14

Chapter Contents

Introduction

For the purposes of this text, “modern literature” refers to a period of about 200 years (around 1800 to the modern day). Of course, our world has seen many changes in this time, including two World Wars!, and the literature of each period reflects the changing attitudes and ideas in the world.

In this chapter, we will briefly cover the evolution of literature beginning with Romanticism and Realism in the “long 19th century,” then moving into Modernism, Post-Colonialism, and Contemporary Literature in the 20th and 21st centuries.

But, before you begin, I invite you to read this article that reminds us that, regardless of what was happening in the world, for many writers, their own lives, families, and experiences had the greatest influence on their work:

Marshall, Paule. “Poets in the Kitchen.” The New York Times, Jan. 9, 1983.

Marshall, the author of Brown Girl, Brownstones, The Chosen Place, the Timeless People, and Praisesong for the Widow, talks about the influence of women in her life on her writing. In her final paragraph, she says,

Romanticism

When you think of Romanticism, you might think of Jane Austen and the Bronte sisters. These are definitely examples of Romantic era authors, but there is more to being a Romantic author than writing romance.

When you think of Romanticism, you might think of Jane Austen and the Bronte sisters. These are definitely examples of Romantic era authors, but there is more to being a Romantic author than writing romance.

Although the publication of Wordsworth’s Lyrical Ballads in 1798 is often heralded as the formal start of Romanticism, the roots of the movement began earlier. The Enlightenment, or Age of Reason, had embraced the power of rational thought and the scientific method to advance society in an orderly fashion. Romanticism, however, heralded a more individual approach, often guided by strong emotions and some type of spiritual insight.

According to Romantics, deeper understanding of the world was achieved through intuition and emotional connections, rather than reason. In literature, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was one of the early proponents of the Storm and Stress (Sturm und Drang ) period, which rejected the Enlightenment’s focus on reason in favor of strong emotions and the value of the individual. Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774) is a classic Storm and Stress novel, with a protagonist driven by his extreme emotions.

In politics, the revolutions of the time were driven by certain Enlightenment concepts that would be important to later Romanticism: in particular, the idea of natural rights, which was discussed by politicians, philosophers, and writers alike. John Locke asserted that human beings have the right to life, liberty, and property, and Francis Hutcheson posited the difference between alienable and unalienable rights.

Thomas Jefferson used these ideas more or less directly in his writings. Rather than owing loyalty to a monarch, the Declaration of Independence (1776) asserts that human beings have rights from God and the laws of nature that cannot be taken away by an earthly ruler. The French Revolution and the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte (a fan of The Sorrows of Young Werther who claimed to have read the novel many times) also challenged established authority.

Romanticism, as practiced by Wordsworth, is a natural outgrowth of those revolutionary ways of thinking. If human rights are derived from “the laws of nature and of nature’s God” (Jefferson), then it makes sense that Wordsworth sees God’s presence in nature. In his poetry, nature represents truth, purity, and innocence, so the poet praises children and women as closer to God, because he sees them as closer to innocence.

Wordsworth also highlights how the “other” revolution—namely, the industrial revolution—had begun to affect society in increasingly negative ways. Wordsworth contrasts the pollution of urban areas with pristine nature, characterizing modern urban life as a loss of connection to spiritual values.

Wordsworth, however, is only one of many voices in Romanticism. If Wordsworth saw women as childlike in their innocence, other writers disputed whether that was, in fact, accurate (or desirable). Women responded to the debate about the rights of man by discussing the rights of women, leading to works such as The Declaration of the Rights of Women (1791), by Olympe de Gouges, and A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792), by Mary Wollstonecraft.

If nature could be a source for inspired reflection in Wordsworth, it could also be dangerous. Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan,” which touches on the Romantic idea of poet as genius at the end, notes the thin line between genius and madness. Exceptional individuals as protagonists are the norm in Romanticism, in part from the (early) admiration for Napoleon Bonaparte. The admiration for Bonaparte, however, began to fade among many Romantic poets as he became a part of the monarchy and a more traditional figure of authority.

One type of exceptional individual, the Romantic hero, has either rejected society or been rejected, and therefore is no longer constrained by society’s rules (with the reminder that a Romantic hero is not necessarily romantic, but rather a product of Romanticism). Romantic heroes tend to be self-centered and arrogant, but are capable of compassion and even self-sacrifice, in some cases.

A Byronic hero is a subset of Romantic hero, named for the poet Byron, who was described as “mad, bad, and dangerous to know.” The distinction between the two types can get murky, since the Byronic hero is in some ways simply a bit more dangerous and alienated than the Romantic hero (in fact, characters such as Heathcliff in Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights and Faust in Goethe’s Faust have been called both by various literary scholars). Byronic heroes are more likely to have some guilty secret in the past, or some unnamed crime that is never revealed, which drives the characters’ actions, and they are more likely to end tragically.

There were critiques of Romanticism even during the movement. In Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, she questions both Enlightenment views of science and Romanticism’s view of the hero. The first narrator, Robert Walton, fails miserably to advance scientific exploration in the Arctic, while risking the lives of others. Similarly, Victor Frankenstein’s self-absorbed behavior slowly destroys everyone around him. Victor’s passivity and silence become more and more criminal as the novel progresses. Mary Shelley began the novel while she and her future husband, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, were spending time with Byron, which makes her critical analysis even more intriguing.

Please watch this video from School of Life on the History of Romanticism:

“Romanticism” adapted from Compact Anthology of World Literature II, Volume 5, licensed under CC-BY-SA.

Realism

The dates for Realism as a movement vary, from as early as 1820 to as late as 1920. Although Realism is, in many ways, a rejection of Romanticism, it does address some of the same concerns about the industrial revolution that Wordsworth had expressed earlier. The passage of years increased the number of authors who noted the failures of industrialization, especially where pollution and quality of life were concerned. The British period of Victorianism (1837-1901) saw a gradual shifting from Romanticism to Realism. Poets such as Tennyson and Robert Browning are more properly transitional poets: products of Romanticism, but who express themselves in more realistic terms.

The dates for Realism as a movement vary, from as early as 1820 to as late as 1920. Although Realism is, in many ways, a rejection of Romanticism, it does address some of the same concerns about the industrial revolution that Wordsworth had expressed earlier. The passage of years increased the number of authors who noted the failures of industrialization, especially where pollution and quality of life were concerned. The British period of Victorianism (1837-1901) saw a gradual shifting from Romanticism to Realism. Poets such as Tennyson and Robert Browning are more properly transitional poets: products of Romanticism, but who express themselves in more realistic terms.

It is important to remember not only that literary movements are not set in stone, but also that they are not always identified the same way by their own time period. When Charles Baudelaire wrote his seminal work, The Flowers of Evil (1857), he was praised as a poet of Romanticism by Gustave Flaubert, even though most modern scholars locate Baudelaire in Realism, and later poets of Modernism cite him as an early example of their own movement.

Romanticism was slowly but surely replaced with an attempt to see the world as it is. As later generations would note, it is difficult to represent reality in its entirety in one poem, play, short story, or novel. Early Realists tended to include more portrayals of middle class and/or lower class characters, who previously were not the main subjects of literature. In Europe, writers such as Ibsen wrote about the middle class specifically, using ordinary occurrences (at least, ordinary for the middle class experience) as the stuff of drama. Authors such as Henry James occasionally were criticized for novels in which very little seems to happen, since ordinary events are rarely as dramatic as the situations regularly found in Romanticism. In some cases, the attempt to be more realistic led to many works that focused on the negative aspects of humans, leaving out the positive aspects to avoid Romantic overtones.

Instead of Romanticism’s belief in the power of emotion and intuition to achieve insight, Realism addressed more concrete issues, usually with direct and straightforward language. In American Realism, Mark Twain’s use of dialect falls into this category. Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884) is realistic in its use of common, everyday speech, which includes dialect and slang. The novel also offers a realistic portrayal of the complicated friendship that slowly develops between Huck, a poor white boy, and Jim, a runaway slave.

Another way that Realism distinguished itself from the previous movement was in its examination of human psychology. Robert Browning looked at the psychology of narcissists, murderers, and psychopaths in many of his dramatic monologues. Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s novels take place as much in the minds of the characters as they do in the interactions among characters. In Notes from Underground (1864), Dostoyevsky uses Realism to explore the allure (and dangers) of Romanticism, including its continuing hold on audiences. Dostoyevsky’s “Underground Man” attempts to explain not only why he does what he does, but claims that the reader is no different—a tactic used by Baudelaire in his poem “To The Reader” at the beginning of The Flowers of Evil.

As a general guideline, Realism tended to point out society’s problems (and the problems with the Romantic view), but offered observations, rather than suggested changes.

Naturalism, a subset of Realism often treated as a separate movement, was regularly motivated by a desire to improve the world. Naturalism concerned itself with the poorest members of society in particular, and social change was the goal. Naturalism was criticized for being even more focused on the negative aspects of life than regular Realism. Emile Zola’s novel Germinal (1885) is perhaps the most famous example of Naturalism. In it, Zola depicts the lead-up to and aftermath of a coal miners’ strike with a stark realism that shocked readers. His unsentimental portrayal (in almost journalistic fashion) of events angered both conservatives (reluctant to admit the brutal working and living conditions of the poor) and socialists (unhappy that the workers were not Romantic heroes).

Eventually, Modernism began in literature as Realism and Naturalism were ending, overlapping for a brief period of time. Perhaps not surprisingly, Modernism would claim to be more real than Realism—or, as the artist Georgia O’Keeffe said, “Nothing is less real than realism” (Haber), preferring abstract art as a way to arrive at a more complete image of (one type of) truth.

Here’s a short video by Marc Schuster on Realism in literature:

“Realism” adapted from Compact Anthology of World Literature II, Volume 5, licensed under CC-BY-SA.

Modernism 1900-1945

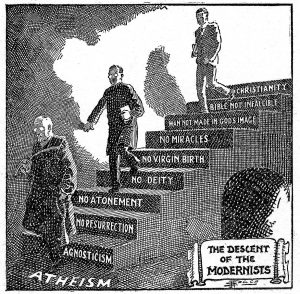

The philosophical movement in art and literature that we call “Modernism” was characterized by the artist’s response to two powerful forces: the effects of industrialization and the aftermath of wars, particularly the Russian Revolution and World War I. Modernist writers and artists rejected the certainties of Victorian culture, particularly conventional religious faith and respect for authority. Perhaps the most fundamental underlying tenet of Modernism is that traditional ways of thinking about art, music, literature, government, religion, sex, civil rights, architecture, fashion, and other aspects of daily life should be questioned and re-invented.

“The Descent of the Modernists”, by E. J. Pace, first appearing in the book Seven Questions in Dispute by William Jennings Bryan, 1924. License: Public Domain.

We can trace the roots of Modernism to writers, artists, poets and philosophers of the late 19th century. For example, Sigmund Freud’s theories on the importance of the unconscious, published between 1899 and 1930, certainly influenced writers like Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, and T.S. Eliot to explore the interior lives of their protagonists.

Thus, the use of internal monologues and stream-of-consciousness techniques became an important characteristic of Modernist poetry and fiction. Frederic Nietzsche’s theory of “the will to power,” his argument that the primary driving force in humans is toward achievement and success, also influenced novelists and short story writers like Dorothy Richardson and Katherine Mansfield.

Critics generally point to such writers and playwrights as August Strindberg, Anton Chekhov, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, W.B. Yeats, Henry James, and Charles Baudelaire as exhibiting experimental techniques and themes that would come to be associated with Modernism. The Impressionist, Expressionist and Cubist movements in visual arts, encompassing artists like Edouard Manet, Claude Monet, Vassily Kandinsky, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso also typify the spirit of resistance and a desire to create art that spoke to the contemporary condition of men and women in a rapidly changing world.

Blast magazine (1914), an avant garde publication that lasted only two issues, published a manifesto that reflects some of the impulses and contradictions of Modernism. While the manifesto was signed by a number of artists and writers who identified as members of the Vorticist movement, its chief architect was Wyndham Lewis, an English painter and critic. The Vorticists, like the Futurists in Italy, attacked traditional art and literature and celebrated the power and energy of technology. Vorticists celebrated England as the vortex of youthful energy and power. They rejected the bourgeois values and stifling convention of Victorianism and advocated for violent change. Vorticists considered themselves to be “Primitive Mercenaries in the Modern World” and arguing that “The artist of the modern movement is a savage . . . this enormous, jangling, journalistic, fairy desert of modern life serves him as Nature did more technically primitive man.”

Another influential Modernist publication is Virginia Woolf’s 1921 essay “Modern Fiction,” in which Woolf exhorts writers to reject the trivialities of the realistic approach in favor of free expression and form that will reflect the complexity of modern life: “Life is not a series of gig lamps symmetrically arranged; life is a luminous halo, a semi-transparent envelope surrounding us from the beginning of consciousness to the end.” Meanwhile, iconoclastic American poet Ezra Pound exhorted fellow poets and writers to “make it new.” Woolf’s and Pound’s exhortations to re-imagine traditional literary genres reflects the spirit of Modernism and influenced many of their fellow writers and poets.

In the United States, this period also ushered in the Harlem Renaissance, a “golden age” for African American literature, art, and music that is generally dated from 1918 to the mid-1930s and was centered in the Harlem district in New York City. Like the original Renaissance, this movement saw an explosion of creative energy that resulted in extraordinary works that both documented the African American experience and experimented with style and genre.

Writers, poets, philosophers, musicians, and visual artists like Langston Hughes, W.E.B. DuBois, Zora Neal Hurston, Claude McKay, Louis Armstrong, and Duke Ellington produced works grounded in the “New Negro Movement,” asserting that artistic and intellectual achievement could challenge stereotypes and racism. The pinnacle of the movement is generally considered to be the period between 1924 and 1929, the beginning of the Great Depression.

Modernist writers and poets responded to war, financial collapse, and social change by experimenting with traditional forms and conventions. Given the dramatic events they witnessed, these writers challenged the traditional Enlightenment view of human beings as primarily rational in texts that explored the chaotic workings of the human unconscious. Poets and writers alike made use of images, symbols, and allusions to mythology and Jungian archetypes. In the theatre as well, playwrights like Luigi Pirandello challenged the comfortable assumptions of audiences by breaking down the “fourth wall” of the play and encouraging members of the audience to think more critically about the action onstage.

Here’s a short video overview of Modernism in Literature by Flippin’ English:

“Modernism” from Compact Anthology of World Literature II, Volume 6, licensed under CC-BY-SA.

Post-Colonialism

The post-World War II era and postcolonialism largely overlap. World War II (1939-1945) created a particular zeitgeist (or a defining spirit of the time), which consequently shaped the literary works published immediately after the war. Polish catholic writer Tadeusz Borowski’s short story “This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentlemen” (1946) is an example of post-World War II literature, which reflects the author’s experience of having observed, and having been complicit with, the brutal workings of the Holocaust. The first-person narrator’s sense of nausea and being stuck in the short story echoes the major sentiments of post-World War II literature.

The post-World War II era and postcolonialism largely overlap. World War II (1939-1945) created a particular zeitgeist (or a defining spirit of the time), which consequently shaped the literary works published immediately after the war. Polish catholic writer Tadeusz Borowski’s short story “This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentlemen” (1946) is an example of post-World War II literature, which reflects the author’s experience of having observed, and having been complicit with, the brutal workings of the Holocaust. The first-person narrator’s sense of nausea and being stuck in the short story echoes the major sentiments of post-World War II literature.

The post-World War II era also coincides with the post-independence period. After World War II and during the second half of the twentieth century, many formerly colonized places began to gain independence. In this historical milieu, postcolonialism as an academic field developed in the late 1970s—markedly with the 1978 publication of Edward Said’s seminal book Orientalism, in which Said examines how euro-centric cultural representations of the “Orient” reveal the West’s biases, stereotypes, and/or fantasies about the “Orient.”

Postcolonialism reached further sophistication by notable postcolonial scholars such as Homi Bhabha and Gayatri Spivak. Unlike the term “postindependence,” which focuses on the temporal and periodizing meaning of “post” as “after,” the term “postcolonial” has now become more of a theoretical concept, concerning the study of the varied processes and effects of colonialism from the perspectives of the (formerly) colonized; in this sense, postcolonialism could apply to cultures before, during, and after the workings of colonialism. Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (1958) is one of the best-known works of postcolonial literature. Beyond the scope of the works produced from the newly decolonized countries of Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean, postcolonialism—as it concerns colonial histories and the voices of the oppressed people—is also associated with Indigenous peoples’ experiences around the globe. Some of Joy Harjo’s poems concern colonial history and Native Americans’ experiences.

The post-independence era and postcolonialism come with other related concepts and new global realties, such as cultural hybridity, immigration, diaspora, and globalization. Postcolonial literature is also often noted for demonstrating cultural hybridity in its style and theme and/or engaging with the dilemma of conflicting cultures.

“Post Colonialism” from Compact Anthology of World Literature II, Volume 6, licensed under CC-BY-SA.

Contemporary Literature (1955-Present)

After World War II ended, the international community spent many years rebuilding and coping with the aftermath of the destruction of cities, towns, roads, national economies, and social structures. One response to the upheaval caused by the War was for ethnic communities or colonized nations to seek political or cultural autonomy. In addition, the mid- to late-twentieth century period encompassed significant cultural and political developments worldwide:

- The formation of the Soviet bloc nations and the partitioning of Germany set the stage for the political tensions that would culminate in the Cold War between the United States and Soviet Russia that lasted from the 1950s through the 1980s and established a constant threat of nuclear war

- The creation of the state of Israel in 1948 led to a continuing series of Arab-Israeli conflicts

- The partitioning of Korea and Viet Nam led to civil wars in those nations that came to involve the United States and European nations in the effort to stop the spread of Communism

- China, under Mao Tse Tung, and then continuing under the control of the Communist party, began to emerge as a world power

- Japan recovered from the devastating effects of the nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and became an important trade partner for U.S. and European countries

- The social and political upheaval of the 1960s and 1970s resulted in the emergence of the recreational drug culture, the Civil Rights movement in the United States, the international Feminist movement, and the rise of the revolutionary political left.

In response to these galvanic changes, literature of the mid- to late-twentieth century is sometimes characterized by critics as “postmodern,” a term that loosely reflects a shifting set of themes and strategies. Unlike Modernists, who tended to welcome classification and identification with a defined movement, postmodernists resist manifestos, instead considering themselves more as subversive individualists. However, it is possible to suggest some broad tendencies that characterize literature of the mid-twentieth century to the early twenty-first century.

Characteristics of Contemporary Literature

First, these poets, playwrights, and fiction writers, while resisting identification as modernists, share the same impulse to experiment with subjectivity and the inner life. Thus, fiction during this period continues to be marked by the investigation of interiority through the use of internal monologues, free indirect discourse, and stream of consciousness techniques.

As a response to the Cold War, another characteristic of the literature of the period is a tendency to present dystopian themes. From the late-1950s through the mid-1980s, the world often seemed poised on the brink of nuclear war, and the themes of works of the period reflect these anxieties.

Nonlinear narrative structures are also widely associated with postmodern texts. These texts use fragmented organizational patterns, flashbacks, or even alternate histories to disrupt and subvert the reader’s expectations and assumptions. The use of alternate history or anachronisms have been effectively employed recently by Margaret Atwood in The Handmaid’s Tale (1985).

Magical realism, the juxtaposition of a generally realistic plot with interventions of the supernatural, fantastic, folkloric, or mythical, is another technique that has emerged during this period, most often associated with the works of Juan Luis Borges and Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

With increasingly urgent discussions of issues surrounding national or ethnic identity, gender bias, and sexuality, writers, poets and playwrights have begun to explore themes of personal identity.

“Contemporary Literature” from Compact Anthology of World Literature II, Volume 5, licensed under CC-BY-SA.

Feminist Literature

Free women: Literature and consciousness-raising

Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook (1960), heralded the new era. We meet Anna Wulf, a writer and single mother with writer’s block, exploring her disillusionment with men, communism, and violent resistance. She decides to keep four notebooks, one for each part of her life – black for her experiences in Africa, red for politics, yellow for a fictionalised version of herself, and blue for a diary, weaving around a novel-within-the-novel, titled ‘Free Women’. Lessing said this complex structure was to show the fragmentation of a woman’s mind, and how, through writing, she might put her identity back together.

Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook (1960), heralded the new era. We meet Anna Wulf, a writer and single mother with writer’s block, exploring her disillusionment with men, communism, and violent resistance. She decides to keep four notebooks, one for each part of her life – black for her experiences in Africa, red for politics, yellow for a fictionalised version of herself, and blue for a diary, weaving around a novel-within-the-novel, titled ‘Free Women’. Lessing said this complex structure was to show the fragmentation of a woman’s mind, and how, through writing, she might put her identity back together.

Feminist film director Michele Ryan encountered The Golden Notebook at a point of confusion in the early 1970s:

I remember sitting on a bus and … feeling, yes, this is absolutely where I’m at, and I’ve got to, kind of, hold my centre a bit better. … I suppose because I did have politics, I did have the Women’s Movement, I did have the theatre at the time, I had things that belonged to me, and I wasn’t going to let go of those, in order to fit into a man’s life.

The Golden Notebook was a breakthrough example of a wave of ‘consciousness-raising’ writing and film.[1] Margaret Drabble, Nell Dunn, Shelagh Delaney, Eva Figes, Ann Oakley, Alison Fell, Sara Maitland, Michelene Wandor, Fay Weldon, Anne Devlin, Michele Roberts, and poets Sylvia Plath, Grace Nichols, Liz Lochhead, Denise Riley and many others captured the distinct flavors of women’s struggles in Britain: class manners and working class wit; laborious arguments in and with the Left; boring food; drab weather; the deceptive dazzle of London and the disappointments of a sexist counterculture. Buchi Emechta’s Second Class Citizen (1974) engages with these themes while exploring the particular disappointments of the women who came to the UK from former colonies after the war. Her Nigerian protagonist Adah is determined to succeed as a writer but a cruel husband and demanding children combine with the indignities of racism in dreamed-for England. Written in the first person, with rage, humour and ambition, these novels rewrite the bildungsroman to show the new journey women must take, a journey which no longer ends with Mr Right.[2]

Utopias, dystopias, gothic fantasies and the gender of other worlds

Women writers have often used a style of domestic realism – reflecting the family homes in which they have laboured and nurtured. But in the 1970s and 80s they also took up science fiction, fantasy or historical fiction to explore gender relations on an epic scale. In Britain, Zoe Fairbairns’s Benefits, published six years before Atwood’s better known The Handmaid’s Tale, is a feminist literary gem. Set in 1976, this dystopia has a woman prime minister use welfare benefits to force women back into the nuclear family, uncannily anticipating Thatcher’s reign. Based in part on Fairbairns’ experiences volunteering for an abortion charity – ‘I listened to women who felt unable, because of poverty, to continue their pregnancies’ – it is also dryly funny about feminists’ own behavior: endless meetings, lesbian shenanigans and leadership panics.

Angela Carter, an even more experimental writer, was also satirical about women as well as men. The Bloody Chamber, published in 1979, demythologised innocent Red Riding Hood with what she claimed was the ‘violently sexual’ latent content of the traditional fairy tale form. Carter developed such thoughts controversially in The Sadeian Woman, published the same year, in which she returned to the writing of the 18th century ‘father’ of sadomasochism, the Marquis de Sade. Unlike other pornographers, Carter argues, de Sade was one of few to claim the ‘rights of free sexuality for women, and in installing women as beings of power in his imaginary worlds’. Her dramatization of the contrary psychology of desire is evident in The Passion of New Eve (1977), in which Carter tells a psychedelic tale of white Englishman Evelyn’s journey from sadistic desire for an African-American woman to his symbolic punishment and mythical transformation through surgery into ‘Eve’.

Carter was certainly non-binary in her fantastical imaginings – Eve/Evelyn at one point confesses, ‘Masculine and feminine are correlatives which involve one another. I am sure of that – the quality and its negation are locked in necessity. But what the nature of masculine and nature of feminine might be, whether they involve male and female, […] I do not know’ (149-150). Feminist fantasy allows big questions to be asked about what a women-emancipated or gender fluid world could look like, as well as what would happen if our oppressive ways of living get even more out of control. Carter’s play with transgendered as well as feminist plots encourages us to look closely at whether today’s vampire romances and video game neo-gothicism are as bold and generous.

Doing it for ourselves: Virago, The Women’s Press and the radical book trade

Activists also challenged patriarchal culture through creating their own publishing houses, lists, bookshops, fairs and festivals.[5] The pleasure and skill involved is hard to imagine today when digital technology has so democratized these processes. But for many such as some-time printer Gail Chester, publisher Carmen Callil and editor Ursula Owen, women were seizing the means of cultural production. Publishers Sheba, Onlywomen, Pandora, New Beacon Books, Allison and Busby, and most famously Virago Press, were key players in promoting feminist writing.

And as radical booksellers, feminists joined anarchist, left, black and ‘third world’, gay and lesbian, Irish and green communities, to create an alternative public sphere, in its way as comforting as today’s bookstore-coffee shops. Virago nurtured important non-fiction – including Amrit Wilson’s Finding a Voice: Asian Women in Britain (1978), Stella Dadzie, Beverly Bryan and Suzanne Scafe’s Heart of the Race: Black Women’s Lives in Britain, (1985) and Beatrix Campbell’s The Iron Ladies: Why do Women Vote Tory? (1987). These, as well as its reprints of African-American best sellers such as Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, opened up the diversity of women’s struggles and songs.

Virago also ingeniously connected readers with women’s struggles in the past by reprinting scandalously neglected ‘Modern Classics’. Antonia White’s Frost in May, republished in 1978 after its debut in 1933, was the first, a tale of a traumatic Catholic girlhood before the First World War, while Sylvia Townsend Warner’s sly portrait of a rebellious aunt-witch in the 1920s, Lolly Willowes (republished 1978), has recently been championed by Sarah Waters, whose gripping lesbian historical novels will undoubtedly be Virago classics themselves for as many decades to come.

Magazines, protest and pleasure

Virago was inspired by one of movement’s sparkliest productions – Spare Rib. Founded by Marsha Rowe and Rosie Boycott in 1972, this monthly magazine reinvented the popular woman’s glossy from a feminist perspective. It included articles on lifestyle, fashion, relationships and work aspirations – but all rooted in deep analyses of whether these enabled women genuine choices, and as importantly, solidarity and equality with each other. By the time it folded in 1993, over 4,300 writers and artists had contributed, with cartoons, artworks, photographs, music reviews, as well as new fiction, poetry and journalism. Jill Nicholls, collective member 1974–1980, saw it as a work of art in itself, and certainly its design was funky and fun. Spare Rib opened up the movement to a wider readership, although walking a narrow line between pleasure and the political points it wanted to make.

Footnotes

[1] Joannou, Maroula, and Imelda Whelehan, ‘This Book Changes Lives: The ‘Consciousness-Raising Novel’ and Its Legacy’, The Feminist Seventies, ed. by Helen Graham (York: Raw Nerve Books, 2003), pp. 125–40.

[2] Niamh Baker, Happily Ever After? Women’s Fiction in Postwar Britain 1945–60 (London: Macmillan Education, 1989)

Linda R Anderson, Plotting Change : Contemporary Women’s Fiction (London: Edward Arnold, 1990).

[3] Helen Carr, From My Guy to Sci-Fi : Genre and Women’s Writing in the Postmodern World (London: Pandora Press, 1989).

[4] Hera Cook, ‘Angela Carter’s “The Sadeian Woman” and Female Desire in England 1960–1975’, Women’s History Review, 23.6 (2014), pp. 938–56.

[5] See the British Library’s Women in Publishing project and Talking Print: Oral History of the Book Trade <https://www.bl.uk/collection-guides/oral-histories-of-writing-and-publishing> [accessed May 2016]

[6] Alicia Ostriker, Stealing the Language: The Emergence of Women’s Poetry in America (London: Women’s Press, 1987, 1986).

[7] Rosalind Coward, ‘“This Novel Changes Lives”: Are Women’s Novels Feminist Novels? A Response to Rebecca O’Rourke’s Article “Summer Reading”’, Feminist Review, 5 (1980), pp. 53–64.

[8] Denise Riley, ‘Does a Sex Have a History’, New Formations, 1.1 (1987), pp. 35–45.

[9] Mary Eagleton, Working with Feminist Criticism (Oxford: Blackwell, 1996).

[10] Janice A Radway, Reading the Romance: Women, Patriarchy and Popular Literature, (London: Verso, 1987, 1984).

Helen Taylor, Scarlett’s Women: Gone with the Wind and Its Female Fans (Virago, 1989).

[11] Sandra M Gilbert, The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth Century Literary Imagination, ed. by Susan Gubar (Yale University Press, 1979).

Elaine Showalter, ‘Gilbert & Gubar’s the Madwoman in the Attic after Thirty Years, Edited by Annette R. Federico (Book Review)’ (2011) Vol. 53, pp. 715–17.

[12] Can the Subaltern Speak?: Reflections on the History of an Idea, ed. by Rosalind C Morris (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010).

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’, Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, eds. Clary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988), pp. 271–316.

[13] Judith Wilt, Abortion, Choice, and Contemporary Fiction: The Armageddon of the Maternal Instinct (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990).

Tess Cosslett, Women Writing Childbirth: Modern Discourses of Motherhood (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1994).

[14] Susheila Nasta, Motherlands: Black Women’s Writing from Africa, the Caribbean and South Asia (London: Women’s Press, 1991).

[15] Laura Mulvey, ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’, Screen, 16.3 (1975), pp. 16–13.

Laura Mulvey, ‘Afterthoughts on “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” Inspired by Duel in the Sun‘, Feminism and Film Theory, ed. by Constance Penley (New York: Routledge, 1988), pp. 57–68.

[16] Paulina Palmer, Contemporary Women’s Fiction: Narrative Practice and Theory (Hemel Hempstead: Harvester, 1989).

[17] Karla Jay and Joanne Glasgow, Lesbian Texts and Contexts : Radical Revisions (London: Onlywomen Press, 1992).

Emma Donoghue, Passions between Women: British Lesbian Culture 1668–1801 (London: Scarlet, 1993).

[18] Linda Anderson, Women and Autobiography in the Twentieth Century: Remembered Futures (Hemel Hempstead, Herts: Prentice Hall/Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1997).

Sidonie Smith and Julia Watson, Women, Autobiography, Theory: A Reader. Wisconsin Studies in American Autobiography (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1998).

Sidonie Smith and Julia Watson, Reading Autobiography: A Guide for Interpreting Life Narratives, 2nd ed. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010).

Media Attributions

- 1024px-Caspar_David_Friedrich_-_Wanderer_above_the_sea_of_fog

- Hurston-Zora-Neale-LOC

- 1024px-Punch_Rhodes_Colossus

- O22_Doris_Lessing