19

Chapter Outline

- Ethical responsibility and cultural respect (6 minute read)

- Critical considerations (6 minute read)

- Preparations: Creating a plan for qualitative data analysis (11 minute read)

- Thematic analysis (15 minute read)

- Content analysis (13 minute read)

- Grounded theory analysis (7 minute read)

- Photovoice (5 minute read)

Content warning: Examples in this chapter contain references to LGBTQ+ ageing, damaged-centered research, long-term older adult care, family violence and violence against women, vocational training, financial hardship, educational practices towards rights and justice, Schizophrenia, mental health stigma, and water rights and water access.

Just a brief disclaimer, this chapter is not intended to be a comprehensive discussion on qualitative data analysis. It does offer an overview of some of the diverse approaches that can be used for qualitative data analysis, but as you will read, even within each one of these there are variations in how they might be implemented in a given project. If you are passionate (or at least curious 😊) about conducting qualitative research, use this as a starting point to help you dive deeper into some of these strategies. Please note that there are approaches to analysis that are not addressed in this chapter, but still may be very valuable qualitative research tools. Examples include heuristic analysis,[1] narrative analysis,[2] discourse analysis,[3] and visual analysis,[4] among a host of others. These aren’t mentioned to confuse or overwhelm you, but instead to suggest that qualitative research is a broad field with many options. Before we begin reviewing some of these strategies, here a few considerations regarding ethics, cultural responsibility, power and control that should influence your thinking and planning as you map out your data analysis plan.

19.1 Ethical responsibility and cultural respectfulness

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Identify how researchers can conduct ethically responsible qualitative data analysis.

- Explain the role of culture and cultural context in qualitative data analysis (for both researcher and participant)

The ethics of deconstructing stories

Throughout this chapter, I will consistently suggest that you will be deconstructing data. That is to say, you will be taking the information that participants share with you through their words, performances, videos, documents, photos, and artwork, then breaking it up into smaller points of data, which you will then reassemble into your findings. We have an ethical responsibility to treat what is shared with a sense of respect during this process of deconstruction and reconstruction. This means that we make conscientious efforts not to twist, change, or subvert the meaning of data as we break them down or string them back together.

The act of bringing together people’s stories through qualitative research is not an easy one and shouldn’t be taken lightly. Through the informed consent process, participants should learn about the ways in which their information will be used in your research, including giving them a general idea what will happen in your analysis and what format the end results of that process will likely be.

A deep understanding of cultural context as we make sense of meaning

Similar to the ethical considerations we need to keep in mind as we deconstruct stories, we also need to work diligently to understand the cultural context in which these stories are shared. This requires that we approach the task of analysis with a sense of cultural humility, meaning that we don’t assume that our perspective or worldview as the researcher is the same as our participants. Their life experiences may be quite different from our own, and because of this, the meaning in their stories may be very different than what we might initially expect.

As such, we need to ask questions to better understand words, phrases, ideas, gestures, etc. that seem to have particular significance to participants. We also can use activities like member checking, another tool to support qualitative rigor, to ensure that our findings are accurately interpreted by vetting them with participants prior to the study conclusion. We can spend a good amount of time getting to know the groups and communities that we work with, paying attention to their values, priorities, practices, norms, strengths, and challenges. Finally, we can actively work to challenge more traditional methods research and support more participatory models that advance community co-researchers or consistent oversight of research by community advisory groups to inform, challenge, and advance this process; thus elevating the wisdom of community members and their influence (and power) in the research process.

Accounting for our influence in the analysis process

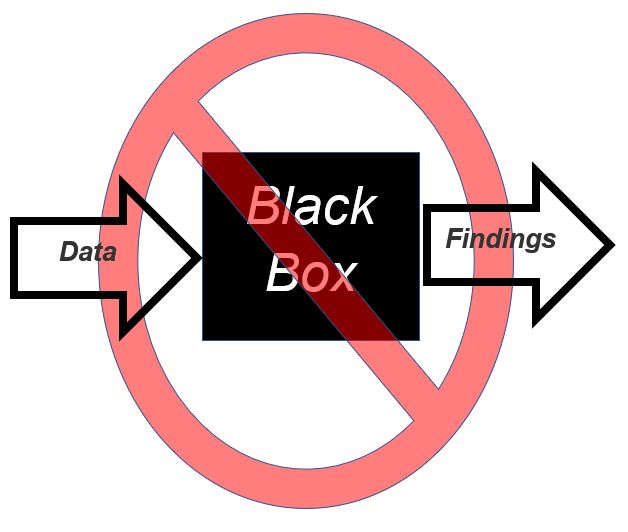

Along with our ethical responsibility to our research participants, we also have an accountability to research consumers, the scientific community at large, and other stakeholders in our qualitative research. As qualitative researchers (or quantitative researchers, for that matter), people should expect that we have attempted, to the best of our abilities, to account for our role in the research process. This is especially true in analysis. Our findings should not emerge from some ‘black box’, where raw data goes in and findings pop out the other side, with no indication of how we arrive at them. Thus, an important part of rigor is transparency and the use of tools such as writing in reflexive journals, memoing, and creating an audit trail to assist us in documenting both our thought process and activities in reaching our findings. There will be more about this in Chapter 20 dedicated to qualitative rigor.

Key Takeaways

- Ethics, as it relates specifically to the analysis phase of qualitative research, requires that we are especially thoughtful in how we treat the data that participants share with us. This data often represents very intimate parts of people’s lives and/or how they view the world. Therefore, we need to actively conduct our analysis in a way that does not misrepresent, compromise the privacy of, and/or disenfranchise or oppress our participants and the groups they belong to.

- Part of demonstrating this ethical commitment to analysis involves capturing and documenting our influence as researchers to the qualitative research process.

Exercises

After you have had a chance to read through this chapter, come back to this exercise. Think about your qualitative proposal. Based on the strategies that you might consider for analysis of your qualitative data:

19.2 Critical considerations

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Explain how data analysis may be used as tool for power and control

- Develop steps that reflect increased opportunities for empowerment of your study population, especially during the data analysis phase

How are participants present in the analysis process; What power or influence do they have

Remember, research is political. We need to consider that our findings represent ideas that are shared with us by living and breathing human beings and often the groups and communities that they represent. They have been gracious enough to share their time and their stories with us, yet they often have a limited role once we gather data from them. They are essentially putting their trust in us that we won’t be misrepresenting or culturally appropriating their stories in ways that will be harmful, damaging, or demeaning. Elliot (2016)[5] discusses the problems of "damaged-centered" research, which is research that portrays groups of people or communities as flawed, surrounded by problems, or incapable of producing change. Her work specifically references the way research and media have often portrayed people from the Appalachian region, and how these influences have perpetuated, reinforced, and even created stereotypes that these communities face. We need to thoughtfully consider how the research we are involved in will reflect on our participants and their communities.

Now, some research approaches, particularly participatory approaches, suggest that participants should be trained and actively engaged throughout the research process, helping to shape how our findings are presented and how the target population is portrayed. Implementing a participatory approach requires academic researchers to give up some of their power and control to community co-researchers. Ideally these co-researchers provide their input and are active members in determining what the findings are and interpreting why/how they are important. I believe this is a standard we need to strive for. However, this is the exception, not the rule. As such, if you are participating in a more traditional research role where community participants are not actively engaged, whenever possible, it is good practice to find ways to allow participants or other representatives to help lend their validation to our findings. While to a smaller extent, these opportunities suggest ways that community members can be empowered during the research process (and researchers can turn over some of our control). You may do this through activities like consulting with community representatives early and often during the analysis process and using transcript verification and member checking (referenced above and in our chapter on qualitative rigor) to help verify, review, and refine results. These are distinct and important roles for the community and do not mean that community members become researchers; but that they lend their perspectives in helping the researcher to interpret their findings.

The bringing together of voices: What does this represent and to whom

As education researchers, we need to be mindful that research is a tool for advancing social justice. However, that doesn’t mean that all research fulfills that capacity or that all parties perceive it in this way. Qualitative research generally involves a relatively small number of participants (or even a single person) sharing their stories. As researchers, we then bring together this data in the analysis phase in an attempt to tell a broader story about the issue we are studying. Our findings often reflect commonalities and patterns, but also should highlight contradictions, tensions, and dissension about the topic.

Exercises

Reflexive Journal Entry Prompt

Pause for a minute. Think about what the findings for your research proposal might represent.

- What do they represent to you as a researcher?

- What do they represent to participants directly involved in your study?

- What do they represent to the families of these participants?

- What do they represent to the groups and communities that represent or are connected to your population?

For each of the perspectives outlined in the reflexive journal entry prompt above, there is no single answer. As a student researcher, your study might represent a grade, an opportunity to learn more about a topic you are interested in, and a chance to hone your skills as a researcher. For participants, the findings might represent a chance to share their input or frustration that they are being misrepresented. Community members might view the research findings with skepticism that research produces any kind of change or anger that findings bring unwanted attention to the community. Obviously we can’t foretell all the answers to these questions, but thinking about them can help us to thoughtfully and carefully consider how we go about collecting, analyzing and presenting our data. We certainly need to be honest and transparent in our data analysis, but additionally, we need to consider how our analysis impacts others. It is especially important that we anticipate this and integrate it early into our efforts to educate our participants on what the research will involve, including potential risks.

It is important to note here that there are a number of perspectives that are rising to challenge traditional research methods. These challenges are often grounded in issues of power and control that we have been discussing, recognizing that research has and continues to be used as a tool for oppression and division. These perspectives include but are not limited to: Afrocentric methodologies, Decolonizing methodologies, Feminist methodologies, and Queer methodologies. While it’s a poor substitute for not diving deeper into these valuable contributions, I do want to offer a few resources if you are interested in learning more about these perspectives and how they can help to more inclusively define the research process.

Key Takeaways

- Research findings can represent many different things to many different stakeholders. Rather than as an afterthought, as qualitative researchers, we need to thoughtfully consider a range of these perspectives prior to and throughout the analysis to reduce the risk of oppression and misrepresentation through our research.

- There are a variety of strategies and whole alternative research paradigms that can aid qualitative researchers in conducting research in more empowering ways when compared to traditional research methods where the researcher largely maintain control and ownership of the research process and agenda.

Resources

This type of research means that African indigenous culture must be understood and kept at the forefront of any research and recommendations affecting indigenous communities and their culture.

Afrocentric methodologies: These methods represent research that is designed, conducted, and disseminated in ways that center and affirm African cultures, knowledge, beliefs, and values.

- Pellerin, M. (2012). Benefits of Afrocentricity in exploring social phenomena: Understanding Afrocentricity as a social science methodology.

- University of Illinois Library. (n.d.). The Afrocentric Research Center.

Decolonizing methodologies: These methods represent research that is designed, conducted, and disseminated in ways to reclaim control over indigenous ways of knowing and being.[6]

- Paris, D., & Winn, M. T. (Eds.). (2013). Humanizing research: Decolonizing qualitative inquiry with youth and communities. Sage Publications.

- Smith, L. T. (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples (2nd ed.). Zed Books Ltd.

- Pidgeon, M. & Riely, T. (2021). Understanding the Application and Use of Indigenous Research Methodologies in the Social Sciences by Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Scholars. International Journal of Education Policy & Leadership 17(8). URL: http://journals.sfu.ca/ijepl/index.php /ijepl/article/view/1065 doi:10.22230/ijepl.2021v17n8a1065

Feminist methodologies: Research methods in this tradition seek to, “remove the power imbalance between research and subject; (are) politically motivated in that (they) seeks to change social inequality; and (they) begin with the standpoints and experiences of women”.[7]

- Gill, J. (n.d.) Feminist research methodologies. Feminist Perspectives on Media and Technology.

- U.C.Davis., Feminist Research Institute. (n.d.). What is feminist research?

Queer(ing) methodologies: Research methods using this approach aim to question, challenge and often reject knowledge that is commonly accepted and privileged in society and elevate and empower knowledge and perspectives that are often perceived as non-normative.

- de Jong, D. H. (2014). A new paradigm in social work research: It’s here, it’s queer, get used to it!.

- Ghaziani, A., & Brim, M. (Eds.). (2019). Imagining queer methods. NYU Press.

19.3 Preparations: Creating a plan for qualitative data analysis

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Identify how your research question, research aim, sample selection, and type of data may influence your choice of analytic methods

- Outline the steps you will take in preparation for conducting qualitative data analysis in your proposal

Now we can turn our attention to planning your analysis. The analysis should be anchored in the purpose of your study. Qualitative research can serve a range of purposes. Below is a brief list of general purposes we might consider when using a qualitative approach.

- Are you trying to understand how a particular group is affected by an issue?

- Are you trying to uncover how people arrive at a decision in a given situation?

- Are you trying to examine different points of view on the impact of a recent event?

- Are you trying to summarize how people understand or make sense of a condition?

- Are you trying to describe the needs of your target population?

If you don’t see the general aim of your research question reflected in one of these areas, don’t fret! This is only a small sampling of what you might be trying to accomplish with your qualitative study. Whatever your aim, you need to have a plan for what you will do once you have collected your data.

Exercises

Decision Point: What are you trying to accomplish with your data?

- Consider your research question. What do you need to do with the qualitative data you are gathering to help answer that question?

To help answer this question, consider:

-

- What action verb(s) can be associated with your project and the qualitative data you are collecting? Does your research aim to summarize, compare, describe, examine, outline, identify, review, compose, develop, illustrate, etc.?

- Then, consider noun(s) you need to pair with your verb(s)—perceptions, experiences, thoughts, reactions, descriptions, understanding, processes, feelings, actions responses, etc.

Iterative or linear

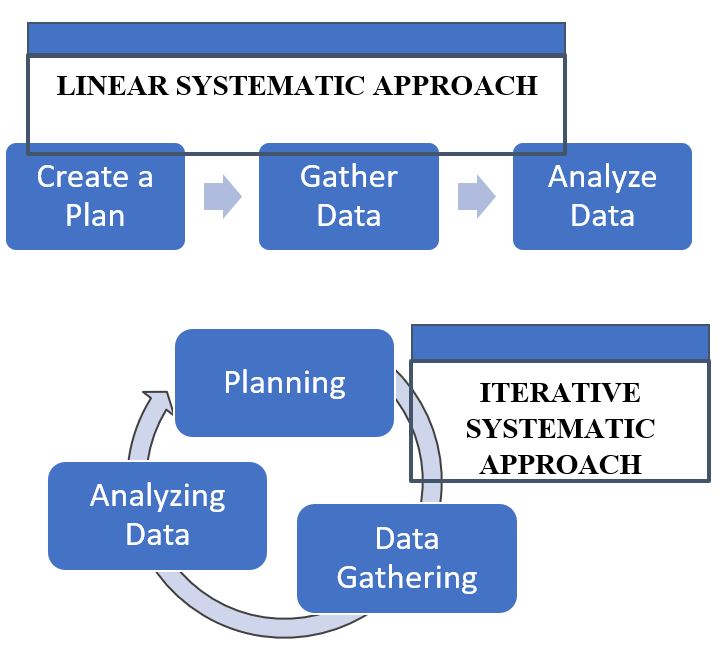

We touched on this briefly in Chapter 17 about qualitative sampling, but this is an important distinction to consider. Some qualitative research is linear, meaning it follows more of a traditionally quantitative process: create a plan, gather data, and analyze data; each step is completed before we proceed to the next. You can think of this like how information is presented in this book. We discuss each topic, one after another.

However, many times qualitative research is iterative, or evolving in cycles. An iterative approach means that once we begin collecting data, we also begin analyzing data as it is coming in. This early and ongoing analysis of our (incomplete) data then impacts our continued planning, data gathering and future analysis. Again, coming back to this book, while it may be written linear, we hope that you engage with it iteratively as you are building your proposal. By this we mean that you will revisit previous sections so you can understand how they fit together and you are in continuous process of building and revising how you think about the concepts you are learning about.

As you may have guessed, there are benefits and challenges to both linear and iterative approaches. A linear approach is much more straightforward, each step being fairly defined. However, linear research being more defined and rigid also presents certain challenges. A linear approach assumes that we know what we need to ask or look for at the very beginning of data collection, which often is not the case.

With iterative research, we have more flexibility to adapt our approach as we learn new things. We still need to keep our approach systematic and organized, however, so that our work doesn’t become a free-for-all. As we adapt, we do not want to stray too far from the original premise of our study. It’s also important to remember with an iterative approach that we may risk ethical concerns if our work extends beyond the original boundaries of our informed consent and IRB agreement. If you feel that you do need to modify your original research plan in a significant way as you learn more about the topic, you can submit an addendum to modify your original application that was submitted. Make sure to keep detailed notes of the decisions that you are making and what is informing these choices. This helps to support transparency and your credibility throughout the research process.

Exercises

Decision Point: Will your analysis reflect more of a linear or an iterative approach?

- What justifies or supports this decision?

Think about:

- Fit with your research question

- Available time and resources

- Your knowledge and understanding of the research process

Exercises

Reflexive Journal Entry Prompt

- Are you more of a linear thinker or an iterative thinker?

- What evidence are you basing this on?

- How might this help or hinder your qualitative research process?

- How might this help or hinder you in a practice setting as you work with clients?

Inductive or deductive?

Ask your self what you “know” about your topic. Do you have idea about what you might uncover, based on your previous reading of the literature? Or are you starting at a very basic level, unsure of what you will find? We talked before about inductive and deductive research approaches, and it’s useful to revisit this as you build your qualitative study.

If you have a fairly good idea of the things that will come up in your research, and there are specific questions you know you’ll want to ask, you’ll be taking a deductive approach and working with a priori themes. As you put together your data gathering plan, you’ll want to make sure there are clear and well-defined linkages between the literature, the a priori themes you’ll be exploring, and the questions you’ll be asking of participants.

On the other hand, if you find that there isn’t a lot of knowledge about the issues that concern you, and instead, you really want to see what ideas and issues flow from participants, you’ll be taking a more inductive approach. In this case your questions will be more general, allowing participants a great deal of agency in responding. As you’ll learn later, you’ll be making meaning from the data you collect, rather than seeking out information about pre-existing (a priori) themes.

In truth, qualitative research often takes both of these approaches, but you’ll want to be intentional as you plan your data analysis and collection plans.

Acquainting yourself with your data

As you begin your analysis, you need to get to know your data. This usually means reading through your data prior to any attempt at breaking it apart and labeling it. You might read through a couple of times, in fact. This helps give you a more comprehensive feel for each piece of data and the data as a whole, again, before you start to break it down into smaller units or deconstruct it. This is especially important if others assisted us in the data collection process. We often gather data as part of team and everyone involved in the analysis needs to be very familiar with all of the data.

Capturing your reaction to the data

During the review process, our understanding of the data often evolves as we observe patterns and trends. It is a good practice to document your reaction and evolving understanding. Your reaction can include noting phrases or ideas that surprise you, similarities or distinct differences in responses, additional questions that the data brings to mind, among other things. We often record these reactions directly in the text or artifact if we have the ability to do so, such as making a comment in a word document associated with a highlighted phrase. If this isn’t possible, you will want to have a way to track what specific spot(s) in your data your reactions are referring to. In qualitative research we refer to this process as memoing. Memoing is a strategy that helps us to link our findings to our raw data, demonstrating transparency. If you are using a Computre-Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software (CAQDAS) software package, memoing functions are generally built into the technology.

Capturing your emerging understanding of the data

During your reviewing and memoing you will start to develop and evolve your understanding of what the data means. This understanding should be dynamic and flexible, but you want to have a way to capture this understanding as it evolves. You may include this as part of your memoing or as part of your codebook where you are tracking the main ideas that are emerging and what they mean. Figure 19.3 is an example of how your thinking might change about a code and how you can go about capturing it. Coding is a part of the qualitative data analysis process where we begin to interpret and assign meaning to the data. It represents one of the first steps as we begin to filter the data through our own subjective lens as the researcher. We will discuss coding in much more detail in the sections below covering various different approaches to analysis.

| Date | Code Lable | Explanations |

| 6/18/18 | Experience of wellness | This code captures the different ways people describe wellness in their lives |

| 6/22/18 | Understanding of wellness | Changed the label of this code slightly to reflect that many participants emphasize the cognitive aspect of how they understand wellness—how they think about it in their lives, not only the act of ‘experiencing it’. This understanding seems like a precursor to experiencing. An evolving sense of how you think about wellness in your life. |

| 6/25/18 | Wellness experienced by developing personal awareness | A broader understanding of this category is developing. It involves building a personalized understanding of what makes up wellness in each person’s life and the role that they play in maintaining it. Participants have emphasized that this is a dynamic, personal and onging process of uncovering their own intimate understanding of wellness. They describe having to experiment, explore, and reflect to develop this awareness. |

Exercises

Decision Point: How to capture your thoughts?

- How will you capture your thinking about the data and your emerging understanding about what it means?

- What will this look like?

- How often will you do it?

- How will you keep it organized and consistent over time?

In addition, you will want to be actively using your reflexive journal during this time. Document your thoughts and feelings throughout the research process. This will promote transparency and help account for your role in the analysis.

For entries during your analysis, respond to questions such as these in your journal:

- What surprises you about what participants are sharing?

- How has this information challenged you to look at this topic differently?

- As you reflect on these findings, what personal biases or preconceived notions have been exposed for you?

- Where might these have come from?

- How might these be influencing your study?

- How will you proceed differently based on what you are learning?

By including community members as active co-researchers, they can be invaluable in reviewing, reacting to and leading the interpretation of data during your analysis. While it can certainly be challenging to converge on an agreed-upon version of the results; their insider knowledge and lived experience can provide very important insights into the data analysis process.

Determining when you are finished

When conducting quantitative research, it is perhaps easier to decide when we are finished with our analysis. We determine the tests we need to run, we perform them, we interpret them, and for the most part, we call it a day. It’s a bit more nebulous for qualitative research. There is no hard and fast rule for when we have completed our qualitative analysis. Rather, our decision to end the analysis should be guided by reflection and consideration of a number of important questions. These questions are presented below to help ensure that your analysis results in a finished product that is comprehensive, systematic, and coherent.

Have I answered my research question?

Your analysis should be clearly connected to and in service of answering your research question. Your examination of the data should help you arrive at findings that sufficiently address the question that you set out to answer. You might find that it is surprisingly easy to get distracted while reviewing all your data. Make sure as you conducted the analysis you keep coming back to your research question.

Have I utilized all my data?

Unless you have intentionally made the decision that certain portions of your data are not relevant for your study, make sure that you don’t have sources or segments of data that aren’t incorporated into your analysis. Just because some data doesn’t “fit” the general trends you are uncovering, find a way to acknowledge this in your findings as well so that these voices don’t get lost in your data.

Have I fulfilled my obligation to my participants?

As a qualitative researcher, you are a craftsperson. You are taking raw materials (e.g. people’s words, observations, photos) and bringing them together to form a new creation, your findings. These findings need to both honor the original integrity of the data that is shared with you, but also help tell a broader story that answers your research question(s).

Have I fulfilled my obligation to my audience?

Not only do your findings need to help answer your research question, but they need to do so in a way that is consumable for your audience. From an analysis standpoint, this means that we need to make sufficient efforts to condense our data. For example, if you are conducting a thematic analysis, you don’t want to wind up with 20 themes. Having this many themes suggests that you aren’t finished looking at how these ideas relate to each other and might be combined into broader themes. Having these sufficiently reduced to a handful of themes will help tell a more complete story, one that is also much more approachable and meaningful for your reader.

In the following subsections, there is information regarding a variety of different approaches to qualitative analysis. In designing your qualitative study, you would identify an analytical approach as you plan out your project. The one you select would depend on the type of data you have and what you want to accomplish with it.

Key Takeaways

- Qualitative research analysis requires preparation and careful planning. You will need to take time to familiarize yourself with the data in general sense before you begin analyzing.

- Once you begin your analysis, make sure that you have strategies for capture and recording both your reaction to the data and your corresponding developing understanding of what the collective meaning of the data is (your results). Qualitative research is not only invested in the end results but also the process at which you arrive at them.

Exercises

Decision Point: When will you stop?

- How will you know when you are finished? What will determine your endpoint?

- How will you monitor your work so you know when it’s over?

19.4 Thematic analysis

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Explain defining features of thematic analysis as a strategy for qualitative data analysis and identify when it is most effectively used

- Formulate an initial thematic analysis plan (if appropriate for your research proposal)

What are you trying to accomplish with thematic analysis?

As its name suggests, with thematic analysis we are attempting to identify themes or common ideas across our data. Themes can help us to:

- Determine shared meaning or significance of an event

- Povide a more complete understanding of concept or idea by exposing different dimensions of the topic

- Explore a range of values, beliefs or perceptions on a given topic

Themes help us to identify common ways that people are making sense of their world. Let’s say that you are studying empowerment of teens living at home by interviewing them. As you review your transcripts, you note that a number of participants are talking about the importance of maintaining connection to friends (e.g. from school, churches, sporting teams, or other community connections) and having input into how they allocate their free time (e.g. studying, socializing, exercising, spending time with family). You might note that these are two emerging themes in your data. After you have deconstructed your data, you will likely end up with a handful (likely three or four) central ideas or take-aways that become the themes or major findings of your research.

Variations in approaches to thematic analysis

There are a variety of ways to approach qualitative data analysis, but even within the broad approach of thematic analysis, there is variation. Some thematic analysis takes on an inductive analysis approach. In this case, we would first deconstruct our data into small segments representing distinct ideas (this is explained further in the section below on coding data). We then go on to see which of these pieces seem to group together around common ideas.

In direct contrast, you might take a deductive analysis approach (like we discussed in Chapter 8), in which you start with some idea about what grouping might look like and we see how well our data fits into those pre-identified groupings. These initial deductive groupings (we call these a priori categories) often come from an existing theory related to the topic we are studying. You may also elect to use a combination of deductive and inductive strategies, especially if you find that much of your data is not fitting into deductive categories and you decide to let new categories inductively emerge.

A couple things to note here. If you are using a deductive approach, be clear in specifying where your a priori categories came from. For instance, perhaps you are interested in studying the conceptualization of social work in other cultures. You begin your analysis with prior research conducted by Tracie Mafile’o (2004) that identified the concepts of fekau’aki (connecting) and fakatokilalo (humility) as being central to Tongan social work practice.[8] You decide to use these two concepts as part of your initial deductive framework, because you are interested in studying a population that shares much in common with the Tongan people. When using an inductive approach, you need to plan to use memoing and reflexive journaling to document where the new categories or themes are coming from.

Coding data

Coding is the process of breaking down your data into smaller meaningful units. Just like any story is made up by the bringing together of many smaller ideas, you need to uncover and label these smaller ideas within each piece of your data. After you have reviewed each piece of data you will go back and assign labels to words, phrases, or pieces of data that represent separate ideas that can stand on their own. Identifying and labeling codes can be tricky. When attempting to locate units of data to code, look for pieces of data that seem to represent an idea in-and-of-itself; a unique thought that stands alone. For additional information about coding, check out this brief video from Duke’s Social Science Research Institute on this topic. It offers a nice concise overview of coding and also ties into our previous discussion of memoing to help encourage rigor in your analysis process.

As suggested in the video[9], when you identify segments of data and are considering what to label them ask yourself:

- How does this relate to/help to answer my research question?

- How does this connect with what we know from the existing literature?

- How does this fit (or contrast) with the rest of my data?

You might do the work of coding in the margins if you are working with hard copies, or you might do this through the use of comments or through copying and pasting if you are working with digital materials (like pasting them into an excel sheet, as in the example below). If you are using a CAQDAS, there will be a function(s) built into the software to accomplish this.

Regardless of which strategy you use, the central task of thematic analysis is to have a way to label discrete segments of your data with a short phrase that reflects what it stands for. As you come across segments that seem to mean the same thing, you will want to use the same code. Make sure to select the words to represent your codes wisely, so that they are clear and memorable. When you are finished, you will likely have hundreds (if not thousands!) of different codes – again, a story is made up of many different ideas and you are bringing together many different stories! A cautionary note, if you are physically manipulating your data in some way, for example copying and pasting, which I frequently do, you need to have a way to trace each code or little segment back to its original home (the artifact that it came from).

When I’m working with interview data, I will assign each interview transcript a code and use continuous line numbering. That way I can label each segment of data or code with a corresponding transcript code and line number so I can find where it came from in case I need to refer back to the original.

The following is an excerpt from a portion of an autobiographical memoir (Wolf, 2010)[10]. Continuous numbers have been added to the transcript to identify line numbers (Figure 19.4). A few preliminary codes have been identified from this data and entered into a data matrix (below) with information to trace back to the raw data (transcript) (Figure 19.5).

| 1 | I have a vivid picture in my mind of my mother, sitting at a kitchen table, |

| 2 | listening to the announcement of FDR’s Declaration of War in his famous “date |

| 3 | which will live in infamy” speech delivered to Congress on December 8, 1941: |

| 4 | “The United States was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces |

| 5 | of the Empire of Japan.” I still can hear his voice. |

| 6 | |

| 7 | I couldn’t understand “war,” of course, but I knew that something terrible had |

| 8 | happened; and I wanted it to stop so my mother wouldn’t be unhappy. I later |

| 9 | asked my older brother what war was and when it would be over. He said, “Not |

| 10 | soon, so we better get ready for it, and, remember, kid, I’m a Captain and you’re a |

| 11 | private.” |

| 12 | |

| 13 | So the war became a family matter in some sense: my mother’s sorrow (thinking, |

| 14 | doubtless, about the fate and future of her sons) and my brother’s assertion of |

| 15 | male authority and superiority always thereafter would come to mind in times of |

| 16 | international conflict—just as Pearl Harbor, though it was far from the mainland, |

| 17 | always would be there for America as an icon of victimization, never more so than |

| 18 | in the semi-paranoid aftermath of “9/11” with its disastrous consequences in |

| 19 | Iraq. History always has a personal dimension. |

| Data Segment | Transcript (Source) | Transcript Line | Initial Code |

| I have a vivid picture in my mind of my mother, sitting at a kitchen table, listening to the announcement of FDR’s Declaration of War in his famous “date which will live in infamy” speech delivered to Congress on December 8, 1941: “The United States was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan.” I still can hear his voice. | Wolf Memoir | 1-5 | Memories |

| I couldn’t understand “war,” of course, but I knew that something terrible had happened; and I wanted it to stop so my mother wouldn’t be unhappy. | Wolf Memoir | 7-8 | Meaning of War |

| I later asked my older brother what war was and when it would be over. He said, “Not soon, so we better get ready for it, and, remember, kid, I’m a Captain and you’re a private.” | Wolf Memoir | 8-11 | Meaning of War; Memories |

Exercises

Below is another excerpt from the same memoir[11]

What segments of this interview can you pull out and what initial code would you place on them?

Create a data matrix as you reflect on this.

It was painful to think, even at an early age, that a part of the world I was beginning to love—Europe—was being substantially destroyed by the war; that cities with their treasures, to say nothing of innocent people, were being bombed and consumed in flames. I was a patriotic young American and wanted “us” to win the war, but I also wanted Europe to be saved.

Some displaced people began to arrive in our apartment house, and even as I knew that they had suffered in Europe, their names and language pointed back to a civilized Europe that I wanted to experience. One person, who had studied at Heidelberg, told me stories about student life in the early part of the 20th century that inspired me to want to become an accomplished student, if not a “student prince.” He even had a dueling scar. A baby-sitter showed me a photo of herself in a feathered hat, standing on a train platform in Bratislava. I knew that she belonged in a world that was disappearing.

For those of us growing up in New York City in the 1940s, Japan, following Pearl Harbor and the “death march” in Corregidor, seemed to be our most hated enemy. The Japanese were portrayed as grotesque and blood-thirsty on posters. My friends and I were fighting back against the “Japs” in movie after movie: Gung Ho, Back to Bataan, The Purple Heart, Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, They Were Expendable, and Flying Tigers, to name a few.

We wanted to be like John Wayne when we grew up. It was only a few decades after the war, when we realized the horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, that some of us began to understand that the Japanese, whatever else was true, had been dehumanized as a people; that we had annihilated, guiltlessly at the time, hundreds of thousands of non-combatants in a horrific flash. It was only after the publication of John Hersey’s Hiroshima(1946), that we began to think about other sides of the war that patriotic propaganda had concealed.

When my friends and I went to summer camp in the foothills of the Berkshires during the late years of the war and sang patriotic songs around blazing bonfires, we weren’t thinking about the firestorms of Europe (Dresden) and Japan. We were worried that our counselors would be drafted and suddenly disappear, leaving us unprotected.

Identifying, reviewing, and refining themes

Now we have our codes, we need to find a sensible way of putting them together. Remember, we want to narrow this vast field of hundreds of codes down to a small handful of themes. If we don’t review and refine all these codes, the story we are trying to tell with our data becomes distracting and diffuse. An example is provided below to demonstrate this process.

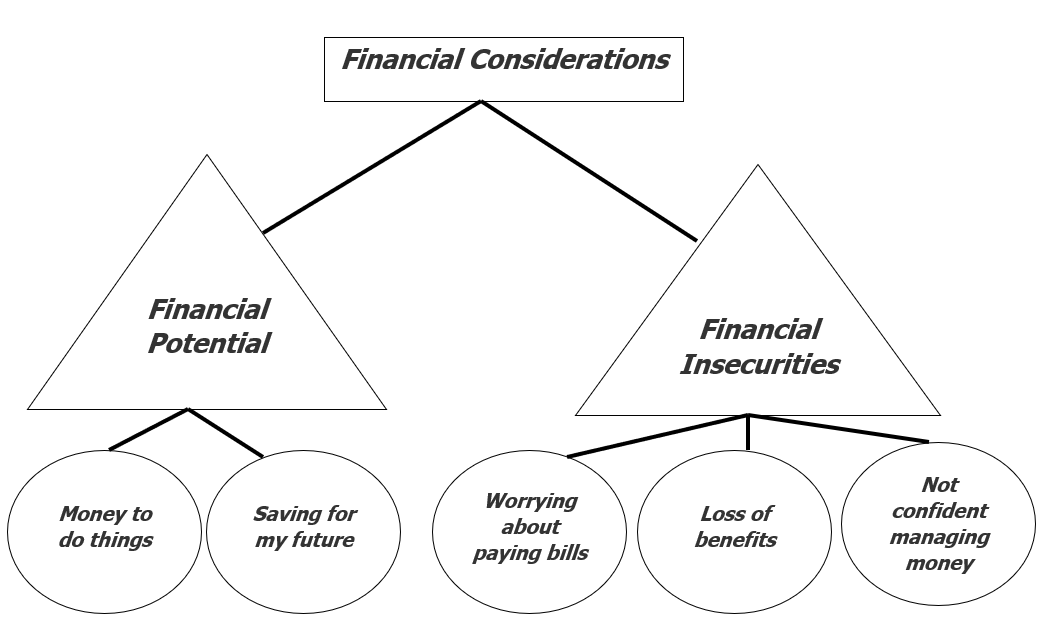

As we refine our thematic analysis, our first step will be to identify groups of codes that hang together or seem to be related. Let’s say you are studying the experience of people who are in a vocational preparation program and you have codes labeled “worrying about paying the bills” and “loss of benefits”. You might group these codes into a category you label “income & expenses” (Figrue 19.6).

| Code | Category | Reasoning |

| Worrying about paying the bills | Income & expenses | Seem to be talking about financial stressors and potential impact on resources |

| Loss of benefits |

| Code | Category | Reasoning | Category | Reasoning |

| Worrying about Paying the bills | Income & expenses | Seem to be talking about financial stressors and potential impact on resources | Financial insecurities | Expanded category to also encompass personal factor- confidence related to issue |

| Loss of benefits | ||||

| Not confident managing money |

You may review and refine the groups of your codes many times during the course of your analysis, including shifting codes around from one grouping to another as you get a clearer picture of what each of the groups represent. This reflects the iterative process we were describing earlier. While you are shifting codes and relabeling categories, track this! A research journal is a good place to do this. So, as in the example above, you would have a journal entry that explains that you changed the label on the category from “income & expenses” to “financial insecurities” and you would briefly explain why. Your research journal can take many different forms. It can be hard copy, an evolving word document, or a spreadsheet with multiple tabs (Figure 19.8).

| Journal Entry Date: 10/04/19 Changed category [Income & expenses] to [Financial insecurities] to include new code “Not confident managing money” that appears to reflect a personal factor related to the participant’s confidence or personal capability related to the topic. |

Now, eventually you may decide that some of these categories can also be grouped together, but still stand alone as separate ideas. Continuing with our example above, you have another category labeled “financial potential” that contains codes like “money to do things” and “saving for my future”. You determine that “financial insecurities” and “financial potential” are related, but distinctly different aspects of a broader grouping, which you go on to label “financial considerations”. This broader grouping reflects both the more worrisome or stressful aspects of people’s experiences that you have interviewed, but also the optimism and hope that was reflected related to finances and future work (Figure 19.9).

| Code | Category | Reasoning | Category | Reasoning | Theme |

| Worrying about paying the bills | Income & expenses | Seem to be talking about financial stressors and potential impact on resources | Financial insecurities | Expanded category to also encompass personal factor- confidence related to issue | Financial considerations |

| Loss of benefits | |||||

| Not confident managing money | |||||

| Money to do things | Financial potential | Reflects positive aspects related to earnings | |||

| Saving for my future |

This broadest grouping then becomes your theme and utilizing the categories and the codes contained therein, you create a description of what each of your themes means based on the data you have collected, and again, can record this in your research journal entry (Figure 19.10).

| Journal Entry Date: 10/10/19 Identified an emerging theme [Financial considerations] that reflects both the concerns reflected under [Financial insecurities] but also the hopes or more positive sentiments related to finances and work [Financial potential] expressed by participants. As participants prepare to return to work, they appear to experience complex and maybe even conflicting feelings towards how it will impact their finances and what this will mean for their lives. |

Building a thematic representation

However, providing a list of themes may not really tell the whole story of your study. It may fail to explain to your audience how these individual themes relate to each other. A thematic map or thematic array can do just that: provides a visual representation of how each individual category fits with the others. As you build your thematic representation, be thoughtful of how you position each of your themes, as this spatially tells part of the story.[12] You should also make sure that the relationships between the themes represented in your thematic map or array are narratively explained in your text as well.

Figure 19.11 offers an illustration of the beginning of thematic map for the theme we had been developing in the examples above. I emphasize that this is the beginning because we would likely have a few other themes (not just “financial considerations”). These other themes might have codes or categories in common with this theme, and these connections would be visual evident in our map. As you can see in the example, the thematic map allows the reader, reviewer, or researcher can quickly see how these ideas relate to each other. Each of these themes would be explained in greater detail in our write up of the results. Additionally, sample quotes from the data that reflected those themes are often included.

Key Takeaways

- Thematic analysis offers qualitative researchers a method of data analysis through which we can identify common themes or broader ideas that are represented in our qualitative data.

- Themes are identified through an iterative process of coding and categorizing (or grouping) to identify trends during your analysis.

- Tracking and documenting this process of theme identification is an important part of utilizing this approach.

Resources

References for learning more about Thematic Analysis

Clarke, V. (2017, December 9). What is thematic analysis?

Maguire, M., & Delahunt, B. (2017). Doing a thematic analysis: A practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars.

Nowell et al. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria.

The University of Auckland. (n.d.). Thematic analysis: A reflexive approach.

A few exemplars of studies employing Thematic Analysis

Bastiaensens et al. (2019). “Were you cyberbullied? Let me help you.” Studying adolescents’ online peer support of cyberbullying victims using thematic analysis of online support group Fora.

Borgström, Å., Daneback, K., & Molin, M. (2019). Young people with intellectual disabilities and social media: A literature review and thematic analysis.

Kapoulitsas, M., & Corcoran, T. (2015). Compassion fatigue and resilience: A qualitative analysis of social work practice.

19.5 Content analysis

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Explain defining features of content analysis as a strategy for analyzing qualitative data

- Determine when content analysis can be most effectively used

- Formulate an initial content analysis plan (if appropriate for your research proposal)

What are you trying to accomplish with content analysis

Much like with thematic analysis, if you elect to use content analysis to analyze your qualitative data, you will be deconstructing the artifacts that you have sampled and looking for similarities across these deconstructed parts. Also consistent with thematic analysis, you will be seeking to bring together these similarities in the discussion of your findings to tell a collective story of what you learned across your data. While the distinction between thematic analysis and content analysis is somewhat murky, if you are looking to distinguish between the two, content analysis:

- Places greater emphasis on determining the unit of analysis. Just to quickly distinguish, when we discussed sampling in Chapter 10 we also used the term “unit of analysis. As a reminder, when we are talking about sampling, unit of analysis refers to the entity that a researcher wants to say something about at the end of her study (individual, group, or organization). However, for our purposes when we are conducting a content analysis, this term has to do with the ‘chunk’ or segment of data you will be looking at to reflect a particular idea. This may be a line, a paragraph, a section, an image or section of an image, a scene, etc., depending on the type of artifact you are dealing with and the level at which you want to subdivide this artifact.

- Content analysis is also more adept at bringing together a variety of forms of artifacts in the same study. While other approaches can certainly accomplish this, content analysis more readily allows the researcher to deconstruct, label and compare different kinds of ‘content’. For example, perhaps you have developed a new advocacy training for community members. To evaluate your training you want to analyze a variety of products they create after the workshop, including written products (e.g. letters to their representatives, community newsletters), audio/visual products (e.g. interviews with leaders, photos hosted in a local art exhibit on the topic) and performance products (e.g. hosting town hall meetings, facilitating rallies). Content analysis can allow you the capacity to examine evidence across these different formats.

For some more in-depth discussion comparing these two approaches, including more philosophical differences between the two, check out this article by Vaismoradi, Turunen, and Bondas (2013).[13]

Variations in the approach

There are also significant variations among different content analysis approaches. Some of these approaches are more concerned with quantifying (counting) how many times a code representing a specific concept or idea appears. These are more quantitative and deductive in nature. Other approaches look for codes to emerge from the data to help describe some idea or event. These are more qualitative and inductive. Hsieh and Shannon (2005)[14] describe three approaches to help understand some of these differences:

- Conventional Content Analysis. Starting with a general idea or phenomenon you want to explore (for which there is limited data), coding categories then emerge from the raw data. These coding categories help us understand the different dimensions, patterns, and trends that may exist within the raw data collected in our research.

- Directed Content Analysis. Starts with a theory or existing research for which you develop your initial codes (there is some existing research, but incomplete in some aspects) and uses these to guide your initial analysis of the raw data to flesh out a more detailed understanding of the codes and ultimately, the focus of your study.

- Summative Content Analysis. Starts by examining how many times and where codes are showing up in your data, but then looks to develop an understanding or an “interpretation of the underlying context” (p.1277) for how they are being used. As you might have guessed, this approach is more likely to be used if you’re studying a topic that already has some existing research that forms a basic place to begin the analysis.

This is only one system of categorization for different approaches to content analysis. If you are interested in utilizing a content analysis for your proposal, you will want to design an approach that fits well with the aim of your research and will help you generate findings that will help to answer your research question(s). Make sure to keep this as your north star, guiding all aspects of your design.

Determining your codes

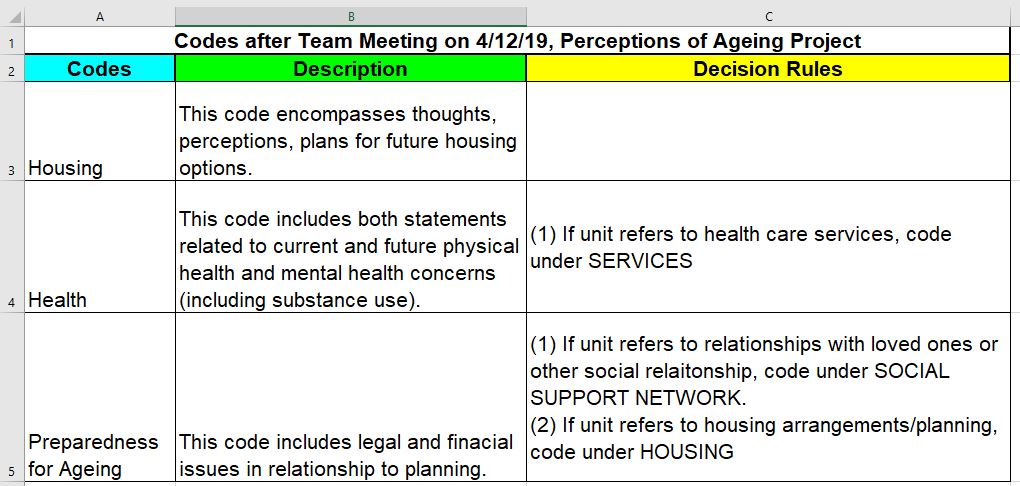

We are back to coding! As in thematic analysis, you will be coding your data (labeling smaller chunks of information within each data artifact of your sample). In content analysis, you may be using pre-determined codes, such as those suggested by an existing theory (deductive) or you may seek out emergent codes that you uncover as you begin reviewing your data (inductive). Regardless of which approach you take, you will want to develop a well-documented codebook.

A codebook is a document that outlines the list of codes you are using as you analyze your data, a descriptive definition of each of these codes, and any decision-rules that apply to your codes. A decision-rule provides information on how the researcher determines what code should be placed on an item, especially when codes may be similar in nature. If you are using a deductive approach, your codebook will largely be formed prior to analysis, whereas if you use an inductive approach, your codebook will be built over time. To help illustrate what this might look like, Figure 19.12 offers a brief excerpt of a codebook from one of the projects I’m currently working on.

Coding, comparing, counting

Once you have (or are developing) your codes, your next step will be to actually code your data. In most cases, you are looking for your coding structure (your list of codes) to have good coverage. This means that most of the content in your sample should have a code applied to it. If there are large segments of your data that are uncoded, you are potentially missing things. Now, do note that I said most of the time. There are instances when we are using artifacts that may contain a lot of information, only some of which will apply to what we are studying. In these instances, we obviously wouldn’t be expecting the same level of coverage with our codes. As you go about coding you may change, refine and adapt your codebook as you go through your data and compare the information that reflects each code. As you do this, keep your research journal handy and make sure to capture and record these changes so that you have a trail documenting the evolution of your analysis. Also, as suggested earlier, content analysis may also involve some degree of counting as well. You may be keeping a tally of how many times a particular code is represented in your data, thereby offering your reader both a quantification of how many times (and across how many sources) a code was reflected and a narrative description of what that code came to mean.

Representing the findings from your coding scheme

Finally, you need to consider how you will represent the findings from your coding work. This may involve listing out narrative descriptions of codes, visual representations of what each code came to mean or how they related to each other, or a table that includes examples of how your data reflected different elements of your coding structure. However you choose to represent the findings of your content analysis, make sure the resulting product answers your research question and is readily understandable and easy-to-interpret for your audience.

Key Takeaways

- Much like thematic analysis, content analysis is concerned with breaking up qualitative data so that you can compare and contrast ideas as you look across all your data, collectively. A couple of distinctions between thematic and content analysis include content analysis’s emphasis on more clearly specifying the unit of analysis used for the purpose of analysis and the flexibility that content analysis offers in comparing across different types of data.

- Coding involves both grouping data (after it has been deconstructed) and defining these codes (giving them meaning). If we are using a deductive approach to analysis, we will start with the code defined. If we are using an inductive approach, the code will not be defined until the end of the analysis.

Exercises

Identify a qualitative research article that uses content analysis (do a quick search of “qualitative” and “content analysis” in your research search engine of choice).

- How do the authors display their findings?

- What was effective in their presentation?

- What was ineffective in their presentation?

Resources

Resources for learning more about Content Analysis

Bengtsson, M. (2016). How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis.

Colorado State University (n.d.) Writing@CSU Guide: Content analysis.

Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, Population Health. (n.d.) Methods: Content analysis

Mayring, P. (2000, June). Qualitative content analysis.

A few exemplars of studies employing Content Analysis

Collins et al. (2018). Content analysis of advantages and disadvantages of drinking among individuals with the lived experience of homelessness and alcohol use disorders.

Corley, N. A., & Young, S. M. (2018). Is social work still racist? A content analysis of recent literature.

Deepak et al. (2016). Intersections between technology, engaged learning, and social capital in social work education.

19.6 Grounded theory analysis

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Explain defining features of grounded theory analysis as a strategy for qualitative data analysis and identify when it is most effectively used

- Formulate an initial grounded theory analysis plan (if appropriate for your research proposal)

What are you trying to accomplish with grounded theory analysis

Just to be clear, grounded theory doubles as both qualitative research design (we will talk about some other qualitative designs in Chapter 22) and a type of qualitative data analysis. Here we are specifically interested in discussing grounded theory as an approach to analysis in this chapter. With a grounded theory analysis, we are attempting to come up with a common understanding (theory) of how some event or series of events occurs based on our examination of participants’ knowledge and experience of that event. Let’s consider the potential this approach has for us as educators in the fight for social justice. Using grounded theory analysis we might try to answer research questions like:

- How do communities identity, organize, and challenge structural issues of racial inequality?

- How do immigrant families respond to threat of family member deportation?

- How has the war on drugs campaign shaped school discipline practices?

In each of these instances, we are attempting to uncover a process that is taking place. To do so, we will be analyzing data that describes the participants’ experiences with these processes and attempt to draw out and describe the components that seem quintessential to understanding this process.

That said, while grounded theory sounds (and is) attractive as a powerful way to make meaning, theory generating research is probably beyond most student research projects. This description is offered here for reference, but probably shouldn’t be the focus of your work at this point in your growing research career.

Variations in the approach

Differences in approaches to grounded theory analysis largely lie in the amount (and types) of structure that are applied to the analysis process. Strauss and Corbin (2014)[15] suggest a highly structured approach to grounded theory analysis, one that moves back and forth between the data and the evolving theory that is being developed, making sure to anchor the theory very explicitly in concrete data points. With this approach, the researcher role is more detective-like; the facts are there, and you are uncovering and assembling them, more reflective of deductive reasoning. While Charmaz (2014)[16] suggests a more interpretive approach to grounded theory analysis, where findings emerge as an exchange between the unique and subjective (yet still accountable) position of the researcher(s) and their understanding of the data, acknowledging that another researcher might emerge with a different theory or understanding. So in this case, the researcher functions more as a liaison, where they bridge understanding between the participant group and the scientific community, using their own unique perspective to help facilitate this process. This approach reflects inductive reasoning.

Coding in grounded theory

Coding in grounded theory is generally a sequential activity. First, the researcher engages in open coding of the data. This involves reviewing the data to determine the preliminary ideas that seem important and potential labels that reflect their significance for the event or process you are studying. Within this open coding process, the researcher will also likely develop subcategories that help to expand and provide a richer understanding of what each of the categories can mean. Next, axial coding will revisit the open codes and identify connections between codes, thereby beginning to group codes that share a relationship. Finally, selective or theoretical coding explores how the relationships between these concepts come together, providing a theory that describes how this event or series of events takes place, often ending in an overarching or unifying idea tying these concepts together. Dr. Tiffany Gallicano[17] has a helpful blog post that walks the reader through examples of each stage of coding. Figure 19.13 offers an example of each stage of coding in a study examining experiences of students who are new to online learning and how they make sense of it. Keep in mind that this is an evolving process and your document should capture this changing process. You may notice that in the example “Feels isolated from professor and classmates” is listed under both axial codes “Challenges presented by technology” and “Course design”. This isn’t an error; it just represents that it isn’t yet clear if this code is most reflective of one of these two axial codes or both. Eventually, the placement of this code may change, but we will make sure to capture why this change is made.

| Open Codes | Axial Codes | Selective |

| Anxious about using new tools | Challenges presented by technology | Doubts, insecurities and frustration experienced by new online learners |

| Lack of support for figuring technology out | ||

| Feels isolated from professor and classmates | ||

| Twice the work—learn the content and how to use the technology | ||

| Limited use of teaching activities (e.g. “all we do is respond to discussion boards”) | Course design | |

| Feels isolated from professor and classmates | ||

| Unclear what they should be taking away from course work and materials | ||

| Returning student, feel like I’m too old to learn this stuff | Learner characteristics | |

| Home feels chaotic, hard to focus on learning |

Constant comparison

While ground theory is not the only approach to qualitative analysis that utilizes constant comparison, it is certainly widely associated with this approach. Constant comparison reflects the motion that takes place throughout the analytic process (across the levels of coding described above), whereby as researchers we move back and forth between the data and the emerging categories and our evolving theoretical understanding. We are continually checking what we believe to be the results against the raw data. It is an ongoing cycle to help ensure that we are doing right by our data and helps ensure the trustworthiness of our research. Ground theory often relies on a relatively large number of interviews and usually will begin analysis while the interviews are ongoing. As a result, the researcher(s) work to continuously compare their understanding of findings against new and existing data that they have collected.

Developing your theory

Remember, the aim of using a grounded theory approach to your analysis is to develop a theory, or an explanation of how a certain event/phenomenon/process occurs. As you bring your coding process to a close, you will emerge not just with a list of ideas or themes, but an explanation of how these ideas are interrelated and work together to produce the event you are studying. Thus, you are building a theory that explains the event you are studying that is grounded in the data you have gathered.

Thinking about power and control as we build theories

I want to bring the discussion back to issues of power and control in research. As discussed early in this chapter, regardless of what approach we are using to analyze our data we need to be concerned with the potential for abuse of power in the research process and how this can further contribute to oppression and systemic inequality. I think this point can be demonstrated well here in our discussion of grounded theory analysis. Since grounded theory is often concerned with describing some aspect of human behavior: how people respond to events, how people arrive at decisions, how human processes work. Even though we aren’t necessarily seeking generalizable results in a qualitative study, research consumers may still be influenced by how we present our findings. This can influence how they perceive the population that is represented in our study. For example, for many years science did a great disservice to families impacted by schizophrenia, advancing the theory of the schizophrenogenic mother[18]. Using pseudoscience, the scientific community misrepresented the influence of parenting (a process), and specifically the mother’s role in the development of the disorder of schizophrenia. You can imagine the harm caused by this theory to family dynamics, stigma, institutional mistrust, etc. To learn more about this you can read this brief but informative editorial article by Anne Harrington in the Lancet.[19] Instances like these should haunt and challenge the scientific community to do better. Engaging community members in active and more meaningful ways in research is one important way we can respond. Shouldn’t theories be built by the people they are meant to represent?

Key Takeaways

- Ground theory analysis aims to develop a common understanding of how some event or series of events occurs based on our examination of participants’ knowledge and experience of that event.

- Using grounded theory often involves a series of coding activities (e.g. open, axial, selective or theoretical) to help determine both the main concepts that seem essential to understanding an event, but also how they relate or come together in a dynamic process.

- Constant comparison is a tool often used by qualitative researchers using a grounded theory analysis approach in which they move back and forth between the data and the emerging categories and the evolving theoretical understanding they are developing.

Resources

Resources for learning more about Grounded Theory

Chun Tie, Y., Birks, M., & Francis, K. (2019). Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers.

Gibbs, G.R. (2015, February 4). A discussion with Kathy Charmaz on Grounded Theory.

Glaser, B.G., & Holton, J. (2004, May). Remodeling grounded theory.

Mills, J., Bonner, A., & Francis, K. (2006). The development of Constructivist Grounded Theory.

A few exemplars of studies employing Grounded Theory

Burkhart, L., & Hogan, N. (2015). Being a female veteran: A grounded theory of coping with transitions.

Donaldson, W. V., & Vacha-Haase, T. (2016). Exploring staff clinical knowledge and practice with LGBT residents in long-term care: A grounded theory of cultural competency and training needs.

Vanidestine, T., & Aparicio, E. M. (2019). How social welfare and health professionals understand “Race,” Racism, and Whiteness: A social justice approach to grounded theory.

19.7 Photovoice

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Explain defining features of photovoice as a strategy for qualitative data analysis and identify when it is most effectively used

- Formulate an initial analysis plan using photovoice (if appropriate for your research proposal)

What are you trying to accomplish with photovoice analysis?

Photovoice is an approach to qualitative research that combines the steps of data gathering and analysis with visual and narrative data. The ultimate aim of the analysis is to produce some kind of desired change with and for the community of participants. While other analysis approaches discussed here may involve including participants more actively in the research process, it is certainly not the norm. However, with photovoice, it is. Using an approach that involves photovoice will generally assume that the participants in your study will be taking on a very active role throughout the research process, to the point of acting as co-researchers. This is especially evident during the analysis phase of your work.

As an example of this work, Mitchell (2018)[20] combines photovoice and an environmental justice approach to engage a Native American community around the significance and the implications of water for their tribe. This research is designed to help raise awareness and support advocacy efforts for improved access to and quality of natural resources for this group. Photovoice has grown out of participatory and community-based research traditions that assume that community members have their own expertise they bring to the research process, and that they should be involved, empowered, and mutually benefit from research that is being conducted. This mutual benefit means that this type of research involves some kind of desired and very tangible changes for participants; the research will support something that community members want to see happen. Examples of these changes could be legislative action, raising community awareness, or changing some organizational practice(s).

Training your team

Because this approach involves participants not just sharing information, but actually utilizing research skills to help collect and interpret data, as a researcher you need to take on an educator role and share your research expertise in preparing them to do so. After recruiting and gathering informed consent, part of the on-boarding process will be to determine the focus of your study. Some photovoice projects are more prescribed, where the researcher comes with an idea and seeks to partner with a specific group or community to explore this topic. At other times, the researcher joins with the community first, and collectively they determine the focus of the study and craft the research question. Once this focus has been determined and shared, the team will be charged with gathering photos or videos that represent responses to the research question for each individual participant. Depending on the technology used to capture these photos (e.g. cameras, ipads, video recorders, cell phones), training may need to be provided.

Once photos have been captured, team members will be asked to provide a caption or description that helps to interpret what their picture(s) mean in relation to the focus of the study. After this, the team will collectively need to seek out themes and patterns across the visual and narrative representations. This means you may employ different elements of thematic or content analysis to help you interpret the collective meaning across the data and you will need to train your team to utilize these approaches.

Converging on a shared story

Once you have found common themes, together you will work to assemble these into a cohesive broader story or message regarding the focus of your topic. Now remember, the participatory roots of photovoice suggest that the aim of this message is to seek out, support, encourage or demand some form of change or transformation, so part of what you will want to keep in mind is that this is intended to be a persuasive story. Your research team will need to consider how to put your findings together in a way that supports this intended change. The packaging and format of your findings will have important implications for developing and disseminating the final products of qualitative research. Chapter 21 focuses more specifically on decisions connected with this phase of the research process.

Key Takeaways

- Photovoice is a unique approach to qualitative research that combines visual and narrative information in an attempt to produce more meaningful and accessible results as an alternative to other traditional research methods.

- A cornerstone of Photovoice research involves the training and participation of community members during the analysis process. Additionally, the results of the analysis are often intended for some form of direct change or transformation that is valued by the community.

Exercises

Reflexive Journal Entry Prompt

After learning about these different types of qualitative analysis:

- Which of these approaches make the most sense to you and how you view the world?

- Which of them are most appealing and why?

- Which do you want to learn more about?

Exercises

Decision Point: How will you conduct your analysis?

- Thinking about what you need to accomplish with the data you have collected, which of these analytic approaches will you use?

- What makes this the most effective choice?

- Outline the steps you plan to take to conduct your analysis

- What peer-reviewed resources have you gathered to help you learn more about this method of analysis? (keep these handy for when you write-up your study!)

Resources

Resources for learning more about Photovice:

Liebenberg, L. (2018). Thinking critically about photovoice: Achieving empowerment and social change.

Mangosing, D. (2015, June 18). Photovoice training and orientation.

University of Kansas, Community Toolbox. (n.d.). Section 20. Implementing Photovoice in Your Community.

Woodgate et al. (2017, January). Worth a thousand words? Advantages, challenges and opportunities in working with photovoice as a qualitative research method with youth and their families.

A few exemplars of studies employing Photovoice:

Fisher-Borne, M., & Brown, A. (2018). A case study using Photovoice to explore racial and social identity among young Black men: Implications for social work research and practice.

Houle et al. (2018). Public housing tenants’ perspective on residential environment and positive well-being: An empowerment-based Photovoice study and its implications for social work.

Mitchell, F. M. (2018). “Water Is Life”: Using photovoice to document American Indian perspectives on water and health.

- Kleining, G., & Witt, H. (2000). The qualitative heuristic approach: A methodology for discovery in psychology and the social sciences. Rediscovering the method of introspection as an example. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(1). ↵

- Burck, C. (2005). Comparing qualitative research methodologies for systemic research: The use of grounded theory, discourse analysis and narrative analysis. Journal of Family Therapy, 27(3), 237-262. ↵

- Mogashoa, T. (2014). Understanding critical discourse analysis in qualitative research. International Journal of Humanities Social Sciences and Education, 1(7), 104-113. ↵

- Contandriopoulos, D., Larouche, C., Breton, M., & Brousselle, A. (2018). A sociogram is worth a thousand words: proposing a method for the visual analysis of narrative data. Qualitative Research, 18(1), 70-87. ↵

- Elliott, L. (2016, January, 16). Dangers of “damage-centered” research. The Ohio State University, College of Arts and Sciences: Appalachian Student Resources. https://u.osu.edu/appalachia/2016/01/16/dangers-of-damage-centered-research/ ↵

- Smith, L. T. (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples (2nd ed.). Zed Books Ltd. ↵

- PAR-L. (2010). Introduction to feminist research. [Webpage]. https://www2.unb.ca/parl/research.htm#:~:text=Methodologically%2C%20feminist%20research%20differs%20from,standpoints%20and%20experiences%20of%20women. ↵

- Mafile'o, T. (2004). Exploring Tongan Social Work: Fekau'aki (Connecting) and Fakatokilalo (Humility). Qualitative Social Work, 3(3), 239-257. ↵