2 Chapter 2: Judaism

Introduction to Judaism

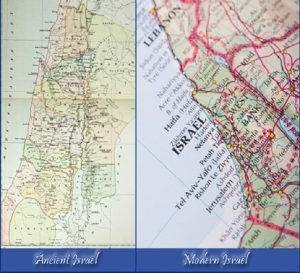

Judaism is a rich and complex tradition that defies easy definition. It’s a religion, a culture, a people, and a nation all at once. These descriptions of Judaism may overlap, but each one has its own unique significance and can stand alone. At its heart, Judaism is an ancient faith with a deep connection to the past. Yet, it’s also a dynamic and living tradition that continues to evolve and adapt to the needs of its followers today. Judaism balances tradition with innovation, making it a vibrant and relevant faith for millions of people around the world. But Judaism is more than just a religion – it’s also a people with a shared history and heritage. Jews can be found in every corner of the globe, from Europe and Africa to the Middle East and beyond. Some Jews practice other religions or none at all, yet they remain part of the Jewish people. Finally, Judaism is closely tied to the modern nation of Israel, established in 1948. This adds another layer of complexity to the term “Jew,” which can refer to a citizen of Israel or a member of the Jewish diaspora.

In this chapter, we will learn about into the religious aspects of Judaism, exploring its beliefs, practices, and traditions. We’ll examine what makes Judaism a unique and enduring faith, and how it continues to inspire and guide its followers today.

- What are the core beliefs and principles of Judaism, and how do they shape Jewish practices and traditions?

- What is the significance of the Torah and other sacred texts in Judaism?

- What is the importance of community and family in Jewish life and practice?

- How has Judaism responded to challenges and conflicts throughout history, such as persecution and assimilation?

- What are the different branches of Judaism (e.g., Orthodox, Conservative, Reform), and how do they differ in their beliefs and practices?

- How does Judaism influence Jewish identity and culture, and how do Jewish values and ethics shape daily life and interactions with others?

The Historical Development of Judaism

Judaism as a religion begins with Abraham. Abraham is presented in the Hebrew Bible as the friend of God. The Hebrew Bible states that Yahweh (the Hebrew name for God) entered into a covenant with Abraham. According to the terms of the covenant, Abraham would worship and obey only Yahweh. In return, Yahweh would bless Abraham with a large family and possession of the promised land—the land of Canaan in the Middle East. According to the Hebrew Bible, Abraham’s wife, Sarah, had a son named Isaac when Sarah was 90 years old, and Abraham was 100 years old.

Isaac became the father of Jacob, and Jacob’s name was later changed to Israel. According to the Pentateuch, which records that God sent Moses to deliver the Hebrew people from Egypt, Jacob had 12 sons, who became the fathers of the 12 tribes of Israel. Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob are known as the patriarchs of Judaism. Although scholars debate the historicity of the Exodus account, according to Jewish tradition, the tribes of Israel migrated from Canaan to Egypt to escape a regional famine.

Eventually, as the story is told, the inhabitants of the nation of Israel became slaves in Egypt, where they lived for hundreds of years after the death of Jacob. Through a series of miraculous events, God persuaded the Egyptian Pharaoh to release the Hebrew people so they could return to Canaan. This event, known as the Exodus, is among the most theologically significant events in the history of Judaism. For Jewish believers, the Exodus symbolizes the intervention of Yahweh (the name used in the Hebrew Bible to refer to God) to save their people.Again, while the historicity of this event is doubted, for modern Jews it is the theological and moral significance of the story that is most important. Certain key elements of the Exodus shaped the nature and development of the Jewish religion.

The first of these elements is the Passover. According to the story, the tenth and final miracle Yahweh performed to secure the deliverance of Israel from Egypt was to send the angel of death throughout the land to kill the firstborn child in each household. Moses commanded the people of Israel to kill a lamb and sprinkle the blood on the doorposts of their houses. They were to gather inside and eat the lamb. When the angel of death came during the night, he would “pass over” any houses with blood on the doorposts and spare the firstborn child. The event is memorialized, even today, in an annual Passover feast.A second theologically significant aspect of the Exodus was giving the Israeli people the Law of Moses. According to the Biblical story, Moses went alone to Mount Sinai, where Yahweh wrote the Ten Commandments on stone tablets. These 10 laws and a host of other ceremonial and civil laws were used to govern the civil and religious life of the nation of Israel and represent God’s relationship with the Jewish people.

The final element to consider is the relationship between Israel and the land of Canaan. For pious Hebrews, Canaan was the land that Yahweh had promised Abraham. For pious Jews, the entry into the “promised land” after the Exodus represents the fulfillment of the covenant between Yahweh and Abraham.

After the tribes of Israel entered the promised land and eradicated most of the indigenous people who lived there, a new phase of Judaism emerged. Judges, and later kings, ruled the nation of Israel. During the time of the judges, worship services were conducted at regional altars with historical significance, such as Shiloh and Shechem, which had connections to the lives of the patriarchs. In the era of the kings, worship services shifted to a central location—the temple in Jerusalem, which Solomon, the son of David, built.

The next significant event in the development of Judaism came in 586 BCE. In this year, the Babylonians invaded Israel and took the people as captives. Many Jews were deported to Babylon or other conquered nations. The temple was destroyed and plundered. Centralized worship ceased to exist.

The Babylonian captivity, as this era has come to be known, changed Jewish theology. Previously, the Jews had primarily practiced a henotheistic religion – a belief that their God (Yahweh) was more powerful than the gods of the peoples who lived around them. They had seen Yahweh as a local deity residing in the temple at Jerusalem. Now they were forced to rethink this position. How could they be the people of God, if God lived somewhere far away? The answer came in the prophetic preaching of Ezekiel and Isaiah, who taught that Yahweh was not a local deity but the God of all the earth. Yahweh was the God of all nations, and even pagan kings were under his authority.

After the Babylonian captivity, the nation of Israel never again had a sovereign king or a land of its own. The Babylonian Empire fell to the Medo-Persian Empire, which Alexander the Great conquered, ushering in the Greek era. Eventually the Greeks fell to the mighty Roman legions. For hundreds of years, the Jews were passed along from one empire to the next, enjoying varying degrees of religious freedom under various rulers, but they always were subject to a stronger nation.

Based on this early history, Judaism did not arise in the context of a stable regional government nor has it remained unchanged throughout its history. Judaism has evolved through cultural and national changes and continues to do so today. Though it is quite ancient, Judaism remains a faith in transition.

The modern history of Judaism begins with the Roman Empire. The Roman Empire was ruled by various emperors throughout its history. Because of the massive size of the empire, regional kings and governors ruled local areas and were accountable to Julius Caesar in Rome. The regional kings in Israel were a family known as the Herods.

Several of the Herods served as kings of Israel under Roman authority. The most well-known is Herod the Great, a character in the New Testament gospels. Herod allowed the Jews to live in relative freedom but held them subject to the laws of the Roman Empire. The Jews were permitted to worship freely and to convene the Sanhedrin, or council of elders, to debate religious issues and enforce religious laws. Herod even funded a major renovation of the temple as a goodwill offering to the Jews.

Faced with political and social pressures, the Roman government began to look with increasing hostility toward Jews and Christians. Under the emperor Nero, a wave of persecutions resulted in the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE and the expulsion of all Jews from the region of Judea. This event is known as the Diaspora. The Jews were scattered across the Middle East, Africa, and Europe, settling in large communities in Alexandria (Egypt), Babylon, and Spain, where a significant Jewish presence already existed. The displaced Jews also established many smaller settlements. Many Jews were assimilated into their new cultures, while others maintained a distinctly Jewish identity.

The Jewish community in Babylon became the intellectual center of Judaism in the Diaspora. Scholars in Babylon continued to research the Law of Moses, seeking interpretations and applications of the law in their new situation. Babylonian Jews produced an expansive commentary on the Torah, called the Babylonian Talmud, around 500 CE.

In the 7th century CE., a new religious force emerged in the Middle East. Islam, which Muhammad founded in Mecca (modern-day Saudi Arabia), spread quickly through Arabia and Africa after Muhammad’s death in 632 CE. In the early days of Islam, Jews lived in relative peace in Muslim-controlled areas and were permitted to study and practice their religion with little interference from Islamic rulers. Muslims appreciated that Judaism, like Islam and unlike many local tribal religions, was a monotheistic religion with a holy book; therefore, Muslims were tolerant of the Jewish faith and its practices.

A good example of the cooperation between Muslims and Jews can be seen in the land of Spain where Jews had lived since the 1st century CE. Jews were permitted almost unlimited freedom of religion and access to various levels of civil service careers. Under Muslim rule, Spain became the worldwide center of Judaism and produced some of the most notable Jewish philosophers and scholars during this era, such as Moses Maimonides.

From Spain, Jews migrated throughout Europe, establishing large communities in Poland, Germany, Portugal, and England. Thriving Jewish communities also existed in India and China. Jews enjoyed more freedom and prosperity under Muslim rule in the Middle East than under Christian rule in Europe in the Dark Ages.

The Middle Ages saw a resurgence of antisemitism in Europe. By 1500, Jews were persecuted in almost every European nation. In 1290, Jews were expelled from England; in 1306, King Philip IV of France (Philip the Fair) expelled all Jews from his country. Throughout the 13thcentury, Jews were systematically chased out of Germany. In 1492 and 1498, Spain and Portugal, respectively, expelled all Jews from their borders. Where did these Jews go? Many found refuge in Muslim countries in the Middle East, while others pushed farther and farther into Eastern Europe, particularly Poland.

Judaism and the Expansion of Zionism

The late 1800s and early 1900s saw yet another increase in antisemitism in Europe, this time culminating in the German Holocaust, during which an estimated 6 million Jews were executed and many more were enslaved. Even before the Holocaust began, many Jews were pressing for change. They longed for a permanent Jewish homeland in the Middle East where Jews could rule Jews, maintain a standing army for their defense, and practice their religion freely. This movement became known as Zionism.

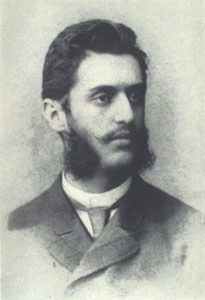

The father of the Zionist movement was Theodor Herzl. Herzl was an assimilated Hungarian Jew; he was a part of the fabric of Hungarian society but did not practice any religion. In his early life, he mocked Judaism and embraced German intellectualism, a philosophy holding that 19th century Germany was the highest civilization in history. Herzl studied law and practiced briefly before pursuing a career in journalism. In 1896, Herzl wrote his most influential book, Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State), in German; it was later translated into English and became the rallying force of Zionism. Herzl and others lobbied the governments of many nations to assist the Jewish people in establishing a Jewish state. Herzl died in 1904 of heart failure, never having seen his dream of a Jewish state come to fruition.

The Zionist movement floundered in the years after Herzl’s death, as new waves of antisemitism swept across Europe. At the end of World War II, thousands of European Jews migrated to present-day Israel, which was a British colony at the time. Many of these Jews were concentration camp survivors. In 1948, Herzl’s dream was realized when the nation of Israel was forced.

What Jews Believe (Solutions to the Problem of Exile)

The Jewish religion is most commonly referred to as a type of ethical monotheism, as it assumes the existence of a Creator God whose benevolence and goodness are reflected in His love for humanity and who has imparted to the Jews ethical principles which they (and the rest of the human race) are expected to follow.

Most important for Judaism is the concept of divine oneness which means that there is only Divine being in the universe; that this one Being is truly incomparable, and no human being (or anything else we can imagine) can be compared to this Being. Judaism’s idea of transcendence presupposes a fundamental difference in reality between God and creation.

Yet, even though God is fundamentally transcendent to creation, He is also immanent (near) to human beings. The very fact that Jews pray to God underscores this belief. Primarily in and through His relationship with His People, God is present in the world and is actively engaged in what happens to human beings. Jews use the word covenant to refer to the bond of love, trust, and forgiveness that exists between God and Israel.

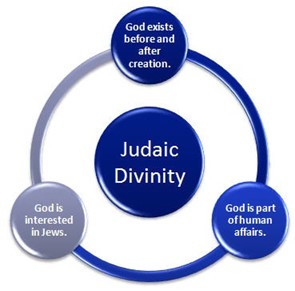

The diagram below illustrates the Judaic concept of God. Within Jewish theology, two central themes emerge. One is that God is transcendent; that is, God’s power, being, and essence are not contingent upon the created order. The transcendence of God is the idea that God exists outside of creation—that God existed before the world was created and will exist after all else has ceased to exist. This transcendent God is in control of all affairs of this world, particularly natural events and the rise and fall of nations.

The other prominent theme of Jewish theology is the idea that this transcendent God will enter human experience, particularly Jewish experience, in the form of the Messiah. Jews historically have held varying views about the Messiah. Some have believed that the Messiah would be a religious leader, like Moses, who would unite Israel under God’s law. Others have believed that the Messiah would be a military leader who conquers Israel’s enemies and establishes peace and prosperity. This latter view of the Messiah was particularly prevalent during Israel’s captivities in Babylon, Persia, Greece, and Rome. Although the Jewish religion historically has waited for the Messiah, not all Jews continue to hold this belief. Reform Judaism, a modern branch of the Jewish faith, teaches that, among other things, a Messiah will not come and should not be sought. The three views of Jewish Messiah are illustrated below:

Many Jews today continue to wait for the Messiah to come, though no consensus exists on the identity or role of the Messiah in relation to the Jewish people.

For pious Jews, however, the focus of faith is not on the future or even the past – but on the present. Unlike most other religious traditions, Judaism does not focus on the “after-life.” In fact, there is no consistent understanding of what happens after death in Judaism. Judaism is a faith that concentrates its attention on living a fulfilled life in the “here and now.”

What Jews Practice (Solutions to the Problem of Exile)

Ethics are central to every religion, and Judaism is no exception. Jewish morality is deontological rather than utilitarian. Deontological ethics are concerned with doing one’s duty, whereas utilitarian ethics are concerned with bringing about the greater good. Of course, neither moral system is strictly interpreted; each has nuances and subtleties that are beyond the scope of this lesson. For the most part, however, Jewish ethics are based on obedience to God’s commands, which is the duty of all people. For example, King Solomon wrote in the Jewish scriptures: “Now all has been heard; here is the conclusion of the matter: Fear God and keep his commandments, for this is the whole duty of man.”

The will of Yahweh is expressed in the Law of Moses as described in the Pentateuch. Jewish ethics essentially are a matter of obedience to that law. At first, simply obeying the law as it was written was sufficient. As time went by, the Mishnah and the Talmud were developed to offer more detailed guidance on how Jews from a different time and place than Moses could obey the law.

Many modern conceptions of obeying the law do not do justice to the Jewish concept of obedience. For example, if you are driving your car, and you do not exceed the speed limit, then you are obeying the law. Traffic officers will allow you to go about your business. If you exceed the speed limit, however, you expose yourself to the possibility of punishment; the traffic officer can issue you a citation, and you will be punished according to the laws of your jurisdiction. In this modern view of law-keeping, a special, positive merit to obeying the law does not exist— only a negative penalty for breaking the law.

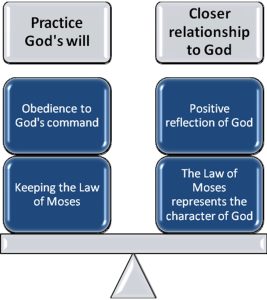

Under the Jewish concept of obedience to the Law of Moses, an exceptionally positive side to keeping the law exists. Jews believe that the Law of Moses is a reflection of the nature of Yahweh himself. That is, the Law of Moses does not simply describe what Yahweh wants the world to be like; rather, it reflects what Yahweh is like. The law reflects Yahweh’s character. When Jews keep the law, they are imitating Yahweh and becoming more and more like God. This divine imitation is the essence of Jewish ethics: if you do what Yahweh says, you will become more like Yahweh and enjoy a closer relationship with him. The graphic below illustrates this concept.

Sacred Texts and Living Law in Judaism (Resources)

Judaism as a religion has revolved around one central text: the Torah. The Torah, or Pentateuch, is composed of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. These books, also known as the books of Moses, contain accounts of the creation of the world, the flood of Noah, the founding of Judaism through Yahweh’s covenant with Abraham, the slavery and liberation of the Jewish people in Egypt, the giving of God’s law through Moses, and the early events in the Jewish conquest of the promised land. The Torah is the primary Jewish religious text, but it often is linked with other books in what is known as the Tanakh. The Tanakh is comprised of the Torah, the Nevi’im (prophetic writings), and the Ketuvim (wisdom literature). The Tanakh is the Hebrew Bible of the Bible.

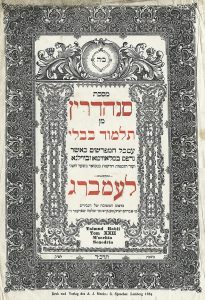

Alongside the Torah, Nevi’im, and Ketuvim, many Jews also recognize another collection of books as sacred. These books are called the Mishnah. The Mishnah is not holy in the sense that the Torah is holy. The Mishnah is not viewed as the divinely inspired words of God; rather, they are the wise insights and commentary on the Torah from prominent rabbis and scholars. The Mishnah contains 63 shorter books that were compiled in 200 CE. These books include summaries and commentaries on the Torah and are designed to make the study of the Torah more profitable.

In addition to the Mishnah, many Jews also recognize the validity of the Talmud. The Talmud is a systematic treatment of the Law of Moses. It is arranged like a legal brief: a law is cited from the Torah, and the opinions of various prominent rabbis are listed. Readers are able to study the various (and sometimes conflicting) interpretations and come to their own conclusions.

The Mishnah and the Talmud are attempts to come to grips with a basic tenet of Judaism: the Law of Moses was given to specific Jews at a specific time and place. While it is the word of Yahweh, it must be interpreted for each generation of Jews in their cultural and historical context. In this sense, the Law of Moses is a living law, flowing and changing in its application for each generation.

Sacred People in Judaism (Resources)

From its earliest days, Judaism has held certain figures as heroes, or holy men and women who were renowned for their wisdom, holiness, strength, cunning, skill in battle, or poetry. The first Jewish sacred people lived in the time before the birth of Abraham. According to the Jewish creation myth, Adam and Eve were the first people Yahweh created and had a special relation to God. Noah was an upright and righteous man; therefore, Yahweh spared him and his family when Yahweh destroyed the earth with a flood in a time of rampant wickedness. Enoch was a holy man who enjoyed such a close relationship with Yahweh that Yahweh took him, alive, into heaven so that he would not have to die.

Abraham introduced the era of the patriarchs. The Torah contains much detail about the adventures of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, including their exploits in battle, their personal struggles, and their worship practices. At the end of Jacob’s life, the Jewish nation was living in Egypt. No new heroes emerged during the Egyptian captivity until the time of Moses. Moses, according to the Torah, was placed in a basket in the Nile River during his infancy to save his life, as the Egyptian king had ordered that all male Hebrew babies were to be killed to reduce their numbers. Yahweh miraculously preserved Moses, after which an Egyptian princess found Moses. She raised Moses as her own son. As a man, Moses came to the aid of a Jewish slave, killing an Egyptian in the process. Banished and hunted, Moses fled from Egypt and wandered in the wilderness of the Sinai Desert. Later, Yahweh appeared to Moses in a burning bush, sending him back to Egypt to deliver the Hebrew people. Moses led the nation of Israel out of Egypt, through the wilderness, and to the border of the promised land. Yahweh did not permit Moses to enter the land.

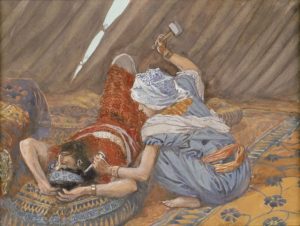

After the tribes of Israel were established in the promised land, a succession of judges ruled the people. These judges were men and women who interpreted the Law of Moses and executed justice among the Jewish people and their enemies. Prominent judges include Samson, a strong man who killed thousands of Philistines, and Gideon, who led 300 men to battle against thousands of Israel’s enemies. Several women are mentioned as well, including the judge Deborah, without whom the generals of Israel would not go to battle, and Jael, a brave woman who snuck into the tent of an enemy warlord and nailed his head to the ground with a tent peg while he slept.

Whereas the judges were primarily military leaders, seen as the human instruments of God in bringing justice to Israel’s enemies, the prophets were religious leaders, speaking the words of God to the Hebrew nation. Some prophets were national leaders, such as Elijah, while others had localized, regional influence. The prophets had two roles. The first was to speak the words of Yahweh to the nation of Israel, often interpreting the role of God in political, economic, or military events. That is, the prophets would explain to Israel what Yahweh was doing in the present. The other prophetic role was to foretell the future. Some prophets, such as Daniel and Isaiah, gave detailed prophecies about what Yahweh would do in the future. Most of these prophecies involved the coming of the Messiah, but others included the rise and fall of nations, the coming of times of famine and war, and events in the lives of kings and leaders.

Israel had many kings during the time of the Hebrew monarchy, but few of these kings are viewed as holy men. Most of the kings were historically inconsequential; some were blatantly wicked. David was the second king of Israel and is viewed as a holy warrior poet. He wrote many of the Psalms, including the often recited 23rd Psalm. David was revered for his holiness, even though he committed the sins of adultery and murder, and for his music and poetry.

Solomon, the third king of Israel, was David’s son. Solomon was viewed as the wisest man who ever lived and, under his rule, Israel’s wealth and stature in the world increased greatly. Solomon is believed to have written three books that became part of the Hebrew Bible: Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and Song of Solomon.

Outside of the biblical record, another political leader stands out. Judas Maccabeus (“Judah the Hammer,” as he was known), was a priest in roughly 167 BCE. During this time, Israel was under the authority of the Seleucid Empire (one of the remnants of Alexander the Great’s conquering army). The ruler of the empire, Antiochus Epiphanes, outlawed Jewish worship. The legend states that Epiphanes sent pagan priests to each synagogue to slaughter a pig on the altar. In Judaism, the pig is an unclean animal; therefore, the act would be seen as a grave insult. When the priest came to the altar of Judas Maccabeus, the legend states, he turned his back on Maccabeus to slaughter the pig. Seizing the opportunity, Maccabeus grabbed a sword and struck down the priest. Then he fled with his sons and many brave young men. They hid in the mountains and waged guerilla warfare against the Seleucid army for approximately 7 years, inflicting great damage on the Seleucid Empire (Holy Bible, New International Version, 1984, 1 Maccabees). This conflict is known as the Maccabean Revolt. The feast of Hanukkah, one of Judaism’s holiest holidays, is held each year in honor of Maccabeus.

Sacred Judaic Spaces and Places (Resources)

Judaism has held certain spaces to be sacred, believing that Yahweh inhabits certain places of religious significance. Five primary sacred places are found in Judaism: altars, the tabernacle, the temple, the synagogue, and the home. In the time of the patriarchs, Judaism was a tribal religion that Abraham and his extended family practiced. This tribal religion had no institutions, traditions, or buildings. Men and women simply worshiped Yahweh. These were nomadic tribes that migrated throughout the area that comprises the nation of Israel today.

During times of particular religious and personal significance, the patriarchs would build an altar of stones in the wilderness and make animal sacrifices on it. Abraham built the two most famous of these altars in Shechem and Shiloh. These became holy sites, and Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob would return to these altars in times of religious significance. Later, the prophets would go to these altars as well to make sacrifices and receive visions from Yahweh. These altars were built before the tribes of Israel went to Egypt.

No holy sites from the time of captivity in Egypt are known to exist. After the Exodus, however, the Jews built a tent called the tabernacle. The tabernacle consisted of a large fabric fence that ringed a courtyard with an altar for animal sacrifice and a tent in which holy items were kept and where it was believed that Yahweh came to dwell with his people.

The next holy place in the Jewish religion was the temple. King David wanted to build a permanent home for Yahweh in Jerusalem. According to the Hebrew Bible,however, Yahweh did not allow him to do this because he had been a violent man, both in his personal life and as a military leader. The task was given to King David’s son, Solomon. Before he died, King David began compiling building material for the temple so that Solomon could begin construction immediately. Solomon built the temple according to his father’s wishes, and it became the central holy site of the Jewish faith. It remained so until 586 BCE, when the Babylonians invaded Israel. The temple was destroyed in the siege of Jerusalem.

Approximately 70 years later, some Jews were permitted to return to Jerusalem, then under the leadership of Ezra and Nehemiah. They rebuilt the temple, although in their poverty and oppression, they were not able to restore it to the splendor of Solomon’s temple. It has been said that when the second temple was dedicated, some of the elders present had seen Solomon’s temple during their childhood. They wept when they saw a building that was small and plain compared to the temple of Solomon.

King Herod funded a major overhaul of the temple, building a larger and more majestic building than even Solomon had done. This temple was built shortly before the birth of Christ; the Romans demolished it 70 CE. No temple exists in Jerusalem today.

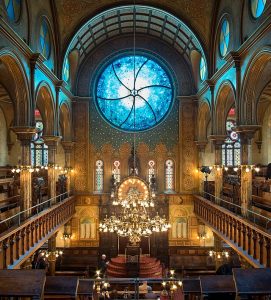

During the Babylonian captivity, a new institution arose among the Jews: the synagogue. Since the Jewish people were geographically isolated from Jerusalem and because the temple had been destroyed, the Jewish people needed a new place for worship. Their solution was to form local synagogues. A synagogue can be anywhere—outdoors, in a home, or in a dedicated building where 10 or more Jewish men and a Torah could be found. At first, these synagogues were public buildings or other convenient meeting places. Later, buildings were constructed in larger cities to serve as synagogues. Some of these synagogues were large and ornate and contained schools and room enough for many worshipers. Other synagogues were quite small and plain. The primary function of the synagogue was the teaching of the Torah, the Mishnah, and the Talmud.

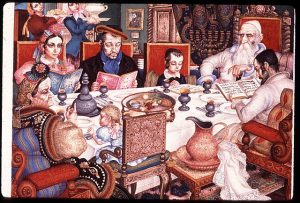

One other holy place in Judaism bears mention: the home. Many Jewish holidays are observed in the family home. Passover, for example, calls for the extended family to gather in one home for a feast, with prominent roles in the ritual for the oldest male and female in the family and for young children. During the festival of Hanukkah, homes are decorated with candles and other ornaments, and meals are celebrated in the home.

Rituals and Celebrations (Resources)

Judaism recognizes several rites of passage during the life cycle of Jews. These rites of passage are birth, coming of age, and marriage.

When a Jewish baby is born, the family and friends observe one of two ancient celebrations. Boys are circumcised on the 8th day after their birth during a ceremony called brit milah (“the covenant of circumcision”). The birth of baby girls is celebrated in a simchat bat (“the rejoicing of the daughter”), or naming ceremony, in which the girl is given her name in the presence of the larger Jewish community. These ceremonies are held to identify the newborn infant with the covenant of Abraham.

The Jewish religion also recognizes two coming-of-age ceremonies: the bar mitzvah for boys and the bat mitzvah for girls. These ceremonies identify the young man or woman as a “son of the commandment” or a “daughter of the commandment,”respectively. Boys traditionally receive their bar mitzvah at 13 years of age, while girls celebrate their bat mitzvah at 12 years of age. After the ceremony, the young person is considered an adult member of the Jewish community.

Marriage is the third phase of the life cycle. Jewish weddings are seen as representative of the covenant between Yahweh and Israel. Traditionally such occasions are taken quite seriously and are celebrated with lengthy and intricate ceremonies. The bride typically is the focus of the wedding ceremony, along with singing, dancing, feasting, reciting of vows, and speeches. Traditionally, the Jewish community pronounces blessings in unison on the newly married couple to invoke the favor of God on their marriage.

These phases of the life cycle are seen as sacred times—a continuation of God’s covenant with the Jewish people.

Death and the Afterlife in Judaism

Judaism teaches that the Jews are God’s chosen people. This idea also extends to their views of death and the afterlife. There is no unified, monolithic Jewish theology of the afterlife, but rather, several views may be held within the Jewish community. One system of thought holds that the messiah will finally usher in the final age and will bring all the Jewish people together in Paradise, or in Israel, depending on one’s theological viewpoint. However, not all Jews are awaiting a messiah. Some Jews believe that each person has an immortal soul which will go to heaven, while others believe that there is no conscious existence beyond this life. Some Jews believe in the resurrection of the dead on judgment day, while others believe that their souls will be in heaven, but will not inhabit bodies. Other Jews regard these beliefs as obsolete and no longer a part of contemporary Jewish faith.

Judaism and Zionism Today

To understand Judaism today, one must understand the concept of Zionism. Zionism is a movement promoting the establishment of a permanent, sovereign Jewish nation. The dream of the Zionists became a reality in 1948 with the establishment of the nation of Israel, but the issue continues to be problematic and plays a major role in the practice of Judaism today.

The ancient nation of Israel ceased to exist as a sovereign state during the Babylonian captivity of 586 BCE., and Jews have been scattered across the world with no central religious or civil structure since the Diaspora of 70 CE. Since then, Jews have assimilated into many cultures throughout the world and have maintained pockets of Jewish existence in several major cities. All this time, many Jews dreamed of returning to the land of their ancestors. The rampant antisemitism of the late 1800s and the Holocaust of the 1930s and 1940s was a catalyst in the formation of the state of Israel in 1948.

The central problem that Zionism proponents faced was location. The land that would become the nation of Israel was populated with various Arab groups and had been that way for generations. A centralized Arab government did not exist, and the population of the area was sparse; therefore, many Jews envisioned living side-by-side with the local Arabs in peace. In some areas, this has happened; in other areas, violence has erupted between Jews and Arabs and continues today. Throughout its brief history, the state of Israel has faced not only violence within its borders but also war with several of its neighboring nations, including Egypt, Lebanon, Iraq, and Syria.

The issue of an Israeli homeland is hotly debated on each side. Should Israel exist as a sovereign nation on lands that other races of people previously occupied? What role should indigenous Arabs, who may be Muslim or Christian, play in a Jewish government? These questions will continue to be debated in the synagogue, the mosque, the church, and the halls of government, and they will continue to shape the religion of Judaism for years to come.

Chapter Review

To learn more and review the key concepts presented in this chapter, watch:

- Crash Course Religions: What does it mean to be Jewish?

Glossary

Altar: A stone table (built in various outdoor locations and in the temple and tabernacle) that Jews used for the burning of animal sacrifices.

Anti-Semitism: Racial or religious hatred toward Jews.

Atheism: The belief that no god exists.

Babylonian Talmud: Text that Jews in Babylon around 500 CE wrote and which interprets and expounds on the Torah.

Bar mitzvah: Ceremony for Jewish boys that signifies initiation into adulthood.

Bat mitzvah: Ceremony for Jewish girls that signifies initiation into adulthood.

Brit milah: Circumcision ceremony for Jewish baby boys.

Deontological ethics: System of ethics based on doing one’s duty, usually based on a divine command or on a sense of universal obligation.

Diaspora: The expulsion of all Jews from the region of Judea between the 4th and 2nd century BCE

Exodus: A book in the Pentateuch or the event (i.e., the departure of the nation of Israel from Egypt, where they had been enslaved) the book describes.

German Holocaust: The systematic killing of Jews in Germany, Poland, and surrounding areas at the hands of the German military under Adolf Hitler in the 1930s and 1940s.

German intellectualism: Philosophy holding that early 19th century Germany was the highest civilization in history.

Hanukkah: Jewish festival commemorating the Maccabean revolt.

Nation of Israel: The Jewish state in the Middle East, founded in 1948.

Maccabean revolt: A series of guerilla warfare skirmishes between Jewish freedom fighters and the ruling empire during the 2nd century BCE

Messiah: Hebrew term meaning “anointed one”; the religious, military, or political savior whom the Jews believe will come to Israel.

Mishnah: Collection of commentaries on the Torah that prominent Jewish scholars have written.

Monotheism: Belief in only one God (e.g., Judaism, Christianity, and Islam), as opposed to the belief that no gods exist or that more than one god exists.

Passover: Jewish festival commemorating the Exodus.

Patriarchs: Literally, “ancient fathers”; in Judaism, the patriarchs are Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

Pentateuch: The first five books of the Hebrew Bible, also known as the Law of Moses, or the Torah.

Polytheism: The belief that more than one god exists.

Simchat bat: Naming ceremony for Jewish baby girls.

Synagogue: Decentralized place of worship and for teaching the Torah.

Tabernacle: Portable tent and courtyard used as a centralized place of worship immediately after the Exodus.

Tanakh: The complete Hebrew Bible.

Talmud: Systematic collection of interpretations of the Law of Moses.

Temple: Centralized place of worship in the Hebrew Bible; believed to be the original temple that Solomon built and later rebuilt or the temple that King Herod constructed, both on the same site in Jerusalem.

Torah: See Pentateuch.

Utilitarian ethics: A system of ethics based on bringing the greatest good to the greatest number of people.

Zionism: A political and religious movement for the creation of a sovereign Jewish nation.