Learning Objectives

At the end of this section, students should be able to meet the following objectives:

- Explain the preferred use of historical cost as the basis for recording property and equipment and intangible assets.

- Realize that the use of historical cost means that a company’s intangible assets such as patents and trademarks can be worth much more than is shown on the balance sheet.

- Recognize that large reported intangible asset balances can result from their acquisition either individually or through the purchase of an entire company that holds valuable intangible assets.

- Show the method of recording intangible assets when the owner is acquired by a parent company.

Question: Much was made in earlier chapters about the importance of painting a portrait that fairly presents the financial health and future prospects of an organization. Many companies develop copyrights and other intangible assets that have incredible value but little or no actual cost. Trademarks provide an excellent example. The golden arches that represent McDonald’s must be worth billions but the original design cost was probably not significant and has likely been amortized to zero by now. Could the balance sheet of McDonald’s possibly be considered as fairly presented if the value of its primary trademark is omitted?

Many other companies, such as Walt Disney, UPS, Google, Apple, Coca-Cola, and Nike, rely on trademarks to help create awareness and brand loyalty around the world. Are a company’s reported assets not understated if the value of a trademark is ignored despite serving as a recognizable symbol to millions of potential customers? With property and equipment, this concern is not as pronounced because those assets tend to have significant costs whether bought or constructed. Internally developed trademarks and other intangibles often have little actual cost despite eventually gaining immense value.

Answer: Reported figures for intangible assets such as trademarks may indeed be vastly understated on a company’s balance sheet when compared to their fair values. Decision makers who rely on financial statements need to understand what they are seeing. U.S. GAAP requires that companies follow the historical cost principle in reporting many assets. A few exceptions do exist and several are examined at various points in this textbook. For example, historical cost may have to be abandoned when applying the lower-of-cost-or-market rule to inventory and also when testing for possible impairment losses of property and equipment. Those particular departures from historical cost were justified because the asset had lost value. Financial accounting tends to follow the principle of conservatism. Reporting an asset at a balance in excess of its historical cost basis is much less common.

In financial accounting, what is the rationale for the prevalence of historical cost, which some might say was an obsession? As discussed in earlier chapters, cost can be reliably and objectively determined. It does not fluctuate from day to day throughout the year. It is based on an agreed-upon exchange price and reflects a resource allocation judgment made by management. Cost is not an estimate so it is less open to manipulation. While fair value may appear to be more relevant, different parties might arrive at significantly different figures. What are the golden arches really worth to McDonald’s as a trademark? Is it $100 million or $10 billion? Six appraisals from six experts could suggest six largely different amounts.

Plus, if the asset is not going to be sold, is the fair value of any relevance at the current time?

Cost remains the basis for reporting many assets in financial accounting, though the reporting of fair value has gained considerable momentum. It is not that one way is right and one way is wrong. Instead, decision makers need to understand that historical cost is the generally accepted accounting principle that is currently in use for assets such as intangibles. For reporting purposes, it does have obvious flaws. Unfortunately, any alternative number that can be put forth to replace historical cost also has its own set of problems. At the present time, authoritative accounting literature holds that historical cost is the appropriate basis for reporting intangibles.

Even though fair value accounting seems quite appealing to many decision makers, accountants have proceeded slowly because of potential concerns. For example, the 2001 collapse of Enron Corporation was the most widely discussed accounting scandal to occur in recent decades. Many of Enron’s reporting problems began when the company got special permission (because of the unusual nature of its business) to report a number of assets at fair value (a process referred to as “mark to market”)1. Because fair value was not easy to determine for many of those assets, Enron officials were able to manipulate reported figures to make the company appear especially strong and profitable2. Investors then flocked to the company only to lose billions when Enron eventually filed for bankruptcy. A troubling incident of this magnitude makes accountants less eager to embrace the reporting of fair value except in circumstances where very legitimate amounts can be determined. For property and equipment as well as intangible assets, fair value is rarely so objective that the possibility of manipulation can be eliminated.

Question: Although a historical cost basis is used for intangible assets rather than fair value, Microsoft Corporation still reported $50 billion as “goodwill and intangible assets, net” in 2019. Even the size of these numbers is not particularly unusual for intangible assets in today’s economic environment. As of June 30, 2019, for example, the balance sheet for Procter & Gamble listed goodwill of $40 billion and trademarks and other intangible assets, net of $24.2 billion. If historical cost is often insignificant, how do companies manage to report such immense amounts of intangible assets?

Answer: Two possible reasons exist for intangible asset figures to grow to an incredible size on a company’s balance sheet. First, instead of being internally developed, assets such as copyrights and patents are often acquired from outside owners. Reported balances then represent the historical costs of these purchases which were likely based on fair value. Large payments may be necessary to acquire such rights if their value has been firmly established.

Second, Microsoft, and Procter & Gamble could have bought one or more entire companies so that all the assets (including a possible plethora of intangibles) were obtained. In fact, such acquisitions often occur specifically because one company wants to gain valuable intangibles owned by another. In February 2008, Microsoft offered over $44 billion in hopes of purchasing Yahoo! for exactly that reason. Yahoo! certainly did not hold property and equipment worth $44 billion. Microsoft was primarily interested in acquiring a wide variety of intangibles owned by Yahoo! Although this proposed takeover was never completed, the sheer size of the bid demonstrates the staggering value of the intangible assets that today’s companies often possess.

If a company buys a single intangible asset directly from its owner, the financial reporting follows the pattern previously described. Whether the asset is a trademark, franchise, copyright, patent, or the like, it is reported at the amount paid with that cost then amortized over the shorter of its useful life or legal life. Intangible assets that do not have finite lives are not amortized and will be discussed later in this chapter.

Reporting the assigned cost of intangible assets acquired when one company (often referred to as “the parent”) buys another company (“the subsidiary”) is a complex issue discussed in detail in upper-level Advanced Accounting courses. In simple terms, all the subsidiary’s assets (inventory, land, buildings, equipment and the like) are valued and recorded at that amount by the parent as the new owner. This process is referred to as the production of consolidated financial statements. Each intangible asset held by the subsidiary that meets certain rules is identified and also consolidated by the parent at its fair value. The assumption is that a portion of the price conveyed to buy the subsidiary is actually being paid to obtain these identified intangible assets. Thus, to the parent company, fair value reflects the cost that was conveyed to gain the intangible asset.

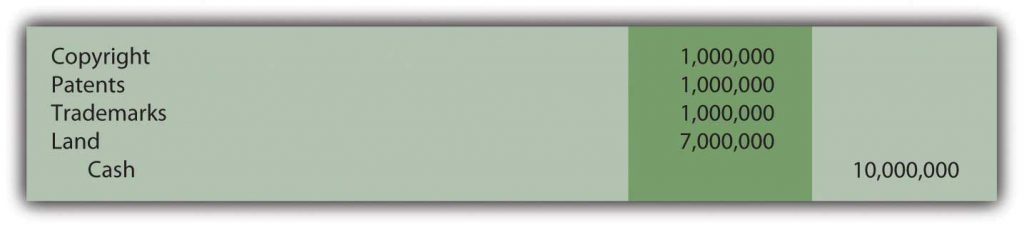

For example, assume Big Company pays $10 million in cash to buy all the stock of Little Company. Among the assets owned by Little are three intangibles (perhaps a copyright, patent, and trademark) that are each worth $1 million. Little also owns land worth $7 million. The previous book value of these assets is not relevant to Big. Following the takeover, Big reports each of the intangibles on its own balance sheet at $1 million. This portion of the acquisition value is assumed to be the historical cost paid by Big to obtain these assets. A company that buys a lot of subsidiaries will often report large intangible asset balances. When Big buys Little Company, it is really gaining control of all of these assets and records the transaction as follows. This entry will lead to the consolidation of the balance sheet figures.

Figure 4.11 Big Company Buys Little Company, Which Holds Assets with These Values

Check Yourself

When acquiring the stock or the entire company in an acquisition, which of the following are true?

A. The acquisition is seldom about gaining control of intangible assets.

B. The acquired intangible assets are recorded on the balance sheet of the buying company at fair value.

C. The cost of the assets to the company being acquired is the most important amount in recording an acquisition.

D. The amounts from the acquired company are kept on separate balance sheets and not consolidated.

The answer is B. The journal entry to record the acquisition of stock debits the newly controlled assets for their fair value with the credit to cash for the amount paid for the stock. Note that in the acquisition of all the stock of a company, stock is not used in the journal entry.

Key Takeaway

Many intangible assets (such as trademarks and copyrights) are reported on the balance sheet of their creator at a value significantly below actual worth. They are shown at cost less any amortization. Development cost is often relatively low in comparison to the worth of the right. However, the reported amount for these assets is not raised to fair value. Such numbers are subjective and open to sudden changes. Furthermore, if the intangible is not held for sale, fair value is of questionable relevance. Companies, though, often pay large amounts to buy intangibles or acquire entire companies that hold numerous intangibles. In accounting for the acquisition of a company, fair value should be assigned to each identifiable subsidiary intangible asset.

1Unique accounting rules have long existed in certain industries to address unusual circumstances. College accounting textbooks such as this one tend to focus on general rules rather than delve into the specifics of accounting as it applies to a particular industry.

2For a complete coverage of the history and ramifications of the Enron scandal, both the movie and the book The Smartest Guys in the Room are quite informative and fascinating.