H. R. Stoneback

For Everett Raymond Kinstler

I am accused, in England, of uncleanness and pornography. I deny the charge…Lewdness is hateful because it impairs our integrity and our proud being. –D. H. Lawrence, Foreword (1919) Women in Love.

I

Drugstore Paperback Rack 1955

Let us hesitate no longer to announce that the sensual passions and mysteries are equally sacred with the spiritual mysteries.—Lawrence, Foreword Women in Love.

The thirteen-year-old boy surveys the rack,

the drugstore paperbacks. So young, yet still he laughs

at some of the silly, lurid, wannabe sexy

cover art. He thinks, proud of his cleverness:

These covers are about what is uncovered.

One book stands out. His eyes keep returning

to it. He’s no fool, he knows you don’t judge

a book by its cover. In his father’s library

there are many books, many covers:

the truly obscene maroon leatherette

spines of Reader’s Digest Condensed Novels

and the Abridged Classics. His mother loves them.

His father, a real poet, laughs at them.

When the boy reads the condensed books he always

goes back to the real thing, feels a profound

nausea over lost words, images, sentences.

Most of the true Classics are in his father’s

collection, many bound in real leather.

The boy loves the way those books feel in his hands.

His mother never touches them. Words, sentences

don’t matter to her. Boy spins the drugstore rack.

Again, only that one cover catches his eye.

He takes the book from the rack: he’s heard about

the author but never read anything by him.

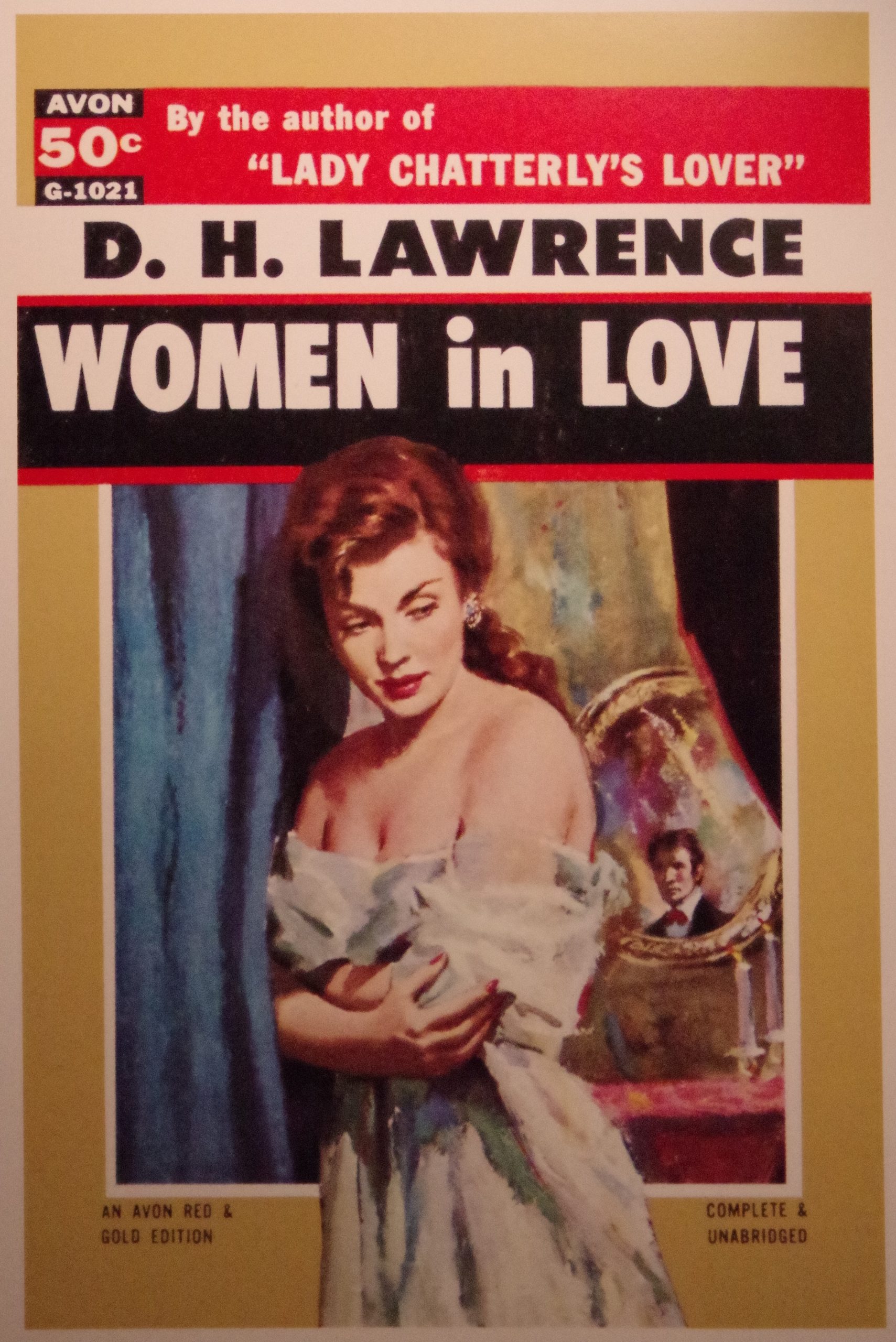

At the top of the cover it says “AVON 50 Cents:

By the Author of Lady Chatterley’s Lover.”

The boy has heard people whisper about that book

but he will have to wait a few more years, until

the obscenity trials are over and the unexpurgated

edition is finally published, to read it. By age 19

he has read all of Lawrence, and he is tired of it.

He tells girls in his Freshman year at college:

Lawrence is a sexual reactionary

but the free speech court decision is important.

But it’s still 1955. He runs his hand over the cheap

paperback. The woman on the cover is lovely,

not lusty-lurid like most of the other covers.

The face-in-the mirror trick is nice, too.

He reads the Author’s Foreword and likes it.

He puts the book back on the rack. His mother

would disapprove of the woman, confiscate her.

He spins the rack again. It stops, like a wheel

of fortune, with the same lovely lady book

in front of hiseyes. What the heck–mother won’t

see it. It’s the last copy. All the other books

have multiple copies. Maybe this one sells

out fast because of the woman on the cover.

He checks the change in his pocket. Left over

from the money he made selling Yum-Yum

in the park on the 4th of July–(Italian

Water Ice is a kind of Reader’s Digest

Yum-Yum)–He has enough for two books.

He sees another Lawrence book. The lady

on the cover of Aaron’s Rod is not as pretty

and she’s with some jerk guy. He takes the book

anyway–already he likes to read everything

by any author he likes. At 13, he laughs

at the cover blurb from the New York Times:

“A book for men and women who are mentally

as well as physically grown up.” How do you write

such crap, such a sloppy sentence and get it published,

he wonders. At 13, he is very sure of himself as a writer,

his confirmed vocation; and, that preface ringing

in his ears and all the cover ladies chattering

he thinksThat’s the way to go, write something

outsexyrageous, get banned so you get readers.

He puts his four quarters on the counter,

goes to the park where he reads 200 pages

before dark. He sees the artist’s name on the cover,

the man who painted the lady that made him buy

the book and he says it: Everett Raymond Kinstler.

It has a nice trochaic sound so he sings it.

(At 13, he’s already been singing in the streets

for tips for four years, a Merry Minstrel.)

So he sings it over and over walking

home in the dark Yessir that’s my baby

Nosir don’t mean maybe lady by Kinstler

Yessir a woman more shimmery than tinsel

II

Meeting the Artist, 60-some Years Later

Amazing virtuosity as a painter . . . Ray is one of those artists who can paint the human form [which] pours out from his fingertips. . . Ray, I think, is very much the future of American art. —Tom Wolfe, Introduction Everett Raymond Kinstler: My Brush with History

60-some years after I bought that Lawrence book

because of the artist’s cover, I met Ray Kinstler.

92 and still painting every day.

Over 100 of his portraits in the National Gallery in D.C.

(I’ve known artists proud that they had two or three.)

Ray’s Presidential Portraits hang in the White House.

Portraits, portraits everywhere, all museums North and South.

In 2017, I met with Ray at his legendary

Studio (since 1949) on Gramercy Park,

at the National Arts Club. I saw a large-format

art book: on the back cover, portrait of a lady I dimly knew.

We went next door to another famous club,

The Players. We had lunch, downstairs in the Grill,

beneath the Kinstler Room where his work adorns the walls.

Kinstler claimed me as his next “victim”

(his name for portrait subjects). His wit and wisdom

charmed me. Through it all I remained stricken

by the lady I could not remember.

When I got home on the midnight train I went

online, bought books on Kinstler’s art I wanted.

The books came: I realized the lady that haunted

memory was Ray’s cover for Women in Love.

And there were two versions, one more risqué.

Ray told me his publishers always demanded,

for the paperback covers, décolletage.

“Breasts,” they cried. Well, that is not what they said

exactly, but you can guess all the rest.

This was one time they wanted something more modest

than what Ray gave them. (Find thatin books about Kinstler).

But when it comes to enigmatic loveliness and looks

old Leonardo’s Mona Lisa

is like some stale diploma thesis

next to Ray’s Laurentian Lady. Décolletage,

a fashion thing, aesthetics, history, persiflage, badinage

(body-neige). We must recall that for ages, all the rage

from the 1400s on, fashionable ladies in evening dress

concealed ankles, revealed completely exposed breasts.

And then Victoria reigned and all things changed.

(Décolletage means shoulders, neck and two hands down.)

Thus I rummaged among my old Lawrence volumes,

found the very copy I had bought in 1955

and there she was, still utterly alive.

III

On Teaching Lawrence 50 Years Ago

The only thing unbearable is the degradation, the prostitution of the living mysteries in us . . . the creative soul, the God-mystery within us. —Lawrence, Foreword Women in Love.

When I began my university teaching career—

hard to believe yesterday was 50 years ago—

by far the most popular courses on campus

were Senior Seminars on Lawrence and Hemingway.

I was not hired to teach them—as my mentor Cleanth Brooks

put it, I was the man for Faulkner and Joyce,

the twinned Southern Renascence/Irish Renaissance voice.

Hemingway and Lawrence were taught by a senior colleague.

When he fell gravely ill I was assigned to take on his classes.

Rereading Hemingway was a revelation, after my

all-too-easy-and-fashionable dismissal of him for years.

But that’s a longer story. Lawrence was a different thing.

I had loved all that Lawrence I read as a teenager.

but as I discovered so many years later

he was not re-readable, and only teachable

because the teenagers, the students loved him.

I lingered on the best, Sons and Lovers,

raced through The Rainbow and the short stories,

and we did almost everything, even late cloudy stuff

and travel books. Even the place-treatment

had that lazy Laurentian fire, overheated,

fireplace ill-tended, risking chimney-fire. Yet esteemed

by critics—Lawrence still tops, from Forster to Leavis:

the great English novelist of the century.

I no longer agreed. I shared some views

of the emerging feminist critique

of poor old Lawrence. And line-by-line,

it was something like rewinding

Whitman after long absence. Still, I reckon a Pact

is useful and perhaps in retirement I’ll get to that.

Nothing is more precipitous than the decline

in Lawrence’s reputation. In the last 30 years.

I have not met one student who has read any Lawrence,

have not seen any sessions on Lawrence at scores

of conferences. (Meanwhile, worldwide, Hemingway soars.)

We do not have the right to scorn the things

we do not read. Maybe he’ll come back some day.

You may have noticed I did not teach Women in Love

in the one Lawrence course I taught 50 years ago.

Maybe that was because I could not order the cheap

Avon paperback with Kinstler’s lady on the outside.

Many years later, after my mother died,

I cleaned up the old summer cottage

that has been in my family for 150 years,

took the old round table on which I write this,

a box or two, remains of boyhood books and records,

the ones my mother did not throw away. In one box,

my drugstore-rack book, my Kinstler-lady called,

that book I thought I hid and she never saw–

She threw other books away but not Women in Love.

My mother kept that book, saved it for me.

the one book among my 20,000

I still judge by the cover, more real than

what’s inside. Kinstler’s cover art captures

what Lawrence called his savage pilgrimage—pèlerinage,

seeking dark soul-mysteries of his mother’s décolletage.