28

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Capitalize words correctly. (SLO 1, 4, 5; GEO 1)

- Spell words correctly. (SLO 1, 4, 5; GEO 1)

- Use specific words when necessary. (SLO 1, 4, 5; GEO 1)

- Write concisely. (SLO 1, 4, 5; GEO 1)

- Choose the appropriate language. (SLO 1, 4, 5; GEO 1)

- Use abbreviations and acronyms in writing. (SLO 1, 4, 5; GEO 1)

- Italicize words when necessary. (SLO 1, 4, 5; GEO 1)

- Understand why English grammar is difficult but essential. (SLO 1, 4, 5; GEO 1)

Rules of Diction (Word Usage)

Diction is similar to grammar: it helps determine how you should use a language and which words you should use in a specific context. However, diction focuses more on the meaning of words than on their mechanical function within the language. Diction also deals with commonly confused words, spelling, and capitalization.

Unfortunately, there aren’t a lot of hard and fast rules when it comes to word usage. Additionally, there aren’t often reasons behind the correct answers either—especially when it comes to spelling. This section will provide you with resources to help guide your decisions as you write.

1. Capitalization

Writers often refer to geographic locations, company names, temperature scales, and processes or apparatuses named after people: you must learn how to capitalize these items. There are ten fundamental rules for capitalization:

1. Capitalize the names of major portions of your paper and all references to figures and tables. Note: Some journals and publications do not follow this rule, but most do.

- Table 1

- Appendix A

- see Figure 4

2. Capitalize the names of established regions, localities, and political divisions.

- the French Republic

- Lancaster County

- the Arctic Circle

3. Capitalize the names of highways, routes, bridges, buildings, monuments, parks, ships, automobiles, hotels, forts, dams, railroads, and major coal and mineral deposits.

- the White House

- Highway 13

- Alton Railroad

4. Capitalize the proper names of persons, places and their derivatives, and geographic names (continents, countries, states, cities, oceans, rivers, mountains, lakes, harbors, and valleys).

- British

- Rocky Mountains

- Chicago

- Howard Pickering

5. Capitalize the names of historic events and documents, government units, political parties, business and fraternal organizations, clubs and societies, companies, and institutions.

- the Civil War

- Congress

- Ministry of Energy

6. Capitalize titles of rank when they are joined to a person’s name, and the names of stars and planets. Note: The names earth, sun, and moon are not normally capitalized, although they may be capitalized when used in connection with other bodies of the solar system.

- Venus

- Professor Walker

- Milky Way

7. Capitalize words named after geographic locations, the names of major historical or geological time frames, and most words derived from proper names.

- Middle Jurassic Period

- the Industrial Revolution

- Petri dish

- Coriolis force

- Planck’s constant

8. Capitalize references to temperature scales, whether written out or abbreviated.

- 10 ºF

- Celsius degrees

9. Capitalize references to major sections of a country or the world.

- the Near East

- the South

10. Capitalize the names of specific courses, the names of languages, and the names of semesters.

- Anatomy 200

- Spring semester 2016

- Russian

- Common Capitalization Errors

Just as important as knowing when to capitalize is knowing when not to. Below are a few instances where capital letters are commonly used when they should not be. Please review this advice carefully, in that we all have made such capitalization errors. When in doubt, simply consult a print dictionary.

1. Do not capitalize the names of the seasons, unless the seasons are personified, as in poetry (“Spring’s breath”):

- spring

- winter

2. Do not capitalize the words north, south, east, and west when they refer to directions, in that their meaning becomes generalized rather than site-specific.

- We traveled west.

- The sun rises in the east.

3. In general, do not capitalize commonly used words that have come to have specialized meaning, even though their origins are in words that are capitalized.

- india ink

- pasteurization

- biblical

4. Do not capitalize the names of elements. Note: This is a common capitalization error, and can often be found in published work. Confusion no doubt arises because the symbols for elements are capitalized.

- oxygen

- californium

- nitrogen

5. Do not capitalize words that are used so frequently and informally that they have come to have highly generalized meaning.

- north pole

- midwesterner

- big bang theory

- arctic climate

2. Spelling

Far too many of us use spell checkers as proofreaders, and we ultimately use them to justify our own laziness. I once received a complaint from an outraged professor that a student had continually misspelled miscellaneous as mescaline (a hallucinogenic drug). The student’s spell checker did not pick up the error, but the professor certainly did.

So proceed with caution when using spell checkers. They are not gods, and they do not substitute for meticulous proofreading and clear thinking. There is an instructive moment in a M*A*S*H episode, when Father Mulcahy complains to Colonel Potter about a typo in a new set of Bibles—one of the commandments reads “thou shalt commit adultery.” Father sheepishly worries aloud that “These lads are taught to follow orders.” For want of a single word, the intended meaning is lost. Always proofread a hard copy with your own two eyes.

Seven Rules for Spelling

Even without memorizing the rules, you can improve your spelling simply by reviewing them and scanning the examples and exceptions until the fundamental concepts begin to sink in. When in doubt, always look up the word.

1. In words ending with a silent e, you usually drop the e when you add a suffix that begins with a vowel:

- survive + al = survival

- divide + ing = dividing

- fortune + ate = fortunate

Here are a few common exceptions:

|

manageable |

singeing |

mileage |

|

advantageous |

dyeing |

acreage |

|

peaceable |

canoeing |

lineage |

2. In words ending with a silent e, you usually retain the e before a suffix than begins with a consonant.

- arrange + ment = arrangement

- forgive + ness = forgiveness

- safe + ty = safety

Here are a few common exceptions:

- ninth (from nine)

- argument (from argue)

- wisdom (from wise)

- wholly (from whole)

3. In words of two or more syllables that are accented on the final syllable and end in a single consonant preceded by a single vowel, you double the final consonant before a suffix beginning with a vowel.

- refer + ing = referring

- regret + able = regrettable

However, if the accent is not on the last syllable, the final consonant is not doubled.

- benefit + ed = benefited

- audit + ed = audited

4. In words of one syllable ending in a single consonant that is preceded by a single vowel, you double the final consonant before a suffix that begins with a vowel. (It sounds more complex than it is; just look at the examples.)

- big + est = biggest

- hot + er = hotter

- bag + age = baggage

5. In words ending in y preceded by a consonant, you usually change the y to i before any suffix that does not begin with an i.

- beauty + ful = beautiful

- accompany + ment = accompaniment

- accompany + ing = accompanying (suffix begins with i)

If the final y is preceded by a vowel, however, the rule does not apply.

- journeys

- obeying

- essays

- buys

- repaying

- attorneys

6. Use i before e except when the two letters follow c and have an e sound, or when they have an a sound as in neighbor and weigh.

|

i before e (e sound) |

e before i (a sound) |

|

shield |

vein |

|

believe |

weight |

|

grieve |

veil |

|

mischievous |

neighbor |

Here are a few common exceptions:

- weird

- either

- seize

- foreign

- ancient

- forfeit

- height

7. Some of the most troublesome words to spell are homonyms, words that sound alike but are spelled differently. Here is a partial list of the most common ones:

- accept, except

- it’s, its

- affect, effect

- already, all ready

- cite, sight, site

- forth, fourth

- know, no

- lead, led

- maybe, may be

- passed, past

- loose, lose

- than, then

- their, there, they’re

- to, too, two

- whose, who’s

- your, you’re

A few other words, not exactly homonyms, are sometimes confused:

- breath, breathe

- choose, chose

- lightning, lightening

- precede, proceed

- quiet, quite

Check the meanings of any sound-alike words you are unsure of in your dictionary.

Everyday Words that are Commonly Misspelled

If you find yourself over-relying on spell checkers or misspelling the same word for the seventeenth time this year, it would be to your advantage to improve your spelling. One shortcut to doing this is to consult this list of words that are frequently used and misspelled.

Many smart writers even put a mark next to a word whenever they have to look it up, thereby helping themselves identify those fiendish words that give them the most trouble. To improve your spelling, you must commit the words you frequently misspell to memory, and physically looking them up until you do so is an effective path to spelling perfection.

3. Commonly Misused Terms and Phrases

“When I woke up this morning my girlfriend asked me, ‘Did you sleep good?’ I said, ‘No, I made a few mistakes.’” —Steven WrightEveryone struggles at one time or another with finding the right word to use. We’ve all sent out that email only to realize we typed there when we should have said their. How many times have you found yourself puzzling over the distinction between affect and effect or lay and lie? You can also find billboards, road signs, ads, and newspapers with usage errors such as these boldly printed for all to see:

- “Man Alright After Crocodile Attack” (Alright should be All Right)

- “This Line Ten Items or Less” (Less should be Fewer)

- “Auction at This Sight: One Week” (Sight should be Site)

- “Violent Storm Effects Thousands” (Effects should be Affects)

Perhaps there is little need here to preach about the value of understanding how to correctly use words. Quite simply, in formal writing, conventions have been established to aid us in choosing the best term for the circumstances, and you must make it your business to learn the rules regarding the trickiest and most misused terms.

This PDF contains a list of several commonly confused words—as well as how to tell which word you should use. For a searchable and comprehensive list of commonly misused words and phrases and some practice quizzes, visit the Common errors in English usage page from Washington State University.

Rules of Style

Style is a choice you make as a writer in response to the rhetorical situation. You learned several strategies for using style in ways that are appropriate for your purpose, readers, and genre. Here, you will learn strategies for writing with clarity and conciseness. You will also learn strategies for recognizing when certain kinds of language are and are not appropriate.

1. Conciseness

Concise writing shows that you are considerate of your readers. You do not need to eliminate details and other content to achieve conciseness; rather, you cut empty words, repetition, and unnecessary details.

Follow these guidelines to achieve conciseness in your writing:

1. Avoid redundancy. Redundant words and expressions needlessly repeat what has already been said. Delete them when they appear in your writing.

2. Avoid wordy expressions. Phrases such as In the final analysis and In the present day and age add no important information to sentences and should be removed and/or replaced.

3. Avoid unnecessary intensifiers. Intensifiers such as really, very, clearly, quite, and of course usually fail to add meaning to the words they modify. Delete them when doing so does not change the meaning of the sentence, or when you could replace the words with a single word (for instance, replacing very good with excellent).

4. Avoid excess use of prepositional phrases. The use of too many prepositional phrases within a sentence makes for wordy writing. Always use constructions that require the fewest words.

5. Avoid negating constructions. Negating constructions using words such as no and not often add unneeded words to sentences. Use shorter alternatives when they are available.

6. Use the passive voice only when necessary. When there is no good reason to use the passive voice, choose the active voice.

Here are more examples of wordy sentences that violate these guidelines, with unnecessary words in italics:

- If the two groups cooperate together, there will be positive benefits for both. [Uses redundancy]

- There are some people who think the metric system is un-American. [Uses wordy expression]

- The climb up the mountain was very hard on my legs and really taxed my lungs and heart. [Uses unnecessary modifiers]

- On the day of his birth, we walked to the park down the block from the house of his mother. [Uses too many prepositional phrases]

- She did not like hospitals. [Uses negating construction when a shorter alternative is available]

- The door was closed by that man over there. [Uses passive voice when active voice is preferable]

Corrections to the wordy sentences above result in concise sentences:

- If the two groups cooperate, both will benefit. [This correction also replaces the wordy construction there will be . . . for both with a shorter, more forceful alternative.]

- Some people think the metric system is un-American.

- The climb up the mountain was hard on my legs and taxed my lungs and heart.

- On his birthday, we walked to the park near his mother’s house.

- She hated hospitals.

- That man over there closed the door.

2. Appropriate Language

Effective writers communicate using appropriate language.

Suitability

Some situations require formal language. Formal language communicates clearly and directly with a minimum of stylistic flourish. Its tone is serious, objective, and often detached. Formal language avoids slang, pretentious words, and unnecessary technical jargon. Informal language, on the other hand, is particular to the writer’s personality or social group and assumes a closer and more familiar relationship between the writer and the reader. Its tone is casual, subjective, and intimate. Informal language can also employ slang and other words that would be inappropriate in formal writing.

As informal language is rarely used within most academic, technical, or business settings, the following examples show errors in the use of formal language:

- The director told the board members to push off. [Uses informal language]

- Professor Oyo dissed Marta when she arrived late to his class for the third time in a row. [Uses slang]

- The aromatic essence of the gardenia was intoxicating. [Uses pretentious words]

- The doctor told him to take salicylate to ease the symptoms of viral rhinorrhea. [Uses unnecessary jargon]

Employing formal language correctly, these examples could be revised as follows:

- The director told the board members to leave.

- Professor Oyo spoke disrespectfully to Marta when she arrived late to his class for the third time in a row.

- The scent of the gardenia was intoxicating.

- The doctor told him to take aspirin to ease his cold symptoms.

Sexist Usage

Gender-exclusive terms such as policeman and chairman are offensive to many readers today. Writers who are sensitive to their audience, therefore, avoid such terms, replacing them with expressions such as police officer and chairperson or chair. Most sexist usage in language involves masculine nouns, masculine pronouns, and patronizing terms.

Masculine Nouns

Do not use man and its compounds generically. For many people, these words are specific to men and do not account for women as separate and equal people. Here are some examples of masculine nouns and appropriate gender-neutral substitutions:

| Masculine Noun | Gender-Neutral Substitution |

| mailman | mail carrier |

| businessman | businessperson, executive, manager |

| fireman | firefighter |

| man-hours | work hours |

| mankind | humanity, people |

| manmade | manufactured, synthetic |

| salesman | salesperson, sales representative |

| congressman | member of Congress, representative, senator |

Making gender-neutral substitutions often entails using a more specific word for a generalized term, which adds more precision to writing.

Masculine Pronouns

Avoid using the masculine pronouns he, him, and his in a generic sense, meaning both male and female. Consider the following options:

1. Eliminate the pronoun. Every writer has an individual style. [Instead of “Every writer has his own style.”]

2. Use plural forms. Writers have their own styles. [Instead of “A writer has his own style.”]

3. Use he or she, one, or you as alternates only sparingly. Each writer has his or her own style. [Instead of “Each writer has his own style.”] One has an individual writing style. [Instead of “He has his own individual writing style.”] You have your own writing style. [Instead of “A writer has his own style.”]

Patronizing Terms

Avoid terms that cast men or women in gender-exclusive roles or imply that women are subordinate to men. Here are some examples of biased or stereotypical terms and their gender-neutral substitutions:

| Biased/Stereotypical Term | Gender-Neutral Substitution |

| career girl | professional |

| cleaning lady | housecleaner |

| coed | student |

| housewife | homemaker |

| lady lawyer | lawyer |

| male nurse | nurse |

| stewardess | flight attendant |

Biases and Stereotypes

Most writers are sensitive to racial and ethnic biases or stereotypes, but they should also avoid language that shows insensitivity to age, class, religion, and sexual orientation. According to a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, using inclusive language can reduce mental biases. Researchers reported that participants who were assigned to use gender-neutral terms for certain tasks were more likely to use non-male names for other tasks, had increased positive feelings toward LGBT people, decreased their mental biases that favored men, and had a greater awareness of other genders.

3. Abbreviations and Acronyms

Abbreviations (the shortened form of a word or phrase) and acronyms (words formed from the initial letters of a phrase) are commonly used in technical writing. In some fields, including chemistry, medicine, computer science, and geographic information systems, acronyms are used so frequently that the reader can feel lost in an alphabet soup. However, the proper use of these devices enhances the reading process, fostering fluid readability and efficient comprehension.

Some style manuals devote entire chapters to the subject of abbreviations and acronyms, and your college library no doubt contains volumes that you can consult when needed. Here, we provide a few principles you can apply to use abbreviations and acronyms in your writing.

Abbreviations

- Typically, we abbreviate social titles (like Ms. and Mr.) and professional titles (like Dr., Rev.).

- Titles of degrees should be abbreviated when following someone’s name. However, in resumes and cover letters, you should avoid abbreviations

- Gloria Morales-Myers, PhD

- I received a Bachelor of Arts in 2014.

- Most abbreviations should be followed with a period (Mar. for March), except those representing units of measure (mm for millimeter).

- Typically, do not abbreviate geographic names and countries in text (i.e., write Saint Cloud rather than St. Cloud). However, these names are usually abbreviated when presented in “tight text” where space can be at a premium, as in tables and figures.

- Use the ampersand symbol (&) in company names if the companies themselves do so in their literature, but avoid using the symbol as a narrative substitute for the word and in your text.

- In text, spell out addresses (Third Avenue; the Chrysler Building) but abbreviate city addresses that are part of street names (Central Street SW).

- Try to avoid opening a sentence with an abbreviation; instead, write the word out.

- Latin abbreviations: write out except in source citations and parenthetical comments.

- etc. : and so forth (et cetera—applies to things)

- i.e. : that is (id est)

- e.g. : for example (exempli gratia)

- cf. : compare (confer)

- et al. : and others (et alii—applies to people)

- N.B. : note well (nota bene)

Acronyms

With few exceptions, present acronyms in full capital letters (FORTRAN; NIOSH). Some acronyms, such as scuba and radar, are so commonly used that they are not capitalized.

- Unless they appear at the end of a sentence, do not follow acronyms with a period.

- NOAA is a really great organization.

- I want to work for the USGS.

- Acronyms can be pluralized with the addition of a lowercase s

- Please choose between these three URLs.

- Acronyms can be made possessive with an apostrophe followed by a lowercase s:

- The DOD’s mandate will be published today.

- As subjects, acronyms should be treated as singulars, even when they stand for plurals; therefore, they require a singular verb

- NASA is committed to . . .

- Always write out the first in-text reference to an acronym, followed by the acronym itself written in capital letters and enclosed by parentheses. Subsequent references to the acronym can be made just by the capital letters alone. For example:

- Geographic Information Systems (GIS) is a rapidly expanding field. GIS technology . . .

- Use acronyms for organizations: NASA, NBC, CIA.

- The acronym US can be used as an adjective (US citizen), but United States should be used when you are using it as a noun.

Abbreviations are to be avoided in most prose:

Examples

Different abbreviations and acronyms are treated differently. You can review this PDF to check the proper treatment of some commonly used abbreviations and acronyms. For a much more detailed listing of abbreviations and acronyms, you can check in the back pages of many dictionaries, or consult the free online version of the United States Government Printing Office Style Manual.

4. Numbers

The rules for expressing numbers are relatively simple and straightforward. You spell out numbers ten and below. The numbers above this (10-999,999) should be written with Arabic numerals. Starting at 1 million, write the Arabic numeral followed by the written word (million, billion, trillion, etc.).

The rules for expressing numbers are relatively simple and straightforward. You spell out numbers ten and below. The numbers above this (10-999,999) should be written with Arabic numerals. Starting at 1 million, write the Arabic numeral followed by the written word (million, billion, trillion, etc.).

- There were 60 dogs in the competition.

- I don’t think it’s possible to get 264 bracelets made in one week.

- This study is based on three different ideas

- In this treatment, the steel was heated 1.8 million different times.

If a sentence begins with a number, the number should be written out:

- Fourteen of the participants could not tell the difference between samples A and B.

- Eighteen hundred and eighty-eight was a very difficult year.

- You may want to revise sentences like this, so the number does not come first: “The year 1888 was quite difficult.”

You should treat similar numbers in grammatically connected groups alike:

- Two dramatic changes followed: four samples exploded and thirteen lab technicians resigned.

- Sixteen people got 15 points on the test, thirty people got 10 points, and three people got 5 points.

- In this sentence, there are two different “categories” of numbers: those that modify the noun people and those that modify the noun points. You can see that one category is spelled out (people) and the other is in numerals (points). This division helps the reader immediately spot which category the numbers belong to.

When you write a percentage, the number should always be written numerically (even if its ten or under). If you’re writing in a non-technical field, you should spell out the word percent. These same rules apply to degrees of temperature:

- The judges have to give prizes to at least 25 percent of competitors.

- The sample was heated to 80 degrees Celsius.

All important measured quantities—particularly those involving decimal points, dimensions, degrees, distances, weights, measures, and sums of money—should be expressed in numeral form:

- The metal should then be submerged for precisely 1.3 seconds.

- On average, the procedure costs $25,000.

- The depth to the water at the time of testing was 16.16 feet.

Check out these handy resources related to expressing numbers and numerals in text:

Technical Writing Best Practices – By the Numbers

“Using Numbers, Writing Lists” advice from Capital Community College website

5. Italics

Italic type, which slants to the right, has specialized uses.

1. Titles of works published independently (known as “containers” in MLA Style):

- The Atlantic Monthly (magazine)

- A Farewell to Arms (book)

- Leaves of Grass (book-length poems)

- The Wall Street Journal (newspaper)

- American Idol (television program)

- The Glass Menagerie (play)

2. Ships, aircraft, spacecraft, and trains

- Challenger (spacecraft)

- Leasat 3 (communications satellite)

- San Francisco Zephyr (train)

3. Italics are also used for words, letters, and numbers used as themselves in a sentence:

- The process of heat transfer is called conduction.

- The letter e is the most commonly used vowel.

- Many people consider 13 to be an unlucky number.

4. Italics can also be used for emphasis:

- “I said, ‘Did you buy the tickets?’ not ‘Would you buy the tickets?’”

Although underlining was used as a substitute for italics in the past, writers generally avoid it nowadays because underlining is used for other purposes (for example, to indicate a hyperlink in Web and other electronic writing).

Why Is Grammar Important?

Take a moment and try to imagine a world without language: written, signed, or spoken. It’s pretty hard to conceptualize, right? Language is a constant presence all around us. It’s how we communicate with others; without language, it would be incredibly difficult to connect people.

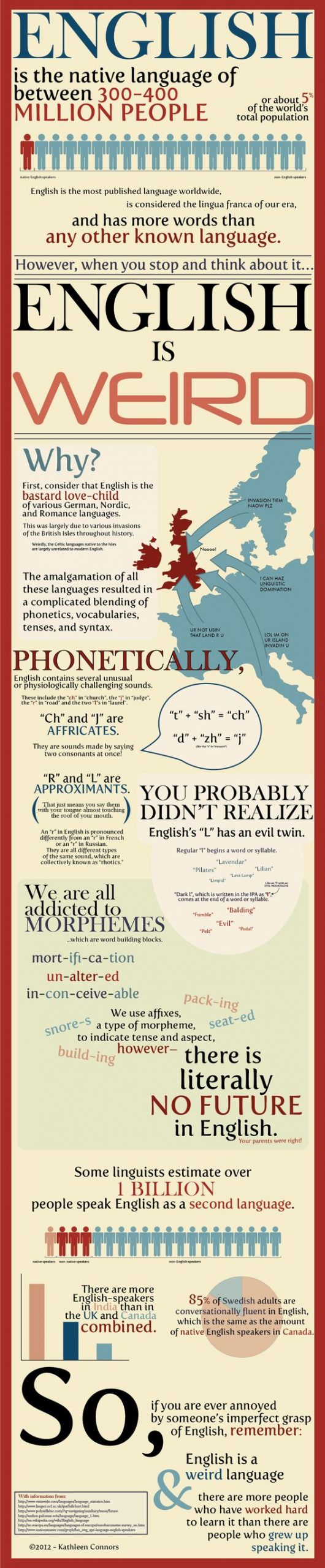

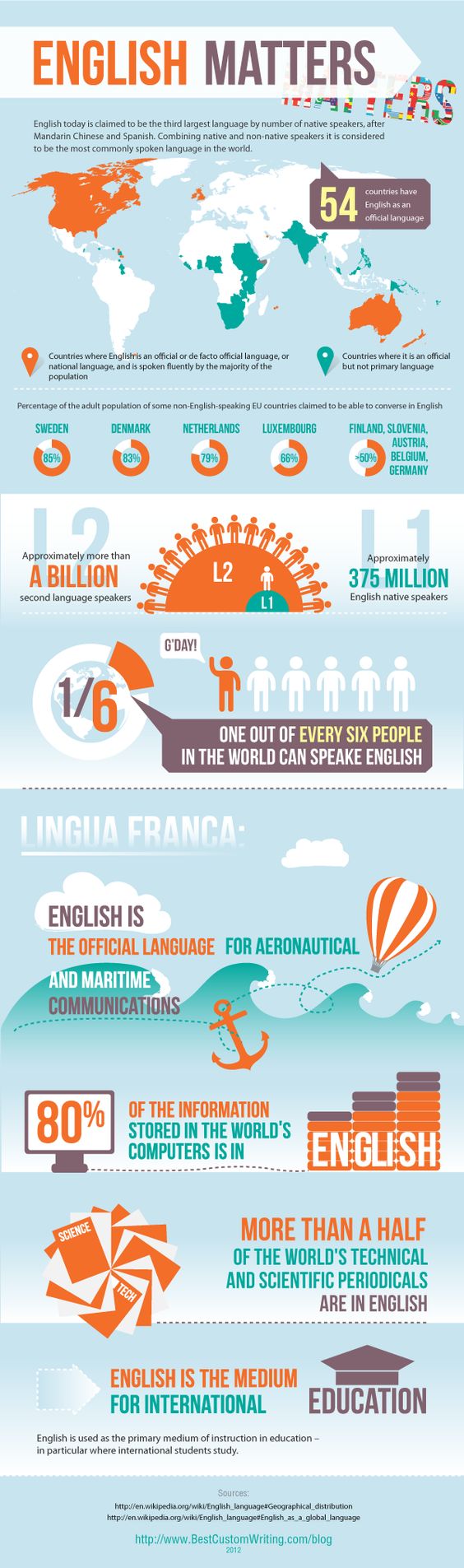

Many people are self-conscious of their speech and worry that the way they talk is incorrect: this simply isn’t true. There are several different types of English—all of which are equally dynamic and complex. However, each variety is appropriate in different situations. When you’re talking to your friends, you should use slang and cultural references—if you speak in formal language, you can easily come off as uptight or rude. If you’re sending a quick casual message—via social media or texting—you don’t need to worry too much about capitalization or strict punctuation. Feel free to have five exclamation points standing alone, if that gets your point across.

However, there’s this thing called Standard American English. This type of English exists for the sake of communication across cultural lines, where standardized rules and conventions are necessary. How many times have you heard people of older generations ask just what smh or rn mean? This is where grammar comes in. Grammar is a set of rules and conventions that dictate how Standard American English works. These rules are simply tools that speakers of a language can use. When you learn how to use the language, you can craft your message to communicate exactly what you want to convey.

Additionally, when you speak or write with poor grammar, others will often make judgments about who you are as a person. As authors Joseph Williams and Gregory G. Colomb wrote, “Follow all the rules all the time because sometime, someone will criticize you for something.”

Code switching is the ability to use two different varieties (or dialects) of the same language. Most people do this instinctively. If you were writing a paper, you might say something like “The experiment requires not one but four different procedures” in order to emphasize number. In an informal online setting, on the other hand, you might say something like “I saw two (2) buses drive past.” The most important facet of code switching is knowing when to use which variety.

In formal academic writing, standardized English is the correct variety to use.

As you go through this section, remember that these are the rules for just one type of English.

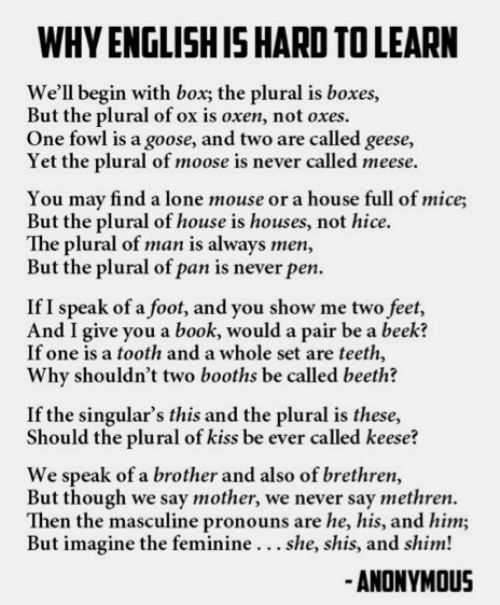

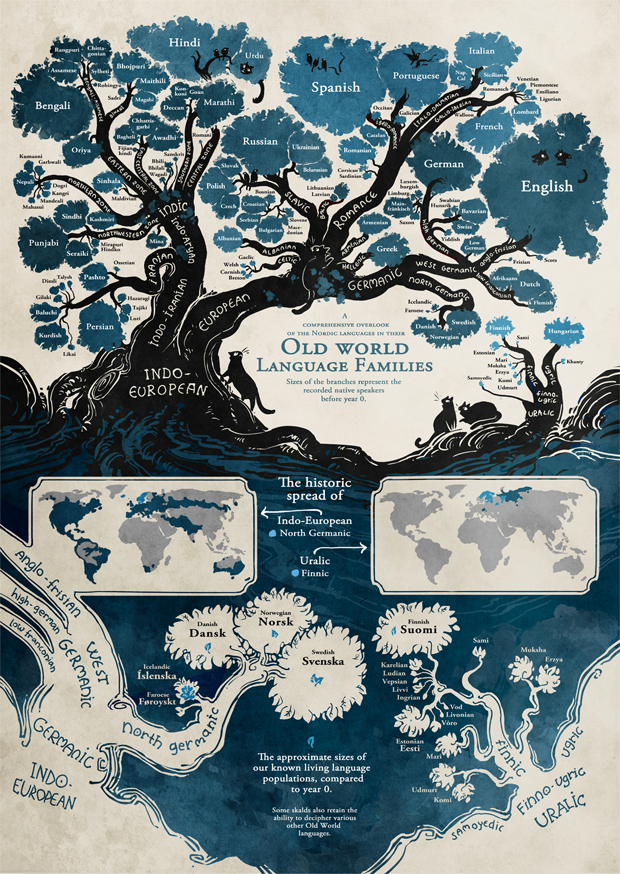

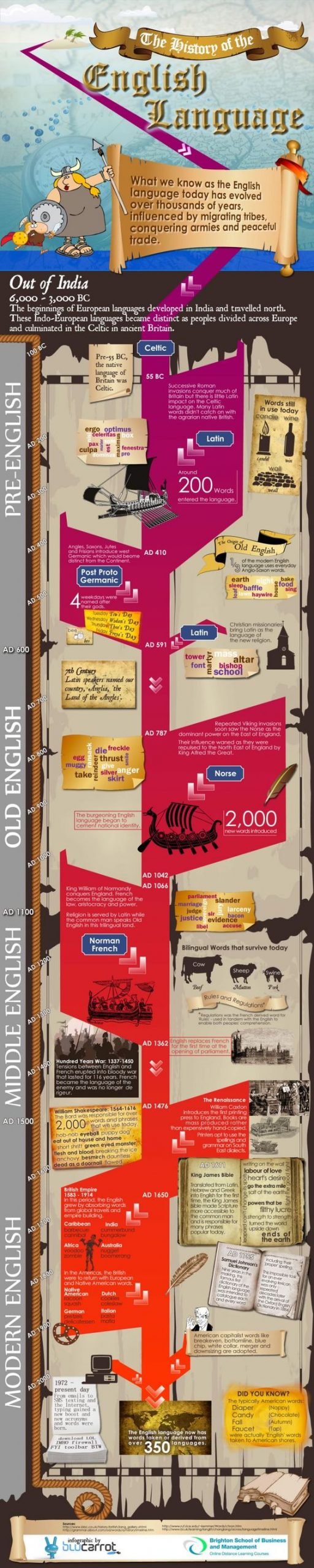

Why Is Grammar So Difficult to Learn?: A Brief History of the English Language

Why Do I Need to Learn Grammar?

People have been learning grammar for almost as long as language has existed. In ancient Greece and Rome, students learned grammar as part of their studies in rhetoric. In medieval times, grammar was considered one of the seven liberal arts. Although the methods for learning grammar have changed drastically over time, the reasons for doing so have not.

Grammar is important because it is the language that makes it possible for us to talk about language. Grammar names the types of words and word groups that make up sentences not only in English but in any language. As human beings, we can put sentences together even as children — we can all do grammar. But to be able to talk about how sentences are built, about the types of words and word groups that make up sentences — that is knowing about grammar. And knowing about grammar offers a window into the human mind and into our amazingly complex mental capacity.

People associate grammar with errors and correctness. But knowing about grammar also helps us understand what makes sentences and paragraphs clear and interesting and precise. Grammar can be part of literature discussions, when we and our students closely read the sentences in poetry and stories. And knowing about grammar means finding out that all languages and all dialects follow grammatical patterns.

Teaching grammar will not make writing errors go away. Students make errors in the process of learning, and as they learn about writing, they often make new errors, not necessarily fewer ones. But knowing basic grammatical terminology does provide students with a tool for thinking about and discussing sentences. And lots of discussion of language, along with lots of reading and lots of writing, are the three ingredients for helping students write in accordance with the conventions of standard English.

Grammar Resources

- Hoonuit (available on Blackboard): Grammar 101 and Word Study video series

- Your Dictionary

- Guide to Grammar and Writing from the Capital Community College Fund

- Interactive Grammar Practice from the Capital Community College Fund

- Grammarly

- Glossary of Correct Usage from English Daily

- How to Edit an English Essay from Paradigm

Word choice; a writer's or speaker's distinctive vocabulary choices and style of expression.

The whole system and structure of a language or of languages in general, usually taken as consisting of syntax and morphology (including inflections) and sometimes also phonology and semantics.

The method of human communication, either spoken or written, consisting of the use of words in a structured and conventional way.

A single distinct meaningful element of speech or writing, used with others (or sometimes alone) to form a sentence and typically shown with a space on either side when written or printed.

The circumstances that form the setting for an event, statement, or idea, and in terms of which it can be fully understood and assessed.

The process or activity of writing or naming the letters of a word.

The action of writing or printing in capital letters or with an initial capital.

Each of two or more words having the same spelling or pronunciation but different meanings and origins.

The manner of expressing thought in language characteristic of an individual, period, school, or nation.

Any set of circumstances that involves at least one person (the author) communicating a message to at least one other person (the audience).

The quality of being short and clear, and expressing what needs to be said without unnecessary words.

The act of using a word, phrase, etc., that repeats something else and is therefore unnecessary.

Adverbs that communicate the degree of intensity of their antecedent.

A modifying phrase consisting of a preposition and its object.

The action or logical operation of negating or making negative.

A grammatical construction that occurs when the object of an action becomes the subject of a sentence.

A type of sentence has a subject that acts upon its verb.

Having a relaxed, friendly, or unofficial style, manner, or nature.

Of or denoting a style of writing or public speaking characterized by more elaborate grammatical structures and more conservative and technical vocabulary.

The shortened form of a word or phrase.

Words formed from the initial letters of a phrase.

A font based on a stylised form of calligraphic handwriting that normally slants slightly to the right. Italics are generally used for titles.

The ability to use two different varieties (or dialects) of the same language

A particular form of a language which is peculiar to a specific region or social group.