1

“For anyone who might not yet have noticed, political decentralization is in fashion.” — Treisman (2007)

1.1 Introduction

With local government playing such a prominent role in this book’s analysis – and particularly in the triangular dynamics between it, national government and Eskom – this chapter provides a working definition of the concepts and terms applicable. It especially focuses on recurring themes directly impacting on discussions and analyses in some of the chapters that follow. We will unpack the functions of local government, its funding, its relationship with national government, and the inherent power dynamics and competing interests of the different parties involved. We consider both the international and the South African context in order to provide a common point of reference and ensure that we don’t make any distortions when applying our key concepts to South Africa. Firstly, we explore the connection between politics and administration. Secondly, we unpack notions of centralised and decentralised government. Both of these topics feed into the analysis of municipal funding models that follows.

1.2 The Link Between Politics and Public Administration

In “The Study of Administration”, Wilson (1887) argues that administrators are autonomous from politicians and can apply the principles of resource optimisation in the execution of their duties. They are thus able to manage the public sector in an efficient and independent manner. Given that public administration is an extension of the state, however, often with much more than administrative optimisation at play, a more pragmatic approach eventually came to the fore in the 1980s. This held that true independence from politics in public administration is not possible (Svara, 2001, p.180).

Accepting that the primary concern of public administration is to achieve objectives that are predominantly politically determined, and that public administration and politics cannot be separated, the question Tӧtemeyer (1985, p.1) poses is: Does the administrative function complement politics or is it subordinate to it? Tӧtemeyer argues that the answer is to be found in the extent to which democracy prevails in a country, whereby society holds government accountable through electoral democratic processes. This means it is necessary to maximise citizen participation at local government level. Mechanisms must be in place to ensure local governors are held responsible to the governed for their actions (Blair, 2000, p.35).

1.3 Centralised and Decentralised Government

1.3.1 Overview of and Developments During the 20th Century

The definition of democratic local government is universal: An administrative and executive body that is elected by the community it represents to preside over the inhabitants of a specific geographic area. Local governments vary in size and structure and operate under different conditions, depending on a country’s system of government. In theory, local governments strive to meet their inhabitants’ needs for goods and services in a cost-effective manner (Alao et al., 2015, p.61). In fulfilling these functions, and within the overall system, local governments have varying degrees of power to act autonomously, and are authorised to undertake legislative, administrative and semi-judicial functions. Local government has the power to implement policies and programmes, raise revenue, formulate budgets, employ staff and operate going concerns to provide services. But local government is subordinate to central government and is generally the lowest “tier” of government. Central government is the first tier; provincial or regional government is the second tier; and local government is the third tier.

Conceptually, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “New Deal” welfare state, introduced during the Great Depression of the 1930s, shifted power to national government and pioneered centralised government, or what is more commonly known as “big government” (Wallis & Oates, 1998, p.156). Western Europe then adopted a similar model to rebuild its post-World War II (WWII) economies and also as a mechanism to keep tight control in the Cold War era, during which there was the constant threat of war. The Soviet Republics and Eastern Europe adopted an even more centralised model under communism, with a similar situation also existing under dictatorships. There were numerous such dictatorships between 1945 and 1970, after which many began to fall. Simultaneously, Keynesian economics, which justifies government intervention through public policies in the pursuit of full employment and price stability, dominated Western economic theory and policy after WWII.

This all started to change in the 1970s, when many advanced economies suffered stagflation, which combined inflation, slow growth and large public-sector deficits (Jahan et al., 2014, p.53; Sanderson, 2001, p.297). The ability and capacity of “big government” to solve all the problems was reconsidered, and many sought to reduce its size and scope by adopting a more decentralised approach, with power in the USA, for example, shifting back to individual states. This trend grew, and by the late 1980s, governments around the world entered a cycle of decentralising fiscal, political and administrative responsibilities to lower levels of government (Work, 2002; Litvack et al., 1998; Weale, 2006; Hood, 1995; Heller, 2001; Manor, 1999; Treisman, 2007). Explaining this, Litvack et al. (1998, p.1) cite the introduction and strengthening of democracy around the world, and “the plain and simple reality that central governments have often failed to provide effective public services”.

1.3.2 Decentralisation

Decentralisation is not easily implemented, and the achievement of public-sector governance and reform objectives is largely contextual, because application varies (Siddle & Koelble, 2013; UNDP, 1999; Litvack et al., 1998; Treisman, 2007). As Manor (1999, p.10) points out, decentralisation in India is bound to mean something different to decentralisation in Botswana.

A key precondition of decentralisation is central government consciously and willingly transferring power to local government, and the necessity of functional co-existence of the two. In this, the existence of democratically elected local government, held accountable by its constituents, creates legitimacy and autonomy, and implies that authority is distributed horizontally rather than hierarchically (Heymans & Tӧtemeyer, 1988, p.5). Importantly, decentralisation occurs over time, is a process, and is the product of reforms. Moreover, decentralisation is further complicated by there being three different types (Siddle & Koelble, 2013, p.20):

- Administrative: The responsibility to deliver services is transferred from national to sub-national levels, resulting in a deconcentration of power;

- Fiscal: Revenue from central government and the authority to raise revenue from local sources are transferred from national to sub-national levels; and

- Political: Political power and authority is transferred from national to sub-national levels, which involves balancing the exercise of power between various levels of government.

At a practical level, then, decentralisation aims to transfer duties to the lowest level of government capable of executing them (Work, 2002, p.5; UNDP, 1999 quoting Kaul) and can be categorised into three levels:

- Devolution provides the highest level of autonomy, in which local government finds itself outside of direct central government but is still subject to national policies and laws such as the constitution;

- Deconcentration transfers power to an administrative unit of central government; and

- Delegation involves transfer of specific duties under a contractual arrangement.

From the above, it is evident that in the case of deconcentration, local government exists in name only and is devoid of local accountability, as units of central government are not accountable to local citizens (and voters), but to their vertical hierarchy. Which is why it is crucial to separate decentralisation and deconcentration.

1.3.3 Benefits and Shortcomings of Decentralisation

Treisman (2007) sought to determine the effects of decentralisation, but concluded that the net results were inconclusive. The primary reason was that consequences tend to be complex and obscure, as many effects pull in different directions. Table 1.1 now summarises the perceived benefits and shortcomings of decentralisation.

Source: Treisman (2007)

The view of the World Bank is that decentralisation can yield positive results (efficiency and improved public-sector responsiveness) or negative results (threat to economic and financial stability). This is determined inter alia by how it is applied, as well as prevailing local conditions (Litvack et al., 1998, p.107). Ultimately, it is about potential – guaranteeing nothing (USAID, 2000, p.8), which is a disturbing conclusion, given the vital importance attached to the success of decentralisation by the World Bank (Siddle, 2011).

Ultimately, decentralisation has not proved to be the panacea for reforming and transforming local government operations and strengthening democracy. Mixed views are held on its effectiveness, while a growing number of studies show that implementation is difficult and that each experience is unique and likely to yield mixed results (Agrawal & Ribot, 1999; Johnson, 2001; Meenakshisundaram, 1994).

1.4 Overview of Municipal Finance Sources

1.4.1 A View on the Relationship between National and Local Government

A feature of all countries, except for micro-states, is a second tier of government below the centre. South Africa has had three tiers since 1910: national, provincial and local.[1] Lemon (2002, p.18) identifies three reasons why a modern country requires additional tiers:

- Administration: Large, centralised government is bureaucratic and needs a mechanism to administer functions more readily and efficiently at local level;

- Legitimisation: A lower tier of government provides legitimacy by allowing a certain degree of local autonomy; and

- Redirection of blame: Here, Lemon cites Dear (1981), Clark & Dear (1984) and Rakodi (1986, p.437), who astutely note that a benefit of national government reducing its level of control is that, when useful, it can redirect blame for some of its “knotty problems” (Cockburn, 1977), such as service delivery, to subordinate levels of government.

The role of local government in South Africa has thus been crucial, both before and after the first democratic elections in 1994, where:

- Prior to 1994, all municipalities were required to be almost entirely financially self-sufficient (resulting in some autonomy and independence within the context of a highly centralised and autocratic state); and

- After 1994, the Constitution elevated local government to one of three spheres of government. The Constitution mandated local government to anticipate and address local needs through the provision of specified functions, for which it is entitled to collect revenue (in addition to the funding it receives from national government in the form of equitable share and financial transfers).

If local government addresses local needs satisfactorily, this will ensure national government’s legitimacy, and this has been South African local government’s primary focus. This need is especially acute in South Africa, where local government’s ability to deliver basic services to the majority of the population, who received very poor service delivery or were even excluded totally, is directly linked to improving the electorate’s impression of national government’s capacity and capability. This ultimately leads to tension between local and national government. At times, conflict between two levels of government will occur even if both spheres are governed by the same political party, and may even go as far as the lower tiers opposing the state (Lemon, 2002, p.20). And while degrees of autonomy differ amongst countries, local municipalities are not sovereign and would have no existence without national government, so their ability to act independently is inherently limited.

Local government provides many different services to its customers (residents), for which it charges a fee. And its structure, role and mandate allow it to be motivated by servicing needs rather than by accumulating profit. It can also tax its residents for additional revenue (Freire & Stren, 2001, p.171). Levying taxes is of course unpopular with residents, so it is imperative that local government does this in a manner that is deemed equitable and reasonable.

For the purposes of this study, it was found that research into local government structures and financing models from the mid-1980s on was most beneficial. It was from this time onwards that the decades-long global political status quo under the Cold War was challenged and changed in the following ways:

- The communist system in Eastern Europe and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) fell in 1989;

- China relaxed direct political control over its citizenry;

- Keynesian economics gave way to neo-liberal policies; and

- Rapid advances in technology, transport and communications irrevocably transformed business and social practices.

These factors precipitated globalisation, one of whose knock-on effects was the acceleration of urbanisation, which was to place massive and continuous pressure on municipal service delivery.

During this period in South Africa, apartheid’s demise was both certain and imminent; with densely populated, mostly poverty-stricken black townships, which had little to no access to municipal services, having to now be absorbed into local government. This would have massive ramifications on the future structure of local government, and it ultimately influenced the final outcomes and decisions about the roles and responsibilities allocated to local government in the 1996 Constitution, as well as how they would be funded.

In keeping with the period in question, the next section provides a theoretical overview of international municipal funding models developed and encouraged by international development-finance agencies and academics at the time. These sought to assist and influence the new municipal financial frameworks being simultaneously implemented across the world, including in South Africa.

1.4.2 Municipal Funding Models

At its core, local government has four basic sources of funds, with several variants for each source (Table 1.2).

Source: Bahl & Linn (1992)

Mainstream economic thinking under the fiscal decentralisation model supported local government generating as much revenue as possible from its own sources, but complying with two basic principles:

- The service or function provided must be clearly linked to the revenue source; and

- Services should be financed by their beneficiaries.

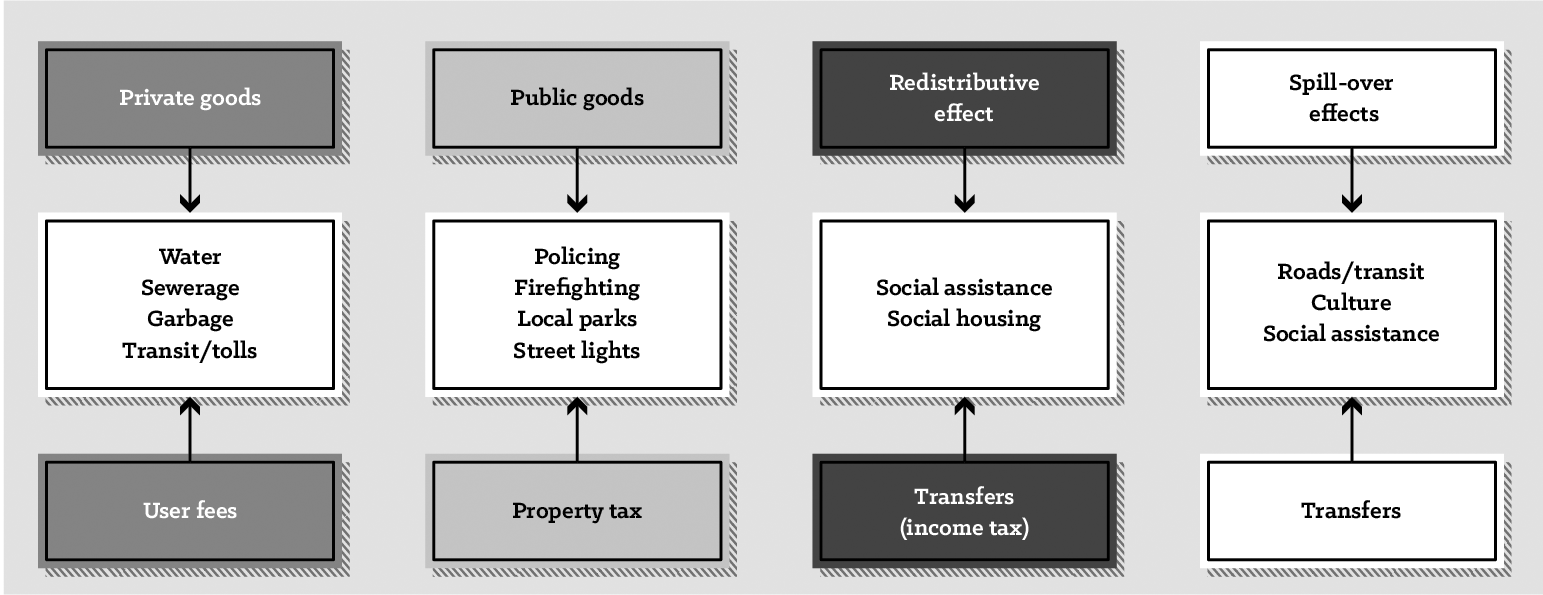

Under these conditions, private services supplied by local authorities are thus excludable. For example, if a consumer does not pay for the service, they can be cut off. Public services, such as street lighting and firefighting, should be financed from local taxes. Redistributive and spill-over effects (such as social assistance and housing) exceed the mandate of local government, but if responsibility for these lies with local government, they must be funded from inter-governmental transfers, and not from user fees or local taxes (Figure 1.1) (Farvacque-Vitkovic & Kopanyi, 2014; Slack, 2009; Bird, 2000, 2001 & 2011; Martinez-Vazquez, 2015; Dewees, 2002; Freire & Stren, 2001; Boyle, 2012; Bahl & Smoke, 2003a).

Source: Slack (2009)

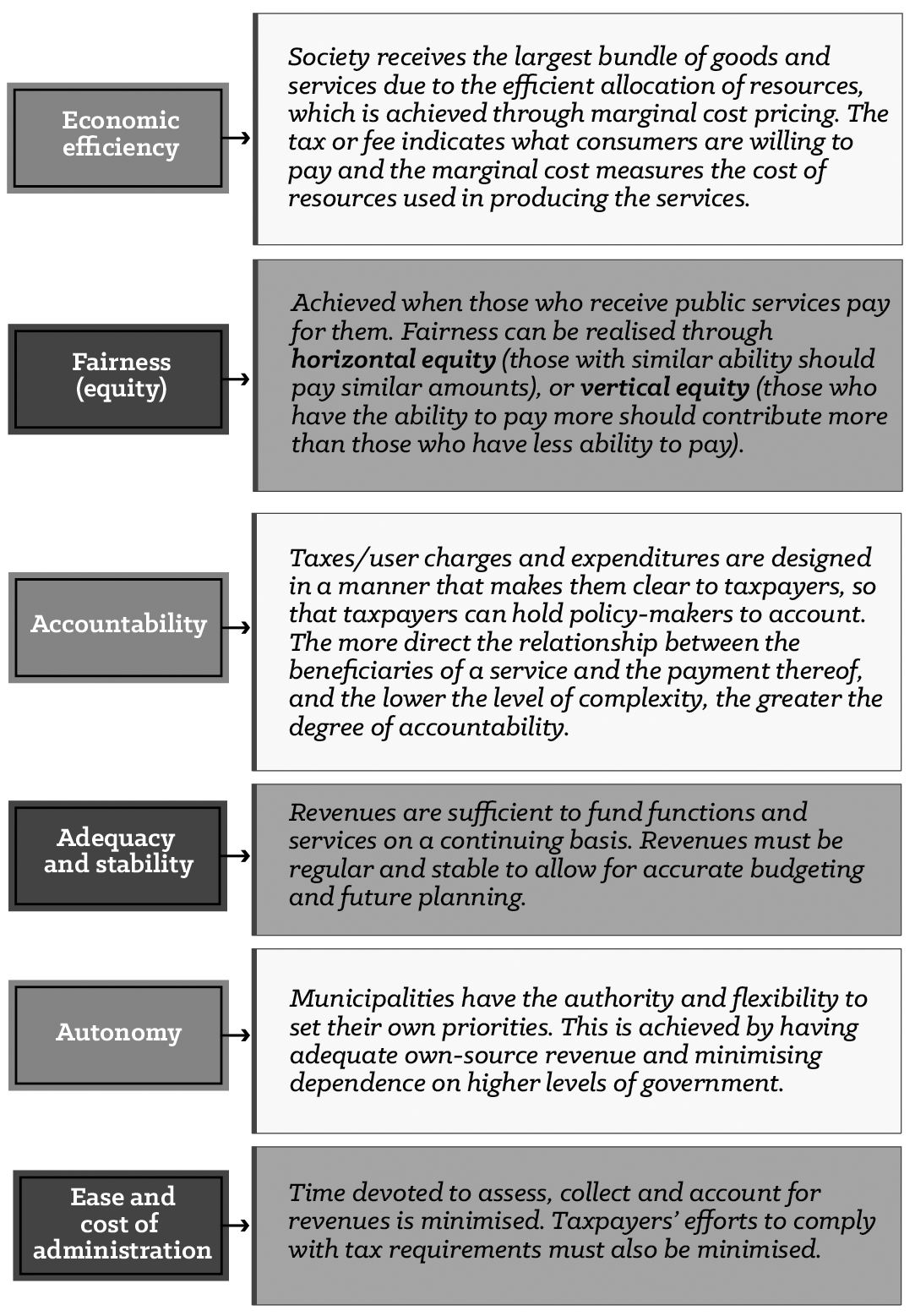

To the greatest extent possible, the financing tools listed in Figure 1.1 should aim to conform to as many of the economic principles listed in Figure 1.2 as possible.

In most cases, the extent to which local government can use funding sources rests with national government. For example, the South African Constitution (1996, Section 228–230) allows provincial government to impose taxes, Value Added Tax (VAT), and general sales tax to fund its activities, but these forms of taxation are specifically excluded for municipalities. Thus, by extension in this context, the lower the level of financial self-sufficiency, the greater the ability of central government to influence how funds are prioritised and allocated. However, urbanisation in developing countries is unlikely to increase municipal revenues by a commensurate amount, because the income elasticity of existing taxes is bound to decrease as unskilled and semi-skilled people migrate to urban areas (Bahl & Linn, 1992).

In truth, fiscal decentralisation policies put forward in the 1980s to improve service delivery and reduce poverty (Slack, 2009, p.14) had two consequences:

- Central and provincial functions were offloaded or downloaded to local government, along with budgetary authority, but almost always without taxation authority, which central government retained; and

- As a result, revenues under local government control rarely matched expenditures (Slack, 2009; Bird, 2001 & 2011).

We now consider each of the revenue sources individually.

Property Taxes

Universally, the most popular municipal tax instrument is property taxation. Depending on how the property tax is applied, it can be regressive or progressive,[2] but only marginally so. Advantageously, property taxes are inexpensive to collect, uniform in their application, and easily understood by residents, as they target landowners who are likely to be more affluent. The tax does have several weaknesses, though:

- The register must be updated regularly, as property prices fluctuate;

- Homeowners’ ability to pay cannot be assumed; and

- Households may be asset-rich but cash-flow poor, such as those of pensioners (Solomon, 1983; AMEU, 1995; Mawhood, 1993; Reynolds, 2004; Van Ryneveld, 1990).

Excessive taxation may also result in tax evasion, reduced building activity, relocation to where taxes are lower (disinvestment) – as occurred in Johannesburg in the early 1990s (which we will explain in later chapters) – or even a loss of electoral support, as Margaret Thatcher found out in the British poll tax debacle of the early 1990s.

Ideally, municipalities should have a mix of taxes. This provides more options and greater flexibility to respond to changes in the economy, to expenditure needs, political imperatives and other factors. Additional taxes, subject to central government approval, then include:

- Personal income taxes;

- Corporate income taxes;

- Payroll taxes (such as the RSC levy which was abandoned by National Treasury [NT] in South Africa in 2005);

- General consumption taxes;

- Vehicle taxes; and

- Hotel occupancy taxes.

Bird (2000) identified six characteristics of a good local tax. Table 1.3 compares these against both older (Moak & Hillhouse, 1975) and more recent global assessments (Martinez-Vazquez, 2015) as well as an analysis undertaken by Bahl & Smoke (2003b) specifically on the South African sub-national revenue system. The big time gaps between the different studies are deliberate and useful in that they show that academic thinking on this issue has largely not evolved over time.

Source: Martinez-Vazquez, 2015; Bird, 2000; Bahl & Smoke, 2003b; Moak & Hillhouse, 1975

User Fees or Charges

When looking at user fees as an income stream, a key consideration is that utilities are usually constructed and developed by central government, and not local government. This is due to, amongst other things:

- The high levels of capital required;

- Cost reduction through economies of scale;

- Integrated planning of regional or national supply; and

- The need to assure standardisation.

A significant additional benefit is central government’s ability to cross-subsidise urban-rural tariffs, with rural tariffs being considerably higher per resident. Within this context, income from municipal distribution in developing countries is categorised by an implicit system of cross-subsidies from high- to low-usage households through block rates,[3] while industrial and commercial users (load pricing)[4] subsidise residential users (Bahl & Linn, 1992).

The World Bank deemed this inefficient, as under-priced services encourage over-consumption and waste – economic efficiency and not revenue generation should be sought – and on this basis it promoted the privatisation of public utilities (World Bank, 1988). Such a transition had to be managed carefully, however, as the removal of free or subsidised services would at times misguidedly be viewed as a pure “revenue-grab”. Then, in the absence of privatisation, municipalities needed to generate surpluses from electricity distribution, as it was a practical and reliable source of revenue, but they needed to comply with the abovementioned tenets of economic efficiency. Conversely, More (1999) argues that where there are high levels of inequality, a user fee, regardless of the level it is set at, excludes those at the margin. Public goods and services are meant for all residents, and equity should be prioritised over efficiency, by adopting a functionalist approach.

Looking back, Kessides et al. (2009) assessed the impact of privatisation and market-liberalisation reforms, under the neo-liberal approach of cost-reflective tariffs, on the affordability of public-utility services for low-income households in developing countries. In analysing 20 years of the effects of privatisation policies, the study found that the impact on the poor was grossly underestimated. More than anything, it meant that taxpayers defaulted on higher taxes not so much because they were unwilling to pay, but because they were not able to. The report concluded that an effective affordability analysis must be an integral part of every utility’s reform programme, especially during economic downturns.

Finally, with both taxes and user fees available as funding options to local government, it is useful to remember that albeit their similarity – in that proceeds are used to fund public-sector functions and services – they are different. Here, simplistic examples, such as personal tax (to fund general public-sector activities) and a parking entrance fee (to offset direct costs) are transparent, easy to understand, and therefore easily accepted. Confusion and outrage arise when proceeds are indirect and opaque, such as an excise tax on plastic packets to fund environmental programmes. As Duff (2004) summarises: “Benefit taxes and user fees are just one additional mechanism for government to raise revenue; and when used appropriately can deliver efficiency, accountability and fairness. They can however become regressive when used for pure public goods and redistributive transfers.”

National Transfers

If denied access to a wider range of revenue instruments, local government is legitimately entitled to a portion of national revenues through infrastructure grants and an equitable share arrangement. And the manner in which the share is calculated is often intended to address specific weaknesses and shortages; particularly given that the burden of providing for the poor who cannot afford services is unevenly distributed between municipalities. It is for that reason that this approach was adopted in South Africa, with the 1996 Constitution mandating local government to deliver specific services and functions, and then allocating an equitable share of national revenue to it. The formula – designed to be objective, transparent and beyond manipulation – is purposefully skewed towards smaller municipalities, which have a lower revenue-collection potential (as the poor cannot afford to pay for services, let alone taxes); and also to provide the poor (not all of whom are indigent) access to basic services (see FFC, 2012; NT, 2017).

Of course, while centralising revenue collection may have the advantage of simplifying taxation for government and citizens, it more often than not compromises local government, as it creates a level of dependence through national transfers, which tends to serve the priorities of national, not local government.

Direct Borrowing

As cities grow, so does the need for capital infrastructure projects. It is therefore necessary for central government to permit sub-national government to develop an effective borrowing mechanism, controlled through clear rules (Martinez-Vazquez, 2015).

1.4.3 The South African Model

Apartheid inhibited the movement of people, but after its fall, there were high urbanisation rates. This was expected, as was the pressure it would place on municipal revenue. It was less obvious, however, as to how the effects of this could be mitigated. South Africa, which received significant technical and advisory support from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) from 1990 on (Seekings & Nattrass, 2015, p.7), espoused a neo-liberal economic approach. It adopted business-friendly policies, which it was believed would ultimately lead to competitive markets and efficiencies, and in turn to greater prosperity. At municipal level, the proposed approach entailed:

- Privatising or outsourcing functions;

- Forging private-public partnerships;

- Focusing on cost recovery and value for money, and on customers rather than on citizens; and ultimately

- Focusing on promoting competition – which if introduced for services (electricity being a prime candidate), would decrease prices and make them more accessible to the poor.

Fiscal decentralisation also required maximising local revenue collection, to provide a level of independence from central government, which in turn strengthened democratisation. It would also afford the financial means for local government to execute its mandated functions, as well as greater transparency that allowed constituents to hold office bearers to account. Simultaneously though, local government’s limited capacity to directly raise revenue, coupled with central government’s overarching objective to maximise municipal self-reliance, created very particular tensions, many of which we will see playing out in the research that follows.

- The next chapter explains the government model adopted under the South Africa Act of 1909, which allowed for the continuation of municipal councils (Point 92, p.3) and which made their decisions binding unless “varied or withdrawn by Parliament of provincial council” (Section V, Point 93). Additionally, municipalities were directly accountable to their respective provincial councils (Section V, Point 85 [vi]). These institutional arrangements meant that municipalities did not have direct access to national government and had to go through provincial structures. ↵

- A progressive tax is defined as one whose rate increases as the payer’s income increases. That is, individuals who earn high incomes have a greater proportion of their incomes taken to pay the tax. A regressive tax, on the other hand, is one whose rate increases as the payer’s income decreases. ↵

- With increasing block tariffs, the rate per unit of electricity increases as the volume of consumption increases. Consumers face a low rate up to the first block of consumption and pay a higher price up to the limit of the second block, and so on until the highest block of consumption. ↵

- This is a pricing strategy wherein the service provider charges a higher price during peak demand times. Peak-load pricing allocates the cost of capacity across several time periods when demand systematically fluctuates. ↵