19

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Invent the content of your argument, showing the major sides fairly. (GEO 1, 4; SLO 1)

- Organize and draft your argument as an evenhanded debate. (GEO 2; SLO 1)

- Use a style that will set your side apart from the others. (GEO 1, 2; SLO 4)

- Design your argument to create a favorable impression. (GEO 2; SLO 4)

- Rebut and refute the arguments of others. (GEO 2; SLO 2)

Surely, you have heard the old saying, “There are always two sides to every argument.” This saying goes back two thousand years to the Greek rhetorician Protagoras. He wanted to remind people that no matter how certain they were about the truth of their side, someone could almost always come up with a reasonable argument that counters it. That’s why arguing can be fun—and a bit frustrating at times.

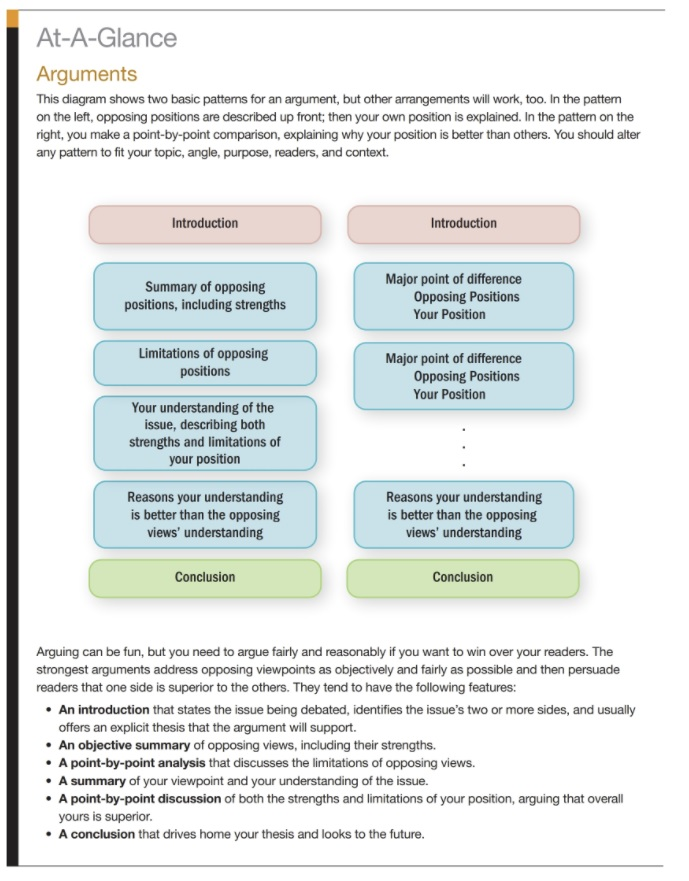

The purpose of an argument is to explore two or more sides of a controversial topic and then to argue fairly and reasonably for one side over the others. When you write an argument, you will deepen your own understanding of your position and sometimes even alter it. By fairly presenting all viewpoints, you will also strengthen your argument because readers will view you as fair-minded and knowledgeable.

This balanced approach is what makes argument papers different from commentaries, which usually express only the author’s opinion. An argument describes two or more opposing positions and discusses why one is stronger or better than the others.

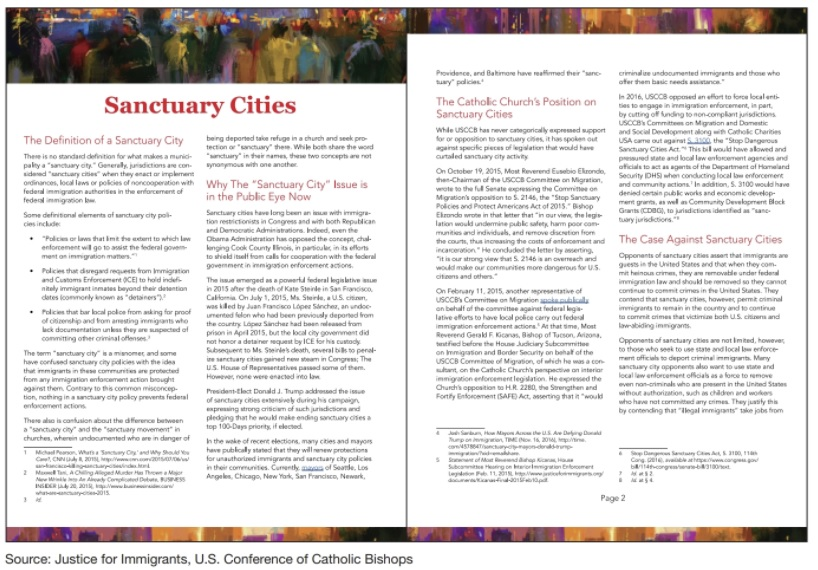

In college, your professors will ask you to write argument papers that analyze and evaluate the different sides of an issue and then argue for one side or another. For example, you might be asked to write argument papers that explore controversial topics like climate change, texting while driving, immigration policies, or the costs of a higher education. You will write argument papers that discuss historical events, philosophical positions, religion, and ethics.

In the workplace, arguments are often called “position papers”; these documents argue for or against business strategies or policies. Your supervisors will ask you to review the various sides of important issues and then express your own opinion on the best way to react or make progress.

The ability to argue effectively and persuasively is an essential skill that will help you throughout your life.

Inventing Your Argument’s Content

When writing an argument, you need to understand the issue as thoroughly as possible. But here is the hard part: you must present all major sides of the controversy in a fair way. In other words, when reading your argument, a person with an opposing viewpoint would say, “Yes, that’s a fair presentation of my views.”

Your goal is to sound respectful and reasonable. If your readers sense that you are distorting opposing positions or overlooking the weak points in your own position, they will question whether you are being fair and presenting the argument in an evenhanded way. So let your facts and reasoning do the talking for you. If your position is truly stronger, you should be able to explain all sides fairly and then demonstrate to your readers why your side is better.

Inquiring: Identifying Your Topic

When writing an argument, choose a topic (or question) that is narrow enough for you to manage, while allowing you to offer new insights. If you pick an overly broad or well-worn topic, such as gun control or abortion, you will find it difficult to say anything new or interesting. Instead, you should narrow your topic by asking what is new or what has changed about it recently.

Examples

Too Broad: Should we allow people to carry concealed handguns?

Better: Should students, faculty, and staff be allowed to carry concealed handguns on college campuses?

Even Better: Given the recent shooting at nearby Ridgeland University, should we allow students, faculty, and staff to carry concealed handguns on our college campus?

New topics for arguments are rare, but new angles on topics are readily available. Pay attention to what has changed about your topic or how recent events have made your topic important today.

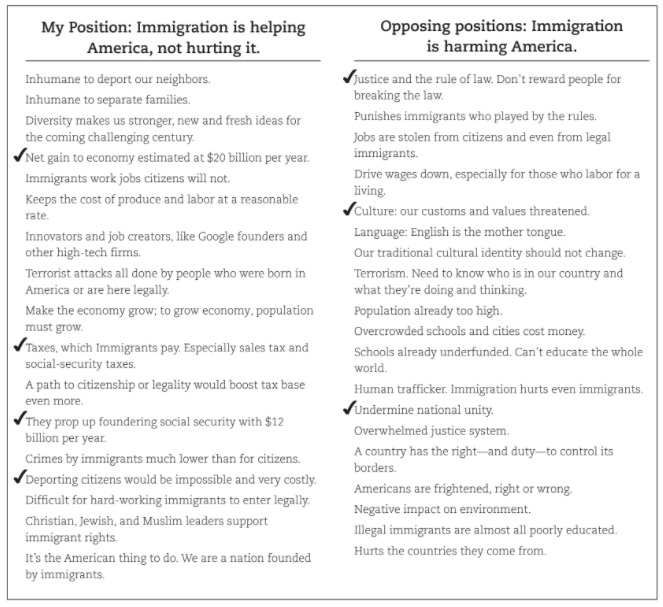

Inquiring: Identifying Points of Contention

To begin generating content for your argument, first identify the major points on which your side and opposing sides differ. A brainstorming list like the one shown in Figure 28.1 is often the best way to identify these major points. When brainstorming, use two columns. In the left column, write “My position” and list all the arguments you can think of to support your case. In the right column, write “Opposing positions” and list the best arguments for the other sides of the controversy. When listing the ideas of people who disagree with you, try to see things from their perspective. What are their strongest arguments? Why do others hold these views or values? What goals are they trying to achieve that are different from yours? When you have filled out your brainstorming lists, put checkmarks next to the two to five most important issues on which you disagree with the views of others. These are your argument’s “major points of contention.”

Researching: Finding Out What Others Believe and Why

You can use these major points of contention as a starting place for your research. Begin by researching the opposing viewpoints first. When you examine the beliefs of people who disagree with your position, you can identify the strengths and weaknesses of your own position. And, if necessary, you can shift your position as you become more informed about the issue.

While researching the other side, imagine that you believe their point of view. If you were on the other side, how would you build your argument? Which points would be strongest? What weaknesses would you point out in the other sides’ positions? What kinds of sources would you use to support these positions? Your goal is to figure out why people hold viewpoints different from yours.

Then find sources that support your position. Your research on other viewpoints should help you pinpoint the kinds of sources that will support your side of and answer the criticisms that individuals holding opposing positions might use against you.

Keep in mind that using a variety of sources will make your argument stronger. So you should look for a mix of online, print, and empirical sources that support all sides of the issue.

- Online sources. The Internet can be helpful for generating content, but you need to be especially careful about your sources when you are preparing to write an argument. Countless people will offer their opinions on blogs and Web sites, but these sources are often heavily biased and may not back up their opinions with valid sources. When researching, you should look for trustworthy sources on the Internet and avoid sources that are too biased. Also, keep an eye out for credible television documentaries and radio broadcasts on your subject, because they will often address both sides of the issue in a journalistic way.

- Print sources. Print documents will likely be your most reliable sources for factual information. Look for magazines, academic journals, books, and other documents because these sources tend to be more reliably factual than online sources, and they usually have less bias. Through your library’s Web site, try using the Readers’ Guide to find magazine articles. Google Scholar is another good source that can point you toward scholarly articles available through your library. Use periodical indexes to find academic articles. Your library’s online catalog is a good place to search for books.

- Empirical sources. Facts you gather yourself will be useful for backing up your claims about your topic. Set up an interview with an expert on your topic. You might find it especially helpful to interview an expert who holds an opposing view. This kind of interview will help you understand both sides of the issue much better. You might create a survey that will help you generate your own data. You can also conduct field observations to study your topic in action. Remember, you are looking for information that is credible and not too biased. It is fine to use sources that make a strong argument for one side or the other, but you need to make sure these sources are backed up with facts, data, and solid sources.

Organizing and Drafting Your Argument

The key to organizing an argument is to remember that you need to treat all major sides of the issue fairly and thoroughly. As you are drafting your argument, imagine you are debating with another person or a group of people. If you were in a public debate, how would you express your best points and persuade the audience that yours is the most reasonable position? How would you respond to criticisms of your position? Meanwhile, try to really understand and explain the opposing perspectives while countering their best arguments.

Introduction

Your introduction should prepare readers for your argument. It will usually include some or all of these moves:

Start with a grabber or lead.

Look for a good grabber or lead to catch your readers’ attention at the beginning of the introduction.

Identify your topic.

State the controversial issue your argument will explore. You might express it as a question.

Offer background information.

Briefly provide an overview of the various positions on the issue.

State your purpose.

State your purpose clearly by telling readers that you will explain all sides of the issue and demonstrate why your position is stronger.

State your main point or thesis.

State your main point or thesis clearly and completely. In most arguments, the main point or thesis statement typically appears at the end of your introduction. In some situations, you will want to save your main point or thesis statement for the conclusion, especially if you think readers might resist your argument. Your main point or thesis statement should be as specific and thorough as possible.

Examples

Weak: Only qualified police officers should be allowed to carry weapons on campus.

Stronger: Only qualified police officers should be allowed to carry weapons on campus, because the dangers of allowing students and faculty to carry weapons clearly outweigh the slight chance that a concealed weapon would be used in self-defense.

Summary and Limitations of Opposing Positions

The body of an argument usually begins by explaining the other side or sides of the issue. Try to explain the opposing argument in a way that your readers would consider fair, reasonable, and complete. Acknowledge its strong points. Where possible, use quotes from opposing arguments to explain the other side’s views. Paraphrasing or summarizing their argument is fine too, as long as you do it fairly. Then, as objectively as possible, explain the limitations of the opposing positions.

What exactly are they missing? What have they neglected to consider? What are they ignoring in their argument? Because you want to highlight these limitations as fairly as possible, this is not the place to be sarcastic or dismissive. You want to point out the weaknesses in your opponents’ argument in a straightforward way.

Your Understanding of the Issue

Now it’s your turn. Explain your side of the argument by walking your readers through the two to five major points of contention, showing them why your side of the argument is stronger. Here is where you need to use your sources to back up your argument. You must use good reasoning, examples, facts, and data to show readers why your opinion is more credible.

Reasons Your Understanding Is Stronger

Before moving to your conclusion, you might spend some time comparing and contrasting the opposing views with your own. Briefly, compare the two sides head to head, showing readers why your view is stronger. At this point, it is all right to concede some points to your opponents. Your goal is to show your readers that your view is stronger on balance. In other words, both sides probably have their strengths and weaknesses. You want to show that your side has more strengths and fewer weaknesses than the opposing side.

Conclusion

Bring your argument to a close by stating or restating your thesis and looking to the future. Here is where you should drive home your main point or thesis by telling your readers exactly what you believe. Then show how your position leads to a better outcome. Overall, your conclusion should be brief (a paragraph in most arguments).

Choosing an Appropriate Style

The style of your argument will help you distinguish your side from opposing sides. Even though your goal is to be factually fair to all sides, there is nothing wrong with using style to make your side sound more appealing and exciting.

Use Plain Style to Describe the Opposing Positions

When dealing with opposing perspectives, you should not be sarcastic or dismissive. Instead, describe opposing arguments as plainly as possible. You will also find techniques for writing better paragraphs that use clear topic sentences. Using these plain style techniques to describe opposing perspectives conveys fairness and objectivity.

Use Similes, Metaphors, and Analogies

When Describing Your Position When you are describing your side of the argument, you want to present your case in ways that will be visual and memorable. By using similes, metaphors, and analogies, you can help your readers visualize your argument and remember its key points.

Simile (X Is Like Y)

A college campus in which students carry guns would be like a tense Old West frontier town.

Downloading a movie is like borrowing a book from a library, not pirating a ship on the high seas.

Metaphor (X Is Y)

If a shooting incident did occur, the classroom could turn into a deadly crossfire zone, with armed students and police firing away at anyone with a gun in his or her hand. No one would be able to tell the difference between the “bad guy” and students who are defending themselves with their weapons drawn.

The purpose of the movie industry’s lawsuits is to throw a few unfortunate college students to the lions. That way, they can hold up some bloody carcasses to scare the rest of us.

Analogy (X Is to Y Like A Is to B)

For some people, a gun has the same comforting effect as a safety blanket to a baby. Neither a gun nor a blanket will protect you from those imaginary monsters, but both can give you an imaginary feeling of security.

The movie industry’s lawsuits are like your old Aunt Martha defending her tin of chocolate chip cookies at the church potluck. The industry offers a plate of delicious films, but only the “right people” are allowed to enjoy them. College students aren’t the right people because we don’t have enough money.

Try some of these “persuasive style” techniques to enhance the power of your argument. Similes, metaphors, and analogies will make your writing more visual and colorful, and they will also help you come up with new ways to think and talk about your topic.

Use Top-Down Paragraphs

Your argument needs to sound confident, and your readers should be able to find your major points easily. So, in your paragraphs, put each major point in the first or second sentence. Don’t hide your major points in the middle of paragraphs where your readers can’t find them easily. A top-down style will make you sound more confident because you are stating your major claims and then backing them up with solid reasoning and evidence.

Define Unfamiliar Terms

Your readers may or may not be familiar with the topic of your argument. So if you use any specialized or technical terms, provide quick parenthetical or sentence definitions to explain them.

Sentence Definition

A conceal-carry permit is the legal authorization that allows private citizens to carry a handgun or other weapon on their person or in a secure place nearby. Peer-to-peer file sharing involves using a network of computers to store and share files without charge.

Parenthetical Definitions

Colleges have traditionally invoked an “opt-out” statute, a law that allows the ban of weapons where posted, to keep concealed handguns off their campuses. Movie sharing should become illegal when a person commodifies the files (i.e., sells them on a flash drive, recordable DVD, or Web site).

Position Paper Example #1: “Concussions in Ice Hockey: Is It Time to Worry?” by Khizer Amin (Student Essay)

Position Paper Example #2: “To Ban or Not To Ban” (MLA Style)

Position Paper Example #3: “The Case for Censoring Hate Speech” by Sean McElwee

For the past few years speech has moved online, leading to fierce debates about its regulation. Most recently, feminists have led the charge to purge Facebook of misogyny that clearly violates its hate speech code. Facebook took a small step two weeks ago, creating a feature that will remove ads from pages deemed “controversial.” But such a move is half-hearted; Facebook and other social networking Web sites should not tolerate hate speech and, in the absence of a government mandate, adopt a European model of expunging offensive material. Stricter regulation of Internet speech will not be popular with the libertarian-minded citizens of the United States, but it’s necessary. A typical view of such censorship comes from Jeffrey Rosen, who argues in The New Republic that,

given their tremendous size and importance as platforms for free speech, companies like Facebook, Google, Yahoo!, and Twitter shouldn’t try to be guardians of what Waldron calls a “well-ordered society”; instead, they should consider themselves the modern version of Oliver Wendell Holmes’s fractious marketplace of ideas—democratic spaces where all values, including civility norms, are always open for debate.

This image is romantic and lovely (although misattributed to Oliver Wendell Holmes, who

famously toed both lines on the free speech debate, instead of John Stuart Mill) but it’s worth asking what this actually looks like. Rosen forwards one example:

Last year, after the French government objected to the hash tag “#unbonjuif”—intended to inspire hateful riffs on the theme “a good Jew . . .”—Twitter blocked a handful of the resulting tweets in France, but only because they violated French law. Within days, the bulk of the tweets carrying the hashtag had turned from anti-Semitic to denunciations of anti-Semitism, confirming that the Twittersphere is perfectly capable of dealing with hate speech on its own, without heavy-handed intervention.

It’s interesting to note how closely this idea resembles free market fundamentalism: simply get rid of any coercive rules and the “marketplace of ideas” will naturally produce the best result. Humboldt State University compiled a visual map that charts 150,000 hateful insults aggregated over the course of 11 months in the U.S. by pairing Google’s Maps API with a series of the most homophobic, racist, and otherwise prejudiced tweets. The map’s existence draws into question the notion that the “twittersphere” can organically combat hate speech; hate speech is not going to disappear from Twitter on its own.

The negative impacts of hate speech do not lie in the responses of third-party observers, as hate speech aims at two goals. First, it is an attempt to tell bigots that they are not alone. Frank Collins—the neo-Nazi prosecuted in National Socialist Party of America v. Skokie (1977)—said, “We want to reach the good people, get the fierce anti-Semites who have to live among the Jews to come out of the woodwork and stand up for themselves.”

The second purpose of hate speech is to intimidate the targeted minority, leading them to question whether their dignity and social status is secure. In many cases, such intimidation is successful. Consider the number of rapes that go unreported. Could this trend possibly be impacted by Reddit threads like /r/rapingwomen or /r/mensrights? Could it be due to the harassment women face when they even suggest the possibility they were raped? The rape culture that permeates Facebook, Twitter, and the public dialogue must be held at least partially responsible for our larger rape culture.

Reddit, for instance, has become a veritable potpourri of hate speech; consider Redditthreads like /r/nazi, /r/killawoman, /r/misogny, /r/killingwomen. My argument is not that these should be taken down because they are offensive, but rather because they amount to the degradation of a class that has been historically oppressed. Imagine a Reddit thread for /r/lynchingblacks or /r/assassinatingthepresident. We would not argue that we should sit back and wait for this kind of speech to be “outspoken” by positive speech, but that it should be entirely banned.

American free speech jurisprudence relies upon the assumption that speech is merely the extension of a thought, and not an action. If we consider it an action, then saying that we should combat hate speech with more positive speech is an absurd proposition; the speech has already done the harm, and no amount of support will defray the victim’s impression that they are not truly secure in this society. We don’t simply tell the victim of a robbery, “Hey, it’s okay, there are lots of other people who aren’t going to rob you.” Similarly, it isn’t incredibly useful to tell someone who has just had their race/gender/sexuality defamed, “There are a lot of other nice people out there.”

Those who claim to “defend free speech” when they defend the right to post hate speech online are, in truth, backwards. Free speech isn’t an absolute right; no right is weighed in a vacuum. The court has imposed numerous restrictions on speech. Fighting words, libel, and child pornography are all banned. Other countries merely go one step further by banning speech intended to intimidate vulnerable groups. The truth is that hate speech does not democratize speech; it monopolizes speech. Women, LGBTQ individuals, and racial or religious minorities feel intimidated and are left out of the public sphere. On Reddit, for example, women have left or changed their usernames to be more male-sound-ing lest they face harassment and intimidation for speaking on Reddit about even the most gender-neutral topics.

Those who try to remove this hate speech have been criticized from left and right. At Slate, Jillian York writes, “While the campaigners on this issue are to be commended for raising awareness of such awful speech on Facebook’s platform, their proposed solution is ultimately futile and sets a dangerous precedent for special interest groups looking to bring their pet issue to the attention of Facebook’s censors.”

It hardly seems right to qualify a group fighting hate speech as an “interest group” trying to bring their “pet issue” to the attention of Facebook censors. The “special interest” groups she fears might apply for protection must meet Facebook’s strict community standards, which state:

While we encourage you to challenge ideas, institutions, events, and practices, we do not permit individuals or groups to attack others based on their race, ethnicity, national origin, religion, sex, gender, sexual orientation, disability or medical condition.

If anything, the groups to which York refers are nudging Facebook toward actually enforcing its own rules.

People who argue against such rules generally portray their opponents as standing on a slippery precipice, tugging at the question, “What next?” We can answer that question: Canada, England, France, Germany, The Netherlands, South Africa, Australia, and India all ban hate speech. Yet, none of these countries have slipped into totalitarianism. In many ways, such countries are more free when you weigh the negative liberty to express harmful thoughts against the positive liberty that is suppressed when you allow for the intimidation of minorities.

As Arthur Schopenhauer said, “the freedom of the press should be governed by a very strict prohibition of all and every anonymity.” However, with the Internet, the public dialogue has moved online, where hate speech is easy and anonymous. Jeffrey Rosen argues that norms of civility should be open to discussion, but in today’s reality, this issue has already been decided; impugning someone because of their race, gender, or orientation is not acceptable in a civil society. Banning hate speech is not a mechanism to further this debate because the debate is over. As Jeremy Waldron argues, hate speech laws prevent bigots from, “trying to create the impression that the equal position of members of vulnerable minorities in a rights-respecting society is less secure than implied by the society’s actual foundational commitments.”

Some people argue that the purpose of laws that ban hate speech is merely to avoid offending prudes. No country, however, has mandated that anything be excised from the public square merely because it provokes offense, but rather because it attacks the dignity of a group—a practice the U.S. Supreme Court called in Beauharnais v. Illinois (1952) “group libel.” Such a standard could easily be applied to Twitter, Reddit and other social media Web sites. While Facebook’s policy as written should be a model, its enforcement has been shoddy. Chaim Potok argues that if a company claims to have a policy, it should rigorously and fairly enforce it.

If this is the standard, the Internet will surely remain controversial, but it can also be free of hate and allow everyone to participate. A true marketplace of ideas must co-exist with a multi-racial, multi-gender, multi-sexually-oriented society, and it can.

The broad idea or issue that a message deals with.

A question that a research project sets out to answer.

Sources that require an Internet connection and/or electronic device (computer, DVD player, radio, television, etc.) to access. For example: websites, podcasts, videos, movies, television shows, audio recordings.

Sources that were originally intended to be accessed and read in physical, printed form. For example: books, newspapers, magazines, journals, newsletters, other periodicals or publications.

Source material that was collected by the researcher and analyzed for research purposes. For example: Personal experiences, field observations, interviews, surveys, case studies, experiments.

A beginning section which states the purpose and goals of the following writing, generally followed by the body and conclusion. The introduction typically describes the scope of the document and gives the brief explanation or summary of the document.

The main idea, point, or claim of a written work. Plural: theses.

The last paragraph in an academic essay that generally summarizes the essay, presents the main idea of the essay, or gives an overall solution to a problem or argument given in the essay.

A figure of speech involving the comparison of one thing with another thing of a different kind, used to make a description more emphatic or vivid (e.g., as brave as a lion, crazy like a fox ).

A figure of speech in which a word or phrase is applied to an object or action to which it is not literally applicable.

A comparison of the relationship between two sets of things, typically for the purpose of explanation or clarification.