20

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Rebut an argument and refute claims. (SLO 1, 2, 3, 4; GEO 1, 2)

- Summarize issues objectively. (SLO 1, 2, 3; GEO 1, 2)

- Recognize weaknesses in argument, such as fallacies. (SLO 1, 2, 3, 4; GEO 1, 2)

- Formulate a counterargument. (SLO 1, 2, 3; GEO 1, 2)

A rebuttal counters or refutes a specific argument. Rebuttals often appear as letters to the editor. They are also used in the workplace to argue against potentially damaging reviews, evaluations, position papers, and reports. Knowing how to write a rebuttal is an important part of defending your beliefs, projects, and research.

Because you will argue with others, trying to gain their understanding and cooperation, you need to understand opposing viewpoints fully. At the same time, you also need to anticipate how readers will respond to your claims and your proofs. After all, something that sounds like a good reason to you may not seem as convincing to readers who do not already share your views.

The main difference between a rebuttal and an argument is that a rebuttal responds directly to the points made in the original argument. After responding to that argument point by point, you then offer a better counterargument.

Introduction and Thesis Statement

A rebuttal essay must show that the writer understands the original argument before attempting to counter it. You must read the original claim carefully, paying close attention to the explanation and examples used to support the point. For example, a claim arguing that schools should enforce mandatory uniforms for its students could support its point by saying that uniforms save money for families and allow students to focus more intently on their studies.

Once you are familiar with the opposing argument, you must write a thesis statement — an overall point for the whole essay. In the case of a rebuttal essay, this single sentence should directly oppose the thesis statement of the original claim which you are countering. The thesis statement should be specific in its wording and content and should be posing a clear argument. For example, if the original thesis statement is “Scientists should not conduct testing on animals because it is inhumane,” you can write “The most humane and beneficial way to test medicine for human illnesses is to first test it on animals.”

Body Paragraphs

The body paragraphs of a rebuttal essay should address and counter the opposing argument point-by-point. A rebuttal can take several approaches when countering an argument, including addressing faulty assumptions, contradictions, unconvincing examples, and errors in relating causes to effects. For every argument you present in a body paragraph, you should provide analysis, explanation, and specific examples that support your overall point. Countering does not only imply disproving a point entirely, but it can also mean showing that the opposing claim is inferior to your own claim or that it is in some way flawed and therefore not credible. Here are some strategies for writing a successful rebuttal:

Summarize the original argument briefly and objectively.

If you’re discussing something “arguable,” then there must be at least one other side to the issue. Show your readers that you understand those other sides before you offer a rebuttal or counter it. If you ignore the opposing viewpoints, your readers will think either that you are unfairly overlooking potential objections or that you just don’t understand the other side of the argument.

You can show readers that you understand other viewpoints by summarizing them fairly and objectively. Early in your argument, try to frame their position in a way that makes your readers say, “Yes, that’s a fair and complete description of the opposing position.”

Summarizing opposing viewpoints strengthens your argument in three ways. First, it lays out the specific points that you can refute or concede when you explain your own position. Second, it takes away some of your opponents’ momentum, because your readers will slow down and consider both sides of the issue carefully. Third, it will demonstrate your goodwill and make you look more reasonable and well-informed.

Recognize when the opposing position may be valid.

The opposing viewpoint probably isn’t completely wrong. In some situations, other views may be partially valid. For example, let’s say you are arguing that the US auto-mobile industry needs to convert completely to manufacturing electric cars within twenty years. Your opponents might argue that this kind of dramatic conversion is not technically or economically feasible.

To show that you are well informed and reasonable, you could name a situation in which they are correct.

Example

By identifying situations in which the opposing position may be valid, you give some ground to the opposing side while limiting the effectiveness of their major points.

Concede some of the opposing points.

When you concede a point, you are acknowledging that some aspects of the opposing viewpoints or objections are valid. While this may expose some of the weaknesses of your own position, it strengthens your argument by strengthening your credibility (ethos).

For instance, if you were arguing that the federal government should use tax-payer money to help the auto industry develop electric cars, you could anticipate two objections to your argument:

- As X points out, production of electric cars cannot be ramped up quickly because appropriate batteries are not being manufactured in sufficient numbers.

- It is of course true that the United States’ electric grid could not handle millions of new electric cars being charged every day.

These objections are important, but they do not undermine your argument entirely. Simply concede that they are problems but demonstrate that they can be fixed or do not matter in the long run.

Example

It is true that the availability of car batteries and the inadequacy of the United States’ electricity grid are concerns. As Stephen Becker, a well-respected consultant to the auto industry, points out, “car manufacturers are already experiencing a shortage of batteries,” and there are no plans to build more battery factories in the future (109). Meanwhile, as Lauren King argues, the United States’ electric grid “is already fragile, as the blackouts a few years ago showed. And there has been very little done to upgrade our electric-delivery infrastructure.” King states that the extra power “required to charge 20 million cars would bring the grid to a grinding halt” (213).

However, there are good reasons to believe that these problems can be dealt with if the right measures are put in place. First, if investors had more confidence that there would be a steady demand for electric cars, and if the government-guaranteed loans for new factories, the growing demand for batteries would encourage manufacturers to bring them to market (Vantz 12). Second, experts have been arguing for years that the United States needs to invest in a nationalized electricity grid that will meet our increasing needs for electricity. King’s argument that the grid is “too fragile” misses the point. We already need to build a better grid, because the current grid is too fragile, even for today’s needs. Moreover, it will take years to build a fleet of 20 million cars. During those years, the electric grid can be rebuilt.

By conceding some points, you demonstrate your knowledge and fairness. By anticipating your readers’ doubts or others’ arguments, you can minimize the challenge to your own argument.

Refute or absorb your opponents’ major points.

In some situations, your opponents will have one or two major points that cannot be conceded without completely undermining your argument. In these situations, you should study each major point to understand why it challenges your own argument. Is there a chance your opponents are right? Could your argument be flawed in some fundamental way? Do you need to rethink or modify your claims, or even change your position?

If you still believe your side of the argument is stronger, you have a few choices. First, you can refute your opponents’ major points by challenging their factual correctness. It helps to look for a “smoking gun” moment in which the opposing side makes a mistake or overstates a claim.

Example

In other situations, you can absorb your opponents’ arguments by suggesting that your position is necessary or is better for the majority.

Example

When absorbing opposing points, you should show that you are aware that they are correct but that the benefits of your position make it the better choice.

Challenge any hidden assumptions behind the author’s claims.

Look for unstated assumptions in each major claim of the author’s reasoning (logical fallacies). These are weak points that you can challenge.

Challenge the evidence.

If the author leaves out important facts and other evidence or uses information that is not accurate or typical, point that out. Locate the original source to see if any data or details are out-dated, inaccurate, exaggerated, or taken out of context.

Challenge the authority of the sources.

If possible, question whether the author’s sources are truly authoritative on the issue (ethological fallacies). Unless a source is rock solid, you can question the reliability of the information taken from it.

Examine whether emotion is overcoming reason or evidence.

If the author is allowing his or her feelings to fuel the argument, you can suggest that these emotions are clouding his or her judgment on the issue (pathological fallacies).

Look for logical fallacies.

Logical fallacies are forms of weak reasoning that you can use to challenge your opponents’ ideas. You can learn more about logical fallacies in Chapter 16: Argumentative Strategies.

Qualify your claims.

You might be tempted to state your claims in the strongest language possible, perhaps even overstating them. In these cases, offer instead a qualified statement.

Examples

Overstatement: The government must use its full power to force the auto industry to develop and build affordable electric cars for the American consumer. The payoff in monetary and environmental benefits will more than cover the investment.

Qualified Statement: Although many significant challenges must be dealt with, the government should begin taking steps to encourage the auto industry to develop and build affordable electric cars for the American consumer. The payoff in monetary and environmental impacts could very well cover the effort and might even pay dividends.

When qualifying your claims and other points, you are softening your position a little. This softening gives readers the sense that they are being asked to make up their own minds. Few people want to be told that they “must” do something or “cannot” do something else. If possible, you want to avoid pushing your readers into making an either/or, yes/no kind of decision, because they may reject your position altogether. Instead, remember that all arguments have gray areas. No one side is absolutely right or wrong. Qualifying your claims allows you to show your readers that your position has some flexibility. You can use the following words and phrases to qualify your claims:

| almost certainly | in all probability | plausibly |

| although | in most circumstances | possibly |

| aside from | in some cases | probably |

| conceivably | may | reasonably |

| could | maybe | should |

| even though | might | unless |

| except | most likely | usually |

| frequently | not including | would |

| if | often | |

| if possible | perhaps |

You can also soften your claims by acknowledging that you are aware of the difficulties and limitations of your position. Your goal is to argue reasonably while strongly advocating for your side of the argument.

Offer a solid counterargument.

Offer a different understanding of the issue supported by authoritative research. Think of it this way: if my argument is that dogs are better pets than cats because they are more social, but you argue that cats are better pets because they are more self-sufficient, your position is a counterargument to my position.

Example: Sample Counterargument Paragraph by Millie Jones (2018)

Some scholars and researchers claim that there are negative impacts of technology on a child’s developing mind. According to one research study, scholars claimed that “moderate evidence also suggests that early exposure to purely entertainment content, and media violence in particular, is negatively associated with cognitive skills and academic achievement” (Kirkorian et al., 2008, p. 8). Although there is validity to the presented argument, this theory excludes educationally driven programming, some of which is specifically designed to educate children beyond what they might experience by age-appropriate schooling alone. There is incredible value in formal education and the public school system; however, classroom modalities are not the only way children learn about the world around them. Educational stimuli can come in the form of direct contact with a teacher, reading a book, or by watching a program. For example, a student learning about the number three can find value in hearing a teacher explain mathematical values of the number, by reading a book that illustrates a visual example of the number, and by watching a program with a catchy song about the number three. In his eBook Children’s Learning From Educational Television: Sesame Street and Beyond, Fisch (2004) described how some television programs are types of informal education, “much like educational activities that children find in magazines, museums, or after-school programs” (p. 9). While a good deal of education takes place in the classroom, television can be used to supplement By including a counterargument paragraph, you show that you know and understand that other positions exist, you have considered these, and you can respond to them. Here, the student identifies the counterargument. The student then begins to respond to the counterargument and states that this opposing argument is incomplete. The student provides both an example and evidence from research that shows the opposing argument is incomplete and not considering alternatives. Created by Millie Jones in 2018; modified November 2020 the academic experience of a student. When presented in an informal and entertaining way, this supplemental material can help students become more engaged in topics, and more willing to delve into deeper consideration of concepts. Early learners may also be introduced to subject matter that is not typically introduced until later phases of formal schooling, if at all (Fisch, 2004). Children and adolescents may also find value in television news programming which provides information on current events, such as Nickelodeon network’s program titled Nick News. This show detailed topical information, such as politics and environmental issues, in an entertaining televised format which was geared to children and adolescents (Fisch, 2004). With all this considered, television and other forms of technology should not be dismissed as petty entertainment; the potential to present educational information in this medium is possibly immeasurable.

Conclusion

The conclusion of your rebuttal essay should synthesize rather than restate the main points of the essay. Use the final paragraph to emphasize the strengths of your argument while also directing the reader’s attention to a larger or broader meaning. Challenge the reader in the essay’s conclusion by calling them action. Like a lawyer’s closing arguments in a court case, the concluding paragraph is the last thing the reader hears; therefore, you should make this section have a strong impact by being specific and straight to the point.

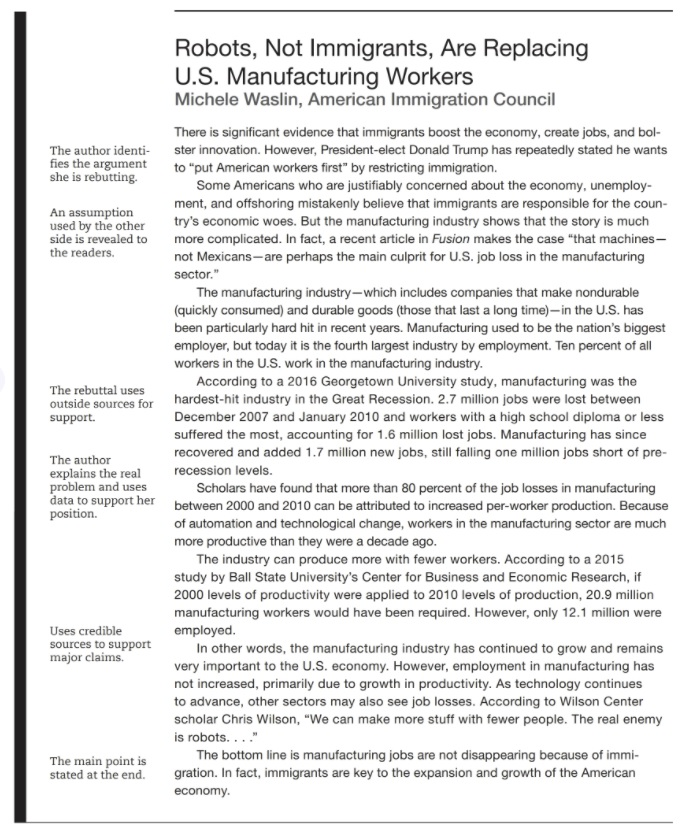

Rebuttal Example #1: “Robots, Not Immigrants, Are Replacing U.S. Manufacturing Workers” by Michele Waslin (American Immigration Council 15 December 2016)

Rebuttal Example #2: “Global Warming Most Definitely Not A Hoax – A Scientist’s Rebuttal” by John Abraham (Catholic Online 16 April 2013)

In a recent Catholic Online interview, we heard from a seemingly reputable person (adjunct faculty member Mark Hendrickson) that global warming is a hoax “perpetrated by those who let a political agenda shape science”. This is a very strong charge that cuts to the professionalism and competence of myself and my colleagues. As a scientist who carries out real research in this area, I can say Dr. Hendrickson is demonstrably wrong. Now, in his defense, Dr. Hendrickson admits he is not an expert, although he “has followed it for over 20 years.” In this field, expertise is judged by research accomplishments. On April 12, 2013, I performed a literature search on Dr. Hendrickson, I could not find a single study he has ever performed and published on any topic, let alone climate change. So, he is clearly not an expert. Of course, Dr. Hendrickson is entitled to his opinion; this is a free country. But to speak authoritatively about a subject he knows little about does a disservice to the readers.

Dr. Hendrickson believes, erroneously, that climate science is like economics. Here he is wrong. Climate science is governed by physical laws (conservation of energy, conservation of mass, gravity, etc.) which have no corollary in economics. It is naive to confuse economics and physical science disciplines.

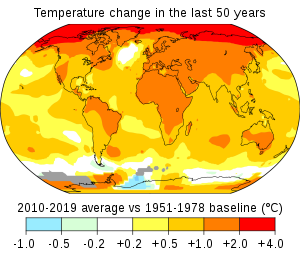

But what about his claims? Are they correct? Not hardly. In his interview, Dr. Hendrickson was asked to explain temperature changes that have already been observed. He responded by belittling computer models. His answer obviously confused past temperature measurements with future predictions of temperatures; they are not the same. The evidence from measurements clearly shows that temperatures have increased significantly over the past 150 years (here and here for example) and temperatures are currently higher than the past few thousand years (here and here for examples). These are but a few of the many studies that show the temperatures we are seeing now are out of the natural range that is expected.

But what about his claims? Are they correct? Not hardly. In his interview, Dr. Hendrickson was asked to explain temperature changes that have already been observed. He responded by belittling computer models. His answer obviously confused past temperature measurements with future predictions of temperatures; they are not the same. The evidence from measurements clearly shows that temperatures have increased significantly over the past 150 years (here and here for example) and temperatures are currently higher than the past few thousand years (here and here for examples). These are but a few of the many studies that show the temperatures we are seeing now are out of the natural range that is expected.

He claimed that satellites have shown no warming in the last two or three decades. This is also false. In fact, even data from two of the most prominent climate skeptics (Dr. John Christy and Dr. Roy Spencer) show temperatures are clearly rising. Their results are confirmed by other satellite organizations and institutes that use other temperature measurement methods such as the Hadley Center, NOAA, and NASA. Even a Koch-brothers funded study has concluded that Earth temperatures are rising and humans are the principle cause.

What about the claim that the Antarctic is gaining mass? Again not true (here and here for example). What about the North Pole? There we have lost an astonishing 75% of the summer ice over the past four decades. Should we be concerned? Dr. Hendrickson is correct in stating that Arctic ice loss won’t raise sea levels much because it is already floating in water. What he doesn’t report is that Arctic ice loss is important for another reason. It helps keep the Earth cool by reflecting sunlight. The loss of this ice has led to an acceleration of the Earth’s temperature rise. If you don’t want to take my word for the importance of Arctic Ice, perhaps we could listen to the Director of the National Snow and Ice Data Center (Mark Serreze). He has characterized Arctic is as in a “death spiral”.

Dr. Hendrickson makes a series of other claims: the medieval times were warmer than today (false), there are 30,000 scientists with advanced degrees who have signed a petition to stop climate action (false), and that there are many scientists who have resigned from government research positions and begun speaking out against the science (he couldn’t recall any names of such scientists).

So what can we make of all of this? First, it is obvious that non-experts like Dr. Hendrickson have every right to provide their opinion in any forum; however, they must be held to the standards of truth and intellectual honesty. When someone makes serial and serious errors in his interpretations, those errors must be called out. Perhaps Dr. Hendrickson truly believes his statements are correct, but his belief does not make them so. This is why we defer to people who know what they are talking about. People who study this every day of their lives. Those people, the real scientists, clearly understand that climate change is a clear and present problem that will only get worse as we ignore it. Failure to deal with climate change will cost us tremendously, in dollars and lives. In fact, two (here and here) recent studies have shown that 97% of the most active climate scientists agree humans are a principal cause of climate change. Among the experts, there is strong agreement. It is up to each of us to decide who to believe (97% of the experts, or Dr. Hendrickson).

But this isn’t all doom and gloom. The good news is there are solutions to this problem. Solutions we can enact today, with today’s technology. If we make smart decisions, we can develop clean and renewable sources of energy. We can light our homes and power our cars while preserving this gifted Earth. Simultaneously, we can create jobs, diversify our energy supply, and improve our national security. Who can be against that?

Failure to act is a choice. It is a choice with tremendous consequences. For me, the path forward is clear.

Rebuttal Example #3: “No, the New COVID-19 Vaccine is Not ‘Morally Compromised” by Amesh A. Adalja (Leaps.org 5 March 2021)

At issue is a cell line used to manufacture the vaccine. Specifically, a cell line used to grow the adenovirus vector used in the vaccine. The purpose of the vector is to carry a genetic snippet of the coronavirus spike protein into the body, like a Trojan Horse ferrying in an enemy combatant, in order to safely trigger an immune response without any chance of causing COVID-19 itself.

It is my hope that the country’s 50 million Catholics do not heed the U.S. Conference of Bishops’ potentially deadly advice and instead obtain whichever vaccine is available to them as soon as possible.

The cell line of the vector, known as PER.C6, was derived from a fetus that was aborted in 1985. This cell line is prolific in biotechnology, as are other fetal-derived cell lines such as HEK-293 (human embryonic kidney), used in the manufacture of the Astra Zeneca COVID-19 vaccine. Indeed, fetal cell lines are used in the manufacture of critical vaccines directed against pathogens such as hepatitis A, rubella, rabies, chickenpox, and shingles and were used to test the Moderna and Pfizer COVID-19 vaccines (which, accordingly, the U.S. Conference of Bishops deem to only raise moral “concerns”).

As such, fetal cell lines from abortions are a common and critical component of biotechnology that we all rely on to improve our health. Such cell lines have been used to help find treatments for cancer, Ebola, and many other diseases.

Dr. Andrea Gambotto, a vaccine scientist at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, explained to Science magazine last year why fetal cells are so important to vaccine development: “Cultured [nonhuman] animal cells can produce the same proteins, but they would be decorated with different sugar molecules, which—in the case of vaccines—runs the risk of failing to evoke a robust and specific immune response.” Thus, the fetal cells’ human origins are key to their effectiveness.

So why the opposition to this life-saving technology, especially in the midst of the deadliest pandemic in over a century? How could such a technology be “morally compromised” when morality, as I understand it, is a code of values to guide human life on Earth with the purpose of enhancing well-being?

By any measure, the J&J vaccine accomplishes that, since human life, not embryonic or fetal life, is the standard of value. An embryo or fetus in the earlier stages of development, while harboring the potential to grow into a human being, is not the moral equivalent of a person. Thus, creating life-saving medical technology using cells that would have otherwise been destroyed is not in conflict with a proper moral code. To me, it is nihilistic to oppose these vaccines on the grounds cited by the U.S. Conference of Bishops.

Reason, the rational faculty, is the human means of knowledge. It is what one should wield when approaching a scientific or health issue. Appeals from clerics, devoid of any need to tether their principles to this world, should not have any bearing on one’s medical decision-making.

In the Dark Ages, the Catholic Church opposed all forms of scientific inquiry, even castigating science and curiosity as the “lust of the eyes”: One early Middle Ages church father reveled in his rejection of reality and evidence, proudly declaring, “I believe because it is absurd.” This organization, which tyrannized scientists such as Galileo and murdered the Italian cosmologist Bruno, today has shown itself to still harbor anti-science sentiments in its ranks.

It is my hope that the country’s 50 million Catholics do not heed the U.S. Conference of Bishops’ potentially deadly advice and instead obtain whichever vaccine is available to them as soon as possible. When judged using the correct standard of value, vaccines using fetal cell lines in their development are an unequivocal good — while those who attempt to undermine them deserve a different category altogether.

Rebuttal Example #4: “Why We Need Not Fear the Fairy Tale” by Mary Rose Somarriba (Verily 31 October 2018)

These stories were written not to trick children into dangerous situations, but to teach lessons of caution.

Disney princesses and #MeToo have shared headlines recently, in a weird way. In some ways it’s a classic attempt at clickbait to make people crazy, but since it’s touching on some cultural notes that are gaining traction—criticism of Disney princesses as problematic for feminism—I couldn’t help but read on.

Actress Kristen Bell, who voice-acted the role of Anna in Frozen, told Parents magazine that she alerts her kids to problematic elements in Disney princess movies like Snow White. “Don’t you think that it’s weird that the prince kisses Snow White without her permission?” Bell recalled asking her daughters. “Because you can not kiss someone if they’re sleeping!”

Similarly, Bell asks her daughters, “Don’t you think it’s weird that Snow White didn’t ask the old witch why she needed to eat the apple? Or where she got that apple? . . . I would never take food from a stranger, would you?”

The New York Post highlighted Bell’s commentary alongside words actress Keira Knightley shared on The Ellen Show in which she criticized Cinderella who “waits around for a rich guy to rescue her. Don’t! Rescue yourself. Obviously!” And regarding The Little Mermaid, Knightley exclaimed, “The songs are great, but do not give your voice up for a man. Hello.” The actress has banned the films from her home.

As a feminist, I get the criticism of some of the Disney princess tropes of the past. I can appreciate critical observations of Disney princess storylines, reminding our daughters that their lives aren’t meaningless without men, and that it’s not OK to make sexual advances on sleeping people—I really hear what they’re saying and see why it’s worth noting. I don’t think those are the biggest messages in these stories, but I do think they can provide fodder for us to have age-appropriate discussion of real issues with our kids.

Where I think we can start losing perspective, though, is if we think we need to ban our kids from viewing these films. First, if we start banning storylines that have protagonists making bad decisions (like taking the food from a stranger, or gambling one’s well-being for a love interest), we’ll have no lessons to share with kids at all.

Second, I think the criticism of Disney princesses who did nothing redeemable but be saved by a prince is a bit short-sighted. Snow White endured refugee status after being kicked out from her home—the free life of her choosing having been disrupted by a tyrannical queen. But the prince’s coming to her wasn’t a show of prowess on his part; Snow White knew the prince before her crisis and literally prayed on screen for him to come to her aid. Romantic relationships aren’t an affront to feminism, are they?

Or take Cinderella, who was enslaved and suffered many hardships. Her fate was changed not by a man directly, but by her choosing not to give up hope when tempted to despair in the garden (cue the entrance of the supernatural aid, the Fairy Godmother).

Fairy Tales Don’t Normalize Abuse—They Warn Against It

The biggest culprit for some feminists is “true love’s kiss.” But this is less a plot device of exploitative proportions and more a literary symbol of true love between a man and a woman. It’s telling that the men in these stories display no evidence otherwise of exploiting the princesses in any of these storylines. These plot devices are not normalizing the activity of making sexual advances on sleeping girls; they are visual representations of the power of love to bring someone back to life.

To think somehow the Disney story writers or the fairy-tale writers of ages past are responsible for any amount of the exploitation of women today is ridiculous; does anyone really think it’s boys’ exposure to princess stories that influenced our rape crisis? (If we’re concerned about content boys are watching we should be concerned about the rape porn boys as young as eleven are being exposed to.)

Now, if we want to pause and tell our kids that Snow White’s kiss is not a scene to replicate literally, that’s fine! I am all for fostering active conversations about things we’re watching with our kids. But if we’re looking to highlight abusive behavior for our kids, we might start with the clear signs of abuse written into the storylines (evil stepmother, anyone?).

Clearly fairy tales are not the source of our culture’s problems with consent and abuse, but since these are real problems for girls growing up (boys co-ercing girls into sexting is a major problem today, for instance, as Peggy Orenstein demonstrates in her book Girls & Sex), these films provide opportunities for us as parents to discuss problematic social issues with our kids. Ariel gave up her voice in The Little Mermaid—so we can talk with our daughters: “How did that help Ariel achieve her goal of getting to know Eric? It didn’t! She was tricked by Ursula and her bad choice did not help her but hurt her.” It’s a cautionary tale of what not to do.

Same with Snow White accepting the apple from the evil queen; these stories offer great opportunities to have intelligent discussions with our daughters about how to behave wisely, and how to spot unsafe behavior in others—starting with bullying step-sisters or powerful, jealous antagonists. This is actually what fairy tales are all about—not to trick children into dangerous situations, but to teach lessons of caution to protect readers and viewers from harms of the world. Indeed for the women in these fairy tales, their lessons ultimately empowered them to come back from a whole range of abuses, turn over a new leaf, and start again.

The practice of rebutting (to contradict or oppose by formal legal argument, plea, or countervailing proof) or refuting (to expose the falsity of).

(of a person or their judgment) not influenced by personal feelings or opinions in considering and representing facts.

To expose the falsity of.