12

Introduction

Virginia Woolf’s, “If Shakespeare had a Sister,” an excerpt from A Room of One’s Own, muses what Shakespeare’s hypothetical sister, Judith, might have been like. In Woolf’s imagination, she was just as creative, just as adventurous, just as gifted a writer as Shakespeare. However, instead of becoming as famous as her brother, poor Judith finds herself laughed at, taken advantage of, pregnant, and dead by suicide. Woolf’s dire prediction is that “It would have been impossible, completely and entirely, for any woman to have written the plays of Shakespeare in the age of Shakespeare” because she would not have had the ability to be creative simply because of the life she would have led (798). Unfortunately, Woolf died before evidence of the creativity of women would be fully uncovered.

The work of prolific female writers of the 1600s and 1700s, within memory of Shakespeare, offer a different perspective. In fact, Fidelis Morgan notes that “during the sixty years from 1920 to 1980…fewer plays by women writers have been performed than were played by the two London companies which held the dramatic monopoly from 1660 to 1720” (xi) and Finberg notes that “The woman playwrights who wrote between the Restoration and the end of the eighteenth century…produced a large body of estimable work” (x). In recent decades, the work of some of these writers, such as Delarivier Manley, Mary Pix, and Catherine Trotter has been rediscovered by modern feminists and put to the forefront of thought as proof that women could, and did, write just a brief time after Shakespeare. Jean Gagen says, “these women—these Mrs. Behns, Mrs. Manleys, Mrs. Pixes and Mrs. Cockburns and the rest—were not only airing their opinions freely but brazenly rivalling men in one of the toughest of profession” (as qtd in McLaren, 80). While these women still faced all of the troubles Woolf notes, they found ways to, not only write, but to show their contemporaries, as well as modern readers, that females may not have been quite so bound as we might suppose.

While it may suit their purposes to paint female authors of the Restoration with a feminist brush, modern scholars who do so fail to appreciate the authors for who they actually were. Milling notes that feminist critics have responded to these playwrights in two ways: “first as the longed-for discovery of female solidarity underpinned by a latent feminism, and second as an act of agency, establishing a feminist bulkhead in masculine discourses of the time” (120). As feminist scholars, we should focus on telling the stories of women, not simply re-writing their lives to suit out own narratives. Setting aside modern proclivities and seeking to get to know Delarivier Manley, Mary Pix, and Catherine Trotter as women does them more service. By getting to know them, we give them personhood, not because they fit our own narrative, but because each author is an individual woman who has value. While these three women are not the only notable writers of the time (we will study The Rover, by Aphra Behn, in the next chapter), this chapter will focus on them.

Delarivier Manley

Her Life

Delarivier Manley was born sometime between 1667 and 1772 on the Isle of Jersey, where her father was the Lieutenant Governor. Her mother died when she was young, and, after her father’s death, she and her sister were delivered to their new guardian, John Manley, who was 23 years Delarivier’s senior and may or may not have already been married. Manley put her in the care of an aunt, “ ‘who would read books of chivalry and romances with her spectacles’ which Delarivier claims ‘infected’ her and made her ‘fancy every stranger that [she] saw…some disguised prince or lover,’” until her death (Morgan, 34).

At this point, Delarivier says, “ ‘My cousin-guardian immediately declar’d himself my lover’” and, after he cared for her during a severe illness, she “ ‘having ever had a gratitude in my nature and a tender sense of the benefits upon my recovery I promis’d to marry him’” at the age of 14 (Morgan, 34). She claims that he kept her a prisoner in an apartment, and, when she despaired of this, he revealed that his wife was still alive, leaving her “ ‘a helpless, useless load of grief and melancholy! With child! Disgrac’d! my own relations either impotent of power or will to relieve me!’” (as qtd in Morgan, 35). Their son was born in 1691.

Just two years later, Manley spent about a year with the Duchess of Cleveland, who thought she brought her luck at cards. Manley also had a short relationship with John Tilly, a jailor, from 1697-1702, when his wife died, and he married again to save his finances.

Her Work

She published her first known work, “To the author of Agnes de Cristo” (Aphra Behn) in 1695 and wrote novels, poetry, letters, and political propaganda, in addition to several plays. Notably, she worked with Jonathan Swift on the Examiner and became its editor in 1711. Her final play, Lucius, was performed at Drury Lane in 1717, and her last novel, The Power of Love in Seven Novels, was published in 1720.

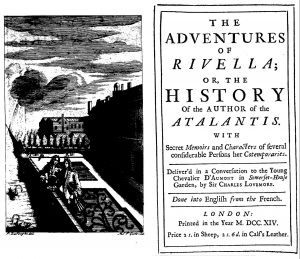

Interestingly, Manley was a master at creating an image of herself for her audience. In fact, as Milling notes, “Manley paints a picture of herself surrounded by admirers, supporters, and men of sense” (127). Though we must read Manley’s autobiography through the lens of fiction, readers get a glimpse into her character via the characters of Rivella in The Adventures of Rivella (1714) and Delia in The New Atalantis. Of Rivella, she writes, “ ‘Her virtues are her own, her vices occasioned by her misfortunes; and yet as I have often heard her say: if she had been a man, she had been without fault’” (as qtd in Morgan, 32).

She believed that she was a talented writer, a woman “ ‘to whom all advantages but mere nature are refused’” (Morgan, 36). She says of herself that, even “in her unfavorable environment she had not forgotten that she was a Cavalier’s daughter: a mistress of the graces of social life, and of brilliant, easy conversation. She had cherished wit as an ideal, and as a heritage of the Restoration. She had read the best authors. She had culture. She knew how to live” (Anderson, 277). Anderson notes that “she made the readers of her autobiography see that the cultivated, passionate, generous, Cavalier gentlewoman had met the strange demands of her difficult life with resolute cleverness and good humor” (276).

Her Legacy

When Manley died in 1724, it was with a “reputation as a witty conversationalist, clever writer, and attentive mentor…” (Hultquist & Mathews, 4). Her tombstone contains an epitaph saying “Here lieth the body of Mrs. Delarivier Manley Daughter of Sir Roger Manley, knight Who, suitable to her Birth and Education, Was acquainted with several parts of knowledge, And with the most polite writers, both in the French and English Tongue. This accomplishment, Together with a Natural Stock of Wit, made her Conversation agreeable to All who knew Her, and her Writings to be Universally Read with Pleasure.’” (as qtd in Morgan, 42).

When Manley’s The Royal Mischief was performed, both Mary Pix and Catherine Trotter wrote tributes. Pix calls her “ ‘the unequalled wonder of the age, Pride of our sex, and glory of the stage…Like Sappho charming, like Aphra, eloquent, Like chaste Orinda, sweetly innocent…’” (as qtd in Morgan, 390). Trotter says, “ ‘Th’ attempt was brave, how happy your success, The men with shame, our sex with pride, confess…You were our champion, and the glory ours. Well you’ve maintained our equal right in fame’” (as qtd in Morgan, 390). Anderson notes she won “Swift’s amused but real respect for her talents”(275) and, upon her illness, Swift wrote, “ ‘…she has very generous principles for one of her sort; and a great deal of good sense and invention’” (as qtd in Morgan, 41). In short, Manley was known for her wit and her ability to write. She was praised by men and women alike during her life and after her death.

Mary Pix

Her Life

Mary Griffith Pix was born in 1666 in Nettlebed, Oxfordshire. Her father, Roger Griffith, was a vicar, though her mother, Lucy Berriman, might have been from a wealthy family. Mary married George Pix in 1684. Their first son, George, lived only a year, but in 1691 they had another son, William.

Mary Griffith Pix was born in 1666 in Nettlebed, Oxfordshire. Her father, Roger Griffith, was a vicar, though her mother, Lucy Berriman, might have been from a wealthy family. Mary married George Pix in 1684. Their first son, George, lived only a year, but in 1691 they had another son, William.

She was friends with Trotter, Manley, Sarah Fyge-Egerton, and Susanna Centlivre (Finberg, xii). Pix was well-liked and known for her good nature and her writing, as well as for her physical appearance.

Her Work

Pix literally burst onto the scene in 1696 with three works—her tragedy, Ibrahim, a comedy, The Spanish Wives, and a novel, The Inhuman Cardinal. Between 1696 and 1706 she produced six comedies and seven tragedies. Mentored by William Congreve, Pix’ plays “became a staple” at Betterton’s company at Lincoln’s Inn Field (Finberg, xii).

Her first play, Ibrahim, was revived in 1702, 1704, and 1715, highlighting her skill at writing and the play’s popularity (Morgan, 45). According to Morgan, Pix showed her play to Queen Mary, and “ ‘Her Royal Highness showed such a benign condescension as not only to pardon [her] ambitious daring, but also encouraging [her] pen’” (47). It was said of her that “ ‘in this poetic age, when all sexes and degrees venture on the sock and buskins, she has boldly given us an essay of her talent in both, and not without success, though with little profit to herself’” (as qtd in Morgan, 50).

Modern readers can get a few clues about how Pix perceived herself from the many prefaces, prologues, and dedications to her work. In the preface to Ibrahim, for example, Pix refers to her education, saying that the inspiration for the play was a book she had read: “ ‘I read some years ago at a Relation’s House in the Country, Sir Paul Ricaut’s Continuation of the Turkish History; I was pleas’d with the story and ventur’d to write upon it…’” (qtd in Oney, 39). In her dedication to The Spanish Wives, Pix mentions a lifelong affinity for writing, saying, “ ‘You have known me since my Childhood, and my Inclination to Poetry…’” (qtd in Oney, 39). In both instances, readers get a glimpse of an educated woman who has always been interested in literature.

Like Manley, Pix commented on the reception that she received as a woman. She said that “ ‘I am often told, and always pleased when I hear it, that the work’s not mine’” (as qtd in Morgan, 45). In other words, her writing was so good that it was supposed that she, as a woman could not have written it. Rather than be angry with it, she displays her good nature and says she is pleased.

Nonetheless, Pix is confident enough to stand up for herself when she is wronged, able to take care of herself. When Powell plagiarized her play, she opened The Deceiver Deceived with these words: “ ‘…I look upon those that endeavour’d to discountenance this Play as Enemys to me…he has Printed so great a falsehood, it deserves no Answer’” (qtd in Oney, 103).

Her Legacy

Finberg notes that Mary Pix “was a well-respected, and almost universally well liked, member of London’s literary community” (xi). Tom Brown calls her “the jolly poetess” (qtd in Oney, 106). Pix was apparently well-educated and well-liked among her peers, and her plays were very popular. Finberg notes that “her words display evidence of significant education in languages and literature” (xiii). In addition, Oney notes that “Pix was well aware of the proper medium for her work: the live theater. In fact, Pix is the playwright who repeatedly arrives at the most theatrical, stage worthy means to tell her story” and “possesses the surest sense of the possibilities of the stage” (82, 83).

Catherine Trotter

Her Life

Catherine Trotter was born on August 16, 1679, to Captain David Trotter and Sarah Ballenden. Captain Trotter died from the plague while hoping to secure his fortune in 1684, leaving his wife and two daughters with very little.

Catherine Trotter was born on August 16, 1679, to Captain David Trotter and Sarah Ballenden. Captain Trotter died from the plague while hoping to secure his fortune in 1684, leaving his wife and two daughters with very little.

When she married Mr. Cockburn in 1708 in Suffolk, Catherine gave up writing altogether to tend to her household and raise their three children: “ ‘Being married in 1708, I bid adieu to the muses, and so wholly gave myself up to the cares of a family, and the education of my children, that I scarce knew whether there was any such thing as books, plays or poems stirring in Great Britain’” (Morgan, 29). It wasn’t until the 1730s that she began writing publicly again, and she died in 1749 at the age of 70.

Her Work

Catherine began writing at a very young age, composing verses to the well-known Bevil Higgins at the age of 14 after his bout with small pox, and publishing her first play in 1693, which put Aphra Behn’s novel Agnes de Castro on the stage. She wrote several plays, but only one comedy, Love at a Loss, which was performed in 1700 at Drury Lane.

Not only did Catherine write creatively, but she also used writing to express her thoughts, writing praise for authors, such as Congreve, as well as thoughtful pieces defending the work of John Locke.

Trotter’s own writing about herself only adds to our understanding of her personality, illustrating both her intelligence and her character. She defends her intelligence and ability saying, “ ‘Women are as capable of penetrating into the grounds of things and reasoning justly as men are who certainly have no advantage of us but in their opportunities of knowledge’” (as qtd in Morgan, 27). Not only was she sure of her own intelligence and ability, but she determined to use those abilities for good, which makes sense since she was determined to marry a pastor.

Trotter said of herself in the preface to The Revolution of Sweden in 1706 that “ ‘I…could never allow myself to think of any subject that cou’d not serve either to incite some useful virtue, or check some dangerous passion. With this design I thought writing for the stage a work not unworthy…’” (as qtd in Morgan, 28). This echoes her earlier thoughts in The Nine Muses about the reason for writing: “ ‘Let none presume the hallow’d way to tread, By other than the noblest motives led. If for a sordid gain, or glitt’ring fame, To please without instructing be your aim, To lower means your groveling thoughts confine, Unworthy of an art that’s all divine’” (as qtd in Morgan, 26). Birch quotes her as saying that she hopes that “ ‘the sincere love, which she had for truth, and charity for those, who differed from her, would atone for the errors of her understanding’” (xxiv). Catherine, in her own words, was concerned with using her writing, and thus her intelligence, for good.

Her Legacy

Catherine was said to be “admirable for two things rarely found together, wit and beauty” (as quoted in Morgan, 31). Her biographer, Thomas Birch, says that, “with a genius equal to the most eminent of them, [she] had the superior advantage of cultivating it in the only effectual method of improvement, the study of a real philosophy, and a theology truly worthy of human nature, and its all-perfect author” (ii). She “taught herself to write, and learned French without the aid of a teacher, although she was assisted in Latin and logic” (Morgan, 214; Birch iv-v).

Her work was praised by Charles Gildon, William Congreve, and George Farquhar. John Locke wrote her saying, “ ‘…as the rest of the world take notice of the strength and clearness of your reasoning, so I cannot but be extremely sensible, that it was employed in my defence. You have herein not only vanquished my adversary, but reduced me also absolutely under your power…’” (as qtd in Morgan 27). In Lives and Characters of the English Dramatic Poets, written in 1699, Trotter’s entry reads in part, “ ‘ There is the chastity of her person and the tenderness of her mind in both…if there be not the sublime, ‘tis because there was no room for it, not because she had not fire and genius enough to write it’” (as qtd in Morgan, 31).

Her biographer, Birch, remarks on her “ ‘extremely amiable character,’” “ ‘innocent , useful, and agreeable’” conversation, and “ ‘remarkable modesty and diffidence of herself’” (as qtd in Morgan, 31). Manley also praises Trotter, “Fired by thy bold example, I would try To turn our Sexes weaker Destiny” (as qtd in Miller, 120). Catherine’s friend, Lady Piers writes in her poem, “To the excellent Mrs. Catharine Trotter,” “ ‘By thy judicious rules the hero learns To vanquish fate, and wield his conqu’ring arms; The bashful virgin to defend her heart; The prudent wife to scorn dishonest art; The friend sincerity; temp’rance the youth’” (as qtd in Birch, xiv). In other words, Catherine was known by her contemporaries to be both intelligent and of good character.

Concluding Thoughts

Rather than try to make Manley, Pix and Trotter fit into a modern feminist mold, the best way to honor these playwrights is to get to know them as women writers who engaged with their culture in their own way. Manley, Pix, and Trotter show modern audiences that women were not silent, as previously supposed. Their successes, and even their failures, should be celebrated because they are proof that women, did, indeed write. They did have space. As we continue to honor their work by reading it and studying it today, we breathe life into their work and allow their legacy to live on.

Works Cited

Anderson, Paul Bunyan. “Mistress Delarivere Manley’s Biography.” Modern Philology, Vol. 33, No. 3 (Feb. 1936), pp. 261-278. The University of Chicago Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/434067. Accessed 4/23/2019.

Birch, Thomas. The Works of Mrs. Catharine Cockburn: Theological, Moral, Dramatic, and Poetical. J. and P. Knapton, 1751. Republished by University Microfilms International, 1978.

Ballaster, Ros. “Delarivier Manley (c. 1663-1724).” Chawton House Library, 2012.

https://chawtonhouse.org/wp-content/uploades/2012/06/Delariver-Manley.pdf.

Accessed 23 April 2019.

Finberg, Melinda C., et al. Eighteenth-Century Women Dramatists. Oxford University Press, 2008.

Finke, Laurie A. “The Satire of Women Writers in The Female Wits.” Restoration: Studies in English Literary Culture, 1660-1700, vol. 8, no. 2, 1984, pp. 64–71. Mlf, EBSCOhost, libproxy.nau.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mlf&AN=1984082373&site=ehost-live&scope=site. Accessed 11 Mar. 2019.

Hook, Lucyle, ed. & introd. The Female Wits (Anonymous) (1704). Clark Memorial Library, UCLC, Nov. 1967. Mlf, libproxy.nau.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mlf&AN=1967106372&site=ehost-live&scope=site. Accessed 11 Mar. 2019.

Hultquist, Aleksondra, and Elizabeth J. Mathews. New Perspectives on Delarivier Manley and Eighteenth Century Literature: Power, Sex, and Text. Routledge, 2017.

McLaren, Juliet. “Presumptuous Poetess, Pen-Feathered Muse.” Gender at Work: Four Women Writers of the Eighteenth Century, edited by Ann Messenger. Wayne State Univ. Press, 1990.

Milling, Jane. “The Female Wits: Women Writers at Work.” Theatre and Culture in Early Modern England, 1650-1737: From Leviathon to Licensing Act, edited by Dr. Catie Gill. Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2010.

Morgan, Fidelis. The Female Wits (Anonymous) 1697. The Female Wits: Women Playwrights on the London Stage 1660-1720. Virago Press, 1992.

Oney, Jay Edward. Women Playwrights During the Struggle for Control of the London Theatre.

1965-1710. 1996. Ohio State University, PhD dissertation.

Ozment, Kate. “’She writes like a Woman’: Paratextual Marketing in Delarivier Manley’s Early

Career.” Authorship 5.1 (2016). DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21825/aj.v5i1.2354.

Woolf, Virginia. “If Shakespeare Had a Sister.” Exploring Literature. Frank Madden, ed.

Longman, 2012. 798-99.

Content of this chapter written by Dr. Karen Palmer and licensed under CC BY NC.

Media Attributions

- 1385px-1714_Manley_Adventures_of_Rivella

- The_lively_portraiture_of_Mrs._Mary_Griffith_(4670797)_(cropped)

- Catherine_Cockburn