25

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Define and identify nouns, pronouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, conjunctions, prepositions, and articles. (SLO 1, 4, 5; GEO 1)

- Properly use the different parts of speech in a sentence. (SLO 1, 4, 5; GEO 1)

1. Nouns

Nouns are a diverse group of words, and they are very common in English. Nouns are a category of words defining things—people, places, items, concepts. The video below is a brief introduction to them and the role they play:

As we’ve just learned, a noun is the name of a person (Dr. Sanders), place (Lawrence, Kansas, factory, home), thing (scissors, saw, book), or idea (love, truth, beauty, intelligence). Let’s look at the following examples to get a better idea of how nouns work in sentences. All of the nouns have been bolded:

- The one experiment that has been given the most attention in the debate on saccharin is the 1977 Canadian study done on rats.

- The multi-fuel capacity of the Stirling engine gives it a versatility not possible in the internal combustion engine.

- The regenerative cooling cycle in the engines of the Space Shuttle is made up of high-pressure hydrogen that flows in tubes connecting the nozzle and the combustion chamber.

Of the many different categories of nouns, a couple deserve closer attention here.

Common vs. Proper Noun

Common nouns are generic words, like tissue. They are lower-cased (unless they begin a sentence). A proper noun, on the other hand, is the name of a specific thing, like the brand name Kleenex. Proper nouns are always capitalized.

- common noun: name

- proper noun: Ester

Concrete vs. Abstract Noun

Concrete nouns are things you can hold, see, or otherwise sense, like book, light, or warmth. Abstract nouns, on the other hand, are (as you might expect) abstract concepts, like time and love.

- concrete noun: rock

- abstract noun: justice

The rest of this section will dig into other types of nouns: count v. non-count nouns, compound nouns, and plural nouns.

Regular Plural Nouns

A plural noun indicates that there is more than one of that noun (while a singular noun indicates that there is just one of the noun). Most plural forms are created by simply adding an -s or –es to the end of the singular word. For example, there’s one dog (singular), but three dogs (plural). However, English has both regular and irregular plural nouns. Regular plurals follow this rule (and other similar rules), but irregular plurals are, well, not regular and don’t follow a “standard” rule.

Let’s start with regular plurals: regular plural nouns use established patterns to indicate there is more than one of a thing.

Recognize nouns marked with plural form –s.

As was mentioned earlier, we add the plural suffix –s to most words:

- cat → cats

- bear → bears

- zebra → zebras

However, after sounds s, z, sh, ch, and j, we add the plural suffix –es:

- class → classes

- sash → sashes

- fox → foxes

Some words that end in z also double their ending consonant, like quizzes.

After the letter o.

We also add the plural suffix –es to most words that end in o:

- potato → potatoes

- hero → heroes

- mosquito → mosquitoes

However, when the words have a foreign origin (e.g. Latin, Greek, Spanish), we just add the plural suffix –s

- taco → tacos

- avocado → avocados

- maestro → maestros

After –y and –f, –fe

When a word ends in y and there is a consonant before y, we change the y to i and add –es.

- sky → skies

- candy → candies

- lady → ladies

However, if the y follows another vowel, you simply add an –s.

- alloy → alloys

- donkey → donkeys

- day → days

When a word ends in –f or –fe, we change the f to v and add –es.

- leaf → leaves

- life → lives

- calf → calves

However, if there are two terminal fs or if you still pronounce the f in the plural, then you simply add an –s:

- cliff → cliffs

- chief → chiefs

- reef → reefs

Irregular Plural Nouns

Irregular plurals, unlike regular plurals, don’t necessarily follow any particular pattern—instead, they follow a lot of different patterns. Because of this, irregular plurals require a lot of memorization; you need to remember which nouns belong to which type of pluralization. Mastering irregulars uses a different region of your brain than regular pluralization: it’s an entirely different skill set than regular pluralization. So don’t get too frustrated if you can’t remember the correct plural. If you’re ever in doubt, the dictionary is there for you.

No Change (Base Plurals)

The first kind of irregular plural we’ll talk about is the no-change or base plural. In these words, the singular noun has the exact same form as the plural. Most no-change plurals are types of animals:

- sheep

- fish

- deer

- moose

Mid-Word Vowel Change

In a few words, the mid-word vowels are changed to form the plural. This video lists all seven of these words and their plurals.

Plural –en

And last we have plural –en. In these words –en is used as the plural ending instead of –s or -es.

- child → children

- ox → oxen

- brother → brethren

- sister → sistren

Borrowed Words

The last category of irregular plurals is borrowed words. These words are native to other languages (e.g., Latin, Greek) and have retained the pluralization rules from their original tongue.

Singular –us; Plural –i

- cactus → cacti

- fungus → fungi

- syllabus → syllabi

In informal speech, cactuses and funguses are acceptable. Octopuses is preferred to octopi, but octopi is an accepted word.

Singular -a; Plural –ae

- formula → formulae (sometimes formulas)

- vertebra → vertebrae

- larva → larvae

Singular –ix, –ex; Plural –ices, –es

- appendix → appendices (sometimes appendixes)

- index → indices

Singular –on, –um; Plural –a

- criterion → criteria

- bacterium → bacteria

- medium → media

Singular –is; Plural –es

- analysis → analyses

- crisis → crises

- thesis → theses

Count vs. Non-Count Nouns

A count noun (also countable noun) is a noun that can be modified by a numeral (three chairs) and that occurs in both singular and plural forms (chair, chairs). It can also be preceded by words such as a, an, or the (a chair). Quite literally, count nouns are nouns which can be counted.

A non-count noun (also mass noun), on the other hand, has none of these properties. It can’t be modified by a numeral (three furniture is incorrect), occur in singular/plural (furnitures is not a word), or co-occur with a, an, or the (a furniture is incorrect). Again, quite literally, non-count nouns are nouns which cannot be counted.

Example: Chair vs. Furniture

The sentence pairs below compare the count noun chair and the non-count noun furniture.

- There are chairs in the room. (correct)

- There are furnitures in the room. (incorrect)

- There is a chair in the room. (correct)

- There is a furniture in the room. (incorrect)

- There is chair in the room. (incorrect)

- There is furniture in the room. (correct)

- Every chair is man made. (correct)

- Every furniture is man made. (incorrect)

- All chair is man made. (incorrect)

- All furniture is man made. (correct)

- There are several chairs in the room. (correct)

- There are several furnitures in the room. (incorrect)

Determining the Type of Noun

In general, a count noun is going to be something you can easily count—like rock or dollar bill. Non-count nouns, on the other hand, would be more difficult to count—like sand or money. If you ever want to identify a singular non-count noun, you need a phrase beforehand—like a grain of sand or a sum of money.

Less, Fewer, Many, and Much

The adjectives less and fewer are both used to indicate a smaller amount of the noun they modify. Many and much are used to indicate a large amount of something. People often will use these pairs words interchangeably; however, the words fewer and many are used with count nouns, while less and much are used with non-count nouns:

- The pet daycare has fewer dogs than cats this week.

- Next time you make these cookies, you should use less sugar.

- Many poets struggle when they try to determine if a poem is complete or not.

- There’s too much goodness in her heart for her own good.

You may have noticed that much has followed the adverb too in this example (too much). This is because you rarely find much by itself. You don’t really hear people say things like “Now please leave me alone; I have much research to do.” The phrase “a lot of” has taken its place in current English: “I have a lot of research to do.” A lot of can be used in the place of either many or much:

- A lot of poets struggle when they try to determine if a poem is complete or not.

- There’s a lot of goodness in her heart for her own good.

Compound Nouns

A compound noun is a noun phrase made up of two nouns, e.g. bus driver, in which the first noun acts as a sort of adjective for the second one, but without really describing it.

For example, think about the difference between a black bird and a blackbird (Figure 37.1).

Compound nouns can be made up of two or more other words, but each compound has a single meaning. They may or may not be hyphenated, and they may be written with a space between words—especially if one of the words has more than one syllable, as in living room. In that regard, it’s necessary to avoid the oversimplification of saying that two single-syllable words are written together as one word. Thus, tablecloth but table mat, wine glass but wineglassful or key ring but keyholder. Moreover, there are cases which some people/dictionaries will write one way while others write them another way. Until very recently we wrote (the) week’s end, which later became weekend and then our beloved weekend.

Types of Compound Nouns

Short compounds may be written in three different ways:

- The solid or closed forms in which two usually moderately short words appear together as one. Solid compounds most likely consist of short units that often have been established in the language for a long time. Examples are housewife, lawsuit, wallpaper, basketball, etc.

- The hyphenated form in which two or more words are connected by a hyphen. This category includes compounds that contain suffixes, such as house-build(er) and single-mind(ed)(ness). Compounds that contain articles, prepositions or conjunctions, such as rent-a-cop and mother-of-pearl, are also often hyphenated.

- The open or spaced form consisting of newer combinations of usually longer words, such as distance learning, player piano, lawn tennis, etc.

Hyphens are often considered a squishy part of language (we’ll discuss this further in Hyphens and Dashes). Because of this, usage differs and often depends on the individual choice of the writer rather than on a hard-and-fast rule. This means open, hyphenated, and closed forms may be encountered for the same compound noun, such as the triplets container ship/container-ship/containership and particle board/particle-board/particleboard. If you’re ever in doubt whether a compound should be closed, hyphenated, or open, dictionaries are your best reference.

Plurals

The process of making compound nouns plural has its own set of conventions to follow. In all forms of compound nouns, we pluralize the chief element of a compound word (i.e., we pluralize the primary noun of the compound).

- fisherman → fishermen

- black bird → black birds

- brother-in-law → brothers-in-law

The word hand-me-down doesn’t have a distinct primary noun, so its plural is hand-me-downs.

2. Pronouns

Example

Did this paragraph feel awkward to you? Let’s try it again using pronouns:

Example

This second paragraph is much more natural. Instead of repeating nouns multiple times, we were able to use pronouns. You’ve likely hear the phrase “a pronoun replaces a noun”; this is exactly what a pronoun does. Because a pronoun is replacing a noun, its meaning is dependent on the noun that it is replacing. This noun is called the antecedent. Let’s look at the two sentences we just read again:

- Because a pronoun is replacing a noun, its meaning is dependent on the noun that it is replacing. This noun is called an antecedent.

There are two pronouns here: its and it. Its and it both have the same antecedent: “a pronoun.” Whenever you use a pronoun, you must also include its antecedent. Without the antecedent, your readers (or listeners) won’t be able to figure out what the pronoun is referring to. Let’s look at a couple of examples:

- Jason likes it when people look to him for leadership.

- Trini brushes her hair every morning.

- Billy often has to clean his glasses.

- Kimberly is a gymnast. She has earned several medals in different competitions.

So, what are the antecedents and pronouns in these sentences?

- Jason is the antecedent for the pronoun him.

- Trini is the antecedent for the pronoun her.

- Billy is the antecedent for the pronoun his.

- Kimberly is the antecedent for the pronoun she.

There are several types of pronouns, including personal, demonstrative, indefinite, and relative pronouns. The next few pages will cover each of these.

Personal Pronouns

Personal pronouns are what most people think of when they see the word pronoun. Personal pronouns include words like he, she, and they. The following sentences give examples of personal pronouns used with antecedents (remember, an antecedent is the noun that a pronoun refers to!):

- That man looks as if he needs a new coat. (the noun phrase that man is the antecedent of he)

- Kat arrived yesterday. I met her at the station. (Kat is the antecedent of her)

- When they saw us, the lions began roaring (the lions is the antecedent of they)

- Adam and I were hoping no one would find us. (Adam and I is the antecedent of us)

Pronouns may be classified by three categories: person, number, and case.

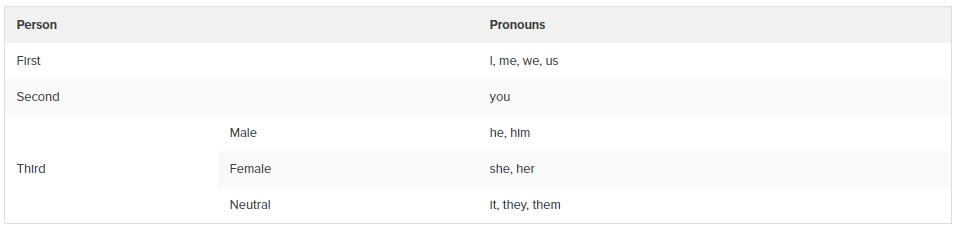

Person

Person refers to the relationship that an author has with the text that he or she writes, and with the reader of that text. English has three persons (first, second, and third):

First-person is the speaker or writer him- or herself. The first person is personal.

Second-person is the person who is being directly addressed. The speaker or author is saying this is about you, the listener or reader.

Third-person is the most common person used in academic writing. The author is saying this is about other people. In the third person singular there are distinct pronoun forms for male, female, and neutral gender.

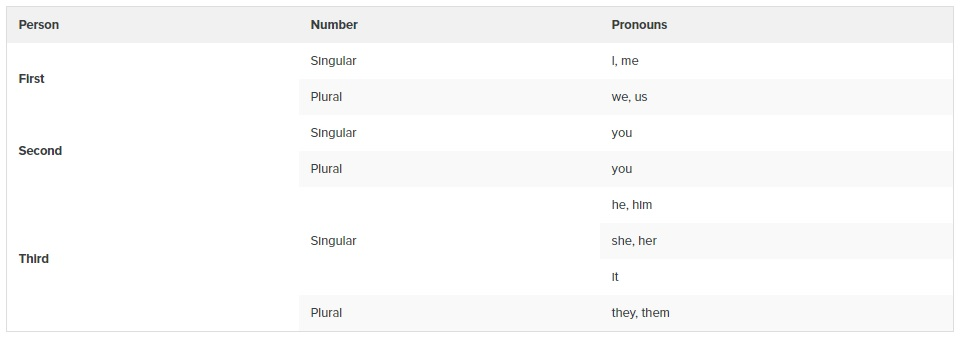

Number

There are two numbers: singular and plural. As we learned in nouns, singular words refer to only one a thing while plural words refer to more than one of a thing (I stood alone while they walked together).

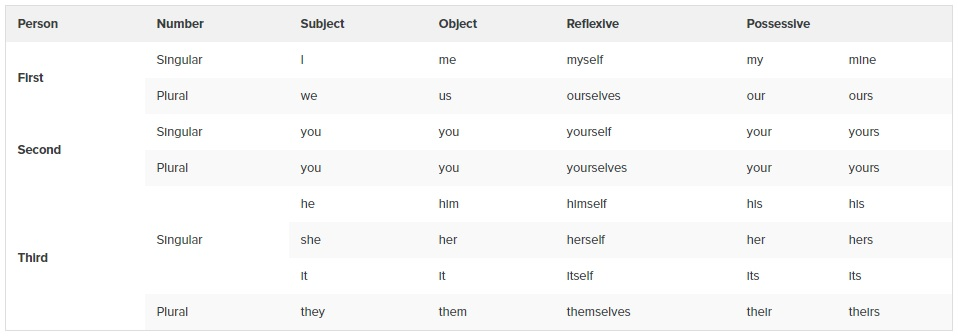

Case

English personal pronouns have two cases: subject and object (there are also possessive pronouns, which we’ll discuss next). Subject-case pronouns are used when the pronoun is doing the action. (I like to eat chips, but she does not). Object-case pronouns are used when something is being done to the pronoun (John likes me but not her). This video will further clarify the difference between subject- and object-case:

Reflexive Pronouns

Reflexive pronouns are a kind of pronoun that is used when the subject and the object of the sentence are the same.

- Jason hurt himself. (Jason is the antecedent of himself)

- We were teasing each other. (we is the antecedent of each other)

This is true even if the subject is only implied, as in the sentence “Don’t hurt yourself.” You is the unstated subject of this sentence. Watch this video:

Possessive Pronous

Possessive pronouns are used to indicate possession (in a broad sense). Some occur as independent phrases: mine, yours, hers, ours, yours, theirs. For example, “Those clothes are mine.” Others must be accompanied by a noun: my, your, her, our, your, their, as in “I lost my wallet.” His and its can fall into either category, although its is nearly always found in the second.

Both types replace possessive noun phrases. As an example, “Their crusade to capture our attention” could replace “The advertisers’ crusade to capture our attention.”

This video provides another explanation of possessive pronouns:

The table below includes all of the personal pronouns in the English language. They are organized by person, number, and case:

Demonstrative Pronouns

Demonstrative pronouns substitute for things being pointed out. They include this, that, these, and those. This and that are singular; these and those are plural.

The difference between this and that and between these and those is a little more subtle. This and these refer to something that is “close” to the speaker, whether this closeness is physical, emotional, or temporal. That and those are the opposite: they refer to something that is “far.”

- Do I actually have to read all of this?

- The speaker is indicating a text that is close to her, by using “this.”

- That is not coming anywhere near me.

- The speaker is distancing himself from the object in question, which he doesn’t want to get any closer. The far pronoun helps indicatethat.

- You’re telling me you sewed all of these?

- The speaker and her audience are likely looking directly at the clothes in question, so the close pronoun is appropriate.

- Those are all gross.

- The speaker wants to remain away from the gross items in question, by using the far “those.”

These pronouns are often combined with a noun. When this happens, they act as a kind of adjective instead of as a pronoun.

- Do I actually have to read all of this contract?

- That thing is not coming anywhere near me.

- You’re telling me you sewed all of these dresses?

- Those recipes are all gross.

The antecedents of demonstrative pronouns (and sometimes the pronoun it) can be more complex than those of personal pronouns:

- Animal Planet’s puppy cam has been taken down for maintenance. I never wanted this to happen.

- I love Animal Planet’s panda cam. I watched a panda eat bamboo for half an hour. It was amazing.

In the first example, the antecedent for this is the concept of the puppy cam being taken down. In the second example, the antecedent for it in this sentence is the experience of watching the panda. That antecedent isn’t explicitly stated in the sentence, but comes through in the intention and meaning of the speaker.

Indefinite Pronouns

Indefinite pronouns can be used in a couple of different ways:

- They can refer to members of a group separately rather than collectively. (To each his or her own.)

- They can indicate the non-existence of people or things. (Nobody thinks that.)

- They can refer to a person, but are not specific as to first, second or third person in the way that the personal pronouns are. (One does not clean one’s own windows.)

All of these pronouns are singular. The most common indefinite pronouns are: anybody, anyone, anything, each, either, every, everybody, everyone, everything, neither, no one, nobody, nothing, nobody else, somebody, someone, something, and one.

Sometimes third-person personal pronouns are sometimes used without antecedents—this applies to special uses such as dummy pronouns and generic they, as well as cases where the referent is implied by the context.

- You know what they say.

- It’s a nice day today.

Look back at the example “To each his or her own.” Saying “To each their own” would be incorrect, since their is a plural pronoun and each is singular. We’ll discuss this in further depth in Antecedent Agreement.

Relative Pronouns

There are five relative pronouns in English: who, whom, whose, that, and which. These pronouns are used to connect different clauses together. For example:

- Belen, who had starred in six plays before she turned seventeen, knew that she wanted to act on Broadway someday.

- The word who connects the phrase “had starred in six plays before she turned seventeen” to the rest of the sentence.

- My daughter wants to adopt the dog that doesn’t have a tail.

- The word that connects the phrase “doesn’t have a tail” to the rest of the sentence.

These pronouns behave differently from the other categories we’ve seen. However, they are pronouns, and it’s important to learn how they work.

Two of the biggest confusions with these pronouns are that vs. which and who vs. whom. The two following videos help with these:

That vs. Which

Who vs. Whom

Antecedent Clarity

We’ve already defined an antecedent as the noun (or phrase) that a pronoun is replacing. The phrase “antecedent clarity” simply means that is should be clear who or what the pronoun is referring to. In other words, readers should be able to understand the sentence the first time they read it—not the third, forth, or tenth. We’ll look at some examples of common mistakes that can cause confusion, as well as ways to fix each sentence.

Let’s take a look at our first sentence:

- Rafael told Matt to stop eating his cereal.

When you first read this sentence, is it clear if the cereal Rafael’s or Matt’s? Is it clear when you read the sentence again? Not really, no. Since both Rafael and Matt are singular, third person, and masculine, it’s impossible to tell whose cereal is being eaten (at least from this sentence).

How would you best revise this sentence?

Possible Revisions

- Let’s assume the cereal is Rafael’s:

- Rafael told Matt to stop eating Rafael’s cereal.

- Matt was eating Rafael’s cereal. Rafael told him to stop it.

- What if the cereal is Matt’s?:

- Rafael told Matt to stop eating Matt’s cereal.

- Matt was eating his own cereal when Rafael told him to stop.

These aren’t the only ways to revise the sentence. However, each of these new sentences has made it clear whose cereal it is.

Were those revisions what you expected them to be?

Let’s take a look at another example:

- Zuly was really excited to try French cuisine on her semester abroad in Europe. They make all sorts of delicious things.

When you read this example, is it apparent who the pronoun they is referring to? You may guess that they is referring to the French—which is probably correct. However, this is not actually stated, which means that there isn’t actually an antecedent. Since every pronoun needs an antecedent, the example needs to be revised to include one.

How would you best revise this sentence?

Possible Revisions

- Let’s assume that is is the French who make great cuisine:

- Zuly was really excited to try French cuisine on her semester abroad in Europe. The French make all sorts of delicious things.

- Zuly was really excited to try the cuisine in France on her semester abroad in Europe. The French make all sorts of delicious things.

- Zuly was really excited to try French cuisine on her semester abroad in Europe. The people there make all sorts of delicious things.

- One of the things Zuly was really excited about on her semester abroad in Europe was trying French cuisine. It comprises all sorts of delicious things.

As you write, keep these two things in mind:

- Make sure your pronouns always have an antecedent.

- Make sure that it is clear what their antecedents are.

Antecedent Agreement

As you write, make sure that you are using the correct pronouns. When a pronoun matches the person and number of its antecedent, we say that it agrees with its antecedent. Let’s look at a couple of examples:

- I hate it when Zacharias tells me what to do. He‘s so full of himself.

- The Finnegans are shouting again. I swear you could hear them from across town!

In the first sentence, Zacharias is singular, third person, and masculine. The pronouns he and himself are also singular, third person, and masculine, so they agree. In the second sentence, the Finnegans is plural and third person. The pronoun them is also plural and third person.

When you select your pronoun, you also need to ensure you use the correct case of pronoun. Remember we learned about three cases: subject, object, and possessive. The case of your pronoun should match its role in the sentence. For example, if your pronoun is doing an action, it should be a subject:

- He runs every morning.

- I hate it when she does this.

However, when something is being done to your pronoun, it should be an object:

- Birds have always hated me.

- My boss wanted to talk to him.

- Give her the phone and walk away.

However, things aren’t always this straightforward. Let’s take a look at some examples where things are a little more confusing.

- Some of the trickiest agreements are with indefinite pronouns:

- Every student should do his or her best on this assignment.

- If nobody lost his or her scarf, then where did this come from?

As we learned earlier in this outcome, words like every and nobody are singular, and demand singular pronouns. Here are some of the words that fall into this category: anybody, anyone, anything, each, either, every, everybody, everyone, everything, neither, no one, nobody, nothing, one, somebody, someone, and something.

Some of these may feel “more singular” than others, but they all are technically singular. Thus, using “he or she” is correct (while they is incorrect).

However, as you may have noticed, the phrase “he or she” (and its other forms) can often make your sentences clunky. When this happens, it may be best to revise your sentences to have plural antecedents. Because “he or she” is clunky, you’ll often see issues like this:

The way each individual speaks can tell us so much about him or her. It tells us what groups they associate themselves with, both ethnically and socially.

As you can see, in the first sentence, him or her agrees with the indefinite pronoun each. However, in the second sentence, the writer has shifted to the plural they, even though the writer is talking about the same group of people. When you write, make sure your agreement is correct and consistent.

Some of the most common pronoun mistakes occur with the decision between “you and I” and “you and me.”

People will often say things like “You and me should go out for drinks.” Or—thinking back on the rule that it should be “you and I”—they will say “Susan assigned the task to both you and I.” However, both of these sentences are wrong. Remember that every time you use a pronoun you need to make sure that you’re using the correct case.

Let’s take a look at the first sentence: “You and me should go out for drinks.” Both pronouns are the subject of the sentence, so they should be in subject case: “You and I should go out for drinks.”

In the second sentence (Susan assigned the task to both you and I), both pronouns are the object of the sentence, so they should be in object case: “Susan assigned the task to both you and me.”

3. Verbs

From 2002 to 2006, The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) ran a media campaign entitled “Verb: It’s What You Do.” This campaign was designed to help teens get and stay active, but it also provided a helpful soundbite for defining verbs: “It’s what you do.”

From 2002 to 2006, The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) ran a media campaign entitled “Verb: It’s What You Do.” This campaign was designed to help teens get and stay active, but it also provided a helpful soundbite for defining verbs: “It’s what you do.”

Verbs are often called the “action” words of language. As we discuss verbs, we will learn that this isn’t always the case, but it is a helpful phrase to remember just what verbs are.

Traditionally, verbs are divided into three groups: active verbs (these are “action” words), linking verbs, and helping verbs (these two types of verbs are not “action” words). In this outcome, we’ll discuss all three of these groups. We’ll also learn how verbs work and how they change to suit the needs of a speaker or writer.

Active Verbs

Active verbs are the simplest type of verb: they simply express some sort of action. Watch this video introduction to verbs:

Let’s look at the example verbs from the video one more time:

- contain

- roars

- runs

- sleeps

All of these verbs are active verbs: they all express an action.

Transitive and Intransitive Verbs

Active verbs can be divided into two categories: transitive and intransitive verbs. A transitive verb is a verb that requires one or more objects. This contrasts with intransitive verbs, which do not have objects.

It might be helpful to think of it this way: transitive verbs have to be done to something or someone in the sentence. Intransitive verbs only have to be done by someone.

Let’s look at a few examples of transitive verbs:

- We are going to need a bigger boat.

- The object in this sentence is the phrase “a bigger boat.” Consider how incomplete the thought would be if the sentence only said “We are going to need.” Despite having a subject and a verb, the sentence is meaningless without the object phrase.

- She hates filling out forms.

- Again, leaving out the object would cripple the meaning of the sentence. We have to know that forms is what she hates filling out.

- Hates is also a transitive verb. Without the phrase “filling out forms,” the phrase “She hates” doesn’t make any sense.

- Sean hugged his brother David.

- You can see the pattern. . . . Hugged in this sentence is only useful if we know who Sean squeezed. David is the object of the transitive verb.

Intransitive verbs, on the other hand, do not take an object.

- John sneezed loudly.

- Even though there’s another word after sneezed, the full meaning of the sentence is available with just the subject John and the verb sneezed: “John sneezed.” Therefore, sneezed is an intransitive verb. It doesn’t have to be done to something or someone.

- My computer completely died.

- Again, died here is enough for the sentence to make sense. We know that the computer (the subject) is what died.

This video provides a more in-depth explanation of transitive and intransitive verbs and how they work:

Intransitive

- The fire has burned for hundreds of years.

- Don’t let the engine stop running!

- The vase broke.

- Does your dog bite?

- Water evaporates when it’s hot.

Transitive

- Miranda burned all of her old school papers.

- Karl ran the best horse track this side of the river.

- She broke the toothpick.

- The cat bit him.

- Heat evaporates water.

Multi-word verbs a subclass of active verbs. They are made up of multiple words, as you might have guessed. They include things like stirfry, kickstart, and turn in. Multi-word verbs often have a slightly different meaning than their base parts. Take a look at the difference between the next two sentences:

- Ben carried the boxes out of the house.

- Ben carried out the task well.

The first sentence uses a single word verb (carried) and the preposition out. If you remove the preposition (and its object), you get “Ben carried the boxes,” which makes perfect sense. In the second sentence, carried out acts as a single entity. If you remove out, the sentence has no meaning: “Ben carried the task well” doesn’t make sense.

Let’s look at another example:

- She’s been shut up in there for years.

- Dude, shut up.

Can you see how the same principles apply here? Other multi-word verbs include find out, make off with, turn in, and put up with.

Linking Verbs

A linking verb is a verb that links a subject to the rest of the sentence. There isn’t any “real” action happening in the sentence. Sentences with linking verbs become similar to math equations. The verb acts as an equal sign between the items it links. Watch this video online:

As the video establishes, to be verbs are the most common linking verbs (is, are, was, were, etc.). David and the bear establish that there are other linking verbs as well. Here are some illustrations of other common linking verbs:

- Over the past five days, Charles has become a new man.

- It’s easy to reimagine this sentence as “Over the past five days, Charles = a new man.”

- Since the oil spill, the beach has smelled bad.

- Similarly, one could also read this as “Since the oil spill, the beach = smelled bad.”

- That word processing program seems adequate for our needs.

- Here, the linking verb is slightly more nuanced than an equals sign, though the sentence construction overall is similar. (This is why we write in words, rather than math symbols, after all!)

- This calculus problem looks difficult.

- With every step Jake took, he could feel the weight on his shoulders growing.

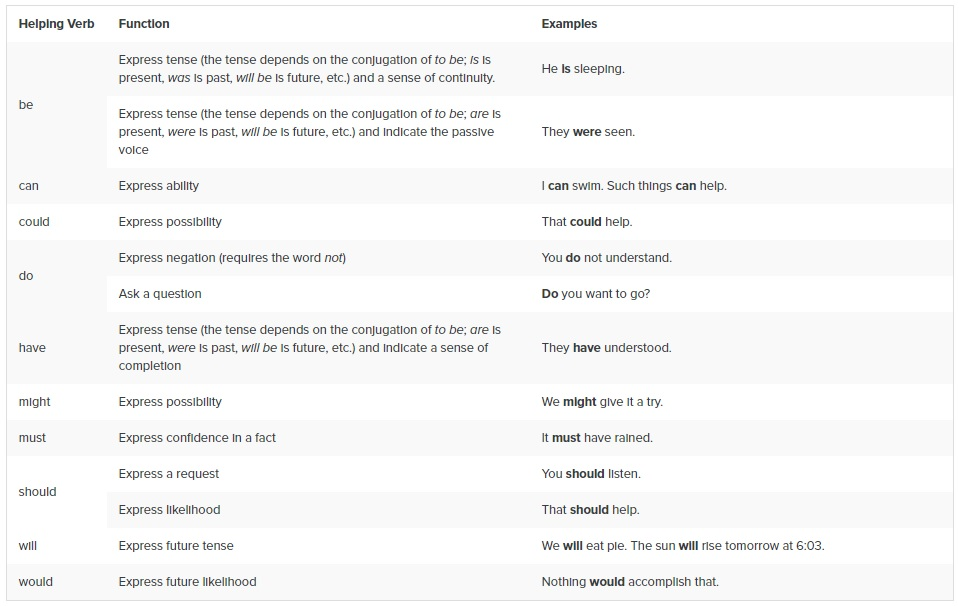

Helping Verbs

Helping verbs (sometimes called auxiliary verbs) are, as the name suggests, verbs that help another verb. They provide support and add additional meaning. Here are some examples of helping verbs in sentences:

- Mariah is looking for her keys still.

- Kai had checked the weather three times already, but he looked one more time to see if the forecast had changed.

- Whatever happens, do not let the water level drop below this line.

As you just saw, helping verbs are usually pretty short, and they include things like is, had, and do (we’ll look at a more complete list later). Let’s look at some more examples to examine exactly what these verbs do. Take a look at the sentence “I have finished my dinner.” Here, the main verb is finish, and the helping verb have helps to express tense. Let’s look at two more examples:

- By 1967, about 500 U.S. citizens had received heart transplants.

- While received could function on its own as a complete thought here, the helping verb had emphasizes the distance in time of the date in the opening phrase.

- Do you want tea?

- Do is a helping verb accompanying the main verb want, used here to form a question.

- Researchers are finding that propranolol is effective in the treatment of heartbeat irregularities.

- The helping verb are indicates the present tense, and adds a sense of continuity to the verb finding.

- He has given his all.

- Has is a helping verb used in expressing the tense of given.

The following table provides a short list of some verbs that can function as helping verbs, along with examples of the way they function. A full list of helping verbs can be found here.

The negative forms of these words (can’t, don’t, won’t, etc.) are also helping verbs.

Verb Tenses

What is tense? There are three standard tenses in English: past, present, and future. All three of these tenses have simple and more complex forms. For now we’ll just focus on the simple present (things happening now), the simple past (things that happened before), and the simple future (things that will).

Present Tense

Watch this quick introduction to the present tense:

Past Tense

Watch this quick introduction to the past tense:

Future Tense

Watch this quick introduction to the future tense:

Note: You may have noticed that in the present tense video, David talked about “things that are happening right now” and that he mentioned there were other ways to create the past and future tense. We’ll discuss these in further depth later in this chapter.

Conjugation

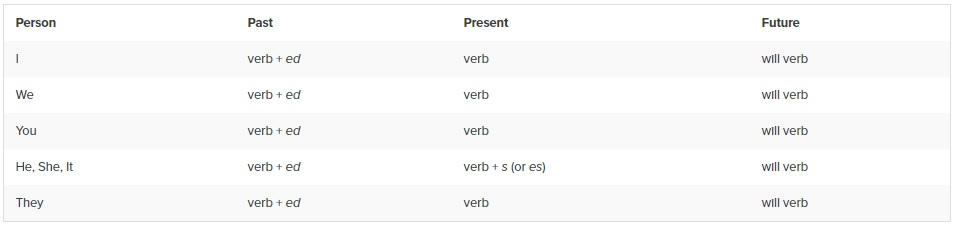

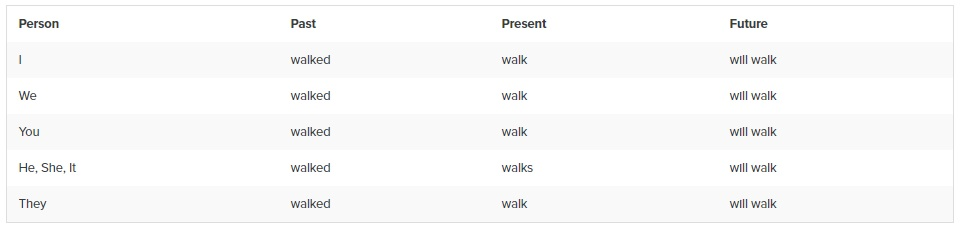

Most verbs will follow the pattern that we just learned in the previous videos:

To Walk

Let’s look at the verb to walk for an example:

Irregular Verbs

There are a lot of irregular verbs. Unfortunately, there’s a lot of memorization involved in keeping them straight.

This video shows a few of the irregular verbs you’ll have to use the most often (to be, to have, to do, and to say):

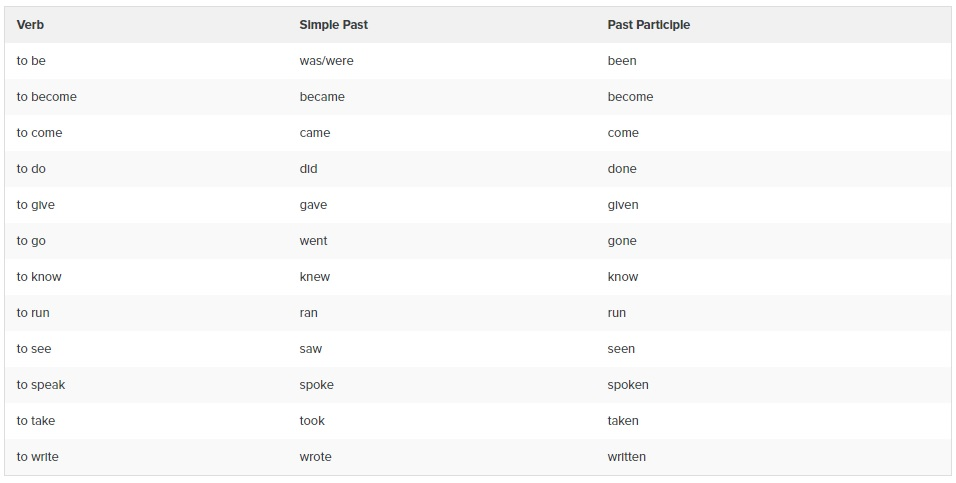

Here’s a list of several irregular past tense verbs.

Subject-Verb Agreement

The basic idea behind sentence agreement is pretty simple: all the parts of your sentence should match (or agree). Verbs need to agree with their subjects in number (singular or plural) and in person (first, second, or third). In order to check agreement, you simply need to find the verb and ask who or what is doing the action of that verb.

Person

Agreement based on grammatical person (first, second, or third person) is found mostly between verb and subject. For example, you can say “I am” or “he is,” but not “I is” or “he am.” This is because the grammar of the language requires that the verb and its subject agree in person. The pronouns I and he are first and third person respectively, as are the verb forms am and is. The verb form must be selected so that it has the same person as the subject.

Number

Agreement based on grammatical number can occur between verb and subject, as in the case of grammatical person discussed above. In fact, the two categories are often conflated within verb conjugation patterns: there are specific verb forms for first person singular, second person plural and so on. Some examples:

- I really am (1st pers. singular) vs. We really are (1st pers. plural)

- The boy sings (3rd pers. singular) vs. The boys sing (3rd pers. plural)

Compound subjects are plural, and their verbs should agree. Look at the following sentence for an example:

- A pencil, a backpack, and a notebook were issued to each student.

Verbs will never agree with nouns that are in prepositional phrases. To make verbs agree with their subjects, follow this example:

- The direction of the three plays is the topic of my talk.

- The subject of “my talk” is direction, not plays, so the verb should be singular.

In the English language, verbs usually follow subjects. But when this order is reversed, the writer must make the verb agree with the subject, not with a noun that happens to precede it. For example:

- Beside the house stand sheds filled with tools.

- The subject is sheds; it is plural, so the verb must be stand.

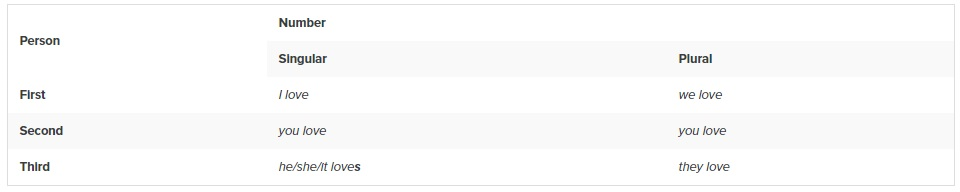

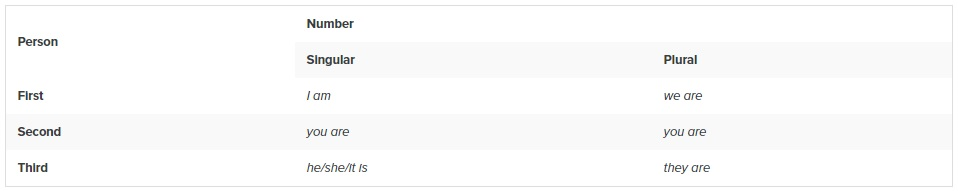

Agreement

All regular verbs (and nearly all irregular ones) in English agree in the third-person singular of the present indicative by adding a suffix of either -s or -es.

Look at the present tense of to love, for example:

The highly irregular verb to be is the only verb with more agreement than this in the present tense:

Verb Tense Consistency

One of the most common mistakes in writing is a lack of tense consistency. Writers often start a sentence in one tense but ended up in another. Look back at that sentence. Do you see the error? The first verb start is in the present tense, but ended is in the past tense. The correct version of the sentence would be “Writers often start a sentence in one tense but end up in another.”

These mistakes often occur when writers change their minds halfway through writing the sentence, or when they come back and make changes but only end up changing half the sentence. It is very important to maintain a consistent tense, not just in a sentence but across paragraphs and pages. Decide if something happened, is happening, or will happen and then stick with that choice.

Read through the following paragraphs. Can you spot the errors in tense?

Example

If you want to pick up a new outdoor activity, hiking is a great option to consider. It’s a sport that is suited for a beginner or an expert—it just depended on the difficulty hikes you choose. However, even the earliest beginners can complete difficult hikes if they pace themselves and were physically fit.

Not only is hiking an easy activity to pick up, it also will have some great payoffs. As you walked through canyons and climbed up mountains, you can see things that you wouldn’t otherwise. The views are breathtaking, and you will get a great opportunity to meditate on the world and your role in it. The summit of a mountain is unlike any other place in the world.

What errors did you spot? Let’s take another look at this passage. This time, the tense-shifted verbs have been bolded, and the phrases they belong to have been underlined:

Example

If you want to pick up a new outdoor activity, hiking is a great option to consider. It’s a sport that is suited for a beginner or an expert—it just depended on the difficulty hikes you choose. However, even the earliest beginners can complete difficult hikes if they pace themselves and were physically fit.

Not only is hiking an easy activity to pick up, it also will have some great payoffs. As you walked through canyons and climbed up mountains, you can see things that you wouldn’t otherwise. The views are breathtaking, and you will get a great opportunity to meditate on the world and your role in it. The summit of a mountain is unlike any other place in the world.

As we mentioned earlier, you want to make sure your whole passage is consistent in its tense. You may have noticed that the most of the verbs in this passage are in present tense—this is especially apparent if you ignore those verbs that have been bolded. Now that we’ve established that this passage should be in the present tense, let’s address each of the underlined segments:

- It’s a sport that is suited for a beginner or an expert—it just depended on the difficulty hikes you choose.

- depended should be the same tense as is; it just depends on the difficulty

- if they pace themselves and were physically fit.

- were should be the same tense as pace; if they pace themselves and are physically fit.

- Not only is hiking an easy activity to pick up, it also will have some great payoffs.

- will have should be the same tense as is; it also has some great payoffs

- As you walked through canyons and climbed up mountains

- walked and climbed are both past tense, but this doesn’t match the tense of the passage as a whole. They should both be changed to present tense: As you walk through canyons and climb up mountains.

- The views are breathtaking, and you will get a great opportunity to meditate on the world and your role in it.

- will get should be the same tense as are; you get a great opportunity

Here’s the corrected passage as a whole; all edited verbs have been bolded:

Example

If you want to pick up a new outdoor activity, hiking is a great option to consider. It’s a sport that can besuited for a beginner or an expert—it just depends on the difficulty hikes you choose. However, even the earliest beginners can complete difficult hikes if they pace themselves and are physically fit.

Not only is hiking an easy activity to pick up, it also has some great payoffs. As you walk through canyons and climb up mountains, you can see things that you wouldn’t otherwise. The views are breathtaking, and you get a great opportunity to meditate on the world and your role in it. The summit of a mountain is unlike any other place in the world.

Non-Finite Verbs

Just when we thought we had verbs figured out, we’re brought face-to-face with a new animal: the non-finite verbs. These words look similar to verbs we’ve already been talking about, but they act quite different than those other verbs.

By definition, a non-finite verb cannot serve as the root of an independent clause. In practical terms, this means that they don’t serve as the action of a sentence. They also don’t have a tense. While the sentence around them may be past, present, or future tense, the non-finite verbs themselves are neutral. There are three types of non-finite verbs: gerunds, participles, and infinitives.

- Gerunds all end in -ing: skiing, reading, dancing, singing, etc. Gerunds act like nouns and can serve as subjects or objects of sentences.

- A participle is used as an adjective or an adverb. There are two types of participle in English: the past and present participles.

- The present participle also takes the –ing form: (e.g., writing, singing, and raising).

- The past participle typically appears like the past tense, but some have different forms: (e.g. written, sung and raised).

- The infinitive is the basic dictionary form of a verb, usually preceded by to. Thus, to go is an infinitive.

Gerunds

Gerunds all end in -ing: skiing, reading, dancing, singing, etc. Gerunds act like nouns and can serve as subjects or objects of sentences. Let’s take a look at a few examples:

The following sentences illustrate some uses of gerunds:

- Swimming is fun.

- Here, the subject is swimming, the gerund.

- The verb is the linking verb is.

- I like swimming.

- This time, the subject of this sentence is the pronoun I.

- The verb is like.

The gerund swimming becomes the direct object.

Gerunds can be created using helping verbs as well:

- Being deceived can make someone feel angry.

- Having read the book once before makes me more prepared.

- Often the “doer” of the gerund is clearly signaled:

- We enjoyed singing yesterday (we ourselves sang)

- The cat responded by licking the cream (the cat licked the cream)

- His heart is set on being awarded the prize (he hopes that he himself will be awarded the prize)

- Tomás likes eating apricots (Tomás himself eats apricots)

However, sometimes the “doer” must be overtly specified, typically in a position immediately before the non-finite verb:

- We enjoyed their singing.

- We were delighted at Bianca being awarded the prize.

Participle

A participle is a form of a verb that is used in a sentence to modify a noun, noun phrase, verb, or verb phrase, and then plays a role similar to an adjective or adverb. It is one of the types of nonfinite verb forms.

The two types of participle in English are traditionally called the present participle (forms such as writing, singing and raising) and the past participle (forms such as written, sung and raised).

The Present Participle

Even though they look exactly the same, gerunds and present participles do different things. As we just learned, the gerund acts as a noun: e.g., “I like sleeping“; “Sleeping is not allowed.” Present participles, on the other hand, act similarly to an adjective or adverb: e.g., “The sleeping girl over there is my sister”; “Breathing heavily, she finished the race in first place.”

The present participle, or participial phrases (clauses) formed from it, are used as follows:

- as an adjective phrase modifying a noun phrase: The man sitting over there is my uncle.

- adverbially, the subject being understood to be the same as that of the main clause: Looking at the plans, I gradually came to see where the problem lay. He shot the man, killing him.

- more generally as a clause or sentence modifier: Broadly speaking, the project was successful.

The present participle can also be used with the helping verb to be to form a type of present tense: Marta was sleeping. (We’ll discuss this further in Advanced Verb Tenses.) This is something we learned a little bit about in helping verbs and tense.

The Past Participle

Past participles often look very similar to the simple past tense of a verb: finished, danced, etc. However, some verbs have different forms. Reference lists will be your best help in finding the correct past participle. Here is one such list of participles. Here’s a short list of some of the most common irregular past participles you’ll use:

Words like bought and caught are the correct past participles—not boughten or caughten.

Past participles are used in a couple of different ways:

- as an adjective phrase: The chicken eaten by the children was contaminated.

- adverbially: Seen from this perspective, the problem presents no easy solution.

- in a nominative absolute construction, with a subject: The task finished, we returned home.

The past participle can also be used with the helping verb to have to form a type of past tense (which we’ll talk about in Advanced Verb Tenses): The chicken has eaten. It is also used to form the passive voice: Tianna was voted as most likely to succeed. When the passive voice is used following a relative pronoun (like that or which) we sometimes leave out parts of the phrase:

- He had three things that were taken away from him

- He had three things taken away from him

In the second sentence, we removed the words that were. However, we still use the past participle taken. The removal of these words is called elision. Elision is used with a lot of different constructions in English; we use it shorten sentences when things are understood. However, we can only use elision in certain situations, so be careful when removing words! (We’ll discuss this further in Chapter 38: Syntax.)

Infinitives

The to-Infinitive

“To be or not to be, that is the question” (Shakespeare, Hamlet 1.3.57).The infinitive is the basic dictionary form of a verb, usually preceded by to (when it’s not, it’s called the bare infinitive, which we’ll discuss more later). Thus to go is an infinitive. There are several different uses of the infinitive. They can be used alongside verbs, as a noun phrase, as a modifier, or in a question.

With Other Verbs

The to-infinitive is used with other verbs (we’ll discuss exceptions when we talk about the bare infinitive):

- I aim to convince him of our plan’s ingenuity.

- You already know that he’ll fail to complete the task.

You can also use multiple infinitives in a single sentence: “Today, I plan to run three miles, to clean my room, and to update my budget.” All three of these infinitives follow the verb plan. Other verbs that often come before infinitives include want, convince, try, able, and like.

As a Noun Phrase

The infinitive can also be used to express an action in an abstract, general way: “To err is human”; “To know me is to love me.” No one in particular is completing these actions. In these sentences, the infinitives act as the subjects.

Infinitives can also serve as the object of a sentence. One common construction involves a dummy subject (it): “It was nice to meet you.”

As a Modifier

Infinitives can be used as an adjective (e.g., “A request to see someone” or “The man to save us”) or as an adverb (e.g., “Keen to get on,” “Nice to listen to,” or “In order to win“).

In Questions

Infinitives can be used in elliptical questions as well, as in “I don’t know where to go.”

The infinitive is also the usual dictionary form or citation form of a verb. The form listed in dictionaries is the bare infinitive, although the to-infinitive is often used in referring to verbs or in defining other verbs: “The word amble means ‘to walk slowly’”; “How do we conjugate the verb to go?”

Certain helping verbs do not have infinitives, such will, can, and may.

Split Infinitives?

One of the biggest controversies among grammarians and style writers has been the appropriateness of separating the two words of the to-infinitive as in “to boldly go.” Despite what a lot of people have declared over the years, there is absolutely nothing wrong with this construction. It is 100 percent grammatically sound.

Part of the reason so many authorities have been against this construction is likely the fact that in languages such as Latin, the infinitive is a single word, and cannot be split. However, in English the infinitive (or at least the to-infinitive) is two words, and a split infinitive is a perfectly natural construction.

The Bare Infinitive

As we mentioned previously, the infinitive can sometimes occur without the word to. The form without to is called the bare infinitive (the form with to is called the to-infinitive). In the following sentences, both sit and to sit would each be considered an infinitive:

- I want to sit on the other chair.

- I can sit here all day.

Infinitives have a variety of uses in English. Certain contexts call for the to-infinitive form, and certain contexts call for the bare infinitive; they are not normally interchangeable, except in occasional instances like after the verb help, where either can be used.

As we mentioned earlier, some verbs require the bare infinitive instead of the to-infinitive:

- The helping verb do

- Does she dance?

- Zi doesn’t sing.

- Helping verbs that express tense, possibility, or ability like will, can, could, should, would, and might

- The bears will eat you if they catch you.

- Lucas and Gerardo might go to the dance.

- You should give it a try.

- Verbs of perception, permission, or causation, such as see, watch, hear, make, let, and have (after a direct object)

- Look at Caroline go!

- You can’t make me talk.

- It’s so hard to let someone else finish my work.

The bare infinitive can be used as the object in such sentences like “What you should do is make a list.” It can also be used after the word why to ask a question: “Why reveal it?”

The bare infinitive can be tricky, because it often looks exactly like the present tense of a verb. Look at the following sentences for an example:

- You lose things so often.

- You can lose things at the drop of a hat.

In both of these sentences, we have the word lose, but in the first sentence it’s a present tense verb, while in the second it’s a bare infinitive. So how can you tell which is which? The easiest way is to try changing the subject of the sentence and seeing if the verb should change:

- She loses things so often.

- She can lose things at the drop of a hat.

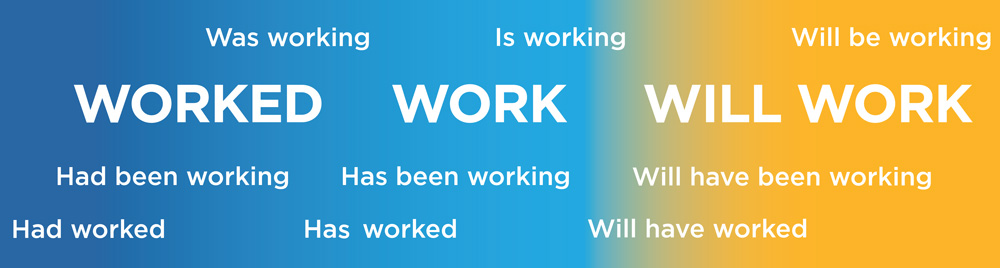

Advanced Verb Tenses

Now we’ve mastered the different pieces that we need to understand in order to discuss some more advanced tenses. These advanced tenses were mentioned briefly in Helping Verbs, and they came up again in Participles. These forms are created with different forms of to be and to have:

- He had eaten everything by the time we got there.

- She is waiting for us to get there!

- He will have broken it by next Thursday, you can be sure.

- She was singing for eight hours.

When you combine a form of to be with the present participle, you create a continuous tense; these tenses indicate a sense of continuity. The subject of the sentence was (or is, or will be) doing that thing for a while.

- Present: is working

- Past: was working

- Future: will be working (You can also say “is going to be working.”)

When you combine a form of to have with the past participle of a verb, you create a perfect tense; these tenses indicate a sense of completion. This thing had been done for a while (or has been, or will have been).

- Present: has worked

- Past: had worked

- Future: will have worked

You can also use these together. To have must always appear first, followed by the past participle been. The present participle of any verb can then follow. These perfect continuous tenses indicate that the verb started in the past, and is still continuing:

- Present: has been working

- Past: had been working

- Future: will have been working

Sometimes these verb tenses can be split by adverbs: “Zachi has been studiously reading all of the latest articles on archeology.”

4. Adjectives

Adjectives and adverbs describe things. For example, compare the phrase “the bear” to “the harmless bear” or the phrase “run” to “run slowly.”

In both of these cases, the adjective (harmless) or adverb (slowly) changes how we understand the phrase. When you first read the word bear, you probably didn’t imagine a harmless bear. When you saw the word run you probably didn’t think of it as something done slowly.

Adjectives and adverbs modify other words: they change our understanding of things.

An adjective modifies a noun; that is, it provides more detail about a noun. This can be anything from color to size to temperature to personality. Adjectives usually occur just before the nouns they modify. In the following examples, adjectives are italicized, while the nouns they modify are underlined (the big bear):

- The generator is used to convert mechanical energy into electrical energy.

- The steel pipes contain a protective sacrificial anode and are surrounded by packing material.

Adjectives can also follow a linking verb. In these instances, adjectives can modify pronouns as well. In the following examples, adjectives are italicized, while the linking verbs are underlined this time (the sun is yellow):

- The schoolhouse was red.

- I looked good today.

- She was funny.

Numbers can also be adjectives in some cases. When you say “Seven is my lucky number,” seven is a noun, but when you say “There are seven cats in this painting,” seven is an adjective because it is modifying the noun cats.

Comparable Adjectives

Some adjectives are comparable. For example, a person may be polite, but another person may be more polite, and a third person may be the most polite of the three. The word more here modifies the adjective polite to indicate a comparison is being made (a comparative), and most modifies the adjective to indicate an absolute comparison (a superlative).

Some adjectives are comparable. For example, a person may be polite, but another person may be more polite, and a third person may be the most polite of the three. The word more here modifies the adjective polite to indicate a comparison is being made (a comparative), and most modifies the adjective to indicate an absolute comparison (a superlative).

There is another way to compare adjectives in English. Many adjectives can take the suffixes –er and –est (sometimes requiring additional letters before the suffix; see forms for far below) to indicate the comparative and superlative forms, respectively:

- great, greater, greatest

- deep, deeper, deepest

- far, farther, farthest

Some adjectives are irregular in this sense:

- good, better, best

- bad, worse, worst

- little, less, least

Another way to convey comparison is by incorporating the words more and most. There is no simple rule to decide which means is correct for any given adjective, however. The general tendency is for shorter adjectives to take the suffixes, while longer adjectives do not—but sometimes sound of the word is the deciding factor.

- more beautiful not beautifuller

- more pretentious not pretentiouser

While there is no perfect rule to determine which adjectives will or won’t take –er and –est suffixes, this video lays out some “sound rules” that can serve as helpful guidelines:

TIP: The adjective fun is one of the most notable exceptions to the rules. If you follow the sound rules we just learned about, the comparative should be funner and the superlative funnest. However, for a long time, these words were considered non-standard, with more fun and most fun acting as the correct forms.

The reasoning behind this rule is now obsolete (it has a lot to do with the way fun became an adjective), but the stigma against funner and funnest remains. While the tides are beginning to change, it’s safest to stick to more fun and most fun in formal situations (such as in academic writing or in professional correspondence).

Non-Comparable Adjectives

Many adjectives do not naturally lend themselves to comparison. For example, some English speakers would argue that it does not make sense to say that one thing is “more ultimate” than another, or that something is “most ultimate,” since the word ultimate is already an absolute. Such adjectives are called non-comparable adjectives. Other examples include dead, true, and unique.

Common Mistakes with Adjectives

If you’re a native English speaker, you may have noticed that “the big red house” sounds more natural than “the red big house.” The video below explains the order in which adjectives occur in English:

5. Adverbs

Adverbs can perform a wide range of functions: they can modify verbs, adjectives, and even other adverbs. They can come either before or after the word they modify. In the following examples, adverbs are italicized while the words they modify are underlined (the quite handsome man):

Adverbs can perform a wide range of functions: they can modify verbs, adjectives, and even other adverbs. They can come either before or after the word they modify. In the following examples, adverbs are italicized while the words they modify are underlined (the quite handsome man):

- The desk is made of an especially corrosion-resistant industrial steel.

- The power company uses huge generators which are generally turned by steam turbines.

- Jaime won the race, because he ran quickly.

- This fence was installed sloppily. It needs to be redone.

An adverb may provide information about the manner, place, time, frequency, certainty, or other circumstances of the activity indicated by the verb. Some examples, where again the adverbs are italicized and the words modified are underlined:

- Suzanne sang loudly (loudly modifies the verb sang, indicating the manner of singing)

- We left it here (here modifies the verb phrase left it, indicating place)

- I worked yesterday (yesterday modifies the verb worked, indicating time)

- He undoubtedly did it (undoubtedly modifies the verb phrase did it, indicating certainty)

- You often make mistakes (often modifies the verb phrase make mistakes, indicating frequency)

They can also modify noun phrases, prepositional phrases, or whole clauses or sentences, as in the following examples. Once again, the adverbs are italicized, while the words they modify are underlined.

- I bought only the fruit (only modifies the noun phrase the fruit)

- Roberto drove us almost to the station (almost modifies the prepositional phrase to the station)

- Certainly we need to act (certainly modifies the sentence as a whole)

Intensifiers and Adverbs of Degree

Adverbs can also be used as modifiers of adjectives, and of other adverbs, often to indicate degree. Here are a few examples:

- You are quite right (the adverb quite modifies the adjective right)

- Milagros is exceptionally pretty (the adverb exceptionally modifies the adjective pretty)

- She sang very loudly (the adverb very modifies another adverb—loudly)

- Wow! You ran really quickly! (the adverb really modifies another adverb—quickly)

Other intensifiers include mildly, pretty, slightly, etc.

This video provides more discussion and examples of intensifiers:

Adverbs may also undergo comparison, taking comparative and superlative forms. This is usually done by adding more and most before the adverb (more slowly, most slowly). However, there are a few adverbs that take non-standard forms, such as well, for which better and best are used (i.e., “He did well, she did better, and I did best“).

Relative Adverbs

Relative adverbs are a subclass of adverbs that deal with space, time, and reason. In this video, David gives a quick intro to the three most common relative adverbs: when, where, and why.

As we just learned, we can use these adverbs to connect ideas about where, when, and why things happen.

Differences between Adjectives and Adverbs

As we’ve learned, adjectives and adverbs act in similar but different roles. A lot of the time, this difference can be seen in the structure of the words:

- A clever new idea.

- A cleverly developed idea.

Clever is an adjective, and cleverly is an adverb. This adjective + ly construction is a short-cut to identifying adverbs.

While –ly is helpful, it’s not a universal rule. Not all words that end in –ly are adverbs: lovely, costly, friendly, etc. Additionally, not all adverbs end in –ly: here, there, together, yesterday, aboard, very, almost, etc.

Some words can function both as an adjective and as an adverb:

- Fast is an adjective in “a fast car” (where it qualifies the noun car), but an adverb in “he drove fast” (where it modifies the verb drove).

- Likely is an adjective in “a likely outcome” (where it modifies the noun outcome), but an adverb in “we will likely go” (where it modifies the verb go).

Mistaking Adverbs and Adjectives

One common mistake with adjectives and adverbs is using one in the place of the other. For example:

- I wish I could write as neat as he can.

- The word should be neatly, an adverb, since it’s modifying a verb.

- Well, that’s real nice of you.

- Should be really, an adverb, since it’s modifying an adjective

Remember, if you’re modifying a noun or pronoun, you should use an adjective. If you’re modifying anything else, you should use an adverb.

Common Mistakes with Adverbs

Only

Have you ever noticed the effect the word only can have on a sentence, especially depending on where it’s placed? Let’s look at a simple sentence:

- She loves horses.

Let’s see how only can influence the meaning of this sentence:

- Only she loves horses.

- No one loves horses but her.

- She only loves horses.

- The one thing she does is love horses.

- She loves only horses.

- She loves horses and nothing else.

Only modifies the word that directly follows it. Whenever you use the word only make sure you’ve placed it correctly in your sentence.

Literally

A linguistic phenomenon is sweeping the nation: people are using literally as an intensifier. How many times have you heard things like “It was literally the worst thing that has ever happened to me,” or “His head literally exploded when I told him I was going to be late again”? Some people love this phrase while it makes other people want to pull their hair out.

A linguistic phenomenon is sweeping the nation: people are using literally as an intensifier. How many times have you heard things like “It was literally the worst thing that has ever happened to me,” or “His head literally exploded when I told him I was going to be late again”? Some people love this phrase while it makes other people want to pull their hair out.

So what’s the problem with this? According to Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary, the actual definition of literal is as follows:

- involving the ordinary or usual meaning of a word

- giving the meaning of each individual word

- completely true and accurate: not exaggerated

According to this definition, literally should be used only when something actually happened. Our cultural usage may be slowly shifting to allow literally as an intensifier, but it’s best to avoid using literally in any way other than its dictionary definition, especially in formal writing.

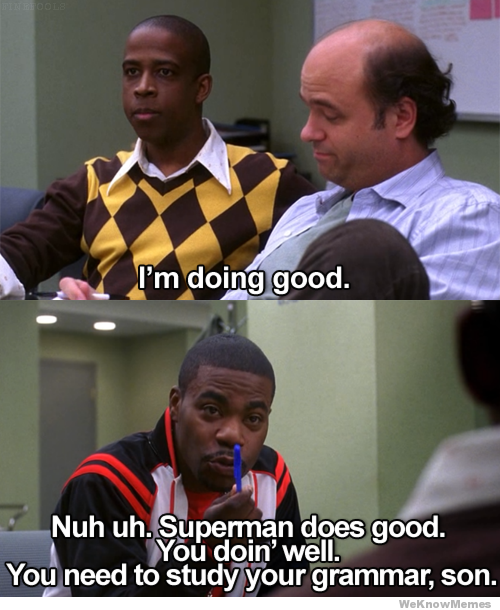

Good v. Well

Good v. Well

One of the most commonly confused adjective/adverb pairs is good versus well.

There isn’t really a good way to remember this besides memorization.

Good is an adjective.

Well is an adverb.

Let’s look at a couple of sentence where people often confuse these two:

- She plays basketball good.

- I’m doing good.

In the first sentence, good is supposed to be modifying plays, a verb; therefore the use of good—an adjective—is incorrect. Plays should be modified by an adverb. The correct sentence would read “She plays basketball well.”

In the second sentence, good is supposed to be modifying doing, a verb. Once again, this means that well—an adverb—should be used instead: “I’m doing well.”

6. Conjunctions

Conjunctions are the words that join sentences, phrases, and other words together. Conjunctions are divided into several categories, all of which follow different rules. We will discuss coordinating conjunctions, adverbial conjunctions, and correlative conjunctions. The following video, a classic from School Rock, explains the functions of conjunctions:

Coordinating Conjunctions

The most common conjunctions are and, or, and but. These are all coordinating conjunctions. Coordinating conjunctions are conjunctions that join, or coordinate, two or more equivalent items (such as words, phrases, or sentences). The mnemonic acronym FANBOYS can be used to remember the most common coordinating conjunctions: for, and, nor, but, or, yet, and so.

The most common conjunctions are and, or, and but. These are all coordinating conjunctions. Coordinating conjunctions are conjunctions that join, or coordinate, two or more equivalent items (such as words, phrases, or sentences). The mnemonic acronym FANBOYS can be used to remember the most common coordinating conjunctions: for, and, nor, but, or, yet, and so.

- For: presents a reason (“They do not gamble or smoke, for they are ascetics.”)

- And: presents non-contrasting items or ideas (“They gamble, and they smoke.”)

- Nor: presents a non-contrasting negative idea (“They do not gamble, nor do they smoke.”)

- But: presents a contrast or exception (“They gamble, but they don’t smoke.”)

- Or: presents an alternative item or idea (“Every day they gamble, or they smoke.”)

- Yet: presents a contrast or exception (“They gamble, yet they don’t smoke.”)

- So: presents a consequence (“He gambled well last night, so he smoked a cigar to celebrate.”)

Here are some examples of these used in sentences:

- Nuclear-powered artificial hearts proved to be complicated, bulky, and expensive.

- In the 1960s, artificial heart devices did not fit well and tended to obstruct the flow of venous blood into the right atrium.

- The blood vessels leading to the device tended to kink, obstructing the filling of the chambers and resulting in inadequate output.

- Any external injury or internal injury put patients at risk of uncontrolled bleeding because the small clots that formed throughout the circulatory system used up so much of the clotting factor.

- The current from the storage batteries can power lights, but the current for appliances must be modified within an inverter.

As you can see from the examples above, a comma only appears before these conjunctions sometimes. So how can you tell if you need a comma or not? There are three general rules to help you decide.

Rule 1: Joining Two Complete Ideas

Let’s look back at one of our example sentence:

- The current from the storage batteries can power lights, but the current for appliances must be modified within an inverter.

There are two complete ideas in this sentence. A complete idea has both a subject (a noun or pronoun) and a verb. The subjects have been italicized, and the verbs underlined:

- the current from the storage batteries can power lights

- the current for appliances must be modified within an inverter.

Because each of these ideas could stand alone as a sentence, the coordinating conjunction that joins them must be preceded by a comma. Otherwise, you’ll have a run-on sentence.

Run-on sentences are one of the most common errors in college-level writing. Mastering the partnership between commas and coordinating conjunctions will go a long way towards resolving many run-on sentence issues in your writing. We’ll talk more about run-ons and strategies to avoid them in Chapter 38: Syntax.

Rule 2: Joining Two Similar Items

So what if there’s only one complete idea, but two subjects or two verbs?

- Any external injury or internal injury put patients at risk of uncontrolled bleeding because the small clots that formed throughout the circulatory system used up so much of the clotting factor.

- This sentence has two subjects: external injury and internal injury. They are joined with the conjunction and; we don’t need any additional punctuation here.

- In the 1960s, artificial heart devices did not fit well and tended to obstruct the flow of venous blood into the right atrium.

- This sentence has two verbs: did not fit well and tended to obstruct. They are joined with the conjunction and; we don’t need any additional punctuation here.

Rule 3: Joining Three or More Similar Items

So what do you do if there are three or more items?

- Anna loves to run, David loves to hike, and Luz loves to dance.

- Fishing, hunting, and gathering were once the only ways for people do get food.

- Emanuel has a very careful schedule planned for tomorrow. He needs to work, study, exercise, eat, and clean.

As you can see in the examples above, there is a comma after each item, including the item just prior to the conjunction. There is a little bit of contention about this, but overall, most styles prefer to keep the additional comma (also called the serial comma). We discuss the serial comma in more depth in Chapter 39: Punctuation.

Starting A Sentence

Many students are taught—and some style guides maintain—that English sentences should not start with coordinating conjunctions.

This video shows that this idea is not actually a rule. And it provides some background for why so many people may have adopted this writing convention:

Adverbial Conjunctions

Adverbial conjunctions link two separate thoughts or sentences. When used to separate thoughts, as in the example below, a comma is required on either side of the conjunction.

Adverbial conjunctions link two separate thoughts or sentences. When used to separate thoughts, as in the example below, a comma is required on either side of the conjunction.

- The first artificial hearts were made of smooth silicone rubber, which apparently caused excessive clotting and, therefore, uncontrolled bleeding.

When used to separate sentences, as in the examples below, a semicolon is required before the conjunction and a comma after.

- The Kedeco produces 1200 watts in 17 mph winds using a 16-foot rotor; on the other hand, the Dunlite produces 2000 watts in 25 mph winds.

- For short periods, the fibers were beneficial; however, the eventual buildup of fibrin on the inner surface of the device would impair its function.

- The atria of the heart contribute a negligible amount of energy; in fact, the total power output of the heart is only about 2.5 watts.

Adverbial conjunctions include the following words. However, it is important to note that this is by no means a complete list: therefore, however, in other words, thus, then, otherwise, nevertheless, on the other hand, and in fact.

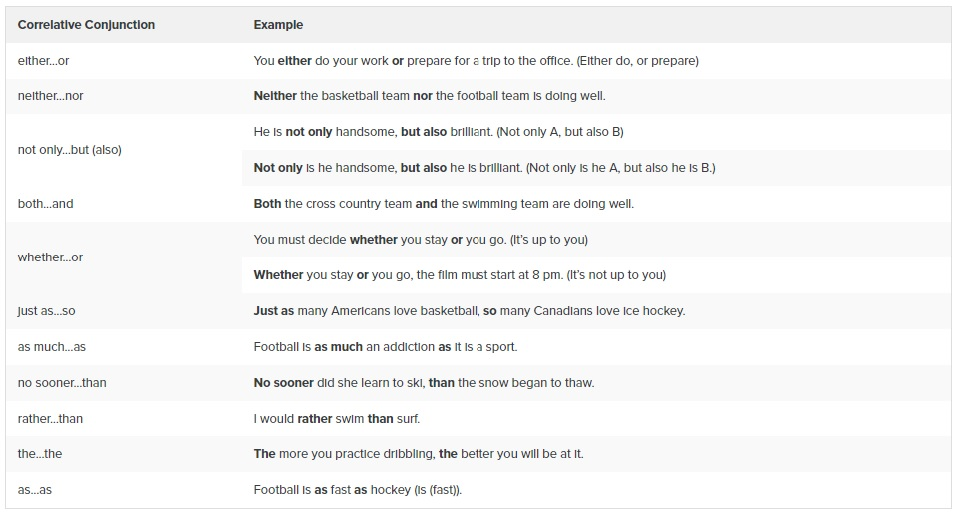

Correlative Conjunctions

Correlative conjunctions are word pairs that work together to join words and groups of words of equal weight in a sentence. This video will define this type of conjunction before it goes through five of the most common correlative conjunctions:

The table below shows some examples of correlative conjunctions being used in a sentence:

Subordinating Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunctions are conjunctions that join an independent clause and a dependent clause.

Subordinating conjunctions are conjunctions that join an independent clause and a dependent clause.

Here are some examples of subordinating conjunctions:

- The heart undergoes two cardiac cycle periods: diastole, when blood enters the ventricles, and systole, when the ventricles contract and blood is pumped out of the heart.

- Whenever an electron acquires enough energy to leave its orbit, the atom is positively charged.

- If the wire is broken, electrons will cease to flow and current is zero.

- I’ll be here as long as it takes for you to finish.

- She did the favor so that he would owe her one.

Let’s take a moment to look back at the previous examples. Can you see the pattern in comma usage? The commas aren’t dependent on the presence subordinating conjunctions—they’re dependent on the placement of clauses they’re in. Let’s revisit a couple examples and see if we can figure out the exact rules:

- The heart undergoes two cardiac cycle periods: diastole, when blood enters the ventricles, and systole, when the ventricles contract and blood is pumped out of the heart.

- These clauses are both extra information: information that is good to know, but not necessary for the meaning of the sentence. This means they need commas on either side.

- Whenever an electron acquires enough energy to leave its orbit, the atom is positively charged.

- In this sentence, the dependent clause comes before an independent clause. This means it should be followed by a comma.

- She did the favor so that he would owe her one.

- In this sentence, the independent clause comes before a dependent clause. This means no comma is required.

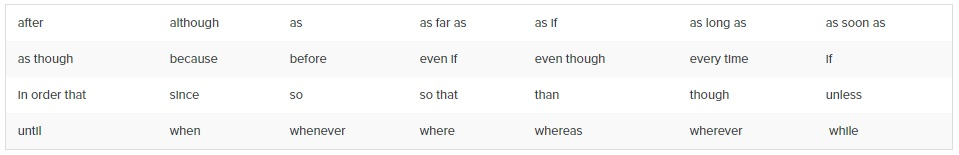

The most common subordinating conjunctions in the English language are shown in the table below:

7. Prepositions

Prepositions are relation words; they can indicate location, time, or other more abstract relationships. Prepositions are noted in italics in these examples:

Prepositions are relation words; they can indicate location, time, or other more abstract relationships. Prepositions are noted in italics in these examples:

- The woods behind my house are super creepy at night.

- She sang until three in the morning.

- He was happy for them.

TIP: The video said that prepositions are a closed group, but it never actually explained what a closed group is. Perhaps the easiest way to define a closed group is to define its opposite: an open group. An open group is a part of speech that allows new words to be added. For example, nouns are an open group; new nouns, like selfie and blog, enter the language all the time (verbs, adjectives, and adverbs are open groups as well).

Thus a closed group simply refers to a part of speech that doesn’t allow in new words. All of the word types in this section—prepositions, articles, and conjunctions—are closed groups.

A preposition combines with another word (usually a noun or pronoun) called the complement. Prepositions are still italicized, and their complements are underlined:

- The woods behind my house are super creepy at night.

- She sang until three in the morning.

- He was happy for them.