Demetri Kissel

There is a story, perhaps anecdotal, that says Kafka absolutely insisted his story “Metamorphosis” was not published with a cockroach, or bug of any kind, on the cover. Though he was firm at the time, and the first printing didn’t include a bug on the cover, it would only take a very cursory image search to find that many, many publishers did not heed his request. Literary criticism and analysis rarely includes discussion of the paratext, like a cover, book jacket, or preface, as most paratext is contributed by someone other than the author. Covers especially can be influenced by design philosophy of their time, sometimes even more so than the imagery of the text (and these days this is further trumped by a picture or label discussing an upcoming Netflix series or movie). Ultimately, the goal of most paratext is to sell the book, a goal prioritized over accurately representing it, and because the goal is manipulation of thought (with the hope of a sale), covers can have a profound influence on the interpretation of the text they precede. This isn’t usually an influence out of malice, of course, but in the case of texts like the works of Franz Kafka, work that invites the reader closer to struggle with interpretation and image, presenting any interpretation, especially a false interpretation, of his imagery before a reader even meets the text cannot be ignored when discussing literature criticism. The covers should be included in conversation surrounding this literature. Kafka’s imagery is just as vivid as it is unimaginable; a unique experience that forces the reader to engage with the text in a way that is intimate and vulnerable. The paratext doesn’t exist in a vacuum, especially when it is the first part of the book a reader will see, and this conversation is most clear with Kafka’s Metamorphosis, and Gerard Genette’s paratext theory.

Genette discusses that the role of the paratext, as previously stated, is to “present” the text. He explains paratext as the “fringe” attached around the text:

This fringe, in effect, always bearer of an authorial commentary either more or less legitimated by the author, constitutes, between the text and what lies outside it, a zone not just of transition, but of transaction; the privileged site of a pragmatics and of a strategy, of an action on the public in the service, well or badly understood and accomplished, of a better reception of the text and a more pertinent reading–more pertinent, naturally, in the eyes of the author and his allies (Genette “Introduction” 262).

Although some paratext is written by the author, most of it is not. For our examination, we will be looking at what Genette would term “editorial” paratext, and further, what would be called peritext, which means it is attached to the text itself (unlike the epitext that might be found elsewhere, such as letters and interviews). These technical terms appear throughout Genette’s work, so while they are small matters in the analysis to come, it is necessary to define them and their use before moving forward. To continue: Genette’s discussion of the weight of paratext on the perceptions of the reader is key to examining the covers, and how they’ve changed over time (and why it matters). Genette provides a wide definition for paratext, which includes everything from covers, to dedication pages, to advertisements and interviews. Genette’s definitions of paratext even include facts and rumors about the author (he calls this “factual authorial paratext”), which would include our anecdote about Kafka’s wishes for the Metamorphosis cover. He explains,

I call factual that paratext which consists, not in explicit message (verbal or other), but in a fact whose mere existence, if it is known to the public, makes some commentary on the text and bears on its reception… I do not say that one must know it; I only say that those who know it do not read in the same way as those who do not, and that anyone who denies this difference is making fun of us. (Genette “Introduction” 266)

This idea, that having this paratext must implicitly change the interpretation of the text, is exactly the analysis I intend to hold to the covers of Metamorphosis, with some help from another of Genette’s classifications such as an examination of the temporal paratext as well, which means the ways the paratext has changed over time (appeared, disappeared, or been altered), which, to borrow a phrase from Genette himself, we will return to momentarily. Kafka’s work is especially interesting to examine in terms of the paratext because it is (typically) a translated text. Things like a translator’s preface would be an important paratext to examine, and as the work is translated and reprinted, much of the paratext is changed, especially the covers that will be henceforth examined.

While all of Kafka’s imagery, across many books and stories, is vivid and odd and dreamlike, the best case study for an examination of the covers’ impact on interpretation of the text is Metamorphosis. The core image of Metamorphosis is Gregor’s transformation into a bug. What bug? An excellent question. The story opens, “When Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from troubled dreams, he found himself changed into a monstrous cockroach in his bed” (Kafka 87). One would think this would mean a straightforward interpretation, but the continued descriptions are not quite a cockroach, and it is important to remember that for English copies, this is a translated work. In the original German, the word was much more vague. Kafka continues to describe:

He lay on his tough, armoured back, and, raising his head a little, managed to see – sectioned off by little crescent-shaped ridges into segments – the expanse of his arched, brown belly, atop which the coverlet perched, forever on the point of slipping off entirely. His numerous legs, pathetically frail by contrast to the rest of him, waved feebly before his eyes. (Kafka 87)

Kafka crafts his imagery very carefully: Everything there is exactly as he wants us to see it, but what does it add up to? There is no type of bug that perfectly fits this description, and that is entirely the point. There isn’t even very much of a description, when really examined. How many legs would be “numerous”? The brown belly and crescent shaped ridges could be any of a number of bugs. Gregor would be a cockroach, or a centipede, or a tick, or something entirely different. A cricket could fit too, with such a description. Like Gregor Samsa, the reader is disorientated, bewildered, at what Gregor’s body has turned into. Just as he is confused and discovering himself and his situation, so, too, is the reader. While the translation I am reading takes a firm stance on the cockroach interpretation, such a firm interpretation was not clear in the story originally, and this was intentional. Where does this cockroach interpretation come from?

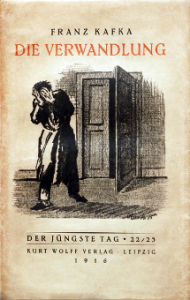

When the story was first published in 1915, Kafka’s demands about the cover were kindly met, as seen in Fig. 1. The bug isn’t pictured, not even from a distance, just as Kafka wanted. The door is ajar, darkness seen within, and a distraught man turns away from it. This is what Kafka wanted. Genette’s examination of audience, who the paratext is addressing and why (and how effectively), and his question of purpose to the message are also in conversation with this examination of covers, though they are perhaps a little easier to answer on a surface level. For this first printing, the audience is slightly different from all future reprintings, simply because they are an audience that has not yet been made familiar with, nor oversaturated by, the infamous concept of Metamorphosis. This first audience is new to the story, unlike later printings, and that is significant when looking at the appearance of the bug on the cover. Because the first cover does not show the bug, a reader is left to struggle with their own interpretation of the text (as Kafka likely intended). Genette speaks of the authority the paratext implicitly has, especially the paratext in closest official proximity to the text. The cover, as an official editorial peritext, carries a great authority on the interpretation of images in the text. There is an interesting point on this first cover in that regard, connected to the purpose of the concept of covers. What is the purpose of a cover? Simply to sell the book, and absolutely nothing further. How well does this first cover succeed? It is interesting in that it preserves the mystery of the bug, allowing the reader to grapple with that image themselves, as Kafka wanted. How much does this draw a reader in? How well does this represent the story? For a moment, I did struggle to place this scene in the story. I believe the best approximation is here: “But the chief clerk had turned his back on Gregor the moment he had begun speaking, and only stared back at him with mouth agape, over his trembling shoulder. All the while Gregor was speaking, he wasn’t still for a moment, but, without taking his eyes off Gregor, moved towards the door, but terribly gradually, as though in breach of some secret injunction not to leave the room” (Kafka 102). However, the fact that this is not immediately clear is troubling, as interesting as the cover is for the time period, the scene isn’t an exact match, according to the Hofman translation, and given the importance of the cover as an advertisement, it is perhaps not surprising that things began to change.

Before moving on to other covers, I would like to make an interesting note on Kafka’s demands on the cover. According to Genette’s definitions, the letter in which Kafka demands no bug ever be on the cover of the book would be “authorial epitext,” a letter separate from the book itself, and written by the author. However, it is also officious, rather than official paratext. Genette explains, “the greater part of the authorial epitext—interviews, conversations and confidences—is officious, because the author can always more or less get rid of his responsibilities by denials such as ‘That is not exactly what I said’” (Genette “Introduction” 267). This is not to say that the officious and the official carry different weights with a reader. A reader who knows of the Kafka anecdote (or any other anecdote, for there are many well-known ones) has their perception changed by knowing, even if they later learn the anecdote was untrue, or misinterpreted, or taken back entirely. Every bit of paratext, even an unofficial anecdote, influences the audience, so how much more so must the cover have this influence? Again, not only is it official, it is typically the first part of the book a reader will see. The complicated part is that even though the cover is editorial in origin, it is often perceived (if not wholly than in part) as authorial. Genette talks about how even the color of the cover can influence its reception (citing historically how covers were color-coded in France), and adds, “…that is where the volumes in the small-sized series Microcosme du Seuil always include an illustration that can- or rather cannot not- serve as paratext” (Genette Paratext 25). Again, we see Genette supporting that these covers influence the reader, and even the pieces that may not be intended to do so, do so. This brings us back to our bug.

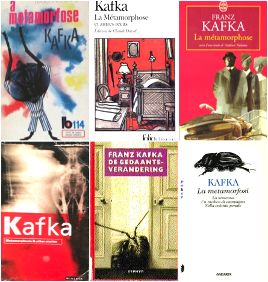

Hofman’s decision to firmly make the bug a cockroach in name may have been influenced by later covers, as most covers from 1915 to present-day appear to have some more of the bug depicted, and it is usually rather cockroach shaped. Jensen, my primary source for a collection of the Metamorphosis covers over the years, claims covers prior to 1950 were difficult to find, or not dated. There is a good collection of various covers from various languages and time periods of Metamorphosis printing, some with the bug and some without.

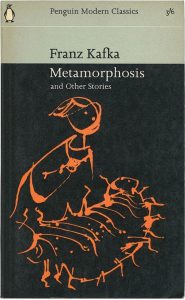

The 1961 Penguin Books cover, pictured in Fig. 2, plainly shows the bug. It is a very interesting minimalist, sketch depiction of the bug on its back, and a figure beside the bug. Here, the bug doesn’t appear to be a cockroach exactly, but some sort of pillbug. A cockroach wouldn’t be a far stretch from there, I would say. The interesting note in this cover, to me, is the size of the bug. This is another point that Kafka does not make extremely clear. In the beginning of the story, it seems Gregor is about the same size as his bed, or bigger. His blanket is falling off him, no longer covering his big bug body (Kafka 87). Gregor does seem to be a larger-than-average bug, but later he hides under tables and chairs (until the furniture is removed from the room, that is). So does he shrink throughout the story? Is he small or large? Another interesting image that Kafka asks a reader to struggle with. The 1961 cover, though the single line drawing is vague, does give us a sense of size as well as an image of the bug before we have even opened the first page. Now, I’ve moved us quite a bit in time, but the importance of this change is that people become more familiar with the story. Certainly, Kafka was reaching fame before the 60s, but by this period there was no doubt of his notoriety, especially Metamorphosis. What does this change? As I hinted before, the audience is entirely different now. This is no longer an audience entirely free of knowledge of this story, so the bug is now in the popular mind. There might be some who have heard nothing of the story, picking up the book for the first time, but unlike with the first cover, where everyone would have to be in that position, that isn’t a guarantee anymore. Where did the cockroach come from? Perhaps one of these covers, but not this 1961 cover. However, there is another term in Genette’s theories that I find interesting to examine these covers with, especially after this very notable change.

We have dealt with what audience has to do with the covers, but I brushed aside purpose as simply marketing. While that is ultimately my point, an analysis is still owed. Genette writes about intent and purpose:

A last pragmatic characteristic of the paratext is what I call, borrowing this adjective very freely from the philosophers of language, the illocutionary force of its message. Here again it is a matter of graduated status. A paratextual element may communicate pure information, for example the name of the author or the date of publication. It may impart an authorial and/or editorial intention or interpretation; this is the cardinal function of most prefaces, and it is still that of the generic indication placed on certain covers or title pages… (Genette “Introduction” 268).

In short, why the paratext is molded and presented the way it is can be divided into both the original goal (the intent) and the practical outcome (the purpose). For example, the intent of a book cover jacket may be to protect the hardcover, but the purpose of such a paratext, as Genette briefly discusses in his book, is to replace the paratext of the cover with further illustration or advertisement (Genette Paratext 30). When the audience is completely new, this illocutionary force of the message of the paratext has to be different than when the story is well known. Perhaps Kafka wanted a reader to grapple with the bug, but a publisher just wants to sell the book. In 1915, it made much more sense to heed Kafka’s wishes, but in 1961 the story was much more well known, and what may be needed to sell the book is simply a strong, unmistakable callback to the story itself. Besides, by 1961, Kafka was no longer present to protest, and people just aren’t frightened of hauntings the way they used to be.

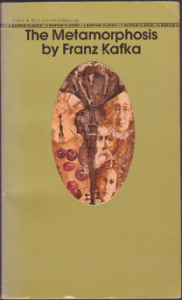

The next cover, from 1972, in Fig 3., is also interesting. The oval contains other distorted scenes from the story, but none of the bug itself. The oval itself could be meant to be the body of the bug (and surely that must, in part, be the intent), but that is also a standard enough shape that it does not feel representative from the cover alone. Only upon reading the story would the oval (and brown coloring) begin to be associated with the image. It is a subtle representation, but does still implant an image for the reader, in part, especially for anyone already familiar with the basics of the story, someone who may think this is a cockroach. I do like the distortion effect on this cover, giving the impression of nightmares, or what a bug-Gregor’s vision could be. That distortion effect is also a striking visual to implant into a reader, but one that may not damage the reader’s own interpretation as much as a bug depiction. Before moving to the next batch of covers, there is another interesting point here: The “cover” as a paratext includes more than the illustration. The cover includes the title of the book, the author’s name, any translator’s name, the publisher’s name, the edition number, the illustration, and many, many more pieces (Genette Paratext 24-26). The farther from 1915 the cover is, it seems the larger Kafka’s name becomes. This is unsurprising; covers sell books, and once an author becomes well known, their name sells the book better than anything else on the cover, however, I do find it interesting when compared to another of Genette’s statements, “a paratextual element is always subordinate to ‘its’ text, and this functionality determines the essentials of its aspect and of its existence” (Genette “Introduction” 269). More or less, the paratext serves the text, and it only continues to appear so long as it serves the text. This is why the covers change over time, both to emphasize the bug, and to emphasize Kafka’s authority. These are the temporal paratext changes, things that come and go, and this increasing authority of Kafka as a writer is why, as even Genette says, “a belated preface does not have the same goals as an original preface” (Genette “Introduction” 269).

The covers up to the present day are more often bug-laden than not, and of those bugs, they are typically cockroaches, or some kind of beetle. There are a few, such as the 1979, 1985, and 1992 covers, that show other kinds of bugs: either crickets or an amalgamation of bug parts. I really enjoy the 1987 cover, depicted along with others in Fig. 4, which shows a bug-headed man in pajamas.

These cover artists were using their own interpretations of the work to draw their chosen bug, and to draw in readers. It is an unfortunate side effect of the attempt here to be creative and expressive, that the cover artists remove that opportunity from the reader by doing so. There is a reason Kafka so adamantly opposed the depiction of a bug on the cover of Metamorphosis, and similar problems exist with Kafka’s other works as well. His imagery is incredibly vivid, but his writing challenges the very act of interpretation. What kind of bug does Gregor Samsa turn into? Hofmann tells us firmly that Gregor wakes as a cockroach, and I am beginning to believe he received that image from other covers. Other translations offer other answers. Kafka himself, perhaps, would like to offer none.

There is one last interesting note from Genette, where in his book he discusses the reprinting of a series of books, and how the author’s portraits are displayed on it. He explains that the publisher used increasingly aged photos of the author as a way to sell the narrative of a long, honorable project. However, all of the books had been written in a relatively short time, when the author was younger, so this progression of time was invented by the publisher (again, as always, to sell books). “For the reader, who certainly pays less attention to the dates given on the flaps than to the look of the pictures themselves, a significant connection is irresistibly established not so much with the chronology of the book’s composition as with the internal chronology of the narrative- that is, the age of the hero” (Genette Paratext 31). He then says that this interpretation isn’t necessarily illegitimate, just that the interpretation is fabricated. That is exactly how I interpret the change in the covers for Metamorphosis. The bug will sell the book (unless, I suppose, a reader is extremely entomophobic, like myself) and even the cockroach interpretation is not necessarily incorrect, or illegitimate, but it is fabricated. It is removed from the original text, the interpretation is what the audience (or rather, the publisher, but I maintain that the wider populace is complicit) puts to the text, rather than what we are taking out of the text.

Interestingly, one of the newest covers for Metamorphosis maintains Kafka’s original wishes and does not include any kind of bug, especially not a cockroach. Pictured in Fig 5. is Peter Mendelsund’s cover, a solid green background, a single great eye, and a bug’s compound eye. Kafka’s name and the title of the book are the same size, and take up a very small portion of the cover, too, which I think does let the book stand for itself. Of course, most people looking for Metamorphosis today know if it already, and know well who wrote it, so it may happen that the name is no longer necessary to sell the book so much as the very knowledge of the title. The art here is definitely evocative of a bug, but not in a way that shows any part of the body. The eye, while not truly indicative of every type of bug, to a layman represents any bug, and shows nothing but an eye that would be described in the book as well. There is also an amazing effect of the book staring at you, at this being two eyes on the face of the cover. The idea of being watched, examined in such a way, is very in line with many of Kafka’s works, and Mendelsund uses the motif of the eye across his Kafka cover designs. Well done, Mendelsund.

Ultimately, I still agree with Kafka’s original wishes. We should keep this bug off the cover, and allow readers to struggle with interpretation themselves. Whatever they decide this bug looks like, or any other Kafka imagery, they will be bettered for it because they have struggled and survived, not because of the image itself. One of the most interesting things (and I am aware the phrase is overused in this paper) that I learned from Genette was the idea that the paratext is not absolute, and not just the cover. The title of the book is not absolute, nor a guarantee, but something that everyone is agreeing to call the book. The author (and further, the publisher) has much less control than the audience does in how a book is defined. Because of that, I think we all owe Kafka an apology for that damned cockroach.

Works Cited

Genette, Gérard. “Introduction to the Paratext.” New Literary History, vol. 22, no. 2, Johns Hopkins UP, 1991, pp. 261–72, doi:10.2307/469037.

—. Paratexts. Cambridge UP, 2001, pp. 23-32.

Jensen, Kelly. “A Metamorphosis Of The Metamorphosis: A Cover Design Exploration”. BOOK RIOT, 2021. www.bookriot.com/metamorphosis-metamorphosis-cover-design-exploration/

Kafka, Franz. “Metamorphosis”. Metamorphosis and Other Stories, Translated by Michael Hofmann, Penguin Classics, 2008.

Wagstaff, Dan. “Peter Mendelsund And The Art Of Metamorphosis | The Casual Optimist”. The Casual Optimist | Books, Design And Culture, 2021,

www.casualoptimist.com/blog/2011/01/27/peter-mendelsund-and-the-art-of-metamorphosis/