Between 2017, when the research this book is based on was first published, and early 2021, much has changed. Yet, much has also stayed the same. At the time of writing, the lessons of the past have yet to fully inform the strategies of the future, but shifts have occurred and are worth touching on.

National Government

On 13 February 2018, the ANC recalled President Jacob Zuma, despite his protestations and pleas to complete his term. The ANC’s senior leadership could no longer ignore the damage wreaked by the Zuma administration: for the first time since 1994, the party lost the Johannesburg, Tshwane and Nelson Mandela Bay metros in the local elections of 2016; there was flagrant – and now publicly exposed – corruption; high unemployment; and poor service delivery. Seizing the moment, ANC President, Cyril Ramaphosa, replaced Zuma on a ticket to address corruption, and led the party to win the national elections.

Since then, a key aspect of government’s focus on corruption has been the activity of the Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of State Capture, headed by Deputy Chief Justice Raymond Zondo (the Zondo Commission of Inquiry). Ironically, and in retrospect perhaps even comically, it was launched by President Zuma as one of his final acts to “investigate allegations of state capture, corruption, fraud and other allegations in the public sector including organs of state”.[1]

And although the Inquiry is still ongoing in April 2021, the testimonies to date have revealed a level of corruption, incompetence and maladministration that has shocked even battle-weary South Africans already quite used to banal, bizarre and blatantly dishonest behaviours from those in power through the years. Indeed, many see ex-President Zuma’s refusal to now testify at the commission he launched as his final kick in the teeth to the rule of law; Zuma may yet face a gaol term for this. Time will tell if the impasse of his refusal to appear will be addressed through a legal or political solution. For the purposes of this book, however, it is important to note that Eskom is infamously enjoying centre stage at the Inquiry as a crucial exponent of the machinations of state capture and its devastating consequences to the nation.

President Ramaphosa had also pledged to reduce the size and cost of his Cabinet when coming into office, which he duly did, by reconfiguring it from 36 to 28 members and merging seven ministries.[2] Here, of particular relevance to our context, is that the Department of Mineral Resources (DMR) was reunited with the DoE to create the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (DMRE), with Gwede Mantashe, the DMR incumbent, retaining his position at the new ministry. The minister began his political career in the 1980s as branch chairperson for the Matla colliery in the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), rising to become NUM’s secretary general, and moving on to hold the same position for the ANC in the Zuma era. The decision to merge the two ministries and still retain Minister Mantashe is thus inexplicable for two reasons.

Firstly, South Africa’s primary energy future had always been almost exclusively coal-based (except for imported petrol – and even here, just under 30% of supply is local coal-to-gas synthetic fuel). And while in this paradigm it may appear sensible to have the two portfolios in one ministry, South Africa however is a signatory to the Paris Agreement. It recognises that to meet its obligations it must drastically reduce and phase out coal entirely; this naturally creates unhealthy internal conflict within a single ministry.

Secondly, even if one notes that other factors, such as a political compromise to maintain the fragile balance within the National Executive Committee may have informed the president’s decision to merge the two ministries, the selection of a “mining man” as minister to orchestrate and oversee the energy transition appears counterintuitive. It runs the risk of at best delaying such transition (as has already transpired) and at worst derailing it – with dire long-term consequences for the economy, the natural environment and the health of South Africans who reside in coal regions, whose air and water supplies are already besmirched by ongoing coal-mining activity.

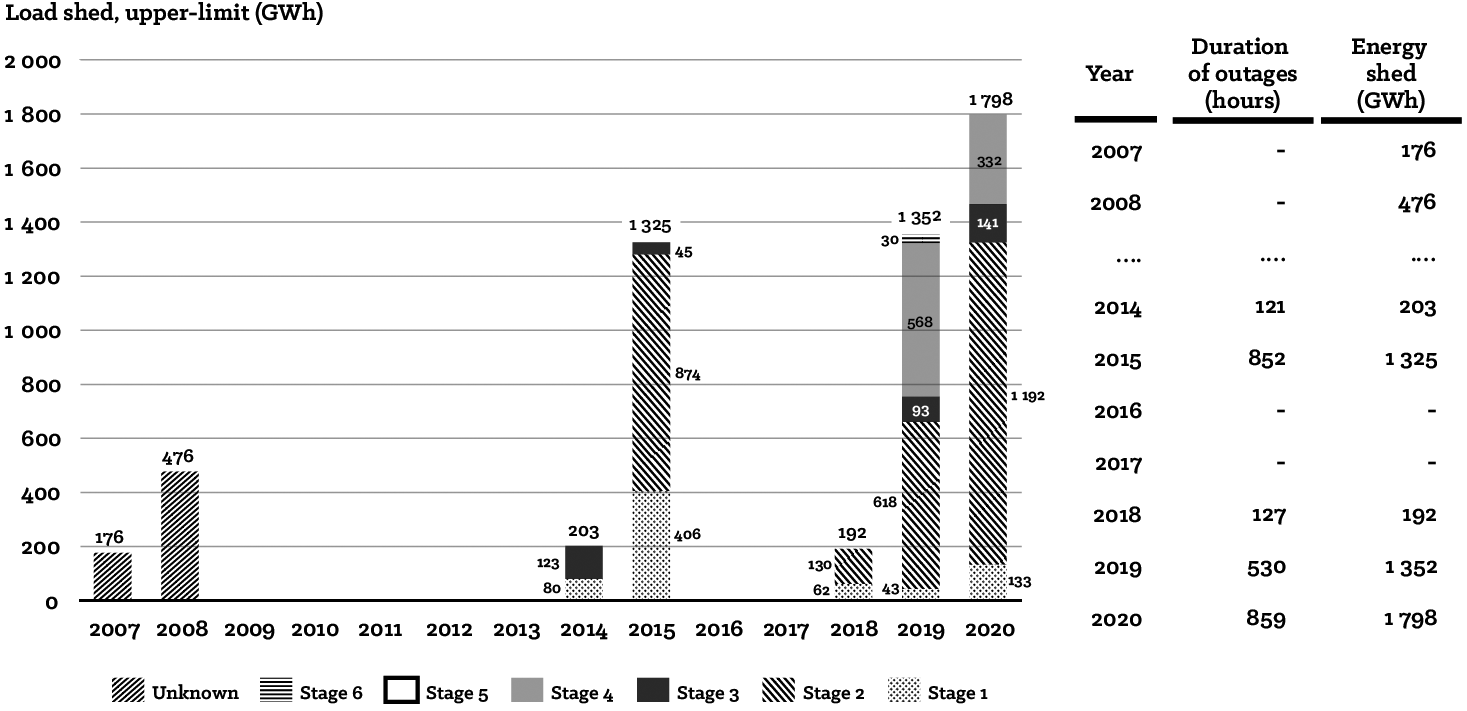

As for the issue of secure energy provision, the reality in early 2021 is that the electricity supply crisis is getting worse, not better. Indeed, the Energy Centre of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) reported that 2019 was the worst year of power outages since 2007. In 2019, blackouts persisted for a total of 1 352 GWh – or 530 hours, as shown in Figure iv. It was also the first time that Stage 6 load-shedding was implemented – a level at which over one-third of Eskom’s total capacity was offline.

Source: CSIR (2021)[3]

ESI Reform

Notwithstanding the grim state of the country’s electricity system, no meaningful reform has been forthcoming from the DMRE; while its procurement of additional electricity from renewables at times almost seems reluctant. How else does one explain that electricity outages started again in 2018, but it was only on 21 February 2020 that the DMRE acted? After two years of inaction, they finally issued two ministerial determinations for new generation capacity. The one was for 2 GW of “emergency power” in a process meant to be fast-tracked; and the other was for ~12 GW from various energy sources. However, the preferred bidders for the supposedly fast-tracked emergency power process were only announced more than 12 months later (in March 2021), with many critics pointing to a skewed request-for-proposal document which favoured liquified gas, resulting in the bulk being allocated by the DMRE minister to Karpowership.[4] A highly controversial decision which may be challenged, further exacerbating electricity supply shortages; while the bidding documents for the second allocation are yet to be released by the IPP office. Recognising that it is not solely the DMRE who oversees the process, the general lack of pace does however raise concerns about government’s level of urgency.

Consequently, private consumers are no longer waiting for government to act, and it is estimated that more than 2 GW of unregistered[5] photovoltaics for own use had been installed nationally by February 2020.[6] This is likely to intensify the income crisis for local government and Eskom, thus hastening the death spiral for both.

Simultaneously, municipalities remain unable to get any of their generation applications approved. A key example is the City of Cape Town. In 2015, the mayor of the city submitted an application for a 300 MW generation licence, but was advised by NERSA that a licence could not be issued without a ministerial determination. This unfortunately also coincided with the final period of the Zuma presidency, during which turmoil reigned and there were frequent ministerial reshuffles. And while the city made numerous attempts to engage with each of the subsequent ministers, it never received a response or an acknowledgement. This inability to enter into any reasonable dialogue triggered inevitable court action, and the matter found its way to the High Court, attracting significant media coverage and interest.

At the time, power outages were a daily occurrence, and President Ramaphosa had taken charge – thus increasing expectations of actions being taken – and things were looking promising when, in his State of the Nation Address on 13 February 2020, the president announced: “We are taking … measures to rapidly and significantly increase generation capacity outside of Eskom … We will also put in place measures to enable municipalities in good financial standing to procure their own power from IPPs.”

On 14 May 2020, the City of Cape Town, NERSA and the DMRE presented their arguments to the High Court judge. On 12 August 2020, the ruling was announced. This favoured the DMRE, on the basis that Section 41(3) of the Constitution states that for intergovernmental disputes, those involved “must make every reasonable effort to settle the dispute by means of mechanisms and procedures provided for that purpose, and must exhaust all other remedies before [approaching] a court to resolve the dispute”.[7]

In October 2020, the DMRE then gazetted amendments[8] to the electricity regulations for new electricity generation capacity – now opening the way for “municipalities in good financial standing to develop their own power generation projects”. The amendments still require ministerial approval, together with other requirements, which include a feasibility study and proof of compliance with, amongst others, existing regulations, the IRP (DMRE national electricity plan) and municipalities’ IDPs. The amendments also impose new and unique obligations, which are additional to what is required under the REIPPPP, thus raising questions about their constitutionality. Moreover, no detail is provided on how the applications will be evaluated in relation to the IRP, how the applicants will be consulted, the maximum timeframe for an application to be processed, or whether any recourse is available for unsuccessful applications. Thus, the amendments are at odds with the policy direction given by the president, and if this is not corrected, it is likely that the matter will find its way back to the courts.

Eskom

Leadership changes were also made at Eskom during this period. Respected CEO, Phakamani Hadebe, left the utility in May 2019 after 12 months at the helm. Largely seen as a victim of circumstance, where the nature of South African politics did not allow him to make the deep changes needed to stabilise the utility, he resigned.[9] André de Ruyter then took the helm in January 2020, and his tenure to date can be characterised as measured, while gradually yielding results. Generation plant managers are now being held accountable for performance (unheard of in the recent past); more than 5 000 employees have been referred for financial irregularities[10] and internal corrupt practices; hundreds of employees have left the utility to avoid internal investigations; and a civil suit for R3.8 billion has been initiated against former employees.[11]

Simultaneously, the utility is in the process of restructuring, or “divisionalisation” in the CEO’s terminology. This will see the vertical separation of its three core businesses, as it is split into distinct units (Generation, Transmission, and Distribution) in line with the president’s directive. This formal separation will facilitate the creation of the establishment of a standalone Independent Transmission Grid System and Market Operator (ITSMO)[12] – a key development, as this will reconfigure the process of buying and selling and most importantly create a new “energy landscape” for municipalities, especially if REDs is back on the agenda. This structural change coincides with the realisation that coal is not the future; there is a set target to decarbonise by 2050. However, major challenges remain – not least of which is the utility’s unsustainable ballooning debt of R464 billion – thus necessitating an unpopular 15% tariff increase that will hasten the death spiral. Indeed, Eskom’s parent ministry announced on 13 February 2019 that the utility was technically bankrupt.[13]

Eskom’s final state is anyone’s guess in 2021, but it appears to have a steady pair of hands at the helm.

Municipalities

As explained in Chapter 5, municipal revenues initially increased when Eskom started raising electricity tariffs, but these then subsequently fell. This has been reconfirmed by recent analysis, as expressed in an article by Dr Neva Makgetla:

As a group, municipal income from electricity after paying Eskom climbed 20% from 2009 to 2015, but then fell 3% through 2019 before crashing 40% in the year to June 2020 as the pandemic hit. In eThekwini from 2010 to 2019 businesses cut their electricity use by 6%.[14]

In another article, Dr Makgetla details the dire economic state of the municipalities not able to pay Eskom for the electricity supplied. It has less to do with their consumers not wanting to pay, and more with users’ inability to pay:

According to Quantec estimates, the economies of the five most indebted cities have shrunk 0.6% over the past five years, while their population has grown 4.5%. In the same period the national economy expanded 4.1%, and SA’s population by 7.7%.[15]

In Johannesburg, CP is in an even more precarious state than it was in, in 2017. Several CEOs have come and gone, and the city’s mayor, Herman Mashaba, resigned on 21 October 2019, ostensibly leaving more problems than he had inherited. His grandstanding on how he would clean up the finances of the city and root out corruption may have amounted to little more than rhetoric – with CP’s finances “in a shambles”,[16] according to the new mayor, Geoff Makhubo. There was only a 90% collection rate in 2019, against a target of 94%, and the problems with the billing system have worsened;[17] there is the added pressure of a R5.6 billion overdraft;[18] and non-technical losses peaked at 35.80% in Quarter 3 of 2020, a significant increase from 2017 (see Table ii). CP’s audited annual financial statement for the year ended 30 June 2020 attributes the declining financial performance to lower gross margin percentage and declining revenue figures largely from non-technical losses (billing errors, illegal connections, and theft).[19]

On a more positive note, CP employed an Eskom veteran, with over 30 years of experience, as its new CEO from 1 April 2021. It is hoped that he is given the time and support needed to restore the utility.

Concluding Comment

The unwelcome return of power outages has once again thrust the spotlight on Eskom. And as has been custom for over a century, municipalities remain the poor cousin, with their plight not getting the required attention. It is difficult to see how long this can be sustained for. A CP spokesperson stated on 19 October 2020 that they are “losing about R2-billion annually, which includes vandalism and infrastructure”,[20] and that shockingly, many of these acts are being committed by former employees. The cow that delivered so much for so long, is now a financial burden on the city, and if this continues, it can only be a matter of time before provincial or national government will be forced to intervene. Of course, a new and growing contributor to revenue loss is reduced consumption due to embedded generation. The death spiral for CP now seems real, and is now recognised by local governance ratings agency Ratings Afrika.[21] The agency’s Municipal Financial Sustainability Index scores (out of 100) (see Table iii) measure six municipal financial components:

- Operating performance;

- Liquidity management;

- Debt governance;

- Budget practices;

- Affordability; and

- Infrastructure development.

Source: Ratings Afrika

It need not be that dire though, and one hopes the national government will recognise the urgency of the situation and introduce the necessary reforms.

Ultimately, the dysfunctional duet between Eskom and municipalities that has often been driven by limited national government action, must now be resolved. And it is complicated further by Eskom’s abovementioned divisionalisation reform and the proliferation of poorly controlled own-use generation, which undermines the current municipal funding model.

- See https://dpe.gov.za/in-the-judicial-commission-of-inquiry-into-allegations-of-state-capture-corruption-and-fraud-in-the-public-sector-including-organs-of-state/ (accessed 26 April 2021). ↵

- See https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2019-05-29-ramaphosa-cuts-cabinet-from-36-to-28-ministers-half-of-whom-are-women/ (accessed 26 April 2021). ↵

- See https://researchspace.csir.co.za/dspace/handle/10204/11865 (accessed 27 April 2021). ↵

- Powerships are barge- or ship-mounted floating power plants. Karpowership Powerships are all-in-cost, fast-track solutions that can operate on heavy fuel oil and natural gas. ↵

- On 10 December 2017, the minister of energy amended the Electricity Regulation Act of 2006 so that all generation systems installed solely for own use are exempted from needing a licence, but it is a requirement (punishable by a fine) that they are registered with NERSA. ↵

- This was revealed at an electricity workshop held on 10 February 2020 in a discussion between Eskom and the South African Photovoltaic Industry Association. ↵

- See http://www.energy.gov.za/files/media/pr/2020/MediaStatement-DMRE-welcomes-High-Court-Order-12082020.pdf (accessed 26 April 2021). Also see https://www.polity.org.za/article/electricity-regulations-amended-to-allow-municipalities-to-develop-or-buy-power-2020-10-16 (accessed 1 June 2021). ↵

- See Government Notice No. 1093 http://www.energy.gov.za/files/media/pr/2020/DMRE-publishes-Amendments-to-Electricity-Regulations-on-New-Generation-Capacity-16102020.pdf and https://www.engineeringnews.co.za/article/electricity-regulations-amended-to-allow-municipalities-to-develop-or-buy-power-2020-10-16 (accessed 26 April 2021). ↵

- See https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2019-05-30-why-eskom-ceo-phakamani-hadebe-resigned/ (accessed 26 April 2021). ↵

- See https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/31197/ (accessed 26 April 2021). ↵

- See https://www.news24.com/fin24/economy/eskom/weve-said-goodbye-to-hundreds-eskoms-de-ruyter-on-corruption-clean-up-20201204 (accessed 26 April 2021). ↵

- See https://www.biznews.com/entrepreneur/2020/10/21/eskom-unbundling (accessed 26 April 2021). ↵

- See https://www.sabcnews.com/sabcnews/eskom-is-technically-insolvent/ (accessed 26 April 2021). ↵

- See https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/opinion/columnists/2021-02-22-neva-makgetla-its-easy-to-blame-eskom-but-what-about-local-government/ (accessed 26 April 2021). ↵

- See https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/opinion/columnists/2020-11-09-neva-makgetla-eskom-punishes-without-understanding-why-municipalities-cant-pay/ (accessed 26 April 2021). ↵

- See https://www.power987.co.za/news/city-of-joburgs-finances-are-in-shambles-geoff-makhubo/ (accessed 26 April 2021). ↵

- See https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/national/2021-04-19-joburgs-beleaguered-billing-system-still-in-disarray-r70m-later/ (accessed 26 April 2021). ↵

- City Power Quarterly Report 2021, https://www.citypower.co.za/city-power/Annual Reports/2020_2021_Q1_Report.pdf (accessed 26 April 2021). ↵

- City Power 2019/2020 Integrated Annual Report, see https://www.citypower.co.za/city-power/Pages/Annual-Reports.aspx (accessed 26 April 2021). ↵

- See https://www.enca.com/news/city-power-losing-billions-due-theft-vandalism (accessed 26 April 2021). ↵

- See https://bit.ly/3dTg2cm (accessed 26 April 2021). ↵