1

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Use prewriting techniques to get your ideas flowing. (GEO 1, 2; SLO 1)

- Develop your ideas with heuristics. (GEO 1, 2; SLO 1)

- Reflect on your ideas with exploratory writing and extend them in new directions. (GEO 1, 2; SLO 1)

- Identify and conquer writer’s block (GEO 1, 2; SLO 1)

Coming up with new ideas is often the hardest part about writing. You stare at the page or screen, and it stares back. Writers can choose from a wide variety of techniques to help them “invent” their ideas and think about their topics from new perspectives. In this chapter, you will learn about three types of invention strategies that you can use to generate new ideas and explore your topic: Prewriting uses visual and verbal strategies to put your ideas on the screen or a piece of paper, so you can consider them and figure out how you want to approach your topic. Heuristics use time-tested techniques that help you ask good questions about your topic and figure out what kinds of information you will need to support your claims and statements. Exploratory writing uses reflective strategies to help you better understand how you feel about your topic. This kind of open-ended writing helps you turn those thoughts into sentences, paragraphs, and outlines. Some of these invention strategies will work better for you than others. You will also discover that some of them are better than others for particular kinds of papers. Try them all to see which ones are most helpful as you tap into your creativity.

Prewriting

Prewriting helps you put your ideas on the screen or a piece of paper, often in a visual way. Your goal while prewriting is to figure out what you already know about your topic and to start coming up with new ideas that go beyond your current understanding.

Concept Mapping

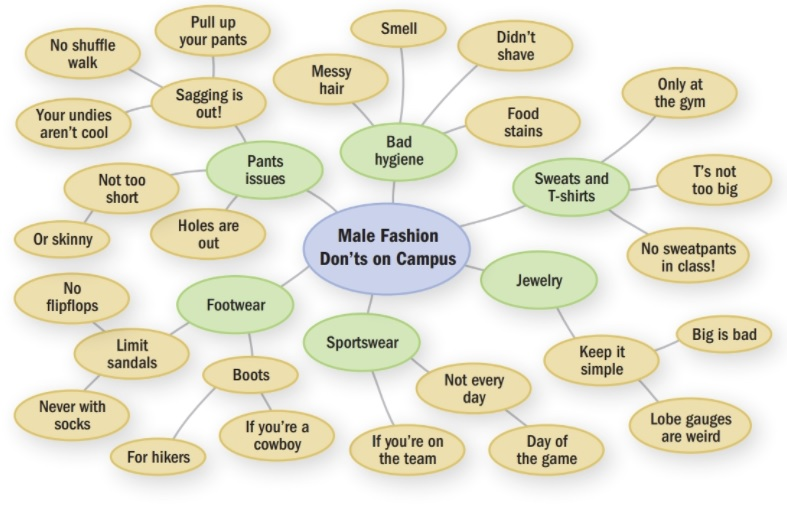

One of the most common prewriting tools is concept mapping. To create a concept map, write your topic in the middle of your screen or a piece of paper (Fig. 1.1). Put a circle around it. Then write down as many other ideas as you can about your topic. Circle those ideas and draw lines that connect them with each other.

The magic of concept mapping is that it allows you to start throwing your ideas onto the screen or a blank page without worrying about whether they make sense at the moment. Each new idea in your map will help you come up with other new ideas. Just keep going. Then, when you run out of new ideas, you can work on connecting ideas into larger clusters. For example, Figure 16.1 shows a concept map about the pitfalls of male fashion on a college campus. A student made this concept map for an argument paper. She started out by writing “Male Fashion Don’ts on Campus” in the middle of a sheet of paper. Then she began jotting down anything that came to mind. Eventually, the whole sheet was filled out. She then linked ideas into larger clusters.

With her ideas in front of her, she could then choose the topic and angle that best suited her audience and purpose. The larger clusters became major topics in her argument (e.g., sweats and T-shirts, jewelry, footwear, hygiene, saggy pants, and sports uniforms). Or she could have chosen just one of those clusters (e.g., footwear) and structured her entire argument around that narrower topic. If you like concept mapping, you might try one of the free mapping software packages available online, including Coggle, NovaMind, MindNode, MindMeister, and MindManager, among others.

Freewriting

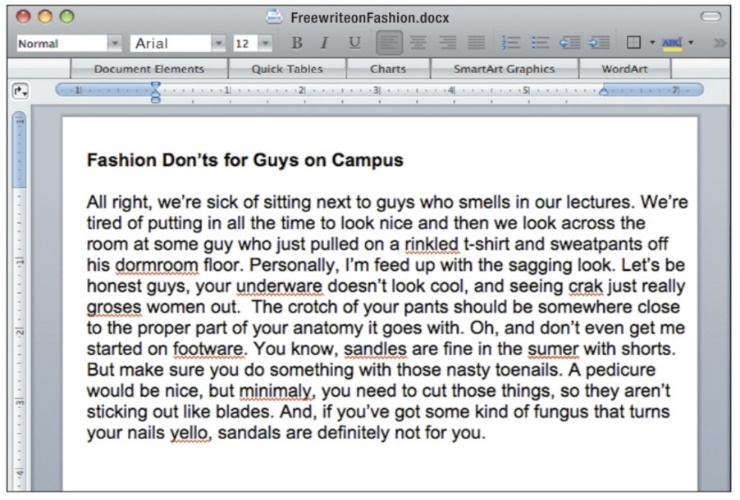

When freewriting, all you need to do is open a page on your computer or pull out a piece of paper. Then write as much as you can for five to ten minutes, typing or jotting down anything that comes into your mind. Don’t stop writing, and don’t worry about putting your ideas into real sentences or paragraphs. If you find yourself running out of words, try finishing phrases like “What I mean is . . .” or “Here’s my point. . . .” When using a computer, try darkening the screen or closing your eyes as you free-write. That way, the words you have already written won’t distract you from writing down new ideas. Plus, a dark screen will help you avoid the temptation to go back and fix any typos and garbled sentences. Fig. 1.2 shows an example freewrite. The text has typos and some of the sentences make no sense. That’s fine. The author is just getting her ideas on the screen.

When you are finished freewriting, go through your text, highlighting or underlining your best ideas. Some people find it helpful to do a second, follow-up freewrite that focuses just on the best ideas.

Brainstorming

To brainstorm about your topic, open a new page on your screen or pull out a piece of paper. Then list everything that comes to mind about your topic. As in freewriting, just keep listing ideas for about five to ten minutes without stopping. Next, choose your best idea and create a second brainstorming list on a separate sheet of paper. Again, list everything that comes to mind about this best idea. Making two lists will help you narrow your topic and deepen your thoughts about it.

Storyboarding

Movie scriptwriters and advertising designers use a technique called storyboarding to help them sketch out their ideas. Storyboarding involves drawing a set of pictures that show the progression of your ideas. Storyboards are especially useful when you are working with genres like memoirs, reports, or proposals, because they help you visualize the “story.”

The easiest way to storyboard about your topic is to fold a regular piece of paper into four, six, or eight panels (Fig. 1.3). Then, in each of the panels, draw a scene or a major idea involving your topic. Stick figures are fine.

Storyboarding is similar to turning your ideas into a comic strip. You add panels to your storyboards and cross them out as your ideas evolve. You can also add dialogue into the scenes and put captions underneath each panel to show what is happening. Storyboarding often works best for people who like to think visually in drawings or pictures rather than in words and sentences.

Using Heuristics

You already use heuristics, but the term is probably not familiar to you. A heuristic is a discovery tool that helps you ask insightful questions or follow a specific pattern of thinking. Writers often memorize the heuristics that they find especially useful. Here, we will review some of the most popular heuristics, but many others are available.

The most common heuristic is a tool called the journalist’s questions, or sometimes called the “Five-W and How questions.” Writers for newspapers, magazines, and television use these questions to help them sort out the details of a story.

- Who was involved?

- What happened?

- When did it happen?

- Where did the event happen?

- Why did it happen?

- How did it happen?

Write each of these questions separately on your screen or a piece of paper. Then answer each one in as much detail as you can. Make sure your facts are accurate, so you can reconstruct the story from your notes. If you don’t know the answer to one of these questions, put down a question mark. A question mark signals a place where you might need to do some more research.

When using the Five-W and How questions, you might also find it helpful to ask, “What has changed recently about my topic?” Paying attention to change will also help you determine your angle on the topic (i.e., your unique perspective or view).

Writing Anxiety

“Writing anxiety” and “writer’s block” are informal terms for a wide variety of apprehensive and pessimistic feelings about writing. These feelings may not be pervasive in a person’s writing life. For example, you might feel perfectly fine writing a biology lab report but apprehensive about writing a paper on a novel. You may confidently tackle a paper about the sociology of gender but delete and start over twenty times when composing an email to a cute classmate suggesting coffee. In other words, writing anxiety and writers’ block are situational, according to Keith Hjortshoj. These terms do NOT describe psychological attributes. People aren’t born anxious writers; rather, they

become anxious or blocked through negative or difficult experiences with writing.

Although there is a great deal of variation among individuals, there are also some common experiences that writers in general find stressful. For example, you may struggle when you are:

- adjusting to a new form of writing—for example, first-year college writing, papers in a new field of study, or longer forms than you are used to (a long research paper, a senior thesis, a master’s thesis, a dissertation).

- writing for a reader or readers who have been overly critical or demanding in the past.

- remembering negative criticism received in the past—even if the reader who criticized your work won’t be reading your writing this time.

- working with limited time or with a lot of unstructured time.

- responding to an assignment that seems unrelated to academic or life goals.

- dealing with troubling events outside of school.

Strategies for Overcoming Writing Anxiety

Get Support

Choose a writing buddy, someone you trust to encourage you in your writing life. Your writing buddy might be a friend or family member, a classmate, a teacher, a colleague, or a Writing Center tutor. Talk to your writing buddy about your ideas, your writing process, your worries, and your successes. Share pieces of your writing. Make checking in with your writing buddy a regular part of your schedule. In his book Understanding Writing Blocks, Keith Hjortshoj describes how isolation can harm writers, particularly students who are working on long projects not connected with coursework. He suggests that in addition to connecting with supportive individuals, such students can benefit from forming or joining a writing group, which functions in much the same way as a writing buddy. A group can provide readers, deadlines, support, praise, and constructive criticism.

Identify Your Strengths

Often, writers who are experiencing block or anxiety have a worse opinion of their own writing than anyone else! Make a list of the things you do well. You might ask a friend or colleague to help you generate such a list. Here are some possibilities to get you started:

- I explain things well to people.

- I get people’s interest.

- I have strong opinions.

- I listen well.

- I am critical of what I read.

- I see connections.

Choose at least one strength as your starting point. Instead of saying “I can’t write,” say “I am a writer who can …”

Recognize that Writing is a Complex Process

Writing is an attempt to fix meaning on the page, but you know, and your readers know, that there is always more to be said on a topic. The best writers can do is to contribute what they know and feel about a topic at a particular point in time. Writers often seek “flow,” which usually entails some sort of breakthrough followed by a

beautifully coherent outpouring of knowledge. Flow is both a possibility—most people experience it at some point in their writing lives—and a myth. Inevitably, if you write over a long period of time and for many different situations, you will encounter obstacles. As Hjortshoj explains, obstacles are particularly common during times of transition—transitions to new writing roles or to new kinds of writing.

Think of Yourself as an Apprentice

If block or apprehension is new for you, take time to understand the situations you are writing in. In particular, try to figure out what has changed in your writing life. Here are some possibilities:

- You are writing in a new format.

- You are writing longer papers than before.

- You are writing for new audiences.

- You are writing about new subject matter.

- You are turning in writing from different stages of the writing process—for example, planning stages or early drafts.

It makes sense to have trouble when dealing with a situation for the first time. It’s also likely that when you confront these new situations, you will learn and grow. Writing in new situations can be rewarding. Not every format or audience will be right for you, but you won’t know which ones might be right until you try them. Think of new writing situations as apprenticeships. When you’re doing a new kind of writing, learn as much as you can about it, gain as many skills in that area as you can, and when you finish the apprenticeship, decide which of the skills you learned will serve you well later on. You might be surprised.

Below are some suggestions for how to learn about new kinds of writing:

- Ask a lot of questions of people who are more experienced with this kind of writing. Here are some of the questions you might ask: What’s the purpose of this kind of writing? Who’s the audience? What are the most important elements to include? What’s not as important? How do you get started? How do you know when what you’ve written is good enough? How did you learn to write this way?

- Ask a lot of questions of the person who assigned you a piece of writing. If you have a paper, the best place to start is with the written assignment itself.

- Look for examples of this kind of writing. (You can ask your instructor if he/she could recommend an example). Look, especially, for variation. There are often many different ways to write within a particular form. Look for ways that feel familiar to you, approaches that you like. You might want to look for published models or, if this seems too intimidating, look at your classmates’ writing. In either case, ask yourself questions about what these writers are doing, and take notes. How does the writer begin and end? In what order does the writer tell things? How and when does the writer convey her or his main point? How does the writer bring in other people’s ideas? What is the writer’s purpose? How does she or he achieve that purpose?

- Most importantly, don’t try to do everything at once. Start with reasonable expectations. You can’t write like an expert your first time out. Nobody does! Use the criticism you get.

Try New Tactics When You Get Stuck

Often, writing blocks occur at particular stages of the writing process. The writing process is cyclical and variable. For different writers, the process may include reading, brainstorming, drafting, getting feedback, revising, and editing. These stages do not always happen in this order, and once a writer has been through a particular stage, chances are she or he hasn’t seen the last of that stage. For example, brainstorming may occur all along the way.

Figure out what your writing process looks like and whether there’s a particular stage where you tend to get stuck. Perhaps you love researching and taking notes on what you read, and you have a hard time moving from that work to getting started on your own first draft. Or once you have a draft, it seems set in stone and even though readers are asking you questions and making suggestions, you don’t know how to go back in and change it. Or just the opposite may

be true; you revise and revise and don’t want to let the paper go.

Wherever you have trouble, take a longer look at what you do and what you might try. Sometimes what you do is working for you; it’s just a slow and difficult process. Other times, what you do may not be working; these are the times when you can look around for other approaches to try:

Talk to your writing buddy and to other colleagues about what they do at the particular stage that gets you stuck.

Read about possible new approaches in our handouts on brainstorming and revising.

Try thinking of yourself as an apprentice to a stage of the writing process and give different strategies a shot.

Cut your paper into pieces and tape them to the wall, use eight different colors of highlighters, draw a picture of your paper, read your paper out loud in the voice of your

favorite movie star….

Okay, we’re kind of kidding with some of those last few suggestions, but there is no limit to what you can try. When it comes to conquering a block, give yourself permission to fall flat on your face. Trying and failing will you help you arrive at the thing that works for you.

Celebrate Your Successes

Start storing up positive experiences with writing. Whatever obstacles you’ve faced, celebrate the occasions when you overcome them. This could be something as simple as getting started, sharing your work with someone besides a teacher, revising a paper for the first time, trying out a new brainstorming strategy, or turning in a paper that has been particularly challenging for you. You define what a success is for you. Keep a log or journal of your writing successes and breakthroughs, how you did it, how you felt. This log can serve as a boost later in your writing life when you face new challenges.

Get Support

Wait a minute, didn’t we already say that? Yes. It’s worth repeating. Most people find relief for various kinds of anxieties by getting support from others. Sometimes the best person to help you through a spell of worry is someone who’s done that for you before—a family member, a friend, a mentor. Maybe you don’t even need to talk with this person about writing; maybe you just need to be reminded to believe in yourself, that you can do it.

If you don’t know anyone on campus yet whom you have this kind of relationship with, reach out to someone who seems like they could be a good listener and supportive. There are a number of professional resources for you on campus, people you can talk through your ideas or your worries with. A great place to start is the Student Success Center. If you know you have a problem with writing anxiety, make an appointment well before the paper is due. You can come to the Writing Center with a draft or even before you’ve started writing. You can also approach your instructor with questions about your writing assignment. Counselors at the Counseling Center are also available to talk with you about anxieties and concerns that extend beyond writing.

Apprehension about writing is a common condition on college campuses. Because writing is the most common means of sharing our knowledge, we put a lot of pressure on ourselves when we write. Talk with others; realize we’re all learning; take an occasional risk; turn to the people who believe in you. Counter negative experiences by actively creating positive ones.

Even after you have tried all of these strategies, invariably you will still have negative experiences in your writing life. When you get a paper back with a bad grade on it, fend off the negative aspects of that experience. Try not to let them sink in; try not to let your disappointment fester. Instead, jump right back in to some area of the writing process: choose one suggestion the evaluator has made and work on it, or read and discuss the paper with a friend or colleague, or do some writing or revising—on this or any paper—as quickly as possible.

Failures of various kinds are an inevitable part of the writing process. Without them, it would be difficult if not impossible to grow as a writer. Learning often occurs in the wake of a startling event, something that stirs you up, something that makes you wonder. Use your failures to keep moving.

the formulation and organization of ideas preparatory to writing during the first stage of the writing process

A diagram that depicts suggested relationships between concepts.

A prewriting technique in which a person writes continuously for a set period of time without worrying about rhetorical concerns or conventions and mechanics.

An informal way of generating ideas to write about or points to make about your topic.

Drawing a set of pictures that show the progression of your ideas.

A discovery tool that helps you ask insightful questions or follow a specific pattern of thinking.

The unique viewpoint, new information, or interesting take on a topic.