The previous chapters have sought to illustrate the policy dimension of national government’s ongoing, over-a-century-long pursuit of two fundamental, but diametrically opposed objectives, whose inherent contradictions have driven an enduring conflict since the formation of the Union in 1910 that has reached fever pitch in the last two decades:

- An over-burdened, financially “self-sufficient” local government with limited scope to collect revenue to fund its mandated municipal functions (having only property tax and surpluses from services as sources of revenue – with the majority of income raised from electricity sales); and

- A vertically integrated national utility, Eskom.

Complicating matters even further are conflicting national objectives. On the one hand, neo-liberal economic policies adopted by government support cost-reflective tariffs to enhance competitiveness and productivity. Yet on the other hand, national policy calls for developmental local government, with a significant portion of funding sourced through cross-subsidisation.

The research presented in this book has thus shown that these dichotomies have been, and continue to be, the basis for the discord that exists in the ESI and which leads to broader political and economic fallout for the country, and to the demise of municipal EDI reform from the late 1990s. This was once again demonstrated from 2010, as a new and imminent structural crisis, the so-called death spiral, threatens the entire ESI, and the EDI in particular. Certainly, the failure and perhaps even inability of national and local government, and of public entities such as NERSA and Eskom, to adequately deal with the crisis due to lock-in, is impacting negatively on developmental local government, and specifically on service delivery. If this is left unresolved, it will undoubtedly result in the same impasse (failure to restructure) – with even graver economic and political consequences.

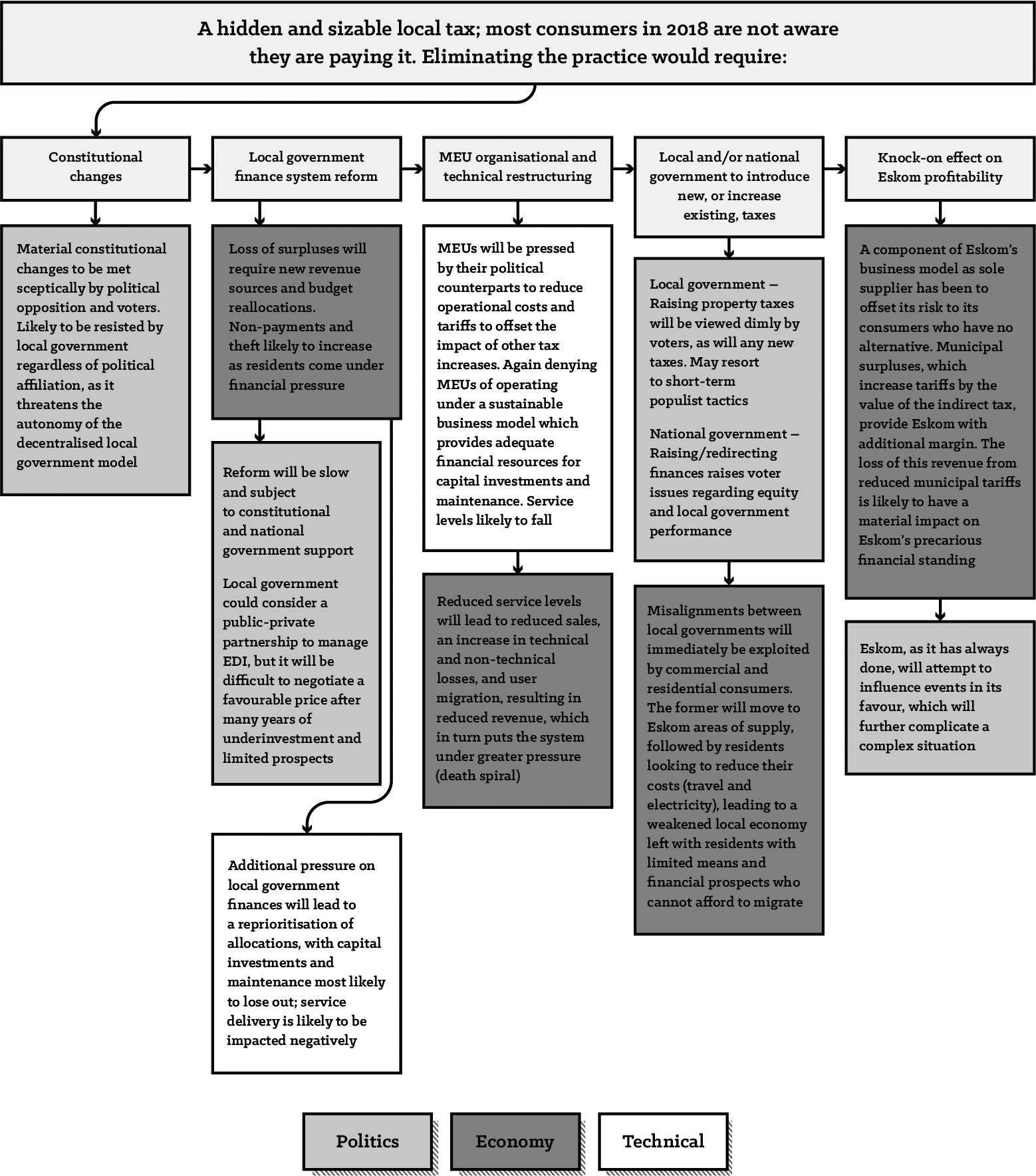

Ultimately, this book has interrogated the complexities created by using surpluses from electricity sales to cross-subsidise municipal functions, which conflicts with national priorities; while the historical analysis I have undertaken has shown that this practice is not new. It developed over a prolonged period to satisfy other, but ultimately competing and counter-productive, objectives of national government, and the linkages it created have by now strengthened to such an extent that disentangling them is no longer straightforward. Indeed, the effects of such an unravelling would not only be universal, but likely extreme, as shown in Figure ii.

In retracing the history of all actors within this context, we have seen the complex relationship between the national economy, the three tiers of government, and the ESI – where each actor is represented by different institutions with diverse mandates and interests – resulting in the inevitable situation of contradictory/conflicting policy positions and competing objectives. Such a situation may not immediately qualify as being either overly unique or material, as many other functions or services offered by government and its agencies require compromise. But how it unfolds may matter; and for the EDI it does. As this book has shown, here, the current institutional arrangements regarding municipal EDI are reaching breaking point, with dire social and economic consequences for all; in a situation not receiving the attention it deserves, as it is overshadowed by events engulfing Eskom. However, connection points between these two crises exist. Both shield operational inefficiencies, as well as consumer resistance, manifested at one end by reduced consumption and electricity theft, and at the other through defection (fuel switching and embedded generation) and improved energy efficiency. Ultimately, national outages caused by mismanagement (coal-supply contracts), plant shutdowns (maintenance), delays in commissioning new plants (mismanagement), financial distress (corruption, staff strikes and pay demands), will attract public attention over localised municipal outages varying from one MEU to the next; but both have equally ominous consequences.

This all then makes it necessary to determine the extent to which circumstances matter and to examine how events evolved. Here, two options exist:

- A narrow analysis can be conducted, as was done for the implementation of REDs, which focused on national government priorities. This is not to imply that the approach was rushed or not taken seriously; the EDI reform process lasted for about 12 years and cost billions of rand. However, the research has pointed out how important factors were sidestepped, underestimated or flat out ignored – issues which were material sticking points for local government and MEUs. This includes, for example, the contradiction and perceived unfairness of the Constitution allocating municipal distribution to local government, but MEUs being required to cede the “golden share” to national government under the proposed REDs model; or

- A detailed and accurately sequenced historical account of events can be made, providing a complete understanding of institutional and policy development. Such understanding is more likely to provide the basis upon which appropriate decisions can be taken.

To date, the former, more expedient approach, has led to little reform, and if anything, has put the system under greater strain. Thus, to contribute towards a resolution, this book presents a detailed and holistic analysis, which not only introduces new insights, but also explains the rationale behind the “stickiness” of existing path dependency. In this, a further distinction also needs to be made between grasping historical events that resulted in the present-day dynamics of the current crisis, versus attempting to take corrective action. For the former, a historical analysis is appropriate, whereas for the latter, a historical understanding is required.

Within the context of developing historical understanding, and with so many of the findings in this research pointing to the currently entrenched system’s resilience and ability to endure, an important question is: Are the odds then not heavily stacked in favour of continued path dependence? I believe, possibly not. Table i on pages 193–196 illustrates how the relief of rates (cross-subsidisation) has progressively evolved into a cumulative crisis since it was first flagged. In the table, concerns raised by the AMEU at the 1936 conference (and one subsequent factor identified in the research) are listed in the first column. The status of each is then rated at three key points in time: the two identified critical junctures and the present day (2017). Research findings then justify the allocated rating where necessary – with the three rankings, or metrics, applied being “Limited”, “Moderate”, and “Critical”. Here, the objective is not to provide a financial quantification of the impact of cross-subsidisation on the economy; nor does this analysis mean to imply that electricity tariffs are higher solely, or even largely, as a result of cross-subsidisation. Electricity tariff increases have, specifically from 1969, almost exclusively been the sole preserve of Eskom; and indeed, a 2015 comparative analysis found municipal tariffs in several categories to be cheaper than Eskom’s (Yelland, 2015).

The table’s objectives are thus twofold. The research has demonstrated how the relief of rates was inherited from the British system and retained even when Britain, along with New Zealand and New York City, amongst others, discarded (indeed outlawed) the practice in the 1930s. Locally, at this time however, with Escom’s sole focus on servicing the mining industry, the practice was serving local government funding requirements well, becoming ever more entrenched as residential demand grew. These increasing returns naturally led to stickiness despite credible economic theory to the contrary, which remains the case in 2017. Thus, the first objective is to ascertain how the context has changed. In other words: Why do concerns identified in the mid-1930s only appear to be threatening the entire system some 80 years later? Is it that it was a necessary requirement for all of them to manifest? Here, it then also becomes particularly significant to rate the indicators at other historical points to understand the variations in the ranking results. Thus, when one examines the table, the complete dominance of the “Critical” ranking in 2017, suggests a tipping point, where a new critical juncture that opens the door to change, may be imminent – not as an exogenous shock, but rather as a culmination of events of an ongoing process. The second objective is thus to cast light on the potential of such a juncture occurring, which if handled correctly, will allow for meaningful and long-overdue reform to occur. Here, this suggests that the probability of change may significantly advance within the next five years – not by design – but through the combination of:

- Deterioration in municipal finance – caused by a combination of corruption, incompetence, a weak economy, and cross-subsidisation reaching its economic limits; and

- Revolts related to service delivery and infrastructure, which may force change through protest action by lower-income consumers and reduced consumption by MEUs’ core profitable consumers, who through technological advances (Arthur, 1989) now have viable and cost-effective alternatives.

| Concern with relief of rates | 1936 | 1970 | 1996/98 | 2017 |

| Inflated tariffs raise the likelihood of loss of revenue through reduced sales/fuel switching | Limited – ESI in growth phase. Supply shortages as national grid and large Escom plants still under construction | Limited – South Africa’s economically most-prosperous decade | Moderate – excess supply leads to tariff decreases (real terms); still unaffordable for many | Critical – 300%-plus increase in tariffs from 2008 to 2013 |

| Research findings | ||||

| Theory warns that business and residents evade, or relocate to municipalities with lower costs. The research found JEU higher electricity costs contributed (not primarily but not insignificantly) to the early 1990s migration to Sandton, and from 2000 to high non-technical losses | ||||

| Concern with relief of rates | 1936 | 1970 | 1996/98 | 2017 |

| High tariffs ignore the needs of poor and large households (regressive tax)[1] | Moderate – “poor-white” problem | Limited | Critical – addressed through national policy | Critical – relief provided through Free Basic Electricity (FBE), but insufficient in a context of high unemployment, inequality and low economic growth (see Chapter 2: 2.6.5 on page 51) |

| Research findings | ||||

| The research has found that nationally, and specifically in Johannesburg (as per the case study), the high levels of non-payment are a combination of an inability to pay, and protest at the inadequate service-delivery levels | ||||

| Concern with relief of rates | 1936 | 1970 | 1996/98 | 2017 |

| Compromises prudent accounting practices (depreciation, redemption), leading to deterioration of system as surpluses are prioritised for relief of rates | Limited – infrastructure relatively new. AMEU concerned about the future | Moderate – networks and generation plants ageing. Increased demands on local government | Critical – service delivery to previously unserved BLAs funded largely through cross-subsidisation | Critical – same as 1996/98 |

| Research findings | ||||

| Table 5.6 (on page 175 in Chapter 5) demonstrates the extent to which CP’s performance is deficient in meeting the NERSA performance guidelines | ||||

| Concern with relief of rates | 1936 | 1970 | 1996/98 | 2017 |

| Transfer of surpluses leads to little or no reserves, requiring MEUs to take loans to finance new equipment and operations, adding interest costs and necessitating more tariff increases | Moderate – as per AMEU minutes | Moderate – no evidence found to suggest otherwise. Municipal tariffs were increased in line with Eskom | Critical – case-by-case basis. Johannesburg, on the verge of bankruptcy, diverted all surplus revenue to the municipal cause | Critical – MEU under-investing by as much as R2.5 billion per annum |

| Research findings | ||||

| Although financial statements were not scrutinised to determine if this was indeed the case, the research did confirm that large surpluses are being transferred to subsidise other municipal functions at the expense of capital investment | ||||

| Concern with relief of rates | 1936 | 1970 | 1996/98 | 2017 |

| Electricity provision must be efficient (cost-reflective rates and without subsidy) to stimulate the economy | Moderate – tariffs 14.5% higher to fund relief of rates | Moderate | Critical – new users are low users, with most unable to afford costs | Critical – high tariffs have led to theft and delinquent accounts |

| Research findings | ||||

| The relief of rates has aided the false economy under which Eskom operates (expanded upon in the closing paragraphs below) | ||||

| Concern with relief of rates | 1936 | 1970 | 1996/98 | 2017 |

| Doubtful practice – surpluses vary annually; an over-reliance may lead to funding problems if sales/surpluses decrease | Moderate – WLAs in growth phase | Moderate – WLAs about to enter into economic decline phase | Moderate – Eskom over-supply keeps system in balance, but warning signs present | Critical – High tariffs and losses have led to large surplus reductions |

| Research findings | ||||

| The research has confirmed that this has materialised since around 2010. Raised individually by municipalities and through SALGA, gaining in momentum – primary topic at CIGFARO 2017 conference | ||||

| Concern with relief of rates | 1936 | 1970 | 1996/98 | 2017 |

| Technological advances may lead to consumers switching to other energy sources, especially if tariffs are too high | Limited – new electrical equipment and alternatives limited | Limited – new electrical equipment and alternatives limited | Limited – electrification and reduced electricity tariffs fuelled demand | Critical – high tariffs, technological alternatives and climate change now driving demand down |

| Research findings | ||||

| Concerns with regards to the death spiral are not limited to Eskom. Conversely, consumers who cannot afford the tariffs are reverting to unsafe energy forms or theft, undermining the national electrification project | ||||

| Concern with relief of rates | 1936 | 1970 | 1996/98 | 2017 |

| Some municipal functions are unprofitable by their nature; thus cross-subsidisation is necessary – swings and roundabouts | Critical – thus proposal to place a cap on transfers and levy a direct tax | Critical – made worse by loss of generation rights, placing greater pressure on municipal finances | Critical – address apartheid inequities, but do so in a transparent manner viz direct tax | Critical – increase national contribution and/or introduce new municipal revenue sources |

| Research findings | ||||

| The central theme of this research, with findings that support it, is that local government has been allocated insufficient and inappropriate (cross-subsidisation) own-revenue sources to fund developmental government, undermining the legitimacy of government | ||||

| Concern with relief of rates (post-1936) | 1936 | 1970 | 1996/98 | 2017 |

| Corruption and/or reduced competency of local government, leading to budget shortfalls | No evidence found to suggest that this existed | Moderate – no evidence of widespread corruption. Purging of municipal staff to make way for Afrikaans speakers had affected service, leading to calls for a commission of inquiry into municipal incompetence |

Critical – employment equity at government level leads to loss of experienced staff who were often replaced by inexperienced political appointees. Corruption on the rise since early 1990s | Critical – as per auditor-general and NT findings, manifested by correlation between technical failure and alignment with political factions |

| Research findings | ||||

| As per 2017 comment | ||||

Eskom Epilogue

While musing on the findings in this book and the implications thereof for local government, its MEUs and its finances, however, it is worth taking some time to reflect on the elephant in the room: Eskom.

Before doing so, it would be unfair and unkind to overlook the efforts and achievements of the countless dedicated employees who over the past 95 years committed themselves to building a world-class utility, which continues to power the economy and was the fourth-largest in the world at one point.

The utility however has enjoyed a charmed life, which may very well be coming to its teleological end as it faces the same “death spiral” challenges that all large utilities around the world are grappling with. Eskom’s situation though, is perhaps more extreme. Here, the majority of the country’s minerals, the “wasting asset”, have been extracted – ore yields are declining, mining depths increasing, and amidst a prolonged cycle of depressed commodity prices, many mines are closing or contracting, with the US$ price of gold, for example, decreasing by 10% for the period 2012 to 2017. It would be alarmist and overstating matters to believe that mining activity is nearing the end of the road. It is not, but it has declined, and this can be seen by the electricity demand, with volumes in 2017/18 at the same level as those in 2007.

Of greater concern however (and here take your pick between actual outcome or DoE margin of error), “For the financial year ending March 2018, the actual total electricity consumed is about 30% less than what was projected in the Integrated Resource Plan of 2010”[2] (Radebe, 2018). Thus, the economy has started to transition to a significantly less energy-intensive service one, which profoundly changes the Eskom modus operandi and necessitates realism and an ability to adapt its business model to ensure its survival. Indeed, Jaglin and Dubresson (2016) predict its demise within a five-year period – at the very least in its current structure.

On reflecting somewhat deeper into what is present-day Eskom, the author can’t help but conclude that the special place that it has held in government’s decision-making, both pre- and post-1994, created a false economy for it, which has finally caught up with the utility. Several instances of this, drawn from previous chapters, are detailed to illustrate the point.

Firstly, the Johannesburg case study has shown that JEU was a well-operated utility, which was a net seller of electricity to Escom in the 1950s. This provided the municipality with an additional source of revenue, which it used to reduce the impact that cross-subsidisation placed on its tariffs. In the 1960s, when Escom’s new plants had been commissioned and its purchases from the JEU started to decline, the JEU responded by keeping its generation costs below Escom’s, and when they were higher, it took supply from the national utility to ensure that its tariffs were competitive and its surpluses maximised. Although not ideal from Escom’s perspective, it was sheltered from the full effect of competitive forces by the Power Act of 1910, which disallowed MEUs from selling to large users and outside their area of jurisdiction, with the result that the JEU was not able to maximise returns on cost advantages. The only outlet for any generation surpluses was Escom, who paid a lower tariff than what large users would; and only if it needed supply. If this was not enough: Escom conspired and succeeded in ending municipal generation in 1969, in flagrant disregard of the provisions of the Power Act. Incensed, the JEU took the matter to the highest court to challenge the Provincial Administrator’s refusal to approve the application, but political pressure from senior levels in national government (as it was widely expected that the court would rule in the JEU’s favour) saw them withdraw the case just days prior to the court hearing.

Secondly, both Escom and Eskom enjoyed privileges that other state-owned enterprises did not. This manifested in different forms. With regards to funding, anything was possible – from the conventional (local and international loans, pre- and post-1994), to the creative (the Capital Development Fund in the early 1970s), to the blunt (large tariff increases at short notice to fund shortfalls and inefficiencies – again pre- and post-1994 – and most recently with the new build programme of Medupi and Kusile). Turning to demand projections, which underpinned Eskom’s new build programme; these were overly optimistic in the 1960s and 1970s and more recently from 2005, while in both instances the basis of the projections was questionable and actual demand failed to match the forecast, thus resulting in large long-term surpluses and debt.

Then there is Eskom’s ability to change national government’s stance to its benefit, but almost always to the detriment of the national economy. Here, we can consider its influence on the Borckenhagen Inquiry, or its stacking of the newly formed NER in the mid-1990s with Eskom retirees (led by its former CEO), or its ability to convince the DoE to get the ISMO “off the DoE’s table”, to name but a few. These examples suggest that the short periods during which South Africa has had amongst the cheapest electricity tariffs in the world, have come at a larger cost over the long term, particularly when operational inefficiencies take hold. These necessitate bailouts in the form of government guarantees or loans and/or steep and rapid tariff increases to consumers big and small; with an unacceptably negative impact on the indigent.

How this will conclude is unclear, as Eskom, during its 95-year history, has demonstrated an uncanny ability to survive. Indeed, correct action commenced from late 2018, with the appointment of a credible CEO (Phakamani Hadebe) and a new chairman of the board (Jabu Mabuza), and the replacement of Minister Lynne Brown (with Pravin Gordhan) leading to an (ongoing) clean out of tainted management. Whether or not the new team can restore governance, confidence and morale and chart a new strategy to overcome key challenges, remains to be seen. Under the circumstances, Jaglin and Dubresson’s prediction seems not only reasonable but likely.

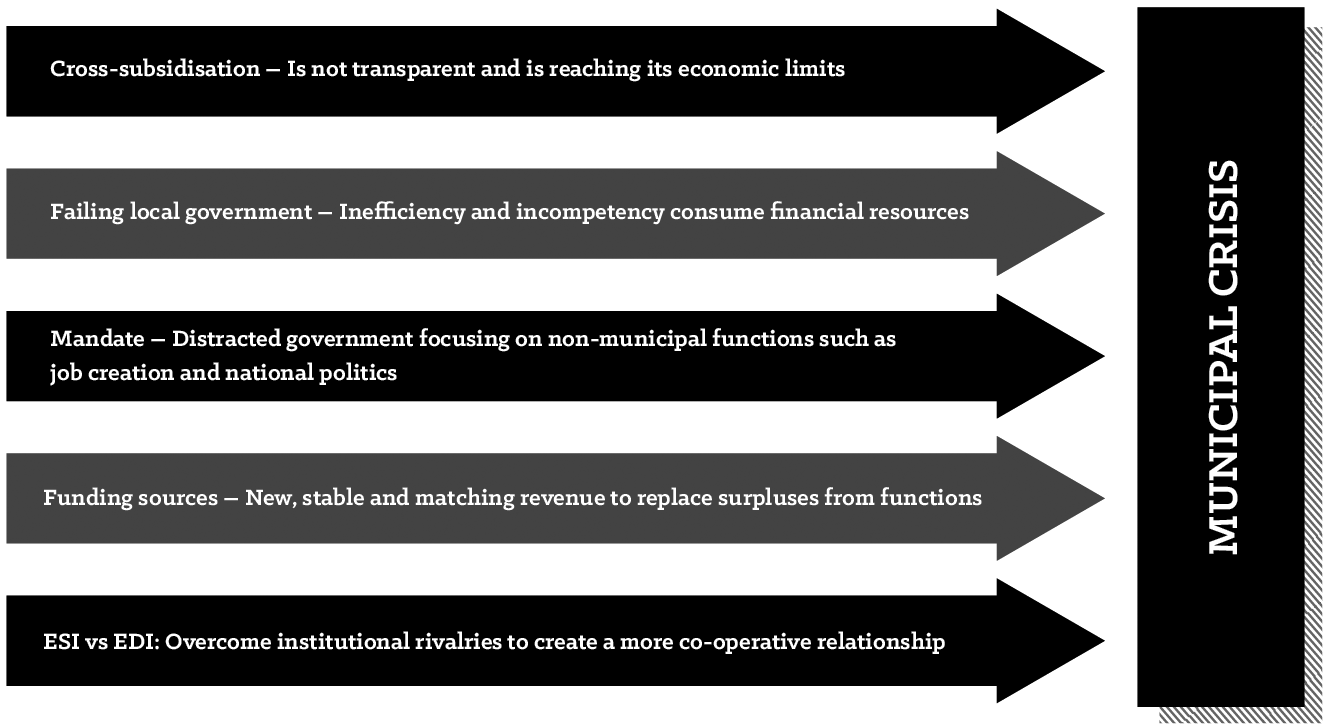

In closing, it should be noted that municipal EDI is one of many issues affecting local government, as observed by several academics and most notably Siddle (2011), Stanton (2009) and Thornhill[3] (2016). Indeed, successful or more sustainable EDI reform will by no means resolve the state of crisis of local government. And while NT may very well argue, with some truth, that local government is sufficiently funded, issues of performance (incompetence and financial mismanagement) are where the bulk of the challenges lie. Figure iii lists several matters plaguing local government, and once again stresses that these are unlikely to be resolved in isolation or without full understanding of their root causes.

Ultimately, the incalculable scope of challenges facing local government, as well as electricity supply and distribution, need not be seen as well-nigh insurmountable. It is thus the hope of this book that by unearthing forgotten but relevant information and using a recognised theoretical framework, the author has provided credible reasons for the strong linkages that exist between electricity and politics, and delivered fresh perspectives. These perspectives, the author believes, have the potential to inspire positive new directions, which in some way contribute to eventually breaking the current impasse – ending the repeating cycle electricity provision has found itself locked into for over a century.

- BLAs were excluded under apartheid. Once absorbed in 1994, the real situation is reflected. ↵

- According to the DoE website, “The Integrated Resource Plan in the South African context is not the Energy Plan – it is a National Electricity Plan. It is not a short or medium-term operational plan but a plan that directs the expansion of the electricity supply over the given period. Its purpose is the identification of the requisite investments in the electricity sector that maximize the national interest.” See http://www.energy.gov.za/IRP/overview.html (accessed 25 March 2021). ↵

- Interview with the author, 13 May 2016. ↵