Mia Moody-Ramirez

When I first began hearing news about critical race theory (CRT), I wondered how it had become such a hotly debated topic in the political arena. Echoing the sentiments of other state legislatures across the country, Texas Republicans advocated limiting what public school teachers may teach regarding the nation’s historical subjugation of people of color.

I hoped the debate would subside; however, it has not. Two bills were introduced in the Texas Legislature to spotlight the teaching of CRT, a concept that views race as a social construct and examines how racism has shaped legal and social systems.

The Senate passed Senate Bill 2202 in May 2021.[1] The bill authored by Sen. Brandon Creighton, R-Conroe, primarily addresses the following:

-

bans teaching that “one race or sex is inherently superior to another race or sex;

-

an individual, by virtue of his or her race or sex, is inherently racist, sexist, or oppressive, whether consciously or unconsciously.”[2]

The bill also states a “teacher may not be compelled to discuss a particular current event or widely debated and currently controversial issue of public policy or social affairs.”

What is Critical Race Theory?

So, what exactly is CRT? The theory emerged in the 1970s and 1980s as an outgrowth of the civil rights movement. The Critical Legal Studies ideology advances an understanding of law as deeply connected to lived experiences and social power—particularly for marginalized groups.[3]

Legal scholars Derrick Bell, Kimberlé Crenshaw and Richard Delgado, among other scholars, studied race, racism and power and placed them in a broader context to include economics, history and other factors.[4]

Parker and Lynn (2002) characterize CRT as incorporating three goals:

a) to present storytelling and narratives as valid approaches through which to examine race and racism in law and society;

b) to argue for the eradication of racial subjugation while simultaneously recognizing that race is a social construct; and

c) to draw important relationships between race and other axes of domination.

Delgado and Stefancic highlight the following tenets of CRT:

-

Racism is “ordinary” in American culture thus is difficult to address because it is not acknowledged;

-

An “interest convergence” because racism advances a large segment of society; therefore, there is little incentive to eradicate it;[5] and

-

A “social construction” which highlights that race is product of social thought and relations.[6]

Additionally, the two make the case that CRT expands beyond race, racism and power to also examine the economics, history, cultural context, as well as the emotional impacts of race, racism and power in understanding social and political issues.

A primary goal of CRT is to re-center inquiry and experience from a marginalized perspective. CRT is concerned with consciousness-raising, emancipation and self-determinism. As a CRT tactic, Derrick Bell advocated for using “interest convergence,” which maintains that the “majority group tolerates advances for racial justice only when it suits its interests to do so.”

Interest convergence is the “merging” of interests between what persons of color seek and what dominant policymakers perceive they or the country needs. When conditions change and the difficulty of implementing change increases, rationales are found to justify change. Bell explains this strategy was exemplified when Brown v. Board of Education was decided in 1954. Civil rights lawyers had worked diligently for 20 years to overturn the “Separate but Equal” doctrine of racial segregation.

Bell suggested the civil rights movement ultimately succeeded because it had moral force and a powerful, well-organized grassroots effort that altered the understanding of a voting majority in Congress as enlightened self-interest and in the nation’s interest. The Supreme Court’s decision, urged by the Justice Department, was intended to improve U.S. image abroad, where we were competing with communist nations for the hearts and minds of peoples of color who were emerging from long years of colonial domination.

Several award-winning authors have addressed racism using a CRT lens. Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility and Ibram X. Kendi’s How to be an Antiracist address the issues of race, privilege and oppression. They highlight how descendants of the enslaved have continued to deal with systemic racism.

What CRT is not:

-

A new theory;

-

A catch-all term for what some see as divisive efforts to address racism and inequity in schools;

-

Implicit bias training;

-

A synonym for diversity, equity and inclusion;

-

A clandestine way to spread racist rhetoric; or

-

An endorsement of the idea that America is a colorblind and postracial society (particularly after former president Barack Obama was elected president of the United States).[7]

Why Now?

In the United States, we are in the midst of two crises—a racial reckoning and the COVID-19 pandemic. CRT scholars often argue that social relations are fundamentally race-related due to legal, social and historical traditions.

Following George Floyd’s death on May 25, 2021, America reached a tipping point. In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, protests took place around the world.

Floyd, accused of using a counterfeit $20 bill, had his neck compressed by an officer’s knee while in handcuffs for roughly nine minutes before later dying. Numerous other instances of racism against Black people in the country have led to demonstrations against police brutality and systemic institutional racism that many feel have gone unchecked for decades.

Social media platforms were instrumental in fueling grassroots efforts that included protests because of the ease of coordination, speedy exchange of information and low expense to launch a social media campaign. Common CRT tenets such as “colorblindness doesn’t exist;” and the “permanence of racism” (Bell, 1992; Crenshaw, 1991; Ladson-Billings, 1998) are often illustrated in the content of social media platforms. Citizens use racial stereotypes as tools to characterize the victims of police brutality negatively (e.g., Drummond, 1990; Entman & Rojecki, 2000; Dates & Barlow, 1993; and Pilgrim, 2012).

Citizens are able to organize support for protests using social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram very easily. In Waco, for example, several teenagers recently organized a peaceful demonstration for George Floyd in one night using Snapchat. It was very successful. Individuals may also share videoclips of demonstrations on social media, which is key in facilitating change.

Social media are very powerful, and we are seeing that citizens can make a difference using them to tackle issues in race relations. User-generated content levels the playing field, eliminates gatekeepers and offers a solution for marginalized groups that want a tool to facilitate grassroots efforts. Some movements that have been popularized on social media are the Arab Spring, Black Lives Matter, #MeToo, #ICantBreath, #HandsUpDontShoot, #BringBackOurDaughters and many others.

Social media platforms have played a role in sharing counter-narratives. The #CrimingWhileWhite campaign highlighted how Whites often receive little or no police attention or sanctions for their alleged criminal behaviors. Twitter posts indicated that race played a major factor in the lack of arrests for criminal offenses.

According to cultural and social issues writer, Tierney Sneed of U.S. News & World Report, the hashtag #CrimingWhileWhite—apparently started by former Daily Show writer Jason Ross—became popular as White users confessed crimes they committed for which they faced little or no punishment from the police (Sneed, 2014).

After Floyd’s death, an important time in history occurred where Americans began weeding out racist symbols in American culture: Major companies began rebranding their products perceived as racist. Confederate statues were removed. The AP Stylebook recommended the capitalization of the letter “B” for Black people. Streets were renamed Black Lives Matter Blvd. In addition, Minneapolis dissolved its police department altogether. That is more progress in a few weeks than we have seen in hundreds of years.

However, this progress was met with traction. The removal of statues, in particular, was a sticking point. Many groups view it as erasing history. Counter-arguments highlight the idea that while statues may represent historical content, they are not history. In other words, removing a statue does not equate to not teaching about its historical significance in school. Instead, statue removal symbolizes rejecting what the statue represents in the present day.

Stephen Sawchuk[8] in Education Week states that much of today’s criticism of CRT stems from The New York Times’ 1619 Project, which aims to put the history and effects of enslavement—as well as Black Americans’ contributions to democratic reforms—at the center of American history.[9] It examines U.S. history from 1619, the date of the first ship carrying enslaved Africans arrived in colonial Virginia, and explores how the system of slavery shaped the nation’s history.

The article asks if “critical race theory” a way of understanding how American racism has shaped public policy, or a divisive discourse that pits people of color against white people? Liberals and conservatives are in sharp disagreement.

Evelyn Mateos, a USA Today editor headed the project, “Never Been Told: The Lost History of People of Color.”[10] Just days before the one-year anniversary of the death of George Floyd in May, USA Today introduced a yearlong project that seeks to “elevate, through deeply reported investigative and explanatory journalism, the people, places and ideas that are often excluded from history books,” according to a press release.

Racism and history enterprise editor Nichelle Smith, who oversees the project, explained that traditionally, the nation’s history was taught through a White perspective,

Changing that lens, elevating stories that haven’t been elevated, reaching back and getting these stories that have been obscured by time, forgotten in time, erased—intentionally or unintentionally—that is very much our goal.[11]

The debate around CRT has grown more contentious in recent months.

In June 2021, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott signed legislation[12] establishing the “1836 Project,” an advisory committee that he said promotes “patriotic education” and ensures that future generations understand Texas values. The legislation requires the project to promote the state’s “Christian heritage.”[13]

The “1836 Project” is an apparent response to The New York Times’ longform journalism project, “The 1619 Project,” mentioned earlier in this essay.

If Pastor Stephen Feinstein had the chance to turn back time, he said he might not have proposed Resolution 9. The nation’s largest Protestant denomination was unable to meet in person for two years due to pandemic restrictions.[14] The statement adopted by Southern Baptists during their 2019 annual meeting has contributed to a fierce battle over critical race theory. The resolution allowed for CRT to be used as an analytical tool but also stated that it should be subordinate to Scripture.

In sum, much of the current debate appears to spring not from the academic texts, but from recent social movements, political trends and fear among critics that students—especially White students—will be exposed to damaging or racist ideas that might damage their self-esteem.[15]

Parents and Students Weigh In

Exposing students to current events and historical facts can be a healthy way to encourage them to become critical thinkers. We are being presumptuous to believe today’s youth are not intelligent enough to study historical content, synthesize facts and reach important conclusions that will help them become the future opinion leaders of the world. Instead, it is better to teach them age-appropriate content and to balance its truth-filled positive and negative content about people from different cultures. Without a basic knowledge of US history, they will lack some of the same information that other Americans take for granted.

By choosing to avoid some topics in school, we must ask ourselves if future generations will be ill-equipped for college and the “real” world? One thing is certain, children educated in Texas will be forced to play catch up when they are placed in college-level history, political science, media and other courses that will not rewrite history to match the beliefs of today’s Republican legislators. How will they compare with students who have been educated in other states in more traditional academic settings?

A Dallas Morning News article that discusses how the Texas Senate committee advanced a bill aimed at tackling ‘critical race theory,’ includes the following quote from a student:

There’s a lot of discussion about white students’ anguish and learning the truthful racial history of our country. But what is embarrassing and psychologically disturbing to me as a White student who graduated from our schools is thinking you had a great education, and then learning that the adults in charge didn’t trust you with the truth. Our students are capable, and they can be trusted with the truth, and our teachers should be equipped to mediate those critical conversations.

Dr. Kenya Minott, a consultant in Houston who provides anti-racism training, provides insight into how the bill[16] passed by Texas lawmakers might be harmful.[17]

One of the things this legislation and others around the country is causing is keeping the silence [about racism] . . . and that’s harmful for all of us but most particularly students of color.

Counter-arguments focus on how critical theories might be divisive. In the same article, Robin Steenman provides this perspective:

It seeks to divide along racial lines,” she states. “When you start bringing up critical race theory and bringing up skin color, you . . . go back to neo-racism and neo-segregation and it’s a tragedy.[18]

The Franklin, Tennessee, resident runs a local chapter of the national group Moms for Liberty, views critical race theory as an effort to sow strife among Americans and overturn racial progress.

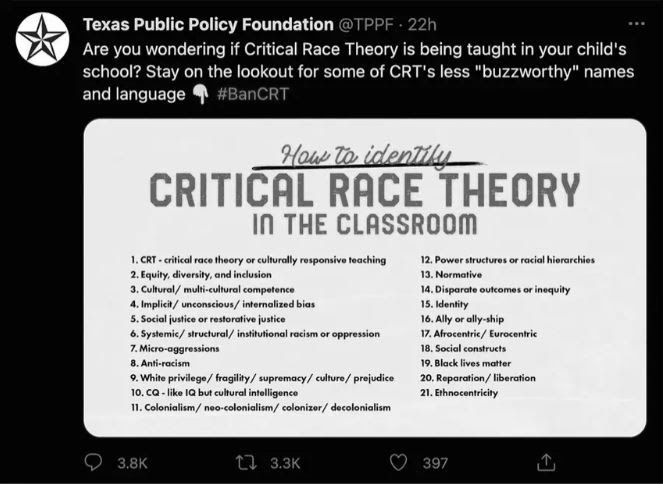

To help parents and teachers identify CRT, a now-deleted tweet by the Texas Public Policy Foundation included the image below, which features a list of buzz words associated with CRT.

<figure id="ndcwjho7ta5" data-node-type="image" data-size="50" data-align="full" data-url="https://assets.pubpub.org/ffe2e9bz/01629114039149.jpeg" data-caption="

” data-alt-text=””>

According to this group, the list of “buzzwords” include: “systemic racism,” “white privilege/supremacy,” “colonialism,” “social justice,” “Black Lives Matter,” “inequity,” “unconscious bias,” and “micro-aggressions,” among others.

Sam Metz (on Twitter as @metzsam) on June 10 shared this tweet, which illustrates an extreme view:

<figure id="naz2lab2n5i" data-node-type="image" data-size="50" data-align="center" data-url="https://assets.pubpub.org/pmq7rt6z/51629114337318.jpeg" data-caption="

Tweet by Sam Metz.

” data-alt-text=””>

The tweet states a group wants Washoe County teachers to wear body cameras to ensure parents that no “critical race theory” is being taught in classrooms.

Janel George, an adjunct professor at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy, where she teaches a course on racial inequality in K-12 public education writes:

The concept of critical race theory, or CRT, has recently been vilified by politicians as a “radical,” “un-American,” and “racially divisive” concept. Several states have even banned schools from teaching critical race theory, with more states debating doing the same. For example, if I taught at a public university in Idaho rather than in Washington, recent legislation would prohibit me from applying a CRT lens in my classroom.

Politicians have encouraged Gov. Greg Abbott to consider strengthening the legislation. A Dallas Morning News article cites Pat Hardy, a Republican member of the State Board of Education and a former history teacher, as urging Abbott to revamp the bill, calling the version that passed “piece-of-junk” legislation.

Aicha Davis, a Dallas-area Democrat who also serves on the State Board of Education and opposed the bill, hypothesized that in sending the issue back to legislators, Abbott intended for House Republicans to strip out some language added by their Democratic counterparts. The group added provisions to require students to learn about diverse communities and leaders, perhaps to make it more palatable.

In an editorial titled, “KING: My thoughts on Critical Race Theory, Texas State Rep. Phil King,” offers this perspective:

Most people believe that CRT is solely about race. It’s not. CRT defines people, actually judges people, by their group affiliation — most often skin color but also sex and economic status — rather than viewing them as individuals created in the image of God. Such division is the very heart of prejudice, discrimination and racism!

He continues:

CRT also falsely accuses (and teaches our children) that the United States is a fundamentally racist nation. In fact, the New York Times 1619 Project specifically states that the purpose of the American Revolution was to protect the institution of slavery. Nothing could be further from the truth![19]

The Future?

The eradication of racial subjugation remains important.

History indicates that after war or disturbance, successful reconciliation may only occur when four things happen: 1) public truth-telling, 2) “redefinition of identities” of antagonists in the conflict, 3) limited justice and 4) a sincere call for moving forward in order to build a new relationship.

If CRT is removed from curricula, its value is diminished. The progress that has been made since the civil rights movement might also disappear. This is the fear most CRT scholars have.

The period of enslavement in American history existed.

Slavery spans many cultures, nationalities, and religions from ancient times to the present day. Likewise, its victims have come from many different ethnicities and religious groups. The social, economic, and legal positions of slaves have differed vastly in different systems of slavery in different times and places.[20]

However, social inequalities still exist. It is important to make space for unpopular opinions and to avoid groupthink. It is also important to extend grace. Just as history should not be rewritten, it cannot be covered up.

We must make an effort to work toward reconciliation, which begins with acknowledgment of previous events. As U.S. citizens, we enjoy privileges that people in many other countries covet.

To whom much is given, much will be required.

— Luke 12:48

My three siblings and I were fortunate to grow up with two teachers as parents. The history lessons our parents taught us served as a buffer from the ones we received at school.

History lessons can be made more palatable when they are balanced by true stories of individuals from all walks of life who have helped others. Children must learn they can achieve their goals despite the missteps of their ancestors.

It’s time for us to come together as one and take responsibility for what we have been blessed with: the United States of America.

Wiping the slate clean is not the answer. If we want future generations of children to learn from the mistakes of their ancestors, we must teach students history as it happened and help them learn to embrace diversity, equity and inclusion.

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

— George Santayana

- Senator Charles Creighton. Relating to the Social Studies Curriculum in Public Schools. Senate Bill 2202, https://capitol.texas.gov/BillLookup/History.aspx?LegSess=87R&Bill=SB2202. Accessed 10 Sept. 2021. ↵

- Rep. Steve Toth, et al. “Relating to the Social Studies Curriculum in Public Schools.” Education, House Bill 3979, 15 June 2021, https://capitol.texas.gov/BillLookup/History.aspx?LegSess=87R&Bill=HB3979. Accessed 10 September 2021. ↵

- Delgado, R. and Stefancic, J. (2012) Critical Race Theory: An Introduction. New York University Press, New York. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Bell, D. (1992). Faces at the bottom of the well: The Permanence of Racism. Basic Books. ↵

- Delgado, R. and Stefancic, J. (2017) Critical Race Theory: An Introduction (3rd Edition). New York University Press, New York. ↵

- Crenshaw, K., Gotanda, N., Peller, G., & Thomas, K. (1995). Critical Race Theory. The Key Writings that formed the Movement. New York, 276-291. ↵

- https://www.edweek.org/by/stephen-sawchuk ↵

- https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/1619-america-slavery.html ↵

- https://eu.usatoday.com/in-depth/news/investigations/2021/05/20/usa-today-project-never-been-told-people-of-color/5147663001/ ↵

- https://www.editorandpublisher.com/stories/untold-stories,199102?newsletter=200191 ↵

- https://www.billtrack50.com/billdetail/1334141 ↵

- https://www.rightwingwatch.org/post/texas-creates-1836-project-to-promote-patriotic-education-and-christian-heritage/ ↵

- https://religionnews.com/2021/06/11/at-least-three-critical-race-theory-statements-proposed-for-southern-baptist-meeting/ ↵

- https://www.edweek.org/leadership/what-is-critical-race-theory-and-why-is-it-under-attack/2021/05 ↵

- https://capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/87R/billtext/pdf/HB03979I.pdf ↵

- https://www.csmonitor.com/Daily/2021/20210604 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- https://www.weatherforddemocrat.com/opinion/columns/king-my-thoughts-on-critical-race-theory/article_3543a2c6-873e-5705-a826-14172ac7bd9f.html ↵

- Klein, Herbert S.; III, Ben Vinson (2007). African Slavery in Latin America and the Caribbean (2nd ed.). New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195189421. ↵