Research Methodology

10 Methodological Considerations When Setting up Research

When conducting sensory tests, the quality of the results largely depends on the study design. Critical issues to consider are blinding and coding, randomisation, order effects, and frame of reference. As you learned in the chapter Multimodal Interactions, people form expectations about the taste based on other cues, for example, the colour or description of the food.

To lower these effects during sensory testing, samples are standardised and blinded before they are judged. All cues that can affect evaluation and are not under investigation are kept as constant as possible (standardisation). For example, the temperature, colour, and the amount of sample (volume or grams).

Furthermore, no information is given about the differences between the food samples, and samples are often labelled with non-informative numbers and/or letters. The labelling is done using codes that are not retraceable to the manipulation or the order of manipulation. So, for example, a random 3-digit code, which only the researchers can interpret.

Order effect

Many factors affect the evaluation of a panellist. The order in which they receive the samples may affect their evaluation. This is the so-called order effect.

The order effect caused by multiple factors:

- Adaptation. Sensory receptors may become less sensitive after continuous exposure to a stimulus, affecting the perception of later samples;

- Contrast effects. The perception of a sample can be influenced by the sample tested before it;

- Expectation. Panellists might develop expectations based on the order of presentation, which can bias their responses;

- Fatigue. Sensory fatigue can occur if panellists are exposed to too many samples in a brief period, this may lead to imprecise evaluations;

- Memory. Panellists might remember earlier samples and compare them, rather than evaluating each sample independently. The first sample can set a reference for the samples that are tasted later.

Frame of reference

Imagine you have four different samples that are increasing in sweetness level. Depending on the order in which you receive these samples, you will use the scale that is presented differently.

If you get the least sweet sample first, you may score this in the middle of the scale, as you do not know that the next samples will be sweeter. But what if you get the sweetest sample first? You may also put this in the middle of the scale (as you may not know that the others are all less sweet).

So, the first sample sets expectations for the rest of the samples. To exclude order effects, you therefore randomise the order in which panellist receive the samples. This leads to random error and will not systematically affect your results.

Another strategy to deal with the effect of the first sample is by introducing one or more so-called warm-up samples. This is a sample that can help set a standardised frame of reference for all panellists; it is given to each panellist before the study starts so that they all have the same starting point.

When it is crucial for your research to fully cut the order effect, you can train the panellists on how to use the scale. However, this is not an easy task and to implement in properly it requires a lot of extra work (see chapter 14. Training a Sensory Panel).

In addition to the frame of reference that is formed by the testing design, the panellists also have a frame of reference that is caused by their eating habits. For example, people who eat more sweet foods may rate differently compared to people who do not. More about the taste of diets will be explained in chapter 19. Dietary Taste Patterns.

Sample volume

As mentioned, a concern during tasting sessions is sensory fatigue — a reduced ability to sense slight differences after tasting a lot of samples. To prevent this as much as possible, make sure that the samples and your questionnaire do not require large volumes of tasting. Around 10-20 mL of a solution may already be enough to judge taste intensity.

Typically, sensory panellists can taste up to 40 small samples, but this also depends on the number and complexity of the evaluations. To ensure valid and decent quality data, find a balance in your study design between the number of panellists, the number of questions, and the number of samples.

testing context

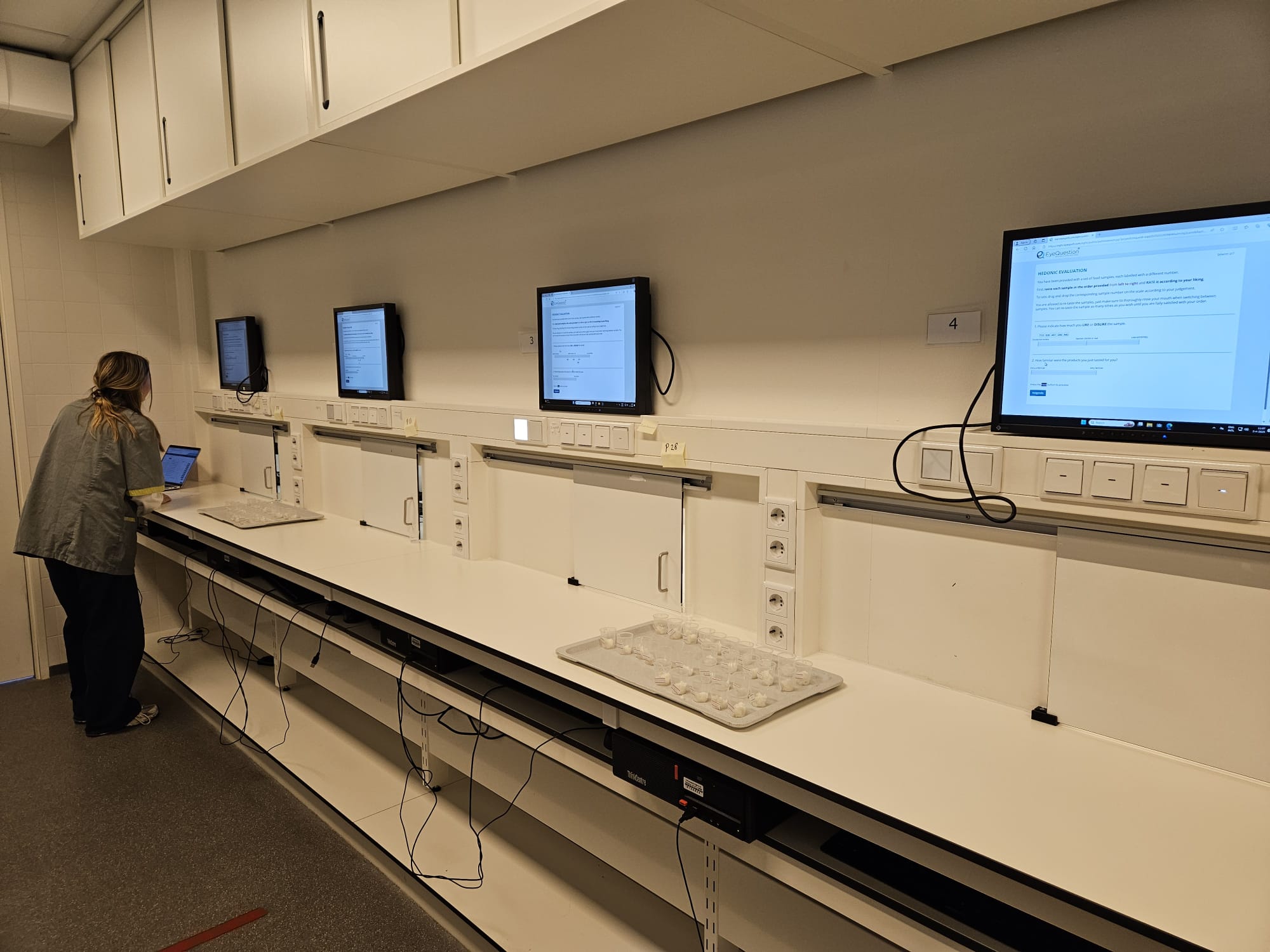

As mentioned before, the context in which samples are tested affects their evaluation. Testing in a controlled laboratory setting will standardise the context. See Figures 9, 10, and 11 for images of the sensory lab at the Helix building of Wageningen University & Research, found in Wageningen, the Netherlands.

The sensory lab in Wageningen comprises of a food grade research kitchen and a separate non-food grade bench where samples with strong odours can be made under a ventilated hood. A refrigerator, microwave and water bath are present to that samples can be heated and served at standardised temperature.

Testing takes place in five sensory booths with adjustable lighting. The testing room is air-conditioned and slightly over-pressurised, which means that strong odours from adjacent rooms cannot enter the sensory lab.

Figure 9. Odour lab, used to prepare samples with strong odours. Note that the preparation of odour samples may not be food grade and that a fume hood is critical. “WUR, SSEB – Odour lab”. License: Creative Commons Attribution

Figure 10. “WUR, SSEB -Sensory booths, participant’s side”. License: Creative Commons Attribution

Figure 11. “WUR, SSEB -Sensory booths while participants taste”. License: Creative Commons Attribution

the order in by which participants receive the sample may affect the response

Sensory adaptation refers to the process where our sensory systems become less sensitive to constant stimuli.

the inability or decreased ability to perceive a taste or odor. This increases over time as exposure continues. For example, an odor may initially be strongly detectable but can diminish completely in minutes.

A sample that is used to make participants acquainted with the sensory test. This sample is the same for all participants.

A frame of reference is the individual set of beliefs or ideas on which people base their judgment of things.