1

Chapter Outline

- How do educators know what to do? (12 minute read)

- The scientific method (16 minute read)

- Evidence-based practice (11 minute read)

- Education research (10 minute read)

Content warning: Examples in this chapter contain references to school discipline, food insecurity, homelessness, poverty and anti-poverty stigma, anti-vaccination pseudoscience, autism, trauma and PTSD, ADHD, mental health stigma, Brain fag syndrome (BFS), and culture-bound syndromes, gender-based discrimination at work, homelessness, psychiatric hospitalizations, substance use, and mandatory treatment.

1.1 How do educators know what to do?

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Reflect on how we, as educators, make decisions

- Differentiate between micro-, meso-, and macro-level analysis

- Describe the concept of intuition, its purpose in education, and its limitations

- Identify specific errors in thinking and reasoning

What would you do?

Case 1: You are a middle grades English teacher and the school year just recently started. You have been working with your new class for about a month and have gotten to know the students reasonably well. One student concerns you. You’ve noticed their reading and writing abilities are a few grade levels behind their peers. They are a gifted athlete and have already missed a couple of classes for athletic events. While the student pays scant attention to the assigned readings, when you do have free reading time, you note that the student often spends the time immersed in sports magazines and the sports section of the local newspaper.

- Given your observations of your student’s strengths and challenges, what intervention would you select, and how could you determine its effectiveness?

Case 2: Imagine you are a teacher working in the midst of an urban food desert (a geographic area in which there is no grocery store that sells fresh food). As a result, many of your low-income students either eat takeout, or rely on food from the dollar store or a convenience store. You are becoming concerned about your students’ health, as many of them are obese and say they are unable to buy fresh food. Your students tell you that their families rely on food pantries. You have spent the past month building a coalition of teachers and parents to lobby your city council. The coalition includes individuals from non-profit agencies, religious groups, and healthcare workers.

- How should this group address the impact of food deserts in your community? What intervention(s) do you suggest? How would you determine whether your intervention was effective?

Case 3: You are a policy analyst working at a public policy center whose work focuses on the issue of child homelessness. Your city is seeking a large federal grant to address this growing problem and has hired your agency as a consultant to work on the grant proposal. After interviewing individuals who are homeless and conducting a needs assessment in collaboration with local social service agencies, you meet with city council members to talk about potential opportunities for intervention. Local agencies want to spend the money to increase the capacity of existing shelters in the community. In addition, they want to create a transitional housing program at an unused apartment complex where families can reside upon leaving the shelter, and where they can gain independent living skills. On the other hand, homeless families you interview indicate that they would prefer to receive housing vouchers to rent an apartment in the community and gain access to different schools. They also fear the agencies running the shelter and transitional housing program would impose restrictions and unnecessary rules and regulations, thereby curbing their ability to freely live their lives. When you ask the agencies about these client concerns, they state that these clients need the structure and supervision provided by agency support workers.

- Which kind of program should your city choose to implement? Which is most likely to be effective and why?

These case studies each cover different levels of analysis in the social ecosystem—micro, meso, and macro. At the micro-level, you examine the smallest levels of interaction; in some cases, just “the self” alone (e.g. the child in case one).

When educators investigate groups and communities, such as our food desert in case 2, their inquiry is at the meso-level.

At the macro-level, you examine social structures and institutions. Research at the macro-level examines large-scale patterns, including culture and government policy.

These three domains interact with one another, and it is common for a research project to address more than one level of analysis. For example, you may have a study about individuals in a classroom (a micro-level study) that impacts the school as a whole (meso-level) and incorporates policies and cultural issues within the district (macro-level). Moreover, research that occurs on one level is likely to have multiple implications across domains.

How do educators know what to do?

Welcome to education research. This chapter begins with three problems that educators might face in practice, and three questions about what they should do next. If you haven’t already, spend a minute or two thinking about the three aforementioned cases and jot down some notes. How might you respond to each of these cases?

We assume it is unlikely you are an expert in the areas of literacy instruction, community responses to food deserts, and homelessness policy. Don’t worry, we’re not either. In fact, for many of you, this textbook will likely come at an early point in your graduate education, so it may seem unfair for us to ask you what the ‘right’ answers are. And to disappoint you further, this course will not teach you the ‘right’ answer to these questions. It will, however, teach you how to answer these questions for yourself, and to find the ‘right’ answer that works best in each unique situation.

Assuming you are not an experienced practitioner in the areas described above, you likely used intuition (Cheung, 2016).[1] when thinking about what you would do in each of these scenarios. Intuition is a “gut feeling” about what to think about and do, often based on personal experience. What we experience influences how we perceive the world. For example, if you’ve worked with reluctant readers, you may have perceived that the child in case one might benefit from a reading intervention focused on tapping into his demonstrated interest in sports. As you think about problems such as those described above, you find that certain details stay with you and influence your thinking to a greater degree than others. Using past experiences, you apply seemingly relevant knowledge and make predictions about what might be true.

Over a teacher’s career, intuition evolves into practice wisdom. Practice wisdom is the “learning by doing” that develops as a result of practice experience. For example, a teacher may have a “feel” for why a particular curricular approach would work with the high achieving students in their classroom while another approach would help struggling students engage more deeply with the content. This idea may be informed by direct experience with similar situations, reflections on previous experiences, and any consultation they receive from colleagues and/or staff resources. This “feel” that teachers get for their practice is a useful and valid source of knowledge and decision-making—do not discount it.

On the other hand, intuitive thinking can be prone to a number of errors. We are all limited in terms of what we know and experience. One’s economic, social, and cultural background will shape intuition, and acting on your intuition may not work in a different sociocultural context. Because you cannot learn everything there is to know before you start your career as a teacher, it is important to learn how to understand and use social science to help you make sense of the world and to help you make sound, reasoned, and well-thought out decisions.

Educators must learn how to take their intuition and deepen or challenge it by engaging with scientific literature. Similarly, education researchers engage in research to make certain their interventions are effective and efficient (see section 1.4 for more information). Both of these processes—consuming and producing research—inform the social justice mission of education.

Errors in thinking

We all rely on mental shortcuts to help us figure out what to do in a practice situation. All people, including you and me, must train our minds to be aware of predictable flaws in thinking, termed cognitive biases. Here is a link to the Wikipedia entry on cognitive biases, as well as an interactive list. As you can see, there are many types of biases that can result in irrational conclusions.

The most important error in thinking for social scientists to be aware of is confirmation bias. Confirmation bias involves observing and analyzing information in a way that confirms what you already believe to be true. We all arrive at each moment with a set of personal beliefs, experiences, and worldviews that have been developed and ingrained over time. These patterns of thought inform our intuitions, primarily in an unconscious manner. Confirmation bias occurs when our mind ignores or manipulates information to avoid challenging what we already believe to be true.

In our second case study, we are trying to figure out how to help largely high-poverty people who live in a food desert. Let’s say we have arrived at a policy solution and are now lobbying the city council to implement it. There are many who have negative beliefs about people who are “on welfare.” These people may believe individuals who receive social welfare benefits spend their money irresponsibly, are too lazy to get a job, and manipulate the system to maintain or increase their government payout.

Those espousing this belief may point to an example such as Louis Cuff, who bought steak and lobster with his benefits and resold them for a profit. However, they are falling prey to assuming that one person’s bad behavior reflects upon an entire group of people. City council members who hold these beliefs may ignore the truth about the client population—that people experiencing poverty usually spend their money responsibly and that they genuinely need help accessing fresh and healthy food. In this way, confirmation bias often makes people less capable of empathizing with one another because they have difficulty accepting alternative perspectives.

Errors in reasoning

Because the human mind is prone to errors, when anyone makes a statement about what is true or what should be done in a given situation, errors in logic may emerge. Think back to the case studies at the beginning of this section. You most likely had some ideas about what to do in each case, but where did those ideas come from. Below are some of the most common logical fallacies and the ways in which they may negatively influence an educator. Consider how some of these might apply to your thinking about the practice situations in this chapter.

- Making hasty generalization: when a person draws conclusions before having enough information. A teacher may apply lessons from a handful of previous students to an entire population of people (see Louis Cuff, above). It is important to examine the scientific literature in order to avoid this.

- Confusing correlation with causation: when one concludes that because two things are correlated (as one changes, the other changes), they must be causally related. As an example, a teacher might observe both a decrease in students test scores and the introduction of a new curriculum. However, just because two things changed at the same time does not mean they are causally related. Educators should explore other factors that might impact causality (such as a mismatch between existing assessments and the new curriculum).

- Going down a slippery slope: when a person concludes that we should not do something because something far worse will happen if we do so. For example, a teacher may seek to increase a student’s opportunity to choose their own activities in class, but face opposition from those who believe it will lead to students not meeting provincial learning standards or being appropriately prepared for post-secondary education. Clearly, this is nonsense. Changes that foster self-determination are more likely to result in engaged and motivated learners. Educators should be skeptical of arguments opposing small changes because one argues that radical changes will result.

- Appealing to authority: when a person draws a conclusion by appealing to the authority of an expert or reputable individual, rather than through the strength of the claim. You have likely encountered individuals who believe they are correct because another in a position of authority told them so. Instead, we should work to build a reflective and critical approach to practice that questions authority.

- Hopping on the bandwagon: when a person draws a conclusion consistent with popular belief. Just because something is popular does not mean it is correct. Fashionable ideas come and go. Educators should engage with trendy ideas but must ground their work in scientific evidence rather than popular opinion.

- Using a straw man: when a person does not represent their opponent’s position fairly or with sufficient depth. For example, a teacher advocating for the end of the Foundation Skills Assessment may paint the tests as overly stressful for students and damaging to their mental health. However, this may not be the case–the tests themselves may have little impact on students; however the political use of the test information may. Educators should make sure to engage deeply with all sides of an issue and represent them accurately.

Key Takeaways

- Education research occurs at the micro-, meso-, and macro-level.

- Intuition is a powerful, though limited, source of information when making decisions.

- All human thought is subject to errors in thinking and reasoning.

- Scientific inquiry accounts for cognitive biases by applying an organized, logical way of observing and theorizing about the world.

Exercises

- Think about an education topic you might want to study this semester as part of a research project. How do individuals commit specific errors in logic or reasoning when discussing a specific topic (e.g. Louis Cuff)? How can using scientific evidence help you combat popular myths about your topic that are based on erroneous thinking?

- Reflect on the strengths and limitations of your personal experiences as a way to guide your work with diverse populations. Describe an instance when your intuition may have resulted in biased or misguided thinking or behaviour in a practice situation.

1.2 The scientific method

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Define science and social science

- Describe the differences between objective truth and subjective truths

- Identify how qualitative and quantitative methods differ and how they can be used together

- Delineate the features of science that distinguish it from pseudoscience

If we asked you to draw a picture of science, what would you draw? Our guess is it would be something from a chemistry or biology classroom, like a microscope or a beaker. Maybe something from a science fiction movie. All educators use scientific thinking in their practice. However, we have a unique understanding of what science means, one that is (not surprisingly) more open to the unexpected and human side of the social world.

Science and not-science

In education, science is a way of ‘knowing’ that attempts to systematically collect and categorize facts or truths. A key word here is systematically—conducting science is a deliberate process. Scientists gather information about facts in a way that is organized and intentional, and usually follows a set of predetermined steps. Education is not a science, but it is informed by social science—the science of humanity, social interactions, and social structures. In other words, education research uses organized and intentional procedures to uncover facts or truths about the social world. And educators rely on social scientific research to promote change.

Science can also be thought of in terms of its impostor, pseudoscience. Pseudoscience refers to beliefs about the social world that are unsupported by scientific evidence. These claims are often presented as though they are based on science. But once researchers test them scientifically, they are demonstrated to be false. A scientifically uninformed teacher practitioner using pseudoscience may recommend any number of ineffective, misguided, or harmful interventions. Pseudoscience often relies on information and scholarship that has not been reviewed by experts (i.e., peer review) or offers a selective and biased reading of reviewed literature.

An example of pseudoscience comes from anti-vaccination activists. Despite overwhelming scientific consensus that vaccines do not cause autism, a very vocal minority of people continue to believe that they do. Anti-vaccination advocates present their information as based in science, as seen here at Green Med Info. The author of this website shares real abstracts from scientific journal articles and studies but will only provide information on articles that show the potential dangers of vaccines, without showing any research that presents the positive and safe side of vaccines. Green Med Info is an example of confirmation bias, as all data presented on the website supports what the pseudo-scientific researcher believes to be true. For more information on assessing causal relationships, consult Chapter 8, where we discuss causality in detail.

The values and practices associated with the scientific method work to overcome common errors in thinking (such as confirmation bias). First, the scientific method uses established techniques from the literature to determine the likelihood of something being true or false. The research process often cites these techniques, reasons for their use, and how researchers came to the decision to use said techniques. However, each technique comes with its own strengths and limitations. Rigorous science is about making the best choice, being open about your process, and allowing others to check your work. It is important to remember that there is no “perfect” study—all research has limitations because all scientific methods come with limitations.

Skepticism and debate

Unfortunately, the “perfect” researcher does not exist. Scientists are human, so they are subject to error and bias, such as gravitating toward fashionable ideas and thinking their work is more important than others’ work. Theories and concepts fade in and out of use and may be tossed aside when new evidence challenges their truth. Part of the challenge in your research projects will be finding what you believe about an issue, rather than summarizing what others think about the topic. Good science, just like good teaching, is authentic. When we see students present their research projects, those who are the strongest deliver both passionate and informed arguments about their topic area.

Good science is also open to ongoing questioning. Scientists are fundamentally skeptical. As such, they are likely to pursue alternative explanations. They might question the design of a study or replicate it to see if it works in another context. Scientists debate what is true until they arrive at a majority consensus. If you’ve ever heard that 97% of climate scientists agree that global warming is due to human activity[2] or that 99% of economists agree that tariffs make the economy worse,[3] you are seeing this sociology of science in action. This skepticism will help to catch situations in which scientists who make the oh-so-human mistakes in thinking and reasoning reviewed in Section 1.1.

Skepticism also helps to identify unethical scientists, as with Andrew Wakefield’s study linking the MMR vaccination and autism. When other researchers looked at his data, they found that he had altered the data to match his own conclusions and sought to benefit financially from the ensuing panic about vaccination (Godlee, Smith, & Marcovitch, 2011).[4] This highlights another key value in science: openness.

Openness

Through the use of publications and presentations, scientists share the methods used to gather and analyze data. The trend towards open science has also prompted researchers to share data as well. This in turn enables other researchers to re-run, replicate, and validate analyses and results. A major barrier to openness in science is the paywall. When you’ve searched online for a journal article (we will review search techniques in Chapter 3), you have likely run into the $25-$50 price tag. Don’t despair—your university should subscribe to these journals. However, the push towards openness in science means that more researchers are sharing their work in open access journals (like the International Journal of Education and Leadership), which are free for people to access (like this textbook!). These open access journals do not require a university subscription to view.

Openness also means engaging the broader public about your study. Education researchers conduct studies to help people, and part of scientific work is making sure your study has an impact. For example, it is likely that many of the authors publishing in scientific journals are on Twitter or other social media platforms, relaying the importance of study findings. They may create content for popular media, including newspapers, websites, blogs, or podcasts. It may lead to training for teachers or public administrators. Regrettably however, many academic researchers have a reputation for being aloof and disengaged from the public conversation. This reputation is slowly changing with the trend towards public scholarship and engagement. For example, the What Works Clearinghouse and ERIC Database in the U.S. was established to help educators find useful research.

Science supported by empirical data

Pseudoscience is often doctored up to look like science, but the surety with which its advocates speak is not backed up by empirical data. Empirical data refers to information about the social world gathered and analyzed through scientific observation or experimentation. Theory is also an important part of science, as we will discuss in Chapter 7. However, theories must be supported by empirical data—evidence that what we think is true really exists in the world.

There are two types of empirical data that educators should become familiar with. Quantitative data refers to numbers and qualitative data usually refers to word data (like a transcript of an interview) but can also refer to pictures, performances, and other means of expressing oneself. Researchers use specific methods designed to analyze each type of data. Together, these are known as research methods, or the methods researchers use to examine empirical data.

Objective truth

In our vaccine example, scientists have conducted many studies tracking children who were vaccinated to look for future diagnoses of autism (see Taylor et al. 2014 for a review). This is an example of using quantitative data to determine whether there is a causal relationship between vaccination and autism. By examining the number of people who develop autism after vaccinations and controlling for all of the other possible causes, researchers can determine the likelihood of whether vaccinations cause changes in the brain that are eventually diagnosed as autism.

In this case, the use of quantitative data is a good fit for disproving myths about the dangers of vaccination. When researchers analyze quantitative data, they are trying to establish an objective truth. An objective truth is always true, regardless of context. Generally speaking, researchers seeking to establish objective truth tend to use quantitative data because they believe numbers don’t lie. If repeated statistical analyses don’t show a relationship between two variables, like vaccines and autism, that relationship almost certainly does not exist. By boiling everything down to numbers, we can minimize the biases and logical errors that human researchers bring to the scientific process. That said, the interpretation of those numbers is always up for debate.

This approach to finding truth probably sounds similar to something you heard in your middle school science classes. When you learned about gravitational force or the mitochondria of a cell, you were learning about the theories and observations that make up our understanding of the physical world. We assume that gravity is real and that the mitochondria of a cell are real. Mitochondria are easy to spot with a powerful microscope, and we can observe and theorize about their function in a cell. The gravitational force is invisible but clearly apparent from observable facts, such as watching an apple fall. If we were unable to perceive mitochondria or gravity, they would still be there, doing their thing, because they exist independent of our observation of them.

Let’s consider an education example. Scientific research has established that children who are subjected to severely traumatic experiences are more likely to be diagnosed with a mental health disorder (e.g., Mahoney, Karatzias, & Hutton, 2019).[5] A diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is considered objective, and may refer to a mental health issue that exists independent of the individual observing it and is highly similar in its presentation. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5, 2017)[6] identifies a group of criteria which is based on unbiased, neutral student observations. These criteria are based in research, and render an objective diagnosis more likely to be valid and reliable. Through the clinician’s observations and the student’s description of their symptoms, an objective determination of a mental health diagnosis can be made.

Subjective truth(s)

For those of you who are skeptical, you may ask yourself: does a diagnosis tell a student’s whole story? No. It does not tell you what the student thinks and feels about their diagnosis, for example. Receiving a diagnosis of ADHD may be a relief for a student. The diagnosis may suggest the words to describe their experiences. In addition, this diagnosis may provide a direction for therapeutic work, as there are evidence-based interventions teachers can use with such a diagnosis. On the other hand, a student may feel shame and view the diagnosis as a label, defining them in a negative way and limiting their potential (Barsky, 2015).[7]

Imagine if we surveyed people with ADHD to see how they interpreted their diagnosis. Objectively, we could determine whether more people said the diagnosis was, overall, a positive or negative event for them. However, it is unlikely that the experience of receiving a diagnosis was either completely positive or completely negative. In education, we know that a student’s thoughts and emotions are rarely binary, either/or situations. Students likely feel a mix of positive and negative thoughts and emotions during the diagnostic process. How they incorporate a diagnosis into their life story is unique. These messy bits are subjective truths, or the thoughts and feelings that arise as people interpret and make meaning of situations. Importantly, looking for subjective truths can help us see the contradictory and multi-faceted nature of people’s thoughts, and qualitative data allows us to avoid oversimplifying them into negative and positive feelings that could be counted, as in quantitative data. It is the role of a researcher, just like a practitioner, to seek to understand things from the perspective of the research participant (e.g. the student). Unlike with objective truth, this will not lead to a general sense of what is true for everyone, but rather what is true in a particular time and place.

Subjective truths are best expressed through qualitative data, like conversations with a student or looking at their social media posts or journal entries. As a researcher, we might invite a student to tell us how they felt after they were first diagnosed, after they spoke with family, and over the course of the therapeutic process. While it may look different from what we normally think of as science (e.g. pharmaceutical studies), these stories are indeed a rich source of data for scientific analysis. However, it is impossible to analyze what this student said without also considering the sociocultural context in which they live. For example, the concept of ADHD is generated from Western thought and philosophy. How might people from other cultures understand the issue differently?

In the DSM-5 classification of mental health disorders, there is a list of culture-bound syndromes which appear only in certain cultures. For example, brain fag syndrome (BFS) describes a unique cluster of symptoms experienced by West African students (somatic, sleep-related and cognitive complaints, difficulty in concentrating and retaining information, head and or neck pains, and eye pain). BFS involves more physical symptoms than a traditional ADHD diagnosis. Indeed, many of these syndromes do not fit within a Western conceptualization of mental health because they differentiate less between the mind and body. To a Western scientist, BFS may seem less real than ADHD. To someone from West Africa, their symptoms may not fit neatly into the ADHD framework developed in Western nations. Science has historically privileged knowledge from the United States and other nations in the West and Global North, marking them as objectively true. The objectivity of Western science as universally applicable to all cultures has been increasingly called into question as science has become less dominated by white males, and interaction between cultures and groups becomes broadly more democratic. Clearly, what is true depends in part on the context in which it is observed.

In this way, social scientists have a unique task. People are both objects and subjects. Objectively, you could quantify how tall a person is, what car they drive, how many adverse childhood experiences they had, or their score on an ADHD checklist. Subjectively, you could understand how a person has made sense of their learning and how it contributed to certain patterns in thinking, feelings, or opportunities for growth, for example. It is this added dimension that renders social science unique to natural science (like biology or physics), which focuses almost exclusively on quantitative data and objective truth. For this reason, this book is divided between projects using qualitative methods and quantitative methods.

There is no “better” or “more true” way of approaching social science. Instead, the methods a researcher chooses should match the question they ask. If you want to answer, “do vaccines cause autism?” you should choose methods appropriate to answer that question. It seeks an objective truth—one that is true for everyone, regardless of context. Studies like these use quantitative data and statistical analyses to test mathematical relationships between variables. If, on the other hand, you wanted to know “what does a diagnosis of ADHD mean to students?” you should collect qualitative data and seek subjective truths. You will gather stories and experiences from students and interpret them in a way that best represents their unique and shared truths. Where there is consensus, you will report that. Where there is contradiction, you will report that as well.

Mixed methods

In this textbook, we will treat quantitative and qualitative research methods separately. However, it is important to remember that a project can include both approaches. A mixed methods study, which we will discuss more in Chapter 8, requires thinking through a more complicated project that includes at least one quantitative component, one qualitative component, and a plan to incorporate both approaches together. As a result, mixed methods projects may require more time for conceptualization, data collection, and analysis.

Finding patterns

Regardless of whether you are seeking objective or subjective truths, research and scientific inquiry aim to find and explain patterns. Most of the time, a pattern will not explain every single person’s experience, a fact about social science that is both fascinating and frustrating. Even individuals who do not know each other can create patterns that persist over time. Those new to social science may find these patterns frustrating because they may believe that the patterns describing their sex, age, or some other facet of their lives don’t represent their experience. It’s true. A pattern can exist among your cohort without your individual participation in it. There is diversity within diversity.

Let’s consider some specific examples. You probably wouldn’t be surprised to learn that a person’s social class background has an impact on their educational attainment and achievement. You may be surprised to learn that people select romantic partners who have similar educational attainment, which in turn, impacts their children’s educational attainment (Eika, Mogstad, & Zafar, 2019).[8] People who have graduated college pair off with other college graduates, as so forth. This, in turn, reinforces existing inequalities, stratifying society by those who have the opportunity to complete college and those who don’t.

People who object to these findings tend to cite evidence from their own personal experience. However, the problem with this response is that objecting to a social pattern on the grounds that it doesn’t match one’s individual experience misses the point about patterns (think back to some of the biases introduced earlier). Patterns don’t perfectly predict what will happen to an individual person. Yet, they are a reasonable guide that, when systematically observed, can help guide education practice, thought, and action. When we don’t investigate these patterns scientifically, we are more likely to act on stereotypes, biases, and other harmful beliefs.

A final note on qualitative and quantitative methods

There is not one superior way to find patterns that help us understand the world. As we will learn about in Chapter 7, there are multiple philosophical, theoretical, and methodological ways to approach scientific truth. Qualitative methods aim to provide an in-depth understanding of a relatively small number of cases. They also provide a voice for the participants. Quantitative methods offer less depth on each case but can say more about broad patterns because they typically focus on a much larger number of cases. A researcher should approach the process of scientific inquiry by formulating a clear research question and using the methodological tools best suited to that question.

Believe it or not, there are still significant methodological battles being waged in the academic literature on objective vs. subjective social science. Usually, quantitative methods are viewed as “more scientific” and qualitative methods are viewed as “less scientific.” Part of this battle is historical. As the social sciences developed, they were compared with the natural sciences, especially physics, which rely on mathematics and statistics to come to a truth. It is a hotly debated topic whether social science should adopt the philosophical assumptions of the natural sciences—with its emphasis on prediction, mathematics, and objectivity—or use a different set of tools—contextual understanding, language, and subjectivity—to find scientific truth.

You are fortunate to be in a profession that values multiple scientific ways of knowing. The qualitative/quantitative debate is fueled by researchers who may prefer one approach over another, either because their own research questions are better suited to one particular approach or because they happened to have been trained in one specific method. In this textbook, we’ll operate from the perspective that qualitative and quantitative methods are complementary rather than competing. While these two methodological approaches certainly differ, the main point is that they simply have different goals, strengths, and weaknesses. An education researcher should select the method(s) that best match(es) the question they are asking.

Key Takeaways

- Education is informed by science.

- Education is concerned with both objective and subjective knowledge.

- Education research aims to understand patterns in the social world.

- Education researchers work within the Social Sciences and can be considered social scientists.

- Social scientists use both qualitative and quantitative methods, which, while different, are often complementary.

Exercises

-

Examine a pseudoscientific claim you’ve heard on the news or in conversation with others. Why do you consider it to be pseudoscientific? What empirical data can you find from a quick internet search that would demonstrate it lacks truth?

- Consider a topic you might want to study this semester as part of a research project. Provide a few examples of objective and subjective truths about the topic, even if you aren’t completely certain they are correct. Identify how objective and subjective truths differ.

1.3 Evidence-based practice

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Explain how educators produce and consume research as part of practice

- Review the process of evidence-based practice and how educators apply research knowledge

“Why am I in this class?”

“When will I ever use this information?”

While students aren’t always so direct, we would wager a guess that these questions are on the mind of almost every student in a research methods class. And they are valid and important questions to ask! While it may seem strange, the answer is that you will probably use these skills often. Educators engage with research on a daily basis by consuming it through popular media, education, and advanced training. They also often contribute to research projects, adding new scientific information to what we know. As professors, we also sometimes hear from field supervisors who say that research competencies are unimportant in their setting. One might wonder how these organizations measure program outcomes, report the impact of their program to board members or funding agencies, or create new interventions grounded in theory and empirical evidence.

Educators as research consumers

Whether you know it or not, your life is impacted by research every day. Many of our laws, social policies, and court proceedings are grounded in some degree of empirical research and evidence (Jenkins & Kroll-Smith, 1996).[9] That’s not to say that all laws and social policies are good or make sense. But you can’t have an informed opinion about any of them without understanding where they come from, how they were formed, and what their evidence base is. In order to be effective practitioners across micro, meso, and macro domains, educators need to understand the root causes and policy solutions to the challenges we are experiencing.

Educators might learn about research through popular media, news media websites or television programs. Social science knowledge allows educators to apply a critical eye towards new information, regardless of the source. Unfortunately, popular media does not always report on scientific findings accurately. An educator armed with scientific knowledge would be able to search for, read, and interpret the original study as well as other information that might challenge or support the study. Chapters 3, 4, and 5 of this textbook focus on information literacy, or how to understand what we already know about a topic and contribute to that body of knowledge.

When educators consume research, they are usually doing so to inform their practice. Teachers are required by their licensing board to complete continuing education classes in order to remain informed on the latest information in their field. On the macro side, analysts at public policy think tanks consume information to inform advocacy and public awareness campaigns. Regardless of the role of the educator, practice should be informed by research.

Evidence-based practice

Consuming research is the first component of evidence-based practice (EBP). Drisko and Grady (2015)[10]. EBP is at its simplest, the application of evidence within your practice. While that evidence can be a research study, it might also be data you’re collected on your students or through your own research, but applied in your practice. It is a process generally composed of “four equally weighted parts: 1) participant needs and context, (2) the best relevant research evidence, (3) participant values and preferences, and (4) expertise. It is not simply “doing what the literature says,” but is rather a process by which practitioners examine the literature, self, and context to inform interventions with students and systems (McNeese & Thyer, 2004).[11] It is a collaboration between educators, students, and context. As we discussed in section 1.2, the patterns discovered by scientific research are not applicable to all situations. Instead, we rely on our critical thinking skills to apply scientific knowledge to the real-world situations in which we live.

The bedrock of EBP is a proper assessment of the participants and systems. Once we have a solid understanding of what the issue is, we can evaluate the literature and data to determine whether there are existing interventions that have been shown to address the issue, and if so, which have been shown to be the most effective. You will learn those skills in the next few chapters. Once we know what our options are, we use our expertise and practice wisdom to make an informed decision about how to move forward.

Educators as research producers

Innovation in education is incredibly important. Educators work on wicked problems for their careers. For those of you who have practice experience, you may have had an idea of how to better approach a practice situation. That is another reason you are here in a research methods class. You (really!) will have bright ideas about what to do in practice. Sam Tsemberis relates an “Aha!” moment from his practice in this Ted talk on homelessness. While a faculty member at the New York University School of Medicine, he noticed a problem with people cycling in and out of the local psychiatric hospital wards. Clients would arrive in psychiatric crisis, stabilize under medical supervision in the hospital, and end up back at the hospital in psychiatric crisis shortly after discharge.

When he asked the clients what their issues were, they said they were unable to participate in homelessness programs because they were not always compliant with medication for their mental health diagnosis and they continued to use drugs and alcohol. The housing supports offered by the city government required abstinence and medication compliance before one was deemed “ready” for housing. For these clients, the problem was a homelessness service system that was unable to meet clients where they were—ready for housing, but not ready for abstinence and psychiatric medication. As a result, chronically homeless clients were cycling in and out of psychiatric crises, moving back and forth from the hospital to the street.

The solution that Sam Tsemberis implemented and popularized is called Housing First—an approach to homelessness prevention that starts by, you guessed it, providing people with housing first and foremost. Tsemberis’s model addresses chronic homelessness in people with co-occurring disorders (those who have a diagnosis of a substance use and mental health disorder). The Housing First model states that housing is a human right: clients should not be denied their right to housing based on substance use or mental health diagnoses.

In Housing First programs, clients are provided housing as soon as possible. The Housing First agency provides wraparound treatment from an interdisciplinary team, including social workers, nurses, psychiatrists, and former clients who are in recovery. Over the past few decades, this program has gone from a single program in New York City to the program of choice for federal, state, and local governments seeking to address homelessness in their communities.

The main idea behind Housing First is that once clients have a residence of their own, they are better able to engage in mental health and substance use treatment. While this approach may seem logical to you, it is the opposite of the traditional homelessness treatment model. The traditional approach began with the client abstaining from drug and alcohol use and taking prescribed medication. Only after clients achieved these goals were they offered group housing. If the client remained sober and medication compliant, they could then graduate towards less restrictive individual housing.

Conducting and disseminating research allows practitioners to establish an evidence base for their innovation or intervention, and to argue that it is more effective than the alternatives, and should therefore be implemented more broadly. For example, by comparing clients who were served through Housing First with those receiving traditional services, Tsemberis could establish that Housing First was more effective at keeping people housed and at addressing mental health and substance use goals. Starting first with smaller studies and graduating to larger ones, Housing First built a reputation as an effective approach to addressing homelessness. When President Bush created the Collaborative Initiative to Help End Chronic Homelessness in 2003, Housing First was used in a majority of the interventions and its effectiveness was demonstrated on a national scale. In 2007, it was acknowledged as an evidence-based practice in the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA) EBP resource center.[12]

In education

You can look around the What Works Clearinghouse for interventions on topics that interest you. Other sources of evidence-based practices include the Cochrane Reviews digital library and Campbell Collaboration. In the next few chapters, we will talk more about how to search for and locate appropriate literature. The use of systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and randomized controlled trials are particularly important in this regard, types of research we will describe more in Chapter 3 and Chapter 4.

So why share the story of Housing First? Well, we want you to think about what you hope to contribute to our knowledge of practice. What is your bright idea and how can it change the world? Practitioners innovate all the time, often incorporating those innovations into their school’s approach and mission. Using scientific research methods, teachers can demonstrate to policymakers and other educators that their innovations should be more widely used. Without this wellspring of new ideas, schools would not be able to adapt to the changing needs of their communities. Practicing educators may also participate in research projects taking place in their school or district, or run through local universities. Partnerships with educators are a common way of testing and implementing innovations in schools. In such a case, all parties receive an advantage: educators receive specialized training, students receive additional services, districts can gain prestige, and researchers can illustrate the effectiveness of an intervention.

Evidence-based practice highlights the unique perspective that teaching brings to research. Teaching both “holds” and critiques evidence. With regard to the former, “holding” evidence refers to the fact that the field of education values scientific information. The Housing First example demonstrates how this interplay between valuing and critiquing science works—first by critiquing existing research and conducting research to establish a new approach to a problem. It also demonstrates the importance of listening to your target population and privileging their understanding and perception of the issue. While their understanding is not the result of scientific inquiry, it is deeply informed through years of direct experience with the issue and embedded within the relevant cultural and historical context. Although science often searches for the “one true answer,” researchers must remain humble about the degree to which we can really know, and must begin to engage with other ways of knowing that may originate from clients and communities.

See the video on cultural humility in healthcare settings (CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0) embedded below for an example of how “one true answer” about a population can often oversimplify things and overstate how much we know about how to intervene in a given situation.

Key Takeaways

While you may not become a scientist in the sense of wearing a lab coat and using a microscope, educators must understand science in order to engage in ethical practice. In this section, we reviewed ways in which research is a part of practice, including:

- Determining the best interventions

- Ensuring existing services are accomplishing their goals

- Testing a new idea and demonstrating that it should be more widely implemented

Exercises

-

Using a teaching practice situation that you have experienced, walk through the four steps of the evidence-based practice process and how they informed your decision-making. Reflect on some of the difficulties applying EBP in the real world.

- Talk with a teacher about how they produce and consume research as part of practice. Consider asking them about the articles, books, and other scholarship that changed their practice or helped them think about a problem in a new way. You might also ask them about how they stay current with the literature as a practitioner. Reflect on your personal career goals and how research will fit into your future practice.

1.4 Education research

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Differentiate between formal and informal research roles

- Describe common barriers to engaging with education research

- Identify alternative ways of thinking about research methods

Formal and informal research roles

I’ve been teaching research methods for many years and have found that many students struggle to see the connection between research and educational practice. First of all, it’s important to mention that education researchers exist! The original authors of this textbook are researchers across university, government, and non-profit institutions. Matt and Cory are researchers at universities, and our research addresses higher education, disability policy, wellness & mental health, and intimate partner violence. Kate is a researcher at the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission in Virginia, where she studies policies related to criminal justice. Dalia, our editor, is a behavioral health researcher at RTI International, a nonprofit research institute, where she studies the opioid epidemic. The career path for social workers in formal research roles is bright and diverse, as we each bring a unique perspective with our ethical and theoretical orientation. On the Education side, Dan Laitsch is a researcher at Simon Fraser University, formerly an English teacher and a policy analyst, who has always sought out research to both inform his practice and to apply to policy analyses.

Formal research results in written products like journal articles, government reports, or policy briefs. To get a sense of formal research roles in education, consider asking a professor about their research. You can also browse around the journals in education, many listed through the Web of Science, including Open Access titles. Research resources available to SFU students through the library website. For a comprehensive list of high quality Open Access journals, check out the Directory of Open Access Journals. Additionally, the websites to most government agencies, foundations, think tanks, and advocacy groups contain formal research often conducted by educators.

But let’s be clear, studies show that most educators are not interested in becoming education researchers who publish journal articles or research reports (DeCarlo et al., 2019; Earley, 2014).[13] Once you enter post-graduate practice, you will need to apply your formal research skills to the informal research conducted by practitioners and agencies every day. Informal research can be more involved. Teachers may be surprised when they are asked to engage in research projects such as needs assessments, community scans, program and policy evaluations, and single system designs, to name a few. Macro-oriented students may have to conduct research on programs and policies as part of advocacy or administration. We cannot tell you the number former students who have contacted us looking for research resources or wanting to “pick our brains” about research they are doing as part of their employment.

Research for action

Regardless of whether educators conduct formal research that results in journal articles or informal research that is used within a school, all education research is distinctive in that it is active. We want our results to be used to effect change. Sometimes this means using findings to change how students learn. Sometimes it means using findings to show the benefits of programs or policies. Sometimes it means using findings to speak with those oppressed and marginalized persons who have been left out of the policy creation process. Additionally, it can mean using research as the mode with which to engage a constituency to address a social justice issue. All of these research activities differ; however, the one consistent ingredient is that these activities move us towards social and economic justice.

Student anxieties and beliefs about research

Unfortunately, students generally arrive in research methods classes with a mixture of dread, fear, and frustration. If you attend any given education conference, there is probably a presentation on how to better engage students in research. There is an entire body of academic research that verifies what any research professor knows to be true. Honestly, this is why the authors of this textbook started this project. We want to make research more enjoyable and engaging for students. Generally, we have found some common perceptions get in the way of students (at least) minimally enjoying research. Let’s see if any of these match with what you are thinking.

I’m never going to use this crap!

Students who tell us that research methods is not useful to them are saying something important. As a student scholar, your most valuable asset is your time. You give your time to the subjects you consider important to you and for your career. Because educators don’t become researchers or practitioner-researchers, students may feel that a research methods class is a waste of time. As faculty members, we often hear from supervisors of students in field placements that research competencies “do not apply in this setting,” which further reinforces the idea that research is an activity performed only by academic researchers.

Our discussion of evidence-based practice and the ways in which educators use research in practice brought home the idea that educators play an important role in creating and disseminating new knowledge. Furthermore, in the coming chapters, we will explore the role of research as a human right that is closely associated with the protection and establishment of other human rights. A human rights perspective also highlights the structural barriers students and practitioners face in accessing and applying scholarly knowledge in the practice arena. We hope that reframing research as something ordinary and easy to do will help address this belief that research is a useless skill.

One thing we can guarantee is that this class will be immediately useful to you. In particular, the skills you develop in finding, evaluating, and using scholarly literature will serve you throughout your graduate program and throughout your lifelong learning. In this book, you will learn how to understand and apply the scientific method to whatever topic interests you.

Research is only for super-smart people

Research methods involves a lot of terminology that may be entirely new to students. Other domains of teaching, such as practice, are easier to apply your intuition towards. You understand how to be a learner, and your experiences in life can help guide you through a practice situation or even a theoretical or conceptual question. Research may seem like a totally new area in which you have no previous experience. In research methods there can be “wrong” answers. Depending on your research question, some approaches to data analysis or measurement, for example, may not help you find the correct answer.

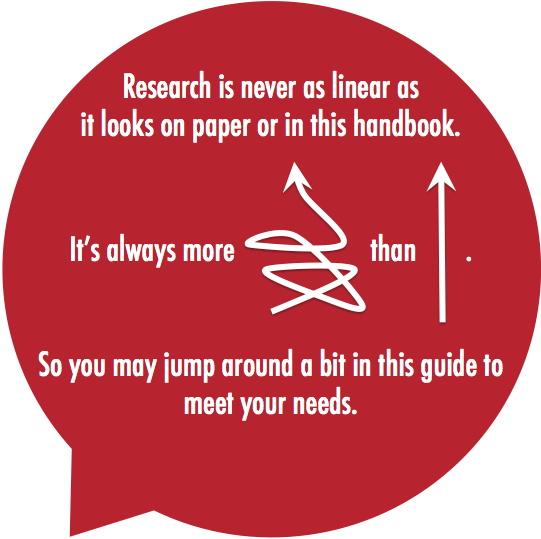

The fear is entirely understandable. Research is not straightforward. As Figure 1.1 shows, it is a process that is non-linear, involving multiple revisions, wrong turns, and dead ends before you figure out the best question and research approach. You may have to go back to chapters after having read them or even peek ahead at chapters your class hasn’t covered yet.

Moreover, research is something you learn by doing…and stumbling a few times. It’s an iterative process, or one that requires many tries to get right. There isn’t a shortcut for learning research, but if you follow along with the exercises in this book, you can break down a student research project and accomplish it piece by piece. No one just knows research. It’s something you pick up by doing it, reflecting on the experiences and results, redoing your work, and revising it in consultation with your professor and peers. Research involves exploration, risk taking, and a willingness to say, “Let’s see what we will find!”

Research is designed to suck the joy from my life

We’ve talked already about the arcane research terminology, so we won’t go into it again here. But students sometimes perceive research methods as boring. Practice knowledge and even theory are fun to learn because they are easy to apply and provide insights into the world around you. Research just seems like its own weirdly shaped and ill-fitting puzzle piece.

We completely understand where this perspective comes from and hope there are a few things you will take away from this course that aren’t boring to you. In the first section of this textbook, you will learn how to take any topic and learn what is known about it. It may seem trivial, but this is actually a superpower. Your education will teach you basic knowledge that can be applied to nearly all practice situations as well as some applied material applicable to specific practice situations. However, no education will provide you with everything you need to know. And certainly, no professor can tell you what will be discovered over the next few decades of your practice. Our work on literature reviews in the next few chapters will help you increase your skills and knowledge to become a student and practitioner. Following that, our exploration of research methods will help you understand how theories, practice models, and techniques you learn in other classes are created and tested scientifically. Eventually, you’ll see how all of the pieces fit together.

Get out of your own way

Together, these misconceptions and myths can create a self-fulfilling prophecy for students. If you believe research is boring, you won’t find it interesting. If you believe research is hard, you will struggle more with assignments. If you believe research is useless, you won’t see its utility. If you’re afraid that you will make mistakes, then you won’t want to try. While we certainly acknowledge that students aren’t going to love research as much as we do, we suggest reframing how you think about research using the following touchstones:

- All educators rely on social science research to engage in competent practice.

- No one already knows research. It’s something I’ll learn through practice. And it’s challenging for everyone, not just me.

- Research is relevant to me because it allows me to figure out what is known about any topic I want to study.

- If the topic I choose to study is important to me, I will be more interested in exploring research to help me understand it further.

Students should be intentional about managing any anxiety coming from a research project. Here are some suggestions:

- Talk to your professor if you are feeling lost. We like students!

- Talk to a librarian if you are having trouble finding information about your topic.

- Seek support from your peers or mentors.

Another way to reframe your thinking is to look at Chapter 24, which discusses how to share your research project with the world. Consider the impact you want to make with your project, who you want to share it with, and what it will mean to have answered a question you want to know about the social world. Look at the variety of professional and academic conferences in which practitioners and researchers share their knowledge. Think about where you want to go so you know how to get started.

The structure of this textbook

The textbook is divided into five parts. In the first part (Chapters 1-5), we will review how to orient your research proposal to a specific question you want to answer and review the literature to see what we know about it. Student research projects come with special limitations, as you don’t have many resources, so our chapters are designed to help you think through those limitations and think of a project that is doable. In the second part (Chapters 6-9), we will bring in theory, causality, ethics to help you conceptualize your research project and what you hope to achieve. By the end of the second part, you will create a quantitative and qualitative research question. Parts 3 and 4 will walk you through how to conduct quantitative and qualitative research, respectively. These parts run through how to recruit people to participate in your study, what to ask them, and how to interpret the results of what they say. Finally, the last part of the textbook reviews how to connect research and practice. For some, that will mean completing program evaluations as part of practice. For others, it will mean consuming research as part of continuing education as a practitioner. We hope you enjoy reading this book as much as we enjoyed writing it!

If you are still figuring out how to navigate the book using your internet browser, please go to the Downloads and Resources for Students page which contains a number of quick video tutorials. Also, the exercises in each chapter offer you an opportunity to apply what you wrote to your own research project, and the textbook is designed so that each exercise and each chapter build on one another, completing your proposal step-by-step. Of course, some exercises may be more relevant than others, but please consider completing these as you read.

Key Takeaways

- Educators engage in formal and informal research production as part of practice.

- If you feel anxious, bored, or overwhelmed by research, you are not alone!

- Becoming more familiar with research methods will help you become a better scholar and practitioner.

Exercises

- With your peers, explore your feelings towards your research methods classes. Describe some themes that come up during your conversations. Identify which issues can be addressed by your professor and which can be addressed by students.

- Browse education journals and identify an article of interest to you. Look up the author’s biography or curriculum vitae on their personal website or the website of their university.

- Cheung, J. C. S. (2016). Researching practice wisdom in social work. Journal of Social Intervention: Theory and Practice, 25(3), 24-38. ↵

- See: https://climate.nasa.gov/faq/17/do-scientists-agree-on-climate-change/ ↵

- See: http://www.igmchicago.org/surveys/import-duties ↵

- Wakefield’s article linking MMR vaccine and autism was fraudulent. British medical journal, 342, 64-66. ↵

- Mahoney, A., Karatzias, T., & Hutton, P. (2019). A systematic review and meta-analysis of group treatments for adults with symptoms associated with complex post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of affective disorders, 243, 305-321. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2017). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC ↵

- Barsky, A. (2015). DSM-5 and the ethics of diagnosis. New social worker. Retrieved from: https://www.socialworker.com/feature-articles/ethics-articles/dsm-5-and-ethics-of-diagnosis/ ↵

- Eika, L., Mogstad, M., & Zafar, B. (2019). Educational assortative mating and household income inequality. Journal of Political Economy, 127(6), 2795-2835. ↵

- Jenkins, P. J., & Kroll-Smith, S. (Eds.). (1996). Witnessing for sociology: Sociologists in court. Westport, CT: Praeger. ↵

- Drisko, J. W., & Grady, M. D. (2015). Evidence-based practice in social work: A contemporary perspective. Clinical Social Work Journal, 43(3), 274-282. ↵

- McNeece, C. A., & Thyer, B. A. (2004). Evidence-based practice and social work. Journal of evidence-based social work, 1(1), 7-25. ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2007). Pathways' housing first program. Retrieved from:https://www.samhsa.gov/homelessness-programs-resources/hpr-resources/housing-first-supports-recovery ↵

- DeCarlo, M. P., Schoppelrey, S., Crenshaw, C., Secret, M. C., & Stewart, M. (2020, January 1). Open educational resources and graduate social work students: Cost, outcomes, use, and perceptions. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/k4ytd; Earley, M. A. (2014). A synthesis of the literature on research methods education. Teaching in Higher Education, 19(3), 242-253. ↵

examining the smallest levels of interaction, usually individuals

examining interaction between groups and within communities

examining social structures and institutions

a “gut feeling” about what to do based on previous experience

“learning by doing” that guides social work intervention and increases over time

predictable flaws in thinking

observing and analyzing information in a way that agrees with what you already think is true and excludes other alternatives

a way of knowing that attempts to systematically collect and categorize facts or truths

the science of humanity, social interactions, and social structures

claims about the world that appear scientific but are incompatible with the values and practices of science

a formal process in which other esteemed researchers and experts ensure your work meets the standards and expectations of the professional field

information about the social world gathered and analyzed through scientific observation or experimentation

numerical data

data derived from analysis of texts. Usually, this is word data (like a conversation or journal entry) but can also include performances, pictures, and other means of expressing ideas.

the methods researchers use to examine empirical data

a single truth, observed without bias, that is universally applicable

one truth among many, bound within a social and cultural context

when researchers use both quantitative and qualitative methods in a project

"a set of abilities requiring individuals to 'recognize when information is needed and have the ability to locate, evaluate, and use effectively the needed information" (American Library Association, 2020)

a process composed of "four equally weighted parts: 1) current client needs and situation, (2) the best relevant research evidence, (3) client values and preferences, and (4) the clinician’s expertise" (Drisko & Grady, 2015, p. 275)

journal articles that identify, appraise, and synthesize all relevant studies on a particular topic (Uman, 2011, p.57)

a study that combines raw data from multiple quantitative studies and analyzes the pooled data using statistics

an experiment that involves random assignment to a control and experimental group to evaluate the impact of an intervention or stimulus