26

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Structure grammatically correct sentences in Edited American English. (SLO 1, 4, 5; GEO 1)

- Define the different parts of a sentence, such as clauses and phrases. (SLO 1, 4, 5; GEO 1)

- Correct sentence fragments and run-on sentences. (SLO 1, 4, 5; GEO 1)

- Write in active voice. (SLO 1, 4, 5; GEO 1)

- Write with parallelism. (SLO 1, 4, 5; GEO 1)

Language is made up of words, which work together to form sentences, which work together to form paragraphs. In this section, we’ll be focusing on sentences: how they’re made and how they behave. Sentences help us to organize our ideas—to identify which items belong together and which should be separated.

Language is made up of words, which work together to form sentences, which work together to form paragraphs. In this section, we’ll be focusing on sentences: how they’re made and how they behave. Sentences help us to organize our ideas—to identify which items belong together and which should be separated.

So just what is a sentence? Sentence are simply collections of words. Each sentence has a subject, an action, and punctuation. These basic building blocks work together to create endless amounts and varieties of sentences.

It’s important to have variety in your sentence length and structure. This quote from Gary Provost in 100 Ways to Improve Your Writing illustrates why:

“This sentence has five words. Here are five more words. Five-word sentences are fine. But several together become monotonous. Listen to what is happening. The writing is getting boring. The sound of it drones. It’s like a stuck record. The ear demands some variety. Now listen. I vary the sentence length, and I create music. Music. The writing sings. It has a pleasant rhythm, a lilt, a harmony. I use short sentences. And I use sentences of medium length. And sometimes when I am certain the reader is rested, I will engage him with a sentence of considerable length, a sentence that burns with energy and builds with all the impetus of a crescendo, the roll of the drums, the crash of the cymbals–sounds that say listen to this, it is important.

So write with a combination of short, medium, and long sentences. Create a sound that pleases the reader’s ear. Don’t just write words. Write music.”

You can also listen to the difference in the video below:

In order to create this variety, you need to know how sentences work and how to create them. In this section, we will identify the parts of sentences and learn how they fit together to create music in writing.

1. Basic Parts of a Sentence

Subject and Predicate

“I like the construction of sentences and the juxtaposition of words—not just how they sound or what they mean, but even what they look like.” —author Don DeLilloEvery sentence has a subject and a predicate. The subject of a sentence is the noun, pronoun, or phrase or clause the sentence is about:

- Einstein’s general theory of relativity has been subjected to many tests of validity over the years.

- Although a majority of caffeine drinkers think of it as a stimulant, heavy users of caffeine say the substance relaxes them.

- Notice that the introductory phrase, “Although a majority of caffeine drinkers think of it as a stimulant,” is not a part of the subject or the predicate.

- In a secure landfill, the soil on top and the cover block stormwater intrusion into the landfill. (compound subject)

- There are two subjects in this sentence: soil and cover.

- Surrounding the secure landfill on all sides are impermeable barrier walls. (inverted sentence pattern)

- In an inverted sentence, the predicate comes before the subject. You won’t run into this sentence structure very often as it is pretty rare.

The predicate is the rest of the sentence after the subject:

- The pressure in a pressured water reactor varies from system to system.

- In contrast, a boiling water reactor operates at constant pressure.

- The pressure is maintained at about 2250 pounds per square inch then lowered to form steam at about 600 pounds per square inch. (compound predicate)

- There are two predicates in this sentence: “is maintained at about 2250 pounds per square inch” and “lowered to form steam at about 600 pounds per square inch”

A predicate can include the verb, a direct object, and an indirect object.

Direct Object

A direct object—a noun, pronoun, phrase, or clause acting as a noun—takes the action of the main verb. A direct object can be identified by putting what?, which?, or whom? in its place.

- The housing assembly of a mechanical pencil contains the mechanical workings of the pencil.

- The action (contains) is directly happening to the object (workings).

- Lavoisier used curved glass discs fastened together at their rims, with wine filling the space between, to focus the sun’s rays to attain temperatures of 3000° F.

- The action (used) is directly happening to the object (discs).

- A 20 percent fluctuation in average global temperature could reduce biological activity, shift weather patterns, and ruin agriculture. (compound direct object)

- The actions are directly happening to multiple objects: reduce activity, shift patterns, and ruin agriculture.

- On Mariners 6 and 7, the two-axis scan platforms provided much more capability and flexibility for the scientific payload than those of Mariner 4. (compound direct object)

- The action (provided) is directly happening to multiple objects (capability and flexibility).

Indirect Object

An indirect object—a noun, pronoun, phrase, or clause acting as a noun—receives the action expressed in the sentence. It can be identified by inserting to or for.

- The company is designing senior citizens a new walkway to the park area.

- The company is not designing new models of senior citizens; they are designing a new walkway for senior citizens. Thus, senior citizens is the indirect object of this sentence.

- Walkway is the direct object of this sentence, since it is the thing being designed.

- Please send the personnel office a resume so we can further review your candidacy.

- You are not being asked to send the office somewhere; you’re being asked to send a resume to the office. Thus, the personnel office is the indirect object of this sentence.

- Resume is the direct object of this sentence, since it is the thing you should send.

Objects can belong to any verb in a sentence, even if the verbs aren’t in the main clause. For example, let’s look at the sentence:

- “When you give your teacher your assignment, be sure to include your name and your class number.”

- Your teacher is the indirect object of the verb give.

- Your assignment is the direct object of the verb give.

- Your name and your class number are the direct objects of the verb include.

Phrases and Clauses

Phrases and clauses are groups of words that act as a unit and perform a single function within a sentence. A phrase may have a partial subject or verb but not both; a dependent clause has both a subject and a verb (but is not a complete sentence). Here are a few examples:

Phrases

- Electricity has to do (with those physical phenomena) (involving electrical charges and their effects) when (in motion) and when (at rest).

- (In 1833,) Faraday’s experimentation (with electrolysis) indicated a natural unit (of electrical charge), thus (pointing (to a discrete rather than continuous charge)).

- The symbol that denotes a connection (to the grounding conductor) is three parallel horizontal lines, each of the lower ones (being shorter than the one above it).

Clauses

- Electricity manifests itself as a force of attraction, independent of gravitational and short-range nuclear attraction, when two oppositely charged bodies are brought close to one another.

- Since the frequency is the speed of sound divided by the wavelength, a shorter wavelength means a higher wavelength.

- Nuclear units planned or in construction have a total capacity of 186,998 KW, which, if current plans hold, will bring nuclear capacity to about 22% of all electrical capacity by 1995.

There are two types of clauses: dependent and independent. A dependent clause is dependent on something else; it cannot stand on its own. An independent clause, on the other hand, is free to stand by itself.

So how can you tell if a clause is dependent or independent? Let’s take a look at the clauses from the examples above:

- when two oppositely charged bodies are brought close to one another

- Since the frequency is the speed of sound divided by the wavelength

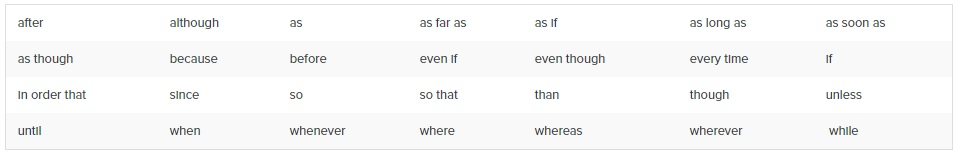

All of these clauses are dependent clauses. As we learned in Chapter 25: Parts of Speech, any clause with a subordinating conjunction is a dependent clause. For example, “I was a little girl in 1995” is an independent clause, but “Because I was a little girl in 1995” is a dependent clause. Subordinating conjunctions include the following:

Let’s look at the other clause from our examples:

- which, if current plans hold, will bring nuclear capacity to about 22% of all electrical capacity by 1995

This clause starts with the relative pronoun which (see Chapter 37: Parts of Speech for more information on these). Any clause prefaced with a relative pronoun becomes a dependent clause.

2. Basic Sentence Patterns

Subject + Verb

The simplest of sentence patterns is composed of a subject and verb without a direct object or subject complement. It uses an intransitive verb, that is, a verb requiring no direct object:

- Control rods remain inside the fuel assembly of the reactor.

- The development of wind power practically ceased until the early 1970s.

- The cross-member exposed to abnormal stress eventually broke.

- Only two types of charge exist in nature.

Subject + Verb + Direct Object

Another common sentence pattern uses the direct object:

Silicon conducts electricity in an unusual way.

The anti-reflective coating on the silicon cell reduces reflection from 32 to 22 percent.

Subject + Verb + Indirect Object + Direct Object

The sentence pattern with the indirect object and direct object is similar to the preceding pattern:

I am writing her about a number of problems that I have had with my computer.

Austin, Texas, has recently built its citizens a system of bike lanes.

3. Sentence Types

Simple Sentences

A simple sentence is one that contains a subject and a verb and no other independent or dependent clause.

- One of the tubes is attached to the manometer part of the instrument indicating the pressure of the air within the cuff.

- There are basically two types of stethoscopes.

- In this sentence, the subject and verb are inverted; that is, the verb comes before the subject. However, it is still classified as a simple sentence.

- To measure blood pressure, a sphygmomanometer and a stethoscope are needed.

- This sentence has a compound subject—that is, there are two subjects—but it is still classified as a simple sentence.

Command sentences are a subtype of simple sentences. These sentences are unique because they don’t actually have a subject:

- Clean the dishes.

- Make sure to take good notes today.

- After completing the reading, answer the following questions.

In each of these sentences, there is an implied subject: you. These sentences are instructing the reader to complete a task. Command sentences are the only sentences in English that are complete without a subject.

Compound Predicates

A predicate is everything in the verb part of the sentence after the subject (unless the sentence uses inverted word order). A compound predicate is two or more predicates joined by a coordinating conjunction. Traditionally, the conjunction in a sentence consisting of just two compound predicates is not punctuated.

- Another library media specialist has been using Accelerated Reader for ten years and has seen great results.

- This cell phone app lets users share pictures instantly with followers and categorize photos with hashtags.

Compound Sentences

A compound sentence is made up of two or more independent clauses joined by:

- a coordinating conjunction (and, or, nor, but, yet, for) and a comma

- an adverbial conjunction and a semicolon

- or just a semicolon.

For example:

- In sphygmomanometers, too narrow a cuff can result in erroneously high readings, and too wide a cuff can result in erroneously low readings.

- Some cuffs hook together; others wrap or snap into place.

Sentence Punctuation Patterns

While there are infinite possibilities for sentence construction, let’s take a look at some of the most common punctuation patterns in sentences. To do this, let’s first look at this passage about Queen Elizabeth I. You don’t need to pay attention to the words: just look at the punctuation.

The “Darnley Portrait” of Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death on March 24, 1603. Elizabeth was the daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, his second wife, who was executed two and a half years after Elizabeth’s birth. Sometimes called The Virgin Queen, the childless Elizabeth was the fifth and last monarch of the Tudor dynasty.

Elizabeth’s reign is known as the Elizabethan era. The period is famous for the flourishing of English drama, led by playwrights (such as William Shakespeare and Christopher Marlowe) and for the seafaring prowess of English adventurers (such as Francis Drake). Towards the end of her reign, a series of economic and military problems weakened her popularity. Elizabeth is acknowledged as a charismatic performer and a dogged survivor in an era when government was ramshackle and limited, and when monarchs in neighboring countries faced internal problems that jeopardized their thrones. After the short reigns of Elizabeth’s half-siblings, her 44 years on the throne provided welcome stability for the kingdom and helped forge a sense of national identity.

Now let’s look at the passage with the words removed:

____________________________________________________________________,____.

____________________________,__________,______________________________________.

_________________,___________________________________________________.

__________________________________.

________________________________________,___________(____________________________________)____________________________________(________________).

________________,_______________________________________________.

_________________________________________________________________________________,__________________________________________________________________.

________________________, __________________________________________________.

As you can see, this passage has a fairly simple punctuation structure. It simply uses periods, commas, and parentheses. These three marks are the most common punctuation you will see. Some other common sentence patterns include the following:

- ________; ________.

- Elizabeth was baptized on 10 September; Archbishop Thomas Cranmer stood as one of her godparents.

- ________; however, ________.

- The English took the defeat of the armada as a symbol of God’s favor; however, this victory was not a turning point in the war.

- ________: ____, ____, and ____.

- The period is famous for the flourishing of English drama, led by several well-known playwrights: William Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe, and Francis Beaumont.

While your sentence’s punctuation will always depend on the content of your writing, there are a few common punctuation patterns you should be aware of.

Simple sentences have these punctuation patterns:

________________________________.

________, ________________________.

Compound predicate sentences have this punctuation pattern:

________ ________ and ________.

Compound Sentences have these punctuation patterns:

________________, and ________________.

________________; ________________.

As you can see from these common patterns, periods, commas, and semicolons are the punctuation marks you will use the most in your writing. As you write, it’s best to use a variety of these patterns. If you use the same pattern repeatedly, your writing can easily become boring and drab.

4. Run-on Sentences

A run-on sentence is a sentence that goes on and on and needs to be broken up. Run-on sentences occur when two or more independent clauses are improperly joined. (We talked about clauses earlier in this chapter.) One type of run-on that you’ve probably heard of is the comma splice, in which two independent clauses are joined by a comma without a coordinating conjunction (and, or, but, etc.).

Let’s look at a few examples of run-on sentences:

- Often, choosing a topic for a paper is the hardest part it’s a lot easier after that.

- Sometimes, books do not have the most complete information, it is a good idea then to look for articles in specialized periodicals.

- She loves skiing but he doesn’t.

All three of these have two independent clauses. Each clause should be separated from another with a period, a semicolon, or a comma and a coordinating conjunction:

- Often, choosing a topic for a paper is the hardest part. It’s a lot easier after that.

- Sometimes, books do not have the most complete information; it is a good idea then to look for articles in specialized periodicals.

- She loves skiing, but he doesn’t.

TIP: Caution should be exercised when defining a run-on sentence as a sentence that just goes on and on. A run-on sentence is a sentence that goes on and on and isn’t correctly punctuated. Not every long sentence is a run-on sentence. For example, look at this quote from The Great Gatsby:

Its vanished trees, the trees that had made way for Gatsby’s house, had once pandered in whispers to the last and greatest of all human dreams; for a transitory enchanted moment man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent, compelled into an aesthetic contemplation he neither understood nor desired, face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder.

If you look at the punctuation, you’ll see that this quote is a single sentence. F. Scott Fitzgerald used commas and semicolons is such a way that, despite its great length, it’s grammatically sound, as well. Length is no guarantee of a run-on sentence.

Common Causes of Run-Ons

We often write run-on sentences because we sense that the sentences involved are closely related and dividing them with a period just doesn’t seem right. We may also write them because the parts seem to short to need any division, like in “She loves skiing but he doesn’t.” However, “She loves skiing” and “he doesn’t” are both independent clauses, so they need to be divided by a comma and a coordinating conjunction—not just a coordinating conjunction by itself.

Another common cause of run-on sentences is mistaking adverbial conjunctions for coordinating conjunctions. For example, if we were to write, “She loved skiing, however he didn’t,” we would have produced a comma splice. The correct sentence would be “She loved skiing; however, he didn’t.”

Fixing Run-On Sentences

Before you can fix a run-on sentence, you’ll need to identify the problem. When you write, carefully look at each part of every sentence. Are the parts independent clauses, or are they dependent clauses or phrases? Remember, only independent clauses can stand on their own. This also means they have to stand on their own; they can’t run together without correct punctuation.

Let’s take a look at a few run-on sentences and their revisions:

- Most of the hours I’ve earned toward my associate’s degree do not transfer, however, I do have at least some hours the University will accept.

- The opposite is true of stronger types of stainless steel they tend to be more susceptible to rust.

- Some people were highly educated professionals, others were from small villages in underdeveloped countries.

Let’s start with the first sentence. This is a comma splice sentence. The adverbial conjunction however is being treated like a coordinating conjunction. There are two easy fixes to this problem. The first is to turn the comma before however into a period. If this feels like too hard of a stop between ideas, you can change the comma into a semicolon instead.

- Most of the hours I’ve earned toward my associate’s degree do not transfer. However, I do have at least some hours the University will accept.

- Most of the hours I’ve earned toward my associate’s degree do not transfer; however, I do have at least some hours the University will accept.

The second sentence is a run-on as well. “The opposite is true of stronger types of stainless steel” and “they tend to be more susceptible to rust.” are both independent clauses. The two clauses are very closely related, and the second clarifies the information provided in the first. The best solution is to insert a colon between the two clauses:

- The opposite is true of stronger types of stainless steel: they tend to be more susceptible to rust.

What about the last example? Once again, we have two independent clauses. The two clauses provide contrasting information. Adding a conjunction could help the reader move from one kind of information to another. However, you may want that sharp contrast. Here are two revision options:

- Some people were highly educated professionals, while others were from small villages in underdeveloped countries.

- Some people were highly educated professionals. Others were from small villages in underdeveloped countries.

5. Sentence Fragments

Fragments are simply grammatically incomplete sentences—they are phrases and dependent clauses. We talked about phrases and clauses a bit in the basic parts of a sentence. These are grammatical structures that cannot stand on their own: they need to be connected to an independent clause to work in writing. So how can we tell the difference between a sentence and a sentence fragment? And how can we fix fragments when they already exist?

Common Causes of Fragments

Part of the reason we write in fragments is because we often speak that way. However, there is a difference between writing and speech, and it is important to write in full sentences. Additionally, fragments often come about in writing because a fragment may already seem too long.

Non-finite verbs (gerunds, participles, and infinitives) can often trip people up as well. Since non-finite verbs don’t act like verbs, we don’t count them as verbs when we’re deciding if we have a phrase or a clause. Let’s look at a few examples of these:

- Running away from my mother.

- To ensure your safety and security.

- Beaten down since day one.

Even though all of the above have non-finite verbs, they’re phrases, not clauses. In order for these to be clauses, they would need an additional verb that acts as a verb in the sentence.

Words like since, when, and because turn an independent clause into a dependent clause. For example “I was a little girl in 1995” is an independent clause, but “Because I was a little girl in 1995” is a dependent clause. This class of word includes the following:

Relative pronouns, like that and which, do the same type of thing as those listed above.

Coordinating conjunctions (our FANBOYS) can also cause problems. If you start a sentence with a coordinating conjunction, make sure that it is followed a complete clause, not just a phrase!

As you’re identifying fragments, keep in mind that command sentences are not fragments, despite not having a subject. Commands are the only grammatically correct sentences that lack a subject:

- Drop and give me fifty!

- Count how many times the word fragrant is used during commercial breaks.

Fixing Sentence Fragments

Let’s take a look at a couple of examples:

- Ivana appeared at the committee meeting last week. And made a convincing presentation of her ideas about the new product.

- The committee considered her ideas for a new marketing strategy quite powerful. The best ideas that they had heard in years.

- She spent a full month evaluating his computer-based instructional materials. Which she eventually sent to her supervisor with the strongest of recommendations.

Let’s look at the phrase “And made a convincing presentation of her ideas about the new product” in example one. It’s just that: a phrase. There is no subject in this phrase, so the easiest fix is to simply delete the period and combine the two statements:

- Ivana appeared at the committee meeting last week and made a convincing presentation of her ideas about the new product.

Let’s look at example two. The phrase “the best ideas they had heard in years” is simply a phrase—there is no verb contained in the phrase. By adding “they were” to the beginning of this phrase, we have turned the fragment into an independent clause, which can now stand on its own:

- The committee considered her ideas for a new marketing strategy quite powerful; they were the best ideas that they had heard in years.

What about example three? Let’s look at the clause “Which she eventually sent to her supervisor with the strongest of recommendations.” This is a dependent clause; the word which signals this fact. If we change “which she eventually” to “eventually, she,” we also turn the dependent clause into an independent clause.

- She spent a full month evaluating his computer-based instructional materials. Eventually, she sent the evaluation to her supervisor with the strongest of recommendations.

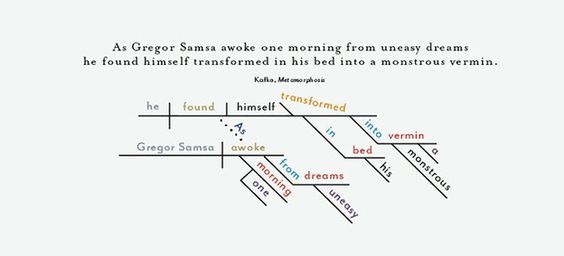

Sentence Diagram of the First Sentence from Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis

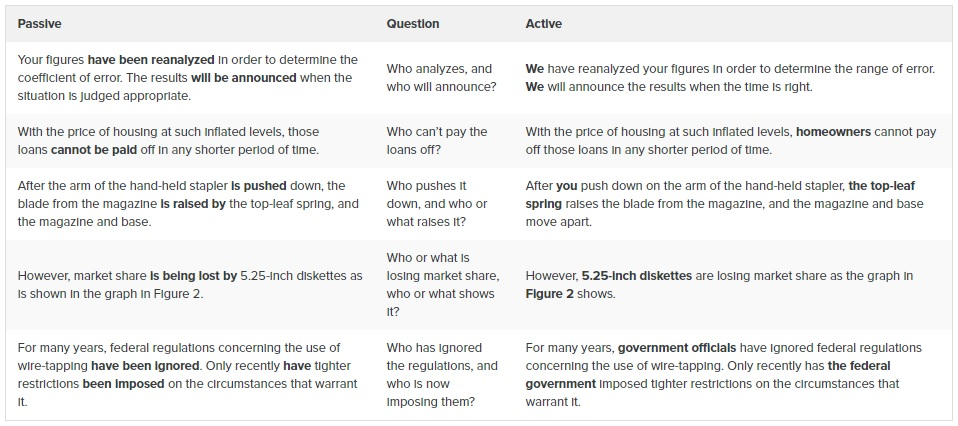

6. Active and Passive Voice

Voice is a nebulous term in writing. It can refer to the general “feel” of the writing, or it can be used in a more technical sense. In this section, we will focus on the latter sense as we discuss active and passive voice.

You’ve probably heard of the passive voice—perhaps in a comment from an English teacher or in the grammar checker of a word processor. In both of these instances, you were (likely) guided away from the passive voice. Why is this the case? Why is the passive voice so hated? After all, it’s been used twice on this page already (three times now). When the passive voice is used to frequently, it can make your writing seem flat and drab. However, there are some instances where the passive voice is a better choice than the active.

So just what is the difference between these two voices? In the simplest terms, an active voice sentence is written in the form of “A does B.” (For example, “Carmen sings the song.”) A passive voice sentence is written in the form of “B is done by A.” (For example, “The song is sung by Carmen.”) Both constructions are grammatically sound and correct.

Let’s look at a couple more examples of the passive voice:

- I’ve been hit! (or, I have been hit!)

- Jasper was thrown from the car when it was struck from behind.

You may have noticed something unique about the previous two sentences: the subject of the sentence is not the person (or thing) performing the action. The passive voice “hides” who does the action. Despite these sentences being completely grammatically sound, we don’t know who hit “me” or what struck the car.

The passive is created using the verb to be (e.g., the song is sung; it was struck from behind). Remember that to be conjugates irregularly. Its forms include am, are, is, was, were, and will be, which we learned about earlier in the course.

Remember, to be also has more complex forms like had been, is being, and was being.

- Mirella is being pulled away from everything she loves.

- Pietro had been pushed; I knew it.

- Unfortunately, my car was being towed away by the time I got to it.

Because to be has other uses than just creating the passive voice, we need to be careful when we identify passive sentences. It’s easy to mistake a sentence like “She was falling.” or “He is short.” for a passive sentence. However, in “She was falling,” was simply indicates that the sentence takes place in the past. In “He is short,” is is a linking verb. If there is no “real” action taking place, is is simply acting as a linking verb.

There are two key features that will help you identify a passive sentence:

- Something is happening (the sentence has a verb that is not a linking verb).

- The subject of the sentence is not doing that thing.

Usage

As you read at the two sentences below, think about how the different voice may affect the meaning or implications of the sentence:

- Passive voice: The rate of evaporation is controlled by the size of an opening.

- Active voice: The size of an opening controls the rate of evaporation.

The passive choice slightly emphasizes “the rate of evaporation,” while the active choice emphasizes “the size of an opening.” Simple. So why all the fuss? Because passive constructions can produce grammatically tangled sentences such as this:

- Groundwater flow is influenced by zones of fracture concentration, as can be recognized by the two model simulations (see Figures 1 and 2), by which one can see . . .

The sentence is becoming a burden for the reader, and probably for the writer too. As often happens, the passive voice here has smothered potential verbs and kicked off a runaway train of prepositions. But the reader’s task gets much easier in the revised version below:

- Two model simulations (Figures 1 and 2) illustrate how zones of fracture concentration influence groundwater flow. These simulations show . . .

To revise the above, all I did was look for the two buried things (simulations and zones) in the original version that could actually do something, and I made the sentence clearly about these two nouns by placing them in front of active verbs. This is the general principle to follow as you compose in the active voice: Place concrete nouns that can perform work in front of active verbs.

Revising Weak Passive-Voice Sentences

As we’ve mentioned, the passive voice can be a shifty operator—it can cover up its source, that is, who’s doing the acting, as this example shows:

- Passive: The papers will be graded according to the criteria stated in the syllabus. (Graded by whom, though?)

- Active: The teacher will grade the papers according to the criteria stated in the syllabus.

It’s this ability to cover the actor or agent of the sentence that makes the passive voice a favorite of people in authority—policemen, city officials, and, yes, teachers. At any rate, you can see how the passive voice can cause wordiness, indirectness, and comprehension problems.

Don’t get the idea that the passive voice is always wrong and should never be used. It is a good writing technique when we don’t want to be bothered with an obvious or too-often-repeated subject and when we need to rearrange words in a sentence for emphasis. The next page will focus more on how and why to use the passive voice.

Using the Passive Voice

There are several different situations where the passive voice is more useful than the active voice.

- When you don’t know who did the action: The paper had been moved.

- The active voice would be something like this: “Someone had moved the paper.” While this sentence is technically fine, the passive voice sentence has a more subtle element of mystery, which can be especially helpful in creating a mood in fiction.

- When you want to hide who did the action: The window had been broken.

- The sentence is either hiding who broke the window or they do not know. Again, the sentence can be reformed to say “Someone had broken the window,” but using the word someone clearly indicates that someone (though we may not know who) is at fault here. Using the passive puts the focus on the window rather than on the person who broke it, as he or she is completely left out of the sentence.

- When you want to emphasize the person or thing the action was done to: Caroline was hurt when Kent broke up with her.

- We automatically focus on the subject of the sentence. If the sentence were to say “Kent hurt Caroline when he broke up with her,” then our focus would be drawn to Kent rather than Caroline.

- A subject that can’t actually do anything: Caroline was hurt when she fell into the trees.

- While the trees hurt Caroline, they didn’t actually do anything. Thus, it makes more sense to have Caroline as the subject rather than saying “The trees hurt Caroline when she fell into them.”

Now that we know there are some instances where passive voice is the best choice, how do we use the passive voice to it fullest? The answer lies in writing direct sentences—in passive voice—that have simple subjects and verbs. Compare the two sentences below:

- Photomicrographs were taken to facilitate easy comparison of the samples.

- Easy comparison of the samples was facilitated by the taking of photomicrographs.

Both sentences are written in the passive voice, but for most ears the first sentence is more direct and understandable, and therefore preferable. Depending on the context, it does a clearer job of telling us what was done and why it was done. Especially if this sentence appears in the “Experimental” section of a report (and thus readers already know that the authors of the report took the photomicrographs), the first sentence neatly represents what the authors actually did—took photomicrographs—and why they did it—to facilitate easy comparison.

As we learned in Chapter 37: Parts of Speech, the passive voice can also be used following relative pronouns like that and which.

- I moved into the house that was built for me.

- Adrián’s dog loves the treats that are given to him.

- Brihanna has an album that was signed by the Beastie Boys.

In each of these sentences, it is grammatically sound to omit (or elide) the pronoun and to be. Elision is used with a lot of different constructions in English; we use it shorten sentences when things are understood. However, we can only use elision in certain situations, so be careful when removing words! You may find these elided sentences more natural:

- I moved into the house built for me.

- Adrián’s dog loves the treats given to him.

- Brihanna has an album signed by the Beastie Boys.

7. Parallel Structure

What exactly is parallel structure? It’s simply the practice of using the same structures or forms multiple times: making sure the parts are parallel to each other. Parallel structure can be applied to a single sentence, a paragraph, or even multiple paragraphs. Compare the two following sentences:

- Yara loves running, to swim, and biking.

- Yara loves running, swimming, and biking.

Was the second sentence easier to comprehend than the first? The second sentence uses parallelism—all three verbs are gerunds, whereas in the first sentence two are gerunds and one is an infinitive. While the first sentence is technically correct, it’s easy to trip up over the mismatching items. The application of parallelism improves writing style and readability, and it makes sentences easier to process.

Compare the following examples:

- Lacking parallelism: “She likes cooking, jogging, and to read.”

- Parallel: “She likes cooking, jogging, and reading.”

- Parallel: “She likes to cook, jog, and read.”

- Lacking parallelism: “He likes to swim and running.”

- Parallel: “He likes to swim and to run.”

- Parallel: “He likes swimming and running.”

Once again, the examples above combine gerunds and infinitives. To make them parallel, the sentences should be rewritten with just gerunds or just infinitives. Note that the first nonparallel example, while inelegantly worded, is grammatically correct: “cooking,” “jogging,” and “to read” are all grammatically valid conclusions to “She likes.”

- Lacking parallelism: “The dog ran across the yard, jumped over the fence, and down the alley sprinted.”

- Grammatical but not employing parallelism: “The dog ran across the yard and jumped over the fence, and down the alley he sprinted.”

- Parallel: “The dog ran across the yard, jumped over the fence, and sprinted down the alley.”

The nonparallel example above is not grammatically correct: “down the alley sprinted” is not a grammatically valid conclusion to “The dog.” The second example, which does not attempt to employ parallelism in its conclusion, is grammatically valid; “down the alley he sprinted” is an entirely separate clause.

Parallelism can also apply to names. If you’re writing a research paper that includes references to several different authors, you should be consistent in your references. For example, if you talk about Jane Goodall and Henry Harlow, you should say “Goodall and Harlow,” not “Jane and Harlow” or “Goodall and Henry.” This is something that would carry on through your entire paper: you should use the same mode of address for every person you mention.

You can also apply parallelism across a passage:

- Manuel painted eight paintings in the last week. Jennifer sculpted five statues in the last month. Zama wrote fifteen songs in the last two months.

Each of the sentences in the preceding paragraph has the same structure: Name + -ed verb + number of things + in the past time period. When using parallelism across multiple sentences, be sure that you’re using it well. If you aren’t careful, you can stray into being repetitive. Unfortunately, really the only way to test this is by re-reading the passage and seeing if it “feels right.” While this test doesn’t have any rules to it, it can often help.

Rhetoric and Parallelism

Parallelism can also involve repeated words or repeated phrases. These uses are part of rhetoric (a field that focuses on persuading readers) Here are a few examples of repetition:

- “The inherent vice of capitalism is the unequal sharing of blessings; the inherent virtue of socialism is the equal sharing of miseries.” —Winston Churchill

- “Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and the success of liberty.” —John F. Kennedy

- “And that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.” —Abraham Lincoln, “Gettysburg Address”

When used this way, parallelism makes your writing or speaking much stronger. These repeated phrases seem to bind the work together and make it more powerful—and more inspiring. This use of parallelism can be especially useful in writing conclusions of academic papers or in persuasive writing.

The method of human communication, either spoken or written, consisting of the use of words in a structured and conventional way.

A single distinct meaningful element of speech or writing, used with others (or sometimes alone) to form a sentence and typically shown with a space on either side when written or printed.

A set of words that is complete in itself, typically containing a subject and predicate, conveying a statement, question, exclamation, or command, and consisting of a main clause and sometimes one or more subordinate clauses.

A self-contained unit of discourse in writing dealing with a particular point or idea.

The person, group of people, place, or animal that is the focus of a profile.

Verbs that express some sort of action.

The marks, such as period, comma, and parentheses, used in writing to separate sentences and their elements and to clarify meaning.

The part of the sentence supplied after the subject.

A word used to describe an action, state, or occurrence, and forming the main part of the predicate of a sentence, such as hear, become, happen.

A noun phrase denoting a person or thing that is the recipient of the action of a transitive verb.

A noun phrase referring to someone or something that is affected by the action of a transitive verb (typically as a recipient), but is not the primary object.

A small group of words standing together as a conceptual unit, typically forming a component of a clause.

unit of grammatical organization next below the sentence in rank and in traditional grammar said to consist of a subject and predicate.

A clause that provides a sentence element with additional information, but which cannot stand as a sentence. Also called a subordinate clause.

A clause that can stand by itself as a simple sentence.

A verb that does not require a direct object or indirect object.

A sentence consisting of one independent clause.

Two or more predicates in a sentence joined by a coordinating conjunction.

A sentence comprised of two independent clauses, correctly joined.

Conjunctions that join, or coordinate, two or more equivalent items (such as words, phrases, or sentences).

A punctuation mark (,) indicating a pause between parts of a sentence. It is also used to separate items in a list and to mark the place of thousands in a large numeral.

A conjunction that links two separate thoughts or sentences.

A punctuation mark (;) indicating a pause, typically between two main clauses, that is more pronounced than that indicated by a comma.

A grammatically incorrect sentence that has two or more independent clauses improperly joined.

A type of run-on sentence that occurs when two independent clauses are improperly joined by a comma and nothing more.

A punctuation mark (:) used to precede a list of items, a quotation, or an expansion or explanation.

A grammatically incomplete sentence.

The rhetorical mixture of vocabulary, tone, point of view, and syntax that makes phrases, sentences, and paragraphs flow in a particular manner.

A type of sentence has a subject that acts upon its verb.

A grammatical construction that occurs when the object of an action becomes the subject of a sentence.

The use of successive verbal constructions in poetry or prose which correspond in grammatical structure, sound, meter, meaning, etc.

A form that is derived from a verb but that functions as a noun, in English ending in -ing.

The basic form of a verb, without an inflection binding it to a particular subject or tense.

The art of effective or persuasive speaking or writing, especially the use of figures of speech and other compositional techniques.