9

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Develop and narrow your topic to respond to any writing situation. (GEO 2; SLO 1, 4)

- Develop your angle, the unique perspective you’ll bring to the topic. (GEO 2; SLO 4)

- How to profile your readers to understand their needs, values, and attitudes. (GEO 2; SLO 4)

- How to figure out how context—where readers read and the mediums they use—shapes your readers’ experience. (GEO 2; SLO 4)

- Identify your purpose, or what you want to accomplish. (GEO 2; SLO 4)

- Use your identified purpose to develop a thesis sentence (or main point). (GEO 2; SLO 1. 4)

- Choose the appropriate genre for your purpose. (GEO 2; SLO 4)

One of your professors just handed you a new writing assignment. What should you do first? Take a deep breath. Then, read the assignment closely and ask yourself a few specific questions about what you need to do:

- What am I being asked to write about? (Topic)

- What is new or has changed recently about this topic? (Angle)

- Where and when will they be reading this document? (Context)

- Who will read this document, and what do they expect? (Audience)

- What exactly is the assignment asking me to do or accomplish? (Purpose)

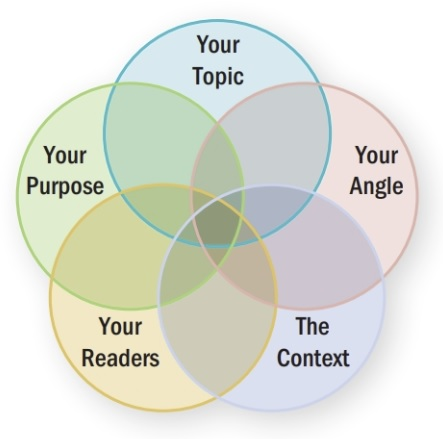

Whether you are writing for your class or for the workplace, you can use these key questions to help you identify the basic elements of your document’s “rhetorical situation” (Figure 9.1). The rhetorical situation has five elements: topic, angle, purpose, readers, and context. Writing and reading happen in social and rhetorical contexts. Gaining a clear understanding of your topic, angle, and purpose will help you figure out what you are writing about and what you want to prove. It will also help you decide which genre is most appropriate for your writing project. In college and in your career, you will need to write to real people who are reading your work at specific times and in specific places. Your writing needs to inform them, persuade them, and achieve your purpose. Your writing must speak to their specific needs, values, and attitudes.

Together, this information makes up the rhetorical situation—that is, the topic, angle, purpose, readers, and context. Each rhetorical situation is unique, because every new situation puts into play a writer with a purpose, writing for specific readers who are encountering the work at a unique time and place. When you have sized up the rhetorical situation, you can figure out what genre will best help you accomplish what you want to achieve.

What is the Rhetorical Situation?

Rhetoric is the purposeful use of language in speech or in writing. In other words, it’s the ways in which you, the speaker or the writer, purposely use language in different situations. Different situations require different language.

The rhetorical situation is any situation in which you are trying to communicate a message. A message is the main idea or point you are trying to convey. The medium (plural form: media) is the method of communication you use to disseminate that message.

Every time you:

- have a conversation

- send a text or e-mail

- post to social media

- write an essay

- watch a movie or TV show

- listen to music

You are part of a rhetorical situation!

There are five elements to consider in EVERY rhetorical situation.

An understanding of each of these elements and its relationship to all the other elements will help you throughout the writing process.

1. Topic: What Am I Writing About?

Topics are issues. You start with a broad issue, then choose an angle in the next step to approach it. For example, issues like elections, war, racial equality, and poverty are all topics.

Topics themselves aren’t new. Most have been around for as long as the human race, or at least since the dawn of civilization. It’s the specifics you choose to write about or the new information that makes a message unique.

In college, your professors will either provide the topics for your papers or ask you to come up with your own. When your professor supplies the topic, he or she will usually define the topic broadly, saying something like this: “For this paper, I want you to write about the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s.”

If your professor does not supply a topic, you should pick a topic that intrigues you and one about which you have something interesting to say. If you have no idea what you want to write about, make a list of ten topics that you like to read or talk about. In that list, you should be able find something you would enjoy spending some time writing about. When coming up with your own topic, you should consider the requirements of the writing assignment, the required length of the paper, and the complexity of the issue.

In your career, you will write about topics that are different than the ones you wrote about in college. Nevertheless, you should still begin by clearly identifying your topic. For instance, your supervisor or a client may request a document from you in the following way:

Examples

“Our organization is interested in receiving a proposal that shows how we can lower our energy costs with wind and solar power.”

“We want you to explore and report on the causes behind the sudden rise in violence in the Franklin South neighborhood.”

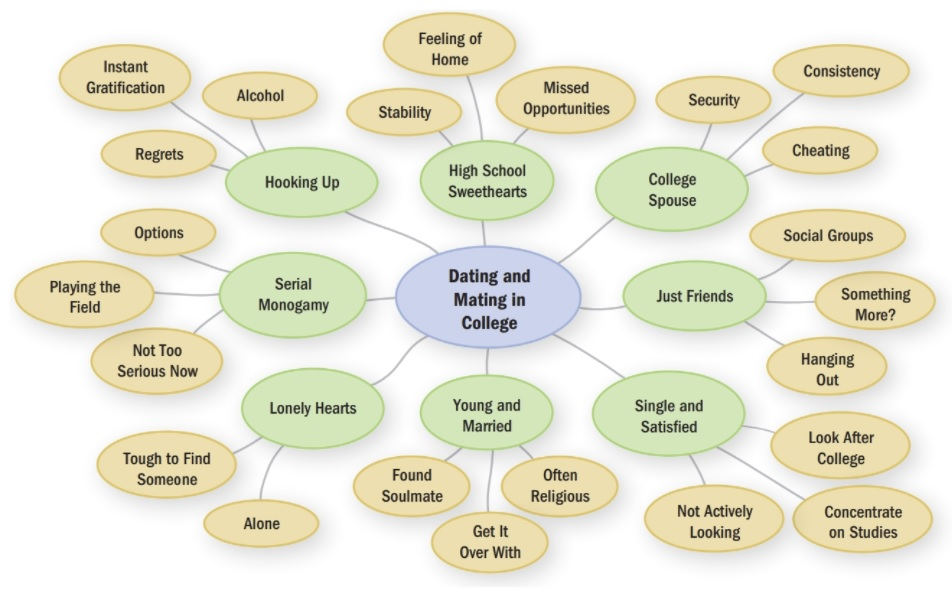

Once you have clearly identified your topic, you should explore its boundaries or scope, trying to figure out what is “inside” and what is “outside” the topic. A good way to determine the boundaries of your topic is to create a concept map like the one shown in Figure 9.2. To make a concept map, start out by writing your topic in the middle of a sheet of paper or your computer screen. Circle it, and then write down everything connected with it that comes to mind. Mapping on paper works well, but if you prefer mapping on a screen you can use free or low-cost apps like Coggle, XMind, Freemind, or Inspiration.

While mapping, write down all the things you already know about your topic. Then, as you begin to run out of ideas, go online and enter some of the words from your map into a search engine like Google, Yahoo!, or Bing. The search engine will bring up links to numerous other sources of information about your topic. Read through these sources and add more ideas to your concept map. As your map fills out, you might ask yourself whether the topic is too large for the amount of time you have available. If so, pick the most interesting ideas from your map and create a second concept map around them alone. This second map should help you narrow your topic to something you can handle.

2. Angle: What Is New About the Topic?

Like an angle in mathematics, angles in the rhetorical situation indicate the direction you choose to go or the way in which you choose to approach the topic.

You don’t need to discover a new topic for your writing assignment. Instead, you need to come up with a new angle on an existing topic. In choosing an angle, you want to make sure that your message is new or different. Your angle is your unique perspective or view on the issue. Think about facets of your topic that aren’t well-known or look at what’s new concerning your topic. A good way to identify a new angle is to ask yourself, “What has changed about this topic that makes it interesting right now?” Another question you can ask is, “What unique experiences, expertise, or knowledge do I have about this topic?”

Let’s consider these two questions separately.

What Has Changed That Makes This Topic Interesting Right Now?

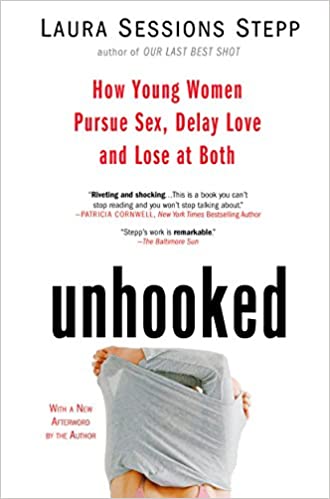

Imagine you are searching for information about college dating trends. At your library, you find a 2011 book by Laura Sessions Stepp titled Unhooked: How Young Women Pursue Sex, Delay Love, and Lose at Both (Figure 9.3). The book seems a little out of date, but you mostly agree with the author’s main points, especially her arguments about women avoiding long-term relationships while in college so they can focus on their studies and careers. However, you also believe social networking like Twitter, Pinterest, Instagram, and Tumblr have somewhat cooled off the hooking up culture that once existed. Now, college students can use social networking to get that feeling of intimacy with others rather than seeking intimacy by pairing off for the night. That could be your angle on this topic.

What Unique Experiences, Expertise, or Knowledge Do I Have About This Topic?

Your experiences as a college student give you some additional insights or “angles” into the real college dating scene. For example, perhaps your own experiences tell you that the hooking-up culture has been replaced by a culture of “serial monogamy” in which college students now go through a series of short-term emotional and physical relationships while they are in college. These so-called monogamous relationships may last a few months or perhaps a year, but most people don’t expect them to lead to marriage. That’s another possible angle on this topic.

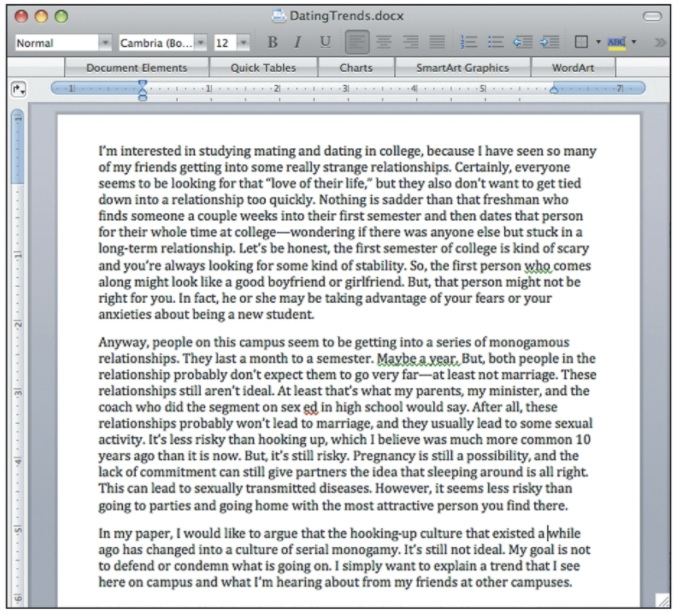

To see if one of these angles works, do some freewriting to get your ideas on the screen (Figure 9.4). Freewriting involves opening a new page in your word processor and writing anything that comes to mind. Freewrite for about five minutes, and don’t stop to correct or revise. If you run out of material, type and finish the phrases, “What I really mean to say is . . .” or “I remember . . .” These kinds of prompts will help you get rolling again.

Dating and mating in college is a very large topic—too large for a five-to ten-page paper. But if you explore a specific angle (e.g., the shift from a hooking-up culture to a culture of serial monogamous relationships), you can say something new and interesting about how people date and mate in college.

3. Audience: Who am I writing for, and what do they expect?

The audience is who receives your message. There are two types of audience:

- The intended audience is whomever you want to receive your message. They are your target audience.

- Your real audience is whomever actually receives your message.

In college courses, the real audience will always be your instructor, but for the sake of an assignment you may be instructed to select or write to an intended audience.

We use demographics, the grouping of people for statistical purposes, to explain audience. There’s no limit to how we can divide people into groups: by age, gender, race, income, geography, even hair color, shoe size, or favorite food.

Before you start writing, develop a reader profile that helps you adapt your ideas to your readers’ needs and the situations in which they will use your document. A profile is an overview of your readers’ traits and characteristics. At a minimum, you should develop a brief reader profile that gives you a working understanding of the people who will be reading your text. If time allows, create an extended reader profile that will give you a more in-depth view of their needs, values, and attitudes.

A Brief Reader Profile

To create a brief reader profile, you can use the Five-W and How questions (Heuristics) to describe the kinds of people who will be reading your text.

- Who are my readers? What are their personal characteristics? How young or old are they? What cultures do they come from? Are they familiar with your topic already or are they completely new to it?

- What are their expectations? What information do they need from you to make a decision? What ideas excite them, and what bores them? What information do they need to accomplish their personal and professional goals?

- Where will they be reading? Will your readers be sitting at their desks, in a meeting, or on an airplane? Will they be reading from a printed page, a computer screen, a tablet computer, or a small-screen device like a smartphone?

- When will they be reading? Will they be reading when the issue is hot and under discussion? Does the time of day affect how they will read your document?

- Why will they be reading? Why will they pick up your document? Do they want to be informed, or do they need to be persuaded?

- How will they be reading? Will they read slowly and carefully? Will they skip and skim? Will they read some parts carefully and other parts quickly or not at all?

Your answers to the Five-W and How questions will give you a brief reader pro-file to help you start writing.

An Extended Reader Profile

When you are writing complex or high-stakes documents, like proposals or formal reports, you should create an extended reader profile that goes beyond answering the Who, What, Where, When, Why, and How questions. An extended reader profile will help you to better anticipate your readers’ needs, values, and attitudes toward you and your topic.

What are their needs?

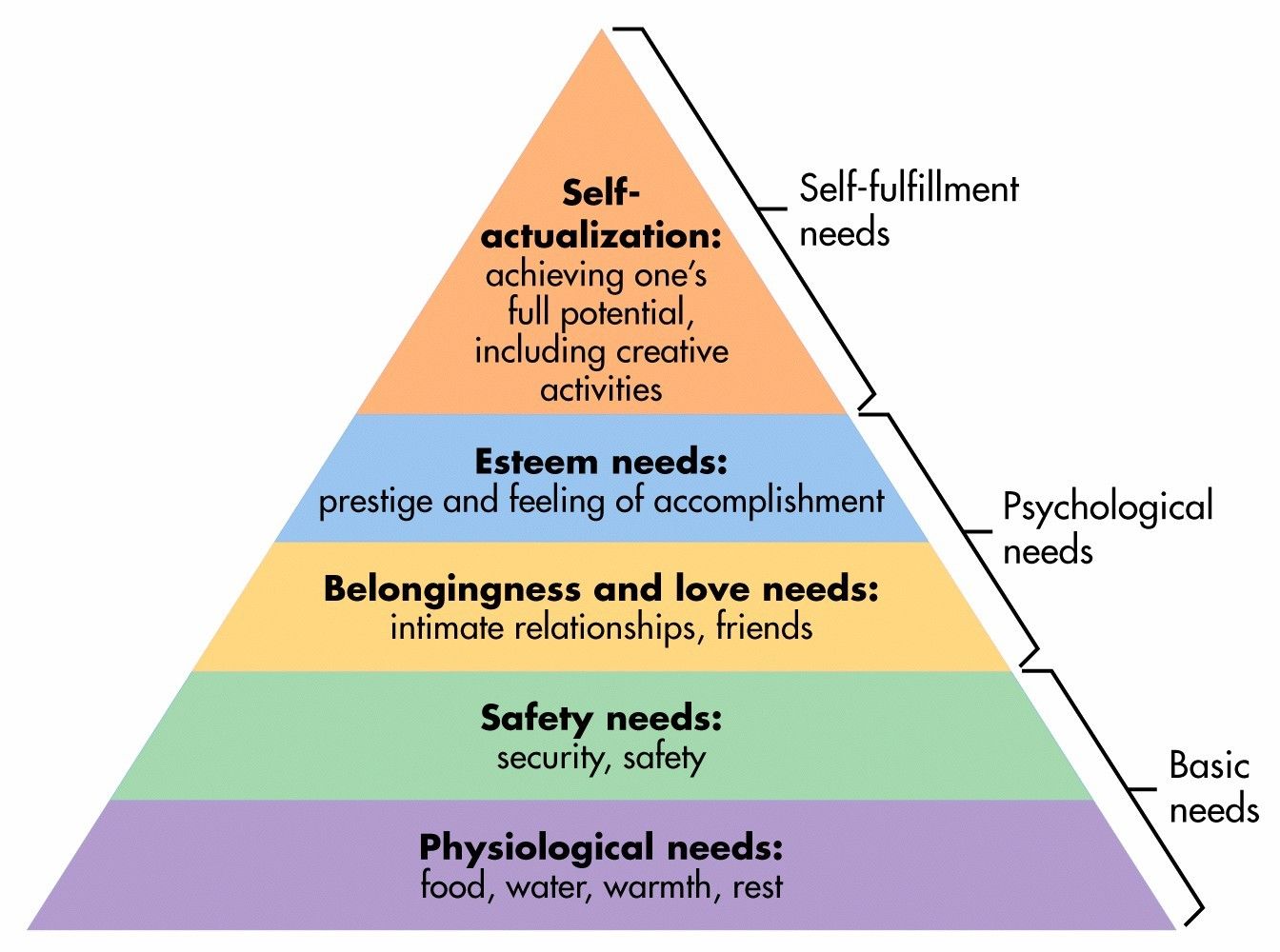

Your readers probably picked up your document because they need something. Do they need specific information about your topic? What do they need in order to do something or achieve a goal? What are their life goals, and what do they need to achieve them? Make a list of the two to five needs that your readers expect you to fulfill in your document for it to be useful to them. It helps to think broadly about what people in general need and why. American psychologist Abraham Maslow developed a helpful tool for identifying people’s needs. He suggested that human needs could be organized into five levels that move from lower-level physiological needs (food, air, sleep) to higher-level self-actualization needs (creativity, spontaneity, morality). Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, as it is called, is often illustrated as a pyramid like the one in Figure 9.5.

One thing to keep in mind is that Maslow’s ranking of needs is culturally dependent, so people from different cultures may value some needs more than others.

What are their values?

Values involve personal beliefs, social conventions, and cultural expectations. Your readers’ values have been formed through their personal experiences, family or religious upbringing, and social/cultural influences.

- Personal values. Like you, your readers have beliefs, principles, and standards of behavior that are important to them. Think about your readers’ upbringings and experiences. What are their core beliefs? What makes your readers and their values unique or different?

- Customs of their society. Think about how your readers behave with others in their own social circles. What expectations do their friends and family place on them? What traditions or codes govern their behavior?

- Cultural values. Your readers’ culture may influence their behavior in ways even they don’t fully understand. What do people in their culture value? How are these cultural values similar to or different from your cultural values?

Mistakenly, writers sometimes assume that their readers hold the same values as they do. Even people who seem similar to you in background and upbringing may have very different ways of seeing the world.

What is their attitude toward you and the issue?

Your readers will also have a particular attitude about your topic and, perhaps, about you. Will they be excited about your topic or will they find it boring? Are they concerned, apathetic, happy, or upset about your topic? Do you think they already accept your ideas, or are they deeply skeptical? What are their positive or negative feelings about you and the issue?

If your readers are positive and welcoming toward your views, you will want to encourage their goodwill by giving them compelling reasons to agree with you. If they are negative or resistant, you will want to use solid reasoning, sufficient examples, and good style to counter their resistance and help them understand your point of view.

Using a Reader Analysis Worksheet

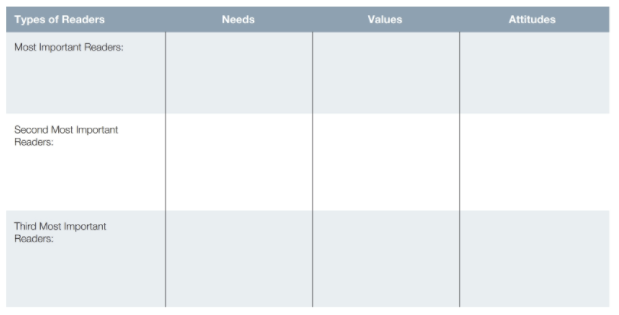

Anticipating all of your readers’ needs, values, and attitudes can be especially difficult if you try to do it all in your head. That’s why professional writers often use a reader analysis worksheet to help them create an extended profile of their readers.

Using the reader analysis worksheet is easy. On the left, list the types of people who are likely to read your document, ranking them by importance. Then, fill in what you know about their needs, values, and attitudes. If you don’t know enough to fill a square, just put a question mark (?) in that area. Question marks signal places where you need to do some additional research on your readers.

An extended reader profile (Figure 9.6) blends your answers to the Five-W and How questions with the information you added to the Reader Analysis Worksheet. These two reader analysis tools should give you a strong understanding of your readers and how they will interpret your document.

4. Context: How Will My Audience be Reading What I’ve Written?

The context of your document involves the external influences that will shape how your readers interpret and react to your writing. Keep in mind that readers react to a text moment by moment, so the happenings around them can influence their understanding of your document. Your readers will be influenced by three kinds of contexts: place, medium, and social and political issues.

Place

Earlier, when you developed a brief profile of your readers, you answered the Where and When questions to figure out the locations and times in which your readers would use your document. Now go a little deeper to put yourself in your readers’ place.

- What are the physical features of this place?

- What is visible around the readers, and what can they hear?

- What is moving or changing in this place?

- Who else is in this place, and what do they want from my readers?

- What is the history and culture of this place, and how does it shape how people view things?

A place is never static. Places are always changing. So figure out how this place is changing and evolving in ways that influence your readers and their interpretation of your text. The genre of your document may help you to imagine the places where people are likely to read it. Memoirs, profiles, reviews, and commentaries tend to be read in less formal settings—at home, on the bus, or in a café. Proposals and reports tend to be read in office settings, and they are often discussed in meetings. Once you know the genre of your document, you can make decisions about how it should be designed and what would make it more readable in a specific place.

Medium

The medium is the technology that your readers will use to interact with your document. Each medium (e.g., paper, Web site, public presentation, video, podcast) has its strengths and weaknesses. Each interprets your words and react to your ideas.

- Paper documents. Paper documents are often read more closely than on-screen documents. With paper, your readers may be patient with longer paragraphs and extended reasoning. Document design can make a paper document more attractive and help people read more efficiently. In print documents, readers appreciate graphics and photographs that enhance and reinforce the words on the page.

- Electronic documents. When people read text on a screen, they usually “raid” it, reading selectively for the information they need. They tend to be impatient with long documents, and they generally avoid reading lengthy paragraphs. They appreciate informative and interesting visuals like graphs, charts, and photographs that will enhance their understanding

- Public presentations. Presentations tend to be much more visual than on-screen and print documents. A presentation made with PowerPoint or Keynote usually boils an original text down to bullet points that highlight major issues and important facts.

- Podcasts or videos. A podcast or video needs to be concise and focused. Hearing or seeing a text can be very powerful in this multimedia age; however, amateur-made podcasts and videos are easy to spot. The people listening to your podcast or watching your video will expect a polished, tight presentation.

Social and Political Influences

Now, think about the current trends and events that will influence how your readers interpret what you are telling them.

- Social trends. Pay attention to the social trends that are influencing you, your topic, and your readers. You originally decided to write about this topic because you believe it is important right now. What are the larger social trends that will influence how people in the near and distant future understand this topic? What is changing in your society that makes this issue so significant? Most importantly, how do these trends directly or indirectly affect your readers?

- Economic trends. For many issues, it all comes down to money. What economic fac-tors will influence your readers? How does their economic status shape how they will interpret your arguments? What larger economic trends are influencing you and your readers?

- Political trends. Also, keep any political trends in mind as you analyze the context for your document. On a micropolitical level, how will your ideas affect your readers’ relationships with you, their families, their colleagues, or their supervisors? On a macropolitical level, how will political trends at the local, state, federal, and international levels shape how your readers interpret your ideas?

Naturally, readers respond to the immediate context in which they live. If you understand how place, medium, and social and political trends influence your readers, you can adapt your work to their specific needs, values, and attitudes.

5. Purpose: What Do I Want to Accomplish?

Your purpose is what you want to accomplish. Everything you write has a purpose, even informal kinds of writing like texting. Whenever you speak or write, you are trying to inform, ask a question, flirt, persuade, impress, or just have fun. When writing for college or for the workplace, figure out what you want to achieve (your purpose) before you get too far into the writing process. Your professor may have already identified a purpose for your paper in the assignment, so check there first. Assignments based on topics might look like this: “Your objective in this paper is to show how Martin Luther King, Jr.’s use of nonviolent tactics changed the dynamics of racial conflict in the 1960s, undermining the presumption of white dominance among blacks and whites” or “Use close observation of students on our campus to support or debunk some of the common assumptions about dating and mating in college.”

If you need to come up with your own purpose for the paper, ask yourself what you believe and what you would like to prove about your topic. For example, at the end of the freewrite in Figure 17.4, a purpose statement is starting to form:

Example

This statement is still a bit rough and it lacks a clear focus, but the purpose of the project is starting to take shape.

Are You Informing or Persuading?

At this point, your purpose statement can help you figure out two important things about your paper. First, it will help you determine whether you are trying to inform your readers about something or whether you are trying to persuade them. Second, your purpose statement will help you come up with your paper’s working thesis. You might find it helpful to remember that in almost everything you write in college and in the workplace, your primary purpose involves informing or persuading. So your purpose statement will usually be built around these kinds of verbs:

- Informative Papers: inform, describe, define, review, notify, advise, explain, demonstrate

- Persuasive Papers: persuade, convince, argue, recommend, advocate, urge, defend, justify, support

Once you determine whether you are informing or persuading your readers, you will find it much easier to come up with a thesis statement that will focus your paper.

Thesis Statement (Main Claim)

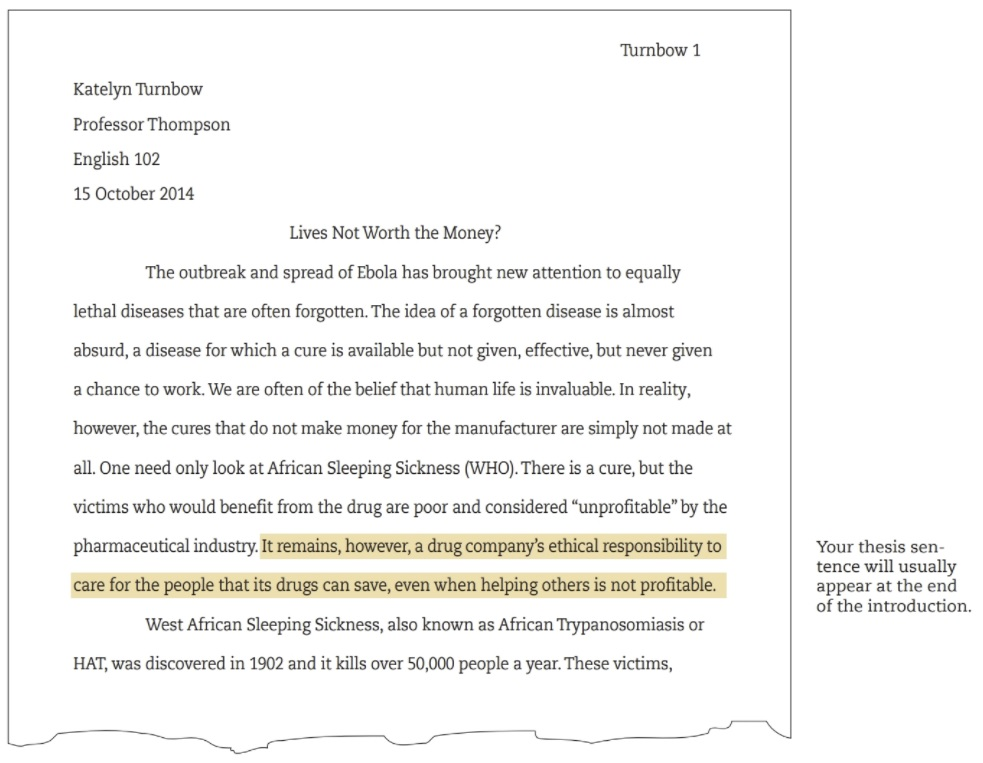

Your paper’s thesis statement (also known as your “main point” or “main claim”) should be similar to your purpose statement. A purpose statement guides you, as the writer, by helping you develop your ideas and draft your paper. Your thesis statement guides your readers by announcing the main point or claim of the paper.

The thesis statement in your paper will usually first appear in your introduction (Figure 9.7).

Then it reappears, typically with more emphasis, in the conclusion. In special cases, you may choose to use a “question thesis” or “implied thesis” in which a question or open-ended comment in the introduction sets up a thesis statement that appears only in the conclusion of the document.

See Chapter 5: Thesis Statements for more advice on writing your main idea or claim.

Choosing the Appropriate Genre

Besides helping you come up with your thesis statement, your purpose statement will also help you figure out which genre is appropriate for your paper. In some cases, your professor has already identified the genre by asking you to write a “review,” a “literary analysis,” a “proposal,” or a “research paper.” If so, you can turn to that chapter (19-21) in this book to learn about the expectations for that genre (Section III: Rhetoric).

If your professor doesn’t specify a genre, the best way to figure out which one would work best is to look closely at your purpose statement. Your thesis sentence will signal which genre would be best for your paper. Look for verbs like “argue,” “propose,” “analyze,” “explain,” or “research.” These verbs will often tip you off to the genre you need (argument paper, proposal, analytical report, explainer, or research paper).

The genre that fits your purpose statement will help you make strategic decisions about how you are going to invent the content of your paper, organize it, develop an appropriate style, and design it for your readers.

The broad idea or issue that a message deals with.

The unique viewpoint, new information, or interesting take on a topic.

The circumstances that form the setting for an event, statement, or idea, and in terms of which it can be fully understood and assessed.

The goal or objective that the creator of a message is trying to achieve by communicating that message.

Any set of circumstances that involves at least one person (the author) communicating a message to at least one other person (the audience).

The main idea or point that an author is trying to convey.

A diagram that depicts suggested relationships between concepts.

A prewriting technique in which a person writes continuously for a set period of time without worrying about rhetorical concerns or conventions and mechanics.

The group of people that an author is trying to reach with their message.

The group of people who actually receive a message.

A method of grouping people into categories for the purpose of collecting data.

A discovery tool that helps you ask insightful questions or follow a specific pattern of thinking.

(1908-1970) An American psychologist best known for creating Maslow's hierarchy of needs, a theory of psychological health predicated on fulfilling innate human needs in priority, culminating in self-actualization.

A motivational theory in psychology comprising a five-tier model of human needs, often depicted as hierarchical levels within a pyramid. Needs lower down in the hierarchy must be satisfied before individuals can attend to needs higher up.

The method of communication that an author uses to disseminate their message. Plural: media.

The main idea, point, or claim of a written work. Plural: theses.

A category of artistic composition, as in music or literature, characterized by similarities in form, style, or subject matter.