12

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Use reliable strategies to find electronic sources. (GEO 1; SLO 2)

- Collect evidence from a variety of print sources. (GEO 1; SLO 2)

- Do your own empirical research with interviews, surveys, and field observations. (GEO 1, 2; SLO 2)

A research plan should begin after you can clearly identify the focus of your argument. First, inform yourself about the basics of your topic (Wikipedia and general online searches are great starting points). Be sure you’ve read all the assigned texts and carefully read the prompt as you gather preliminary information. This stage is sometimes called pre-research.

A broad online search will yield thousands of sources, which no one could be expected to read through. To make it easier on yourself, the next step is to narrow your focus. Think about what kind of position or stance you can take on the topic. What about it strikes you as most interesting? Refer back to the prewriting stage of the writing process, which will come in handy here.

Finding Electronic and Online Sources

The Internet is a good place to start researching your topic. Keep in mind, though, that the Internet is not the only place to do research. You should use print and empirical sources to triangulate the evidence you find on the Internet.

Using Internet Search Engines

Search engines let you use keywords to locate information about your topic. If you type your topic into Google, Bing, or Yahoo!, the search engine will return many thousands of sites. With a few easy tricks, though, you can target your search with some common symbols and strategies.

For example, let’s say you are researching how sleep deprivation affects college students. You might start by entering the phrase:

sleep deprivation

You will get many more results than you need, and they may not all apply to college students. To narrow down your search results, add another keyword using the word “and.”

sleep deprivation and college students

With this generic subject, a search engine will pull up millions of Web pages that might refer to this topic. Of course, there is no way you are going to have time to look through all those sites to find useful evidence, even if the search engine ranks them for you.

So you need to target your search to pull up only the kinds of materials you want. Here are some tips for getting better results:

- Use exact words. Choose words that exactly target your topic, and use as many as you need to sharpen your results. For example:

- sleep deprivation effects on students test taking

- Use quotation (“ ”) marks. If you want to find a specific phrase, use quotation marks to target those phrases.

- “sleep deprivation” effects on students and “test taking”

- Use brackets ([ ]). If you want to search for phrases in any order (contrary to using quotation marks, brackets will do that for you.

- “sleep deprivation” [causes and effects]

- Use the plus (+) sign. If you put a plus (+) sign in front of a word, the search engine will only find pages that have that exact word in them.

- sleep +deprivation effects on +students +test +taking

- Use the minus (-) sign. If you want to eliminate any pages that refer to words or phrases you don’t want to see, you can use the minus sign to eliminate pages that refer to them.

- sleep deprivation +effects on students +test +taking -insomnia -apnea

- Use wildcard symbols. Some search engines have symbols for “wildcards,” such as ?, *, or %. These symbols are helpful when you know most of a phrase, but not all of it. For example, by using the prefix “neuro” followed by the wildcard symbol, a search engine will list results with the words neurology, neuroscience, neurobiology, neuropsychology, neurons, neurologist, etc. This can compile results from a spectrum of search terms at once.

- “sleep deprivation” +neuro*

- Use “or.” This will search for either topic at once. For example, the below search terms will search for results with “sleep deprivation” +students AND “sleep deprivation” +college at the same time.

- “sleep deprivation” +students or college

- Use a tilde (~). A tilde will search for a word as well as its synonyms. This avoids having to do multiple searches for similar terms. For example, the search below will not only find results with the word college, but associated words such as university and higher education.

- “sleep deprivation” and ~college

- Find related results. It’s easy to search for your terms in addition to ones related to what you are looking for. Let’s say you want to search for conditions related to sleep deprivation. By using the word “related,” the search engine will also show you results containing topics like insomnia or sleep medications.

- “college students” and related: “sleep deprivation”

- Search specific sites. If you know a web site that you would like a search, you can search within that site using a search engine. For example, let’s say that early in your research process you remember seeing a great article on sleep deprivation in college students from The Atlantic. However, you don’t remember the title of the article, who wrote it, or when it was written. No problem! You can easily find what you are looking with the following search terms:

- “sleep deprivation” site: theatlantic.com

- Search for specific files. If you are looking for presentations on your topic, for instance, you may wish to search for files ending in “.pptx” (PowerPoint). You can search for any file type, such as a PDF or image file such as JPEG. Simply use the word “file” and the file type (what comes after a file name).

- “sleep deprivation” file:.pptx

- Search for specific dates. If you are looking for information that was published during a certain time, you can do so by entering the date range with two periods between them. This is especially useful if you are only looking for current results or if you want information from a certain point in history.

- “sleep deprivation” 2010..2020

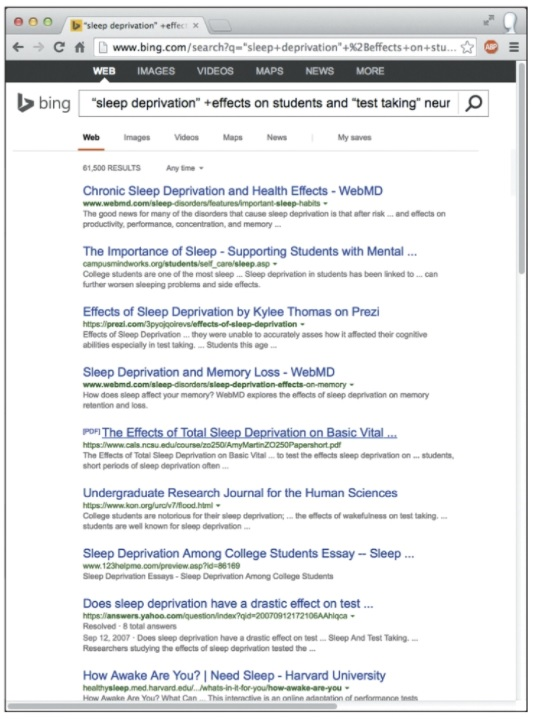

These search engine tips will help you pull up the pages you need. Figure 12.1 shows the results of a Bing search using the phrase:

“sleep deprivation” effects on students “test taking” −insomnia –apnea

Note that the first items pulled up by some search engines may be sponsored links. In other words, these companies paid to have their links show up at the top of your list. Most search engines highlight these links in a special way. You might find these links useful, but keep in mind that the sponsors are biased because they probably want to sell you something.

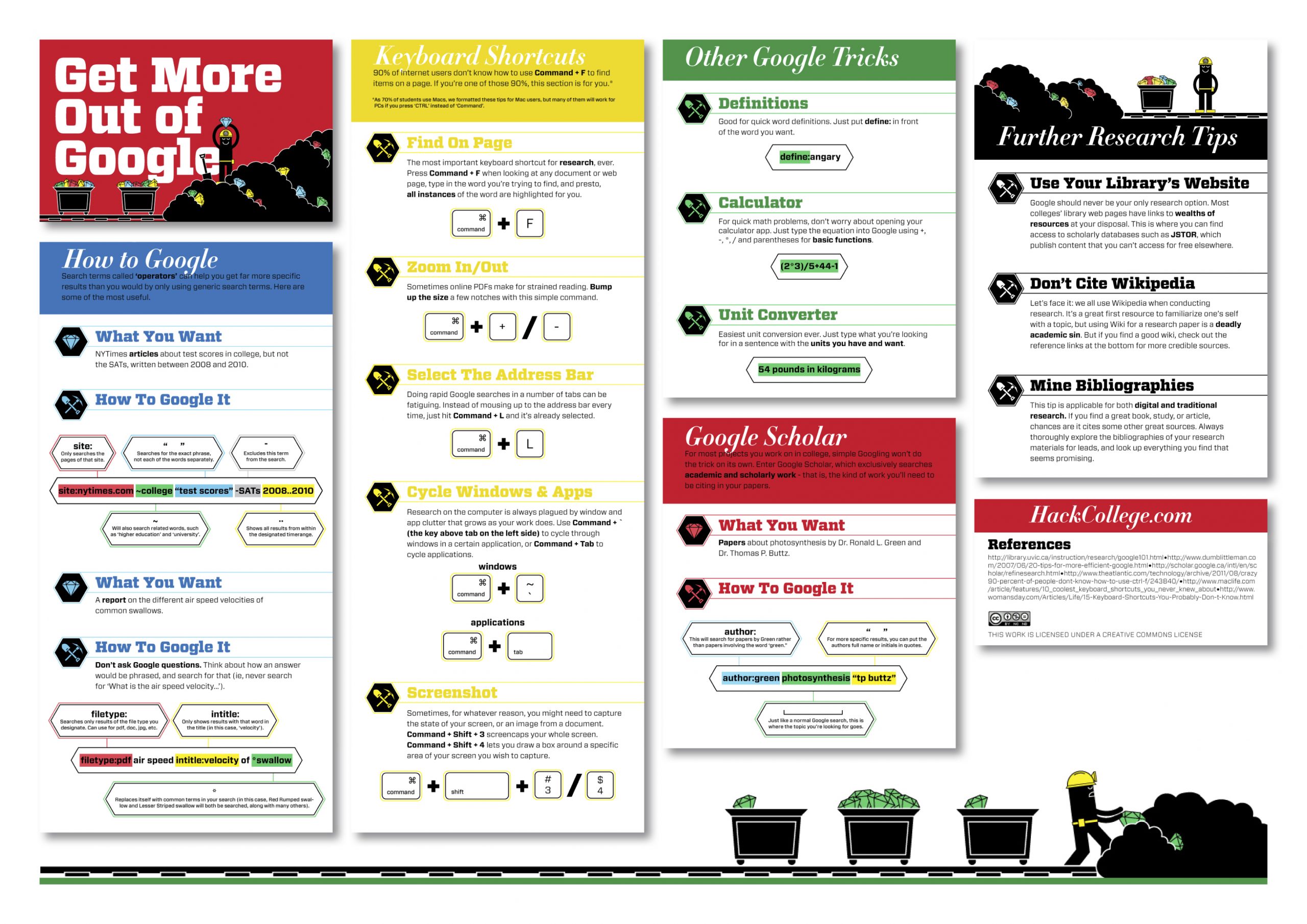

Lastly, while some search engines allow for you to search using whole sentences or questions (such as Google), others (such as databases) only allow for keyword searches. That means if you search Google for “What is the leading cause of sleep deprivation in college students?” you will probably find some worthy results. However, if you typed the same question into a database, you would not find any results because the search contains too many keywords. Therefore, it is important to know how to search using keywords and the symbols to better search any engine. The infographic below outlines some of Google’s helpful search features.

Google Scholar

An increasingly popular article database is Google Scholar. It looks like a regular Google search, and it aims to include the vast majority of scholarly sources available. While it has some limitations (like not including a list of which journals they include), it’s a very useful tool if you want to cast a wide net.

Here are three tips for using Google Scholar effectively:

- Add your topic field (economics, psychology, French, etc.) as one of your keywords. If you just put in “crime,” for example, Google Scholar will return all sorts of stuff from sociology, psychology, geography, and history. If your paper is on crime in French literature, your best sources may be buried under thousands of papers from other disciplines. A set of search terms like “crime French literature modern” will get you to relevant sources much faster.

- Don’t ever pay for an article. When you click on links to articles in Google Scholar, you may end up on a publisher’s site that tells you that you can download the article for $20 or $30. Don’t do it! You probably have access to virtually all the published academic literature through your library resources. Write down the key information (authors’ names, title, journal title, volume, issue number, year, page numbers) and go find the article through your library website. If you don’t have immediate full-text access, you may be able to get it through an inter-library loan.

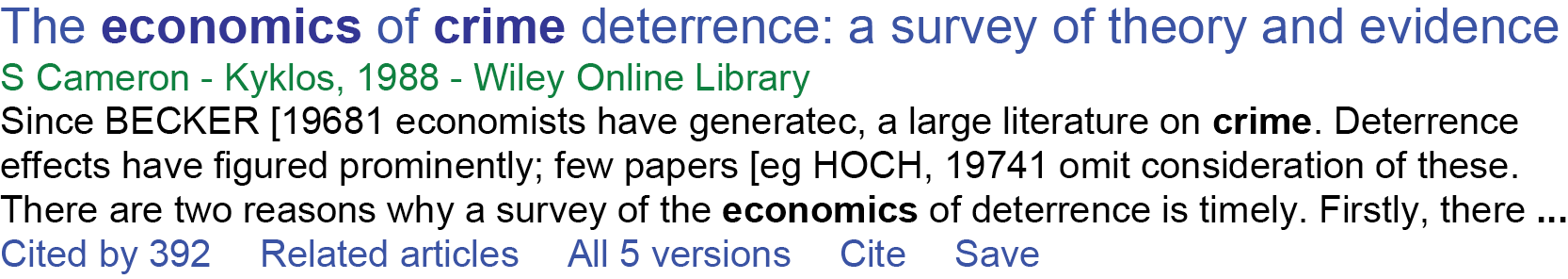

- Use the “cited by” feature. If you get one great hit on Google Scholar, you can quickly see a list of other papers that cited it. For example, the search terms “crime economics” yielded this hit for a 1988 paper that appeared in a journal called Kyklos:

Watch this video to get a better idea of how to utilize Google Scholar for finding articles. While this video shows specifics for setting up an account with Eastern Michigan University, the same principles apply to other colleges and universities. Ask your librarian if you have more questions.

Using the Internet Cautiously

Many of the so-called “facts” on the Internet are really just opinions and hearsay. Some stories are actually “fake news,” created to mislead people about important issues and current events. Also, many quotes that appear on the Internet have been taken out of context or corrupted in some way. So use information from the Internet critically and even skeptically. Don’t get fooled by a professional-looking Web site, because a good Web designer can make just about anything look professional. In the previous chapter (Chapter 11: Sources), you learned some questions for checking the reliability of any source.

The Internet will help you find plenty of useful, reliable evidence, but there is also a great amount of junk. It’s your responsibility as a researcher to critically evaluate what is reliable and what isn’t.

Using Documentaries and Television/Radio Broadcasts

Multimedia resources such as television and radio broadcasts are available online through network Web sites as well as sites like YouTube and Hulu. Depending on who made them, documentaries and broadcasts can be reliable sources. If the material is from a trustworthy source, you can take quotes and cite these kinds of electronic sources in your own work.

- Documentaries. A documentary is a nonfiction movie or program that relies on interviews and factual evidence about an event or issue. A documentary can be biased, though, so check into the background of the person or organization that made it.

- Television broadcasts. Cable channels and news networks like CNN, HBO, BBC, PBS, the History Channel, the National Geographic Channel, and the Biography Channel are producing excellent broadcasts that are reliable and can be cited as support for your argument. However, programs on news channels that feature just one or two highly opinionated commentators are less reliable because they tend to be sensationalistic and biased.

- Radio broadcasts. Radio broadcasts, too, can be informative and authoritative. Public radio broadcasts, such as those from National Public Radio and American RadioWorks, offer well-researched stories on the air and at their Web sites. On the other hand, political broadcasts like The Sean Hannity Show, The Rush Limbaugh Show, The Rachel Maddow Show, and The Thom Hartmann Show are often criticized for slanting the news and playing loose with the facts. You probably cannot rely on these broad-casts as factual sources in your argument.

Using Wikis, Blogs, and Podcasts

In the past, wikis, blogs, or podcasts were often considered too opinionated or subjective to be usable as sources for academic work. However, they are becoming increasingly reliable because reputable scholars and organizations are beginning to use these kinds of new media to publish research-based information. These electronic sources are especially helpful for defining issues and helping you locate other sources.

- Wikis. You already know about Wikipedia, the most popular wiki, but a variety of other wikis are available, like WikiHow, Wikibooks, and Wikitravel. Wikis allow their users to add and revise content, and they rely on other users to back-check facts. On some topics, such as popular culture (e.g., television programs, music, celebrities), a wiki might even be the best or only source of up-to-date information. On more established topics, however, you should always be skeptical about the reliability of the information because these sites are written anonymously and can be changed frequently. Your best approach is to use these sites primarily for start-up research on your topic and to find leads that will help you locate other, more reliable sources.

- Blogs. Blogs can be helpful for exploring a range of opinions on a particular topic. However, even some of the most established and respected blogs like Daily Kos, Power Line, and Wonkette are little more than opinionated commentaries on the day’s events. Blogs can help you identify the topic’s issues and locate more reliable sources; however, most blogs cannot be considered reliable sources themselves. If you want to use a blog as a source, you should explain in your paper why the author of the blog is a trusted source who is supporting the argument with reliable evidence.

- Podcasts. Most news Web sites offer podcasts and vidcasts, but the reliability of these sources depends on who made the audio or video file. Today, anyone with a mobile phone, digital recorder, or video camera can make a podcast, even a professional-looking podcast, so you need to carefully assess the credibility and experience of the person who made it.

On just about every topic, you will find plenty of people on the Internet who have opinions. The problem with online sources is that just about anyone can create or edit them. That’s why the Internet is a good place to start collecting evidence, but you need to also collect evidence from print and empirical sources to triangulate what you find online.

Finding Print Sources

With such easy access to electronic and online sources, people sometimes forget to look for print sources on their topic. That’s a big mistake. Print sources are typically the most reliable forms of evidence on just about any subject.

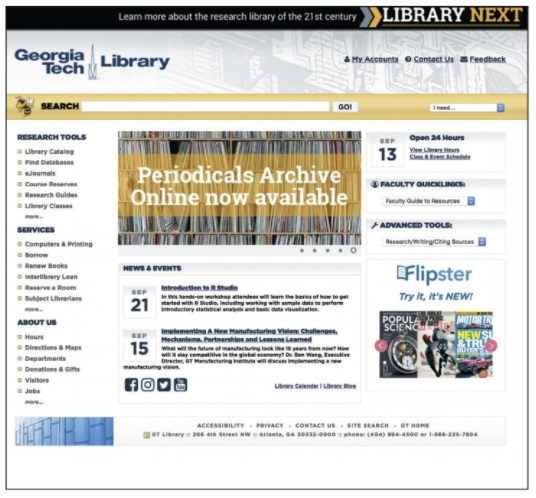

Locating Resources at Your Library

You can easily find useful books at your campus or local public library. More than likely, your university’s library Web site has an online search engine that you can access from any networked computer (Figure 12.2). This search engine will allow you to locate books in the library’s catalog. Also, your campus library will likely have research librarians who can help you find useful print sources. Ask for a research librarian at the library’s Information Desk.

- Books. The most reliable information on your topic can usually be found in books. Authors and editors of books work closely together to check their facts and gather the best evidence available. So books are usually more reliable than Web sites. The downside of books is that they tend to become outdated in fast-changing fields.

- Government publications. The US government produces an amazing amount of printed material on almost any topic you could imagine. Government Web sites, like The Catalog of U.S. Government Publications, are good places to find these sources. Your library probably collects many of these materials because they are usually free or inexpensive.

- Reference materials. The reference section of your library collects helpful reference tools, such as almanacs, directories, encyclopedias, handbooks, and guides. These reference materials can help you find facts, data, and evidence about people, places, and events.

Right now, entire libraries of books are being scanned and posted online. Out-of-copyright books are appearing in full-text versions as they become available. Online versions of copyrighted books are searchable, allowing you to see excerpts and identify pages on which you can locate the specific evidence you need.

Using the Library’s Databases

As we learned earlier, the strongest articles to support your academic writing projects will come from scholarly sources. Finding exactly what you need becomes specialized at this point, and requires a new set of searching strategies beyond even Google Scholar. For this kind of research, you’ll want to utilize library databases, as this video explains.

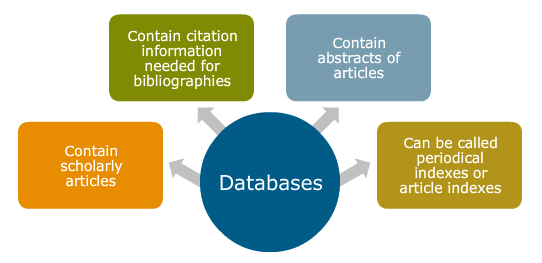

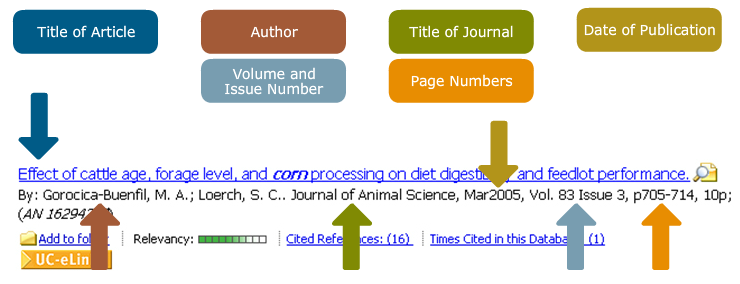

At your library, you can find articles in academic journals, magazines, and newspapers. These articles can be located using online databases or periodical indexes available through your library’s Web site. A database is a collection of searchable information. Databases can contain any type of source from photographs to sheet music to algebraic theorems, but most of your research using databases utilize the following sources:

- Academic journals. Articles in journals are usually written by scientists, professors, consultants, and subject matter experts (SMEs). These journals will offer some of the most exact information available on your topic. To find journal articles, start by searching in a periodical index related to your topic. Some of the more popular periodical indexes include:

- Magazines. You can find magazine articles about your topic in the databases. Print versions may be available in your library’s periodical or reference rooms.

- Newspapers. For research on current issues or local topics, newspapers often provide the most recent information. At your library or through its Web site, you can use newspaper indexes to search for information.

Finding Articles in Databases

The following video demonstrates how to search within a library database. The same general search tips apply to nearly all academic databases. Get familiar with your own school’s library homepage to identify the general search features, find databases, and practice searching for specific articles.

Tips for searching San Jac’s Library Databases:

1. Go to the library’s website at www.sanjac.edu/library and select the tab that reads “Article Databases.”

2. Databases are grouped by subject, so if you are doing research for a course, you can find databases relevant to your coursework by selecting the corresponding subject from the menu. For example, if you are conducting research for a psychology course, you would find relevant databases by clicking on the subject called “Social & Behavioral Sciences.”

3. If you are doing pre-research or have not decided what topic you want to write about yet, you should start with a general database. These are located under the subject “Multi-Subject/General Research [These cover virtually every subject].” The best general research database at San Jac is the Academic Search Complete. The following video from North Virginia Community College demonstrates how to search using this database.

4. If you already know your topic, it may be best to continue to a subject-specific database. These are the databases we will be using in this course for our remaining essays:

- General Research: Academic Search Complete (located under “Multi-Subject/General Research [These cover virtually every subject]”

- Current Events: Newspaper Source Plus (located under “Newspapers & Other Primary Source Materials”)

- Historical Context: History Reference Center (located under “History”)

- Literature: Literary Reference Center, Literature Resource Center, Bloom’s Literary eBook Collection, Twayne’s Authors Series (located under “Literature”)

- Persuasion: Issues & Controversies, Opposing Viewpoints (located under “Multi-Subject/General Research [These cover virtually every subject]”

5. Remember to select “full text” when searching to avoid searching through results that do not have the actual text.

6. Utilize the search terms and symbols explained in the “Using Search Engines” section of this chapter. Pay attention to the types of sources you are required to use for your assignment. If sources must be current, then select a date range. If your sources must be peer-reviewed, check that box when searching. If you must use sources from academic journals, select that source type in the advanced search options.

7. When you find an article you may want to use or get back to in the future, use the tools menu in the database to download, save, print, or email the article. These tools will also formulate a citation for you, but they often contain errors, so it’s best to check these citations before using them in your essay. You will learn how to cite sources, including databases, in Section V of this textbook. If you are saving or sending the article’s link, be sure to use the permalink and not the URL in your browser.

8. If you are not having any luck finding a useful source, try different keywords or a different database. Chances are, there are multitudes of information on your topic available, you just need to know how to find them. If you still can’t find what you are looking for, contact the librarians. They maintain the databases and are specially trained to use them.

In a previous chapter (Chapter 11: Sources), you learned some of the pros and cons of using different types of sources. Databases are ultimately the best of both the electronic and print worlds. They are convenient and easy to use, like web sources. Databases also contain information that would not appear in Google search results because it is behind a paywall. Many publications charge subscription or access fees to read their content, but the databases that San Jac has purchased will allow you to access this content at no cost. Additionally, because most databases contain print media (i.e. journal, newspaper, and magazine articles) they are overall more reputable and trustworthy than the search results you will find on the web. You can access information exclusively from academics or other professionals and know exactly where it came it from.

Using Empirical Sources

Empirical sources include observations, experiments, surveys, and interviews. They are especially helpful for confirming or challenging the claims made in your electronic, online, and print sources. For example, if one of your electronic or online sources claims that “each day, college students watch an average of five hours of television but spend less than one hour on their homework,” you could use observations, interviews, or surveys to confirm or debunk that statement.

Interviewing People

Interviews are a great way to go behind the facts to explore the experiences of experts and regular people. Plus, interviewing others is a good way to collect quotes that you can add to your text. Here are some strategies for interviewing people:

Prepare For The Interview

1. Do your research. You need to know as much as possible about your topic before you interview someone about it. If you do not understand the topic before going into the interview, you will waste your own and your interviewee’s time by asking simplistic or flawed questions.

2. Create a list of three to five factual questions. Your research will probably turn up some facts that you want your interviewee to confirm or challenge.

3. Create a list of five to ten open-ended questions. Write down five to ten questions that cannot be answered with a simple “yes” or “no.” Your questions should urge the interviewee to offer a detailed explanation or opinion.

4. Decide how you will record the interview. Do you want to record the interview as a video or make an audio recording? Or do you want to take written notes? Each of these methods has its pros and cons. For example, audio recording captures the whole conversation, but interviewees are often more guarded about their answers when they are being recorded.

5. Set up the interview. The best place to do an interview is at a neutral site, like a classroom, a room in the library, or perhaps a café. The second best place is at the interviewee’s office. If necessary, you can do interviews over the phone.

Conduct The Interview

1. Explain the purpose of your project. Start out by describing your project to the interviewee and describe how the information from the interview will be used. Also, tell the interviewee how long you expect the interview will take.

2. Ask permission to record. If you are recording the interview in any way, ask permission to make the recording. First, ask if recording is all right before you turn on your device. Then, once you start recording, ask again so you record the interviewee’s permission.

3. Ask your factual questions first. Warm up the interviewee by asking questions that allow him or her to confirm or deny the facts you have already collected.

4. Ask your open-ended questions next. Ask the interviewee about his or her opinions, feelings, experiences, and views about the topic.

5. Ask if he or she would like to provide any other information. Often people want to tell you things you did not expect or know about. You can wrap up the interview by asking, “Is there anything else you would like to add about this topic?”

6. Thank the interviewee. Don’t forget to thank the interviewee for his or her time and information.

Interview Follow-Up

1. Write down everything you remember. As soon as possible after the interview, describe the interviewee in your notes and fill out any details you couldn’t write down during the interview. Do this even if you recorded the interview.

2. Get your quotes right. Clarify any direct quotations you collected from your interviewee. If you aren’t sure whether you got something right, you might e-mail your quotes to the interviewee for confirmation.

3. Back-check the facts. If the interviewee said something that was new to you or that conflicted with your prior research, use electronic, online, or print sources to back-check the facts. If there is a conflict, you can send an e-mail to the interviewee asking for clarification.

4. Send a thank-you note. Usually, an e-mail that thanks your interviewee is sufficient, but you might also send a card or brief letter of thanks.

Using an Informal Survey

Informal surveys are especially useful for generating data and gathering the views of many different people on the same questions. Many free online services such as SurveyMonkey, Survey Gizmo, and Zoomerang allow you to create and distribute your own surveys. They will also collect and tabulate the results for you. Here is how to create a useful, though not a scientific, survey:

1. Identify the population you want to survey. Some surveys target specific kinds of people (e.g., college students, women from ages 18–22, medical doctors). Others are designed to be filled out by anyone.

2. Develop your questions. Create a list of five to ten questions that can be answered quickly. Surveys typically use four basic types of questions: rating scales, multiple-choice, numeric open-ended, and text open-ended.

3. Check your questions for neutrality. Make sure your questions are as neutral as possible. Don’t lead on the people you are surveying with biased or slanted questions that fit your own beliefs.

4. Pilot-test your questions for clarity. Make sure your questions won’t confuse your survey takers. Before distributing your survey, ask a classmate or friend to take it and watch as he or she answers the questions. If your test subject struggles to answer any questions, you probably need to clarify them.

5. Distribute the survey. Ask a number of people to complete your survey, and note the kinds of people who agree to do it. Not everyone will be interested in completing your survey, so remember that your results might reflect the views of specific kinds of people.

6. Tabulate your results. When your surveys are returned, convert any quantitative responses into data. In written answers, pull out phrases and quotes that seem to reflect how the people you surveyed felt about your topic.

Professional researchers could point out that your informal survey is not objective and that your results are not statistically valid. That’s fine, as long as you are not using your survey to make important decisions or support claims about how people really feel. Your informal survey will still give you some helpful information about the opinions of others.

Doing Field Observations

Conducting a field observation can help you generate ideas and confirm facts. Field observations involve watching something closely and taking detailed notes.

1. Choose an appropriate location (field site). You want to choose a field site that allows you to see as much as possible, while not making it obvious that you are watching and taking notes. People will typically change their behavior if they think someone is watching them.

2. Take notes in a two-column format. A good field note technique is to use two columns to record what you see. On the left side, list the people, things, and events you observed. On the right side, write down how you interpret what you observed.

3. Use the Five-W and How questions. Keep notes about the who, what, where, when, why, and how elements that you observe. Try to include as much detail as possible.

4. Use your senses. Take notes about the things you see, hear, smell, touch, and taste while you are observing.

5. Pay attention to things that are moving or changing. Take special note of the things that moved or changed while you were observing, and what caused them to do so.

When you are finished taking notes, spend some time interpreting what you observed. Look for patterns in your observations to help you make sense of your field site.

Sources that require an Internet connection and/or electronic device (computer, DVD player, radio, television, etc.) to access. For example: websites, podcasts, videos, movies, television shows, audio recordings.

A source written by experts in a particular field that serves to keep others interested in that field up to date on the most recent research, findings, and news (also called peer-reviewed or academic sources).

Sources that were originally intended to be accessed and read in physical, printed form. For example: books, newspapers, magazines, journals, newsletters, other periodicals or publications.

A structured set of data from multiple sources, usually accessible using a computer.

Source material that was collected by the researcher and analyzed for research purposes. For example: Personal experiences, field observations, interviews, surveys, case studies, experiments.