The Impact of Alzheimer’s Disease on Language

Meghan Bowler

The process of ageing can come with a variety of difficulties, both physically and mentally. Traditionally reflexes get slower, Short-term memory suffers, and the body is impacted with age-related deterioration (Appell et al., 1982). Most can overcome these changes and live very fulfilling years, although some can experience significant impacts from this decline. Several older individuals can experience a breakdown of brain cells, which impacts several areas of cognition, this phenomenon is known as Dementia. Dementia is an umbrella term that can encompass several different types of disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s disease is one of the most common forms of dementia found within elderly patients (Hane et al., 2017). With the significant loss of cognitive functions, it is only natural that several areas of brain functions, including language begin to suffer. While these symptoms are devastating to the effected individual, there are several different therapies that can be considered, but most of the loss of brain cells is permanent.

The underlying cause of deterioration of brain cells that is common in most forms of dementia is largely unknown. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is known as a neurodegenerative disease, which leads to a shrinkage in the brain as the brain cells within deteriorate and die. The underlying reason for the failure in brain cells is not clear, but it has been linked to extending lifespans, which may mean it is a typical factor of the aging process. Due to the devastating failure of the brain, language can be impacted severely as a result. The first sign of this disease is typically a major decline in memory, and a slow signs of speech difficulties begin to surface. Patients suffering from severe Alzheimer’s disease have been seen with difficulties processing language when asked questions, show a significant slowed response, and sometimes do not respond at all (Appell et al., 1982). They can seem almost fluent when they do respond, but the content is usually incoherent or unintelligible. This shows that while they retain basic word pronunciation, they cannot properly produce language in a way that follows proper syntactic form.

Alzheimer’s Disease traditionally begins in middle adulthood, around the age of forty or fifty, with very subtle signs. The more obvious signs tend to come in later when the disease has already impacted the brain, around the mid-sixties. Some of the first signs of Alzheimer’s disease in individuals is noticeable memory issues, which then escalates to other higher cognitive tasks (Hane et al., 2017). Their ability to focus, ability to make decisions, and language can become seriously impacted as the deterioration slowly becomes worse. Patients have been noted to lose the ability to focus in conversations, and will often begin talking about irrelevant issues or stop conversing during mid-sentence. While this is common in most types of dementia, AD is often identified much later within a patient, when severe behavioral and memory issues begin to surface. Patients with AD experience severe language deterioration, behavioral issues, and memory problems that interfere significantly with daily activities. Mild forms of dementia’s do not always impede on everyday life.

Appell (1982) reports that there is a significant lack of ability to find the proper words, and most patients are left with only commonly used words in their vocabulary as a result. Paraphasias, which are known as language errors such as mixing two words together, are extremely common in AD. This could play a significant factor in the incoherent speech reflected in this condition. Their vocabulary is cut down greatly by this disease, and the ability to name objects suffers greatly, with significant difficulties focused on noun retrieval. Appell (1982) noted in a study that while patients with Alzheimer’s could correctly demonstrate how an object was used, they struggled with naming the object, showing that while their understanding of the object was relatively untouched, they lacked the ability to recall proper noun terminology. AD patients were also found to show poor results in word fluency, meaning they could not produce as many words within the context of a timed task as their non-AD counterparts. Although, they showed that in a word-fluency task with no time restrictions, they scored as well as their non-AD counterparts. This shows that their vocabulary seems to be intact after all, but their ability to recall and process the correct responses seems to be impacted.

While memory loss is a large indicator in the presence of Alzheimer’s disease, there is still little known about any other factors that could highlight the disease early on. In a study conducted by Cuetos and colleagues (2006), they looked into possible linguistic indicators that might highlight an early detection in participants. In this study, they took 40 native Spanish speakers, 19 of which had a possible inheritable trait for Alzheimer’s, which was expressed in a mutation of the E280A Presenilin 1 gene. The other participants did not carry this mutation, and each participant was evaluated in grammatical and semantic language tests. While the participants that carried the expressed mutated gene did not seem to differ in linguistic skills overall, it was found that when compared to individuals that did not express this gene, there was a slight variance in how they expressed themselves verbally. It was found that the participants with the mutated gene preformed significantly worse on two tests that explored semantic units, such as meaning behind direct speech and indirect speech, and objective situations that were presented in picture cards. These results could show that there are more early signs of Alzheimer’s disease located in linguistic ability than previously thought, and could help develop ways to find these warning signs much earlier on (Cuetos et al., 2006).

There are several therapies that can help sufferers of Alzheimer’s regain at least some of their linguistic abilities, although in accelerated cases the effects of this disease are traditionally permanent. Noonan and colleagues (2012), looked into object-naming rehabilitation, which is a direct result of memory difficulties that accompany this disease. They used a technique known as Effortless Learning (EL), which has shown success in memory retrieval, but had not been used to elevate word-finding issues. This type of therapy focuses on reinforcing correct responses by eliminating the chance for error. While simplistic in nature, this type of therapy was shown to have a significant effect on AD patient’s memory retrieval for naming objects. EL was shown to help patients with improving their memory, which lead to a better recall of vocabulary. In a study by Arkin (2007), there was a significant slowing of deterioration when patients suffering from AD were regularly exposed to continued socialization and cognitive language focused enrichment tasks. Continuous cognitive stimulation was shown to help patients suffering from AD improve some of their memory loss, and continuous social interaction provided them the necessary language/speech practice to retrieve and focus on present conversations.

In another study, music therapy has shown promising results in helping patients with Alzheimer’s disease regain elements of speech back (Brotons & Koger, 2000). In the study by Broton and Kroger (2000), patients with severe language deterioration due to AD were split into two groups. One group was to attend group conversation therapies at least twice a week, and the other was given music therapy sessions twice a week. This went on for a period of three months. Before they began therapy, they were asked to complete the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) to evaluate their current mental abilities, and they were also given the Western Aphasia Battery (WAB) to evaluate their current linguistic skills. At the end of three months, each group was re-tested in the WAB and their results were compared with the results prior to the therapy. Broton and Kroger (2000) reported that the participants who were in the music therapy group scored significantly better on their second WAB in comparison to their first set of scores.

The effect of Alzheimer’s disease on language can be significant depending on the amount of deterioration of cells in the brain. People suffering from AD have difficulties remembering common nouns, and can find their vocabulary to be significantly down-sized in direct response to retrieval issues (Appell et al., 1982). While there is no reversing the effects of AD when they’ve reached a significant level of decline, patients can slow the overall effects through cognitive enriching stimulation and continuous social interactions. Both noun-association therapy and music therapy have been shown to improve language abilities in AD patients (Arkin, 2007; Brotons & Koger, 2000). Early detection from carriers of the mutated E280A Presenilin 1 gene can help patients counter the effects of AD (Cuetos et al., 2006). While this type of dementia can wreak havoc on language capabilities, early intervention and cognitive enrichment can help stop or slow the progression.

References:

Appell, J., Kertesz, A., & Fisman, M. (1982). A study of language functioning in Alzheimer patients. Brain And Language, 17(1), 73-91. doi:10.1016/0093-934X(82)90006-

Arkin, S. (2007). Language-enriched exercise plus socialization slows cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal Of Alzheimer’s Disease And Other Dementias, 22(1), 62-77. doi:10.1177/1533317506295377

Brotons, M., & Koger, S. M. (2000). The impact of music therapy on language functioning in dementia. Journal Of Music Therapy, 37(3), 183-195. doi:10.1093/jmt/37.3.183

Cuetos, F., Arango-Lasprilla, J. C., Uribe, C., Valencia, C., & Lopera, F. (2007). Linguistic changes in verbal expression: A preclinical marker of Alzheimer’s disease. Journal Of The International Neuropsychological Society, 13(3), 433-439. doi:10.1017/S1355617707070609

Hane, F. T., Robinson, M., Lee, B. Y., Bai, O., Leonenko, Z., & Albert, M. S. (2017). Recent progress in Alzheimer’s disease research, part 3: Diagnosis and treatment. Journal Of Alzheimer’s Disease, 57(3), 645-665. doi:10.3233/JAD-160907

Noonan, K. A., Pryer, L. R., Jones, R. W., Burns, A. S., & Lambon Ralph, M. A. (2012). A direct comparison of errorless and errorful therapy for object name relearning in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 22(2), 215-234. doi:10.1080/09602011.2012.655002

Images:

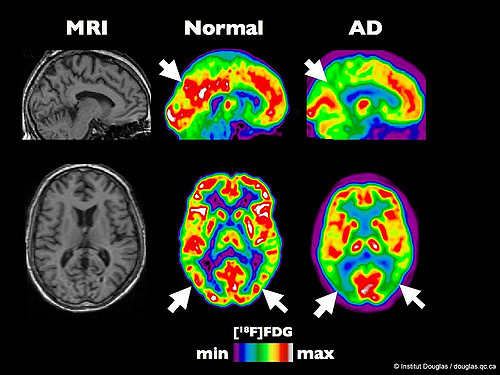

“PET scan of an healthy brain compared to a brain at an early stage of Alzheimer’s disease” by Institut Douglas, Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0). Accessed 12 December 2017. https://www.flickr.com/photos/institut-douglas/2677257668/in/

“Music Therapy Workshop for Alzheimer’s Patients” by Berklee Valencia Campus, Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0). Accessed 12 December 2017. https://www.flickr.com/photos/berkleevalencia/29624046320/in/photolist-MspUYe-M8M6zL-LCqazZ-MzNn3M-LCq5Zg-M