31

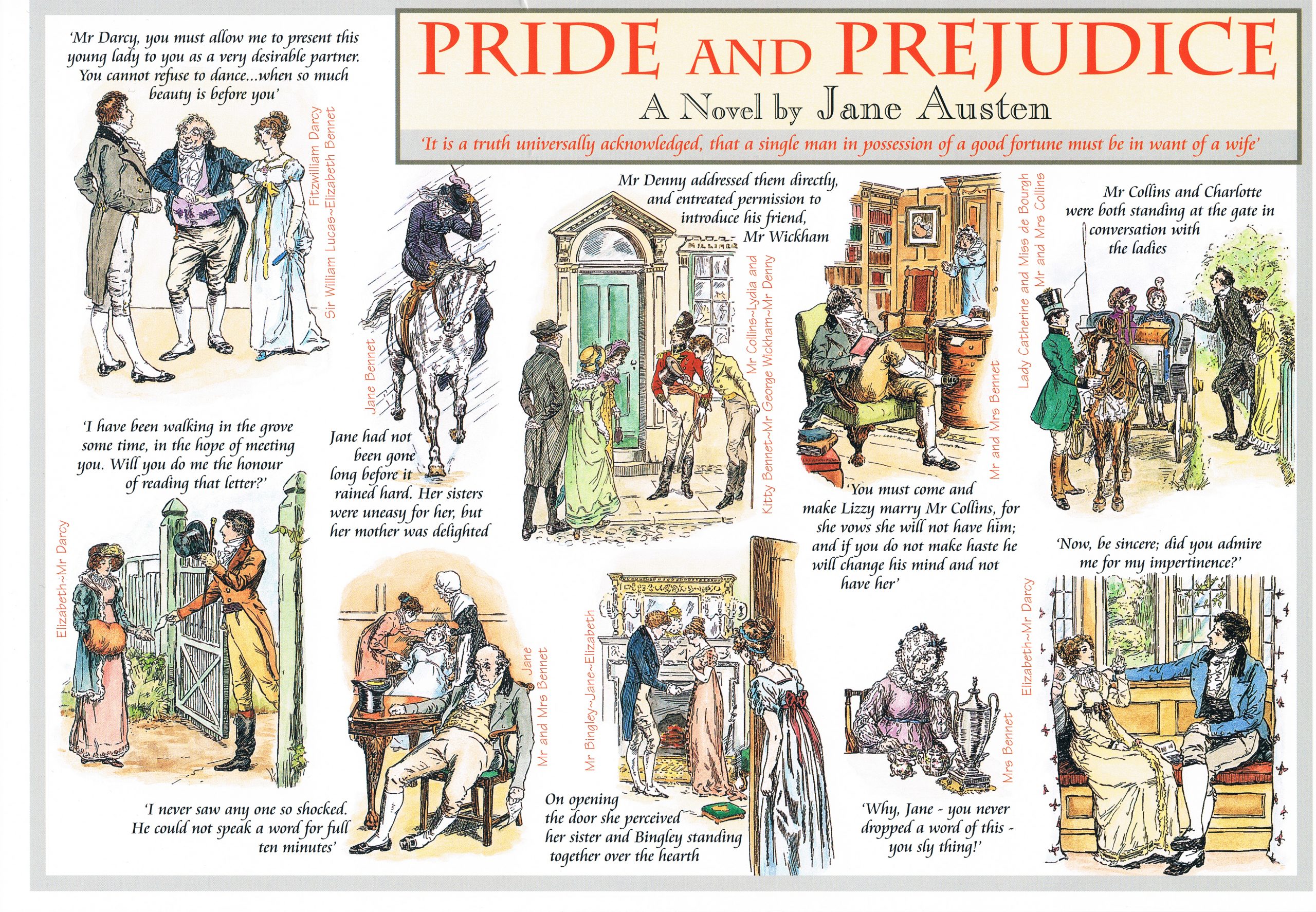

Long before Austenmania overtook America and England in the mid-1990s, when major films and television miniseries were produced of Jane Austen’s most popular novel, Pride and Prejudice, and three other of the six novels Austen completed as an adult, fans reported a private, proprietary sense of “Jane,” as though the great English novelist were a close acquaintance. Rudyard Kipling exploited this phenomenon in his short story “The Janeites,” which describes several members of a secret Jane Austen society, a group of soldiers in the trenches of World War I, well-versed in Austen trivia and gallant defenders of “Jane” and the world she created. Both the jealously guarded private fantasy and the recent popular cultural phenomenon may be attributed in part to the enduring power of Austen’s genius as a writer: her ability to create singular characters who linger in one’s imagination, her unparalleled sense of irony and wit, her brilliant dialogue, and her carefully woven plots. At the same time, Austen delivers a satisfying romance, more so in Pride and Prejudice than in her other novels, and the sheer happiness of her main characters at the novel’s end has its own appeal.

Long before Austenmania overtook America and England in the mid-1990s, when major films and television miniseries were produced of Jane Austen’s most popular novel, Pride and Prejudice, and three other of the six novels Austen completed as an adult, fans reported a private, proprietary sense of “Jane,” as though the great English novelist were a close acquaintance. Rudyard Kipling exploited this phenomenon in his short story “The Janeites,” which describes several members of a secret Jane Austen society, a group of soldiers in the trenches of World War I, well-versed in Austen trivia and gallant defenders of “Jane” and the world she created. Both the jealously guarded private fantasy and the recent popular cultural phenomenon may be attributed in part to the enduring power of Austen’s genius as a writer: her ability to create singular characters who linger in one’s imagination, her unparalleled sense of irony and wit, her brilliant dialogue, and her carefully woven plots. At the same time, Austen delivers a satisfying romance, more so in Pride and Prejudice than in her other novels, and the sheer happiness of her main characters at the novel’s end has its own appeal.

Above all though, and in Pride and Prejudice especially, Austen appeals to modern readers’ nostalgia for a world of social, moral, and economic stability, but one where characters are free to make their own choices and pursue their hearts’ desires. The formal civility, the carefully prescribed manners, and sexual and social restraint, set against a backdrop of village community, stately manor houses, and an English landscape devoid of industrial turmoil and the brisk pace of modern technology—these are a welcome escape for today’s reader. So, too, the heroine Elizabeth Bennet’s bold independence and insistence on placing individual preference above economic motive in marriage satisfies our desire for a plot shaped through the pursuit of personal fulfillment. A convention of morality tales of Austen’s time is that individuals’ personal freedoms and aspirations cannot be easily reconciled with their responsibilities to family and community. Austen overcomes this difficulty by employing the classic comic form: When wedding bells are about to ring at the story’s conclusion, we know that the two sets of main characters have made marriages of affection (Elizabeth’s sister Jane and Mr. Bingley) or even passion (Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy) and that these happy unions actually enhance the stability of society. That it appears to the reader reasonable that Elizabeth follows her heart and ends up fabulously wealthy attests to Austen’s powers of crafting a story in which early hostilities and inappropriate desires are deftly reconciled, and far more realistically so than in comedies by Shakespeare, where happy resolutions must be affected either by wildly improbable coincidences or supernatural forces.

It is sometimes said that Austen’s gift was to be a shrewd observer of her narrow, genteel social circle, that her experience and knowledge of the world were limited and her life sheltered, and that her novels realistically reflect the peaceful late-eighteenth-and early-nineteenth century village community and English countryside she inhabited. That Austen was a careful observer of human motivation and social interaction is certainly true. One should not assume, though, that her choice to write novels of manners means that she was unaware of or unaffected by the political and social upheaval of her day. The idea that she centers her novels on the social classes with which she was most familiar is not entirely the case, although she had occasion to observe members of the gentry and aristocracy whose circumstances resembled those of some of the characters who populate her novels. Whether her own life was perfectly serene is questionable: Most lives, no matter how uneventful in retrospect, have their vicissitudes.

At the very least, Austen and her family must have had concerns over the tumultuous historical events that unsettled the British nation during their lifetime. She was born in 1775, the year that marked the beginning of the American Revolution. Several decades later, she would read newspaper accounts of another British conflict with the new American nation in the War of 1812, which began as she finished revising Pride and Prejudice. What must have played significantly in Austen’s imagination, as in the mind of every Briton, was the ongoing war with Napoleon’s forces, which marked the culmination of a century of conflicts between Britain and France, and which ended, with the Battle of Waterloo in June 1815, six months before her fortieth birthday. The British fear of invasion by Napoleon, which endured until 1805, caused concern even in the towns and villages that seemed safest. Austen would have been aware of the billeting of British militia troops in the English countryside, and she certainly followed the career of her brother Henry, who had joined the Oxford militia in 1793, when Britain’s latest war with France erupted in the aftermath of the French Revolution. She must also have taken a personal interest in the campaigns of the British navy, which counted her brothers Francis and Charles among its officers. To what extent she cared about daily political events is difficult to discern, for her letters are marked by characteristic irony. Of a newspaper report of an 1811 battle of the Peninsular War, when Napoleon invaded Spain and Portugal in an effort to close ports to British commerce, Austen declared, “How horrible it is to have so many people killed!—And what a blessing that one cares for none of them!” (Le Faye, Jane Austen’s Letters, p. 191).

If history and politics in general, and the war with France in particular, seem far removed from the affairs of Austen’s novels, it is worth remembering that the militia and army provide romantic distraction in the form of dashing young officers for the two youngest Bennet sisters, Kitty and Lydia, in Pride and Prejudice, while her final novel, Persuasion, centers on the romantic interests of British naval officers. A feature of Austen’s comic mode is that the events that produce the greatest instability within the British nation are tamed into the material of harmless social disarray that furthers the romantic plot. We find the same process at work in other of her novels. Several scholars have noted that the Bertram family estate of Mansfield Park must be supported by the West Indian slave economy and that Sir Thomas Bertram’s absence from his home in England in order to protect his interests in Antigua provides the occasion for the Bertram children and their friends to engage in the mildly improper behavior that promotes comic disorder. We are also reminded of local instability when Harriet Smith, of Emma, is accosted by a band of gypsies and must be rescued by Frank Churchill; the incident plays on commonly held fears of the vagrants and highway- men who traveled the roads of England.

Austen’s firsthand experiences of the world and its momentous events seem limited if we consider her life in terms of the travels that might have spurred her writer’s imagination. Unlike many of her contemporaries whose literary work was enriched by journeys to Scotland, Ireland, and the European continent, Austen spent most of her relatively short life—she died in 1817 at age forty-one, possibly of Addison’s disease or of a form of lymphoma—in the small villages and towns and countryside of the county of Hampshire, in the south of England. Despite several visits to London, vacation tours throughout southern England, and several years’ residence in the spa city of Bath and in the port town of Southampton, Austen can hardly be called cosmopolitan, and, in any case, she would have preferred to think of herself as provincial, a description that better suits her sense of her subject matter as a writer.

In a letter to her niece Anna Austen, an aspiring novelist, she dispensed the now famous advice that “3 or 4 Families in a Country Village is the very thing to work on” (Letters, p. 275). Austen’s life appears to have been relatively untroubled, although there must have been painful episodes. The daughter of a respectable Anglican clergyman, she was the seventh of eight children in what appears to have been a happy, stable family. There were, however, financial troubles, and the Reverend George Austen was obliged to add to his income by establishing a boarding school for boys in the Austen home and by borrowing money from his sister and her husband. Further, as Austen’s biographer Claire Tomalin points out, even though the family was close, several of the children spent a considerable amount of time living away from home, which, though not unusual for the gentry and professional classes at this time, was probably disorienting for Austen and her siblings. One of her six brothers, George, was disabled—possibly a deaf-mute—and was sent from home for most of his long life. Jane, too, was sent from home, first to a village nurse and later to two boarding schools that, if they resembled the typical girls’ schools of that era, were characterized by bad food, dull teachers, and an atmosphere ripe for one epidemic or another. Along with her older sister, Cassandra, the seven-year-old Jane spent only two seasons at the first institution, where she nearly died from a contagious fever that spread through the school. At age nine, she was sent to a second school, which, if not damaging, was not beneficial either. Although her parents chose to terminate her formal education when she was ten, her father gave her access to his library of some five hundred volumes, and he encouraged his daughter’s literary interests. It was he, in fact, who first tried, unsuccessfully, in 1797, to have an early version of Pride and Prejudice published.

Austen’s immediate family was solidly professional, unlike that of her heroine Elizabeth Bennet, whose father is a member of the gentry, which is to say that his wealth is inherited and tied to land ownership, rather than earned through work or commerce. Austen’s eldest brother, James, followed his father into the ministry, while Henry, the brother who served for several years in the militia, turned next to banking, and then, when his bank failed, followed his father and elder brother into the ministry. The two naval officers, Francis and Charles, both rose to the rank of admiral. Austen’s father and brothers were hardworking, responsible, family-oriented men, so it makes sense that in Pride and Prejudice Austen satirizes snobbish and frivolous members of those classes above hers, the gentry and the aristocracy, who would have looked down upon her own immediate family, just as she paints an unsympathetic portrait of the haughty social climber Caroline Bingley, who fancies herself a member of the gentry, even though her family’s wealth was made “in trade,” or through commerce. Nor, if we consider Austen’s own unaffected outlook, is it surprising that the most sensible characters in the novel, Mr. and Mrs. Gardiner, not only make their money in trade but are apparently not embarrassed to live near their warehouse. Elizabeth Bennet herself descends from lower gentry, on her father’s side, while her maternal grandfather was an attorney.

Despite her allegiance to professionals and businessmen, Austen clearly had respect for what she would have regarded as the nobler values of the landed gentry and aristocracy, particularly the sense of social responsibility and decorum that are implicitly endorsed by the narrator and main characters of the novel. Although these values are fostered through the preservation of a strict social hierarchy, they do not happen to thwart the aspirations of the fictional Elizabeth Bennet, and thus modern readers need never confront the injustices of an English society that remained wary of the new democratic values espoused in America and France and among English radicals. Moreover, even if Austen’s own immediate family fell socially and economically a degree below that of her central fictional characters, her family connections made the upper orders not wholly unknown to her. Austen’s mother, Cassandra Leigh Austen, was descended from a distinguished family and was related to the duke of Chandos. Austen’s first cousin, Eliza Hancock, was goddaughter to Warren Hastings, the eminent statesman and governor of British India, and wife to a member of the French nobility, Count Jean François Capot de Feuillide, who was guillotined during the Reign of Terror. Austen’s brother Edward was literally adopted into the British gentry when Thomas and Catherine Knight, second cousins of the Austens, took an interest in him, obtained permission to raise him, and, finding themselves childless, ultimately made him heir to their splendid estate of Godmersham Park in Kent.

Austen’s own situation in a family of well-connected professionals was somewhat precarious, for she remained unmarried in an age when women depended largely on male relatives for support. Her father and brothers, however, with their strong sense of family responsibility, must have made her feel more secure than the typical “spinster” would have felt. She and her sister Cassandra, who also remained unmarried and was Jane’s closest friend and confidante, were initially dependent on their father, and then, after his death in 1805, on a small annuity and on the generosity of their brothers. Jane Austen had always lived in her father’s house; upon his death, she, her sister, and their mother took up lodgings and visited extensively with relatives and friends for three years. The women eventually settled in the Hampshire village of Chawton, in a house made available to them by Edward. Austen spent the final eight years of her life at Chawton, and it was from this house that she published her novels.

Given how centered her novels are on the marriage plot and how family-oriented her immediate society was, it is worth commenting on Austen’s choice to remain single. In 1802, she received and accepted a proposal from Harris Bigg-Wither, a pleasant young man, Oxford educated and heir to the impressive Manydown estate in Hampshire, close to Austen’s family home at Steventon. She quickly changed her mind, however, and rejected the proposal the day after having accepted it. It seems that while Jane liked Harris, she was not in love with him, and this was enough to give her pause. Her decision was remarkable, for even though romantic love had increasingly become an acceptable incentive for marriage, Austen was a dutiful daughter who lived in an age when friendship, economic motive, family ties, and religious duty were at least as compelling as personal choice. In declining Harris Bigg-Wither’s proposal, Austen made a choice not nearly so dramatic in its disregard for economic considerations as that of her fictional heroine Elizabeth Bennet in declining Mr. Darcy, but one that was similarly impractical. It is hard to say whether Austen simply flew in the face of convention and unwisely put her economic future at risk, or whether she knew that with so many successful and dutiful brothers someone would maintain her somehow.

Claire Tomalin suggests that Austen compared Harris Bigg-Wither unfavorably to Tom Lefroy, to whom she had had a romantic attachment several years earlier, one severed by his relatives, who were concerned about the imprudence of such a match —Austen was, after all, no heiress. Now that she was heading into her late twenties and had grown accustomed to life as a spinster aunt, it is also possible that Austen took a long, hard look at motherhood and decided that its joys were not worth the grief. Throughout the eighteenth century and long afterward, the mortality rates for newborns and women during childbirth was high. The trend in British society to encourage frequent and numerous pregnancies put women at even greater risk. In 1808 Austen’s brother Edward’s wife, Elizabeth, died giving birth to her eleventh child. Her brother Charles’s wife, Fanny, died during childbirth in 1814, at age twenty-four, with her fourth child, who also died several weeks later. In 1823, a few years after Austen’s own death, her brother Francis’s wife, Mary, died giving birth to her eleventh child. Understandably, Austen’s letters demonstrate a mixed attitude toward marriage and motherhood. To her niece Fanny Knight, Austen wrote shortly before her own death that “Single Women have a dreadful propensity for being poor— which is one very strong argument in favour of Matrimony.” On the other hand, she continued with sage advice, “Do not be in a hurry; depend upon it, the right Man will come at last And then, by not beginning the business of Mothering quite so early in life, you will be young in Constitution, spirits, figure & countenance.” Earlier she had cautioned Fanny against entering into a marriage of convenience by remarking, “When I consider. . . how capable you are . . . of being really in love . . . I cannot wish you to be fettered” (Letters, pp. 332, 286).

While it was not unheard of for a woman to have both a family and a writing career in the eighteenth century, it was undoubtedly the case that Austen’s marital status made her writing life much easier. There is, however, no evidence to suggest that she deliberately chose to forsake marriage in order to write books about it. In fact, the extent to which Austen actually saw herself as a writer, as someone whose identity was shaped through her writing and who might have been interested in earning money or fame by doing so, is a matter of debate. She may have described herself, with alternating irony and seriousness, as someone who took up the pen in her idle hours, the way one might take up fancy needlework or china painting. Yet she clearly had a lifelong passion for writing—she authored an impressive collection of juvenilia as well as mature novels—and it seems difficult to believe that she regarded her art as a mere hobby, even if she did not flaunt her gifts publicly. If she did not claim the kind of psychological and material entitlement, the room of one’s own that in the early twentieth century Virginia Woolf would identify as essential for women writers, she did come to depend on the money her novels earned. She became, whether she wished it or not, a professional writer in an age when the market in novels by women and for women was already well established. Pride and Prejudice was published anonymously, as were the works of many women writers to whom publicity seemed indelicate, and while Austen did not court fame, she nevertheless created a stir with her first publication, Sense and Sensibility (1811).

Austen’s second published novel, Pride and Prejudice, appeared at the beginning of 1813, after having been revised the previous year. A first version of the novel, the manuscript of which is now lost, had been written many years earlier, between October 1796 and August 1797. Austen called that early version “First Impressions,” a suggestive title that draws upon stock associations with conduct books to point a moral lesson: One’s first impressions of character should be mistrusted or at least managed with caution; opinion and judgment must be formed through careful reflection and consultation.

Although rooted in a didactic message about first impressions, Austen’s exploration of the subsequent themes of Pride and Prejudice is far more textured than any superficial association with conduct manuals would suggest. The phrase “Pride and Prejudice” held currency in eighteenth-century literature, but, as the editor R. W. Chapman has shown, Austen appears to have borrowed it most immediately from the closing pages of Frances Burney’s novel Cecilia. (In addition to reading the Bible and Shakespeare, Austen inherited a formidable tradition of eighteenth- century works, and the novels of Burney and Samuel Richardson appear to have influenced her considerably; she also turned to popular didactic tales and moral essays for her subject matter and was especially fond of the writings of Dr. Johnson.)

With good reason, scholars have typically viewed Pride and Prejudice in Austen’s novel as distinctly unfavorable qualities, for when the narrator and principal characters evoke “pride” and “prejudice,” the terms have primarily unfavorable connotations, as they do in the world at large. To be sure, Austen assails family pride and social prejudice through the merciless portraits of self- centered individuals. By exposing Mrs. Bennet’s tribalism and Lady Catherine’s snobbery, she offers an amusing indictment of polite society. It should give us pause, however, that Elizabeth Bennet’s overly bookish sister, Mary, pontificates against pride by imitating the trite morality of conduct manuals. (What a shame that Mr. Collins hadn’t thought to marry her.) That is, if Austen calls undue Pride and Prejudice into question, she also regards shallow pieties about those qualities with irony.

Moreover, for an author whose comic closure depends upon an affirmation of the values of the gentry and aristocracy, pride is not simply arrogance. Rather, it marks a legitimate sense that one’s exalted position in society makes one accountable to uphold those values and to behave in a manner worthy of one’s rank. Under a gentleman’s code of honor, the vestiges of which still existed in Austen’s day, pride is closely affiliated with valor and strength of character. Prejudice, too, does not always signify a tendency to make careless, hasty, or harmful judgments. Writing in 1790 on the revolution in France he so deplored, Edmund Burke regarded prejudice as a protection of time-honored custom and the consensus of generations of wise and noble minds, while the revolutionary individual’s so-called reason, by contrast, is prone to error and narrow self-interest. “Prejudice,” Burke wrote, “renders a man’s virtue his habit. . . . Through just prejudice, his duty becomes part of his nature” (Reflections on the Revolution in France, p. 76). Burke’s appeal to virtue, duty, and tradition would have resonated with Austen’s society in the early nineteenth century, when the revolutionary language of Britain’s radical thinkers of the previous generation, considered seditious in the 1790s, was still regarded with suspicion. The notion of affirming Pride and Prejudice, even in moderation, may be difficult for today’s readers to accept, but Austen did not live in a democratic society, where Pride and Prejudice surely thrive but where they are not usually regarded as necessary components of political and social organization. In Austen’s world, these qualities of discrimination helped to preserve the correct social alliances and were integral to the stability of the order of things, even when exhilarating—or menacing— new possibilities for social mobility began to impinge upon the consciousness and writings of English provincials such as Austen.

The exploration of Pride and Prejudice through Austen’s principal characters, Elizabeth and Darcy, is instructional but also multifaceted. The heroine’s early prejudices against Darcy and in favor of Wickham—an inappropriate set of judgments formed by Elizabeth’s having put too much weight on first impressions and circumstantial evidence—are made possible by an excess of pride in her own ability to read character. Darcy’s pride of place, his disdain for social inferiors who lack a proper sense of their own provincialism, leads to a blanket prejudice against nearly every local at the assembly room ball. And yet there is something defensible in these weaknesses: Elizabeth proves herself a thoughtful judge of character in most instances, while Darcy is not entirely amiss in his estimation of a party of lower gentry who are eager to ape the manners of the great but who lack the true social refinement that he himself possesses. In this novel of emotional growth, Pride and Prejudice are not flaws for Elizabeth and Darcy to overcome but character traits that require minor adjustments before the couple can recognize each other’s merits and live happily together.

Even when Pride and Prejudice impair judgment, Elizabeth and Darcy remain principled, perceptive, and admirably strong-minded. As Darcy puts it, in a critique of his friend Mr. Bingley’s complaisance, “To yield without conviction is no compliment to [one’s] understanding” (p. 50), while Elizabeth declares of herself that “There is a stubbornness about me that never can bear to be frightened at the will of others. My courage always rises with every attempt to intimidate me” (p. 173). This strength of personality—she calls it her “impertinence” and he “the liveliness of your mind” (p. 367)—draws an initially unimpressed Darcy to Elizabeth. Further, when evidence presents itself, Elizabeth is able to turn her keen powers of perception inward. Through Darcy’s letter to her, she quickly recognizes her errors, which ability sets her apart from someone like her own undiscerning mother. Although the scene of humiliation and painful self- recognition—“Till this moment, I never knew myself” (p. 205)—that

follows Elizabeth’s reading of the letter is more the stuff of Greek tragedy than of the novel of manners, its presence in the narrative demonstrates that Elizabeth has the capacity for introspection.

Pride and Prejudice seem an almost indispensable set of character traits, or qualities worth cultivating, when we detect the effects of their virtual absence from the personalities of Jane and Mr. Bingley, both of whose easy manners and thorough failures to discriminate put a nearly permanent end to their relationship. Early in the novel, Elizabeth finds Jane too self-effacing, too good- natured, and not critical enough: “You are a great deal too apt, you know, to like people in general. You never see a fault in any body. All the world are good and agreeable in your eyes. I never heard you speak ill of a human being in my life” (p. 16). This assessment may say as much about Elizabeth’s own forcefulness of personality as it does about Jane’s easygoing manners, but Elizabeth has a point. In this instance, Elizabeth is teasing, but she also means what she says, especially when it becomes apparent that Jane wrongly considers the Bingley sisters as agreeable as she does their brother. It is this particular fault that nearly undoes Jane’s romance with Bingley, for the Bingley sisters, her professed friends, have snubbed her long before she realizes it; once she does, her mild manners prevent her from asserting her own interests with their brother. Bingley, too, shows a “want of resolution” (p. 136) to protect his own affairs of the heart. When Darcy misconstrues Jane’s quiet amiability as lack of sufficient interest in Bingley, he easily manipulates his friend into leaving Netherfield and Jane’s presence.

One could argue that the presence of professional and commercial men and women in the novel should militate against the easy acceptance not only of Pride and Prejudice but of other characteristics of the gentry. Even though members of professional and commercial society appear in the novel, however, they aspire to the lifestyle of the gentry and adopt its values and habits. We do not find Austen’s characters embracing those qualities that were well established as virtues and self-consciously adopted among middle-class reformers in her day— efficiency, frugality, punctuality, self-reliance, and the work ethic—and that she herself may have prized. In fact, when we look at the world of the novel, we see hardly any work being done or business being transacted. Certainly, when a team of horses is unavailable to be harnessed to the carriage that might convey Jane Bennet to Netherfield, we become vaguely aware that Mr. Bennet is a gentleman farmer who oversees a working farm. But Austen chooses not to introduce us to farmhands at work, as novelists of social realism would do a generation after hers. We are also very much aware of the presence of soldiers who presumably engage in training exercises if not in actual warfare, but we see them only as dancers at the ball and as romantic distractions for idle young ladies. We become acquainted with the man of commerce Mr. Gardiner only when he is on a holiday tour, and we never actually behold Mr. Collins ministering to his parishioners. In fact, Mr. Collins’s identity as a clergyman is construed solely in terms of the house and property the living brings him. Nor do we hear of commerce in action, except for the occasional ironic reference, as when Lydia Bennet, living out the absurd logic of England’s relatively new consumer culture, buys a hat she knows is ugly simply for the sake of spending money.

What Austen foregrounds throughout the novel is a culture of leisure. In an age when the values of the gentry and aristocracy still prevailed, leisure was understood not only as a respite from labor, as it would have been for those who had to work for a living, but as a way of life that had its own virtues and failings. As in the worlds of classical Greece and Rome so admired by the eighteenth- century society into which Austen was born, a life of leisure at one’s country seat —construed as “retirement” from the daily concerns of commerce and petty political and financial intrigue in London—was considered essential for any gentleman who would take on the responsibilities of disinterested participation in politics and the administration of empire. Especially in the early eighteenth-century of Austen’s grandparents, known in poetry as the Augustan Age for its neoclassical values, those who depended on income from sources other than land—that is, commercial or professional interests—would have seemed compromised in their ability to rise above the concern for personal gain to serve the public good. The country gentry, however, whose values were articulated by Lord Bolingbroke and Augustan poets such as Alexander Pope, regarded themselves as being at leisure for virtuous study and reflection, and as having the power to rise above the corruption, favoritism, and factional-ism that dominated London politics.

In Pride and Prejudice, Mr. Darcy provides the model for the virtuous country gentleman, even though he keeps a house and has acquaintances in London. While we never see Mr. Darcy in his role as keeper of the public interest, or managing his estate, we feel assured that he is the kind of man who inhabits his country estate responsibly. When Darcy negotiates the Lydia- Wickham elopement crisis with authority and competence, we sense that he manages all his life’s affairs with similar capability. That he husbands his estate well becomes clear when the touring party of Elizabeth Bennet and the Gardiners arrives at Pemberley to find grounds that, in accordance with the standards for eighteenth-century British taste in landscape design, seem natural and unpretentious. Such simple elegance was understood to reflect the values and temperament of the owner, as Pope had made clear in his poem on house and grounds aesthetics, the “Epistle to Richard Boyle, Earl of Burlington,” in which he argued against frivolous and impractical estates but applauded the taste in design and architecture of men of sense. It is also quickly apparent that Darcy is a good estate manager because he commands the allegiance and respect of his servants, as Elizabeth and the Gardiners soon learn during their interview with the housekeeper. When, in response to her sister Jane’s question concerning when she first started to love Darcy, Elizabeth quips that “I believe I must date it from my first seeing his beautiful grounds at Pemberley” (p. 361), she is being ironic, but there is a part of her that surely must have been swayed by seeing property that is not only magnificent but graceful. If, in Darcy’s presence, she cannot see past what she takes to be his inexcusable pride, she must recognize during her visit to his well-ordered estate that he is a man of principles and generosity.

While country retirement may have been essential to the life of the worthy gentleman, Austen also offers us a glimpse of the corrupt side of leisure and its symptoms of moral dissolution—luxury and indolence. Despite his good nature, Sir William Lucas demonstrates the affectation of the newly titled in part by abandoning his commercial interests, the success of which had resulted in his public prominence and his knighthood. He is raising a young heir who promises to become as debauched as his father’s fortune will allow, dreaming, as he does already at this tender age, of keeping foxhounds and drinking a daily bottle of wine, should he ever find himself as wealthy as Mr. Darcy. Austen turns her gentle wit on the pretensions of parvenu gentry, but she frowns somewhat more severely upon the shortcomings of the aristocratic matron. Although well established in her rank, Lady Catherine is too easily flattered by Mr. Collins, and her behavior makes it clear that she lacks the genuine good breeding and strength of character of her nephew, Mr. Darcy. Unlike the understated elegance of Darcy’s Pemberley, Lady Catherine’s solemn residence is designed to inspire a discomfiting sense of awe among her visitors. That one of the drawing rooms boasts a “chimney-piece [that] alone had cost eight hundred pounds” (p. 76) serves both to exemplify the ostentation of Rosings Park and to make Mr. Collins’s behavior seem all the more preposterous, for it is he who basks in the reflected glory of his patron’s estate by savoring its every sumptuous detail, including this one.

If leisured society can be extravagant, it can also be lazy. For example, Mr. Bingley’s brother-in-law, Mr. Hurst, “a man of more fashion than fortune” (p. 18), seems entirely incapable of any exertion except eating and playing cards, a fact that Austen humorously establishes as evidence of his perfect lethargy. At Netherfield, when Elizabeth Bennet chooses reading over a game of loo, he is nonplussed. Lacking any interior life himself, Mr. Hurst cannot imagine how one could take pleasure in an activity that is solitary and that might require reflection. Austen’s character sketch reaches its ironic limit when, upon finding the rest of his party unwilling to play cards, Mr. Hurst “had, therefore, nothing to do, but to stretch himself on one of the sofas and go to sleep” (p. 54). In fact, the sorts of leisure activities characters engage in—card playing, dancing, singing, piano playing, walking, conversation, letter writing, reading—may be taken in particular instances to indicate their moral fiber and social inclinations. Generally speaking, the exemplary character is one whose leisure activities imply a willingness to balance private reflection against community-minded sociability. At fault are such characters as Mr. Hurst, whose leisure suggests he lacks a capacity for autonomous thought or action, but also Mary, whose excessive attention to books and piano playing marks an untoward self-absorption.

In contrast, Elizabeth and Darcy are both introspective and fully socialized, even if Darcy refuses to be pleasant to those whom he considers his social inferiors. Both are adept conversationalists, and their verbal sallies display their intelligence, wit, and powers of perception. Elizabeth is also a competent pianist—good enough to entertain company but not so exceptional as to take herself seriously as an artist. Both Elizabeth and Darcy enjoy reading, which should predispose Austen’s audience to like them. But Elizabeth is quick to disown any pretension to being an intellectual, which is the flaw of her sister Mary. By contrast, the unsympathetic Caroline Bingley seems incapable of focusing on a book, and she pretends to enjoy reading only when she believes it will help to impress Mr. Darcy. Mr. Bingley, for whom we feel a measure of affection, does not read either, and we may take this fact as a sign that he lacks the depth of his friend Darcy. Or course, Bingley must be worthy of the heroine’s kind sister and cannot, therefore, be laughable or insipid, like Mr. Hurst; rather, Bingley lacks substance in an amiable, happy-go-lucky way. The characters’ discussion of inclinations toward reading also leads the Netherfield set to render opinions on libraries. Mr. Darcy sees it as an obligation to augment his family’s library collection “in such days as these” (p. 39), an allusion, presumably, to the cultural decay of Britain wrought by the rise of a philistine commercial society that forsakes the liberal arts in favor of market culture. Caroline Bingley, by contrast, sees family libraries as so much grand furniture. No doubt finding the book cover more valuable than the book, she esteems Mr. Darcy’s library for its enhancement of the prestige of the household.

Walking is the other leisure activity that clearly distinguishes Elizabeth Bennet from Caroline Bingley, whose idea of exercise is to gossip as she takes a turn about the drawing room or the shrubbery, and whose exertion is entirely motivated by her romantic interest in Mr. Darcy. Elizabeth enjoys solitary rambles that allow her time for reflection, so it is no hardship when she takes a brisk three-mile walk through fields and over puddles to visit her sister Jane at Netherfield during the latter’s illness. Elizabeth’s fortitude in walking, a consequence of her concern for her sister’s health, has the unintended effect of invigorating the torpid company at Netherfield, if only because her activity seems so brazen to them. Her animation captivates Mr. Darcy and rankles Caroline Bingley, who takes Elizabeth’s brief adventure “to show an abominable sort of conceited independence, a most country-town indifference to decorum” (p. 37). Still, Elizabeth is no romantic heroine of the sort who would be fashioned by Charlotte Brontë several decades later. The sphere of action in Austen’s novel of manners is circumscribed enough so that it would be shocking indeed were Elizabeth, like Brontë’s Jane Eyre, to wander despondently about the English countryside, exhausted and starving. Elizabeth’s own burst of romantic enthusiasm—“What are men to rocks and mountains?” (p. 154)— subsides quickly enough.

If Austen’s attention to the culture of leisure serves to call into question the values of the landed elite even as it reinforces them, the marriage plot complicates the outlook of the novel further still. With respect to social class, the hero and heroine are worlds apart—or so they appear in Darcy’s estimation. At Netherfield, Darcy finds that Elizabeth has “attracted him more than he liked” (p. 60), and he thus resolves to regulate his feelings toward her. Elizabeth’s station in life and the “total want of propriety” (p. 196) among her family members make the match ill-advised, if not untenable, as Darcy callously points out in proposing marriage to her against his better judgment. He is astounded not only that Elizabeth rejects him—in that respect he is no better than Mr. Collins, whose earlier proposal is made with equal confidence in her acceptance—but that his explanation of his initial reluctance has caused offense. That Darcy fails to consider that Elizabeth might actually be offended by a proposal that opens with the suitor’s expression of his disdain for her inferior social connections and his efforts to overcome his love for her suggests that the insuperable gulf he perceives between them seems to him perfectly natural. For her part, Elizabeth knows full well the subtle distinctions that define rank in her society, and it is more his tactlessness than his pointing out an obvious fact of social hierarchy that infuriates her.

It is also the case that Elizabeth has a healthy sense of her own entitlement. As she proudly remarks to Lady Catherine, Mr. Darcy “is a gentleman; I am a gentleman’s daughter; so far we are equal” (p. 331). At Rosings, when Sir William Lucas and his daughter Maria are daunted by the prospect of their encounter with the redoubtable Lady Catherine, we find that Elizabeth, by contrast, “had heard nothing of Lady Catherine that spoke her awful from any extraordinary talents or miraculous virtue, and the mere stateliness of money and rank she thought she could witness without trepidation” (p. 161). In the society of this novel, talent and manners—that is, truly good breeding, rather than affectation—ultimately trump birth and social connections. Even Mr. Darcy endorses this view, as Elizabeth observes. Indeed, when the lovers finally reconcile their differences, Elizabeth teases Darcy that her “impertinence” appeals to him because he is “sick of civility, of deference, of officious attention” (p. 367). Darcy’s ennui, however, should be taken not as a tacit authorization of a new democratic outlook but rather of a meritocratic one. That is, the values of the gentry and the aristocracy are reinforced even as their membership becomes infused with the blood of the professional classes, which would seem to undermine the restrictive claims upon which the upper classes predicate their existence. The possibility that Mr. Darcy might marry his frail cousin, Miss Anne de Bourgh, in order to consolidate their estates is presented as an outmoded aristocratic notion, not to be taken seriously by the new generation.

What makes the lovers’ attitudes possible is that the real consequences of social rank are diminished by the conventions of romantic comedy. A typical feature of the comic novel is that powerful social distinctions upheld in everyday life tend to be suspended in an effort to further the plot. Within the safe space of the novel, such comic upheavals create exciting possibilities for minor social transgressions; at the same time, in the novel’s conclusion, the existing order becomes reaffirmed. In this case, the reaffirmation happens as Elizabeth becomes absorbed into Darcy’s world. It is standard comic fare that the potentially formidable member of the ruling class who might prevent the budding romance— here, Lady Catherine—turns out to be a relatively powerless busybody who depends on weak-minded followers to reinforce her sense of her own importance. Lady Catherine, in fact, resembles the stock type of aging woman tenaciously clinging to her diminished power, a familiar character found in Restoration comic drama, as well as in the mid-eighteenth- century novels of Henry Fielding and Samuel Richardson.

Whatever its social and comic implications, the marriage plot is the chief concern throughout the novel, and there is a sense of urgency about forging the right unions that motivates the action of the entire book. The ironic opening gambit—“It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife”—rehearses the epigrammatic wisdom of a gossip-driven community comprising women like Mrs. Bennet, who is herself eager to enhance the prestige of her family by marrying her daughters well. Prestige and social connection, however, are not the only motivating forces in this neighborhood or within the Bennet household. In the idealistic world of the romantic comedy, Mrs. Bennet’s ambition to see her daughters nicely settled appears a simple matter of crude one-upmanship with Lady Lucas. Thus, when Mr. Bennet teases his wife rather unkindly over her preoccupation with finding eligible suitors, the reader is amused. We forget, though, that Mr. Bennet’s own first question about the newly arrived Mr. Bingley concerns his marital status, which suggests either that Mr. Bennet is baiting his wife or that his apparent indifference on the matter is feigned. Mr. Bennet, of course, should be concerned about the marriage question. As the narrator informs us later, he regrets having spent all his disposable income, instead of reserving a portion of it to protect his daughters’ financial future. It hardly excuses him that he had assumed he would have a son whose coming-of-age would nullify the “entail”—that is, the legal document that places restrictions on who may inherit his estate. (In the absence of male heirs, women could typically inherit an estate but not if an entail existed barring them from doing so.) As endearing a character as Mr. Bennet is, he has not behaved responsibly as a father, a fact that becomes all the more apparent when Lydia, who has had very little in the way of sensible parental guidance, elopes with Wickham, thereby, as Lady Catherine observes, jeopardizing the marriage prospects of her four sisters in a world that still cares about the taint of family reputation: “Not Lydia only, but all were concerned in it” (p. 272).

Mrs. Bennet does not seem such a buffoon when we consider that her daughters really will be in dire straits should they not marry. The entail of the Bennet estate to Mr. Collins guarantees not only that the house and grounds will no longer be available to the Bennet women but that their yearly income will be considerably reduced. In fact, without one sister well established in marriage before the death of Mr. Bennet, it would be difficult for any of the five to maintain the condition of a gentlewoman at all. Having one sister comfortably married, however, could create a measure of financial security for the others and might help, through the social connections established, to ensure a succession of respectable marriages in the family. The possibility that, in lieu of marriage, these young women might become governesses and thereby preserve a tenuous connection to the gentry is simply not a viable option in this novel, where working for a living, even in relatively genteel circumstances, is a fate worse than marriage to Mr. Collins. If we put aside the romantic ideal of the novel and look at the material reality, Mrs. Bennet’s frustration with Elizabeth for declining Mr. Collins’s proposal is entirely reasonable: Had Elizabeth accepted her distant cousin’s hand, she could have preserved her father’s estate for herself and for her unmarried sisters.

Nor, for that matter, does the other ostensibly foolish character of the novel, Mr. Collins himself, seem so oblivious in refusing to acknowledge Elizabeth’s rejection of his proposal. He may be pompous, but he is also practical, and he knows minutely the details of Elizabeth’s meager future inheritance. The idea that she might turn him down is simply inconceivable to him, for, as he rightly points out, given her family circumstances, she may never receive another offer. That she declines Mr. Darcy’s first proposal, is, in practical terms, even more astonishing. Remaining single after her parents’ deaths might mean an annual income of £40 (4 percent annual interest, as Mr. Collins estimates it, on a £1,000 share of her mother’s legacy), a portion of which would go toward renting a room somewhere in the village. Marriage to Mr. Darcy, by stark contrast, would mean having at her disposal a reputed £10,000 annually, plus the amenities of Pemberley, the house in London, the carriages, the servants, and so forth. It is difficult to convert these sums into the modern British pound or American dollar, in part thanks to inflation but mostly because the nineteenth-century economy and culture are so very different from ours, but suffice it to say that Elizabeth, in declining Mr. Darcy, has rejected fantastic wealth for the likelihood of a quite modest existence, far beneath that to which she has become accustomed.

The conventions of romantic comedy, however, do not allow us to focus on the folly of Elizabeth’s decision to follow her heart and her principles or to dwell for very long on the grim financial future of these five unwed women. The narrator, in fact, offers no sustained commentary on how limited the options are for women in this society. The only real defenses of women’s moral and legal entitlement to inherit property fall from the lips of the two caricatural aging women: Mrs. Bennet, who refuses to recognize the legality of the entail that will disinherit herself and her daughters, and Lady Catherine, who opines, “I see no occasion for entailing estates from the female line” (p. 164). The romantic narrative would also lead us to believe that Elizabeth should indeed be true to herself, for there is something terribly dull about the financially “prudent” marriage, and something disgraceful about the “mercenary” one, although the two motives amount to the same thing, as Elizabeth explains to Mrs. Gardiner (p. 153). The prospect of repudiating the desire for romance and settling for “a comfortable home,” as Charlotte Lucas has done (p. 125), is represented to be a fairly dismal choice, which is one reason why the novel looks so very different from the conservative morality tales that were popular in this period. Austen’s narrator tends to see the world from Elizabeth Bennet’s perspective, and so, therefore, do we, and the plot reconciliation confirms the legitimacy of this view. When the two elder Bennet sisters finally become engaged, we know that Elizabeth’s match is better than Jane’s, not because Darcy is the master of Pemberley and has twice the annual income of Bingley, but because, as Elizabeth compares the two sisters’ relative happiness, “she only smiles, I laugh” (p. 369).

That this resolution glosses over Elizabeth’s early attraction to Wickham, who is now married to her thoughtless sister Lydia, and her prior antipathy toward Darcy—a dislike so pronounced that Jane can hardly accept her sister’s subsequent avowal of love for him—is not altogether justified by Elizabeth’s recent maturity or by the evidence that comes to light about Wickham’s and Darcy’s respective characters. At the very least, Elizabeth’s change of heart suggests that she is far more rational in romantic matters than one might think the passionate and idealistic side of her nature would allow. But it is the role of the comic ending to obscure inappropriate desires and inconvenient hostilities in order to establish the alliances that will secure a stable and joyous future. What distinguishes the conclusion of Austen’s great novel from that of lesser comic fare is that, as we turn the final pages, the new community established at Pemberley and at the nearby Bingley estate, by the characters we have come to know so well, seems to us both plausible and reassuring.