“If you control Eskom, you control the South African economy.” — Dr W. de Beer, ex-COO of EDI Holdings (Interview, 23 November 2016)

From its outset, the development of South Africa’s Electricity Supply Industry (ESI) has embodied several striking and somewhat unique features, not least of which is that the discovery of the country’s mineral wealth – diamonds in Kimberley (1860s) and gold on the Witwatersrand (1880s) – roughly coincided with great advancements in electrical-generation technology. This suddenly made electrification both financially and technically viable, and Kimberley switched on its electric street lights in 1882, becoming the first town to do so in Africa and the Southern Hemisphere, and the first in South Africa to have a Municipal Electricity Undertaking[1] (MEU). Another fascinating feature is the ESI’s inordinately rapid development, which took place largely because the vast quantities of power needed by mining quickly attracted power companies and international investors. The predominance of the mining industry meant that supply of electricity to city and town residents, which was more complicated and financially less lucrative, was left to municipalities. Thus, from inception, the ESI developed in two separate streams, creating unique dynamics that still impact the country today.

In immediately recognising that the country’s mineral resources were a “wasting asset” that would inevitably be depleted, the new government, following the formation of the Union of South Africa in 1910, moved quickly to develop and implement an industrialisation strategy. It aimed to modernise based on three pillars. The first was its mineral wealth. The second was cheap labour. It saw the African black population as an inexhaustible and cheap source of labour and set about to deepen racial segregation. The final pillar was the extension of the mining industry’s ultimate requirement: universal, cheap and reliable power. Here, government’s priority was to consolidate and take control of the private-sector utilities supplying industry and the mines. It ultimately achieved this through the creation of the Electricity Supply Commission (Escom) in 1923. Similar control of the municipal ESI,[2] an important but certainly secondary priority, was eventually attained in the 1960s. Until then, however, municipal ESI was kept in check by ring-fencing MEUs’ operations to their area of jurisdiction and imposing limits on how much electricity they could supply to individual users.

As decades passed and apartheid inevitably became untenable, with internal and international pressure mounting, the government became increasingly isolationist and focused on self-sufficiency. Energy was key, and Escom, as sole ESI giant, was allowed significant leeway if it supplied the power the country needed. For example, “innovative” funding practices unlikely to meet the most basic financial accounting guidelines were tolerated, as they eliminated the need for government to provide funding. Inevitably, this went too far, and by the early 1980s, large tariff increases (to fund Escom’s construction programme) had the public and much of industry baying for action. This was containable, but Escom erred by provoking the ire of the authoritarian and reformist state president, P.W. Botha, who immediately reined it in.

Forced to modernise and subscribe to credible financial practices from 1987 onwards, Eskom, by which it was known from then on, emerged an unlikely hero before and after the first democratic elections in 1994. It made noteworthy contributions to providing electricity to the previously unserved, or very under-served, black areas.[3] It was once again enjoying a prolonged golden era, which lasted until the 2005 blackouts, when the lights went off and the Western Cape was plunged into darkness. But this was only a teaser of what was to come, albeit that national government and Eskom moved quickly to assure that the problem would be contained and that there was no crisis (Le Roux, 2006).

Such hopes quickly faded when the entire electricity system came close to collapsing, necessitating national rolling blackouts in late 2007 and early 2008. This had massive repercussions on citizens’ daily lives and the economy, while it also raised serious concerns about the country’s ability to host the FIFA World Cup in 2010.

In 2020, more than a decade after the near collapse, there appears to be no end in sight. The nation still lives under the constant threat of blackouts, despite numerous but ineffective measures taken by government to address the supply shortage. One such measure was building the Medupi and Kusile coal-fired power stations, which were to add a combined 9.6 gigawatts (GW) of capacity. Begun in 2005, construction was bedevilled by huge cost overruns and corruption. The projects are now years behind schedule, with the stations’ few currently operational units breaking down on a regular basis. Another measure that ultimately failed was the initially successful Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement Programme (REIPPPP) that gained international recognition for how well it was managed,[4] but which was abruptly halted by government in 2015, primarily due to Eskom’s refusal to enter into power-purchase agreements while ironically itself being unable to meet demand.

Corruption, patronage and loss of skills at Eskom have put its continued existence at risk (Jaglin & Dubresson, 2016), and as of 2020, it was technically bankrupt. Finally, and of most relevance to this book, a crucial stumbling block remains national government’s unwillingness to allow municipalities to generate electricity without ministerial approval. This was a right that MEUs enjoyed from the turn of the 20th century until the late 1960s, when it was taken away by government at Eskom’s request – with the matter now before the Cape and Gauteng High Courts. As compelling as this narrative is, however, I contest that it is far more complex, especially given South Africa’s institutionalised racism until 1994 and the results thereof. And it is here that we turn to local government as a vital component of the tale.

Internationally, strong local government[5] is viewed as desirable. It is at the forefront of service delivery. In theory, it is also more readily held accountable on issues that directly impact residents – something that is much harder to do if services are administered by the centre, where national interests take priority. Residents are also more likely to trust closer local government than “distant” national government (Siddle, 2011, p.3). And while local government was neglected and subordinate to provincial and national government under apartheid, it was given the same standing as these spheres of government under the 1996 Constitution. Equal does not necessarily mean independent, though, without the requisite financial means. And therein lies the rub.

Central authorities such as national government are loath to share their tax-raising instruments with other tiers of government. This happens for several legitimate reasons, such as:

- To avoid over-taxation;

- To avoid tax exporting (which happens when one jurisdiction or authority imposes taxes on the residents of another);

- To ensure the efficiency of centralised tax collection;

- To avoid taxpayers believing they are being double taxed; and

- To ensure focus on broader objectives, such as income redistribution or macroeconomic stability. (Bird, 2001; Bird, 2011; Slack, 2009; Martinez-Vazquez, 2015; Bahl & Linn, 1992)

Therefore, it was decided and constitutionalised that while municipalities could fund their activities by using the surpluses from the provision of services such as electricity, water and garbage removal, they could not levy taxes that would compete with those of national government. This meant that property tax was the main, and in many instances the only, true tax revenue source for local government. Given the politically charged and weak economic conditions and the imperative of independent and democratic local government at the time, this solution may have been the most appropriate. But was a different model ever an option?

The municipal ESI has a longer history than Escom/Eskom. The Association of Municipal Electrical Engineers (now the Association of Municipal Electricity Undertakings [AMEU]) was formed in 1915 when 22 engineers from 17 municipal towns got together to promote and explore common interests such as technology, national standards, tariffs and distribution systems. Over time, as cities grew, so did the demand for electricity, and the MEUs became utility companies, generating and transmitting electricity within their supply area. Overall, MEUs were known for their competence, and operated profitable businesses, whose income potential municipal finance departments were quick to recognise and exploit. These departments moved to increase tariffs on electricity.

But was this a good idea? The undertakings didn’t believe so, arguing that inflating tariffs to avoid increasing property taxes was effectively levying a tax on electricity. This may be counter-productive, they argued, because consumers could respond by reducing consumption or switching to other fuels. Ultimately, the debate between councillors, who supported the relief of rates from electricity surpluses, and the MEUs, who did not, raged for over 15 years, while the practice continued and gained momentum, making its reversal more and more difficult. In the end, political expediency won the day, and the practice became established and accepted by the early 1940s.

Over the next two decades, MEUs went from strength to strength. Indeed, during the 1940s and 1950s, when Escom was still establishing itself and struggling to meet the ever-increasing demands from mining and related energy-intensive sectors, it entered into long-term supply agreements with Johannesburg Electricity Undertaking (JEU) and did not object to JEU’s applications to construct new electricity-generation plants. Escom then reversed its decision in the mid-1960s when its build programme had stabilised and a national grid was within grasp. Now it convinced government to disallow municipalities from generating electricity, but it didn’t object to MEUs’ existing right to distribute electricity. MEUs were now forced to squeeze as much life as they could from their existing power stations and concentrate on their distribution grids, while entering into supply contracts with the only supplier, Escom. This made Escom a price-maker, and there was little room for negotiation. And with national government putting all its energy into defending and maintaining apartheid, little attention, and even less funding, was given to municipalities, who were expected to be self-funding. The surpluses from user charges to fund municipal operations now became indispensable.

The onset of democracy brought a new set of issues for municipalities. They now had to service black townships, which had largely been ignored by the white local authorities, but which were newly integrated into their jurisdictional areas. Eskom, under its “Electricity for All” programme, which started in the late 1980s, had taken the lead in this regard. It rapidly overshadowed the apartheid government’s efforts to provide services to black areas, which were funded by the Regional Services Council (RSC) levy that was collected in white areas.[6]

The rapid integration of previously under-served areas into municipalities thus put MEUs under immense pressure to respond and keep up. At the same time, they were facing serious structural, technical and financial challenges. On the technical side, they had to absorb new supply areas with different existing equipment and infrastructure. On the financial side, funds that were previously allocated to capital projects were frozen or arbitrarily withdrawn for non-electrical projects. More than ever, protecting and maintaining user fees remained a municipal priority.

The hypothesis of this book is that the provision of basic services for the majority of South Africans who were side-lined under apartheid fell at the feet of local government. This was mandated by the constitutional, regulatory and policy framework after the 1994 democratic elections. The aim was to bring government closer to the people by adopting the principles of decentralised government, which in turn would strengthen democracy.

The right of municipalities to fund their activities from surpluses generated from the provision of services, and primarily from electricity distribution, was enshrined in the Constitution. But while this provided a reliable revenue source, it entrenched an unsustainable business model for MEUs. More importantly, however, it resulted in much deeper implications for the national ESI and is one of the contributing factors pushing the national ESI to breaking point. Here, national government soon recognised the consequences of this decision, and from 2000 onwards, attempted to reform the sector under the decade-long Regional Electricity Distributors (REDs) initiative. However, it was ultimately forced to abandon REDs, leaving the electricity-distribution model that has been in place since electricity was first supplied by municipalities largely unchanged.

More than anything, national government’s failed reform efforts, which did not lack commitment or conviction, point to the complex linkages that exist between:

- Local government and Eskom (its competitor and supplier, in a strained relationship of “co-opetition”), which by extension includes national government as Eskom’s only shareholder; and

- Eskom, government (national and local) and MEUs (in a conflict traceable to the start of the 20th century, with local government as the “political master” of MEUs).

Indeed, the vested interests, which developed over many decades and are now firmly entrenched, point to the need for a much deeper understanding of the situation, if effective and lasting reform is to be accepted by all affected stakeholders. Ultimately, failure to address the status quo is likely to:

- Further hamper local government in achieving its service-delivery mandate;

- Have significant negative financial and operational impacts on the national utility;

- Be a drag on the national and municipal economy; and

- Compromise and frustrate related national policies, such as those on climate change and energy-efficiency targets.

In order to make sense of the complex nature of such a milieu, I use both a conceptual and a theoretical framework.

I use the conceptual framework to disentangle the triangular dynamics between national government, Eskom, and local government. This underpins the research. Through it, I introduce key concepts that help us better understand local government functions and funding, the inherent power dynamics between players, and the competing interests involved. Here, the analysis considers the international context in order to provide a frame of reference and ensure that any distortions of key concepts applied to the local context are not overlooked. Most importantly, such a common point of reference allows discussions in later chapters to flow from a shared conceptual point of departure. We begin with the connection between politics and administration, followed by discussions on notions of centralised and decentralised government; both of which feed into the analysis of municipal funding models that follows (Chapter 3).

For the theoretical framework, I have chosen new institutionalism, which is an approach that explores how the structure of institutions and their rules or norms constrain or enable the choices and actions of individuals who belong to them. This is an appropriate framework because South Africa’s ESI (generation, transmission and distribution) has almost exclusively been built, owned and operated by the state since its genesis at the turn of the 20th century.

On this basis, we view the two primary protagonists, Eskom and MEUs, as political constructs, with new institutionalism accordingly allowing us to triangulate economics, institutions and politics. March and Olsen (1989 & 1995) characterise an institution as: “a relatively enduring collection of rules and organized practices, embedded in structures of meaning and resources that are largely invariant in the face of turnover of individuals and relatively resilient to the idiosyncratic preferences and expectations of individuals and changing external circumstances”.

If institutions are set up to create certainty, reduce transaction costs and improve operational efficiency and/or co-operation for the primary purpose of achieving outcomes valued by society (North, 1990, pp.3–9), then we can classify our protagonists as such. Certainly, as this book will show, these institutions played, and continue to play, a key role in the determination of social and political outcomes (Hall & Taylor, 1996, p.936).

A key objective of new institutionalist analysis is to understand and explain why actors choose to define their interest in a particular way and not in equally plausible alternative ways (Immergut, 1998, p.7). However, new institutionalism also tries to avoid unfeasible assumptions that require too much of political actors in terms of normative commitments (obligations), cognitive abilities and limitations of decision-makers (bounded rationality), and social control (capability) (March & Olsen, 1995, p.16). It factors in that actors are prone to making mistakes. It also offers three primary potential approaches or perspectives:

- Sociological – anchored around sociology, organisational theory, anthropology and cultural studies;

- Rational choice – rooted in economics and organisational theory; and

- Historical – the chosen approach for this book, and which is based on the assumption that institutional rules, constraints, and the responses to them over the long term, guide the behaviour of political actors during the policy-making process.

Significantly, because the historical perspective offers a way to understand the intricacies of political and economic decisions over a truly long period of time, and because it shows that historical developments are seldom straightforward or linear, it is suitable for this book.

It also helps us understand the dynamics of the power relations present in existing institutions by means of which certain actors or interests have greater power than others in the creation and future trajectory of new institutions. This then allows us to identify the reasons why a particular direction was pursued over others, while yielding two important outcomes:

- It isolates the motives of the dominant vested interests; and

- Its capacity to access the actual, rather than the perceived or assumed available alternatives discarded at the time, creates a more complete understanding of the issues involved, so facilitating case study counter-factual analysis.

Here the hypothesis recognises that while institutional change has occurred in South Africa over the last 120 years, the core tenets of policies initiated in the early 1900s continue to influence decision-making. The practices of state institutions in which inertia has taken hold are seemingly impervious to change. And historical institutionalism, based on the concept of path dependence – when the outcome of a process depends on its history (previous outcomes) rather than on current conditions – now provides us with a robust framework to explain present-day outcomes. It does so by recognising the starting point and then tracing the sequence and timing of institutional decisions and exogenous events, to identify those that matter and why. As McCarthy (2011, p.4) explains:

For historical institutionalists history really matters, because the present and the future are connected to the past by the continuity of a society’s institutions. At the heart of historical institutionalism is the idea that policy choices made when a policy is being initiated or an institution formed, will have a continuing influence long into the future. Not only that, the path chosen may often be sub-optimal due to compromise and political expediency.

These themes of historical change and path dependency thus need to be interrogated appropriately to gain a better understanding of:

- Why events have unfolded as they have; and

- What the results are of changes to the mandate of MEUs and the municipal funding model in South Africa at identified critical junctures (points of uncertainty in which the decisions that important actors make can influence the selection of one path over other possible ones).

Since the relationships between the three tiers of government are already complex (as will be seen in Chapter 2) and are further complicated by the monopolistic nature of Eskom, while there are also relational, regulatory, and funding policies (Elson, 2008, p.6) to take into account, each dimension needs to be analysed separately and all as a whole.

In delivering such a detailed historical account and institutional analysis of the municipal ESI in South Africa, the research in Chapter 4 provides context by presenting three international case studies. Most notable of these is England, from whom, as the country’s former colonial master, South Africa copied several governance and legislative frameworks, many of which remain in force. The analysis of the evolution of South Africa’s three tiers of government in Chapter 3 and their use to electrify and industrialise the country (Chapters 4 and 5) also illustrates how national government, from the formation of the Union in 1910, pursued, and continues to pursue, two fundamental but diametrically opposing ambitions:

- A financially “self-sufficient” local government, which in reality is over-burdened and has limited scope to collect revenue needed to administer its mandated municipal functions (this revenue comes in the form of property tax and surpluses from services – with the majority by far being raised from electricity sales); and

- A vertically integrated utility with a key role in the economy (Chapter 4).

The inherent contradictions between these ambitions drive an enduring conflict that has reached fever pitch in the last 20 years.

Complicating matters even more is the added paradox of conflicting national objectives. On the one hand, neo-liberal economic policies adopted by government are supportive of cost-reflective tariffs (tariffs based on the true cost of electricity and that are not falsely reduced or inflated) to enhance competitiveness and productivity. Yet, on the other hand, national policy calls for developmental local government, where a significant portion of funding is sourced through cross-subsidisation (which happens when a municipality uses surpluses from providing services to people to fund its activities). Ultimately, this book shows that such contradictions and dichotomies have been, and continue to be, the basis for the discord that exists in the ESI – leading to broader political and economic fallout for the country, and to the death knell of municipal Electricity Distribution Industry (EDI) reform from the late 1990s onwards.

This was demonstrated once again from 2010 on as a new and imminent structural crisis: the so-called death spiral. This threatens the entire ESI, and the EDI specifically, as detailed in the case study in Chapter 5. Yet, the failure of government (national, local, NERSA, and Eskom) to adequately deal with the crisis, and perhaps even its inability to do so due to the lock-in of long-ingrained trajectories, is impacting negatively on developmental local government – particularly service delivery. And if left unresolved, it will undoubtedly result in the same impasse as always (failure to restructure) but with graver and graver economic and political consequences that South Africa as a nation can ill afford.

Having now set the scene, and before we delve into decentralised local government in Chapter 1, it’s important to make a note on the structure of this book. Electrification largely coincides with the discovery of minerals in South Africa. From this period until 1910, however, the analysis limits itself to contextual background. From Union onwards, three time periods have been identified, mostly because particular groups dominated the control of each period:

- From 1910 to 1948, the English-speaking population controlled mines and the economy;

- In 1948, the nationalist, Afrikaner-supported National Party (NP) won the elections, formalised apartheid, and wrested significant control of the economy for Afrikaners; and

- The NP ruled until the first democratic elections in 1994, when the African National Congress (ANC) came into power and the third and final period began.

While the historical analysis is detailed for each of these three periods, it is restricted to 2017 in the case of the final period, since the research was only conducted up until this date. (See the Addendum, which provides a brief update for the period 2017 to April 2021.)

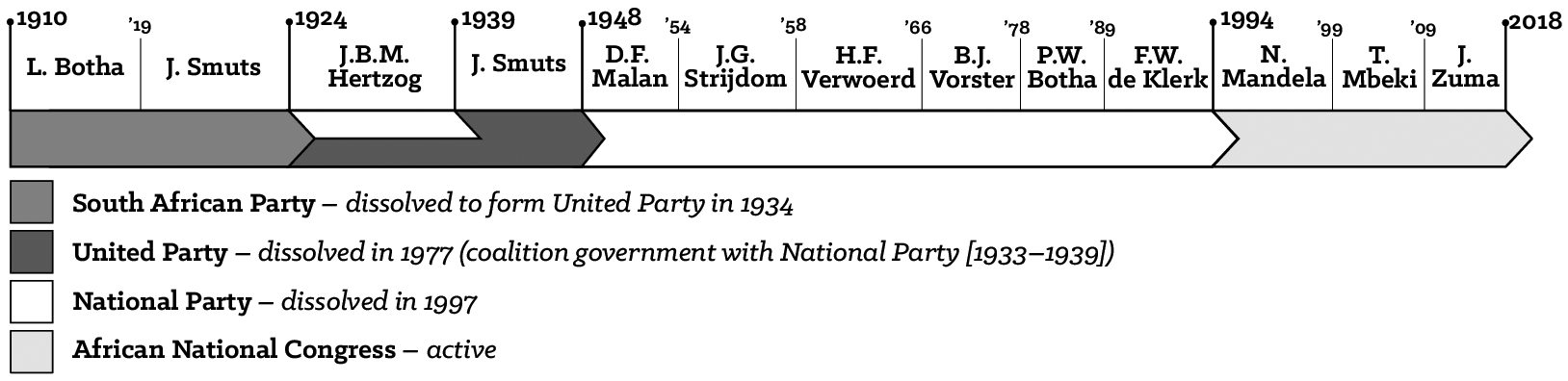

Figure i illustrates how just four political parties, and in reality, three – since the South African Party was dissolved to form the United Party in 1934 – have dominated executive power in South Africa. This is relevant because common sense would dictate that during long periods of uncontested control, the removal of existing policies to introduce new ones would be significantly easier. Indeed, since 1910, in a period of 107 years, South Africa has only had 12 heads of state,[7] implying that on average each one has held their position for 9.5 years.[8] Furthermore, the transition from one period to the next is characterised by a fundamental transfer of power and control from one cultural or race group to another. Under these circumstances, the opportunity for sweeping change to take place is not only probabilistic but expected (whether it materialises or not).

Note

Apartheid legislation segregated people based on racial classifications. The Population Registration Act No. 30 of 1950 divided the population into three main racial groups: Whites, Natives (Blacks), and Coloured people (people of mixed race, as well as people of Indian origin). Race was used for political, social, and economic purposes. These classifications in no way represent the views of the author, and the author does not accept the use of race as a basis for discrimination. These terms are used to reflect written sources, data and also to highlight how race was the basis of all government planning prior to 1994.

- The term “electricity undertaking” was introduced by the Transvaal Power Act No. 15 of 1910, which defined the generation and distribution of electricity in a specific area. In 1956, the Association of Municipal Electricity Undertakings (AMEU) adopted the following definition: “A local authority carrying on an electricity supply undertaking.” “Supply” included generation and distribution. ↵

- This book makes reference to both municipal “ESI” and “EDI” (Electricity Distribution Industry). Until the late-1960s, MEUs generated and distributed electricity within their jurisdiction; hence “ESI”. In 1969, municipalities agreed to relinquish their right to generate electricity in return for exclusive distribution rights; hence “EDI”. The terms are not used interchangeably but refer to the time periods. Where both periods are being addressed, then “municipal ESI” is used. The Electricity Pricing Policy of the South African Electricity Supply Industry, issued by the Department of Minerals and Energy (DME) in 2008, defines EDI as the “distribution industry connected to supply voltage not exceeding 132 kV” and ESI as “generation, transmission and distribution”. ↵

- During apartheid, local government was split according to race. As a result, it was disjointed, and separate infrastructure existed for each race group, with white residential areas well serviced and areas inhabited by all other races having a very low level of service. ↵

- By 2013, after three rounds of bidding, 64 projects valued at US$14 billion to generate 3.9 GW had been selected (Eberhard & Naude, 2017). By 2017, the updated figures were: 112 IPPs, 6 422 MW, and R201.8 billion (DoE, 2017). ↵

- The book refers to both “local government” and “municipalities”. For the purposes of this book, these terms have the same meaning and are used interchangeably to avoid excessive use of the same word. ↵

- The Regional Services Council Act No. 109 of 1985 aimed to achieve economies of scale and increase efficiency by reducing the duplication of services based on race, by providing them on a joint basis. To fund this, the Act called for a levy to be charged by employers on employee wages which had to be paid in their region. ↵

- This excludes President Cyril Ramaphosa, who was elected state president in February 2018. ↵

- Excluding Kgalema Motlanthe, who was caretaker state president for eight months in 2008/9, from the time Thabo Mbeki resigned until national elections were held. ↵