6

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Support your thesis in the body of your paper. (GEO 2; SLO 1, 2)

- Write a paragraph with an effective topic sentence and support. (GEO 2; SLO 1, 2)

- Get paragraphs to flow from one sentence to the next. (GEO 2; SLO 1)

The body of your paper will give readers the information you promised in the introduction. In other words, you are now “telling them.” To draft this part of the paper, you want to carve up the body into two to five topics that you will discuss. A shorter paper will usually devote one or two paragraphs per topic, while a longer paper will often devote an entire section to each topic.

Drafting the body can be difficult and even frustrating. Freewriting is usually a good way to get the words flowing. Just write down everything that comes to mind without stopping. With some text on the screen, you can then revise the sentences, move them around, and collect them into paragraphs. Also, don’t hesitate to go back and use those invention strategies you learned about in Chapter 1: Getting Started. Even though you are in the drafting phase, you can always create another concept map or do more brainstorming to generate fresh ideas. You can also use heuristics or your five senses to explore new pathways or figure out new ways to describe things. The drafting phase will trigger many new ideas and issues that you didn’t expect. Don’t ignore those pesky thoughts! Use them to be creative! That’s your brain doing its job.

Paragraphs divide your papers into building blocks of ideas that help your readers quickly understand how you have organized your text. They also help your readers figure out your main points and how you are supporting them. A paragraph’s job is rather straightforward: A paragraph presents an idea or claim and then supports it with examples, data, facts, reasoning, anecdotes, quotations, or descriptions. A paragraph isn’t just a bunch of sentences that seem to fit together. Instead, a solid paragraph works as a single unit that is built around a central topic, idea, issue, or question. A section is a group of paragraphs that supports a larger idea or claim. A section offers a broad claim followed by a series of supporting paragraphs. Longer college-length papers and workplace documents are typically carved up into several sections to make them easier to read. In this chapter, you will learn how to develop smooth-flowing paragraphs and sections.

Creating a Basic Paragraph

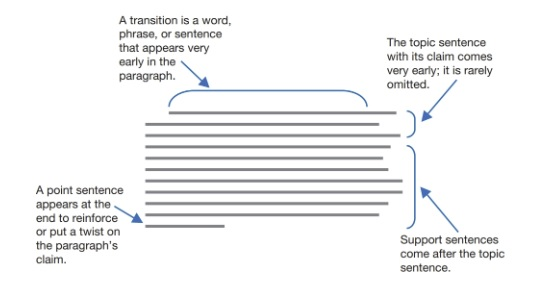

Paragraphs usually include up to four kinds of sentences: a transition sentence, a topic sentence, support sentences, and a point sentence. The diagram in Figure 21.1 shows where these kinds of sentences usually appear in any given paragraph. Here is a typical paragraph with these four elements noted.

Body Paragraph of “Hip Hop Generation” by Bakari Kitwana

Transition or Transitional Sentence (Optional)

The purpose of a transition or transitional sentence is to make a smooth bridge from the prior paragraph to the current paragraph. Transitions signal to readers how two paragraphs are related or alert them to a shift in direction. A transition, if needed, should appear near the beginning of the paragraph. It might be a complete sentence placed at the start of a paragraph, or it might be a single word or phrase placed at the start of the topic sentence (e.g. finally, in the past). A transitional sentence might ask a question or signal a turn in the discussion:

Example

A question like this one sets up the topic sentence, which usually follows immediately. Here is a transitional sentence that signals a turn in the discussion:

Example

A transitional sentence often redirects the readers’ attention to a new issue while setting up the paragraph’s claim (topic sentence). A transitional word or phrase can also make an effective bridge between two paragraphs. Here are some transitional words and phrases that you can try out:

| Accordingly | In any event | Nevertheless |

| As a result | In conclusion | Of course |

| As an illustration | In other words | On the contrary |

| Besides | In the future | On the whole |

| Consequently | In the past | Specifically |

| Equally important | Likewise | The next step |

| For example | Meanwhile | To illustrate |

| For this reason | More specifically | To summarize |

Topic Sentence (Needed)

A topic sentence announces the paragraph’s subject and makes a statement or claim that the rest of the paragraph will support or prove.

Examples

At the beginning of his presidency, Ronald Reagan struggled with a number of pressing economic issues (statement).

A good first step would be to reduce the number of required courses in general education (claim).

Debt on credit cards is the greatest threat to the American family’s financial security (claim).

The topic sentence will be the first or second sentence in most paragraphs. You have probably been told that a topic sentence can be put anywhere in a paragraph. That’s generally true, but you should put the topic sentence early in the paragraph if you want your readers to understand the paragraph’s subject and be able to identify its key statement or claim quickly. Putting the topic sentence in the middle or at the end of a paragraph makes your main ideas harder to find.

Of course, any guideline has exceptions. For example, if you are telling your readers a story or leading them toward a controversial or surprising point, your topic sentence might be better placed at the end of the paragraph.

Support Sentences (Needed)

Support sentences will make up the body of your paragraphs. These sentences back up the paragraph’s topic sentence with examples, details, reasoning, facts, data, quotations, anecdotes, definitions, descriptions, and anything else needed to provide support. Support sentences usually appear after the topic sentence.

Example

Point Sentence (Optional)

Point sentences state, restate, or amplify the paragraph’s main point at the end of the paragraph. A point sentence is especially useful in longer paragraphs when you want to reinforce or restate the paragraph’s topic sentence in different words.

Example

As shown in the paragraph above, a point sentence is a good way to stress the point of a complex paragraph. The topic sentence at the beginning of the paragraph states a claim and the point sentence drives it home.

How to Write a Body Paragraph

Let’s walk through a 5-step process to building a paragraph. Each step of the process will include an explanation of the step and a bit of “model” text to illustrate how the step works. Our finished model paragraph will be about slave spirituals, the original songs that African Americans created during slavery. The model paragraph uses illustration (giving examples) to prove its point.

Step 1. Decide on a controlling idea and create a topic sentence.

Paragraph development begins with the formulation of the controlling idea. This idea directs the paragraph’s development. Often, the controlling idea of a paragraph will appear in the form of a topic sentence. In some cases, you may need more than one sentence to express a paragraph’s controlling idea. Here is the controlling idea for our “model paragraph,” expressed in a topic sentence:

Example

Step 2. Explain the controlling idea.

Paragraph development continues with an expression of the rationale or the explanation that the writer gives for how the reader should interpret the information presented in the idea statement or topic sentence of the paragraph. The writer explains his/her thinking about the main topic, idea, or focus of the paragraph. Here’s the sentence that would follow the controlling idea about slave spirituals:

Example

Step 3. Give an example (or multiple examples).

Paragraph development progresses with the expression of some type of support or evidence for the idea and the explanation that came before it. The example serves as a sign or representation of the relationship established in the idea and explanation portions of the paragraph. Here are two examples that we could use to illustrate the double meanings in slave spirituals:

Examples

For example, according to Frederick Douglass, the song “O Canaan, Sweet Canaan” spoke of slaves’ longing for heaven, but it also expressed their desire to escape to the North. Careful listeners heard this second meaning in the following lyrics: “I don’t expect to stay / Much longer here. / Run to Jesus, shun the danger. / I don’t expect to stay.”

Slaves even used songs like “Steal Away to Jesus (at midnight)” to announce to other slaves the time and place of secret, forbidden meetings.

Step 4. Explain the example(s).

The next movement in paragraph development is an explanation of each example and its relevance to the topic sentence and rationale that were stated at the beginning of the paragraph. This explanation shows readers why you chose to use this/or these particular examples as evidence to support the major claim, or focus, in your paragraph.

Continue the pattern of giving examples and explaining them until all points/examples that the writer deems necessary have been made and explained. NONE of your examples should be left unexplained. You might be able to explain the relationship between the example and the topic sentence in the same sentence which introduced the example. More often, however, you will need to explain that relationship in a separate sentence. Look at these explanations for the two examples in the slave spirituals paragraph:

Example

Step 5. Complete the paragraph’s idea or transition into the next paragraph.

The final movement in paragraph development involves tying up the loose ends of the paragraph and reminding the reader of the relevance of the information in this paragraph to the main or controlling idea of the paper. At this point, you can remind your reader about the relevance of the information that you just discussed in the paragraph. You might feel more comfortable, however, simply transitioning your reader to the next development in the next paragraph. Here’s an example of a sentence that completes the slave spirituals paragraph:

Example

Notice that the example and explanation steps of this 5-step process (steps 3 and 4) can be repeated as needed. The idea is that you continue to use this pattern until you have completely developed the main idea of the paragraph.

Here is a look at the completed “model” paragraph:

Example

The Key to the “Perfect” Paragraph

Paragraphs are in “essence—a form of punctuation, and like other forms of punctuation they are meant to make written material easy to read.” – Michael Harvey

Effective paragraphs are the fundamental units of academic writing; consequently, the thoughtful, multifaceted arguments that your professors expect depend on them. Without good paragraphs, you simply cannot clearly convey sequential points and their relationships to one another.

Many novice writers tend to make a sharp distinction between content and style, thinking that a paper can be strong in one and weak in the other, but focusing on organization shows how content and style converge in deliberative academic writing. Your professors will view even the most elegant prose as rambling and tedious if there isn’t a careful, coherent argument to give the text meaning. Paragraphs are the “stuff” of academic writing and, thus, worth our attention here.

To reiterate the initial point, it is useful to think of paragraphs as punctuation that organize your ideas in a readable way. Each paragraph should be an irreplaceable node within a coherent sequence of logic. Thinking of paragraphs as “building blocks” evokes the “five-paragraph theme” structure explained earlier: if you have identical stone blocks, it hardly matters what order they’re in. In the successful organically structured college paper, the structure and tone of each paragraph reflect its indispensable role within the overall piece. Make every bit count and have each part situated within the whole.

Getting Paragraphs to Flow (Cohesion)

Getting your paragraphs to flow is not difficult, but it takes a little practice. Flow, or cohesion, is best achieved by paying attention to how each paragraph’s sentences are woven together. You can use two techniques, subject alignment and given-new chaining, to achieve this feeling of flow.

Subject Alignment in Paragraphs

A well-written paragraph keeps the readers’ focus on the central subject, idea, issue, or question. For example, the following paragraph does not flow well because the subjects of the sentences are inconsistent:

Example

You can get a paragraph to flow by aligning the paragraph’s sentences around a common set of subjects.

Example

This paragraph flows better (it is coherent) because the subjects of the sentences are all people. The paragraph is about the people at the park, so making people the subjects of the sentences creates the feeling that the paragraph is flowing.

Given-New in Paragraphs

Another good way to create flow is to use something called “given-new chaining” to weave together the sentences in a paragraph. Here’s how it works. Each sentence starts with something that appeared in a prior sentence (called the “given”). Then the remainder of the sentence offers something that the readers didn’t see in the prior sentence (called the “new”).

Example

In this paragraph, the beginning of each sentence takes something from the previous sentence or an earlier sentence and then adds something new. This creates a given-new chain, causing the text to feel coherent and flowing. A combination of subject alignment and given-new chaining will allow you to create good flow in your paragraphs.

The majority of an essay in which claims are presented and subsequently proven, described, analyzed, or explained.

A discovery tool that helps you ask insightful questions or follow a specific pattern of thinking.

A self-contained unit of discourse in writing dealing with a particular point or idea.

A word, phrase, or sentence that shows the relationship between paragraphs or sections of a text or speech. Transitions provide greater cohesion by making it more explicit or signaling how ideas relate to one another. Transitions are bridges that carry a reader from section to section.

The majority of a paragraph, support sentences back up the main point or claim.

A rhetorical appeal to logic, reason, and common sense.

A piece of informatin that is known or proven to be true.

Facts and statistics collected together for reference or analysis.

A group of words taken from a text or speech and repeated by someone other than the original author or speaker, noted with quotation marks.

A short, personal story about the writer's own experiences.

A statement of the exact meaning of a word or idea.

A pattern of narrative development that aims to make vivid a place, object, character, or group.

Sentences at the end of a paragraph that restate or amplify the paragraph's main point or claim.

The grammatical and lexical linking within a text or sentence that holds a text together and gives it meaning (also called "flow").

Related to "cohesive"