Have you ever wondered if home schooling affects a person’s later success in college or how many people wait until they are in their forties to get married? Do you wonder if texting is changing teenagers’ abilities to spell correctly or to communicate clearly? How do social movements like Black Lives Matter develop? How about the development of social phenomena like the massive public followings for Supreme more recently and Harry Potter during many of your childhood’s? The goal of research is to answer questions. Sociological research attempts to answer a vast variety of questions, such as these and more, about our social world.

We often have opinions about social situations, but these may be biased by our expectations or based on limited data. Instead, scientific research is based on empirical evidence, which is evidence that comes from direct experience or scientifically gathered data.

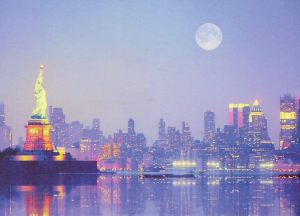

Many people believe, for example, that crime rates go up when there’s a full moon, but research doesn’t support this opinion. Researchers Rotton and Kelly (1985) conducted a meta-analysis of research on the full moon’s effects on behavior. Meta-analysis is a technique in which the results of virtually all previous studies on a specific subject are evaluated together. Rotton and Kelly’s meta-analysis included thirty-seven prior studies on the effects of the full moon on crime rates, and the overall findings were that full moons are entirely unrelated to crime, suicide, psychiatric problems, and crisis center calls (cited in Arkowitz and Lilienfeld 2009). We may each know of an instance in which a crime happened during a full moon, but it was likely just a coincidence.

People commonly try to understand the happenings in their world by finding or creating an explanation for an occurrence. Social scientists may develop a hypothesis for the same reason. A hypothesis is a testable educated guess about predicted outcomes between two or more variables; it’s a possible explanation for specific happenings in the social world and allows for testing to determine whether the explanation holds true in many instances, as well as among various groups or in different places.

Sociologists use empirical data and the scientific method, or an interpretative framework, to increase understanding of societies and social interactions, but research begins with the search for an answer to a question.

References

Arkowitz, Hal, and Scott O. Lilienfeld. 2009. “Lunacy and the Full Moon: Does a full moon really trigger strange behavior?” Scientific American. Retrieved December 30, 2014 (http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/lunacy-and-the-full-moon/).

Rotton, James, and Ivan W. Kelly. 1985. “Much Ado about the Full Moon: A Meta-analysis of Lunar-Lunacy Research.” Psychological Bulletin 97 (no. 2): 286–306.

GLOSSARY

- empirical evidence

- evidence that comes from direct experience, scientifically gathered data, or experimentation

- meta-analysis

- a technique in which the results of virtually all previous studies on a specific subject are evaluated together