Chapter 10 Setting the Stage for Change

by Sandra Collins, Gina Ko, Yevgen Yasynskyy, Don Zeman, Simon Nuttgens, and Anita Girvin

In the first nine chapters of this ebook we walked you through the following processes as a foundation for building responsive relationships with clients:

- Welcome actively all clients and build care-filled relationships with them.

- Create cultural safety and explore client presenting concerns.

- Apply a trauma-informed practice lens to support power-sharing with clients.

- Engage in a multidimensional exploration of client lived experiences.

- Attend to client perspectives and needs, including what you do together and how you do it.

- Co-construct collaboratively a shared understanding of client challenges and preferred lived experiences.

- Position client challenges and preferences within their cultural identities, worldviews, and the sociocultural contexts of their lives.

Our intention in this ebook is not to explore options for change processes (interventions). However, there are a couple of other important topics that set the stage for change that we do address in this chapter: (a) creating an orientation to change to prepare clients to engage collaboratively in change processes, and (b) setting therapeutic directions to inform the nature and target of those change processes. It is also important to plan in advance for how you will know that change has occurred: for example, through routine outcomes monitoring.

Figure 1

Chapter 10 Overview

Recommended additional reading

Collins, S. (2018). Collaborative case conceptualization: Applying a contextualized, systemic lens. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 556–622). Counselling Concepts.

- Chapter 15 (Core Competency 14: Position client presenting concerns and counselling goals within the context of culture and social location.)

RESPONSIVE RELATIONSHIPS

A. Orientation to Change

When I was a graduate student in a practicum placement, I picked up a number of clients who had been working with one of my supervisors. In the first session with one of these clients, I discovered that they had been coming to the clinic once a week for the past 25 years to see the same therapist. Twenty-five years! I could not wrap my mind around this information, but it seemed like an important starting place for our work together. In the next session I invited them to talk about what had worked well in that previous therapeutic relationship and what they had been working on most recently. The client expressed appreciation for the accepting and caring relationship with her previous counsellor, but she was unable to answer the second question. It did not appear that there was any particular direction or goal for counselling. The client did not seems to understand that their lived experiences might be different as a result of their engagement in counselling. They came once a week for tea with a person who cared about them and listened to their stories.

As I pondered this situation over the first few weeks of building a relationship with this client, I looked for opportunities to invite small shifts in how we approached our time together. The client was grieving the loss of the weekly engagement with my supervisor, so I invested intentionally in building a new relationship with them. I discovered through our conversations that the client was an artist, and they spent most of their time, and their limited financial resources, on their art. They did not sell their art or have any formal training, but making art was the love of their life. It was the thing that sustained them in otherwise quite challenging life circumstances. However, the client had never considered integrating art into their healing journey. As someone who also loved art, I found this revelation difficult to process as well. When I asked them if they would like to bring in some of their art for us to talk about, the client was both excited and hesitant. I encourage them not to pick up any expectations or pressure from me and just to do what felt appropriate for them.

We spent the next six months centring our conversations around the client’s art. Sometimes they had stories to tell about a particular piece. Sometimes the art was a way of expressing an emotion. Other times the art opened up bits of light and hope for the future—a form of identifying exceptions I suppose. I felt a great sense of privilege at being invited into this part of the client’s world, and over time, we both noticed changes in their perspectives and behaviour. They started to share their art with a couple of other significant people in their life. They reclaimed space in their home to give them a more pleasant and light-filled environment for their creative time. And, they started to talk about a dream for their future that they had buried long before under a pile of life struggles and disappointments.

As we neared the end of my practicum placement, the client decided that they wanted to invite their previous therapist (my supervisor) into our therapeutic space and conversations. We spent time making a plan that would best meet the client’s needs. I booked the agency boardroom for a morning, and the client invited their previous therapist to join us for tea. Before our meeting time, the client filled the boardroom walls with their art. They displayed it in a meaningful, but not always chronological, representation of the last six months of their work within, and outside of, therapy. I became the silent guest as the client invited their previous counsellor into their growth experience, walking through some of what they had discovered about themselves, their life, their strengths, their desires, their dreams. Toward the end of the time together, the client shared with both of us that they had applied and been accepted at a prestigious school of art.

I carried forward a number of importance lessons from my experience with this client:

- Although the relationship is essential to creating a therapeutic space, relationship-building alone may not be sufficient to support growth and healing.

- My role, as counsellor, is to look for opportunities to create space for growth and change in a way that is responsive to the specific client I am working with.

- Change is not always linear, predictable, or controllable. Sometime change just happens when you bring together the right set of ingredients in an environment in which change is both welcomed and expected.

Sandra

We begin this chapter by exploring client orientation to change. Norcross and Wampold (2018) argued:

The goal is for an empathic therapist to collaboratively create an optimal relationship with an active client on the basis of the client’s personality, culture, and preferences. When a client resists participating in the therapeutic procedures of a treatment, for example, then the therapist considers whether [they are] using an approach that the client finds incompatible with [their] values, attitudes, culture, or beliefs (preferences), or the client is not ready to make those changes (stage of change) or is uncomfortable with a directive style (reactance). Clinicians strive to offer a therapy that fits or resonates to the [client’s] characteristics, proclivities, and worldviews. (p. 1891)

Much of our focus in this ebook has been on the goodness-of-fit for each client of the relationship-building process and the conceptualization of client lived experience. We posed the following core question in Chapter 1: How can I shift, adapt, or alter my ways of being, relational practices, and approach to counselling in response to the specific cultural identities, contexts, values, worldviews, and needs of the specific client with whom I am working? As we continue to consider this question, we reflect on the process of preparing for change from a critical perspective that attends to cultural worldviews and social locations.

1. Client Readiness for Change

The special edition on evidence-based responsiveness in psychotherapy included an article by Krebs et al. (2018) on the relationship of stages of change to therapeutic outcomes. They concluded that clients at higher stages of changes are more likely to benefit from, and experience, positive outcomes from therapeutic change processes.

Stages of change

The stages of change model was originally developed in the 1980s and is now positioned within a transtheoretical or integrative approach to change (Norcross & DiClemente, 2019). If you are not familiar with the stages of change, you may find the video below informative.

© Practical Psychology (2021, April 18)

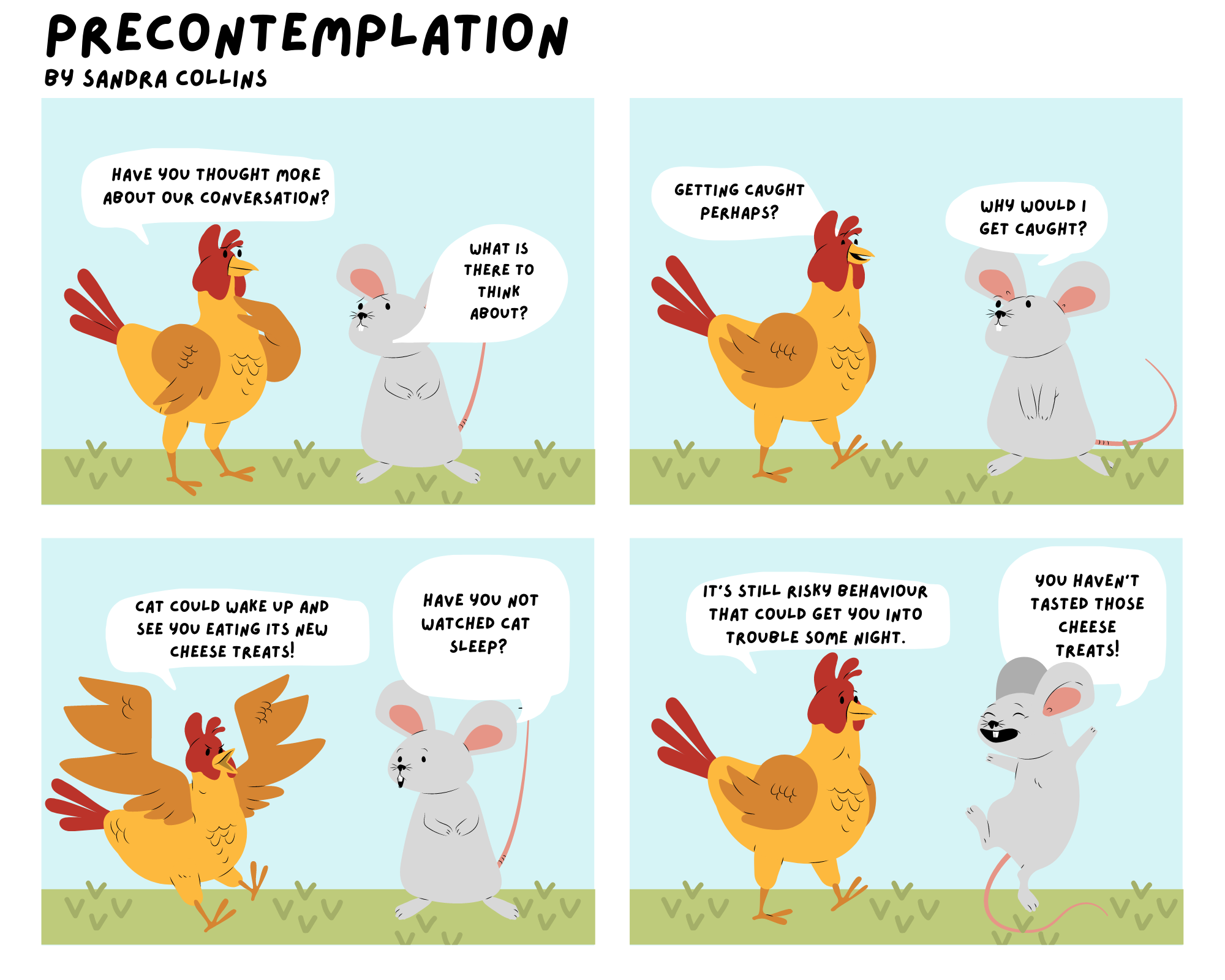

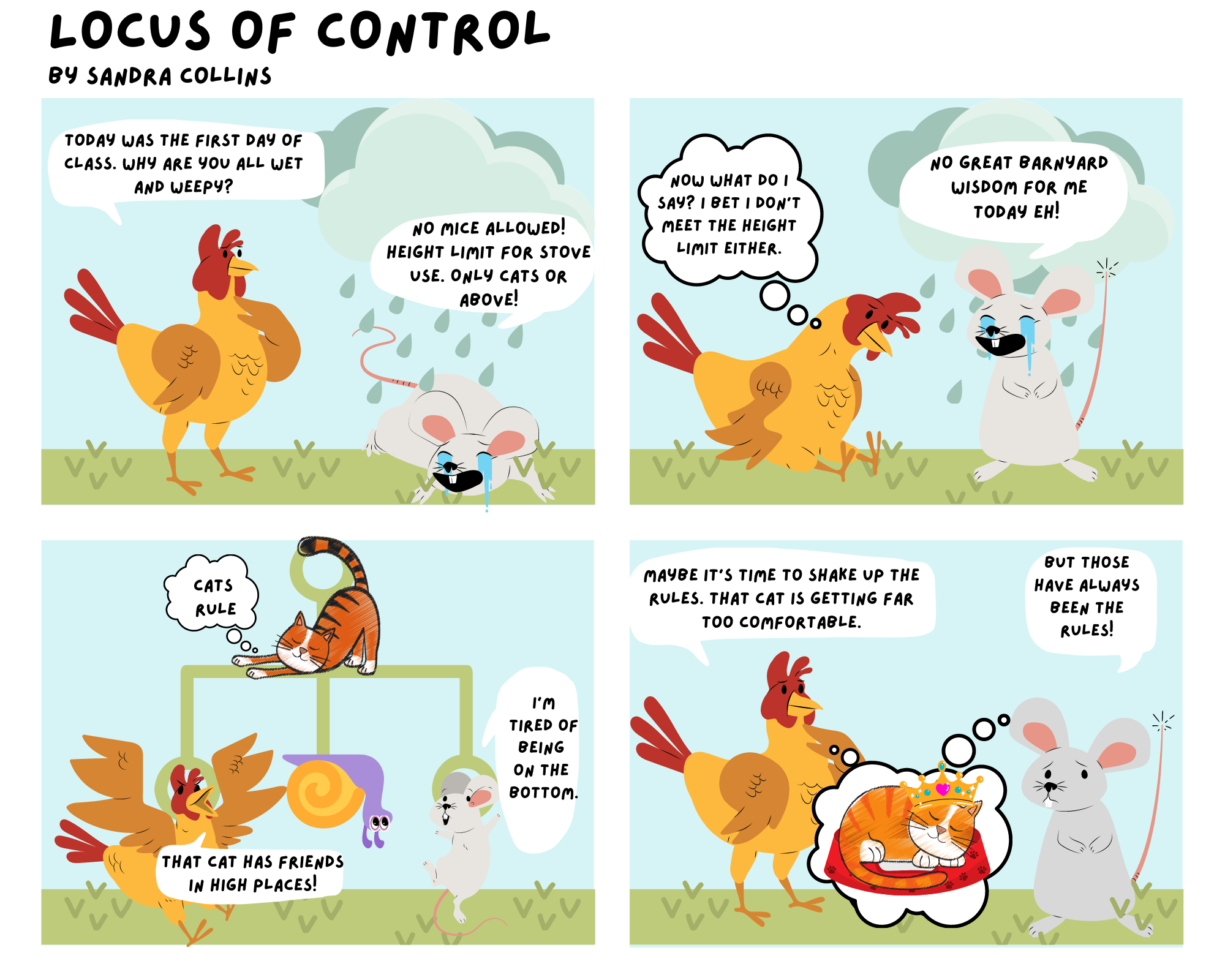

Krebs et al. (2018) positioned these stages of change within the client–counsellor relationship, noting that the relationship must be responsive to, and supportive of, movement of the client from one stage to the next. We focus on the first three stages below that support the client to prepare for change. Consider the following barnyard exchange.

At this point clients may be unaware or unconvinced that there is a challenge that is negatively affecting their health and well-being. Krebs et al. (2018) pointed to the importance of assuming a nurturing stance with clients at this stage.

At this point clients may be unaware or unconvinced that there is a challenge that is negatively affecting their health and well-being. Krebs et al. (2018) pointed to the importance of assuming a nurturing stance with clients at this stage.

- What might this nurturing stance look like for you as a practitioner?

- What relational concepts, principles, and practices might be particularly useful to clients in the precontemplation stages?

- Recall the video by Amy Rubin in Chapter 3 in which she described her experience of developing rapport and trust with clients mandated to engage in counselling. Amy’s relational and respectful approach to her clients supported a movement from precontemplation (i.e., I don’t want to be here) to contemplation (i.e., O.K. Maybe I do need to work on this.).

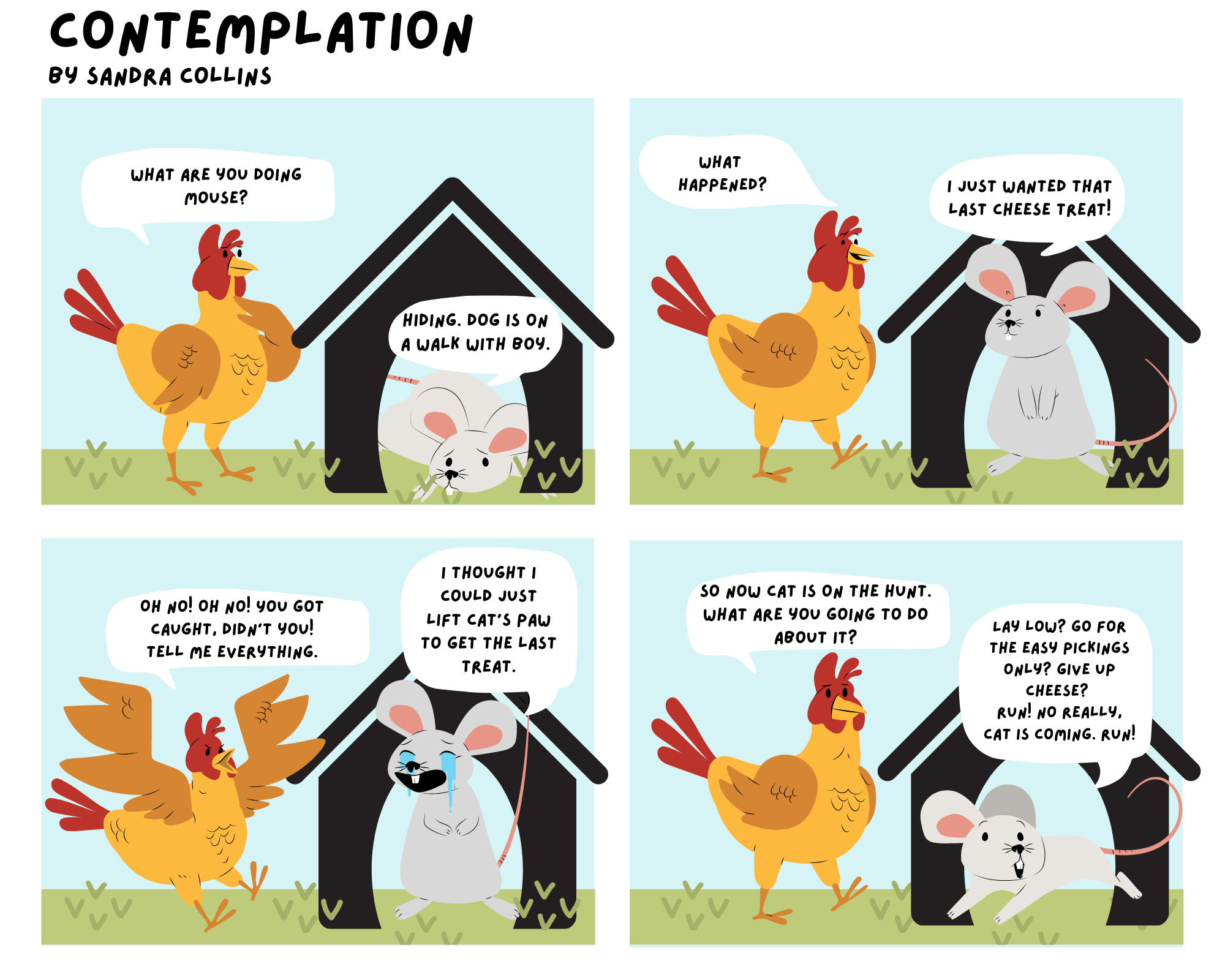

Clients in the contemplation stage know that they are facing a challenge in their lives, but they are still trying to figure out what, if anything, they would like to do about it. Krebs et al. (2018) suggested that the counsellor position themselves as “Socratic teacher” (p. 1969) in this phase. Socratic conversations with clients involve purposeful, but open-ended dialogue to encourage their reflection and increased awareness. In most cases, these conversations invite them in small, incremental steps to critique and dismantle barriers to change in their thoughts, feelings, behaviours, and relationships.

- During the contemplation stage, clients will benefit from the relational concepts, principles, and practices associated with a multidimensional exploration of the challenges (Chapters 4 to 7). Identify those that may support clients to deepen their understanding of the challenges they face to support movement from contemplation to preparation.

- These processes support clients to build incrementally a more complete self-understanding of the nature of the challenge and the ways in which it influences their thoughts, feelings, behaviours, and relationships.

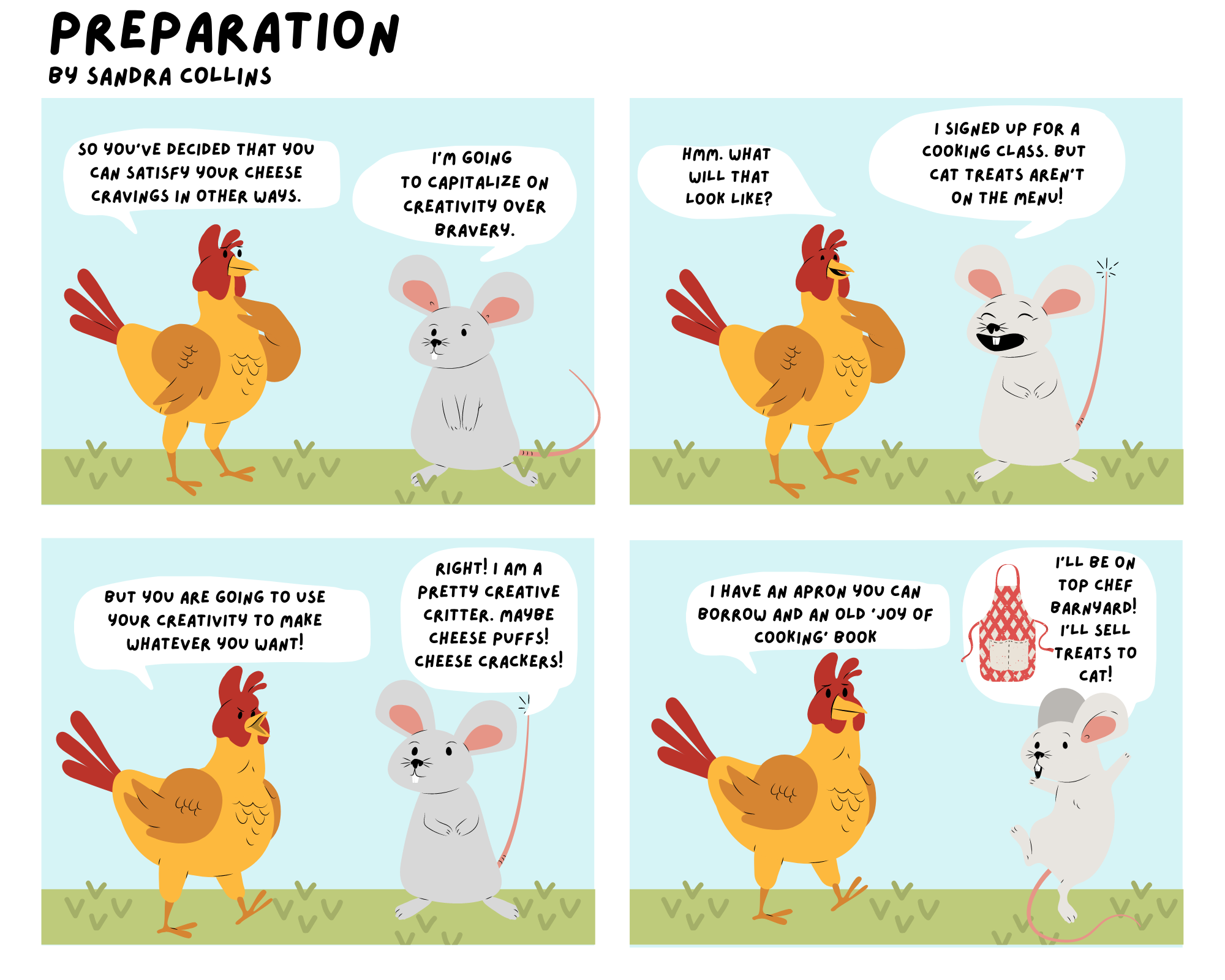

As clients move into the preparation stage, they shift from meaning-making about the challenge they face to envisioning their preferences (i.e., how they would like their lived experiences to be different) (Chapters 8 and 9). They may have begun to take small steps towards change, but they can require additional support to be fully prepared to embrace that change.

-

- How might the process of envisioning and thickening descriptions of client preferences encourage clients to move from contemplation to preparation?

- Krebs et al. (2018) position the client–counsellor relationship at this stage as one of coaching, in which the counsellor can draw on their experience to work with the client to co-construction a “game plan” (p. 1969) to support change.

- In this chapter we focus primarily on the preparation stage. We build on the model for conceptualizing client lived experiences to begin to set therapeutic directions with clients.

Stages of change, client worldview, and systemic factors

As we continue to apply a critical lens and to adapt various counselling processes to be culturally responsive and socially just, consider the following questions for reflections on the stages of change:

- This model has a particular worldview: Which assumptions are inherent in the stages of change model?

- Where is the locus of responsibility and control for change typically placed?

- To what degree are client views of health and healing or social locations considered?

- How might the stages of change apply to challenges located with the sociocultural contexts of client lives?

- How might this model be adapted to be responsive to each client?

- The model focuses on behavioural change on the part of the client. What other domains of change might need to be considered?

- The model focuses on self-efficacy and individual motivation for change. How can the barriers and supports clients encounter in family, community, institutional, sociocultural, or broader economic and political systems be integrated and considered?

One of the limitations of the study by Krebs et al. (2018) is that most of the published studies available for their meta-analysis focused on addictions and other health behaviours, which then tended to be approached from a narrower, individualist perspective compared to the broad range of challenges faced by clients in counselling. Krebs and colleagues asserted the generalizability of the stages of change; however, they recognized that the narrow focus on behaviour change reflected a eurowestern worldview of health and healing.

Locus of Control and Responsibility

The transtheoretical stages of change model is also grounded in a eurowestern definition of locus of control defined by the clients’ subjective assessment of whether the outcomes they desire are within their control (i.e., internal locus of control) or are determined by other people or conditions (i.e., external locus of control). What is important in this definition is the word “subjective.” It is assumed that the client has a choice in how they view the circumstances they encounter, without considering that there are times when external factors (e.g., colonization, patriarchal systems, and other social determinants of health) are actually, not just subjectively, outside of the client’s control. Empowering clients and enhancing their sense of agency over their lived experiences can be critical to their readiness for change. To support client agency and readiness for change, Collins (2018a) challenged counsellors to consider broadening the locus of control and responsibility for change as part of the process of conceptualizing client lived experiences.

Deconstructing locus of control and responsibility

Consider the limitations of applying a more traditional, individualist view of locus of control as illustrated in the final comic.

Draw on the process of deconstruction from Chapter 9 to apply a contextualized, systemic lens to the barnyard dilemma. Attend to both sociocultural contexts and dominant or nondominant discourses. To broaden perspectives on locus of control, it may be important to ask some of these questions:

- How might the experiences of mouse and cat differ from each other based on disparities within the barnyard hierarchy?

- How might cat be differently advantaged as it seeks out new opportunities to meet its needs?

- In what ways might mouse be more likely to be positioned in other contexts as more personally responsible for not being successful at meeting its needs?

- How might these inequities influence both mouse’s sense of locus of control and its readiness for change?

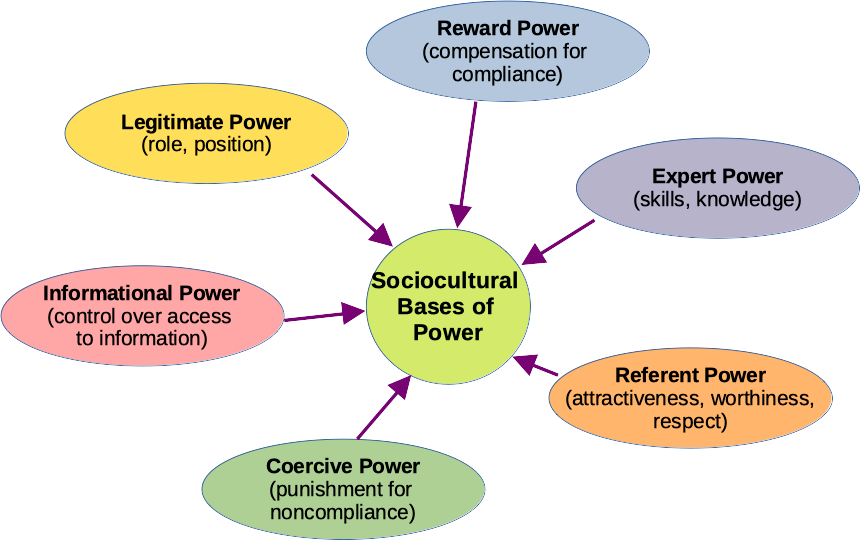

- How might cat’s access to various forms of power differ from that of mouse and rooster?

- In what ways might this differential access to power affect readiness for change and the capacity for setting specific directions for the change process?

The Sociocultural Bases of Power image above is from Culturally Responsive and Socially Just Counselling: Teaching and Learning Guide, by Collins, 2018, Counselling Concepts (https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc16/#agereligion). CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

In Chapters 8 and 9, we positioned both client challenges and preferences within their cultural identities, worldviews, and the sociocultural contexts of their lived experiences. Responsive application of the stages of change model requires care-filled and careful attention to the weight of responsibility assigned to the individual versus the environment (Collins, 2018a; Ratts et al., 2015, 2016). Krebs et al. (2018) emphasized the importance of attending carefully to client positioning within the stages of change and to matching counsellor relational practices and therapeutic approaches to the client’s readiness for change. In some cases, this can mean supporting clients, particularly in the contemplation and preparation stages of change, to externalize the challenge and to deconstruct the ways in which the challenge may be located within dominant or nondominant sociocultural contexts and narratives.

COUNSELLING PROCESSES

A. Establishing Therapeutic Directions

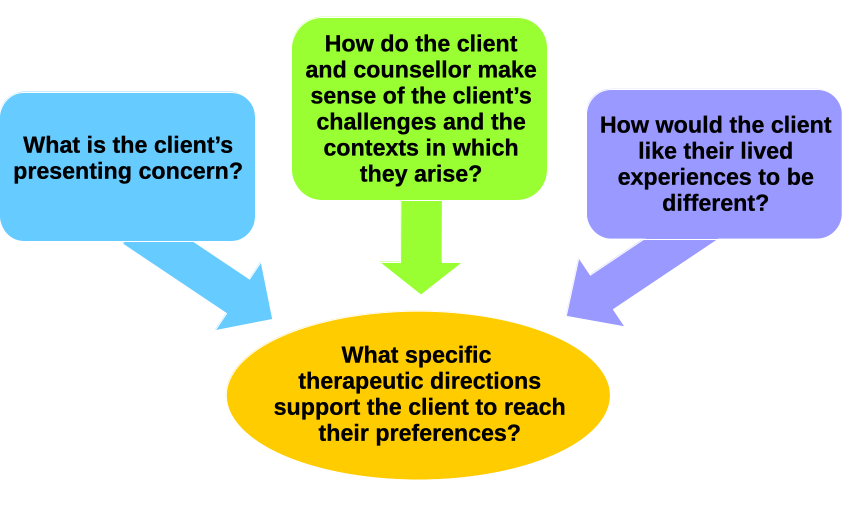

The image in Figure 2 has provided a conceptual framework for the process of conceptualizing client lived experiences throughout this ebook. You have now worked through the process of assessing the client’s presenting concern, collaborating to co-construct a shared understanding of the challenge they face and the contexts in which it arises, and examining with them how they would like their lived experiences to be different. In this chapter we move on to the final question at the bottom of the figure: What specific therapeutic directions support the client to reach their preferences? The process of establishing therapeutic directions involves getting a clearer sense of how the client views health, healing, and change. It includes co-constructing both language and processes to provide a meaningful direction for continuing to work together toward their preferred present or future.

Figure 2

Culturally Responsive and Social Just Conceptualization of Client Lived Experiences

The process of establishing therapeutic directions is most often associated with goal-setting. Norcross and Wampold (2018) identified goal consensus as one element of the therapeutic relationship that demonstrated clear evidence of effectiveness in supporting therapeutic outcomes. Paré (2013) defined a counselling goal as “an achievable step, a milestone along the road, something a client can do to move closer to their preferred outcomes” (p. 270). However, linking therapeutic directions exclusively to goal-setting is neither representative of all models of counselling, nor is it necessarily reflective of the ways in which some clients think about healing or change processes. For example, feminist therapists may not use the more prescriptive language of counselling goals, focusing instead on laying a foundation for change through fostering client agency and empowerment (Brown, 2010). Indigenous therapists working with Indigenous clients may choose to engage in ceremony as a foundation for healing. Fellner (2018) described the nature of ceremony in the context of counselling as follows:

Each ceremony begins with preparation. I’ve been taught that preparing for ceremony is at least as important as the ceremony itself. Similarly, proper preparation for our work with Indigenous clients is essential. Once we have prepared, we may step into the sacred space and open the ceremony. Here, we meet our client and work to create a therapeutic environment and healing relationship. We then flow into the heart of the ceremony, the healing and transformation through the work itself. From there, we close the ceremony and move forward with a greater sense of knowing and wellness. We are then able to reflect and share our growth with others. (p. 183)

In the same way that we deconstructed the stages of change above, it is important to cast a critical lens on dominant discourses related to growth and change. The language used in setting therapeutic directions with clients should be responsive to client cultural identities and the ways in which they make meaning within their particular worldview of concepts like time, space, change, and healing.

Contributed by Anita Girvan (in conversation with Sandra Collins)

In this video Anita talks about the embeddedness in eurowestern and colonial worldviews of certain metaphors related to change. The language of goal-setting is one of those eurocentric metaphors. Notice the challenge of stepping outside of colonial perspectives to create space for other ways of envisioning therapeutic directions that don’t fit a linear worldview. Pay attention to the ways in which Anita and Sandra engage in a process of co-constructing meaning within this conversation.

© Anita Girvan (2021, May 24)

Questions for reflection:

- What metaphors help to organize disciplines of counselling and psychology as well as counselling communities of practice? Explore the strengths and limits of one or more of these central organizing metaphors?

- Metaphors often indicate some kind of movement in moments of novelty or change. How might they function in this way as people seek way-finding tools? What possibilities open up with the new language of way-making introduced into the conversation by Sandra?

- As you consider your own learning or professional journey and reflect upon your life, how have you have arrived at your current moment or place, and which primary metaphors do you use to describe this “journey,” “path,” or whatever.

- What role is there for co-constructing meaningful metaphors in any given counsellor–client relationship? Consider, for example, the strengths and limits of the metaphor of goal-setting that incorporates a linear time frame that may or may not be similarly useful for clients and counsellors.

- Anita introduced the word “pivot” as an alternative metaphor for change in-the-moment. What other metaphors can you generate as starting places for meaning-making around therapeutic directions?

Envisioning change without the use of verbal metaphors

Contributed by Anita Girvan (in conversation with Sandra Collins)

In this second video Anita dialogues with Sandra about ways of talking about therapeutic directions for change that move outside of verbal communication or metaphorical language.

© Anita Girvan (2021, May 24)

Questions and prompts for reflection:

- Metaphors aren’t the only tools for indicating movement. If counsellors or clients lean toward arts-based practices, as do many in IBPOC communities, how can relationships move beyond words and metaphors to generate other ways of moving in healthy ways?

- Consider the client whose story Sandra shared at the beginning of the chapter. How might a more traditional process of goal-setting have posed a barrier rather than a support for change?

- How might you draw on the microskills and techniques you have learned in Chapters 2 through 8 to support generative conversations with clients focused on shared meaning-making related to change?

In the process of setting therapeutic directions, counsellors may draw on practice experience, their personal and professional meanings associated with change, and their knowledge of the counselling process. However, this language should be offered with a tentativeness that invites forward client worldviews and lived experiences and actively engages clients in evaluating the goodness-of-fit and continuing to co-construct appropriate metaphors for change (Collins, 2018a; Paré, 2013; Paré & Sutherland, 2016; Scheel et al., 2018). We will return to the discussion of change metaphors in the section on Microskills and Techniques.

B. Progress Monitoring

In addition to setting therapeutic directions with clients, it is also important to engage in progress monitoring, which essentially answers two questions:

- How will you know that you and the client are on the path to meet their needs and preferences?

- How will you know when you have reached the point in the path when your work together is complete?

The process of both inviting and providing feedback from and to clients was identified as one of the relational practices that supports the efficacy of therapy by Norcross and Wampold (2018). Similarly, Parrow and colleagues (2019) listed progress monitoring as one of the eight evidence-based effective relationship factors in their research. In their practice recommendations Norcross and Wampold (2018) concluded:

Practitioners are encouraged to routinely monitor patients’ satisfaction with the therapy relationship, comfort with responsiveness efforts, and response to treatment. Such monitoring leads to increased opportunities to re-establish collaboration, improve the relationship, modify technical strategies, and investigate factors external to therapy that may be hindering its effects. (p. 1897)

1. Engaging in Routine Outcomes Monitoring

Progress monitoring involves checking in regularly with clients about the client–counsellor relationship, therapeutic directions, and the processes that counsellors and clients engage in together. It involves centring clients as the experts in their lived experiences and inviting them to be transparent about their expectations and engaged in evaluating the degree to which these expectations are being met (Parrow et al., 2019). Simon Nuttgens has prepared an overview of routine outcomes monitoring to guide you in this area.

A primer on routine outcome monitoring

Contributed by Simon Nuttgens

What is routine outcome monitoring?

Routine outcome monitoring (ROM) is a generic term used to describe the use of standardized self-report measures to collect various types of client information. Typically, counsellors and psychologists collect client self-reports of progress toward goals, symptoms and functioning, and the strength of the client–counsellor relationship. ROM is used for a variety of purposes including documenting the effectiveness of agency services, generating research data, and improving counsellor effectiveness.

How is routine outcome monitoring implemented?

ROM can be used at various practice intervals. Some ROM measures are used session-by-session and, hence, are often referred to as progress monitoring. Other assessments are used at longer intervals or pre-post service delivery. Traditionally, ROM assessments were administered using paper and pencil; however, electronic alternatives are increasingly being used (i.e., via apps and tablets). Most ROM measures are designed for use by all counsellors regardless of theoretical orientation or type of practice (i.e., individual, couple, family).

How can routine outcome monitoring help me in my practice?

There are three primary ways that ROM can help improve outcomes. First, it can be used to track the strength of the client–counsellor relationship and to make corrections should the alliance falter. Evidence clearly indicates a strong correlation between the strength of the working alliance and a successful therapeutic outcome. The ability to track and modify the strength of the alliance helps the counsellor adjust their approach to prevent alliance ruptures from occurring. Second, ROM can be used to monitor client change and adjust interventions to optimize changes processes. Third, ROM can be used to identify clients who are responding poorly to counselling and are at risk of dropping out. This is especially important given that counsellors often struggle to identify clients who are not benefitting from counselling (Walfish et al., 2012).

What are some common routine outcome monitoring measurement tools?

There are many ROM measurement tools to choose from, each with accompanying strengths and weaknesses. Common ROM tools include: the ORS and SRS developed by Scott Miller and colleagues; the OQ 45, developed by Michael Lambert and colleagues; and CORE, developed by Michael Barkham and colleagues. The various ROM measures differ in cost, administration time, and language offerings. Fortunately some assessments, such as the ORS and SRS, include free versions. For further reading: Overington and Ionita (2012) provide an excellent overview of the various ROM systems.

How can I maximize the effectiveness of routine outcome monitoring?

As with any counselling skill, maximizing the effectiveness of ROM involves dedication, practice, knowledge, and sound judgment. There are additional things, however, that you can do to increase the likelihood of successful implementation. Here are a few tips.

- Take time to research which ROM tool fits best with your approach to counselling, your typical clientele, and your practice context (i.e., agency, private practice). For example, you might find that a ROM measure that can be administered quickly works well for agency work where you have a large caseload and a high number of younger clients.

- Be sure to explain to your clients during the informed consent process why you use ROM and how it can benefit them. Not doing so may lead clients to view ROM as just another type of administrative paperwork, unrelated to the counselling process and its outcome.

- Seek supervision from a supervisor who has training and experience using ROM. Counsellors sometimes begin using ROM only to give it up quickly because they feel stuck, unsupported, or both. In these instances, supervision can provide the guidance and encouragement necessary to push past the initial challenges.

- Realize that ROM may not be appropriate for all clients. For example, clients who are motivated to deceive, who are experiencing psychosis, or who struggle with reading may not respond well to ROM (Ionita et al., 2020). In general, it is important to exercise sound clinical judgment when the suitability of what you are doing with a client is uncertain.

- Adjust the ROM to fit with your clientele, your preferences, and your specific practice context. This advice is offered tentatively, with the caveat that ROM measures are standardized and tested according to specific practice parameters. Altering these may decrease the effectiveness of a ROM measure because it no longer conforms to the original research conditions. However, there is reason to believe that counsellors are better off gathering some client feedback rather than none, and that rigid adherence to any counselling practice will undermine its effectiveness.

What don’t we know about routine outcome monitoring?

Although we know that ROM can help facilitate a positive therapeutic outcome, we still don’t know how it works. Does it work because (a) clients are more focused on goals, (b) counsellors are more attuned to negative feedback, or (c) the instrument triggered a placebo effect? Research that points to the mechanisms of change is still needed. We also have a limited understanding of moderators and mediators. Said another way, we do not have a granular understanding of what types of ROM work best for whom and under what conditions. This lack of understanding is most salient in terms of cultural diversity, which has not yet been a focus of ROM research.

As Simon noted, ROM development and research has not paid attention to client cultural identities and social locations, which leaves a significant gap in terms of its application across diverse cultural groups. Soto and colleagues (2018) noted the importance of adding questions about counsellor cultural competence to ROM processes. They argued that this is particularly important because their research suggested that therapist self-assessment of multicultural competence had little relationship to therapeutic outcomes, whereas client ratings of therapist cultural competence were significant. Any time you choose to use standardized assessment processes, it is important to reflect critically on the research, noting particularly the population for which the tool was developed and normed. Attend carefully to the justifiable hesitancy of some clients to trust in more formal healthcare assessment processes, and have an open and honest conversation with your clients about how to best meet their needs through the process of routinely enlisting their feedback in ways that fit for them.

2. Embracing Between-Session Change

Prochaska and Norcross (2018) described how extratherapeutic factors such as a new job, new relationship, relocation, or loss of a family member can play a significant role in how clients experience therapy. You have followed the story of Macey across chapters. We deliberately left the counsellor out of this story so that you could imagine yourself in that role. Macey’s story also serves to highlight how much change happens between sessions without the active involvement of the therapist. This should be a humbling observation if you are inclined towards feeling indispensable. Paré (2013) argued that change is the one thing that does not change. It behooves us as counsellors to pay careful attention to these between-session changes as we work with clients to conceptualize their lived experiences and to set therapeutic directions. Optimizing between-session change may require being purposeful in working with clients to co-construct specific activities or to access to particular resources. Even small shifts in patterns between sessions can have significant outcomes. In the textbox below, Gina reflects on the significance of between-session change and offers some suggestions about how to navigate what may seem like progress or regress from session to session.

Each time a client returns to counselling, it seems like I am catching up on the next chapter of their story. They have lived their life outside of my office space, and it is important for me to invite them to share how the last week (or last two weeks or last month) has been. There is no formula for how often or how long one needs to be in therapy, and it could depend on the illness or wellness models of health (Howes, 2014). Howes (2014) noted that the illness model is akin to seeing a physician to lessen unpleasant symptoms and the wellness model is akin to joining a gym to improve one’s life and attain one’s potential. It could be that clients may want to start with once a week or once every two weeks and go from there.

Between each session, clients may reflect on the session and immerse themselves on tasks co-created as homework in the previous session. What I have learned is that sometimes clients report progress and at times they report more pain and struggles. It is not unusual for clients to feel worse a few days after the first session, due to having poured out difficult feelings; some then reflect on that emotional sharing over the next few days. Some of my clients let me know that during and right after the session, they feel lighter and have more hope. However, when they return to their real life and need to navigate work, family obligations, isolation (and more), they can experience a range of negative emotions. Often, I begin subsequent sessions with a question focused on between-session change:

- How was your week?

- Is there anything we talked about the last session you would like to revisit?

- What would you like to focus on today?

I find that continuing the conversation from where we left it and asking clients what is most important to work on is client-centred. However, some clients pass the ball back to me and indicate they want me to direct the session, which I am glad to do.

Gina

Reflections on between-session change

- If you have been a client, what did your counsellor say or do at the beginning of your sessions that helped structure the session?

- If you have been a client, how regularly did your counsellor ask about your perceptions of the previous session or what has happened for you in the time between sessions?

- If you have been a client, were you regularly invited to share what you would like to focus on?

- If you answered yes to some or all of these question, what was helpful (or not) about this way of questioning?

- If you have not engaged in therapy yourself, how would you envision your preferences for counsellor check-ins with you in each session?

MICROSKILLS AND TECHNIQUES

The Responsive Microskills and Techniques summary provides a quick reference to each of the techniques introduced in this chapter.

A. Responsive Techniques

1. Exploring Client Readiness

Before moving into setting therapeutic directions with clients, it is important to explore their readiness for change. As noted earlier in the chapter, this may include assessing, directly or indirectly, where they current sit in terms of the stages of change: precontemplation, contemplation, or preparation. In some cases, it might also be important to assess the locus of control for change to avoid engaging in unintentional cultural oppression by sending the message to the client that they should adapt to, or cope with, external, contextual, or systemic factors that negatively affect their health and well-being. Exploring readiness for change often involves attending carefully to between-session changes that can signal client preparation to move forward with setting therapeutic directions.

| Description | Purpose | Examples |

|

|

|

The following videos provide examples of exploring client readiness. Both of these videos locate the challenge either within in the individual or within their immediate interpersonal relationships.

Exploring client readiness: Expectancy of, and preparation for, change

Featuring Sandra Collins and Gina Ko

In previous videos (Chapters 7 to 9) Gina talked about her preference to see herself as “good enough” in various spheres of her life. In this video Sandra focuses in on the stages of change introduced in this chapter that support client readiness for change. Notice how Sandra uses transparency to invite Gina into a conversation about her readiness for change. Sandra then summarizes where she perceives Gina to be in terms the first two stages and invites Gina to deepen (thicken) her preparation for change.

- Precontemplation: Gina has clearly identified that there is a challenge—the lack of balance—that is negatively affecting her health and well-being.

- Contemplation: She also has a general sense of what she would like to do about it—focus on being good enough in various domains of her life.

- Preparation: Gina has begun to shift from meaning-making about the challenge to envisioning her preferences (i.e., how she would like her lived experiences to be different) by identifying ways in which she is already good enough in certain areas. Sandra reinforces this shift at the beginning of this video. Then Sandra invites Gina to consider those moments when the imbalance reappears.

We do not label the microskills in the videos in this chapter. This gives you a chance to view the videos without interruption and to identify the various microskills yourself.

© Sandra Collins & Gina Ko (2023, June 6)

Reflections:

- What specific microskills did Sandra use to foster expectancy and readiness for change?

- How did Sandra support Gina to prepare for, and anticipate, change?

- How did exploring between-session change influence the conversation? What might have happened if Gina’s between-session experiences had been ignored?

- In what ways did Sandra shine a light on Gina’s sense of agency and self-efficacy?

- What external supports for change came into view?

- In what ways might Gina be more prepared by the end of this short conversation to move toward change?

Exploring client readiness: Preparing for change and amplifying client agency

Featuring Gina Ko and Sandra Collins

Sandra’s preferences, from the videos in previous chapters, centre around bringing her whole self into all areas of her life. In this video Gina begins to explore readiness for change with Sandra by examining how broader sociocultural contexts hold both supports and barriers to more public mind–body–spirit–heart integration. Gina watches for opportunities to reinforce Sandra’s sense of agency and empowerment in the face of these barriers.

© Gina Ko & Sandra Collins (2023, June 6)

Reflections:

- How does Gina invite Sandra to reflect on the both/and of barriers and supports for change?

- How does Sandra assess her locus of control over various situations as part of her decision-making around investing in change?

- How does Gina empower Sandra to enhance her readiness for change?

As you can see from the three videos above, the process of exploring client readiness leads logically toward more focused conversations on setting therapeutic directions.

2. Way-Making: Envisioning Change

For the remaining techniques in this chapter, we consider how to invite clients to envision what we have chosen to label as way-making. We chose this term as a broader umbrella concept for setting therapeutic directions with clients. The process of way-making is inclusive of eurowestern processes of goal-setting, but it also opens the door to conversations with clients about other ways of conceptualizing movement and direction within counselling that are a better fit for clients whose worldviews foreground, for example, relationality, interconnectedness across time and space, or circular rather than linear perspectives.

Glimpses into ways of thinking about change

The audio conversations below to illustrate the ways in which cultural inquiry may be applied to way-making. We chose audio to avoid the potential bias of assigning particular beliefs and values based on visible markers of difference. The voices of counsellor and client have North American accents. This is also a deliberate choice to not characterize worldviews by external characteristics. Worldviews are influenced by factors beyond cultural heritage, and personal views of health and healing can change and evolve over time.

As you listen to each of these audio dialogues between counsellor and client, attend to the ways in which the counsellor introduces conversations about change (sometimes following a misstep). Attend carefully to the clues to client worldviews in the conversation, and reflect on how this lens affects their views of change.

Click here for a transcript of these audio conversations.

Questions for reflection:

- In these audio conversations, the clients provide glimpses into their values and assumptions about relationality, decision-making processes, relationship to time, perspectives on change, inclinations towards being versus doing, and so on. How do these perspectives fit or not fit with your worldview?

- How might you build continual check-ins into your conversations with clients to ensure that you are not imposing assumptions about counselling processes that derive from your worldview?

- How comfortable are you with framing therapeutic directions from within a client’s idiosyncratic or culturally embedded view of change?

Consider the following possibilities for how you might move into way-making with the clients whose voices you heard in the three audio clips above.

- Identify the people who may be involved in determining how the process of change unfolds.

- Assess how client worldview might influence how counsellor and client know when the counselling process has served the client’s needs and intentions.

- Explore the contexts in which way-making can play out and what the influence of those contexts might be.

- Thicken metaphors for change to guide your work together.

- Co-construct markers of progress or change—however progress or change is defined—for which both client and counsellor can watch as they work together.

For each of these clients, the process of setting therapeutic directions may diverge from, or require modification of, the process of goal-setting. Applying techniques that are clearly embedded in eurowestern worldviews without critical examination of the underlying assumptions with clients is a form of psycholonization. Keep in mind how and when you can engage clients in critical assessment of the goodness-of-fit for them. A summary of the technique of envisioning change is provided below.

| Description | Purpose | Examples |

|

|

|

Envisioning change: Personal views of change

Featuring Sandra Collins and Gina Ko

In this video Sandra invites Gina to talk about the meaning of change for her from a personal perspective and from a cultural perspective. Notice how Sandra draws forward the collectivist worldview that Gina introduce when she was talking about the meaning of good enough in an earlier video.

© Sandra Collins & Gina Ko (2023, June 6)

Reflections:

- How does this conversation about the meaning of change support Gina’s readiness for change?

- If you were working with Gina, what other aspects of change might you explore to more fully understand her perspective and sociocultural context?

- What might the consequences be for the client–counsellor relationship if the counsellor simply assumes that all clients view change in the way the counsellor views change?

3. Way-Making: Narrowing the Focus

If you have explicitly explored multiple domains of lived experience with the client, you may want to invite them to narrow their focus to one or two areas as a starting place for change. In some cases this might mean choosing between thoughts and feelings. In other cases clients might choose a particular realm of their lived experience: family, work, community. Others may focus on the particular roles they play in relationship. The intent is simply to take the big picture of how clients would like things to be different and to invite them to attend to one or two manageable starting places. Change is fluid, unpredictable, and multidimensional. There is no right starting place, and change will likely ripple into other areas of clients’ lives. There are many reasons for choosing a particular starting place, which are unique to each client and the contexts of their lived experiences. You may want to invite them to consider:

- What is most relevant or pressing?

- What is more important or meaningful?

- What is the easiest or least stress-inducing?

- What will be more rewarding?

- And so on.

| Description | Purpose | Examples |

|

|

|

Way-making: Narrowing the focus

Featuring Gina Ko and Sandra Collins

Gina and Sandra have discussed a number of areas of Sandra’s life where she would like to bring forward her whole self. To support the process of setting therapeutic directions, Gina invites Sandra to narrow down her focus by identifying a starting place for change.

© Gina Ko & Sandra Collins (2023, June 6)

Reflections:

- How does Gina reinforce expectancy for change in this conversation with Sandra?

- In what ways does Gina capitalize on between-session and past change to move them toward setting therapeutic directions and reinforcing Sandra’s readiness for change?

Is it finally time to set therapeutic directions?

Featuring Sandra Collins

You might be wondering at this point how you can possibly integrate all of learning we have presented in this ebook in your work with each client. In this short video Sandra reflects on the learning process up to this point and addresses how the various relational practices and counselling microskills and techniques are likely to play out in counselling practice.

© Sandra Collins (2023, June 6)

Way-Making: Refining Therapeutic Directions

Clients usually come to counselling because something is amiss. Things are not how they are would like them to be. This is a good starting place for goal-setting. They may express their concerns as:

- Complaints: “My son is staying out all night and stealing cars”; or “I can’t seem to find a job that suits me.”

- Statements of blame: “If my spouse was not so distant, I would feel less lonely and insecure.”

- Statements of process or means: “We need family counselling”; or “I would like to talk about my feelings about having been sexually abused.”

- Dreams: “I’d like to go back to school and become a doctor.”

- Wishes: “It would be great if I didn’t get nervous when I have to present in class.”

- Desires: “I would really like to have a better relationship with my daughter.”

- Hopes: “One day I’d like to overcome my pattern of moving from one job to another when things get a bit too demanding.”

The process of co-constructing a shared understanding of client challenges and preferences lays a foundation for setting therapeutic directions. However, many clients will benefit from further refining therapeutic directions. You have probably noticed that, even though we are not explicitly focusing on change processes in this ebook, change is already happening in our demonstration videos, particularly in the conversations between Sandra and Gina in the last couple of chapters. Many clients begin to experience positive change simply by virtue of being welcomed into relationship. The process of deconstructing a client’s preferences for how they would like things to be different can often lead to further change as they initiate movement toward those preferences.

| Description | Purpose | Examples |

|

|

|

Refining therapeutic directions: A holistic approach

With Gina Ko and Sandra Collins

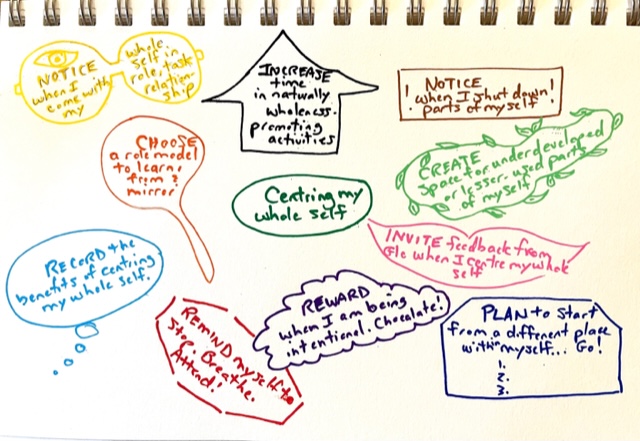

Sandra has stated that she wants to centre her whole self in more areas of her life. After the last video, Gina asked Sandra to list specific ideas about how she might begin to invite change. In working through this homework assignment, Sandra realized that it was an opportunity to practice a wholeness approach. So, instead of making a list of incremental goals, she generated an image of possible ways in which she might begin to move towards her preference for change (see below).

Gina now invites Sandra to debrief this exercise and to explain her choices, both in terms of content and process.

© Gina Ko & Sandra Collins (2023, June 14)

If you have watched most of the videos in this ebook, you will probably realize that setting these intentions may not be fully effective in supporting Sandra to show up with her whole self in all areas of her life, because this has been a struggle for a long period of time. However, by breaking her intention down into these more manageable pieces, Sandra will likely gain insight into what else is required to support lasting change.

Practice activity

- Articulate a current challenge you are facing as well as your preferences for how you would like your lived experiences to be different. You may want to draw on your story that has evolved from chapter to chapter as part of the reflective practice process.

- Consider how you envision change and identify 2–3 meaningful processes of way-making that might support you to refine a sense of therapeutic direction. Focus on generating processes that are unique to you, reflect your way of being in the world, or draw on your cultural identities.

- Play around with a couple of these options to see how they work for moving from a broad sense of how you would like things to be different to a more refined sense of therapeutic direction.

- What do you learn from this activity to support client-centre and culturally responsive work with clients?

For some clients who relate to, and benefit from, a step-by-step, incremental process of change, it may be important to define and refine goals and subgoals as both guides for change and markers of progress. One of the common tools to support goal-setting with clients is referred to as SMART goals. SMART is an acronym for five characteristics that help you set well-defined goals. Very seldom do clients enter counselling with clearly defined, behaviourally specific, measurable goals.

Setting therapeutic directions: Developing SMART goals

Contributed by Don Zeman

Process for developing SMART goals

Let’s say your goal is: To improve my ability to implement a particular counselling skill.

How do we measure that? When do we measure it? Think about the outcome you are seeking. Remember a goal is something you want to change or improve. Consider the SMART criteria below:

- Specific: A particular counselling skill that you have already been working on improving.

- Measurable: On a self-report scale of 1/10 to 10/10.

- Achievable: How realistic or attainable is this?

- Relevant: Improving my skills is definitely relevant for me as I become a counsellor.

- Time-framed: What’s a reasonable date for achieving this goal? I will complete this goal within X days.

Example

Original Goal: To improve my ability to be culturally responsive and utilize the client’s cultural lens.

- Specific: I will improve my ability to be culturally responsive and utilize the client’s cultural lens in my counselling skills course.

- Measurable: On a self-report measure using a scale of 1 – not well done to 10 – as good as I can imagine possible during online and classroom parts of this course, I will improve from a rating of X/10, today (May 15), to X + Y/10 (e.g., from 5/10 to 7/10).

- Achievable: This is attainable and realistic because I have already improved from a 1/10, at the start of this course, in both understanding of and ability to be culturally responsive and utilize the client’s cultural lens to 5/10 today (May 15).

- Relevant: This is a very relevant skill for me to have as a counsellor.

- Time-framed: I will improve from X/10 to X + Y/10 by July 23.

To create your revised goal, combine the S, M, and T together to form a succinct goal statement: “I will improve my ability to be culturally responsive and utilize the client’s cultural lens from my current level of 5/10 to 7/10 by July 23.

Practice activity

Choose either your own story that has evolved from chapter to chapter or the story of Macey. Drawing on what you know at this point of your (or her) preferences, identify three possible goals that fit the SMART goal criteria. Remember, this would normally happen in consultation and collaboration with the client. So feel free to take some creative license in making up these goals if you choose Macey’s story as a starting place. What is important is for you to follow the SMART criteria.

The PDF version of this exercise also includes some resources related to SMART goals.

Once you have worked with the client to set goals, it is important to break them down into a series of subgoals to make them manageable and to support incremental change.

Way-making: Refining SMART goals

Contributed by Don Zeman

Once you have created well-defined SMART goals with a client, you may need to work together to take a larger goal and break it down further into sub-goals to create a step-by-step process for attaining the overall counselling goals. You should still attend to the criteria for SMART goals in setting up sub-goals, although you don’t always need to repeat the measurement.

- Specific: A particular counselling skill that you have already been working on improving.

- Measurable: On a self-report scale of 1/10 to 10/10.

- Achievable: How realistic or attainable is this?

- Relevant: Improving my skills is definitely relevant for me as I become a counsellor.

- Time-framed: What’s a reasonable date for achieving this goal? I will complete this goal within X days.

Example

Challenge: Too insecure to speak up at work.

Preferred future: Be a more active participant in work dialogues and decision-making.

| Goal 1

I will move from a 7/10 to a 3/10 in my anxiety level in casual conversations with colleagues over the next two weeks. |

Goal 2

I will move from a 7/10 to a 3/10 in my anxiety level during formal meetings at work over the next three weeks. |

Goal 3

When I have something I want to say, I will voice my opinions in work conversations at least ½ of the time by the end of the month. |

| Subgoal

Initiate two conversations this week. |

Subgoal

Practice relaxation techniques 2–3 mornings each week. |

Subgoal

Prepare 2–3 ideas in advance of each meeting. |

| Subgoal

Communicate interest in others by asking 2–3 questions in each conversation. |

Subgoal

Use the tension in my chest as a reminder to breathe and relax during conversations (practice at least twice in each meeting). |

Subgoal

Express one of these ideas within the first half hour of the meeting. |

Practice Activity

To reinforce your understanding of this principle, revisit the SMART goals you set in Exercise 1, for yourself or for Macey, and fill in the following chart. Assume you are writing notes to evolve further goals and subgoals with the client. Be sure first to articulate clearly the challenge and preferred future. You are free to take some liberties with Macey’s story for the purposes of this activity.

Challenge:

Preferred future:

| Goal 1 | Goal 2 | Goal 3 |

| Subgoal | Subgoal | Subgoal |

| Subgoal | Subgoal | Subgoal |

Click here for the PDF version of this exercise.

Reflecting on our client–counsellor interactions

Featuring Gina Ko and Sandra Collins

Sandra and Gina have carried forward several different therapeutic conversations across various chapters in this ebook, some from 2021 and some from 2023. In this short video they debrief their experiences of working together, learning from each other, and demonstrating the microskills and techniques introduced in this ebook.

© Sandra Collins & Gina Ko (2023, June 14)

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE

1. Honouring Worldviews

We have argued that all counselling is multicultural in nature. Even when the person sitting in front of you seems to look like you or sound like you, there will always be ways in which they think differently or experience life in unique and culturally embedded ways. In this sense building responsive relationships and engaging collaboratively in the counselling processes always involves a meeting of worldviews. Throughout the activities in this ebook we have encouraged both

- an awareness of the diversity and uniqueness of each client’s perspectives on the challenges they face, what they envision for their preferred futures (or present), and how they conceptualize health, healing, and change; and

- an attention to your unique and culturally embedded lens on each of these elements of conceptualizing client lived experiences.

As you continue your own reflective practice this week, take the time to analyze critically how your worldview influences your response to the question: What specific therapeutic directions support the client to reach their preferences? Consider specifically the following questions:

- What do you believe about change within, or outside of, the counselling process?

- How is this belief connected to your assumptions about time, relationality (i.e., independence vs. interdependence), decision-making, locus of control and responsibility, motivation and readiness for change, and other concepts or principles that stood out for you in this chapter?

- How have these elements of your worldview been expressed though your approach to change in the past? To what degree have you been conscious of them as the influences of your worldview, rather than as universal truths about change?

2. Enlisting Your Own Story

As you continue to apply your learning to your own story, we invite you to reflect on the following additional questions:

- Where do you see yourself in terms of the stages of change?

- What are the implications of your beliefs and assumptions about health and healing for your readiness for change?

- What are the implications of your worldview for how you might engage in way-making in relation to the challenge you are facing and your vision for your preferred futures (or preferred present)?

Identify and reflect on a metaphor or image for change that will support your process of way-making, or apply and adapt the elements of goal-setting that are meaningful and appropriate to your views of health and healing.

3. Engaging with Macey’s story

Macey’s story Part 10

Macey describes her process of coming to the place of preparation for change.

© Gina Ko & Yevgen Yasynskyy (2021, April 16)

Consider what you know and do not yet know of Macey worldview.

- What else might you need to know about Macey’s view of change?

- How would you invite forward Macey’s perspectives on change?

APPLIED PRACTICE ACTIVITIES

A. Responsive Techniques

Preparation

Continue to work with the challenge that you each identified in Chapter 9 so that you can build upon your preferences as you apply the techniques in this chapter. You will use the same challenge for each of the applied practice activities below. Spend at least 15 minutes each in the skills practice.

1. Warm-Up Activity: Locus of Control

(10 minutes)

Preparation

In your role as counsellor, reflect on your current understanding of the challenge and preferences that emerged from the applied practice activities in Chapter 9. Review the ways in which locus of control is conceptualized in this chapter.

- Start by sharing with each other a summary of how you perceive each other’s challenge and preferences, inviting feedback from each other.

- Then discuss the relevance of (a) your tendency as the client toward either an internal or external locus of control, and (b) the potential influence of contextual, systemic factors (i.e., social determinants of health).

- Discuss the implications of locus of control or responsibility for how you might apply the techniques in this chapter to answer the question: What specific therapeutic directions support the client to reach their preferences?

- Identify elements that may be within the client’s control and those that may require systems-level change. This context will be helpful to you as you work through the techniques below.

2. Exploring Client Readiness

(45 minutes)

Preparation

In your role as client, come prepared to talk about between-session changes, even small shifts, to support the counsellor’s skills practice. Please also come prepared to offer subtle resistance to change to give your partner an opportunity to navigate this with you in their role as counsellor.

Skills practice (15 minutes each)

- Counsellor:

- Draw on a variety of microskills to invite reflection on between session change, attending to changes that reinforce client agency and suggest movement toward their preferred futures (or present).

- Engage the client, directly or indirectly, in assessing their readiness for change, attending to the various stages of change.

- Client: Look for an opportunity to push back, withdraw, or otherwise demonstrate some form of resistance.

- Counsellor:

- Consider carefully your sense of the client’s stage of change (precontemplation, contemplation, preparation) in your response to perceived resistance.

- Choose appropriate counselling microskills to (a) meet the client where they are at, and (b) reinforce the therapeutic relationship (e.g., build rapport, express empathy, communicate nonjudgement, ensure constructive collaboration).

Reflective practice and feedback

- How did the focus on between-session change foster expectancy for change?

- How did exploring between-session change position the client to be more prepared to envision ongoing change?

- What else would have been helpful to each of you in the client roles?

3. Way-Making: Envisioning Change

(45 minutes)

Preparation

Review the first activity in the Reflective Practice section to assess critically your own views of change and how these are influenced by your worldview.

Skills practice (15 minutes each)

- Counsellor:

- Draw on whatever microskills are appropriate to move into deconstructing the client’s views of change (e.g., assumptions about time, independence vs. interdependence, decision-making processes).

- Where appropriate, invite critical reflection on dominant discourses about change.

- Client: Respond as naturally as possible.

- Counsellor:

- Look for opportunities to foreground or solicit metaphoric or visual images for way-making. Work with the client to thicken their vision for way-making.

Reflective practice and feedback

- What was it like as the client to come up with a personalized and culturally responsive image or language for way-making or change?

- How might the metaphors or visual images that emerged from these conversations be helpful in providing a sense of therapeutic direction?

4. Way-Making: Narrowing the Focus

(35 minutes)

Preparation

In your roles as counsellors, reflect on various domains (i.e., biological, psychological [thoughts, feelings, actions], social, cultural, systemic) that appear to influence the client challenge and preferred outcomes.

Skills practice (15 minutes each)

- Counsellor:

- Invite consideration of the domains of client lived experience that may be relevant to setting therapeutic directions.

- Engage the client in narrowing the focus of change to one or two domains, roles, contexts, or whatever else meaningfully sharpens the focus for change.

- Attend to opportunities to reinforce client strengths, resiliencies, and motivation for change.

Reflective practice and feedback

- Reflect back on your conversation about locus of control in the warm-up activity. How might that conversation inform the client’s choice of domain focus?

5. Way-Making: Refining Therapeutic Directions

(45 minutes)

Preparation

In your role as client, reflect on the cultural appropriateness of goal-setting as a foundation for setting therapeutic directions. If you experience this process as culturally oppressive (e.g., colonizing or pathologizing), please choose not to participate in this activity. Inform your partner in advance if possible. Instead, suggest a process for setting therapeutic directions (perhaps one that you experimented with in the practice activity that followed Gina and Sandra’s debrief of Sandra’s homework process). As the counsellor, use this client-centred approach to introduce a process for way-making that is culturally responsive. You may also want to experiment with both approaches if you have time and can create culturally safety to do so.

Skills practice (15 minutes each)

- Counsellor:

- Begin with a summary of the progress made in the previous activities toward setting therapeutic directions. Then invite the client into a conversation about meaningful and culturally responsive ways to refine therapeutic directions.

- Follow the client’s lead but provide supportive direction in moving from a broad statement of preferences to more refined (e.g., meaningful, clearer, reachable) intentions or aspirations around which change processes might be designed.

- You may end up co-constructing a process that is slightly different from what the client originally suggested. Stay open, creative, and responsive.

OR

If you choose to try out the more structured goal-setting process, please follow these steps. In your role as counsellor, review Exercises 1 and 2 related to developing and refining SMART goals. Come prepared to walk the client through the SMART goals activities. To fit this activity into a 15-minute session, focus on establishing only one goal and its subgoals.

Skills practice (15 minutes each)

- Counsellor:

- Begin with a summary of the progress made in the previous activities toward setting therapeutic directions. Then suggest a possible starting place for goal-setting, or invite the client to do so.

- Work together to move from the client’s statement of preferred futures toward a counselling goal that is more specific.

- You may find it helpful to start by brainstorming possible goals and then selecting one as your starting point.

- Attend to the SMART goals criteria as you refine that goal with the client.

- Collaborate with the client to break their goal down into manageable and incremental subgoals.

Reflective practice and feedback

- Compare and contrast your experiences of using the techniques of envisioning change and refining therapeutic directions from both counsellor and client perspectives.

- What challenges did you encounter with implementing the either the client-specific process for refining therapeutic directions or the goal-setting technique? How might you overcome those challenges?

- How might the process of refining therapeutic directions need to be adjusted based on the client’s perceived locus of control or the existence of systemic barriers to health and well-being?

REFERENCES

Brown, L. S. (2010). Feminist therapy. American Psychological Association.

Collins, S. (2018a). Collaborative Case Conceptualization: Applying a Contextualized, Systemic Lens. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 556–622). Counselling Concepts.

Collins, S. (2018b). Enhanced, interactive glossary. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 868–1086). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Cormier, S., Nurius, P. S., & Osborn, C. J. (2013). Interviewing and change strategies for helpers (7th ed.). Brooks/Cole.

Fellner, K. (2018). Therapy as Ceremony: Decolonizing and Indigenizing our practice. In N. Arthur (Ed.), Counseling in cultural context: Identity and social justice (pp. 181–201). Springer.

Howes, R. (March 31, 2014). How long is too long in psychotherapy? Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/in-therapy/201403/how-long-is-too-long-in-psychotherapy

Ionita, G., Ciquier, G., & Fitzpatrick, M. (2020). Barriers and facilitators to the use of progress-monitoring measures in psychotherapy. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 61(3), 245–256. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000205

Krebs, P., Norcross, J. C., Nicholson, J. M., & Prochaska, J. O. (2018). Stages of change and psychotherapy outcomes: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 1964–1979. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22683

Norcross, J. C., & Wampold, B. E. (2018). A new therapy for each patient: Evidence-based relationships and responsiveness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 1889–1906. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22678

Overington, L., & Ionita, G. (2012). Progress monitoring measures: A brief guide. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 53(2), 82–92. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028017

Paré, D. (2013). The practice of collaborative counseling & psychotherapy: Developing skills in culturally mindful counselling. Sage.

Paré, D., & Sutherland, O. (2016). Re-thinking best practice: Centring the client in determining what works in therapy. In N. Gazzola, M. Buchanan, O. Sutherland, & S. Nuttgens (Eds.), Handbook of Counselling and Psychotherapy in Canada (pp. 181–202). Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association.

Parrow, K. K., Sommers-Flanagan, J., Cova, J. S., & Lungu, H. (2019). Evidence-based relationship factors: A new focus for mental health counseling research, practice, and training. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 41(4), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.41.4.04

Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (2019). The transtheoretical approach. In J. C. Norcross & M. R. Goldfried (Eds.). Handbook of psychotherapy integration. Oxford series in clinical psychology (3rd ed., pp. 161–183). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/med-psych/9780190690465.001.0001

Prochaska, J., & Norcross, J. (2018). Systems of psychotherapy: A transtheoretical analysis (9th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar-McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2015). Multicultural and social justice competencies. Association for Multicultural Counseling and Development, Division of American Counselling Association: http://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/competencies/multicultural-and-social-justice-counseling-competencies.pdf?sfvrsn=14

Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar-McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2016). Multicultural and social justice counseling competencies: Guidelines for the counseling profession. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 44(1), 28–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmcd.12035

Scheel, M. J., Stabb, S. D., Cohn, T. J., Duan, C., & Sauer, E. M. (2018). Counseling psychology model training program. Counseling Psychologist, 46(1), 6–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000018755512

Soto, A., Smith, T. B., Griner, D., Domenech Rodríguez, M., & Bernal, G. (2018). Cultural adaptations and therapist multicultural competence: Two meta‐analytic reviews. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 1907–1923. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22679

Wade, A. (1997). Small acts of living: Everyday resistance to violence and other forms of oppression. Contemporary Family Therapy, 19, 23–39. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026154215299

Walfish, S., McAlister, B., O’Donnell, P., & Lambert, M. J. (2012). An investigation of self-assessment bias in mental health providers. Psycho-logical Reports, 110(2), 639–644. http://dx.doi.org/10.2466/02.07.17.PR0.110.2.639-644