Understanding Bloom’s Taxonomy

Educators often use a model of learning called “Bloom’s Taxonomy”. This taxonomy divides learning into categories that instructors can use to specify the learning that they wish to see in their students—and to build assignments and assessments that target those types of learning.

As a student, you can use this model as a way to think more deeply about what you are trying to accomplish when you do an assignment and to understand better the kinds of learning that your professors are asking you to do, even if your professor isn’t using this model intentionally.

A Brief History of Bloom’s Taxonomy

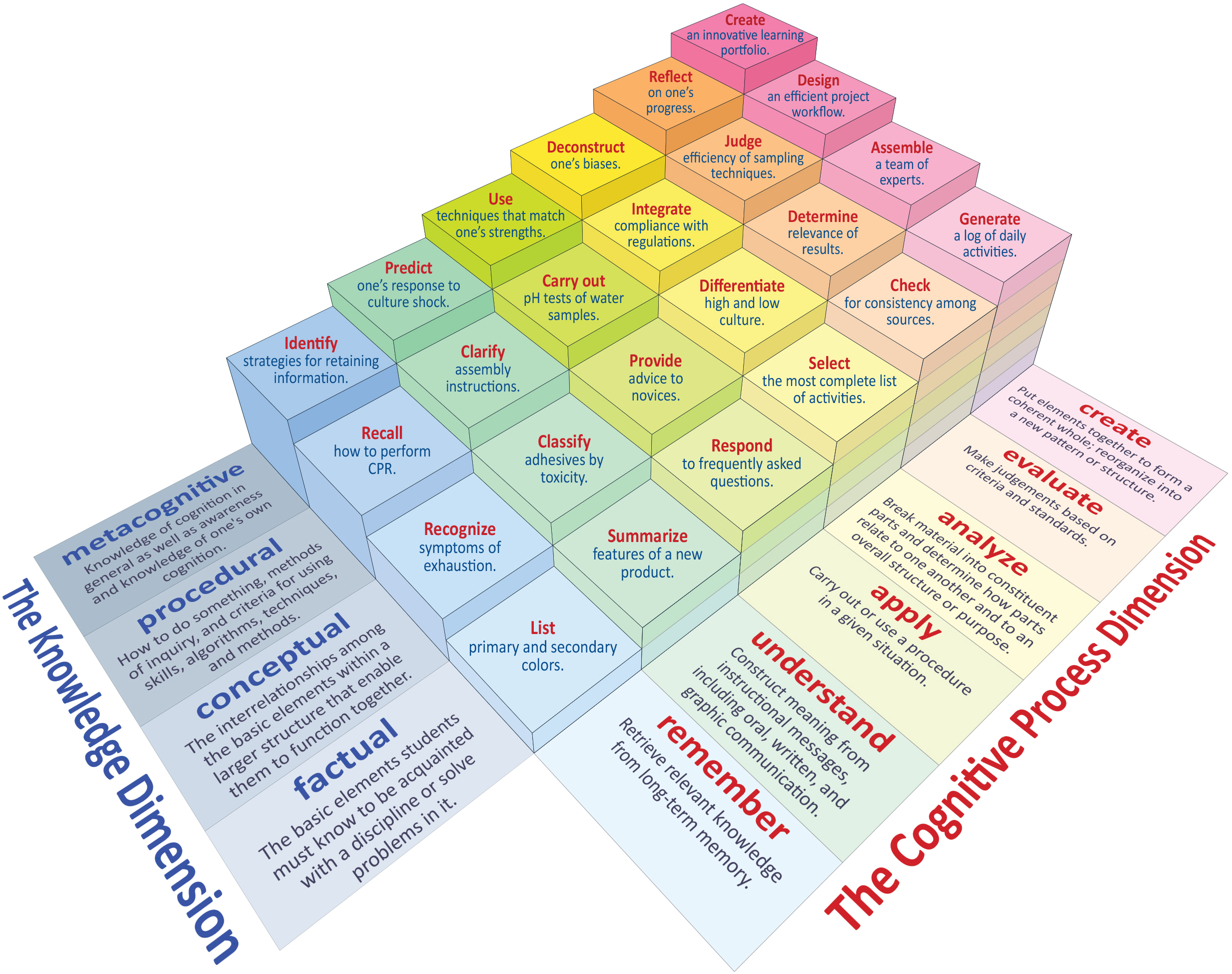

Let’s take a look at one depiction of this model:

I like this model because it incorporates examples of tasks that a professor might ask for, something we will explore in more depth in most of the rest of this section. Before we get into detail, though, take a look at how the model works.

There are four types of knowledge in the revised version, and they move along a continuum from concrete factual knowledge through conceptual and procedural knowledges to metacognition, which is much more abstract than the other types. Then, there are six cognitive processes, listed as verbs: remember, understand, apply, analyze, evaluate, and create.

These are depicted in this figure as a grid, which emphasizes how these dimensions intersect. Notice how the stacks get higher as you move from the factual/remember grid block to the metacognition/create block. This implies that these tasks become more complex as you move “up” the axes. However, as we’ll see, this isn’t always true.

First, let’s look at each of the dimensions.

The Knowledge Dimension

The knowledge dimension lays out the types of knowledge that professors expect students to acquire.

Factual knowledge includes terms, locations, and other listable knowledge. This kind of knowledge often serves as a base for more advanced knowledge.

Conceptual knowledge includes ways of organizing information and ideas, including knowledge of theories and principles. This type of knowledge helps you structure factual knowledge, as well as understand the relationships among information and ideas.

Procedural knowledge includes knowledge of techniques and methods, as well as when to use those techniques. This type of knowledge tends to be subject-specific, so, for example, different majors will use different procedures for identifying and solving problems.

Metacognitive knowledge is sometimes described as “thinking about thinking.” This kind of knowledge involves your ability to take a step back and understand how you think and learn, which is why it’s considered abstract knowledge. You will often be asked to do reflective work in college, and every time you are explaining how you know what you know, you’re practicing metacognition.

You can think about the knowledge dimension as the type of information or ideas that you are supposed to demonstrate and/or work with when you get to the cognitive processes dimension.

The Cognitive Processes Dimension

Notice that the cognitive processes are labeled with verbs (e.g., apply, evaluate). These words indicate action, something you are doing.

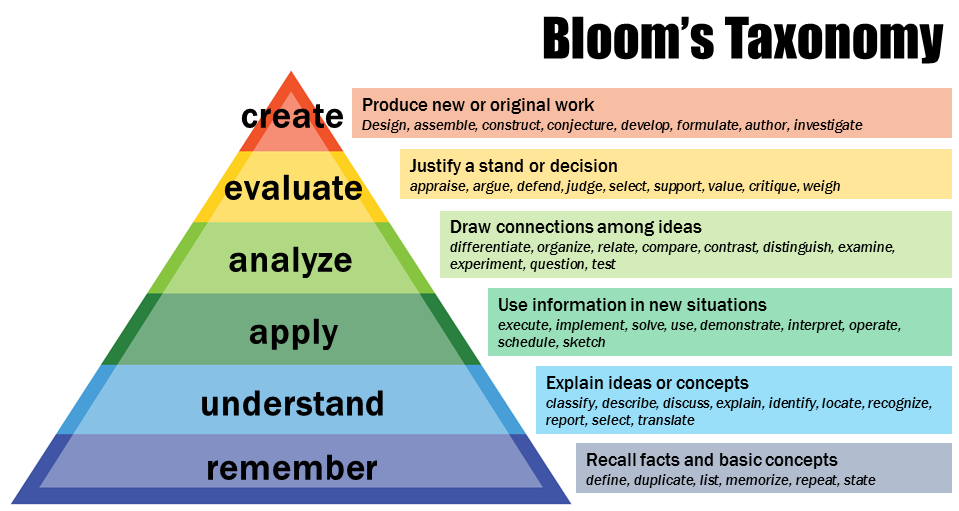

If you search online, you will often see Bloom’s Taxonomy presented as a pyramid like this:

This version of the model focuses on the cognitive processes and ignores the knowledge dimension, but it’s helpful here.

Remembering involves recalling information and ideas. This kind of thinking regularly serves as base for the work you are asked to do in college, but it is rarely an endpoint—and almost never an endpoint in writing assignments.

Understanding asks you to explain information or ideas. Again, this type of thinking often serves as a base for college-level work, but you will see this a bit more often in writing assignments than remembering; frequently, it is the first part of a two-part question (e.g., explain Bloom’s taxonomy and then use it to develop a sample writing assignment).

Applying asks you to take information and ideas from one context and use them in a different context, a somewhat more complex cognitive task than the first two. This kind of cognitive task often takes the form of a writing assignment because instructors are looking for explanations along the way (e.g., describe the learning objectives for this course using Bloom’s taxonomy).

Analyzing asks you to take something apart as a way of understanding it. Analyzing involves showing how your object of study works or how its parts are related or how it is similar to or different from something else. As with applying, analyzing is often done in writing assignments because instructors are looking for explanation (e.g., explain the differences between the original version of Bloom’s taxonomy and the revised version).

Evaluating asks you to make a judgment based on some kind of criteria. Because you have to explain why you believe something is good/bad or better/worse, evaluating is often done in writing (e.g., explain which version of Bloom’s taxonomy is more effective and why).

Creating asks you to make something new. What you make and whether you create it in writing depends heavily on your discipline. Painting a self-portrait, for example, would not be done in writing, though a professor might ask you to write about your experiences. While designing a biology experiment would be done with some writing, you’d focus more on the hypothesis, data gathering methods, and calculations—though, you would almost certainly be expected to write up the results. However, some creating is done entirely in writing (e.g., create a handout explaining Bloom’s taxonomy to other education students).

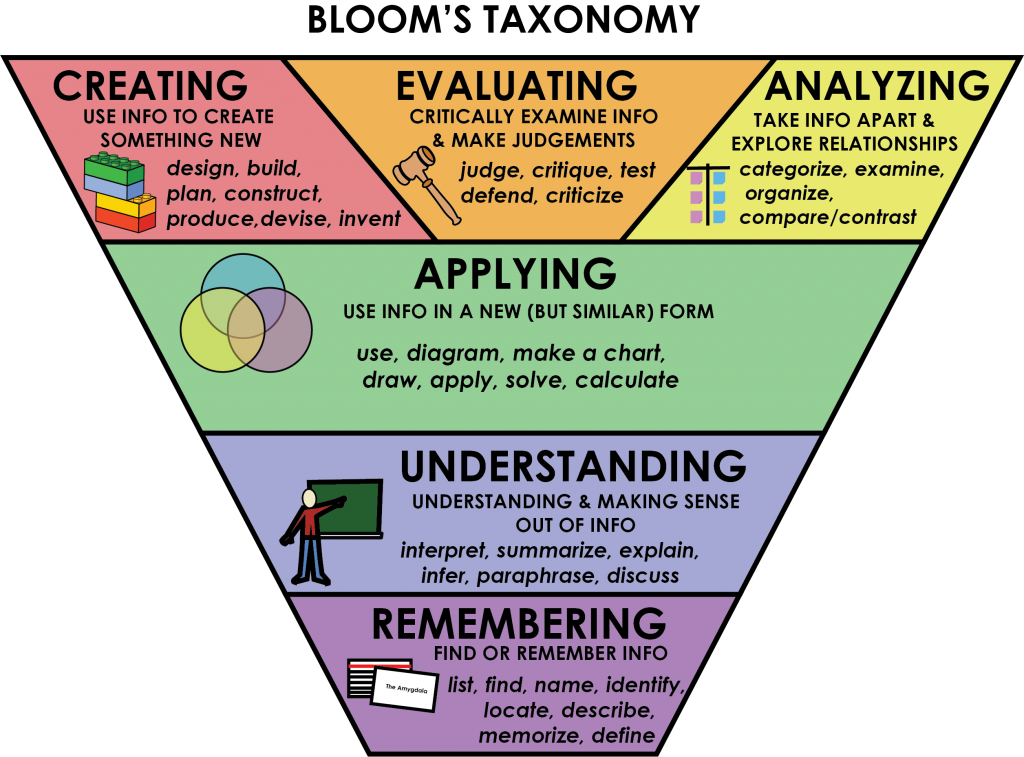

I don’t favor the pyramid because it implies that “remember” is the least important and “create” is the most, but the last three especially are all fairly complex intellectual tasks. To get at this idea, some renditions use an inverted pyramid with analyzing, evaluating, and creating on an equal footing at the top.

LOTS and HOTS

Many educational professionals call remembering, understanding, and applying “lower order thinking skills” (sometimes abbreviated “lots”) and analyzing, evaluating, and creating “higher order thinking skills” (“hots”). The difference is primarily the complexity of the intellectual work required to do one or the other.

In writing assignments and other complex tasks, the “hots” often build on the “lots” so ultimately multiple levels appear in any given work product.

Embrace the Power of “And”

These groupings and categorizations are not hard and fast. When you think about the assignments your professor gives you, don’t worry about trying to force that assignment into one category or another. Embrace the power of “and.” Writing is a complex task, so your professor almost certainly is asking you to do more than one kind of intellectual work.

Taxonomies Break Down

Taxonomies are classification systems, but classifications are rarely as clean as we might like. Think, for example, about the classification of animal species into vertebrates and invertebrates depending on whether an animal has a backbone or not. There are multiple levels of classification that become more and more specific, such as whether a vertebrate is a mammal or a reptile. Each animal can then be sorted.

But then we have the platypus (part mammal, part reptile). Or the bat (part mammal, part bird).

Most taxonomies—and maybe all—eventually breakdown. We run into an edge case that should fit into the categories but doesn’t, not really. How much of a problem that is depends on what you are doing. In our case, it’s not a problem, as long as writers remember that they are being asked to do complex tasks.

Key Points: Understanding Bloom’s Taxonomy

- Bloom’s Taxonomy is one way to understand the intellectual work that your professors are asking you to do. This method works whether your professor is using this model intentionally or not.

- Bloom’s consists of two dimensions: The Knowledge Dimension and the Cognitive Process Dimension.

- The Knowledge Dimension identifies the kinds of information and ideas that you should be working with: factual, conceptual, procedural, and metacognitive.

- The Cognitive Process Dimension identifies the kinds of work that assignments call for: remembering, understanding, applying, analyzing, evaluating, and creating.

- The work you produce in response to your assignments are considered “complex performances,” so they will almost certainly be asking you to do multiple kinds of work with multiple kinds information and ideas.

Text Attributions

This chapter contains material taken from “A Model of Learning Objectives” by Iowa State University’s Center for Excellence in Learning and Teaching and is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

Media Attributions

Grid Model: A Model of Learning Objectives–based on A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives by Rex Heer, Center for Excellence in Learning and Teaching, Iowa State University is used under a CC BY-SA (Attribution-ShareAlike) 4.0 International License.

Pyramid Model: “Bloom’s Taxonomy” by Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching is used under a CC BY (Attribution) license.

Inverted Pyramid Model: “Bloom’s Taxonomy” by ©Rawia Inaim is used under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license.