8

What if life left visible marks on you, like a battered wife? On me it does. Like a battered life.

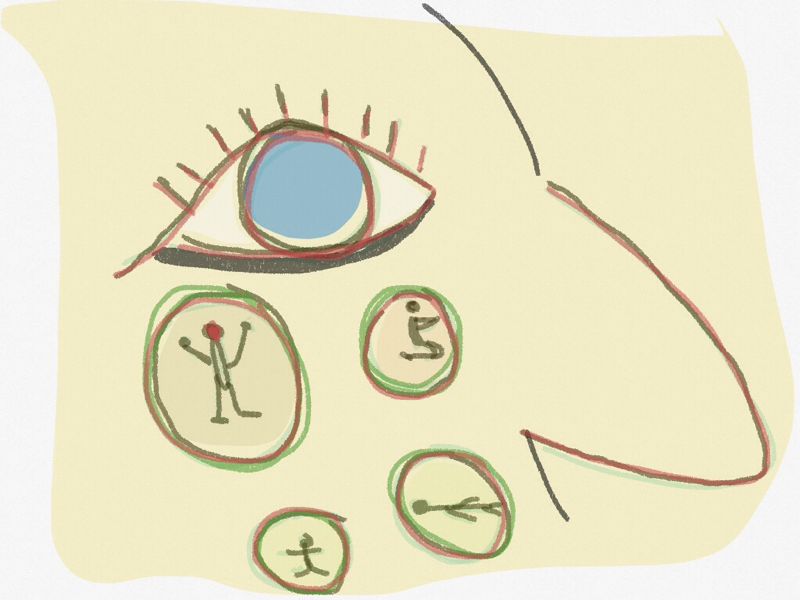

They’re kind of like tattoos with limited color. Blacks, grays, browns of different shades. The images are mostly silhouette-like, except that a few suggestive details are sometimes included. They are a biography of my life in icons.

My birth was premature and I spent several of my first days on a ventilator. Near my belly button is a mark—they call it a birthmark—that is clearly a tiny infant with something over its face. Other people say it’s just a mark, but they’re looking at it wrong.

I was very good in school from the start. A mark on my chest appeared during those years, a small child standing tall and proud. That was surely me.

But I got sick, missed months of school during junior high and fell behind, lost confidence and withdrew. I became introspective, moody and just a little sad. On my temple, about that time, appeared a mark of a child slightly stooped under a tree.

As high school began, I again engaged with the world, but dubiously now. I interacted but did not trust what I heard or what I was being told. Behind an ear I developed a mark of an emerging young man with his back turned towards an adult.

Love seemed unlikely but it came into my life nonetheless at twenty one. She was sweet, shy, an insightful observer and she had a way with words. If she couldn’t explain the world, she at least suggested a sensible way to live in it. Her bemused attitude rubbed off on me, softening my cynicism. She left unexpectedly, but never really left. Her image is still on my right arm.

There was a war, as there always is. I was the proper age to be useful. Though I knew the war was dangerous nonsense, I was drafted and fought. I feared death, but even more feared killing. I did it anyway. I shot several enemy soldiers—who I never saw as enemies. They would have shot me if I hadn’t shot them. We were all forced to follow orders that we resented. That is all wars. Some marks that the war left on me were expected—particularly the shrapnel. Less expected was the picture of me staggered to my knees over the figure of a fallen enemy soldier. That image is on my hip. It often throbs on sleepless nights.

When I came back, I was broke and neither my government nor my “friends” helped me. The politicians who sent me to war and praised my service were happy to ignore me now that I was hungry and homeless. This didn’t surprise me. I had no faith in them ever. My bad knee has the mark of a tough survivor pushing a shopping cart with a posture suggesting a man who was nonetheless prouder than he’d ever been. I felt like a survivor and felt confident that I wasn’t nearly done.

Last week, as I was collecting cans, I walked past a school. There was a commotion so I went inside to investigate. I saw a young man, with a rifle strapped to his shoulder and a pistol in his hand. It was pointed at me.

“What are you doing with that gun?” I asked firmly.

“Don’t get closer!” he screamed. He had the gun but he was the scared one.

“Give me the gun,” I ordered.

Unlike me, he didn’t take the orders.

“I warned you,” he yelled and got off a shot, hitting my shoulder. I had a new mark. It hurt like hell, but I continued to walk toward him.

The young man was crying. He could barely see when I took the gun from him. I told him to go home. A police officer moved in and grabbed him. That’s how I got to be all over the Internet, and television. I was a hero. I refused interviews but all kinds of analysts and commentators “explained” my actions anyway.

No giant “S” appeared on my chest. Instead, there are indelible marks below my eyes. They look just like tears.