13

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- “Look through” and “look at” texts. (GEO 1; SLO 3)

- Use seven strategies for analyzing and responding to texts at a deeper level. (GEO 1; SLO 3)

- Use critical reading to strengthen your writing. (GEO 1, 2; SLO 3)

Critical reading means analyzing a text closely through cultural, ethical, and political perspectives. Reading this way means adopting an inquiring and even skeptical stance toward the text, allowing you to explore insights that go beyond its apparent meaning.

When you read critically, you aren’t discovering the so-called “hidden” or “real” meaning of a text. In reality, a text’s meaning is rarely hidden, but it’s also not always obvious. As a critical reader, your job is to read texts closely and think about them analytically so you can better understand their cultural, ethical, and political significance. When reading a text critically, you are going deeper, doing things like:

- asking insightful and challenging questions

- figuring out why people believe some things and are skeptical of others

- evaluating the reasoning, authority, and emotion in the text

- contextualizing the text culturally, ethically, and politically

- analyzing the text based on your own values and beliefs

Critical reading is also a key component of good writing. In college courses and in your career, you will be working with new and unfamiliar kinds of texts while interpreting images, films, and experiences. In this chapter, you will learn a variety of critical reading strategies that will help you better understand words and images at a deeper level. You will learn strategies for analytical thinking, helping you look beyond the surface meaning of texts to gain a critical understanding of what their authors are saying and how they are trying to influence their readers.

Looking Through and Looking At a Text

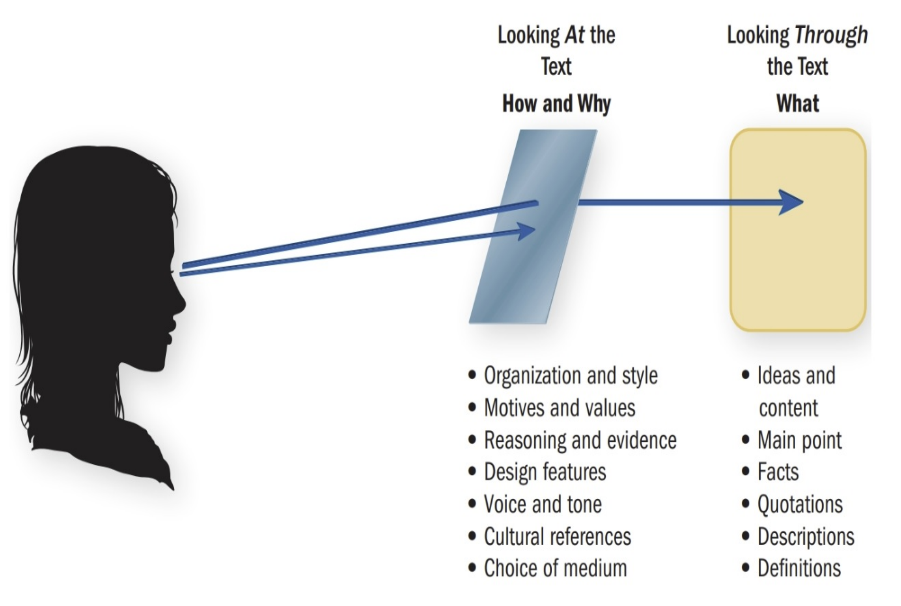

When reading critically, you should think of yourself as interpreting the text in two different ways: looking through and looking at.

Looking Through a Text

Most of the time, you are looking through a text, reading the words and viewing the images to figure out what the author is saying. You are primarily paying attention to what it says, not how it says it—to the content of each text, not its organization, style, or medium. Your goal is to understand the text’s main points while gathering the information it provides.

Looking At a Text

Other times, you are looking at a text, exploring why the author or authors made particular choices:

- Genre: choice of genre, including decisions about content, organization, style, design, and medium.

- Persuasion strategies: uses of reasoning, appeals to authority, and appeals to emotion.

- Style and diction: uses of specific words and phrasing, including metaphors, irony, specialized terms, sayings, profanity, or slang.

Reading critically is a process of toggling back and forth between “looking through” and “looking at” to understand both what a text says and why it says it that way (Figure 13.1). This back-and-forth process will help you analyze the author’s underlying motives and values. You can then better understand the cultural, ethical, and political influences that shaped the writing of the text.

Reading Critically: Seven Strategies

The key to critical reading is to read actively. Imagine that you and the author are having a conversation. You should take in what the author is saying, but you also need to respond to the author’s ideas.

While you read, be constantly aware of how you are reacting to the author’s ideas.

Do you agree with these ideas? Do you find them surprising, new, or interesting? Are they mundane, outdated, or unrealistic? Do they make you angry, happy, skeptical, or persuaded? Does the author offer ideas, arguments, or evidence you can use in your own writing? What information in this text isn’t useful to you?

Strategy 1: Preview the Text

When you start reading a text, give yourself a few moments to size it up. Ask yourself some basic questions:

- What are the major features of this text? Scan and skim through the text to gather a sense of the text’s topic and main point. Pay special attention to the following features:

- Title and subtitle—make guesses about the text’s purpose and main point based on the words in the title and subtitle.

- Author—look up the author or authors on the Internet to better understand their expertise in the area as well as their values and potential biases.

- Chapters and headings—scan the text’s chapter titles, headings, and subheadings to figure out its organization and major sections.

- Visuals—browse any graphs, charts, photographs, drawings, and other images to gain an overall sense of the text’s topic.

- What is the purpose of this text? Find the place where the author or authors explain why they wrote the text. In a book, the authors will often use the preface to explain their purpose and what motivated them to write. In texts such as articles or reports, the authors will usually signal what they are trying to accomplish in the introduction or conclusion.

- What is the genre of the text? Identify the genre of the text by analyzing its content, organization, style, and design. What do you normally expect from this genre? Is it the appropriate genre to achieve the authors’ purpose? For this genre, what choices about content, organization, style, design, and medium would you expect to find?

- What is your first response? Pay attention to your initial reactions to the text. What seems to be grabbing your attention? What seems new and interesting? What doesn’t seem new or interesting? Based on your first impression, do you think you will agree or disagree with the authors? Do you think the material will be challenging or easy to understand?

Strategy 2: Play the Believing and Doubting Game

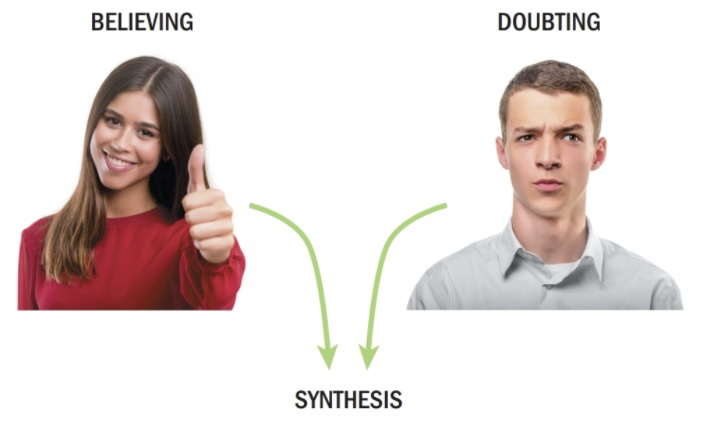

Peter Elbow, a scholar of rhetoric and writing, invented a close reading strategy called the “Believing and Doubting Game” that will help you analyze a text from different points of view.

The Believing Game: Imagine you are someone who believes (1) what the author says is completely sound, interesting, and important, and (2) how the author has expressed these ideas is amazing or brilliant. You want to play the role of someone who is completely taken in by the argument in the text, whether you personally agree with it or not.

The Doubting Game: Now pretend you are a harsh critic, someone who is deeply skeptical or even negative about the author’s main points and methods for expressing them. Search out and highlight the argument’s factual shortcomings and logical flaws. Look for ideas and assumptions that a skeptical reader would reject. Repeatedly ask, “So what?” or “Who cares?” or “Why would the author do that?” as you read and re-read.

Once you have studied the text from the perspectives of a “believer” and a “doubter,” you can then create a synthesis of both perspectives that will help you develop your own personal response to the text (Figure 13.2). More than likely, you won’t absolutely believe or absolutely reject the author’s argument. Instead, your synthesis will be somewhere between these two extremes.

Playing the Believing and Doubting Game allows you to see a text from completely opposite perspectives. Then you can come up with a synthesis that combines the best aspects of each point of view.

Elbow’s term, “game,” is a good choice for this kind of critical reading.

You are role-playing with the argument, first analyzing it in a sympathetic way and then scrutinizing it in a skeptical way. This two-sided approach will help you not only better understand the text but also figure out what you believe and why you believe it.

Strategy 3: Annotate the Text

As you read the text, highlight important sentences and take notes on the items you find useful or interesting.

- Highlight and annotate. While reading, keep a pencil or pen in your hand. If you are reading onscreen, you can use the “review” or “comment” feature of your word processor or e-reader to highlight parts of the text and add comments. These highlights and notes will help you find and examine key passages later on.

- Take notes. Write your observations and reactions to the text in your notebook or in a separate document on your computer. As you take notes, remember to look through and look at the text.

- Looking through: Describe what the text says, summarizing its main claims, facts, and ideas.

- Looking at: Describe how the author is using various rhetorical techniques, such as style, organization, design, medium, and so forth to make the argument.

You might find it helpful to use a notetaking app such as Evernote, Google Keep, Memonic, OneNote, or Marky (Figure 13.3). With these tools, your notes are stored in the cloud, allowing you to access your comments whenever you are online. These electronic notetaking tools are especially helpful for organizing your sources and keeping track of your ideas.

Strategy 4: Analyze the Proofs in the Text

Almost all texts are argumentative in some way because most authors are directly or indirectly making claims they want you to believe. These claims are based on proofs that the author wants you to accept. Even if you agree with the author, you should challenge those claims and proofs to see if they make sense and are properly supported. Arguments tend to use three kinds of proofs: appeals to reason, appeals to authority, and appeals to emotion. Rhetoricians often refer to these proofs by their ancient Greek terms: logos (reason), ethos (authority), and pathos (emotion).

- Reasoning (logos): Analyze the author’s use of logical statements and examples to support their arguments. Logical statements use patterns like: if x then y; either x or y; x causes y; the benefits of x are worth the costs y; and x is better than y. The use of examples is another kind of reasoning. Authors will often use examples to describe real or hypothetical situations by referring to personal experiences, historical anecdotes, demonstrations, or well-known stories.

- Authority (ethos): Look at the ways the author draws on her or his own authority or the authority of others. The author may appeal to specific credentials, personal experiences, moral character, the expertise of others, or a desire to do what is best for the readers or others.

- Emotion (pathos): Pay special attention to the author ’s attempts to use emotions to sway your opinion. He or she may promise emotionally driven things that people want, such as happiness, fun, trust, money, time, love, reputation, popularity, health, beauty, or convenience. Or the author may use emotions to make readers uncomfortable, implying that they may become unhappy, bored, insecure, impoverished, stressed out, ignored, disliked, unhealthy, unattractive, or overworked.

Almost all texts use a combination of logos, ethos, and pathos. Advertising, of course, relies heavily on pathos, but ads also use logos and ethos to persuade through reasoning and credibility. Scientific texts, meanwhile, are dominated by logos, but occasionally scientists draw upon their reputation (ethos) and they will use emotion (pathos) to add emphasis and color to their arguments. You can turn to Chapter 16: Argumentative Strategies, for a more detailed discussion of these three forms of proof.

Strategy 5: Contextualize the Text

All authors are influenced by the cultural, ethical, and political events that were happening around them when they were writing the text. To better understand these contextual influences, look back at what was happening while the text was being written.

- Cultural context. Do some research on the culture in which the author lived while writing the text. What do people from this culture value? What kinds of struggles did they face or are they facing now? How do people from this culture see the world similarly to or differently from the way you do? How is this culture different from your culture?

- Ethical context. Look for places in the text where the author is concerned about rights, legalities, fairness, and sustainability. Specifically, how is the author responding to abuses of rights or laws? Where does the author believe people are being treated unfairly or unequally? Where does he or she believe the environment is being handled wastefully or in an unsustainable way? How might the author’s sense of ethics differ from your own?

- Political context. Consider the political tensions and conflicts that were happening when the author wrote the text. Was the author trying to encourage political change or feeling threatened by it? In what ways were political shifts changing people’s lives at the time? Was violence happening, or was it possible? Who were the political leaders of the time, and what were their desires and values?

Strategy 6: Analyze Your Own Assumptions and Beliefs

Examining your own assumptions and beliefs is probably the toughest part of critical reading. No matter how unbiased or impartial we try to be, all of us still rely on our own pre-existing assumptions and beliefs to decide whether or not we agree with the text. Here are a few questions you can ask yourself after reading:

- How did my first reaction influence my overall interpretation of the text?

- How did my personal beliefs influence how I interpreted and reacted to the author’s claims and proofs?

- How did my personal values cause me to react favorably to some parts of the text and unfavorably to other parts?

- Why exactly was I pleased with or irritated by some parts of this text?

- Have my views changed now that I have finished reading and analyzing the text?

If an author’s text challenges your assumptions and beliefs, that’s a good thing. As an author yourself, you too will be trying to challenge, influence, inform, and entertain your readers. Treat other authors and their ideas with the same respect and open-mindedness that you would like from your own readers.

Even if you leave the critical reading process without substantially changing your views, you will come away from the experience stronger and better able to understand and explain what you believe and why you believe it.

Strategy 7: Respond to the Text

Now it’s time to take stock and respond to the text. Ask yourself these questions, which mirror the ones you asked during the pre-reading phase.

- Was your initial response to the text accurate? In what ways did the text meet your original expectations? Where did you find yourself agreeing or disagreeing with the author? In what ways did the author grab your attention? Which parts of the text were confusing, requiring a second look? Were you pleased with the text, or were you disappointed?

- How does this text meet your own purposes? In what ways did the author’s purpose line up with the project you are working on? How can you use this material to do your own research and write your own paper? How did the author’s ideas conflict with what you need to achieve?

- How well did the text follow the genre? After reading the text, do you feel that the author met the expectations of the genre? Where did the text stray from the genre or stretch it in new ways? Where did the text disrupt your expectations for this genre?

- How should you re-read the text? What parts of the text need to be read more closely? In these places, re-read the content carefully, paying attention to what it says and looking for ideas such as key concepts or evidence that needs clarification.

Using Critical Reading to Strengthen Your Writing

Critical reading will be important throughout your time at college and your career. This kind of close reading is most important, though, when you are developing your own projects. It will help you write smarter, whether you are writing for a college course, your job, or just for fun. Here are some strategies for converting your critical reading into informative and persuasive writing.

Responding to a Text: Evaluating What Others Have Written

When responding to a text, you should do more than decide whether you “agree” or “disagree.” All sides will have some merit—otherwise, the topic would not be worth discussing. So you need to explain your response and where your views align with or diverge from the author’s views. Ask yourself these questions to help develop a complete, accurate, and fair response.

- Why should people care about what the author has written? Explain why you think people should care about the issue and why.

__________ is an important issue because __________.

While __________ might not seem important at first glance, it has several important consequences, such as __________, __________, and __________.

Example

2. Where and why do you find the author’s views compelling—or not? Describe exactly where and why you agree or disagree with an author’s conclusions or viewpoints.

At the heart of this debate is a disagreement about the nature of __________, whether it was __________ or __________.

While __________ contends that there are two and only two possibilities, I believe we should consider other possibilities, such as __________ or __________.

Admittedly, my negative reaction to __________’s assertion that __________ was influenced by my own beliefs that __________ should be __________.

Example

Responding with a Text’s Positions, Terms, and Ideas: Using What Others Have Written

You can now respond to the text by incorporating what the author has said into your writing. Joseph Harris offers a useful system of four “moves” for using what others have said to advance your own ideas and arguments.

1. Illustrating. Use facts, images, examples, descriptions, or stories provided by an author to illustrate and explain your own views.

As __________ summarizes the data on __________, there are three major undisputed facts: first, __________; second, __________; and third, __________.

This problem is illustrated well by the example offered by __________, who explains that __________.

Example

2. Authorizing. Use the authority, expertise, or experience of the author to strengthen your own position or to back up a point you want to make without going into a lengthy explanation.

As explained by __________, a recognized authority on the subject of __________, the most important features of a __________ are __________ and __________.

Although __________ makes a valid point in arguing that __________, a more balanced and workable solution is offered by __________, who suggests we __________.

Example

3. Borrowing. Borrow a term, definition, or idea developed by the author for thinking about the issue you’re writing about.

__________ defines __________ as “__________.” __________’s concept of “__________” is helpful for thinking through the complexities of this issue.

Example

4. Extending. Extend the author’s ideas in a new direction or apply them to topics and situations that the author did not consider.

The successful model described by __________ could be implemented here with some modification, including __________, __________, and __________.

While I generally agree with __________’s recommendations on this issue, I suggest they do not go far enough.

For example, __________.

Example

These four moves—illustrating, authorizing, borrowing, and extending—will help you become part of the larger conversation about your topic. By incorporating the ideas of others into your own work, you can support your own ideas while helping your readers understand where your ideas agree or contrast with the ideas of others.

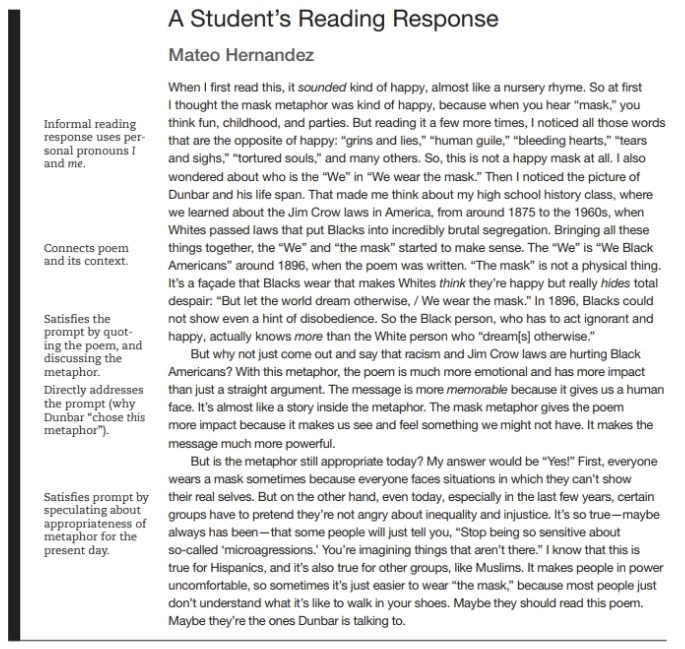

The Reading Response

In many of your college courses in every discipline, your professor may assign a reading response as “informal writing.” A literature professor might ask you to write about your first reaction to a poem to help you explore its meaning. An anthropology professor might ask you to describe your reactions to the rituals of a different culture. In the workplace, trainers and consultants often use informal writing exercises to help teams of employees explore ideas together—a kind of brainstorming. Your professors may assign a wide variety of reading response assignments, but no matter what the specific assignment is, make sure you do the following:

Read the prompt carefully. Make sure you understand exactly what your professor wants you to do. Pay attention to the verbs. Are you supposed to summarize, explore, speculate, analyze, identify, explain, define, evaluate, apply, or something else?

Try out new ideas and approaches. Informal writing can be your chance to speculate, explore, and be creative. Be sure you understand and deliver what your professor expects, but be aware that reading responses can also provide opportunities to stretch your thinking into new areas.

Show that you have read, can understand, and can work with the material. Ground your response in the material you are being asked to discuss. When writing about a story or poem, come back to the text and provide quotes, summaries, and descriptions. If the reading involves a concept, make sure your response shows that you understand or can use the concept to address the prompt.

Branch out and make connections (if appropriate). Look for the broader implications and for connections with other issues from the course. With informal writing like reading responses, you’re usually allowed or even encouraged to take risks and speculate. If you’re not sure whether your professor wants you to do this, ask.

Reading Response Assignment

Here is an example of the kind of response prompt you might be assigned in a literature class. This prompt is about a poem written in 1896 by the African American writer Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872–1906). The professor’s prompt follows the poem; the student’s response is next.

We Wear the Mask (1896) by Paul Laurence Dunbar

We wear the mask that grins and lies,

It hides our cheeks and shades our eyes,—

This debt we pay to human guile;

With torn and bleeding hearts we smile,

And mouth with myriad subtleties.

Why should the world be over-wise,

In counting all our tears and sighs?

Nay, let them only see us, while

We wear the mask.

We smile, but, O great Christ, our cries

To thee from tortured souls arise.

We sing, but oh the clay is vile

Beneath our feet, and long the mile;

But let the world dream otherwise,

We wear the mask!

Reading Response Prompt for “We Wear the Mask”

Write a response paper that is at least 400 words long and that incorporates at least two quotations from the poem. Paul Laurence Dunbar’s poem renders a general social issue concrete and tangible with his central metaphor of “the mask.” Examine this metaphor closely. Explain how it works in the poem and how it adds to the impact or meaning of the poem in terms of tone, theme, or overall message. Finally, speculate about whether you believe the metaphor is still appropriate in today’s world, even though the poem was written over 100 years ago.

A form of language analysis that does not take the given text at face value, but involves a deeper examination of the claims put forth as well as the supporting points and possible counterarguments.

A category of artistic composition, as in music or literature, characterized by similarities in form, style, or subject matter.

The action or fact of persuading someone or of being persuaded to do or believe something. See also "rhetoric."

The manner of expressing thought in language characteristic of an individual, period, school, or nation.

Word choice; a writer's or speaker's distinctive vocabulary choices and style of expression.

A rhetorical appeal to logic, reason, and common sense.

A rhetorical appeal to authority, credibility, and character.

A rhetorical appeal to emotion.