7

Chapter Outline

- What are your assumptions? (16 minute read)

- Ethical and critical considerations (15 minute read)

- Education research paradigms (25 minute read, plus 10 minute video)

- Developing your theoretical framework (15 minute read)

- Designing your project using theory and paradigm (13 minute read)

Content warning: examples in this chapter contain references to post-traumatic stress disorder and similar culture-bound syndromes related to trauma, colonization and Global North/West hegemony, racist beliefs about intelligence and racist science, sexism in medical science and STEM fields, dropping out of high school, poverty, addiction and the disease model, police violence and systemic racism, rape culture, depression, homelessness, “coming out” as a lesbian, ethnocentrism, sexual harassment, domestic violence, and oppression of TANF recipients.

7.1. What are your assumptions?

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Ground your research project and working question in the philosophical assumptions of social science

- Define the terms ‘ontology‘ and ‘epistemology‘ and explain how they relate to quantitative and qualitative research methods

Last chapter, we reviewed the ethical commitment that researchers have to protect the people and communities impacted by their research. Answering the practical questions of harm, conflicts of interest, and other ethical issues will provide clear foundation of what you can and cannot do as part of your research project. In this chapter, we will transition from the real world to the conceptual world. Together, we will discover and explore the theoretical and philosophical foundations of your project. You should complete this chapter with a better sense of how theoretical and philosophical concepts help you answer your working question, and in turn, how theory and philosophy will affect the research project you design.

Embrace philosophy

The single biggest barrier to engaging with philosophy of science, at least according to some of my students, is the word philosophy. I had one student who told me that as soon as that word came up, she tuned out because she thought it was above her head. As we discussed in Chapter 1, some students already feel like research methods is too complex of a topic, and asking them to engage with philosophical concepts within research is like asking asking them to tap dance while wearing ice skates.

For those students, I would first answer that this chapter is my favorite one to write because it was the most personally impactful for me to learn. Finding my theoretical and philosophical home was important for me to develop as an educator and a researcher. Following our advice in Chapter 2, you’ve hopefully chosen a topic that is important to your interests as a social work practitioner, and consider this chapter an opportunity to find your personal roots in addition to revising your working question and designing your research study.

Exploring theoretical and philosophical questions will cause your working question and research project to become clearer…eventually. Consider this chapter as something similar to getting a nice outfit for a fancy occasion. You have to try on a lot of different theories and philosophies before you find the one that fits with what you’re going for. There’s no right way to try on clothes, and there’s no one right theory or philosophy for your project. You might find a good fit with the first one you’ve tried on, or it might take a few different outfits. You have to find ideas that make sense together because they fit with how you think about your topic and how you should study it.

As you read this section, try to think about which assumptions feel right for your working question and research project. Which assumptions match what you think and believe about your topic? The goal is not to find the “right” answer, but to develop your conceptual understanding of your research topic by finding the right theoretical and philosophical fit.

Theoretical & philosophical fluency

In addition to self-discovery, theoretical and philosophical fluency is a skill that educators must possess in order to engage in social justice work. That’s because theory and philosophy help sharpen your perceptions of the social world. Just as educators use empirical data to support their work, they also use theoretical and philosophical foundations. More importantly, theory and philosophy help us build heuristics that can help identify the fundamental assumptions at the heart of education. They alert you to the patterns in the underlying assumptions that different people make and how those assumptions shape their worldview, what they view as true, and what they hope to accomplish. In the next section, we will review feminist and other critical perspectives on research, and they should help inform you of how assumptions about research can reinforce existing oppression.

Understanding these deeper structures is a true gift of research. Because we acknowledge the usefulness and truth value of multiple philosophies and worldviews contained in this chapter, we can arrive at a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the social world. Methods can be closely associated with particular worldviews or ideologies. There are necessarily philosophical and theoretical aspects to this, and this can be intimidating at times, but it’s important to critically engage with these questions to improve the quality of research.

Building your ice float

Although it may not seem like it right now, your project will develop a from a strong connection to previous theoretical and philosophical ideas about your topic. It’s likely you already have some (perhaps unstated) philosophical or theoretical ideas that undergird your thinking on the topic. Moreover, the philosophical questions we review here should inform how you understand different theories and practice modalities, as they deal with the bedrock questions about science and human knowledge.

Before we can dive into philosophy, we need to recall out conversation from Chapter 1 about objective truth and subjective truths. Let’s test your knowledge with a quick example. Is crime on the rise in the United States? A recent Five Thirty Eight article highlights the disparity between historical trends on crime that are at or near their lowest in the thirty years with broad perceptions by the public that crime is on the rise (Koerth & Thomson-DeVeaux, 2020).[1] Educators skilled at research can marshal objective facts, much like the authors do, to demonstrate that people’s perceptions are not based on a rational interpretation of the world. Of course, that is not where our work ends. Subjective facts might seek to decenter this narrative of ever-increasing crime, deconstruct its racist and oppressive origins, or simply document how that narrative shapes how individuals and communities conceptualize their world.

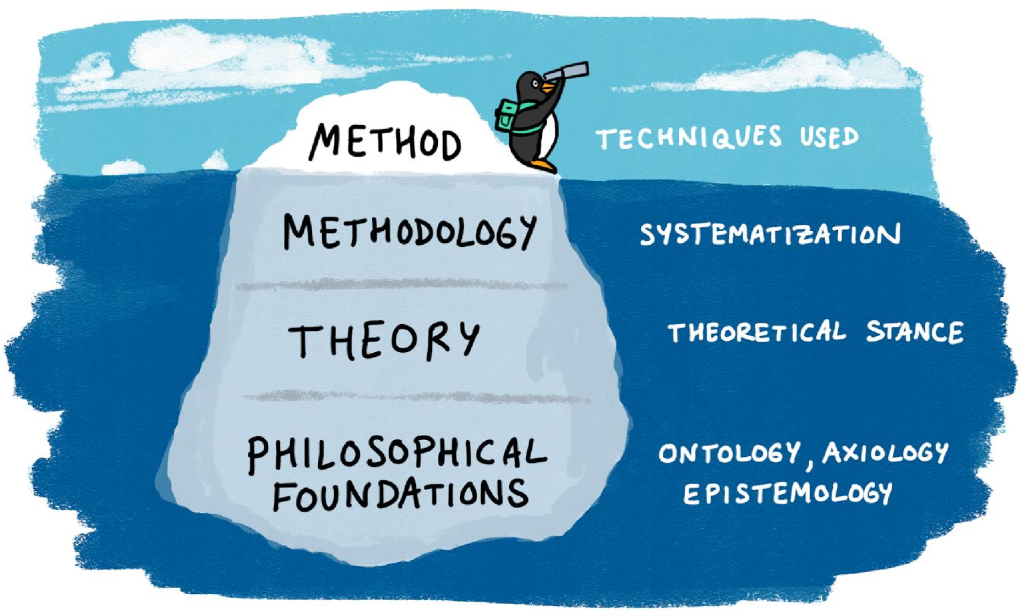

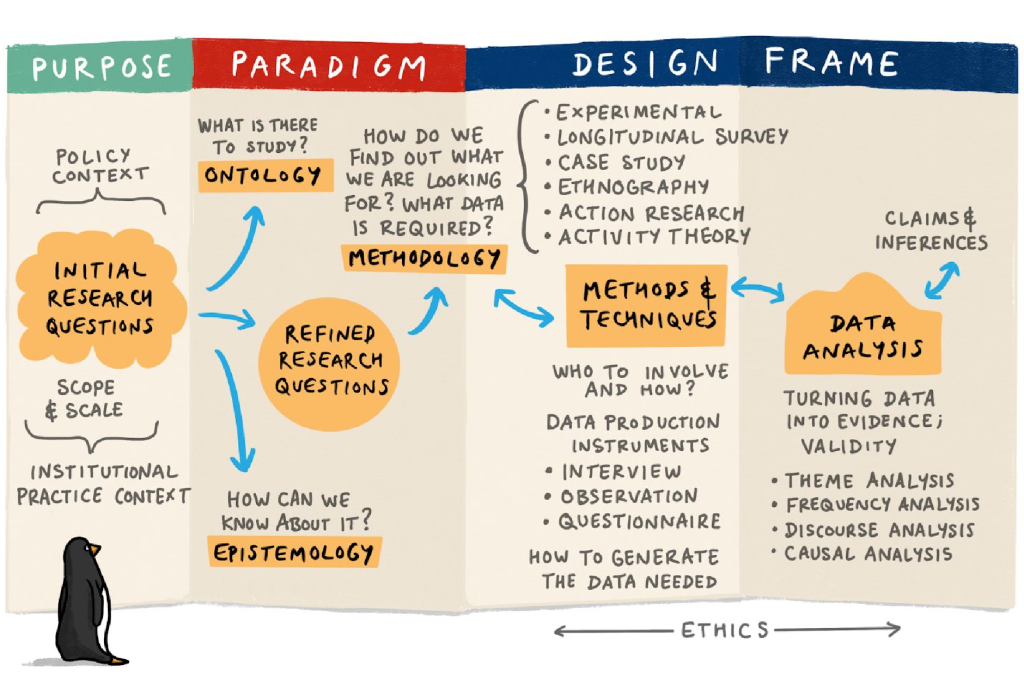

Objective does not mean right, and subjective does not mean wrong. Researchers must understand what kind of truth they are searching for so they can choose a theoretical framework, methodology, and research question that matches. As we discussed in Chapter 1, researchers seeking objective truth (one of the philosophical foundations at the bottom of Figure 7.1) often employ quantitative methods (one of the methods at the top of Figure 7.1). Similarly, researchers seeking subjective truths (again, at the bottom of Figure 7.1) often employ qualitative methods (at the top of Figure 7.1). This chapter is about the connective tissue, and by the time you are done reading, you should have a first draft of a theoretical and philosophical (a.k.a. paradigmatic) framework for your study.

Ontology: Assumptions about what is real & true

In section 1.2, we reviewed the two types of truth that researchers seek—objective truth and subjective truths —and linked these with the methods—quantitative and qualitative—that researchers use to study the world. If those ideas aren’t fresh in your mind, you may want to navigate back to that section for an introduction.

These two types of truth rely on different assumptions about what is real in the social world—i.e., they have a different ontology. Ontology refers to the study of being (literally, it means “rational discourse about being”). In philosophy, basic questions about existence are typically posed as ontological, e.g.:

- What is there?

- What types of things are there?

- How can we describe existence?

- What kind of categories can things go into?

- Are the categories of existence hierarchical?

Objective vs. subjective ontologies

At first, it may seem silly to question whether the phenomena we encounter in the social world are real. Of course you exist, your thoughts exist, your computer exists, and your friends exist. You can see them with your eyes. This is the ontological framework of realism, which simply means that the concepts we talk about in science exist independent of observation (Burrell & Morgan, 1979).[2] Obviously, when we close our eyes, the universe does not disappear. You may be familiar with the philosophical conundrum: “If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?”

The natural sciences, like physics and biology, also generally rely on the assumption of realism. Lone trees falling make a sound. We assume that gravity and the rest of physics are there, even when no one is there to observe them. Mitochondria are easy to spot with a powerful microscope, and we can observe and theorize about their function in a cell. The gravitational force is invisible, but clearly apparent from observable facts, such as watching an apple fall from a tree. Of course, our theories about gravity have changed over the years. Improvements were made when observations could not be correctly explained using existing theories and new theories emerged that provided a better explanation of the data.

As we discussed in section 1.2, culture-bound syndromes are an excellent example of where you might come to question realism. Of course, from a Western perspective as researchers in the United States, we think that the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) classification of mental health disorders is real and that these culture-bound syndromes are aberrations from the norm. But what about if you were a person from Africa experiencing brain fag syndrome (BFS)? Wouldn’t you consider the Western diagnosis of ADHD to be incorrect or incomplete? This conflict raises the question–do either BFS or DSM diagnoses like ADHD really exist at all…or are they just social constructs that only exist in our minds?

If your answer is “no, they do not exist,” you are adopting the ontology of anti-realism (or relativism), or the idea that social concepts do not exist outside of human thought. Unlike the realists who seek a single, universal truth, the anti-realists perceive a sea of truths, created and shared within a social and cultural context. Unlike objective truth, which is true for all, subjective truths will vary based on who you are observing and the context in which you are observing them. The beliefs, opinions, and preferences of people are actually truths that social scientists measure and describe. Additionally, subjective truths do not exist independent of human observation because they are the product of the human mind. We negotiate what is true in the social world through language, arriving at a consensus and engaging in debate within our socio-cultural context.

These theoretical assumptions should sound familiar if you’ve studied social constructivism or symbolic interactionism in your other courses.[3] From an anti-realist perspective, what distinguishes the social sciences from natural sciences is human thought. When we try to conceptualize trauma from an anti-realist perspective, we must pay attention to the feelings, opinions, and stories in people’s minds. In their most radical formulations, anti-realists propose that these feelings and stories are all that truly exist.

What happens when a situation is incorrectly interpreted? Certainly, who is correct about what is a bit subjective. It depends on who you ask. Even if you can determine whether a person is actually incorrect, they think they are right. Thus, what may not be objectively true for everyone is nevertheless true to the individual interpreting the situation. Furthermore, they act on the assumption that they are right. We all do. Much of our behaviors and interactions are a manifestation of our personal subjective truth. In this sense, even incorrect interpretations are “truths”, even though they are true only to one person or a group of misinformed people. This leads us to question whether the social concepts we think about really exist. For researchers using subjective ontologies, they might only exist in our minds; whereas, researchers who use objective ontologies which assume these concepts exist independent of thought.

How do we resolve this dichotomy? As educators, we know that often times what appears to be an either/or situation is actually a both/and situation. Let’s take the example of trauma. There is clearly an objective thing called trauma. We can draw out objective facts about trauma and how it interacts with other concepts in the social world such as family relationships and school performance. However, that understanding is always bound within a specific cultural and historical context. Moreover, each person’s individual experience and conceptualization of trauma is also true. Much like a student who tells you their truth through their stories and reflections, when a participant in a research study tells you what their trauma means to them, it is real even though only they experience and know it that way. By using both objective and subjective analytic lenses, we can explore different aspects of trauma—what it means to everyone, always, everywhere, and what it means to one person or group of people, in a specific place and time.

Epistemology: Assumptions about how we know things

Having discussed what is true, we can proceed to the next natural question—how can we come to know what is real and true? This is epistemology. Epistemology is derived from the Ancient Greek epistēmē which refers to systematic or reliable knowledge (as opposed to doxa, or “belief”). Basically, it means “rational discourse about knowledge,” and the focus is the study of knowledge and methods used to generate knowledge. Epistemology has a history as long as philosophy, and lies at the foundation of both scientific and philosophical knowledge.

Epistemological questions include:

- What is knowledge?

- How can we claim to know anything at all?

- What does it mean to know something?

- What makes a belief justified?

- What is the relationship between the knower and what can be known?

While these philosophical questions can seem far removed from real-world interaction, thinking about these kinds of questions in the context of research helps you target your inquiry by informing your methods and helping you revise your working question. Epistemology is closely connected to method as they are both concerned with how to create and validate knowledge. Research methods are essentially epistemologies – by following a certain process we support our claim to know about the things we have been researching. Inappropriate or poorly followed methods can undermine claims to have produced new knowledge or discovered a new truth. This can have implications for future studies that build on the data and/or conceptual framework used.

Research methods can be thought of as essentially stripped down, purpose-specific epistemologies. The knowledge claims that underlie the results of surveys, focus groups, and other common research designs ultimately rest on epistemological assumptions of their methods. Focus groups and other qualitative methods usually rely on subjective epistemological (and ontological) assumptions. Surveys and and other quantitative methods usually rely on objective epistemological assumptions. These epistemological assumptions often entail congruent subjective or objective ontological assumptions about the ultimate questions about reality.

Objective vs. subjective epistemologies

One key consideration here is the status of ‘truth’ within a particular epistemology or research method. If, for instance, some approaches emphasize subjective knowledge and deny the possibility of an objective truth, what does this mean for choosing a research method?

We began to answer this question in Chapter 1 when we described the scientific method and objective and subjective truths. Epistemological subjectivism focuses on what people think and feel about a situation, while epistemological objectivism focuses on objective facts irrelevant to our interpretation of a situation (Lin, 2015).[4]

While there are many important questions about epistemology to ask (e.g., “How can I be sure of what I know?” or “What can I not know?” see Willis, 2007[5] for more), from a pragmatic perspective most relevant epistemological question in the social sciences is whether truth is better accessed using numerical data or words and performances. Generally, scientists approaching research with an objective epistemology (and realist ontology) will use quantitative methods to arrive at scientific truth. Quantitative methods examine numerical data to precisely describe and predict elements of the social world. For example, while people can have different definitions for poverty, an objective measurement such as an annual income of “less than $25,100 for a family of four” provides a precise measurement that can be compared to incomes from all other people in any society from any time period, and refers to real quantities of money that exist in the world. Mathematical relationships are uniquely useful in that they allow comparisons across individuals as well as time and space. In this book, we will review the most common designs used in quantitative research: surveys and experiments. These types of studies usually rely on the epistemological assumption that mathematics can represent the phenomena and relationships we observe in the social world.

Although mathematical relationships are useful, they are limited in what they can tell you. While you can learn use quantitative methods to measure individuals’ experiences and thought processes, you will miss the story behind the numbers. To analyze stories scientifically, we need to examine their expression in interviews, journal entries, performances, and other cultural artifacts using qualitative methods. Because social science studies human interaction and the reality we all create and share in our heads, subjectivists focus on language and other ways we communicate our inner experience. Qualitative methods allow us to scientifically investigate language and other forms of expression—to pursue research questions that explore the words people write and speak. This is consistent with epistemological subjectivism’s focus on individual and shared experiences, interpretations, and stories.

It is important to note that qualitative methods are entirely compatible with seeking objective truth. Approaching qualitative analysis with a more objective perspective, we look simply at what was said and examine its surface-level meaning. If a person says they brought their kids to school that day, then that is what is true. A researcher seeking subjective truth may focus on how the person says the words—their tone of voice, facial expressions, metaphors, and so forth. By focusing on these things, the researcher can understand what it meant to the person to say they dropped their kids off at school. Perhaps in describing dropping their children off at school, the person thought of their parents doing the same thing. In this way, subjective truths are deeper, more personalized, and difficult to generalize.

Putting it all together

As you might guess by the structure of the next two parts of this textbook, the distinction between quantitative and qualitative is important. Because of the distinct philosophical assumptions of objectivity and subjectivity, it will inform how you define the concepts in your research question, how you measure them, and how you gather and interpret your raw data. You certainly do not need to have a final answer right now! But stop for a minute and think about which approach feels right so far.

Understanding your philosophical assumptions of objectivity and subjectivity is important to the execution of your research. If you are interested in identifying a subjective truth (e.g. how teachers define teaching) but you examine that truth using objective tools (a survey of views of teaching you uncovered in the literature) you may end up identifying only the things you already defined as real (the findings from the literature) and not what teachers actually believe. How many times have you taken a survey and thought to yourself, ‘none of these responses illustrate what I think’? That is a tension between the surveyors’ subject truth as instantiated in the survey and your subject truth as lived through your experience. At the end of the day, that researcher will glean an inaccurate understanding of your experience.

And the flip side is equally true. If you are interested in identifying attrition in teaching ranks (an objective truth), asking teachers if they feel burned out and are thinking about leaving the profession (subjective truths) is not going to tell you whether the teachers actually act on those feelings and leave the profession (the objective truth you were looking for).

In the next section, we will consider another set of philosophical assumptions that relate to ethics and the role of research in achieving social justice.

Key Takeaways

- Philosophers of science disagree on the basic tenets of what is true and how we come to know what is true.

- Researchers searching for objective truth will likely have a different theoretical framework, research design, and methods than researchers searching for subjective truths.

- These differences are due to different assumptions about what is real and true (ontology) and how we can come to understand what is real and true (epistemology).

Exercises

Does an objective or subjective epistemological/ontological framework make the most sense for your research project?

- Are you more concerned with how people think and feel about your topic, their subjective truths—more specific to the time and place of your project?

- Or are you more concerned with objective truth, so that your results might generalize to populations beyond the ones in your study?

Using your answer to the above question, describe how either quantitative or qualitative methods make the most sense for your project.

7.2 Ethical and critical considerations

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Apply feminist, anti-racist, and decolonization critiques of social science to your project

- Define axiology and describe the axiological assumptions of your project

So far, we have talked about knowledge as it exists in the world, but what about the process of research itself? Doesn’t the researcher bring their own biases, perspectives, and experiences to the process? The critique of science as an enterprise dominated by the perspectives of white men from North America and Europe is one that has had a profound impact on how we view knowledge. Because scientists design research studies, create measures, and interpret results, there is always the risk that a scientist’s objectivity slips and as a result, biases are expressed. Even more problematic, unconscious bias can be present in our work without us even realizing it (although there are mechanisms we can use, discussed later, to try and make visible our own unconscious biases).

Consider this example from professional sports. The National Football League (NFL) has long downplayed the lifelong impact of concussions and traumatic brain injury. However, due to the racist science that existed when the issue was first addressed through a settlement in the 1990s, Black players were assumed to have lower cognitive function and were thus any losses in cognitive function were seen as less significant, resulting in a lower payout or additional barriers to an eventual payout (Dale, 2021).[6] It is hard to view this “race-norming” without taking into account the impact of the Bell Curve, a racist and methodologically flawed book that purported to support white intellectual superiority (Bell, 1995).[7] According to an Associated Press report:

The NFL noted that the norms were developed in medicine “to stop bias in testing, not perpetrate it”…The binary race norms, when they are used in the testing, assumes that Black patients start with worse cognitive function than whites and other non-Blacks. That makes it harder for them to show a deficit and qualify for an award. [Two players], for instance, were denied awards but would have qualified had they been white, according to their lawsuit (Dale, 2021, para 10-13).

Part of the value in making the philosophical assumptions of your project explicit is that you can scan for sources of explicit or implicit bias you bring to the research process.

Whose truth does science establish?

Education is concerned with the “isms” of oppression (ableism, ageism, cissexism, classism, heterosexism, racism, sexism, etc.), and so our approach to science must reconcile its history as both a tool of oppression and its exclusion of oppressed groups. Science grew out of the Enlightenment, a philosophical movement which applied reason and empirical analysis to understanding the world. While the Enlightenment brought forth tremendous achievements, the critiques of Marxian, feminist, and other critical theorists complicated the Enlightenment understanding of science. For this section, I will focus on feminist critiques of science, building upon an entry in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Crasnow, 2020).[8]

In its original formulation, science was an individualistic endeavor. As we learned in Chapter 1, a basic statement of the scientific method is that a researcher studies existing theories on a topic, formulates a hypothesis about what might be true, and either confirms or disconfirms their hypothesis through experiment and rigorous observation. Over time, our theories become more accurate in their predictions and more comprehensive in their conclusions. Scientists put aside their preconceptions, look at the data, and build their theories based on objective rationality.

Yet, this cannot be perfectly true. Scientists are human, after all. As a profession historically dominated by white men, scientists have dismissed women and other minorities as being psychologically unfit for the scientific profession. While attitudes have improved, science, technology, engineering, mathematics (STEM) and related fields remain dominated by white men (Grogan, 2019).[9] Biases can persist in theory and research when social scientists do not have similar experiences to the populations they study.

Gender bias can influence the research questions scientists choose to answer. Feminist critiques of medical science drew attention to women’s health issues, spurring research and changing standards of care. The focus on domestic violence in the empirical literature can also be seen as a result of feminist critique. Thus, critical theory helps us critique what is on the agenda for science. If science is to answer important questions, it must speak to the concerns of all people. Through the democratization in access to scientific knowledge and the means to produce it, science becomes a sister process of social development and social justice.

The goal of a diverse and participatory scientific community lies in contrast to much of what we understand to be “proper” scientific knowledge. Many of the older, classic social science theories were developed based on research which observed males or from university students in the United States or other Western nations. How these observations were made, what questions were asked, and how the data were interpreted were shaped by the same oppressive forces that existed in broader society, a process that continues into the present. In psychology, the concept of hysteria or hysterical women was believed to be caused by a wandering womb (Tasca et al., 2012).[10]. Standardized testing, in part, developed to measure the intellectual superiority of white European men and justified Eugenic policies in Canada and internationally[11]. Even today, standardized testing continues to be used in ways that further racial inequality in education (Au, 2015)[12] because the theories underlying testing were created in a sexist and racist culture. In these ways, science can reinforce the truth of the white Western male perspective.

Finally, it is important to note that social science research is often conducted on populations rather than with populations. Historically, this has often meant Western men traveling to other countries and seeking to understand other cultures through a Western lens. Lacking cultural humility and failing to engage stakeholders, ethnocentric research of this sort has led to the view of non-Western cultures as inferior. Moreover, the use of these populations as research subjects rather than co-equal participants in the research process privileges the researcher’s knowledge over that from other groups or cultures. Researchers working with indigenous cultures, in particular, had a destructive habit of conducting research for a short time and then leaving, without regard for the impact their study had on the population. These critiques of Western science aim to decolonize social science and dismantle the racist ideas the oppress indigenous and non-Western peoples through research (Smith, 2013).[13]

The central concept in feminist, anti-racist, and decolonization critiques (among other critical frames) is epistemic injustice. Epistemic injustice happens when someone is treated unfairly in their capacity to know something or describe their experience of the world. As described by Fricker (2011),[14] the injustice emerges from the dismissal of knowledge from oppressed groups, discrimination against oppressed groups in scientific communities, and the resulting gap between what scientists can make sense of from their experience and the experiences of people with less power who have lived experience of the topic. We recommend this video from Edinburgh Law School which applies epistemic injustice to studying public health emergencies, disabilities, and refugee services.

Exercises

- Take a moment and reflect on how your life experiences may inform how you understand your topic. What do you already know? How might you be biased?

- Describe how previous or current studies and theories about your topic have been influenced by oppressive forces such as racism and sexism.

Self-determination and free will

When scientists observe social phenomena, they often take the perspective of determinism, meaning that what is seen is the result of processes that occurred earlier in time (i.e., cause and effect). As you will see in Chapter 9, this process is represented in the classical formulation of a research question which asks “what is the relationship between X (cause) and Y (effect)?” By framing a research question in such a way, the scientist is disregarding any reciprocal influence that Y has on X. Moreover, the scientist also excludes human agency from the equation. It is simply that a cause will necessitate an effect. For example, a researcher might find that few people living in neighborhoods with higher rates of poverty graduate from high school, and thus conclude that poverty causes adolescents to drop out of school. This conclusion, however, does not address the story behind the numbers. Each person who is counted as graduating or dropping out has a unique story of why they made the choices they did. Perhaps they had a mentor or parent that helped them succeed. Perhaps they faced the choice between employment to support family members or continuing in school.

For this reason, determinism is critiqued as reductionistic in the social sciences because people have agency over their actions. This is unlike the natural sciences like physics. While a table isn’t aware of the friction it has with the floor, parents and children are likely aware of the friction in their relationships and act based on how they interpret that conflict. The opposite of determinism is free will, that humans can choose how they act and their behavior and thoughts are not solely determined by what happened prior in a neat, cause-and-effect relationship. Researchers adopting a perspective of free will view the process of, continuing with our education example, seeking higher education as the result of a number of mutually influencing forces and the spontaneous and implicit processes of human thought. For these researchers, the picture painted by determinism is too simplistic.

A similar dichotomy can be found in the debate between individualism and holism. When you hear something like “the disease model of addiction leads to policies that pathologize and oppress people who use drugs,” the speaker is making a methodologically holistic argument. They are making a claim that abstract social forces (the disease model, policies) can cause things to change. A methodological individualist would critique this argument by saying that the disease model of addiction doesn’t actually cause anything by itself. From this perspective, it is the individuals, rather than any abstract social force, who oppress people who use drugs. The disease model itself doesn’t cause anything to change; the individuals who follow the precepts of the disease model are the agents who actually oppress people in reality. To an individualist, all social phenomena are the result of individual human action and agency. To a holist, social forces can determine outcomes for individuals without individuals playing a causal role, undercutting free will and research projects that seek to maximize human agency. Neither approach is wrong or right (arguments can be made for and against each view), they are simply ways of conceptualizing the way in which you view the world (and you should be aware of your own assumptions in world view).

Self Determination Theory and Human Agency

Self Determination Theory[15] is a psychological theory of well being that can be used to bridge the concepts of individual agency (intrinsic motivation) and holism (extrinsic context). SDT posits that people experience well-being and thrive when three conditions are met: they have autonomy (freedom to act); they feel competence (a belief in their ability to succeed); and experience relatedness (membership within a community). It also acknowledges that extrinsic forces–like those created by policies, laws, and social forces–can motivate people to act. These extrinsic forces also limit an individual’s sense of autonomy, and so can interact in fascinating ways with well-being and individual and communal behaviours.

Exercises

- Which assumption, determinism or free will, makes the most sense for your project and working question?

- Is human action, or free will, central to how you understand your topic?

- Or are humans more passive and what happens to them more determined by the social forces that influence their life?

- Reflect on how your project’s assumptions may differ from your own assumptions about free will and determinism. For example, my beliefs about self-determination and free will always inform my practice. However, my working question and research project may rely on social theories that are deterministic and do not address human agency.

Radical change

Another assumption scientists make is around the nature of the social world. Is it an orderly place that remains relatively stable over time? Or is it a place of constant change and conflict? The view of the social world as an orderly place can help a researcher describe how things fit together to create a cohesive whole. For example, systems theory can help you understand how different systems interact with and influence one another, drawing energy from one place to another through an interconnected network with a tendency towards homeostasis. This is a more consensus-focused and status-quo-oriented perspective. Yet, this view of the social world cannot adequately explain the radical shifts and revolutions that occur. It also leaves little room for human action and free will. In this more radical space, change consists of the fundamental assumptions about how the social world works.

For example, at the time of this writing, protests are taking place across the world to remember the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police and other victims of police violence and systematic racism. Public support of Black Lives Matter, an anti-racist activist group that focuses on police violence and criminal justice reform, has experienced a radical shift in public support in just two weeks since the killing, equivalent to the previous 21 months of advocacy and social movement organizing (Cohn & Quealy, 2020).[16] Abolition of police and prisons, once a fringe idea, has moved into the conversation about remaking the criminal justice system from the ground-up, centering its historic and current role as an oppressive system for Black Americans. Seemingly overnight, reducing the money spent on police and giving that money to social services became a moderate political position. That support has dropped over time, showing how difficult in can be to change social systems (be they systems of empowerment or oppressions).

A researcher centering change may choose to understand this transformation or even incorporate radical anti-racist ideas into the design and methods of their study. For an example of how to do so, see this participatory action research study working with Black and Latino youth (Bautista et al., 2013).[17] Contrastingly, a researcher centering consensus and the status quo might focus on incremental changes regarding what people currently think about the topic. For example, see this survey of student attitudes on poverty and race that seeks to understand the status quo of student attitudes and suggest small changes that might change things for the better (Constance-Huggins et al., 2020).[18] To be clear, both studies contribute to racial justice. However, you can see by examining the methods section of each article how the participatory action research article addresses power and values as a core part of their research design, qualitative ethnography and deep observation over many years, in ways that privilege the voice of people with the least power. In this way, it seeks to rectify the epistemic injustice of excluding and oversimplifying Black and Latino youth. Contrast this more radical approach with the more traditional approach taken in the second article, in which they measured student attitudes using a survey developed by researchers. Again, both approaches to research are important, and neither is better than the other generally speaking. The important part is being conscious of your intent throughout the project.

Exercises

- Think about how participatory your study will be.

- Traditional studies will be less participatory. You as the researcher will determine the research question, how to measure it, data collection, etc.

- Radical studies will be more participatory. You as the researcher seek to undermine power imbalances at each stage of the research process.

- Pragmatically, more participatory studies take longer to complete and may be less suited to student projects that need to be completed in a short time frame.

- Participatory studies can also be more challenging to gain ethical approvals for given the flexibility required in design and implementation.

Axiology: Assumptions about values

Axiology is the study of values and value judgements (literally “rational discourse about values [a xía]”). In philosophy this field is subdivided into ethics (the study of morality) and aesthetics (the study of beauty, taste and judgement). For the hard-nosed scientist, the relevance of axiology might not be obvious. After all, what difference do one’s feelings make for the data collected? Don’t we spend a long time trying to teach researchers to be objective and remove their values from the scientific method?

Like ontology and epistemology, the import of axiology is typically built into research projects and exists “below the surface”. You might not consciously engage with values in a research project, but they are still there. Similarly, you might not hear many researchers refer to their axiological commitments but they might well talk about their values and ethics, their positionality, or a commitment to social justice.

Our values focus and motivate our research. These values could include a commitment to scientific rigor, or to always act ethically as a researcher. At a more general level we might ask: What matters? Why do research at all? How does it contribute to human wellbeing? Almost all research projects are grounded in trying to answer a question that matters or has consequences. Some research projects are even explicit in their intention to improve things rather than observe them. This is most closely associated with “critical” approaches.

Critical and radical views of science focus on how to spread knowledge and information in a way that combats oppression. These questions are central for creating research projects that fight against the objective structures of oppression—like unequal pay—and their subjective counterparts in the mind—like internalized sexism. For example, a more critical research project would fight not only against gender differences in achievement but on how students have internalized performance assumptions (stereotype threat). Its explicit goal would be to fight oppression and to inform practice on addressing inequities in student achievement. For this reason, creating change is baked into the research questions and methods used in more critical and radical research projects.

As part of studying radical change and oppression, we are likely employing a model of science that puts values front-and-center within a research project. Education research is values-driven, as we are a values-driven profession. Historically, though, most social scientists have argued for values-free science. Scientists agree that science helps human progress, but they hold that researchers should remain as objective as possible—which means putting aside politics and personal values that might bias their results, similar to the cognitive biases we discussed in section 1.1. Over the course of last century, this perspective was challenged by scientists who approached research from an explicitly political and values-driven perspective. As we discussed earlier in this section, feminist critiques strive to understand how sexism biases research questions, samples, measures, and conclusions, while decolonization critiques try to de-center the Western perspective of science and truth.

Linking axiology, epistemology, and ontology

It is important to note that both values-central and values-neutral perspectives are useful in furthering social justice. Values-neutral science is helpful at predicting phenomena. Indeed, it matches well with objectivist ontologies and epistemologies. Let’s examine a measure of motivation, the Academic Motivation Scale (AMS-HS 28, high school edition). The authors of this measure spent years creating a measure that accurately and reliably measures the concept of motivation in high school students. This measure is assumed to measure motivation in any high school student, and scales like this are often translated into other languages (and subsequently validated) for more widespread use. The goal is to measure motivation in a valid and reliable manner. We can use this objective measure to examine motivation across seven sub scales: Intrinsic motivation – to know; Intrinsic motivation – toward accomplishment; Intrinsic motivation – to experience stimulation; Extrinsic motivation – identified; Extrinsic motivation – introjected; Extrinsic motivation – external regulation; and Amotivation.

While measures like the AMS-HS 28 help with prediction, they do not allow you to understand an individual person’s experience of motivation. To do so, you need to listen to their stories and how they make sense of the world. The goal of understanding isn’t to predict what will happen next, but to empathically connect with the person and truly understand what’s happening from their perspective. Understanding fits best in subjectivist epistemologies and ontologies, as they allow for multiple truths (i.e. that multiple interpretations of the same situation are valid). The values commitments researchers make as part of the research process influence them to adopt objective or subjective ontologies and epistemologies.

Exercises

What role will values play in your study?

- Are you looking to be as objective as possible, putting aside your own values?

- Or are you infusing values into each aspect of your research design?

Remember that although social work is a values-based profession, that does not mean that all social work research is values-informed. The majority of social work research is objective and tries to be value-neutral in how it approaches research.

Philosophical assumptions, as a whole

As you engage with theoretical and empirical information in education, keep these philosophical assumptions in mind. They are useful shortcuts to understanding the deeper ideas and assumptions behind the construction of knowledge. See Table 7.1 below for a short reference list of the key assumptions we covered in sections 7.1 and 7.2. The purpose of exploring these philosophical assumptions isn’t to find out which is true and which is false. Instead, the goal is to identify the assumptions that fit with how you think about your working question and your personal worldview.

| Assumptions | Central conflicts |

| Ontology: assumptions about what is real | Realism vs. anti-realism (a.k.a. relativism) |

| Epistemology: assumptions about how we come to know what is real | Objective truth vs. subjective truths

Math vs. language/expression Prediction vs. understanding |

| Assumptions about the researcher | Researcher as unbiased vs. researcher shaped by oppression, culture, and history

Researcher as neutral force vs. researcher as oppressive force |

| Assumptions about human action | Determinism vs. free will

Holism vs. individualism |

| Assumptions about the social world | Orderly and consensus-focused vs. disorderly and conflict-focused |

| Assumptions about the purpose of research | Study the status quo vs. create radical change

Values-neutral vs. values-informed |

Key Takeaways

- Feminist, anti-racist, and decolonization critiques of science highlight the often hidden oppressive ideas and structures in science.

- Even though education is a values-based discipline, many education research projects are values-neutral because those assumptions fit with the researcher’s question.

7.3 Education research paradigms

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Distinguish between the three major research paradigms in education and apply the assumptions upon which they are built to a student research project

In the previous two sections, we reviewed the three elements to the philosophical foundation of a research method: ontology, epistemology and axiology (Crotty, 1998; Guba & Lincoln, 1994; Heron & Reason, 1997).[19] In this section, you will explore how to apply these philosophical approaches to your research project. In the next section, we will do the same for theory. Keep in mind that it’s easy for us as textbook authors to lay out each step (paradigm, theory, etc.) sequentially, but in reality, research projects are not linear. Researchers rarely proceed by choosing an ontology, epistemology and axiology separately and then deciding which theory and methods to apply. As we discussed in Chapter 2 when you started conceptualizing your project, you should choose something that interests you, is feasible to conduct, and does not pose unethical risks to others. Whatever part or parts your project you have figured out right now, you’re right where you should be—in the middle of conceptualization.

How do scientific ideas change over time?

Much like your ideas develop over time as you learn more, so does the body of scientific knowledge. Kuhn’s (1962)[20] The Structure of Scientific Revolutions is one of the most influential works on the philosophy of science, and is credited with introducing the idea of competing paradigms (or “disciplinary matrices”) in research. Kuhn investigated the way that scientific practices evolve over time, arguing that we don’t have a simple progression from “less knowledge” to “more knowledge” because the way that we approach inquiry is changing over time. This can happen gradually, but the process results in moments of change where our understanding of a phenomenon changes more radically (such as in the transition from Newtonian to Einsteinian physics; or from Lamarckian to Darwinian theories of evolution). How did the problems in one paradigm inspire new paradigms? Kuhn presents us with a way of understanding the history of scientific development across all topics and disciplines.

As you can see in this video from Matthew J. Brown (CC-BY), there are four stages in the cycle of science in Kuhn’s approach. Firstly, a pre-paradigmatic state where competing approaches share no consensus. Secondly, the “normal” state where there is wide acceptance of a particular set of methods and assumptions. Thirdly, a state of crisis where anomalies that cannot be solved within the existing paradigm emerge and competing theories to address them follow. Fourthly, a revolutionary phase where some new paradigmatic approach becomes dominant and supplants the old. Shnieder (2009)[21] suggests that the Kuhnian phases are characterized by different kinds of scientific activity.

Newer approaches often build upon rather than replace older ones, but they also overlap and can exist within a state of competition. Scientists working within a particular paradigm often share methods, assumptions and values. In addition to supporting specific methods, research paradigms also influence things like the ambition and nature of research, the researcher-participant relationship and how the role of the researcher is understood.

Paradigm vs. theory

The terms ‘paradigm‘ and ‘theory‘ are often used interchangeably in social science. There is not a consensus among social scientists as to whether these are identical or distinct concepts. With that said, in this text, we will make a clear distinction between the two ideas because thinking about each concept separately is more useful for our purposes.

We define paradigm as a set of common philosophical (ontological, epistemological, and axiological) assumptions that inform research. The four paradigms we describe in this section refer to patterns in how groups of researchers resolve philosophical questions. Some assumptions naturally make sense together, and paradigms grow out of researchers with shared assumptions about what is important and how to study it. Paradigms are like “analytic lenses” and a provide framework on top of which we can build theoretical and empirical knowledge (Kuhn, 1962).[22] Consider this video of an interview with world-famous physicist Richard Feynman in which he explains why “when you explain a ‘why,’ you have to be in some framework that you allow something to be true. Otherwise, you are perpetually asking why.” In order to answer basic physics question like “what is happening when two magnets attract?” or an education research question like “what is the impact of this intervention on achievement,” you must understand the assumptions you are making about social science and the social world. Paradigmatic assumptions about objective and subjective truth support methodological choices like whether to conduct interviews or send out surveys, for example.

While paradigms are broad philosophical assumptions, theory is more specific, and refers to a set of concepts and relationships scientists use to explain the social world. Theories are more concrete, while paradigms are more abstract. Look back to Figure 7.1 at the beginning of this chapter. Theory helps you identify the concepts and relationships that align with your paradigmatic understanding of the problem. Moreover, theory informs how you will measure the concepts in your research question and the design of your project.

For both theories and paradigms, Kuhn’s observation of scientific paradigms, crises, and revolutions is instructive for understanding the history of science. Researchers inherit institutions, norms, and ideas that are marked by the battlegrounds of theoretical and paradigmatic debates that stretch back hundreds of years. We have necessarily simplified this history into four paradigms: positivism, interpretivism, critical, and pragmatism. Our framework and explanation are inspired by the framework of Guba and Lincoln (1990)[23] and Burrell and Morgan (1979).[24] while also incorporating pragmatism as a way of resolving paradigmatic questions. Most of education research and theory can be classified as belonging to one of these four paradigms, though this classification system represents only one of many useful approaches to analyzing social science research paradigms.

Building on our discussion in section 7.1 on objective vs. subjective epistemologies and ontologies, we will start with the difference between positivism and interpretivism. Afterward, we will link our discussion of axiology in section 7.2 with the critical paradigm. Finally, we will situate pragmatism as a way to resolve paradigmatic questions strategically. The difference between positivism and interpretivism is a good place to start, since the critical paradigm and pragmatism build on their philosophical insights.

It’s important to think of paradigms less as distinct categories and more as a spectrum along which projects might fall. For example, some projects may be somewhat positivist, somewhat interpretivist, and a little critical. No project fits perfectly into one paradigm. Additionally, there is no paradigm that is more correct than the other. Each paradigm uses assumptions that are logically consistent, and when combined, are a useful approach to understanding the social world using science. The purpose of this section is to acquaint you with what research projects in each paradigm look like and how they are grounded in philosophical assumptions about social science.

You should read this section to situate yourself in terms of what paradigm feels most “at home” to both you as a person and to your project. You may find, as I have, that your research projects are more conventional and less radical than what feels most like home to you, personally. In a research project, however, students should start with their working question rather than their heart. Use the paradigm that fits with your question the best, rather than which paradigm you think fits you the best.

Positivism: Researcher as “expert”

Positivism has its roots in the scientific revolution of the Enlightenment. Positivism is based on the idea that we can come to know facts about the natural world through our experiences of it. The processes that support this are the logical and analytic classification and systemization of these experiences. Through this process of empirical analysis, Positivists aim to arrive at descriptions of law-like relationships and mechanisms that govern the world we experience.

Positivists have traditionally claimed that the only authentic knowledge we have of the world is empirical and scientific. Essentially, positivism downplays any gap between our experiences of the world and the way the world really is; instead, positivism determines objective “facts” through the correct methodological combination of observation and analysis. Data collection methods typically include quantitative measurement, which is supposed to overcome the individual biases of the researcher.

Positivism aspires to high standards of validity and reliability supported by evidence, and has been applied extensively in both physical and social sciences. Its goal is familiar to all students of science: iteratively expanding the evidence base of what we know is true. We can know our observations and analysis describe real world phenomena because researchers separate themselves and objectively observe the world, placing a deep epistemological separation between “the knower” and “what is known” and reducing the possibility of bias. We can all see the logic in separating yourself as much as possible from your study so as not to bias it, even if we know we cannot do so perfectly.

However, the criticism often made of positivism with regard to human and social sciences (e.g. education, psychology, sociology) is that positivism is scientistic; which is to say that it overlooks differences between the objects in the natural world (tables, atoms, cells, etc.) and the subjects in the social work (self-aware people living in a complex socio-historical context). In pursuit of the generalizable truth of “hard” science, it fails to adequately explain the many aspects of human experience that don’t conform to this way of collecting data. Furthermore, by viewing science as an idealized pursuit of pure knowledge, positivists may ignore the many ways in which power structures our access to scientific knowledge, the tools to create it, and the capital to participate in the scientific community.

Kivunja & Kuyini (2017)[25] describe the essential features of positivism as:

- A belief that theory is universal and law-like generalizations can be made across contexts

- The assumption that context is not important

- The belief that truth or knowledge is ‘out there to be discovered’ by research

- The belief that cause and effect are distinguishable and analytically separable

- The belief that results of inquiry can be quantified

- The belief that theory can be used to predict and to control outcomes

- The belief that research should follow the scientific method of investigation

- Rests on formulation and testing of hypotheses

- Employs empirical or analytical approaches

- Pursues an objective search for facts

- Believes in ability to observe knowledge

- The researcher’s ultimate aim is to establish a comprehensive universal theory, to account for human and social behavior

- Application of the scientific method

Many quantitative researchers now identify as postpositivist. Postpositivism retains the idea that truth should be considered objective, but asserts that our experiences of such truths are necessarily imperfect because they are ameliorated by our values and experiences. Understanding how postpositivism has updated itself in light of the developments in other research paradigms is instructive for developing your own paradigmatic framework. Epistemologically, postpositivists operate on the assumption that human knowledge is based not on the assessments from an objective individual, but rather upon human conjectures. As human knowledge is thus unavoidably conjectural and uncertain, though assertions about what is true and why it is true can be modified or withdrawn in the light of further investigation. However, postpositivism is not a form of relativism, and generally retains the idea of objective truth.

These epistemological assumptions are based on ontological assumptions that an objective reality exists, but postpositivists, they believe reality can be known only imperfectly and probabilistically. While positivists believe that research is or can be value-free or value-neutral, postpositivists take the position that bias is undesired but inevitable, and therefore the investigator must work to detect and try to correct it. Postpositivists work to understand how their axiology (i.e., values and beliefs) may have influenced their research, including through their choice of measures, populations, questions, and definitions, as well as through their interpretation and analysis of their work. Methodologically, they use mixed methods and both quantitative and qualitative methods, accepting the problematic nature of “objective” truths and seeking to find ways to come to a better, yet ultimately imperfect understanding of what is true. A popular form of postpositivism is critical realism, which lies between positivism and interpretivism.

Is positivism right for your project?

Positivism is concerned with understanding what is true for everybody. Educators whose working question fits best with the positivist paradigm will want to produce data that are generalizable and can speak to larger populations. For this reason, positivistic researchers favor quantitative methods—probability sampling, experimental or survey design, and multiple, and well-established instruments to measure key concepts.

A positivist orientation to research is appropriate when your research question asks for generalizable truths. For example, your working question may look something like: does my school’s attendance intervention lead to fewer absences for our students? It is necessary to study such a relationship quantitatively and objectively. When educators speak about social problems impacting societies and individuals, they reference positivist research, including experiments and surveys of the general populations. Positivist research is exceptionally good at producing cause-and-effect explanations that apply across many different situations and groups of people. There are many good reasons why positivism is the dominant research paradigm in the social sciences.

Critiques of positivism stem from two major issues. First and foremost, positivism may not fit the messy, contradictory, and circular world of human relationships. A positivistic approach does not allow the researcher to understand another person’s subjective mental state in detail. This is because the positivist orientation focuses on quantifiable, generalizable data—and therefore encompasses only a small fraction of what may be true in any given situation. This critique is emblematic of the interpretivist paradigm, which we will describe next.

In the section after that, we will describe the critical paradigm, which critiques the positivist paradigm (and the interpretivist paradigm) for focusing too little on social change, values, and oppression. Positivists assume they know what is true, but they often do not incorporate the knowledge and experiences of oppressed people, even when those community members are directly impacted by the research. Positivism has been critiqued as ethnocentrist, patriarchal, and classist (Kincheloe & Tobin, 2009).[26] This leads them to do research on, rather than with populations by excluding them from the conceptualization, design, and impact of a project, a topic we discussed in section 2.4. It also leads them to ignore the historical and cultural context that is important to understanding the social world. The result can be a one-dimensional and reductionist view of reality.

Exercises

- From your literature search, identify an empirical article that uses quantitative methods to answer a research question similar to your working question or about your research topic.

- Review the assumptions of the positivist research paradigm.

- Discuss in a few sentences how the author’s conclusions are based on some of these paradigmatic assumptions. How might a researcher operating from a different paradigm (e.g., interpretivism, critical) critique these assumptions as well as the conclusions of this study?

Interpretivism: Researcher as “empathizer”

Positivism is focused on generalizable truth. Interpretivism, by contrast, develops from the idea that we want to understand the truths of individuals, how they interpret and experience the world, their thought processes, and the social structures that emerge from sharing those interpretations through language and behavior. The process of interpretation (or social construction) is guided by the empathy of the researcher to understand the meaning behind what other people say.

Historically, interpretivism grew out of a specific critique of positivism: that knowledge in the human and social sciences cannot conform to the model of natural science because there are features of human experience that cannot objectively be “known”. The tools we use to understand objects that have no self-awareness may not be well-attuned to subjective experiences like emotions, understandings, values, feelings, socio-cultural factors, historical influences, and other meaningful aspects of social life. Instead of finding a single generalizable “truth,” the interpretivist researcher aims to generate understanding and often adopts a relativist position.

While positivists seek “the truth,” the interpretist / social constructionist framework argues that “truth” varies. Truth differs based on who you ask, and people change what they believe is true based on social interactions. These subjective truths also exist within social and historical contexts, and our understanding of truth varies across communities and time periods. This is because we, according to this paradigm, create reality ourselves through our social interactions and our interpretations of those interactions. Key to the interpretivist perspective is the idea that social context and interaction frame our realities.

Researchers operating within this framework take keen interest in how people come to socially agree, or disagree, about what is real and true. Consider how people, depending on their social and geographical context, ascribe different meanings to certain hand gestures. When a person raises their middle finger, those of us in Western cultures will probably think that this person isn’t very happy (not to mention the person at whom the middle finger is being directed!). In other societies around the world, a thumbs-up gesture, rather than a middle finger, signifies discontent (Wong, 2007).[27] The fact that these hand gestures have different meanings across cultures aptly demonstrates that those meanings are socially and collectively constructed. What, then, is the “truth” of the middle finger or thumbs up? As we’ve seen in this section, the truth depends on the intention of the person making the gesture, the interpretation of the person receiving it, and the social context in which the action occurred.

Qualitative methods are preferred as ways to investigate these phenomena. Data collected might be unstructured (or “messy”) and correspondingly a range of techniques for approaching data collection have been developed. Interpretivism acknowledges that it is impossible to remove cultural and individual influence from research, often instead making a virtue of the positionality of the researcher and the socio-cultural context of a study.

One common objection positivists levy against interpretivists is that interpretivism tends to emphasize the subjective over the objective. If the starting point for an investigation is that we can’t fully and objectively know the world, how can we do research into this without everything being a matter of opinion? For the positivist, this risk for confirmation bias as well as invalid and unreliable measures makes interpretivist research unscientific. Clearly, we disagree with this assessment, and you should, too. Positivism and interpretivism have different ontologies and epistemologies with contrasting notions of rigor and validity (for more information on assumptions about measurement, see Chapter 11 for quantitative validity and reliability and Chapter 20 for qualitative rigor). Nevertheless, both paradigms apply the values and concepts of the scientific method through systematic investigation of the social world, even if their assumptions lead them to do so in different ways. Interpretivist research often embraces a relativist epistemology, bringing together different perspectives in search of a trustworthy and authentic understanding or narrative.

Kivunja & Kuyini (2017)[28] describe the essential features of interpretivism as:

- The belief that truths are multiple and socially constructed

- The acceptance that there is inevitable interaction between the researcher and his or her research participants

- The acceptance that context is vital for knowledge and knowing

- The belief that knowledge can be value laden and the researcher’s values need to be made explicit

- The need to understand specific cases and contexts rather deriving universal laws that apply to everyone, everywhere.

- The belief that causes and effects are mutually interdependent, and that causality may be circular or contradictory

- The belief that contextual factors need to be taken into consideration in any systematic pursuit of understanding

One important clarification: it’s important to think of the interpretivist perspective as not just about individual interpretations but the social life of interpretations. While individuals may construct their own realities, groups—from a small one such as a married couple to large ones such as nations—often agree on notions of what is true and what “is” and what “is not.” In other words, the meanings that we construct have power beyond the individuals who create them. Therefore, the ways that people and communities act based on such meanings is of as much interest to interpretivists as how they were created in the first place. Theories like social constructionism, phenomenology, and symbolic interactionism are often used in concert with interpretivism.

Is interpretivism right for your project?

An interpretivist orientation to research is appropriate when your working question asks about subjective truths. The cause-and-effect relationships that interpretivist studies produce are specific to the time and place in which the study happened, rather than a generalizable objective truth. More pragmatically, if you picture yourself having a conversation with participants like an interview or focus group, then interpretivism is likely going to be a major influence for your study.

Positivists critique the interpretivist paradigm as non-scientific. They view the interpretivist focus on subjectivity and values as sources of bias. Positivists and interpretivists differ on the degree to which social phenomena are like natural phenomena. Positivists believe that the assumptions of the social sciences and natural sciences are the same, while interpretivists strongly believe that social sciences differ from the natural sciences because their subjects are social creatures.

Similarly, the critical paradigm finds fault with the interpretivist focus on the status quo rather than social change. Although interpretivists often proceed from a feminist or other standpoint theory, the focus is less on liberation than on understanding the present from multiple perspectives. Other critical theorists may object to the consensus orientation of interpretivist research. By searching for commonalities between people’s stories, they may erase the uniqueness of each individual’s story. For example, while interpretivists may arrive at a consensus definition of what the experience of “coming out” is like for people who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer, it cannot represent the diversity of each person’s unique “coming out” experience and what it meant to them. For example, see Rosario and colleagues’ (2009)[29] critique the literature on lesbians “coming out” because previous studies did not addressing how appearing, behaving, or identifying as a butch or femme impacted the experience of “coming out” for lesbians.

Exercises

- From your literature search, identify an empirical article that uses qualitative methods to answer a research question similar to your working question or about your research topic.

- Review the assumptions of the interpretivist research paradigm.

- Discuss in a few sentences how the author’s conclusions are based on some of these paradigmatic assumptions. How might a researcher operating from a different paradigm (like positivism or the critical paradigm) critique the conclusions of this study?

Critical paradigm: Researcher as “activist”

As we’ve discussed a bit in the preceding sections, the critical paradigm focuses on power, inequality, and social change. Although some rather diverse perspectives are included here, the critical paradigm, in general, includes ideas developed by early progressive theorists, such as George Counts,[30] and later works developed by scholars such as Paulo Freire (1970).[31] Unlike the positivist paradigm, the critical paradigm assumes that social science can never be truly objective or value-free. Furthermore, this paradigm operates from the perspective that scientific investigation should be conducted with the express goal of social change. Researchers in the critical paradigm foreground axiology, positionality and values . In contrast with the detached, “objective” observations associated with the positivist researcher, critical approaches make explicit the intention for research to act as a transformative or emancipatory force within and beyond the study.

Researchers in the critical paradigm might start with the knowledge that systems are biased against certain groups, such as women or ethnic minorities, building upon previous theory and empirical data. Moreover, their research projects are designed not only to collect data, but to impact the participants as well as the systems being studied. The critical paradigm applies its study of power and inequality to change those power imbalances as part of the research process itself. If this sounds familiar to you, you may remember hearing similar ideas when discussing social conflict theory. Because of this focus on social change, the critical paradigm is a natural home for education research. However, we fall far short of adopting this approach widely in our profession’s research efforts.

Is the critical paradigm right for your project?

Every education research project impacts social justice in some way. What distinguishes critical research is how it integrates an analysis of power into the research process itself. Critical research is appropriate for projects that are activist in orientation. For example, critical research projects should have working questions that explicitly seek to raise the consciousness of an oppressed group or collaborate equitably with community members and clients to addresses issues of concern. Because of their transformative potential, critical research projects can be incredibly rewarding to complete. However, partnerships take a long time to develop and social change can evolve slowly on an issue, making critical research projects a more challenging fit for student research projects which must be completed under a tight deadline with few resources.

Positivists critique the critical paradigm on multiple fronts. First and foremost, the focus on oppression and values as part of the research process is seen as likely to bias the research process, most problematically, towards confirmation bias. If you start out with the assumption that oppression exists and must be dealt with, then you are likely to find it regardless of whether it is truly there or not. Similarly, positivists may fault critical researchers for focusing on how the world should be, rather than how it truly is. In this, they may focus too much on theoretical and abstract inquiry and less on traditional experimentation and empirical inquiry. Finally, the goal of social transformation is seen as inherently unscientific, as positivists believe that science is not a political practice.

Interpretivists often find common cause with critical researchers. Feminist studies, for example, may explore the perspectives of women while centering gender-based oppression as part of the research process. In interpretivist research, the focus is less on radical change as part of the research process and more on small, incremental changes based on the results and conclusions drawn from the research project. Additionally, some critical researchers’ focus on individuality of experience is in stark contrast to the consensus-orientation of interpretivists. Interpretivists seek to understand people’s true selves. Some critical theorists argue that people have multiple selves or no self at all.

Exercises

- From your literature search, identify an article relevant to your working question or broad research topic that uses a critical perspective. You should look for articles where the authors are clear that they are applying a critical approach to research like feminism, anti-racism, Marxism and critical theory, decolonization, anti-oppressive practice, or other social justice-focused theoretical perspectives. To target your search further, include keywords in your queries to research methods commonly used in the critical paradigm like participatory action research and community-based participatory research. If you have trouble identifying an article for this exercise, consult your professor for some help. These articles may be more challenging to find, but reviewing one is necessary to get a feel for what research in this paradigm is like.

- Review the assumptions of the critical research paradigm.

- Discuss in a few sentences how the author’s conclusions are based on some of these paradigmatic assumptions. How might a researcher operating from different assumptions (like values-neutrality or researcher as neutral and unbiased) critique the conclusions of this study?

Pragmatism: Researcher as “strategist”

“Essentially, all models are wrong but some are useful.” (Box, 1976)[32]