William O. Pate II

A Timeline of Irresponsibility: A Narrative

A timeline recounts nothing, writes scholar Byung-Chul Han in Psychopolitics. “It simply enumerates and adds up events or information.”[1]

Let me begin by adding one narrative — my own — to the preceding “Timeline of Irresponsibility” before more specifically addressing its creation and purpose.

[latex]\dots[/latex]

Prepandemic, when we were still mainly concerned with the Democratic presidential primaries, I was sitting on the porch at Epoch Coffee on North Loop in Austin, as I normally do, when I overheard Wilson, a rotund, gray-haired lawyer who walks with a cane and frequented the shop to play chess and express his Trump support to whomever he was opposing (often silent college-age guys who nodded and focused on the game while Wilson ranted), tell the woman sitting across from him (sans chessboard) that he didn’t want to hear moral reasons for universal health care.[2]

I was incredulous, to say the least. I thought, What else would he like to base it on? Efficiency? I mean, okay, we could do that — it is demonstrably more efficient and effective to have single-payer universal health care: it’s cheaper per capita and provides absolutely everyone with the care they need.[3] But, somehow, I’m rather certain Wilson wouldn’t be interested in those arguments either — people often justify their personal opinions by reference to cost, I’ve often found.[4]

So, I started to think about what might convince him. Say I were to one day actually engage in conversation with him — an event that would undoubtedly devolve into an argument[5] — how could I persuade him (assuming he’s reasonable and, thus, persuadable) that, if we agree we’re all equal (which is sorta a foundation upon which liberal legal[6] doctrine is based), we should all have equal access to the necessary medical treatments. To be clear, I don’t intend to ever actually have this conversation with him.[7]

Then, of course, the novel coronavirus, SARS-Cov-2, which can cause COVID-19, washed onto U.S. shores and unprepared hospitals began to be flooded with the fatally ill, which gave even greater impetus to my search.

I started pondering what quality it is we all — abso-fucking-lutely every single being — have in common that I might base an assumption of fundamental equality on for Wilson.[8]

Because, beyond my lockdown-aided imagined conversation, I was also already in search of an alternative to the existing, widespread neoliberal perspective based on the Cold War-era[9] methamphetamine-[10] and testosterone-induced[11] belief in the fictitious rational autonomous chooser, homo economicus, I want to go farther than just posit human equality. I want to be open to the possibility of an equality recognizing and respecting all beings.[12] The best thing I could come up with is vulnerability.[13]

So, the search became about more than merely human equality to deepening respect for all beings, which, in light of climate change seems equally necessary.

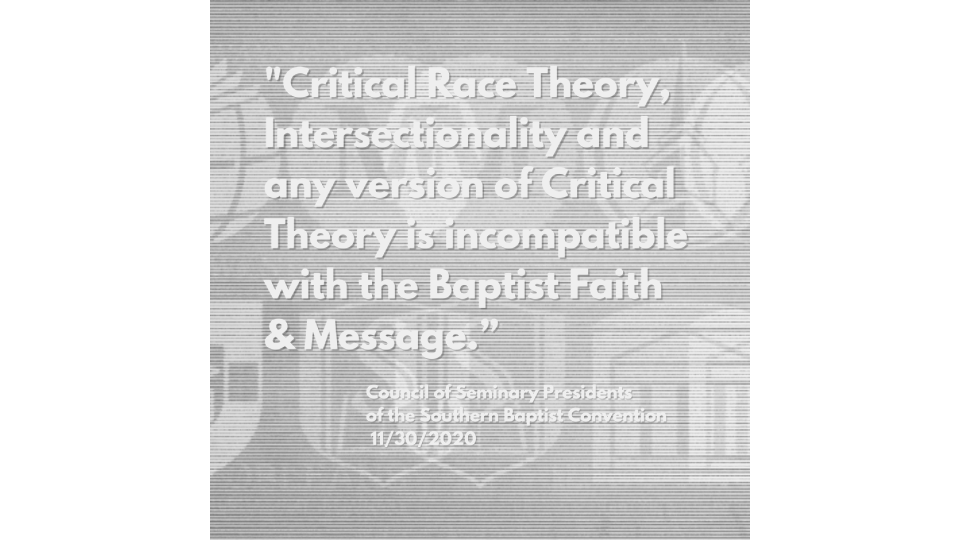

My methodology was necessarily limited — by the pandemic, by my full-time position as a marketer for a legal technology company, my family responsibilities and my perspective as a White male heterosexual living in the Global North (which in no way implies a more “civilized” existence than experienced elsewhere) and relative under-education and economic poverty. Of course, those limitations also provide(d) opportunities otherwise unavailable: as an already-remote worker, the shift to working away from the office was far less disruptive to me or my employer and also afforded me the time between tasks to attend last summer’s Critical Theory Workshop,[14] which was held virtually instead of in Paris in light of pandemic-inspired lockdowns and social distancing protocols.

My other method of investigation, as it has always been, was reading. Maggie Nelson puts it beautifully in The Argonauts when she quotes scholar Luce Irigay describing practicing radical feminist philosophy as “hav[ing] a fling with the philosophers.”[15] And that’s just what I’ve done, though I might replace “philosophers” with “theorists,” specifically critical theorists. But my reading has been wide-ranging.[16] I read because it gives me the opportunity to see what others have said and, more important, what I’m missing. I like to come at problems from both an everyday perspective of what meshes with my experience and the considerations of others on the same or similar topics.

I came to vulnerability after pondering the various obvious commonalities among beings. I started by thinking about birth and the complete dependency of babies on others.[17] I also considered the other end of life: old age. I’ve suggested elsewhere that the dependency needs of older people may once again become center of public attention (similar to the years prior to the establishment of Social Security) as Baby Boomers finally acknowledge their mortality. But dependency — despite being imbued with negative connotations by many on the right[18] — is an effect. What causes us to be dependent is our inherent vulnerability.

On the personal, day-to-day level, it’s difficult to love a domesticated pet without entertaining questions about just how solid the line separating humans and other beings truly is.[19] My reasoning being similar to that Ursula K. Le Guin expressed at a conference resulting in the excellent Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet collection,

Skill in living, awareness of belonging to the world, delight in being part of the world, always tend to involve knowing our kindship as animals with animals. Darwin first gave that knowledge a scientific basis. And now, both poets and scientists are extending the rational aspect of our sense of relationship to creatures without nervous systems and to nonliving beings—our fellowship as creatures with out creatures, things with other things.

. . .

Descartes and the behaviorists willfully saw dogs as machines, without feeling. Is seeing plants as without feeling a similar arrogance?[20]

It is just this slow expansion of recognition/discovery/acknowledgment of the seemingly ever-enlarging sphere of what we consider worth conserving and respecting (and simply affording recognition as “human”) that makes me pause when I start to think I have a grasp on what is what. It’s also part of lived experience.

This becomes even more complicated when one acknowledges that, historically, the non-human has often included many who are clearly human. Elizabeth Grosz describes what I’m talking about well in Becoming Undone:

There is an intangible and elusive line that has divided the animal from the human since ancient Greece, if not long before, by creating a boundary, an oppositional structure, that denies to the animal what it grants to the human as a power or ability: whether it is reason, language, thought, consciousness, or the ability to dress, to bury, to mourn, to invent, to control fire, or one of the many other qualities that has divided man from animal. This division . . . has cast man on the other side of the animals. Philosophy has attributed to man a power that animals lack (and often that women, children, slaves, foreigners, and others also lack: the alignment of the most abjected others with animals is ubiquitous). What makes man human is the power of reason, of speech, of response, of shame, and so on that animals lack. Man must be understood as fundamentally different from and thus as other to the animal; an animal perhaps, but one with at least one added category — a rational animal, an upright animal, an embarrassed animal — that lifts it out of the categories of all other living beings and marks man’s separateness, his distance, his movement beyond the animal. As traditionally conceived, philosophy, from the time of Plato to that of Rene Descartes, affirmed man’s place as a rational animal, a speaking animal, a conscious animal, an animal perhaps in body but a being other and separated from animals through mind. These Greek and Cartesian roots have largely structured the ways in which contemporary philosophy functions through the relegation of the animal to man’s utter other, an other bereft of humanity. (Derrida affirms the continuity that links the Greeks and Descartes to the work of phenomenological and psychoanalytic theory running through the texts of Immanuel Kant, G.W.F. Hegel, Martin Heidegger, Emmanuel Levinas, and Jacques Lacan.) This more or less continuous tradition is sorely challenged and deeply compromised by the eruption of Darwinism in the second half of the nineteenth century. Philosophy has yet to recover from this eruption, has yet to recompose its concepts of man, reason, and consciousness to accommodate the Darwinian explosion that, according to Sigmund Freud, produced one of the three major assaults that science provided as antidote to man’s narcissism. The first, the Copernican revolution, demonstrated that the earth circulates the sun, and the third, the Freudian revolution, demonstrated that consciousness is not master of itself. But the second of these assaults, the Darwinian revolution, demonstrated that man descended from animals and remains still animal, and was perhaps a more profound insult to mankind’s sense of self than the other two. Derrida understands that Darwin’s is perhaps the greatest affront, the one that has been least accommodated in contemporary thought.[21]

Our entanglement with the nonhuman[22] was also brought to mind by Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton’s argument — issued early on in the pandemic — that a species of spiders found only in a certain part of the state should not be protected by the federal Endangered Species Act because it doesn’t engage in interstate commerce. At the time, I called his statement out as an example of David Golumbia’s “fascist language” and what I call disingenuousness to the extreme. The last sentence in his press release cited — of all things — conservation in arguing in favor of the extermination of this species of spider read, “For such localized species, it is the state and county, not the federal government, which can best address conservation.”[23]

Now, a little over a year later, I find that Martha Fineman and others have done much of my work for me.[24] Fineman, a legal theorist working to construct and expound “vulnerability theory,” founded and heads Emory University’s Mission for The Vulnerability and the Human Condition Initiative.[25] She recently defined it as:

Vulnerability theory is a legal/political theory and is shaped by the conventions of those disciplines. It is ultimately centered on the role and function of the state or governing authority as it uses law to construct and maintain the social institutions and relationships that govern everyday life. Viewing these institutions and relationships as central to the reproduction of society, vulnerability theory concedes the inevitability of some form of governing authority that is manifested through law. Vulnerability theory posits that given the innate human condition of vulnerability and dependency not only is there ample justification for the state (or system of governance), but a vigorous and responsive state is essential to individual and collective wellbeing. Beyond the necessity of governance and law, the theory also recognizes the positive potential that governing systems have to respond to and improve the human condition. The theory appreciates and builds upon the potential of the state as a unique mechanism for the construction of a just society, thus distinguishing it from other “progressive” approaches that seem unable to move beyond an oversimplistic notion of an inevitably abusive or punitive state.

. . .

Importantly, our corporeality has significant implications for what we basically require from our social institutions and relationships. Therefore, as a “practical” corrective, vulnerability theory argues that a universal concept — the embodied “vulnerable subject” — should replace the contingent rational man of economics, the reasonable man of law, the contracting man of political theory, as well as the exploited, subordinated, or oppressed man (or woman) of critical theory.[26]

If one sets up a Google Scholar alert for publications including the term “vulnerability,” one begins to notice the concept largely discussed in relation to technology (vulnerabilities to cyberattacks) and climate (vulnerabilities to its change). But a recent paper documenting results of a study projecting changes in vulnerability in Helsinki until 2050 offers a discussion of vulnerability that chimes well with Fineman and others’ approaches:

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change states with high confidence that various factors (e.g. wealth distribution across society, demographic factors, migration, employment, and governance) influence vulnerability and that the drivers interact. Current understanding of drivers, their interlinkages, as well as indirect and cascading effects of socio-economic changes on future vulnerability is limited and needs to be studied further. This presupposes acknowledging system complexity in the assessments, embedding vulnerability in a socio-economic context, and accounting for cross-scale interactions.[27]

The uncertainty and vulnerability laid bare by the pandemic and the disastrous response by many societies — referred to by some as a dress rehearsal for climate change[28] — only add to the urgency of our reconceiving of one another as fallible beings only able to create greatness by actively working, caring, looking out for each other, singularly and plurally. We are too entwined and entangled to continue to believe it’s every individual for itself.