditional forms of talk therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy simplifies the process of understanding and changing emotional processes. According to CBT, there are just a few components of emotion to understand and work with. The benefit of this simpler approach is that it clarifies problems and the solutions needed to solve them such that with a little practice, anyone can understand how to do it.

The Three-Component Model of Emotions

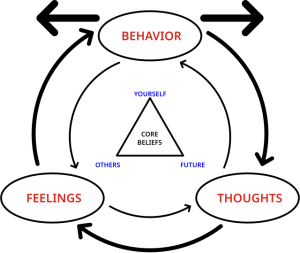

From the CBT perspective, there are three components that make up our emotional experience. They are thoughts, feelings, and behaviors:

Thoughts

Thoughts refer to the ways that we make sense of situations. Thoughts can take a number of forms, including verbal forms such as words, sentences, and explicit ideas, as well as non-verbal forms such as mental images. Thoughts are the running commentary we hear in our minds throughout our lives.

Feelings

The term feelings here doesn’t refer to emotion, but the physiological changes that occur as a result of emotion. For instance, when we feel the emotion of anger, we have the feeling of our face flushing. When we feel the emotion of anxiety, we have the feelings of our heart pounding and muscles tensing. Feelings are the hard-wired physical manifestation of emotion.

Behaviors

Behaviors are simply the things we do. Importantly, behaviors are also the things we don’t do. For instance, we might bow out of a speaking engagement if we feel overwhelming anxiety. On the other hand, if instead we feel confident, we might actually seek out those sorts of engagements.

Thoughts, Feelings, and Behaviors

In a nutshell, a situation unfolds, and our thoughts about it generate feelings, leading to behaviors that influence the situation positively or negatively. This cyclical process repeats, emphasizing the interconnectedness of thoughts, emotions, behaviors, and their impact on ongoing situations.

additional Worksheets & Resources

- Identify the components of emotions worksheet –

Identifying+Components+of+Emotion+Worksheet.pdf

- Example worksheet of components of emotions –

Identifying+Components+of+Emotion+Sample.pdf

References

CBT For Anxiety Disorders: A Practitioner Book. Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, New Jersey. – Simoris, G., Hofmann, S.G. (2013).

Cognitive Behavior Therapy, Second Edition: Basics and Beyond. The Guilford Press: New York. – Beck, J.S. (2011).

Cognitive therapy techniques: A practitioner’s guide (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. Leahy, R. L. (2018).