2

“The National Party is well aware of the enormous power wielded by a highly centralised state and is deeply concerned about the black majority assuming control of such an apparatus.” — Bekker in Heymans & Tӧtemeyer (1988, p.30)

2.1 Introduction

Municipal ESI developed in South Africa in the context of how government, and local government in particular, changed over time. This chapter thus traces the evolution of government in the country in order to provide context and an overview for the detailed analyses in later chapters. In this chapter, we look at the overall fortunes of local government during the three time periods selected for this book. We identify the prevailing national political dynamics for each period, together with how policy decisions were delegated to local government. We also assess the impact of these policy decisions on local government and the response to them. Throughout, we see how the consequences of decisions and actions taken at the higher level impacted local government.

2.2 Government Prior to 1910

In South Africa, local government with an elected council goes back as far as 1836, but its forms evolved differently, depending on particular British and Dutch influences (Tsatsire et al., 2009). Local government was initially influenced by the Dutch[1] (1652 to 1795 and 1802 to 1806) and then by the British (1795 to 1802 and 1806 to 1910), both of whom left deep impressions on the tradition and structure of local government. The former deeply impacted the system of rural and early town government, while the British influenced the development of urban municipal government, starting in the Cape Colony and spreading to Natal, Orange Free State and Transvaal. Vosloo et al. (1974) identify three forms of government during this period – rural, town and municipal. For our purposes, we limit our analysis to municipal.

The Anglicisation of institutions properly began with the British re-occupation of the Cape Colony in 1806 (see endnote 1). The Cape Municipal Ordinance was passed in 1836, which set up local government for towns in the form of a board of commissioners elected by households for a period of three years. Rates were levied annually by a public assembly. The Ordinance was essentially a framework within which municipal regulations were drawn up for differing organisations and powers, to meet the needs of each municipality. This home-rule measure allowed each local community to frame its own constitution in accordance with its own circumstances. The Ordinance was adopted by Natal (1847), and with minor variations, even by the two Boer Republics – Orange Free State (1856) and Transvaal (1877). Since it borrowed heavily from the British Municipal Corporations Act of 1835, it formed the basic framework for the subsequent introduction of typically British terms and practices such as mayor, town clerk, councillors, standing-committee systems, by-law powers, and the concept of a “municipal corporation”.

2.3 The Union of South Africa (1910–1948)

The South Africa Act of 1909 was an act of the British Parliament to create the Union of South Africa by merging the two Boer Republics (Orange Free State and Transvaal), which it had defeated in the Anglo-Boer War, with its two colonies (Cape and Natal). The Act allocated national government executive authority over provincial government, which in turn presided directly over local government (Government of South Africa, 1909, Section 85 [vi]).

2.3.1 Central Government

Central authority was vested in the national legislature (Parliament), its executive institutions and the judiciary. Based on the British Westminster system, Parliament was the sovereign legislative authority. The courts were not empowered to test the validity of parliamentary legislation adopted by constitutionally prescribed procedures. The House of Assembly was by far the most important unit in the legislative structure, with bills that appropriated revenue or imposed taxation. The political party with majority support gained control of the entire governmental structure. The judiciary was established and functioned in terms of acts of Parliament. Court hierarchy consisted of appellate, provincial, local and circuit divisions of the supreme courts, as well as special courts and a variety of local courts for the various magisterial districts, together with special courts for “Bantu”[2] matters (Vosloo et al., 1974).

The National Convention of 1908, to formulate consensus on the formation of the Union of South Africa, came under severe strain regarding the issue of non-white political rights. The Cape supported the extension of franchise rights to non-whites, but the other three future provinces of the Union favoured the restriction of all rights. The existing status quo was maintained in each province, on condition that the United Party would not permit non-white electoral candidates (Vosloo et al., 1974, p.33). This formalised racial segregation and entrenched it from thereon. For example, the Natives Land Act of 1913 limited black people to owning land in designated “reserves” which only made up 7% of the country. The allocation was increased to 13.7% in 1936 (Cameron, 1993, p.418). The Native Affairs Act of 1920 then created tribal-based district councils. The Natives Urban Areas Act of 1923 regulated the presence of black people in urban areas by creating townships[3] on the outskirts of towns. This was followed by the Local Government Act of 1926 denying citizenship rights to Indians (followed by an unsuccessful effort to repatriate them in 1927). Then, the Native Trust and Land Act of 1936 created African reserves, effectively formalising white and black rural areas (South African History Online, 2011).

2.3.2 Provincial Government

The provinces were a new creation under the Union. Provincial government, which was the second tier of government beneath central government, was created by the South Africa Act of 1909. Even though the Cape, Natal, Orange Free State and Transvaal retained their borders after the Union, they in no way kept any of their legislative powers. Provinces were designated specific functions and administrative duties by central government (Cloete, 1978, p.3), including managing schools, hospitals, roads and local authorities.

To fulfil their mandate, provincial governments were given legislative authority, but their ordinances would only be of effect if they were not “repugnant” to an act of Parliament (Government of South Africa, 1909, Section 86). The state president appointed an administrator for each province. The Provincial Administrator’s ultimate responsibility was to ensure policies applied were in line with those of central government.

2.3.3 Local Government

The formation of the Union brought together two colonial systems: Dutch and British. To simplify matters and promote co-operation, it was decided to retain the existing system of local government, which would henceforth fall under provincial government. Central government would from time to time pass acts impacting on local government, particularly regarding racial segregation, but ultimate control remained with provincial government. To manage local government, each province would pass local government ordinances that provided directives regarding the powers and duties of local authorities. All provincial ordinances were subject to the approval of central government. By-laws were subject to the approval of the Provincial Administrator. Under this structure, central government could control local government affairs without dealing with local government directly. Provincial government controlled how local government levied taxes, borrowed money, handled accounting procedures and appointed key personnel. Capital projects had to report to central Treasury.

Period Summary

Although the Union of South Africa introduced three levels of government, it was a unitary form of state, where central government had supreme power over the entire territorial state. Under this system, all other levels of government were subordinate – owing their creation and continued existence to central government – with the powers they possessed determined by it (Hanekom in Heymans & Tӧtemeyer, 1988, p.17). This centralised approach would be tightened even more as the National Party (NP) implemented its political and economic ideology.

2.4 The Rise and Fall of the NP and its Grand Apartheid Project (1948–1994)

2.4.1 Central Government: NP’s Policy of Separate Development

The rise of Afrikaner nationalism was marked by the accession to power in 1948 of the NP, based on its apartheid manifesto to formalise “separate development” along racial lines. Apartheid now contemporised, extended and codified racism in the context of a modern state.

With the NP essentially enjoying uncontested rule from thereon, a key consequence was that the Executive’s authority over time began superseding the legislature’s. Under the Westminster model, final authority lies with a sovereign parliament, but gradually Cabinet came to initiate all decisions, with Parliament simply endorsing them. By the 1980s, decision-making was highly centralised and effectively limited to the few securocrat members of the State Security Council (SSC) reporting directly to State President P.W. Botha, who also controlled access to the SSC. Before ending in 1994, the NP’s administrative rule can be broken down into three phases, which we examine next.

Phase 1: Segregationist Policies (1948–1960)

The main aim of segregation was to achieve maximum separation between whites and non-whites. This was brought about by three supporting objectives:

- To prevent further biological integration of the different races;

- To regulate points of contact amongst races; and

- To ensure total domination of the political system by excluding all non-whites from it.

The almost-endless list of punitive and inhumane laws targeting black people had significant negative financial, logistical and social implications for local governments, who were required to enforce them with impunity. This was to have long-lasting and huge consequences for local government in future, placing it under immense pressure to integrate hitherto under-serviced black areas when these were subsumed into neighbouring previously “whites-only” municipalities under South Africa’s first democratic government.

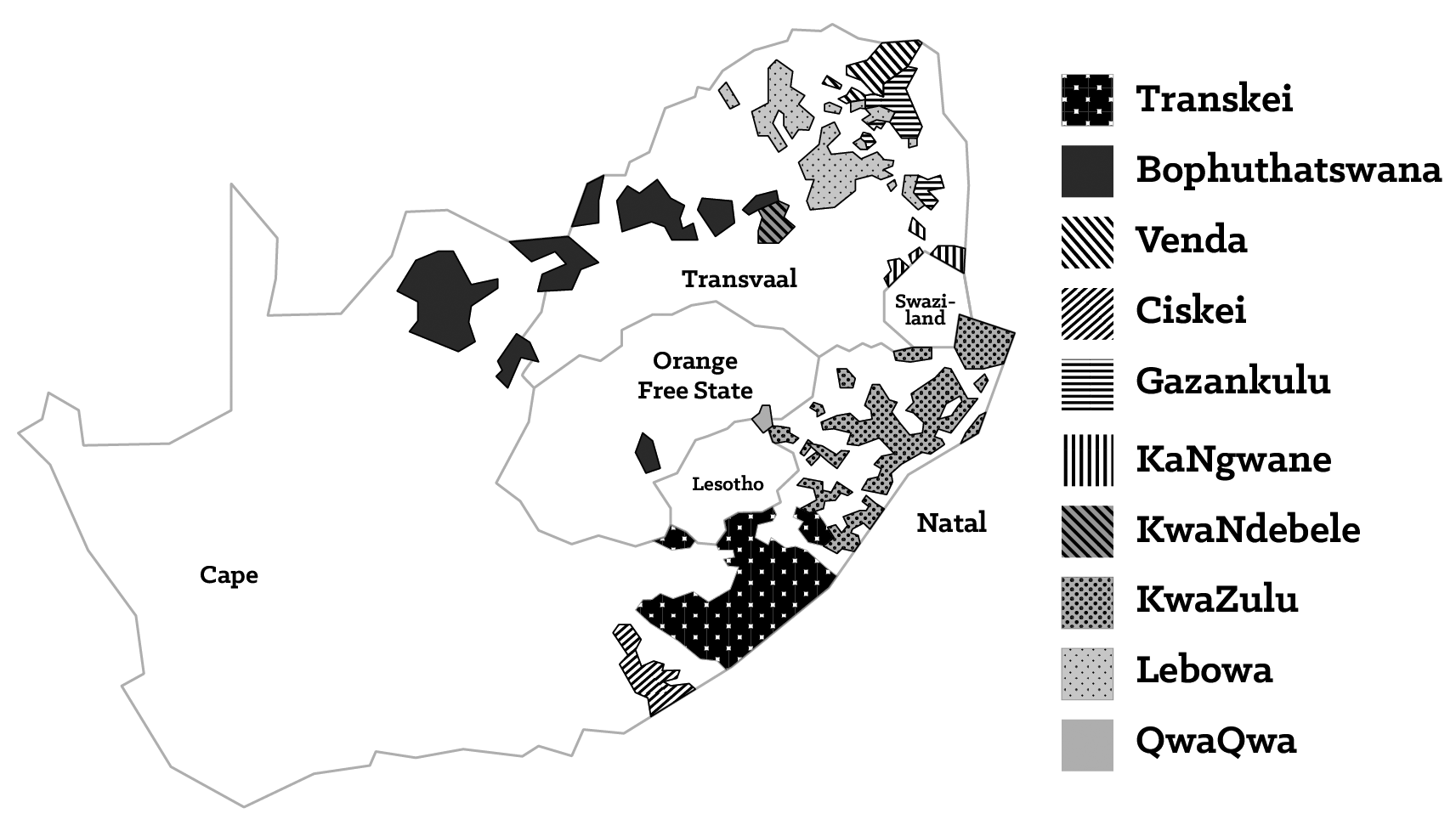

Phase 2: Developmental Phase (1960–1976)

Having excluded non-whites from all spheres of political, economic and public participation, the NP government turned its attention to creating alternative opportunities for them. The objective of this developmental phase was to create separate and subordinate national and local institutions for all non-white groups. The aim was then to build social and economic development areas within the territories non-whites were assigned to live in, which were called homelands, or Bantustans. To facilitate (false) “independence”, the people who were “transferred” to the homelands lost their own land, country and citizenship – essentially becoming foreigners in their own country. This was the primary difference between apartheid and segregation, as even in the USA natives who were clustered into Indian reserves were never excluded from their US citizenship.

During this period, the South African economy experienced high growth, with annual GDP growth between 6 and 8% during the 1960s.

The Soweto Riots (beginning on 16 June 1976) then provided a decisive historic turning point. Government finally realised that the Verwoerdian[4] myth of all Africans being “temporary sojourners” in white urban areas was untenable (Lemon in Smith, 2002, p.5). The economic and political costs of government policies were now evident, and to find solutions, several commissions of inquiry were formed. Tellingly, the Committee of Inquiry into the Finances of Local Authorities (Browne, 1980) distinguished between the “need to pay” and the “ability to pay” for municipal services amongst the three population groups, where White Local Authorities (WLAs) generated large surpluses, while coloured and Indian authorities did not – with little prospect of the situation improving over the 12-year forecast period to 1990.

In this, the Browne Inquiry distinguished itself from previous government reports, not because it noted the failure of the system, but because it formed the basis for the creation of Regional Services Councils (RSCs), detailed further on. Prior to Browne, the failure of the separatist system had been analysed but only noted by previous official inquiries, as an admission thereof would have challenged racial segregation.

Phase 3: Neo-Apartheid (1976–1994)

Under increasing international and local pressure to reform, and to stabilise the country, the NP realised that both political and economic changes were necessary. It acted by formally acknowledging and accepting recommendations for the maximum devolution of power to local authorities as a policy priority. Based on the findings of the Theron Commission (1976), reform was introduced through the Republic of South Africa Constitution Act of 1983, which abandoned the Westminster system and introduced the Tricameral Parliament, providing limited power-sharing to Indians and coloureds. Black people were excluded.

Having excluded the black population from the Tricameral system, but simultaneously recognising and accepting that they were permanent inhabitants in “white” areas, far-reaching reforms were introduced to change their status within urban areas (Christopher, 1997, p.318). Prior to 1982, black urban townships were administered by the national government’s Bantu Administration Board and provided limited services. As part of government’s reform process, where devolution became a priority, Black Local Authorities (BLAs) were created through the Black Local Authorities Act of 1982. These supposedly replicated the government structures administering white areas, so in theory were granted the same powers and authority. BLAs were now required to operate on a cost-recovery basis, i.e., the principle of financial self-sufficiency applying to all local authorities (Cameron, 2002; Bekker & Jeffrey, 1989; Solomon, 1983; Horowitz, 1994). But to finance themselves, WLAs raised revenue from property taxes and the provision of services such as electricity, water and garbage removal. National grants provided as little as 4.2% of capital and operational expenditure in 1978 (Solomon, 1983, p.28). This was not possible for BLAs for two reasons:

- They had almost no existing infrastructure from which to raise revenue; and

- Their residents (under apartheid) had very limited financial means.

As a result, BLAs resorted to significantly increasing rental and service charges. In response, residents protested, boycotted payments, and there was violence in many areas. Here, non-payment was not only an affordability issue, but also a form of political protest; with residents viewing BLAs as politically illegitimate (Tsatsire et al., 2009, p.137; Heymans & Tӧtemeyer, 1988; Poto in Heymans & Tӧtemeyer, 1988, p.101). Numerous black councillors resigned and many BLAs collapsed (Cameron, 2002, p.117).

To support BLAs, a regional services levy and a regional establishment levy were introduced. These were to be paid by white affluent commercial and industrial sectors and eventually became the basis of funding for the RSCs (Smith, 2002, p.4). RSCs were created in 1985 to serve as “proto-metropoles” made up of both WLAs and BLAs. Ultimately though, national government’s obsession with separate development led to the unnecessary duplication of infrastructure, services and manpower between WLAs and BLAs; all of which was iniquitous, inefficient and expensive. The reforms did not appease non-white citizens, and there was a marked escalation in political resistance, popular and violent township protest, and rural uprising. P.W. Botha resigned in August 1989, and F.W. de Klerk, already the leader of the NP, won the national elections that took place 23 days later, becoming state president in September 1989. Just four months on, he announced wide-ranging reforms effectively ending apartheid; heralding the country’s first democratic elections in April 1994.

The NP government immediately sought to reform local authorities. When De Klerk realised the country’s major (white) cities would be significantly larger once the townships were incorporated, he expanded the existing committee of inquiry, led by Dr Christopher Thornhill from 1989, that was investigating the total system of local government. A second report was also commissioned. The report identified five possible models, but by this time, the country was gearing up for its first democratic elections, and the findings were noted and shelved (Cameron, 1993). Dr Thornhill[5] rejected this view, stating that the findings formed the basis of the Local Government Transition Act (LGTA) of 1993, which ultimately led to local government becoming an independent sphere of government.

Period Summary

One of the final acts of the NP government may have been to eventually realise its long-held policy ambition of decentralising power to local government. Indeed, the extent to which the ruling party was sincere about decentralisation in the early- to mid-1980s may never be known, because it was in a constant state of national crisis defending apartheid. Thus, all reform measures came with central government veto power, which immediately generated mistrust, insincerity and legitimacy issues. As Bekker (in Heymans & Tӧtemeyer, 1988, p.30) put it: “The National Party is well aware of the enormous power wielded by a highly centralised state and is deeply concerned about the black majority assuming control of such an apparatus.” In the final analysis, government’s decentralisation programme was designed by the NP in an elitist fashion, to ensure that although it shared power, it retained control (Cameron, 1995, p.412). At the end of the day, the programme delivered little devolution and was limited to deconcentration and delegation (Cameron, 2002, p.119).

2.4.2 Provincial Government – Toeing the (National) Party Line

After winning the 1948 elections, the NP immediately focused on consolidating its position by centralising state control. Provincial government was restructured to comprise three elements: a Provincial Administrator; an executive committee; and a provincial council. The Administrator was appointed and dismissed by central government. Provinces presided over local authorities, who they regulated and controlled through provincial ordinances (Young, 1990, p.223). This structure again allowed national government to have its policies implemented with minimum interaction between it and local government. Fundamentally, the Provincial Administrator was local government’s decision-maker.

Provinces also oversaw local government finances, where strict control was exercised in line with national government requirements. This did not mean that provinces enjoyed any additional privileges though. Total power resided in the centre, and all provincial taxing abilities were curbed, making provinces almost exclusively reliant on funding transfers from national government. An additional example of national government constantly undermining its stated policy priority of devolution was the decision by National Treasury (NT) to supplant the provincial authorities in their oversite role of local government finances in the mid-1980s – citing local government inefficiency as the key reason, which if left unchecked could lead to excessive inflation that could “break the back of the economy” (Cameron, 2002, p.119).

2.4.3 Local Government – WLAs

To deliver on its election manifesto of separate development – which had to in effect be implemented at local government level – the NP moved quickly to centralise the powers and functions of local government even further. Existing regulations were repealed and replaced with new legislation to separate the different cultural groups. This side-lined the few non-white councillors in the Cape Province.

A policy of preferential access to jobs for white Afrikaners was put in place. This resulted in a gradual deterioration in the capacities and skills of the civil service, as powers were given to increasingly incompetent and less-qualified personnel. At the time, Afrikaners were (significantly) less educated than their English-speaking white colleagues. The NP’s policy of job reservation therefore successfully evicted English speakers, leading to a mass exodus of experienced and skilled people. This was reflected in the AMEU conference minutes during this time, which noted that experienced staff considered taking positions at municipalities in Southern Rhodesia (AMEU, 1950–1960).

In 1961, South Africa seceded from the British Commonwealth and issued a new Constitution that retained the existing levels of government. Control of local government remained under Provincial Administrations. Each local government had its own ordinances. By the 1970s, the objectives and functions of a typical large municipality in South Africa could be grouped into four categories:

- Social objectives (preventative healthcare [such as inoculations and health awareness], garbage removal, parks, firefighting, etc.);

- Physical objectives (housing services, town planning, water and electricity);

- Financial objectives (revenue collection, budgets); and

- General objectives (training).

Minor differences between cities remained. For example, Johannesburg operated a municipal public-transport service, which is still in effect, whereas Cape Town always outsourced the function.

Notable omissions from the list of functions were education (primary, secondary and tertiary), hospitals (including child welfare, healthcare for addicts, and care for the aged) and policing. Table 2.1 lists the non-municipal functions in 1977 and shows which level of government was responsible for them. This arrangement remained intact until the 1996 Constitution, which came into effect after the country’s first democratic elections and is covered in greater detail in later sections.

Source: Adapted from Hammond-Took (1977)

2.4.4 Local Government – BLAs

The Natives Urban Areas Act of 1923 allowed for segregated urban areas and required black advisory committees to advise WLAs responsible for administering black townships. The black advisory committees had no powers to act, and all decisions affecting the townships were made jointly by the township’s WLA and the national Department of Native Affairs.

In 1971, national government took the administration of the councils away from WLAs and gave it to the newly created Bantu Affairs Administration Boards, which black councils had the option of joining. Taxation and finance remained with WLAs, meaning that townships had very limited economic activity and thus little revenue to build infrastructure and provide services. The black community in the townships mobilised in protest, and the black civic organisations that had by now formed, successfully convinced residents not to pay rent or service charges, making townships financially unsustainable. Finally, national government introduced BLAs (through the Black Local Authorities Act No. 102 of 1982). These reported to their respective Provincial Administrators, with policy in the form of legislation coming from central government, and the principle of financial self-sufficiency applying.

The eventual formation of RSCs through the Regional Services Councils Act of 1985, to cross-subsidise infrastructural development in BLAs through levies imposed on commerce and industry in WLAs, and to co-ordinate supply of services, now meant that RSC levies could be used to fund 21 functions. These included bulk water and electricity supply, sewerage, roads, and the maintenance of infrastructure, services and facilities. The tax rates charged were determined by the Minister of Finance, and it was compulsory for each RSC to spend the proceeds on specific functions – prioritising areas where the greatest need existed, i.e., black townships (Cameron, 1993; Heymans & Tӧtemeyer, 1988; Smith, 2002; Bekker & Jeffrey, 1989; Solomon, 1990).

As the Financial Mail put it: “Perhaps the most important result of this Act will be an effective redistribution of income, wealth, development and influence in a region from white to black, coloured and Indian communities, with the direct participation of these communities.”

Indeed, RSC revenue did provide funding for much-needed infrastructure in the areas where it was lacking most, and was effective in that over 80% of the annual budgets of the various RSCs were spent in black areas (Cameron, 1993, p.424). However, problems persisted. The inability of BLAs to generate meaningful revenue meant that a greater proportion of the funding had to be allocated to subsidise BLA operations, or more accurately, to keep bailing them out, which reduced capital infrastructure spend. Regardless of these drawbacks, the RSC mechanism proved to be resilient, and levies used to fund local government were only eliminated in 2005.

2.5 A New Constitution, Spheres of Government and Democracy (1993–1996)

By 1990, the NP had committed to democratic elections and the negotiation of a new constitution with all political parties. The Interim Constitution was then negotiated in 1992 and 1993 to support the transformation period needed to end apartheid, and provided the basis for the Final Constitution.

2.5.1 Interim Constitution

The NP insisted on constitutional power-sharing to protect minority rights – allowing for a Government of National Unity (GNU), wherein political parties gaining more than 20 seats in the National Assembly would receive Cabinet seats. The GNU was formed after the April 1994 national elections and would exist until the Final Constitution had been agreed. The Interim Constitution made provision for a three-tier system of national, provincial and local government. Under it, there were now nine provinces instead of four.

In many ways, the NP’s strategy to protect minority interests, and more specifically its white electorate’s interests, was manifested through maximum decentralisation to local government. Realising that it would lose the national elections, the NP recognised that winning local elections in existing and economically influential WLAs would result in strong local government that could provide some checks and balances to a black-controlled government. Conversely, the ideology of the ANC called for a highly centralised approach, which it believed was a more effective form of administration and was seen as a mechanism more likely to ensure redistribution of wealth and the reversal of apartheid inequities.

2.5.2 Final Constitution

This Constitution is the supreme law of the Republic; law or conduct inconsistent with it is invalid, and the obligations imposed by it must be fulfilled. (Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996, Chapter 1: Section 2).

The Final Constitution adopted the principle of co-operative government (Chapter 3: Section 40), where government consists of three spheres (national, provincial and local) which are “distinctive, interdependent and interrelated”.

Section 156.1 gives local government the executive authority to administer services listed in Part B of Schedule 4 and Part B of Schedule 5, which include electricity and gas reticulation (Schedule 4, Part B). The net effect was that local government now has constitutionally guaranteed functions; with electricity reticulation[6] being one.

Although provision was made for inter-governmental grants from national to provincial and local government, the principle of self-financing for local government was maintained. Section 229 (“Municipal fiscal powers and functions”) thus allows municipalities to impose: “a. rates on property and surcharges on fees for services provided by or on behalf of the municipality”; and, “b. if authorised by national legislation, other taxes, levies and duties appropriate to local government …”.

But no municipality may impose income tax, VAT, general sales tax or customs duty.

2.6 New Beginnings? (1997–2014)

2.6.1 Establishing Democratic and Decentralised Local Government

Removing well-entrenched, decades-old structures was not seen as a straightforward task. Communities, services and local government skills were clustered along racial lines. Transforming local government would require the demarcation of municipal boundaries to make them inclusive and representative, and in order to redistribute political power. Such a process would inevitably result in winners and losers, making it a highly emotional and contested issue.

2.6.2 Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) and Growth, Employment, and Redistribution (GEAR)

The RDP was adopted by the GNU after the 1994 elections, to be implemented by civil society in addressing issues of social inequality and justice. The plan was structured to balance, on the one hand, the funding needed to pay for urgent and very necessary reconstruction and development, and on the other, the imperative of growing the economy to provide the financial resources needed to pay for the programme.

Just two years later, the ANC introduced the GEAR initiative, whose stated objective was to build on, and not replace, the principles of the RDP (Manuel, 2006; Gelb, 2006, p.2). This viewpoint has however been hotly debated, with GEAR seen as having a far more centrist economic foundation and being yet another, further, move away from the ANC’s left-of-centre ideology (Weeks, 1999, p.796). GEAR’s five-year programme targeted a GDP growth rate of 6% in its final year, with an average of 4.2% over this period (1996–2000) – the minimum rate needed to construct a competitive economy required to create 400 000 jobs per annum, address inequality and extend service delivery. The economic policy of GEAR explicitly emphasised:

- Fiscal austerity;

- Deficit reduction;

- Pegging taxation and expenditure as fixed proportions of GDP;

- Cutting back on government consumption expenditure; and

- Keeping wage increases in check.

The state would henceforth play a stronger role in co-ordinating fiscal and budgetary policy. Over its five-year duration, GEAR would reform accounting practices, financial management and the budgetary process and intergovernmental fiscal system. Capital payments to municipalities were fused into the Consolidated Municipal Infrastructure Programme (1996) and the equitable-share formula for local government, introduced in 1998, was to be used to fund the roll-out of services to indigent households.[7] At the time, changes to municipal finance under GEAR were introduced simultaneously with the drafting of the White Paper on Local Government (Powell, 2012; Weeks, 1999).

2.6.3 Green and White Papers on Local Government

Introducing democracy to local government would require a complete overhaul of the existing system. This could not be achieved all at once, and certainly not in a fragmented and dysfunctional system. In order for negotiations to take place, stability had to be maintained, so it was essential that service provision continue. To this end, a five-stage process was envisioned:

- Stage 1 would involve formulating the overall vision, goals and direction of key issues;

- Stage 2 would require the relevant ministry to formulate green and white[8] papers;

- Stage 3 would necessitate that the Green Paper be debated in Parliament; and with consensus, a white paper would be issued by the ministry;

- Stage 4 would involve the appropriate ministry formulating the law (bill) to achieve the White Paper policy objectives; the draft bill would then be reviewed by Parliament, the public and Cabinet; and only when the final bill was signed by the president, would it become law; and

- Stage 5 would entail the implementation and/or subordinate legislation providing further detail; with all three spheres of government responsible for implementing government policy.

The Green Paper on Local Government was released in October 1997 and the White Paper just five months later, in March 1998, with the short timeframe between the two pointing to the envisioned approach being compromised. We now look at the two primary outcomes before assessing the White Paper itself.

Developmental Local Government

Four developmental outcomes were identified:

- The provision of household infrastructure and services;

- Creation of liveable integrated cities, towns and rural areas;

- Local economic development; and

- Community empowerment and distribution.

The first outcome dealt with the traditional functions of local government – service delivery – while the remaining three were new additions. The White Paper’s intention on services (Ministry of Provincial Affairs and Constitutional Development, 1998, p.27) is of primary relevance to this study and is therefore interrogated in more detail.

The Paper’s priority and starting point was the provision of basic services to those who had little or no access to them. The envisaged funding for these capital projects would come from grants from the consolidated municipal infrastructure programme, cross-subsidisation of existing services, and private-sector involvement. Operational costs would be financed from the equitable share of national revenue to which local government is entitled. To ensure sustainability, the level of investment would need to match the ability of the various communities to pay for these services.

Achieving the four developmental outcomes would require significant changes, and the White Paper identified three interrelated approaches to assist municipalities:

- Integrated development planning and budgeting;

- Performance management; and

- Working together with local citizens and partners.

The first tool, integrated development planning, is a mechanism for short-, medium- and long-term planning. Integrated Development Plans (IDPs) are incremental plans which recognise that not everything can be planned in year one and that circumstances change. They also provide a comprehensive framework for municipalities to identify and plan their developmental mandates. In addition, the White Paper unequivocally states that IDPs must be developed and managed internally so as to strengthen strategic planning, build organisational partnerships between management and labour, and enhance synergy between line functions.

The second tool, performance management, then seeks to ensure that the plans being implemented are having the desired impact and that resources are used efficiently. Both national (fixed) and local (relevant) key performance indicators are proposed, providing national government with an assessment tool of how local government is performing.

The third and final tool, working with local citizens and partners, is a key tenet of decentralisation; and here, four different levels of interaction with the electorate and stakeholders were identified:

- Political accountability (voters);

- Input into planning processes (citizens);

- Quality and affordable services (consumers); and

- Mobilising resources and providing assistance (partners).

Co-operative Government

The White Paper reinforced local government’s elevation to a sphere of government; no longer subordinate to, and a function of, national and provincial government. The Paper recognised the complex nature of government and the need to strike a balance between independence and co-operation. National policies from various ministries were summarised, the most relevant of which for this book was the one provided for the then-Department of Minerals and Energy (DME). The proposed transformation of the electricity industry was noted. More specifically, how this reform would impact on municipal and Eskom reticulation activities was recognised:

- Eskom and MEUs were distributing to different parts of the same municipality;

- Municipalities were losing their licences, as they were not paying Eskom for their bulk electricity supply accounts;

- The envisaged Regional Electricity Distributors (REDs) would combine Eskom and municipal reticulation into autonomous structures; and

- The extent to which municipalities – especially larger ones – relied on electricity sales for revenue and cashflow was recognised, thereby acknowledging the established practice of cross-subsidising non-viable municipal services from “municipalities’ profits on electricity supply” (Ministry of Provincial Affairs and Constitutional Development, 1998, p.45).

To compensate for any potential loss of revenue from restructuring, the White Paper envisaged that “Municipalities will be allowed to levy a tax on the sale of electricity which should in aggregate improve their income from electricity” (Ministry of Provincial Affairs and Constitutional Development, 1998, p.45). Its summary then concluded that details of the proposed restructure were still being discussed and that local government should participate to ensure its interests were represented.

2.6.4 Assessment of the White Paper on Local Government

The White Paper was keenly anticipated, but once most had examined it, they felt that although it was well written, it failed to recognise the magnitude of the task at hand. Importantly, it did not provide an adequately detailed policy framework for municipalities to adopt their most basic objective – service delivery. The biggest criticism was that the Paper failed to acknowledge local government’s state of crisis; and on that basis, it would be difficult to deliver on the proposed outcomes, let alone the provision of basic services to municipalities’ inhabitants. And although the Paper raised and recognised many of the issues plaguing local government, the concluding statements to each showed little appreciation for the magnitude of the problem:

- On finance (p.17), it reckoned that “many municipalities are financially stable and healthy despite these problems”; and

- On administration (p.17), it conceded that “front-line workers remain de-skilled and disempowered”, but it failed to provide a solution other than that support and investment were required.

The fact that the Paper appeared to gloss over fundamental weaknesses in local government prompted strong words. Simkins (1998) published an article titled “Paper a Muddled Response to Critical Queries”, focusing on its financial aspects, articulating the failings, and concluding that an opportunity had been missed. Bernstein (1998, p.302) found the description of the state of local government finance “casual and inadequate”. Savage (2008, p.288) recognises the failings of the paper and points to:

- A lack of available data at the time;

- The impossibility of fully anticipating the effects of the transformation programme; and

- Policy debates reflecting “irresolvable tensions”.

On development, the policy messages were seen as “contradictory and lacking in substance” (Schmidt, 2008, p.22). Comparing his analyses of democratic decentralisation programmes in countries in Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe and South America, Manor (2001, p.8) states he has “never seen such a wildly unrealistic set of tasks imposed upon local authorities” as found in the White Paper. The most damning conclusion drawn was that the White Paper and comments by national ministers at the time “de-elevated” local government from a sphere to a tier; encouraging centralisation rather than decentralisation of power and functions (Bernstein, 1998; Siddle, 2011; Schmidt, 2008; Manor, 2001).

2.6.5 Performance of Local Government Since 1998

Restructuring Local Government

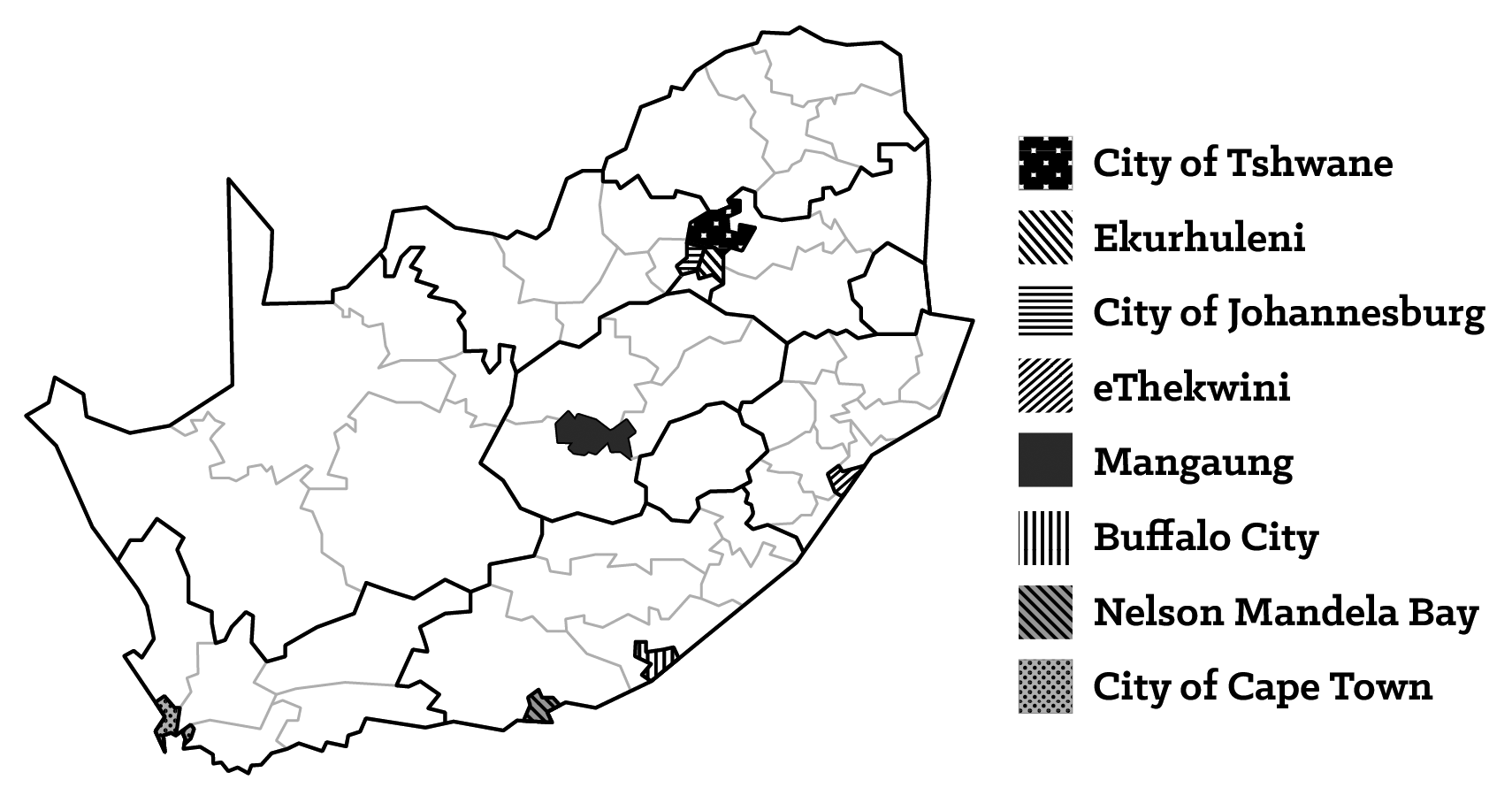

The Municipal Demarcation Act (1998) and the Municipal Structures Act (1998) created a demarcation board to determine the boundaries of new municipalities (278 were created) and established structural, political and functional institutions for municipalities. To meet the requirements of the 1996 Constitution, which called for “wall-to-wall” municipalities, three categories of municipalities were introduced based on single- and two-tier local government:

- Single-tier local government, with Category A municipalities (Metropolitan Municipalities) with exclusive municipal executive and legislative authority in their area; and

- Two-tier local government, with Category B municipalities (Local Municipalities) and Category C municipalities (District Municipalities), where a Category C municipality shares jurisdiction with several Category B municipalities.

Figure 2.2 shows the country’s provincial and district borders and the eight Metropolitan Municipalities (Category A). Table 2.2 lists the categories and their respective number of municipalities.

As early as 1998, local government policy and institutions demonstrated the friction of competing national objectives. While the Constitution and RDP mandated local government to undertake capital infrastructure spending for service delivery, intergovernmental fiscal policy would require compliance with GEAR targets, resulting in a reduction in spending and the centralising of policy with NT.

By 1998, redistribution was deemed a national (not local) responsibility, and the withdrawal of the RSC levy was proposed (it was eventually abolished in 2005). This further limited the role local government could play. The equitable-share formula predicted that only 10% would be needed. The remaining 90% would be self-financed, which immediately meant that local government was underfunded, and although transfers were made to local government in lieu of the RSC levy, they were lower amounts.[9]

Finally, the Profession of Towns Clerk Act, Repeal Act (1996), for reasons of transformation, allowed politicians to appoint municipal managers. Previously, these officials had to be qualified professionals. This created an unregulated environment and compromised performance, as politicians took centre stage. It manifested in a failure to recognise professional municipal officers. The lack of professional development, together with job insecurity, led to high turnover rates and low barriers to entry (Mashatisho, 2014, p.5). This view is shared by Mr M. Pomeroy, head of MEUs at the Johannesburg Municipality, who resigned in 1996 (he had joined in 1959) citing constant political interference.[10]

Recognising the damage that the Act was causing, NT reversed it in 2007, but by this time, local government was being asked to do more with less, due to its declining skill base. Of seemingly even greater consequence was the loss of skills and structure which had been built up over many decades. In hindsight, a more orderly transformation process should have been considered.

Local Government Under President Thabo Mbeki (1999–2008)

Under President Mbeki, the new government identified two priorities to complete the restructuring of local government. The first was the establishment and induction of the newly formed municipalities by 2005. However, delays were immediate, and it was evident that the process had been grossly underestimated and would take much longer than expected. The second priority was the completion of new policy, legislation and frameworks, which included:

- Free Basic Services (FBS): Pre-defined free quantities of water, electricity, sanitation and garbage-removal services for the indigent;

- The Municipal Systems Act (2000): Regulating planning, service delivery, performance monitoring and public participation;

- The Municipal Finance Management Act (2003): Financial management, accounting, supply-chain management, reporting and budgeting; and

- The Municipal Property Rates Act (2004): Property evaluations and taxing.

Re-elected in 2004, Mbeki’s second term came with contradictions. On the one hand, the ANC extended its domination across all three spheres of government and took control of all nine provinces. According to the ANC, this represented an overwhelming expression of confidence in the party, specifically from the poor (Mbeki, n.d.). On the other hand, a tactic that the ANC had used so effectively during apartheid now began being applied to them. After a decade-long break, mass protest action (excluding industrial action) resumed and became a regular occurrence.

Recognising that inequality was growing, Mbeki identified local government as a major role player in his corrective strategy. In this, the inter-governmental relations framework (2005) aimed to improve and promote relations between the three spheres of government, by:

- Formalising interaction and communication between national departments and local government;

- Executive mayors being given direct representation in provincial inter-governmental forums; and

- District and local executives accessing a direct forum to improve their communication and relations.

In this context, the successful bid to host the 2010 FIFA World Cup required major infrastructure projects – precisely what was needed to dent the country’s stubbornly high official unemployment rate of over 20% by creating new jobs and opportunities. However, national government overestimated local government’s ability to deliver what was required, grossly miscalculating the effects that transformation and other issues had had on local government performance. A two-year intervention (2004–2006) was thus devised. Project Consolidate, and Siyenza Manje (2006–2009; meaning “We are doing it now”), became formalised programmes of national and provincial government oversight of local government performance. This was provided for and required by the Constitution, but it had until then not been exercised. As a result, 1 124 technical experts were sent to 268 municipalities by 2008 to support financial management and infrastructure planning and training (Powell, 2012). Regrettably, these efforts amounted to little, and in his 2009/10 assessment, the auditor general stated: “despite an abundance of technical tools to support municipalities … the results were only fractionally better than the previous year”.

After the two-year intervention of Project Consolidate, and after the initiation of Siyenza Manje, Cabinet adopted the Five-Year Strategic Agenda (5YSA) in 2006. Following a review of the first five years, it was found that expectations for transition were too ambitious and that the mismatch between national policy objectives and local government’s ability to implement them was widening. Three imperatives were identified:

- Local government would have to improve performance and accountability;

- A national capacity-building initiative was needed to improve skills; and

- All three spheres of government required improved policy co-ordination, monitoring and supervision.

Simultaneously, the populace had started losing patience, and protest action had gathered momentum. Commonly referred to as “service delivery” protests, because their cause was the perceived lack of service delivery, they became seen as a common revolt against “uncaring, self-serving, and corrupt leaders of municipalities” (Alexander, 2010), and gained notoriety for their remarkable ability to quickly escalate into violence and the destruction of property. Underpinning all the protests was a growing frustration at the injustice of persistent inequality (Nleya, 2011; Reddy & Govender, 2013; Alexander, 2010).

In response, the final act of the Mbeki government was to initiate a review of the White Paper on Local Government and to draft a white paper for provincial government; with a discussion document being developed to discuss retaining, abolishing or reforming the provincial system. The process was however disrupted when Mbeki lost the ANC leadership in 2007 and resigned in 2008.

Local Government Under President Jacob Zuma (2009–2016)[11]

President Zuma commenced immediately with a ministerial name change: the Ministry of Provincial and Local Government would henceforth be known as the Ministry of Co-operative Governance and Traditional Affairs (COGTA). All existing programmes were put on hold and the Local Government Turnaround Strategy (LGTS) was introduced. It was based on an assessment of local government and found that the system as a whole “showed signs of distress” and was characterised by:

- Huge service-delivery backlogs;

- Increasingly violent service-delivery protests;

- A breakdown in council communication with and accountability to citizens;

- Political interference;

- Corruption;

- Fraud;

- Poor management;

- Factionalism in parties; and

- Depleted municipal capacity.

The LGTS required all municipalities to adopt turnaround strategies in the IDP, but as with previous attempts, the LGTS yielded poor results. An interim report by Deloitte (2012, p.4) noted, among other things, that:

- Funding for proposed interventions was limited;

- With limited capacity to undertake existing functions, how could it be possible to turn things around?;

- Interventions to date were “quick fixes” to achieve compliance, and not properly conceived long-term solutions; and

- Municipalities were suffering from transformation fatigue, with cynicism about yet another intervention.

Research conducted by the Institute for a Democratic Alternative for South Africa (Idasa)[12] in 2011, found that as many as 80% of respondents were dissatisfied with the municipal services they received (Reddy & Govender, 2013, p.86).

Zuma then secured a second term, and in his State of the Nation Address in 2014 reiterated government’s commitment to developmental local government, stating that despite achievements, “much still needs to be done”. The new COGTA minister, Pravin Gordhan, previously minister of finance, seized upon the recently published National Development Plan (NDP) and launched the Back to Basics (B2B) campaign. Municipalities were rated “Top”, “Middle”, or “Bottom”; with each category representing roughly one-third of municipalities.

The campaign identified characteristics of municipalities in each category and how Bottom and Middle municipalities could improve and stabilise. B2B is noteworthy for its simple, direct approach, and its honesty, in targeting the Middle and Bottom tiers. Gordhan was then moved back to his original post of finance minister in December 2015, and while the status and progress of B2B has appeared to fade from public consciousness, the electorate finally spoke at the 2016 municipal elections. Here, the ANC retained its overall majority nationally, but lost significant ground to the opposition parties overall. It also lost its majority in four (of eight) metropolitan councils:

- Nelson Mandela Bay, Johannesburg and Tshwane acquired opposition mayors under multi-party coalition agreements; and

- Ekurhuleni is run by the ANC under a coalition, as the party did not secure an outright majority.

Cape Town was retained by the Democratic Alliance (DA) opposition party.

As Brock (2016) put it: “Angry about corruption, unemployment and shoddy basic services, many ANC supporters have turned to the opposition Democratic Alliance (DA) – making a switch that was unthinkable only a few years ago when the party was still seen as the political home of wealthy whites.”

An opposition party take-over guarantees nothing though, as many post-2016 events have proved, but closely-contested elections do however serve to strengthen democracy and accountability – two primary ingredients of decentralisation – with the next local government elections coming up in 2021.

- In 1652, the Dutch established a trading post on the Cape Peninsula which quickly developed into a colony, and which was to become Cape Town. The Dutch ruled until the British seized the colony in 1795 after the Battle of Muizenberg. The Dutch recovered the territory after the Treaty of Amiens in 1802 but it was surrendered back to the British in 1806. ↵

- “Abantu” (or “Bantu” as it was used by colonists) is the IsiZulu word for “people”. The South African government replaced the word “Natives” with “Bantu” in the 1960s, but as the word became despised by black people due to its association with apartheid, the government slowly started replacing it with “Black” from the mid-1970s. For more details, see https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/defining-term-bantu (accessed 10 February 2021). ↵

- Also referred to as “locations” by South African urban planners. The word “township”, before the apartheid regime, was used for each new planned urban set of plots (erven). ↵

- Hendrik Verwoerd was the South African prime minister who served from 1958 until 1966 (assassinated) and was one of the primary architects of apartheid. ↵

- Interview with the author, 13 May 2016. ↵

- In the context of the Constitution, this is limited to municipal distribution. ↵

- According to Fanoe and Kenyon (2015): “Section 227 of the Constitution stipulates that: ‘Local government and each province is entitled to an equitable share of revenue raised nationally to enable it to provide basic services and perform the functions allocated to it.’ The Equitable Shares are unconditional in nature … Formulas are used to divide the provincial equitable share among the 9 provinces and local government equitable share among the 278 municipalities to ensure that allocations are based on objective data and cannot be influenced by bias.” ↵

- A remnant of the British system, a green paper is a discussion document developed by government and experts, and identifies key issues, as well as proposes alternatives. Once accepted, a white paper is issued which is a statement of intent and detailed policy plan. ↵

- Dr Thornhill, interview with the author, 13 May 2016. ↵

- Interview with the author, 27 January 2017. At the meeting, Mr Pomeroy stated that this practice continued after his resignation; most of his colleagues left. His replacement was not sourced from the department, but was a senior official who was without a portfolio at the time. This impacted staff morale, as deserving and competent employees were overlooked. It also resulted in declining performance of the undertaking, as the new head was inexperienced. ↵

- President Zuma’s second term was scheduled to end in 2019, but the study limits its research to 2016. His term then ended in February 2018 when, like his predecessor, he was recalled by the ANC. ↵

- Idasa, a long-standing and highly respected NGO working on democracy and governance, shut down in 2013 after 27 years, due to a lack of funding. Its reports are no longer available online but are still regularly cited. ↵