Introduction: An Open Educational Resource on Sexuality Social Justice

What is Sexuality Social Justice?

Sexuality social justice emphasizes the notion that all people, regardless of their sexual and gender identities, sexual health status or related behaviors, deserve equitable access to societal opportunities and equalities. Any acts intended to restrict or diminish this access represents a violation of sexuality social justice (Galarza & Anthony, 2015). Furthermore, the impacts of systemic oppression such as white supremacy and racism on individual and community experiences of sexuality and gender creates additional challenges for individuals navigating needed resources, support, and affirmation (Kattari, Walls, Whitfield, & Langenderfer-Magruder, 2015; McConnell, Janulis, Phillips, Truong, & Birkett, 2018).

As we noted in our 2015 publication focused on sexuality social justice (Galarza & Anthony, 2015), there is a great need for social workers and other helping professionals to increase comfort with topic areas related to human sexuality. Some educators hesitate to adopt a sex educator lens and role in the classroom or in spaces where learning occurs (Ballan, 2008). Unfortunately, this often means the impact of sexuality social justice and the intersections of racial justice on individual, family, group, and community levels of practice is rarely discussed (Turner, Vernacchio, & Satterly, 2018). However, sexuality and social justice are inherently linked; sexuality is increasingly a human rights related concern that cannot be continuously swept aside (Berer, 2004; Parker, di Mauro, Filiano, Garcia, Muñoz-Laboy, & Sember, 2004; Weeks, 2010). Just tune into your preferred news source or social media platform to observe the unraveling of essential legislation that has upheld abortion access and reproductive rights or the creation of legislation to reinenforce heteronormative, white supremacist discourse in schools.

None of this is new. Abortion has been a hotly contended subject throughout history. The rights of queer and sexually minoritized communities have been the focus of harmful litigation by countless federal, state, and local administrations. In this world we live in, people aim to harm communities in an effort to uphold oppressive systems that prioritize and center white, cisgender, heteronormative, able bodied, Christian values.

Although people are encountering and observing these issues in society, these topics are still considered too taboo to intentionally integrate into classroom discussions or related spaces; therefore, the right sources are needed to help people work through this material. There is still a great need for resources that directly relate to gender, sexuality, and the helping professions. There are few text options available that focus on this content, as well as take an intersectional approach (Bywater & Jones, 2008; Satterly & Ingersoll, 2019). Furthermore, there are very few open access educational resources that would make this content more accessible, which lends to a social injustice.

Frameworks

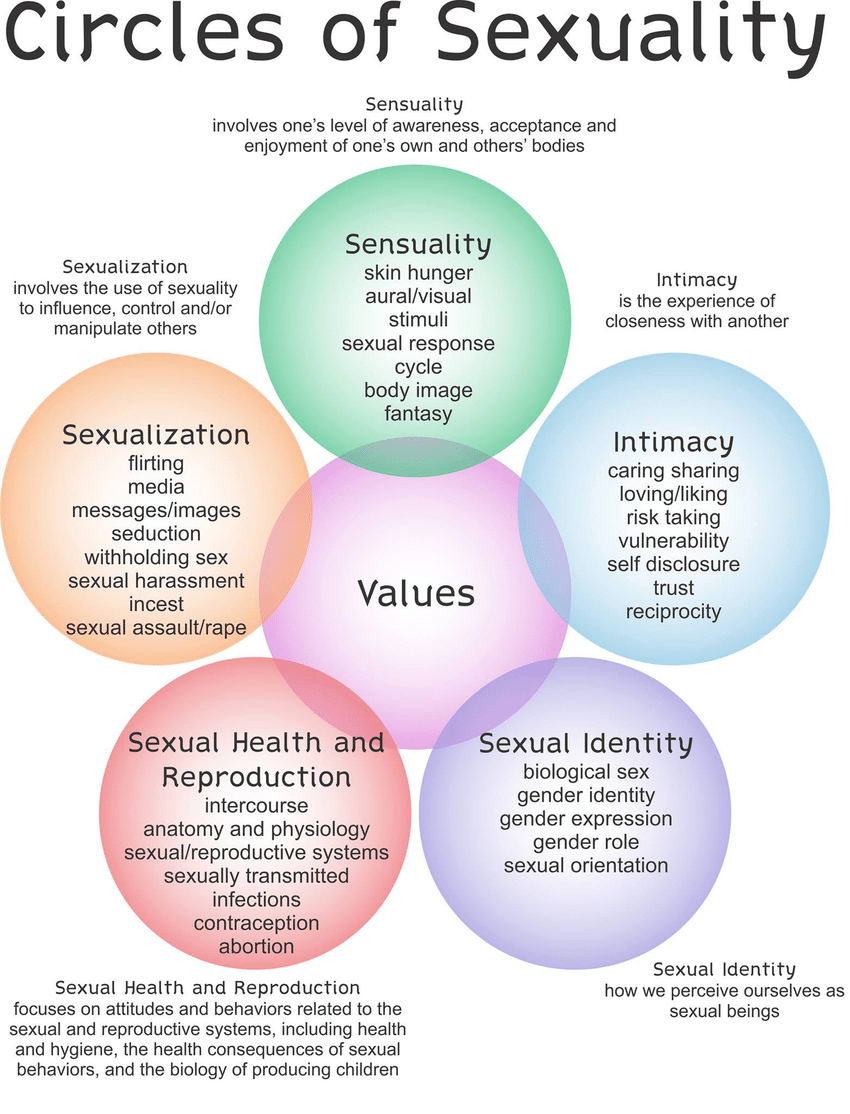

In conceptualizing this project, we knew the frameworks supporting this work would need to reflect the overall goal of providing a more inclusive lens and discussion of sexuality social justice. With that in mind, this text applies an intersectional framework (Crenshaw, 1991), as well as utilizes the Circles of Sexuality model (Dailey, 1981), and Conflict in Sexuality Education Model (Gilbert, Galarza, & McKee, 2019) to guide the selection of topics and, ideally, the subsequent discussions that would emerge from reading these works.

Intersectionality

We frame this work within theories of intersectionality. Intersectionality highlights the inextrictability of different axes of oppression (Crenshaw, 1990). Rather than viewing issues as just racism or sexism, just heterosexism or ableism, intersectionality argues that these systems are co-constructed and co-maintained within a “matrix of domination” (Collins, 1990; Hancock, 2015). To understand how sexuality is oppressed, regulated, and produced, we have to analyze the ways in which white supremacy, colonialism, and cissexism have structured society.

Sex has been used as a tool of violence to subjugate Black, Indigenous, and other marginalized peoples (hooks, 1984; Roberts, 1998). Sexuality has been regulated to sanction certain types of relationships and punish others (Sommerville, 2000; Mogul, Ritchie, & Whitlock, 2012). Reproductive health has been produced out of nonconsensual, non-anesthetized experimentation on Black women’s bodies (Roberts, 1998; Washington, 2008; Owens, 2018). Intersex babies have been robbed of their bodily autonomy and, for many, their potential to experience genital pleasure later in life (Chase, 1998). Through these acts and more, sexuality has been materially produced out of intersecting histories of violence that cannot be understood without a more concrete analysis of the political, social, historical, and economic conditions that frame the entirety of human life. Simultaneously, amidst oppression and repression, marginalized peoples have found ways to resist, create spaces where they can more freely exist, and bask in the pleasures of sex and sexuality.

At least as far back as 1851, intersectionality was beginning to be framed within larger discussions of race, gender, and class. At the 1851 Women’s Rights Convention, formerly enslaved abolitionist and women’s rights activist, Sojourner Truth, gave her famed speech, “Ain’t I A Woman,” in which she pointed to the different experiences of white and Black women due to the material conditions of enslavement. In 1892, sociologist Anna Julia Cooper wrote of the intersecting oppression Black women in the Southern United States faced in the U.S. and the dangers that Black women faced as both Black and woman within a segregated nation. In 1921, within the newly birthed Soviet Union, Alexandra Kollontai urged a changing of sexual relations that were born out of a capitalist system depriving working-class women of their right to work, education, and political development. Later in the 1950s, ‘60s, and ‘70s, amidst a nationwide surge of radical movements, Black, Asian American, Chicana, Indigenous, and working-class women called for a struggle that recognized the “double” or “triple” oppression that they experienced and to fight for a world in which all forms of oppression no longer exist (Jones, 1950; Beal, 1969; Combahee River Collective, 1977). Later, in the 1990s, legal scholar, Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term “intersectionality” to highlight the multiplicitous ways in which various forms of oppression converge to create distinct forms of exploitation of and violence against Black women and other women of color.

We frame this text within this legacy of work so that: 1) students may better understand how racism, sexism, heterosexism, ableism, and other forms of oppression function hand-in-hand, producing different mechanisms through which individuals are oppressed; and 2) students may use this knowledge to move forward, putting theory into action, to fight in such a way that all forms of oppression are simultaneously challenged. As Black, lesbian, feminist, socialist, mother, warrior, poet, Audre Lorde wrote, “There is no such thing as a single issue struggle, because we do not live single-issue lives” (1984, p. 138). We cannot move forward without one another, because our oppression is connected. Our exploitation is connected. So we have to fight together.

Circles of Sexuality

The Circles of Sexuality (Dailey, 1981) is a holistic framework for approaching and understanding the complexities of sexuality. Dennis Dailey first created the Circles of Sexuality in 1981. The five circles include: Sexual and gender identities, sexual health and reproduction, sexualization, sensuality, and intimacy. Since 1981, various authors (Turner, 2020; Advocates for Youth, 2007; Ingersoll & Satterly, 2019) have adapted it over the years to reflect changes in terminology as well as to further broaden some of these areas. An additional circle was created by Satterly and Dyson (2010), entitled values. This circle is used to represent one’s own “lens by which a person perceives, interprets, and understands all the other Circles” (Ingersoll & Satterly, 2019, p.13). Turner’s 2020 figure helps us explore the various circles by defining each circle and noting what topics are included in each one.

Figure 1: Circles of Sexuality

(Turner, 2020)

Note. Adapted from “Rooted in Strengths: Celebrating the Strengths Perspective in Social Work” by Mendenhall, A.N and Carney, M.M., 2020, p. 314 (https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/handle/1808/30023). CC BY-NC 4.0.

As you review Figure 1: Circles of Sexuality, please pay attention to your own reactions. Did your physical body tense up at any of the terms? Are any of the terms new to you? Are you curious about learning more? What topics are you surprised by? What, if at all, does this differ from your own experiences learning about human sexuality?

We constructed this text within the Circles of Sexuality framework so that: 1) students better understand how comprehensive sexuality is; 2) students will think about their own experiences within the circles of sexuality and specifically, how their values have shaped own understanding and meaning of sexuality concepts; and 3) students will recognize how human sexuality is part of what it means to be a person.

We recognize that although the Circles of Sexuality is a comprehensive model, the selection of topics in this work is not all encompassing. We acknowledge there may be subject areas that have been missed. This work is just the beginning of much needed conversations and will be expanded on in future editions.

Conflict in Sexuality Education Model

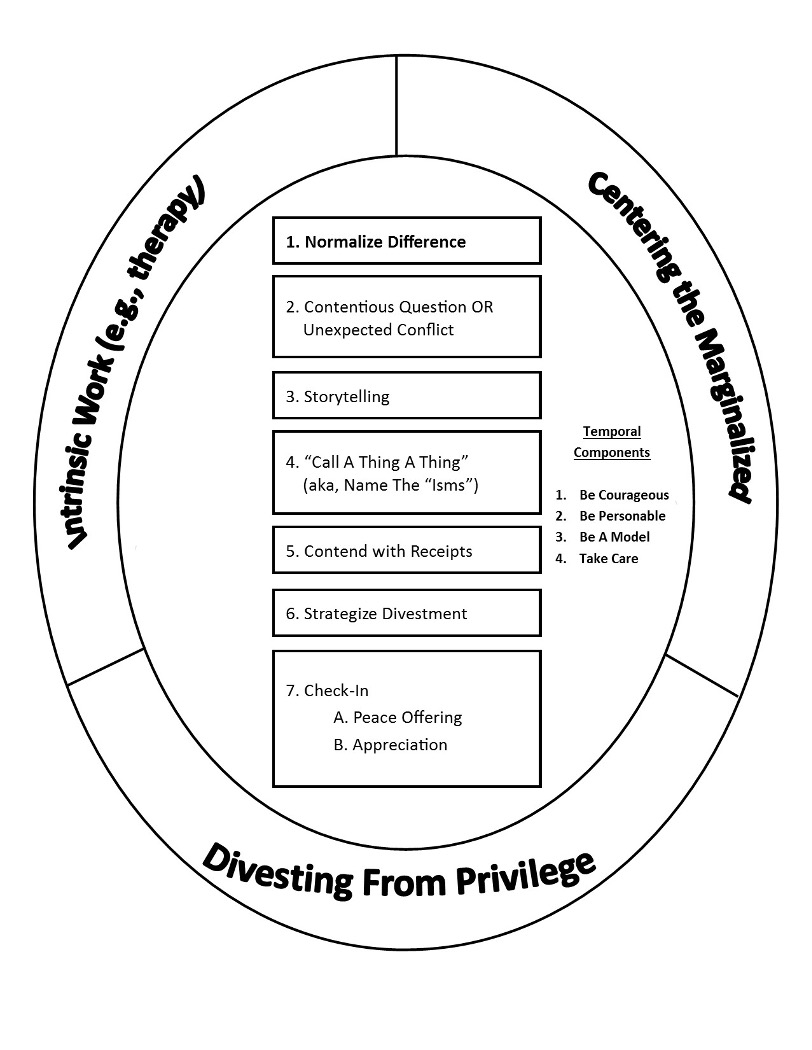

In order to help readers cultivate effective teaching strategies for facilitating discussions that may emerge from reading these chapters, we also wanted to share the Conflict In Sexuality Education (CISE) Model (Gilbert, Galarza, & Mckee, 2019) as a valuable resource and foundation for this work.

Drs. Gilbert, Galarza, and McKee are the co-editors of the last edition of Taking Sides: Clashing Views in Human Sexuality. Stemming from this collaboration, Drs. Gilbert, Galarza, and McKee developed and presented their CISE Model at the 2019 American Association of Sexuality Educators, Counselors, and Therapists (AASECT) annual meeting. Based on their extensive teaching experiences in sex education, insights gained from challenges and successes with addressing conflict in the classroom, this model was conceptualized to help others navigate these experiences. The CISE Model offers educators and students who are pursuing careers in sex education, as well as related fields, important considerations for addressing conflict in learning spaces.

As outlined in figure 2 shared below, these components are:

The outer circle emphasizes what is needed before engaging in this work as professionals and includes: Intrinsic work, divesting from privilege, and centering the marginalized. In order to set the stage for these conversations, facilitators must be in a point of their own learning and work to move forward. You should ask yourself: Have I done my own work–identified areas for growth, potential triggers, unlearned internalized narratives that are byproducts of oppressive systems, etc.? Have I fully divested myself from privilege–not simply identifying points of privilege but interrogating the systems in which they were produced and making meaningful changes to undo, unlearn, and relearn? Am I at the point of my work where I am intentional about centering the stories, experiences, and voices of minoritized communities?

The inner circle outlines consideration for navigating conflict in learning spaces. This includes: Normalizing difference, contentious question or unexpected conflict, storytelling, “call a thing a thing,” contend with receipts, strategize divestment, check-in. These are all aspects of the facilitation process and may emerge at various points in the process. Facilitators should anticipate differences will emerge whenever these topics are presented. We all have a story and we enter these spaces without fully grasping what others are holding onto. Therefore, it is important to normalize while also realizing it will also produce feelings of discomfort. As a facilitator, you may make the decision to introduce a contentious question in order to spark conflict or this may happen in a more spontaneous and unexpected way. Regardless of how it manifests, we are left with the question–what do we do with this now? This is when we rely on storytelling–speaking from our truth and not intellectualizing thoughts and feelings (and this is another way of centering minoritized voices); name what is happening–call a thing a thing and recognize and normalize discomfort around this; contend with receipts–what’s the evidence?; strategize divestment–just as we must do this prior to our facilitation, we must help participants navigate this as well–how do you move from a place of privilege or standing firmly in all you’ve known and truly undoing all of this in order to move into a space of real understanding and systemic/personal change? And, finally, check in–identify and name the feelings, express appreciation, consider ways for leaving a little more whole than when in the thick of it.

And the temporal components i.e. what’s needed as you move forward with and remain engaged in this process, and these are: Be courageous, be personable, be a model, and take care. In some ways, the temporal pieces connect back to those pieces from the outer circle–what do I need to work on in order to be able to move forward with this from a place of courage, connection, and compassion–both for myself as well as those I am sharing space with?

Although at a first glance this appears to be a linear process, people are encouraged to look at this and apply it as a circular process, hence the imagery of a circle. Folks may already enter the space with a solid understanding of themselves; however, through the course of the learning experience, there may be a need to return to this for additional personal work. In addition, it is also important to consider the identities of facilitators and how this may impact and complicate facilitation of these types of conversations. This must also be named at the beginning and acknowledged through processing this work.

This model is applicable to this current work because as you will come to understand, many of these topics are considered divisive. Rather than engage in difficult yet meaningful discussions, people will often either avoid altogether or proceed without any consideration for the elements that could lead to more effective, evolved understandings of each other and these topics. This model is not considered an absolute solution to navigating all conflicts that will emerge in learning spaces; however, it helps fill a gap not often addressed within teaching practices.

Figure 2: Conflict in Sexuality Education Model

Note. From Conference Presentation, by Gilbert, T. Galarza, J. & McKee, R. Copyright 2019 by authors. Reprinted with permission.

Book Goals

- To help expand understanding of sexuality and related topics while applying an intersectional, social justice lens

- To introduce relevant theories and knowledge areas as well as affective processing components

- To provide strategies for application in future practices

- To include stories/narratives/voices that are often not included in traditional publishing methods

Why Open Access?

The costs of academic textbooks is a social justice issue. Sixty-five percent of the college students surveyed in 2020 reported not buying a textbook due to cost (U.S. PIRG Education Fund, 2021). Not being able to access their materials creates additional barriers to furthering education for many students, especially in the United States of America where textbook and tuition costs continue to rise.

In addition to costs that limit access, we note that interconnected systems of oppression and white supremacy culture have influenced what is considered knowledge, whose voice is valued, who is considered an expert and therefore, have increased access and are able to disseminate information through more traditional academic publishing venues. These factors have greatly impacted the type of human sexuality knowledge that is accessible to our students. For these reasons, we were intentional in how we wanted to proceed in publishing a comprehensive book focused on sexuality social justice.

Our goal is to increase access to the type of information that is often left for the margins of academia, designated as “special topics,” passively talked about in classrooms, or the subjects of poorly attended campus events. We want to reach a wider audience and provide a catalyst for more engaging conversations. We also want to provide a platform for authors to share in ways that are often limited by standards placed by academic journals and publishing companies. If the goal is to increase knowledge, we need to start with dismantling and disrupting the existing systems that often serve as architects and guardians of the ivory tower.

Open Educational Resources (OERs) are resources created for learning that are open and freely available. Many OERs, including this one, are released under an open license that allows others to freely use and share materials. We encourage students, professors, and anyone interested in this book to read, share, engage, and ENJOY the chapters covered in this book. By eliminating the costs associated with this text, we are taking a step toward the type of meaningful change we hope to see.

If you are utilizing this book for a class or you want to share your overall thoughts and provide input, please complete our voluntary survey by clicking on this link (include link). We value your feedback and encourage you to share with us! Please note, this survey is part of an ongoing research study to help us continue to update this book as we strive to keep it relevant, relatable, and reflective of current conversations.

Positionality Statements

Jayleen (they/them) is a queer, Puerto Rican, non-binary, often able-bodied, mother, partner, daughter, friend, scholar, educator, therapist, and activist living in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania on the unceded lands of the Susquehannock tribe. I am a first generation college graduate who grew up in a household that struggled with financial insecurity, and I was privileged in having various folks and programs, including East Stroudsburg University’s Upward Bound program, invest in my success and help me access resources that would assist me in navigating and graduating college and graduate school. I am an Associate Professor within the Social Work & Gerontology Department at Shippensburg University, which is situated on the unceded lands of the Susquehannock. I am also a co-host of a podcast focused on sex and aging called Our Better Half.

alithia is an often-able-bodied, white and Latina, transgender, heteroflexible woman living in Chicago, Illinois on the unceded lands of the Neshnabéé, Odawa, Ojibwa, Myaamia, Mamaceqtaw, and Hoocak Peoples. How I orient myself in the world is based on my upbringing in a working-class, multinational family. As an intellectual, I am based at Northwestern University, a private research university with over-access to resources and wealth. My intellectual commitments, though, are to the oppressed and working people of the world. As Walter Rodney said, “I felt that somehow being a revolutionary intellectual might be a goal to which one might aspire, for surely there was no real reason why one should remain in the academic world—that is, remain an intellectual—and at the same time not be a revolutionary.” Outside work, I am a community organizer, primarily on the South and West Sides of Chicago working to build a socialist future in which racism, cis-hetero-sexism, and all forms of oppression and exploitation no longer exist.

Becky (she/her) is an often-able-bodied, white, queer, cis-gender woman with a learning disability living in Salisbury, Maryland on the unceded lands of the Algonquin, Assateague, Choptank, Delaware, Matapeake, Naticoke, and Pocomoke Peoples. I am an Associate Professor based at Salisbury University, a public state university, in the School of Social Work. I am an AASECT certified sex therapist and I identify as a pleasure activist and anti-racist social worker and educator.

References

Advocates for Youth. (2007). Life Planning Education, https://www.advocatesforyouth.org/wp-content/uploads/storage/advfy/documents/circles.pdf

Ballan, M.S. (2008). Disability and sexuality within social work education in the USA and Canada: The social model of disability as a lens for practice. Social Work Education, 27(2), 194-202.

Berer, M. (2004). Sexuality, rights, and social justice. Reproductive Health Matters, 12(23), 6- 11.

Bywater, J. & Jones, R. (2008). Sexuality and Social Work. Learning Matters.

Chase, C. (1998). “Surgical Progress is not the Answer to Intersexuality.” The Journal of Clinical Ethics 9(4), 385-392.

Combahee River Collective. 1977. “The Combahee River Collective Statement.” Retrieved from

https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/combahee-river-collective-statement-1977/.

Dailey, D. (1981). Sexual expression and ageing. In: Berghorn D and Schafer D (eds) The Dynamics of Ageing: Original Essays on the Processes and Experiences of Growing Old. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, pp. 311–330.

Collins, P. H. (1990). Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. UK: Hyman.

Cooper, A. J. (1892). [1969]. A Voice From the South: By a Black Woman of the South. New York City: Negro Universities Press.

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review 43(6), 1241-1299. DOI: 10.2307/1229039.

Galarza, J. & Anthony, B. (2015). Sexuality social justice and social work: Implications for social work education. Journal of Baccalaureate Social Work, 20(1), 27-40. doi:10.18084/1084-7219-20.1.27

Galarza, J. McKee, R., & Gilbert, T. (June, 2019). Facilitating contention within sexuality education. Pre-conference workshop for the American Association of Sexuality Educators, Counselors, and Therapists (AASECT) annual conference. Philadelphia, PA.

Hancock, A-M. (2015). Intersectionality: An Intellectual History. London, UK: Oxford University Press.

hooks, b. (1984). Ain’t I A Woman? New York City: South End Press.

Jones, C. 1950. “International Women’s Day and the Struggle for Peace.” Political Affairs 29(3), 33-34.

Kattari, S.K., Walls, N.E., Whitfield, D.L., & Langenderfer-Magruder, L. (2015). Racial and ethnic differences in experiences of discrimination in accessing health services among transgender people in the United States. International Journal of Transgenderism, 16(2), 68-79. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2015.1064336

Kollontai, A. (1972). Sexual Relations and the Class Struggle. Retrieved from https://www.marxists.org/archive/kollonta/1921/sex-class-struggle.htm.

Lorde, A. (1984). Sister Outsider. Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press.

McConnell, E.A., Janulis, P., Phillips II, G., Truong, R., & Birkett, M. (2018). Multiple minority stress and LGBT community resilience among sexual minority men. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 5(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000265

Mogul, J. L., Ritchie, A. J., & Whitlock, K. (2012). Queer (In)Justice: The Criminalization of LGBT People in the United States. New York City: Beacon Press.

Owens, D. C. (2018). Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

Parker, R. (2007). Foreword. In N. Teunis, & G. Herdt (Eds.), Sexuality inequalities and social justice (pp. ix-xiv). Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

Roberts, D. (1998). Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty. New York City: Vintage Books.

Satterly, B. & Ingersoll, T. (2019). Sexuality Concepts for Social Workers (2nd ed.). Cognella Academic Publishing.

Sommerville, S. (2000). Queering the Color Line. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Truth, S. (1851). “Ain’t I A Woman?” Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/articles/sojourner-truth.htm.

Turner, G. (2020). The Circles of Sexuality: Promoting a Strengths-based Model Within Social Work that Provides a Holistic Framework for Client Sexual Well-being. In Mendenhall, A. & Carney, M.M. (Eds), Rooted in Strengths: Celebrating the Strengths Perspective in Social Work (pp.305-325). Publisher: Univ of Kansas Libraries. https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/handle/1808/30023

Turner, G. W., Vernacchio, A., & Satterly, B. (2018). Sexual justice is social justice: An activity to expand social work students’ understanding of sexual rights and injustices. Journal of

Teaching in Social Work, 38(5), 504-521. doi:10.1080/08841233.2018.1523825

U.S. PIRG Education Fund. (2021). Fixing the broken textbook market (3rd ed). https://publicinterestnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Fixing-the-Broken-Textbook-Market-3e-February-2021.pdf

Washington, H. A. (2008). Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present. New York City: Anchor Press.

Weeks, J. (2010). Making the human gesture: History, sexuality, and social justice. History Workshop Journal, 70(1), 5-20.