7 Adolescence: 12-21 Years

Be yourself. Besides, everyone else is taken

Jay Seitz

TABLE OF CONTENTS (TOC)

- Neurodevelopmental disorders and disease

- Dynamic testing

- Learning disorders: Dyslexia, dysgraphia, and dyscalculia

- Learning how to read

- Functional illiteracy

- Autism spectrum disorders (ASD)

- Developmental motor disorders

- Tic disorders

- Traumatic brain injuries (TBI)

- Specific language impairments

- Neurotoxicants

- Genetic disorders

- Physical activity and mental health

- Peers and understanding others

- Romantic relationships and sexuality

- Identity and self-esteem

- Behavioral health

To understand typical development we must compare and contrast it with atypical development where biology may go awry and where culture and the environment may have profound consequences on human development. What follows is a conceptual dialogue between the two.

Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Neurodevelopmental Disorders and Disease

Disorders or diseases that affect the development of the brain as well as the central nervous system resulting in deficits or delays in cognition, emotion, sociality, learning, and self-control and often appear in childhood or adolescence.

1. Intellectual disability (ID) is defined as having a psychometric intelligence (IQ) under 70 as well as two (2) deficits in adaptive behaviors. Adaptive behaviors reflect an individual’s social and practical competence in meeting the demands of everyday living. So, for instance, a blind adolescent, may need to learn braille or become adept in the use of technology to overcome their limitations.

Children and adolescents with intellectual disability have higher rates of adverse health conditions such as epilepsy and neurological disorders, gastrointestinal conditions, and behavioral and psychiatric problems. And even adults also have a higher prevalence of poor social determinants of health, behavioral risk factors, depression, diabetes, and poor to fair health status.

Until the middle of the 20th century, people with intellectual disabilities were routinely excluded from public education or educated separately from typically developing children. Even now, intellectually disabled children and adolescents are often segregated in special education settings as opposed to inclusion programs in regular classrooms and report social stigma that affects their sense of self in relation to others.

As adults, they may live independently, with family members or semi-independently with significant supportive services to help them (e.g., manage their finances) or in different types of institutions (e.g., sheltered workshops, group homes) organized to support people with disabilities. Indeed, about 8% currently live in an institution or a group home.

Dynamic Testing

Dynamic testing is an interesting approach to evaluating human mental abilities. In typical fashion, conventional kinds of testing methods (e.g., intelligence or achievement) measure what you have already acquired or learned; so-called “latent” or hidden abilities. For instance, you may have studied calculus or English literature as a freshman in college and they exist as dormant abilities that can be measured on a test at some later point. For instance, the Graduate Record Examination (GRE) three years later or on an employment test after graduating from college.

Yet, the ability to learn from subsequent experience (e.g., putting your math skills to work in a financial firm or your knowledge of literature in a publishing house) doesn’t simply depend on latent skills learned at some earlier point but on mastering, applying, and reapplying those skills in actual performance situations in “real-life” circumstances. Conventional or “static” tests focus not on actual performances in real-world situations but on whatever “products” have been taught and tested for previously.

On the other hand, the learning and acquisition of new skills and new abilities are best demonstrated in developing abilities rather than abilities that have been already acquired.

Why?

Well, for one thing the capacity to learn, and learn different kinds of things, changes with age and experience. Moreover, self-esteem, personality, social intelligence, cultural and work experiences, spoken language skills, and reading abilities are constantly changing and affect one’s “learning potential.” People learn and acquire different kinds of skills (e.g., learning how to ski, trade bonds, paint or sculpt, play the flute, edit a corporate press communication, become a better partner) in different ways and at different rates of acquisition.

For instance, some people learn slowly at first, speed up in the middle stages of an acquisition of a particular skill (e.g., learning a spreadsheet program), and slow down at higher stages of learning. This is called an “S-shaped learning curve.” Other individuals have a long initial period with little consolidation of a new skill (e.g., learning to snow ski) and then suddenly and rapidly increase their skill use (“salutatory learning curve”). Others show sharp fluctuations in learning something new (e.g., starting a new job as a financial analyst) in which they may show rapid increase in some skills at the same time that they appear to be making little progress or regressing in other areas (“stepwise learning curve”).

Abilities, then, might be better tested and evaluated not as static products that have reached their final maturity but as developing forms of expertise. Which suggests a different approach to learning and education whether in the doctor’s office, clinic, classroom or the workplace.

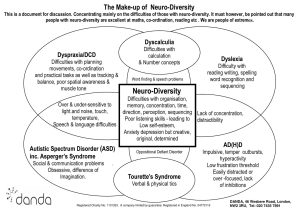

2. Learning disorders (LD) include dyslexia, dysgraphia, and dyscalculia, and students are entitled to 504 accommodations such as extra time on an exam or a quiet room.

Dyslexia can be thought of as a verbal coding deficit. The most consistent research finding is that there appear to be deficits in memory for words and the ability to segment the basic sounds of language, known as phonemes.

Dysgraphia is a deficiency in the ability to write, primarily handwriting. It is a writing disorder associated with impaired handwriting, orthographic coding–conventions for writing, including spelling, hyphenation, capitalization, word breaks, emphasis, and punctuation– and finger sequencing (the movement of muscles involved in writing).

Dyscalculia is a difficulty in learning or comprehending arithmetic such as difficulty in understanding numbers, learning how to manipulate numbers, performing mathematical calculations, and learning facts in mathematics.

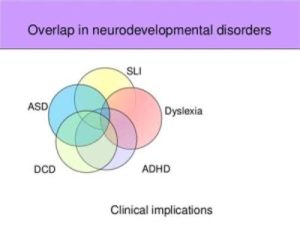

Strong scientific and medical evidence supports the validity of the concept of specific learning disabilities (SLD). SLDs are specific in the sense that these disorders each affect a relatively narrow range of academic and performance outcomes. SLD may co-occur with other disabling conditions, but they are not due primarily to other conditions, such as intellectual disability, behavioral disturbance, lack of opportunities to learn or primary sensory deficits.

Let’s look at a specific learning disability, that is, dyslexia. But first let’s step back and see how reading acquisition is normatively acquired.

The primary goal of reading acquisition is the integration of a system for processing written language with one that already exists for spoken language.

Stage 1: Linguistic guessing = helps establish the concept of what reading is.

Stage 2: Logographic phase (visual, holistic) = Early reading is visually based with children establishing the association between printed and spoken words (e.g., boy guesses the word, ‘television’ because it has two dots).

Stage 3: Alphabetic phase (auditory, sequential) = the translation between graphemes and phonemes. Children must “crack the code” and understand the relationship between graphemes (letter units) and phonemes (sound units). It may be due to the teaching of phonics or the ability of children to extract letter-sound rules for themselves or the wish to write which brings about the change since letter-sound relationships are the natural units of spelling.

Decoding skills are essential here (sequential left-to-right decoding rules, then hierarchical decoding rules, then higher-order correspondences such as lexical analogies). By the close of the alphabetic phase, children will be functionally literate, that is, they can spell with complete phonetic accuracy and adept at handling new materials both in reading and writing.

Stage 4: Orthographic phase = Reading and spelling are analytic yet independent of sound. Lexical strategies may override the use of grapheme-phoneme translation rules.

Being at one phase does not imply that knowledge characteristic of a more advanced phase is totally unavailable or that earlier strategies cannot be applied. Likewise, knowledge created by the application of one strategy can be used to check the product of that strategy’s use in some other situation.

But there are individual differences in children who use a “holistic” (visual) approach versus those who use a “Phoenician” (auditory) approach.

Both decoding strategies and the use of context (syntactic and semantic cues) are important in reading development. But there is an interaction of bottom-up and top-down approaches. One suggestion is that children use context in a compensatory manner so that when decoding skill is poor context facilitates the processing of reading material. That is, it is modulated by word familiarity and word difficulty.

What changes in development is probably the automaticity of children’s ability to access top-down or bottom-up information in reading. The research suggests that skilled readers are better at using context cues. Nonetheless, this system of interconnections improves with development. But overall, children pool information from a number of sources in their attempt to read.

Reading, therefore, is an integrative process. Stored auditory-lexical and visual information guide reading.

Literacy

Based on recent data, the literacy rate in the United States is approximately 79% of adults having English literacy skills sufficient to complete tasks that require comparing and contrasting information, paraphrasing or making low-level inferences. But that means that 21% of American adults are functionally illiterate or 21% of adults cannot read on a fourth-grade level or above.

Here are some recent statistics:

- Around 21% of U.S. adults struggle with basic reading tasks and are considered functionally illiterate. This is roughly 43 million individuals.

- But 54% of U.S. adults demonstrate literacy skills below even a 6th-grade level.

- Literacy rates also appear to be declining indicating that illiteracy is increasing.

- Moreover, the US ranks 36th in global literacy rankings.

Dyslexia

Dyslexia can be thought of as a verbal coding deficit. The most consistent research finding is that there appear to be deficits in verbal memory and phoneme segmentation. Phonemes, of course, are the basic unit of sound in speech. For instance, the ‘p’ and ‘b’ in ”pit” and ”bit”.

Studies of the serial position effect in dyslexia indicate that there are primacy effects (long-term memory) but not recency effects (short-term memory) in free recall. If dyslexics cannot access verbal labels, then they will difficulty in transferring items from short- to long-term memory, and hence, will appear to have problems in retrieval from long-term memory.

Let’s look at the serial position effect (SPE). The SPE indicates that the probability of recall varies with an item’s position on a list. The SPE is the tendency of an individual to recall the first and last items in a series best and the middle items the worst. So, when a child is asked to recall a list of items in any order (free recall), children tend to begin recall with the end of the list, recalling those items best (recency effect). Among earlier list items, the first few items are recalled more frequently than the middle ones (primacy effect). The SPE demonstrates that there are two kinds of memory: Primary memory nd secondary memory. That is, short-term or ”working memory” and long-term memory.

Research indicates that dyslexics do not use phonological codes for memory storage. Dyslexics may be delayed in their acquisition and ability to employ such codes and may be tied to learning to read. When available, they use visual or orthographic features of words as a basis of recall whereas normal readers use phonetic or phonological codes.

That is, they compensate for their deficiency by appealing to their strengths. All these results indicate that dyslexics have a specific memory deficit rather than a generalized learning difficulty.

Phoneme segmentation, the ability to divide words into single speech segments, emerges around 5 or 6 years of age. Phonemic awareness, the ability to divide words at the level of the phoneme, is thought to be an important pre-reading skill. The ability to analyze the sound stream is necessary if children are to understand the alphabetic relationship between graphemes and phonemes.

The acquisition of literacy exploits the child’s natural (and unconscious) awareness of sounds, but reading and spelling enhance the child’s conscious awareness of phonemic segments (suggesting that phonemic segmentation and awareness are both causes and effects of reading development).

Dyslexics’ difficulty is not with input or output processing, but with phoneme segmentation, phoneme awareness, and accessing and activating phonological codes in memory. Nonetheless, as dyslexics develop they make use of alternative coding systems to supplement the faulty ones. Thus, their phonemic segmentation skills and phonological memory codes are not available at the right time when they are needed for reading.

Dysgraphia

Dysgraphia should be distinguished from agraphia, which is an acquired loss of the ability to write resulting from brain injury, stroke or progressive illness.

Dysgraphia is a deficiency in the ability to write, primarily handwriting. It is a writing disorder associated with impaired handwriting, orthographic coding, and finger sequencing (the movement of muscles involved in writing). And it often overlaps with other learning disabilities such as speech impairments, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, developmental coordination disorder or dyslexia.

Nonetheless, it does affect all fine-motor skills.

There are two stages in the act of writing. The linguistic stage and the motor-expressive-praxic stage. The linguistic stage involves the encoding of auditory and visual information into symbols for letters and written words. This is mediated through the angular gyrus that provides the linguistic rules which guide writing. The motor stage is where the expression of written words or graphemes is articulated. This stage is mediated by Exner’s writing area in the frontal lobe.

Motor dysgraphia is due to deficient fine motor skills, poor dexterity, poor muscle tone, or unspecified motor clumsiness. Individuals with developmental coordination disorder may be dysgraphic.

Spatial dysgraphia is a defect in the understanding of space. They may have illegible written work, illegible copied work or problems with drawing abilities. But there is normal spelling and normal finger tapping speed suggesting that this subtype is not fine-motor based.

Dyscalculia

Dyscalculia should be distinguished from acalculia or mathematical disability, which is an acquired loss from brain injury, stroke or progressive illness.

Dyscalculia is a difficulty in learning or comprehending arithmetic such as difficulty in understanding numbers, learning how to manipulate numbers, performing mathematical calculations, and learning facts in mathematics.

Dyscalculia is associated with dysfunction in the region around the intraparietal sulcus and potentially also the frontal lobe.

Apparently, children with developmental dyscalculia may have a weak magnitude representation (e.g., estimating which number is bigger, 64 or 59) in the parietal region. Nonetheless, it may also involve an impaired ability to access and manipulate numerical quantities (e.g., Arabic digits). Dyscalculia can occur in people from across the whole IQ range, along with difficulties with time, measurement, and spatial reasoning.

Estimates of the prevalence of dyscalculia range between 3 and 6% of the population. It appears that 11% of children with dyscalculia also have ADHD. And it has also been associated with individuals who have Turner syndrome (female missing an X chromosome: 45, X0) or spina bifida (a birth defect in which there is incomplete closing of the spine and the membranes around the spinal cord).

3. Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) including include autism, Rett’s syndrome, and childhood disintegrative disorder.

Autism, a rare but devastating disorder of childhood, was originally defined by the physician, Leo Kanner, M.D., in 1943, as a constitutional inability to make emotional contact with others. More than a decade later, it was widely agreed that the two central deficits in autism were profound social impairment and insistence by the child on sameness in behavioral routines (behavioral stereotypies). Currently, the received view designates a triad of symptoms as central to the autistic syndrome: (1) social impairment, (2) deficits in verbal and nonverbal communication, and (3) behavioral stereotypies (e.g., hand-flapping, repetitive play behaviors).

Autistic spectrum disorders include autism, Rett’s syndrome, and childhood disintegrative disorder. Rett’s syndrome is typically found in very young females who despite a brief period of normal development in the first year or two of life begin to regress by avoiding social contact with others, refusing to speak, as well as evincing an inability to control their actions and behaviors. On the other hand, childhood disintegrative disorder generally only affects males who demonstrate normal development in the first 2-3 years of life but then begin to deteriorate in social, linguistic, and motor development in the ensuring years.

There are many treatment options for autistic spectrum disorders including intensive behavioral therapy, psychoactive medications, as well as some dietary and nutritional approaches.

Autism and Immunity. Recent animal research has demonstrated a connection between the immune system and autism—specifically interleukin-17 (IL-17), a signaling molecule produced by T cells to help fend off pathogens. Blocking production of IL-17 in pregnant mice prevented their pups from developing an autism-like condition.

Oxytocin and Attachment. Oxytocin, often dubbed the ‘love hormone’, is known to promote social bonding. Researchers have discovered that administering oxytocin to adult men with autism makes them more open to close emotional bonds with others. The hormone has positive long-term effects as well.

4. Developmental motor disorders including congenital injuries resulting in movement disorders leading to forms of cerebral palsy, a group of movement disorders, and neuromuscular diseases such as variants of muscular dystrophy.

5. Tic disorders including focal tics, Tourette syndrome, Sydenham’s chorea, and Huntington’s disease (juvenile).

The ability to shift from one activity (e.g., doing one’s taxes) to another (e.g., answering the phone) involves inhibiting the first activity to pursue a second activity and results in the production of new sequences of behavior. Repetitive stereotyped activities, such as obsessive-compulsive behavior and Gilles de Tourette syndrome, indicate the malfunctioning of this system.

In psychiatry, these are grouped together as OCD (“obsessive-compulsive disorder”) spectrum disorders: Gambling, paraphilia (sexual fetishes or “liking a part”), body dysmorphic disorder (e.g., thinking you’re fat when you’re thin), trichotillomania (constant hair-pulling), hypochondriasis, somatization disorder (frequent psychosomatic complaints), Gilles de Tourette syndrome (motor and vocal tics), autism, kleptomania, impulse control disorders, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, bulimia, and anorexia nervosa.

The cortex (namely, the orbitomedial frontal cortex), the subcortex (particularly a structure known as the basal ganglia), and the body work together in communion with the social and physical environment to accomplish everyday intellective tasks.

The orbitomedial frontal cortex is involved in inhibiting socially inappropriate behaviors and freeing the mind from distractions for the task at hand. The basal ganglia, located deep within the interior of the brain, dynamically modulates behavior based on feedback from the motor and affective systems and from our various external sensory modalities (touch, vision, audition, olfaction, and gustation)—the body. These two brain structures are intimately connected and cutting their nerve fibers, as it turns out, is sometimes useful with patients with refractory OCD.

Case Studies

Indeed, a malfunctioning basal ganglia leads to stereotyped movement patterns and the absence of novel behaviors. One patient I treated had obsessive thoughts that he was going to be infected with a sexually transmittable disease from casual sex (OCD) and another I observed in a clinic was a compulsive swearer (Gilles de Tourette syndrome). The first adolescent was a particularly interesting clinical case because he grew up in a home where his father was a compulsive gambler and continually stole money from his wife and two sons. As a result, the family was always broke and family finances—like mortgage, electric, and gas payments—were often unmet.

There were two brothers, who were identical twins, and both suffered from OCD. The mother was the only so-called “normal” individual in the family. It must have been quite difficult for her raising a family of compulsive gamblers and “ideators.” In both cases, the basal ganglia along with the orbitofrontal cortex, constrained the father’s and the sons’ ability to switch mental set and each one of them were mentally “stuck” in one mode or the other of responding to the world. In the case of the two twins, the actions of the first sibling led to certain thoughts (constant fear of catching a sexually transmittable disease) and the thoughts of the second led to certain actions (compulsive hand-washing).

Clomipramine (“Anafranil”), a nonselective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (NSRI), can be an effective treatment for OCD. However, about 40% of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder do not respond to either an NSRI or a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) treatment. This may be so because some forms of obsessive-compulsive behavior are a result of excessively high levels of dopamine, not serotonin.

High doses of dopaminergic drugs that increase production of dopamine in the brain (e.g., amphetamine, apomorphine, bromocriptine, and L-DOPA) appear to increase stereotypical movement and compulsive behaviors in humans in one of four dopamine pathways, the nigrostriatal pathway.

On the other hand, another dopamine pathway, the mesocortical pathway, appears to be involved with some of the “cognitive” symptoms of OCD, such as obsessive thoughts. Genetic studies suggest that these kinds of obsessive-compulsive disorders are highly heritable. As a result, it is often difficult to treat OCD individuals with supportive psychotherapy alone so treatment is often augmented with the use of psychoactive drugs.

Everyday Risk-Taking

What about everyday risk-taking? Many forms of gambling and stock speculation (e.g., investing in stock options and mortgage-backed securities), high-risk activities (such as bungee jumping, rock climbing, cave exploration, and parachuting), and similar pursuits probably arise from deep roots in human nature that are affected by culture, age (adolescence), and experience. They have many positive benefits and some negative effects and potentially lurk within all of us. To be sure, a sobering thought.

6. Traumatic brain injury (TBI) includes concussions.

A traumatic brain injury (TBI), also known as an intracranial injury, is an injury to the brain caused by an external force. It can be classified based on severity, mechanism (closed or penetrating head injury) or other features (e.g., occurring in a specific location or over a widespread area). Head injury is a broader category that may involve damage to other structures such as the scalp and skull. TBI can result in physical, cognitive, social, emotional and behavioral symptoms, and outcomes can range from complete recovery to permanent disability or death.

TBI is one of the most stressful conditions in the pediatric age group. Its symptoms affect the child as well as family. It involves neurological, psychological, and behavioral deficits in the child. But the clinical symptoms of a child with TBI depend on the site of lesion. The motor deficits include muscle weakness, facial palsy, affected posture, balance impairments, and atypical gait. The behavior of the child is also affected due to trauma and hospitalization.

Case Description

A 3-year-old girl, while playing in the corridor had her dress got stuck into the cupboard and the cupboard fell on her head and she was injured. As she fell down on her face, she started bleeding above the right eye. At that movement she was unconscious and there were no movement. Her relatives took her to the local hospital. On the way to the hospital, she had two episodes of vomiting. But due to unavailability of the necessary facilities, she was taken to a specialty hospital. During that transport, she vomited again twice. At the hospital she was immediately taken to surgery and was sutured. A CT scan was done and it showed extradural and subdural hemorrhages along with a left occipital fracture and hemorrhagic contusions with perilesional edema. She was shifted to the Neuro ICU and was kept there for observation and treatment. She was referred to the physiotherapist on the third day of admission.

In adolescents and adults, TBI is one of two subsets of acquired brain injury; the other subset is non-traumatic brain injury, which does not involve external mechanical force, such as stroke or infection. TBI is divided into closed and penetrating head injury. A closed—nonpenetrating or blunt—injury occurs when the brain is not exposed. A penetrating, or open, head injury occurs when an object pierces the skull and breaches the dura mater, the outermost membrane surrounding the brain.

Ischemia (restriction of blood supply to tissues) and edema (excessive fluid in the tissues of the body) may trigger secondary mechanisms of injury as well as hypoxia (deficiency of oxygen supply to the tissues of the body) and hypertension.

Brain injuries are classified into mild (concussive), moderate, and severe TBI. The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) grades an individual’s level of consciousness on a scale of 3–15 based on verbal, motor, and eye-opening to stimuli. In general, a TBI with a GCS of 13 or above is mild (80%), 9–12 is moderate (10%), and < 8 is severe (10%, but 25% – 33% mortality). Loss of consciousness (LOC: mild < 30”, moderate 30” – 24 hrs, severe > 24 hrs) and posttraumatic amnesia (PTA: mild < 1 day, moderate 1-7 days, severe > 7 days) are also factored in.

There are two types of amnesia: Retrograde amnesia (loss of memories before the injury) and anterograde amnesia (creating new memories after the injury).

Blast injuries—neurotrauma—can cause traumatic brain injury as well as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Types of TBI

Subdural hematoma: Collection of blood between the dura mater and the pia-arachnoid mater

Intracerebral hematomas

Basilar skull fracture: Leakage of CSF from nose or ear; blood behind the tympanic membrane or external ear

Concussion: Transient mental status alteration (LOC or loss of memory)

Contusions: Bruises of the brain

Diffuse axonal injury (DAI): Shearing of axonal fibers

Subarachnoid hemorrhage

Treatment

The benefits of blue-light therapy in mild traumatic brain injury did not stop with improved sleep. Executive function also improved and there was increased volume of the posterior thalamus, greater thalamocortical functional connectivity, and increased axonal integrity of these pathways. The findings offer insight into the contributions that the circadian and sleep systems play in brain repair.

Concussions

The widespread assumption that youth football players (9-14 years-of-age but make up the largest group of football players in the country) are more vulnerable to concussion and other head injuries than their older, bigger counterparts turns out to be true.In younger players, the fatty myelin sheaths that help protect brain cells haven’t fully developed. They also tend to have larger heads relative to their bodies than adult players do and with less neck musculature to help absorb the force of an impact.

7. Speech and language disorders including, specific language impairments (SLI), developmental phonological disorder (DPD), and stuttering.

Specific Language Impairment (SLI)

About 5% of apparently healthy children have specific language impairment

More than 10 genetic loci have been identified and all of these loci are linked to other neurodevelopmental disorders: Biological markers or “endophenotypes.”

An autosomal dominant transmission of oral motor and speech dyspraxia was identified in a 3-generation British family. Affected family members also have oral-motor dyspraxia, low nonverbal IQ, and nonverbal learning disorders.

CNTNAP2 gene variants are associated with specific language impairment and the FOX2P protein down-regulates (i.e., reduces or suppresses) the expression of this gene.

CNTNAP2 variants may represent susceptibility factors for language-related deficits in both specific language impairment and autism. Different components of autistic-spectrum disorders (e.g., communication deficits, impaired social interaction, rigid or repetitive behaviors) may be under different genetic influences.

Of course, the frontal cortex is involved in language and the basal ganglia in apraxia.

The FOX2P-CNTNAP2 pathway provides a link between clinically distinct syndromes involving disrupted language.

Language impairments that persist to school age are likely to be associated with enduring academic and psychiatric problems.

Mutations (point) and chromosomal abnormalities that affect FOX2P are associated with difficulties in the learning and production of sequences of oral movements which impair speech (developmental verbal apraxia) including expressive and receptive language and production and comprehension of grammar. FOX2P disruptions are rare, however.

The CNTNAP2 gene may be disrupted in Tourette’s syndrome and may cause a severe recessive disorder involving cortical dysplasia (abnormal enlargement of tissue) and focal epilepsy, and it is associated with language regression and autistic characteristics.

Specific language impairment often occurs without difficulties in speech articulation.

Assessment

CELF-R scale (Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals-R).

Children’s Test of Nonword Repetition – this measure is thought to provide an index of phonological short-term memory, which has been proposed as the core deficit in specific language impairment.

Development phonological disorders result in failure to use developmentally expected speech sounds that are appropriate for a child’s or adolescent’s age and dialect such that the resulting speech difficulties interfere with academic or occupational achievement and social communication.

In speaking there is a transformation of a mental representation of an intention into a sequence of rapid, coordinated movements of muscles in the trunk, neck, and upper airway to generate the sounds of language.

Failure to use developmentally expected speech sounds that are appropriate for the child’s age and dialect result in speech difficulties that interfere with academic or occupational achievement and social communication.

Stuttering

There are three major theories of stuttering that emphasize its biological roots and relevant psychological factors: Neurogenic, developmental, and psychogenic stuttering.

The basis of the neurogenic theory of stuttering is that the problem originates in the inability of the basal ganglia to generate neural feedback for appropriate timing of the next segment in the speech stream.

If this problem arises in early childhood it is called developmental stuttering with mean age of onset around 2.5 to 3 years. If psychological factors are significantly involved, such as social anxiety or depression, dysfluent speech may be affected for the worse.

The basal ganglia, in the subcortex, just below the cerebral cortex or “thinking” part of the brain, is interconnected with the cortex as well as the amygdala, brainstem, and thalamus. These collective circuits are known as “basal ganglia-thalamocortical loops” with direct links to “limbic” structures, such as the amygdala. The latter is central to the expression of emotions of fear and anxiety and plays a prominent role in social anxiety and depression. Indeed, negative emotions can exacerbate stuttering in the presence of others suggesting a psychogenic cause of stuttering.

But, there is also involvement of the neurotransmitter, dopamine, in the etiology of stuttering. Dopamine projections from the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) in the midbrain (the forward most portion of the brainstem) project to the striatum of the basal ganglia. When the levels of dopamine in the striatum decrease, there is a lowering or cessation of stuttering, whereas when levels of dopamine increase there is an augmentation of stuttering as well as associated motor and behavioral impulses. This is one reason stuttering might be thought of as a “tic” disorder akin to obsessive-compulsive disorders such as Gilles de Tourette Syndrome.

There are other possibilities for the biological origins of stuttering. One such aspect is dystonic activity in the facial musculature. That is, opponent muscle groups at odds with each other produce involuntary motor activity resulting in dysfluent speech. But stuttering could arise from a disorder in the sensorimotor area of the cortex that controls a region in the throat known as the oropharynx that controls the motor articulatory apparatus used in speaking.

While the mean age of onset of developmental stuttering is in the range of 2.5 to 3 years, it is typically more prominent in boys (2:1; male:female ratio). The recovery rate is in the range of 60-70% within two years after the onset of stuttering but, what is most surprising, is that these early stutterers often demonstrate advanced development of language abilities.

What Might be Some Ways to Relieve Stuttering?

(1) Haloperidol (“Haldol”), a dopamine antagonist, attenuates motor activation and may reduce stuttering.

(2) Speaking at the pace of a metronome (known as the “rhythm effect”) can reduce stuttering by compensating for inappropriate timing cues originating in the basal ganglia.

(3) Reading in unison with others (“chorus speech”) as well as singing can also relieve stuttering, because music provides a separate mechanism for generating internal timing cues when there is aberrant output from the basal ganglia most likely by way of the premotor cortex.

(4) There is also some evidence that modified auditory feedback can improve dysfluent speech in those that stutter.

8. Neurotoxicants that cause various disorders including fetal alcohol spectrum and conduct disorders, methylmercury poisoning, and exposure to organophosphate pesticides, lead, arsenic, toluene, polybrominated diphenyl ethers, phthalates, and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs).

Children and adolescents from 8-15 years of age with higher urinary levels of organophosphate metabolites were more likely to meet the diagnostic criteria for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Why is ADHD associated with organophosphates? Organophosphates inhibit the action of acetylcholinesterase and disruption of cholinergic signaling is one mechanism proposed for ADHD.

9. Genetic disorders such as Fragile-X syndrome, Down syndrome, Williams syndrome, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), schizophrenia-related disorders, and hypogonadotropic hypogonadal syndromes.

Neurodevelopmental disorders are the quantitative extreme of a continuum of normal variation; 50% begin by age 14.

Genetic Disorders Arising Early in Life

Fragile-X syndrome -> Xq27.3 (Band 7.3 in Region 2 on q (long) arm of chromosome X) -> expanded triplet repeat

Rett syndrome -> Xq28

Neurofibromatosis Type 1 -> dominant allele

Down syndrome -> Trisomy 21

Klinefelter syndrome -> XXY (males)

Turner syndrome -> X0 (females)

Triple X syndrome -> XXX (females)

Williams syndrome -> 7q11.2 (males)

Pradi-Willi syndrome -> 15q11 (males)

Angelman syndrome -> 15q11 (females)

ADHD -> DrD4-7r repeat allele

ASD -> 7q31—q33 and 11p12—q13 (abnormalities in social relations, communicative deficits, restricted interests)

All structural variations in DNA involve insertions and deletions known as Copy Number Variants.

Genome -> Transcriptome (RNA) -> Proteome (protein) -> Neurome (brain) -> Phenome (mind) -> Behavior

Childhood Fears

“May we not suspect that the fears of children, which are quite independent of experience, are the inherited effects of real dangers during savage time?

Charles Darwin, 1877

Neurodevelopmental disorders are the quantitative extreme of a continuum of normal variation; 50% begin by age 14.

Down Syndrome

- Hypotonia

- Exhibit distal to proximal activation of muscles (rather than proximal to distal)

- Difficulty in timing the onset and offset of muscular forces

- Interhemispheric transfer degraded because of commissural anomalies

Williams Syndrome

- Deletion of a region on chromosome 7q11.2 containing LIM kinase 1 gene that codes for elastin (highly elastic tissue present in connective tissue allowing tissues in the body to resume their shape after stretching or contracting).

- Poor visuospatial cognition

- Strong social intelligence

A hypothesis about hypersociality in canines. A team of researchers identified genes in dogs that in humans are associated with Williams-Beuren syndrome (or “Williams Syndrome”; there is deletion of 27 genes on chromosome 7 that causes this disorder in humans), a rare genetic disorder. One of the many symptoms of the syndrome is indiscriminate friendliness. They concluded that the genes associated with Williams-Beuren syndrome in humans underlie the friendliness of dogs compared to wolves.

Physical Activity and Mental Health

A very recent study found that total physical activity dropped between ages 12 and 16 years of age, mostly because of decreases in light activity (active movement) and increases in sedentary behavior. Activity levels when kids were younger were linked to their mental health later on; the depression scores at 18 were lower for every additional 60 minutes per day of light activity at 12, 14 and 16 years of age, and higher for every additional sedentary hour.

Peers and Understanding Others

As children mature into adolescence their brains undergo development that makes their reward system particularly responsive to peer influence and especially accommodating to various kinds of social situations. Adolescents, navigating this new social world, are very curious about other people’s behavior and values and are easily influenced by these new ways of being and interacting in the world. And this curiosity partakes of both non-risky and risky behaviors like smoking, sex, driving a car, and other adolescent interests.

A sense of wanting to be included or being excluded by other adolescents can also have an outsize influence on these behaviors. Other factors can include families, friends, schools, neighborhoods, and communities.

But peer influence can help adolescents thrive if they get more involved with their communities or learn how to cooperate or be empathetic with others.

Romantic Relationships and Sexuality

Although romance and dating are relatively common in adolescents, they are not universal. Of adolescents, 13 to 17 years of age, about a third have had a romantic relationship including a more casual or a more serious relationship.

Indeed, a recent survey found that 14% of adolescents are currently in a relationship that they consider to be serious with a boyfriend, girlfriend, or significant other. 5% of adolescents are in a current romantic relationship but do not consider it to be serious and 16% of adolescents are not currently dating but have had some sort of romantic relationship in the past.

On the other hand, about 64% of adolescents indicate that they have never been in a romantic relationship. Of the remaining adolescents (35%), they report having had a romantic partner or have dated in the past. Nonetheless, most adolescents are not sexually active or have never had sex, about 66%. Only about 30% have had some type of sexual activity.

Age is the primary demographic dividing line when it comes to dating and romance. Teens ages 15 to 17 are around twice as likely as those ages 13 to 14 to have ever had some type of romantic relationship experience (44% vs. 20%). These older teens also are significantly more likely to say they are currently in an active relationship, serious or otherwise (18% vs. 6% of younger teens).

Older teens also are more likely to be sexually active, as 36% of 15- to 17-year-olds with romantic relationship experience have had sex, compared with 12% of 13- to 14-year-olds with relationship experience.

Besides age, there are relatively few demographic differences when it comes to teens’ experiences with dating and romantic relationships. Boys and girls, and those with different racial, ethnic and economic backgrounds are equally likely to have been in such relationships.

Identity and Self-Esteem

The development of the self-concept in adolescence is an ongoing achievement. Indeed, the ability to think in possibilities and reason abstractly furthers this sense of themselves. However, the adolescent’s understanding of the self is often contradictory. They may feel withdrawn at certain times but at other times are outgoing, or feel intelligent one moment but unintelligent in another. Research has demonstrated that these contradictions begin to become an overarching concern as they begin to recognize that their personality and behavior morph depending on where they are or who they are interacting with. Nonetheless, given adolescents’ increasing concern about how they appear to others, they are more likely to emphasize traits such as considerateness or friendliness.

As self-concept differentiates, however, so too does self-esteem. This self-esteem emanates from their increasing understanding of their academic, social, physical, and athletic accomplishments in the light of others as well as their increasing competency in handling interpersonal (friends) and romantic relationships, and employment situations. But self-esteem may temporarily drop when making school transitions or moving to another city along with additional stressors such as family disruptions and parental conflict. Self-esteem rises again in late adolescence with increasing competence in adolescent peer relations, appearance, and athletic prowess.

Behavioral Health

- Globally, one in seven 10- to 19-year-olds experiences a mental disorder of one kind or another accounting for about 13% of the global burden of disease in this age group.

- Depression, anxiety, and behavioral disorders are among the leading causes of illness and disability among adolescents.

- Suicide is the fourth leading cause of death among 15-29 year-olds.

- Moreover, the consequences of failing to address adolescent mental health conditions extend into adulthood, impairing both physical and mental health and limiting opportunities to lead fulfilling lives as adults.

Anxiety disorders such as panic or excessive worry are the most prevalent in this age group and are more common among older than younger adolescents. Indeed, 3.6% of 10-14 year-olds and 4.6% of 15-19 year-olds experience an anxiety disorder. On the other hand, depression is estimated to occur among 1.1% of adolescents aged 10-14 years, and 2.8% of 15-19-year-olds. Depression and anxiety share some of the same symptoms, including rapid and unexpected changes in mood. Moreover, anxiety and depressive disorders can profoundly affect school attendance and academic work. And social withdrawal can exacerbate isolation and loneliness whereas depression can lead to suicide.

Many risk-taking behaviors, such as substance use or risky sex start during adolescence. Risk-taking behaviors can be a dangerous strategy to cope with emotional difficulties and can severely impact an adolescent’s mental and physical well-being.

- Worldwide, the prevalence of heavy binge drinking among adolescents aged 15-19 years was 13.6% in 2016, with males most at risk.

- The use of tobacco and cannabis is also a concern. Many adult smokers have their first cigarette prior to the age of 18 years and get addicted to tobacco in less than 72 hours. Cannabis is the most widely used drug among young people with about 4.7% of 15-16 years-olds using it at least once in 2018.

- Interpersonal violence is a risk-taking behavior that can increase the likelihood of low educational attainment, injury, as well as involvement in a crime. Interpersonal violence was ranked among the leading causes of death of older adolescent males in 2019.