16

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Determine the source and nature of an arguable claim. (GEO 1; SLO 2, 4)

- Explain the term rhetoric and its history. (SLO 2, 3, 4; GEO 1, 2)

- Understand apply the elements of the rhetorical situation and rhetorical appeals. (SLO 3, 4; GEO 2)

- Use reasoning, authority, and emotion to support your argument. (GEO 1; SLO 2, 4)

- Identify and avoid logical fallacies. (GEO 1; SLO 2, 4)

For some people, the word argument brings up images of finger-pointing, hostility, or polarization. Actually, when people behave like this, they really aren’t arguing at all. They are quarreling. And when people quarrel, they are no longer listening to or considering each other’s ideas.

An argument is something quite different. Arguments involve making reasonable claims and then backing up those claims with evidence and support. The objective of an argument is not necessarily to “win” or prove that you are right and others are wrong. Instead, your primary goal is to show others that you are probably right or that your beliefs are reasonable and worthy of their honest consideration. When arguing, both sides attempt to convince others that their position is stronger or more beneficial. Their goal is to reach an agreement or compromise.

In college and in the professional world, people use argument to think through ideas and debate uncertainties. Arguments are about getting things done by gaining the cooperation of others. In most situations, an argument is about agreeing as much as disagreeing, about cooperating with others as much as competing with them. Your ability to argue effectively will be an important part of your success in your college courses, your social life, and your career.

What Is Arguable?

Let’s begin by first discussing what is “arguable.” Some people will say that you can argue about anything. And in a sense, they are right. We can argue about anything, no matter how trivial or pointless.

| “I don’t like chocolate.” | “Yes, you do.” |

| “The American Civil War began in 1861.” | “No, it didn’t.” |

| “It disgusts me that our animal shelter kills unclaimed pets after just two weeks.” | “No, it doesn’t. You think it’s a good thing.” |

These kinds of arguments are rarely worth your time and effort. Of course, we can argue that our friend is lying when she says she doesn’t like chocolate, and we can challenge the historical fact that the Civil War really started in 1861. However, debates about personal judgments, such as liking or not liking something, quickly devolve into “Yes, I do.” “No, you don’t!” kinds of quarrels. Meanwhile, debates about proven facts, like the year the American Civil War started, can be resolved by consulting a trusted source. To be truly arguable, a claim should exist somewhere between personal judgments and proven facts (Figure 8.1).

Arguable Claims

When laying the groundwork for an argument, you need to first define an arguable claim that you want to persuade your readers to accept as probably true. For example, here are arguable claims on two sides of the same topic:

Examples of Arguable Claims

Marijuana should be made a legal medical option in our state because there is overwhelming evidence that marijuana is one of the most effective treatments for pain, nausea, and other symptoms of widespread debilitating diseases, such as multiple sclerosis, cancer, and some kinds of epilepsy.

Although marijuana can relieve symptoms associated with certain diseases, it should not become a legal medical option because its medical effectiveness has not been clinically proven and because legalization would send a message that recreational drugs are safe and even beneficial to health.

Both claims are “arguable” because neither side can prove that it is factually right or that the other side is factually wrong. Meanwhile, neither side is based exclusively on personal judgments. Instead, both sides want to persuade you, the reader, that they are probably right.

When you invent and draft an argument, your goal is to support your position to the best of your ability, but you should also imagine views and viewpoints that disagree with yours. Keeping opposing views in mind will help you clarify your ideas, anticipate counterarguments, and identify the weaknesses of your position. Then, when you draft your argument, you will be able to show readers that you have considered all sides fairly.

On the other hand, if you realize that an opposing position does not really exist or that it’s very weak, then you may not have an arguable claim in the first place.

Four Sources of Arguable Claims

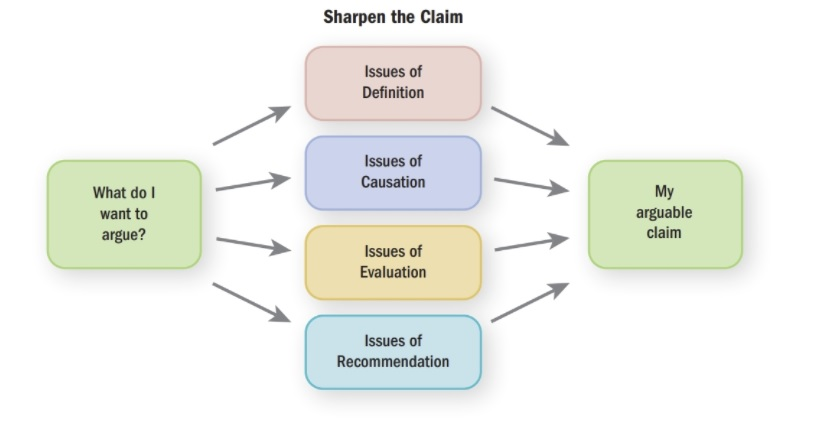

Once you have a rough idea of your arguable claim, you should refine and clarify it. First, figure out what you want to argue. Then sharpen your claim by figuring out which type of argument you are making, as shown in the chart below. The result will be a much clearer arguable claim.

Arguable claims generally arise from four sources:

1. Issues of definition. Some arguments hinge on how to define an object, event, or person. For example, here are a few arguable claims that debate how to define something:

Examples

When our campus newspaper published its interview with that Holocaust denier, it was an act of journalistic malpractice.

What that fraternity did was not just a “prank that got out of hand.” At the very least, it was an act of bullying. More accurately, it was assault and battery.

A pregnant woman who smokes is a child abuser who needs to be stopped before she further harms her unborn child.

2. Issues of causation. Humans tend to see events in terms of cause and effect. Consequently, people often argue about whether one thing caused another.

Examples

Each year, texting while driving causes far more deaths than the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center.

Violent video games do not cause the people who play to become violent in their actual, lived, real-world lives.

Pregnant mothers who choose to smoke are responsible for an unacceptable number of birth defects in children.

3. Issues of evaluation. We also argue about whether something is good or bad, right or wrong, or better or worse.

Examples

It’s true that the movies inspired by Marvel Comics are funny and action-packed, but for great storytelling and drama, the movies inspired by DC Comics—such as Batman, Superman, and Wonder Woman—are unmatched.

The current U.S. taxation system is unfair, because the majority of taxes fall most heavily on people who work hard and corporations who are bringing innovative products to the marketplace.

Although both are dangerous, drinking alcohol in moderation while pregnant is less damaging to an unborn child than smoking in moderation.

4. Issues of recommendation. We also use arguments to make recommendations about the best course of action to follow. These kinds of claims are signaled by words like “should,” “must,” “ought to,” and so forth.

Examples

Tompson Industries should convert its Nebraska factory to renewable energy sources, like wind, solar, and geothermal, using the standard electric grid only as a backup supply for electricity.

People will keep texting while driving because the urge to stay in touch is so irresistible. Therefore, we need to make the penalties for breaking this law much harsher.

We must help pregnant women to stop smoking by developing smoking-cessation programs that are specifically targeted toward this population.

Rhetoric

The art of creating effective arguments is explained and systematized by a discipline called rhetoric. Writing is about making choices, and knowing the principles of rhetoric allows a writer to make informed choices about various aspects of the writing process. Every act of writing takes place in a specific rhetorical situation. Before looking closely at different definitions and components of rhetoric, let us try to understand what rhetoric is not. In recent years, the word “rhetoric” has developed a bad reputation in American popular culture. In the popular mind, the term “rhetoric” has come to mean something negative and deceptive. Open a newspaper or turn on the television, and you are likely to hear politicians accusing each other of “too much rhetoric and not enough substance.” According to this distorted view, rhetoric is verbal fluff, used to disguise empty or even deceitful arguments.

Examples of this misuse abound. Here are some examples:

- A 2003 CNN news article “North Korea Talks On Despite Rhetoric” describes the decision by the international community to continue the talks with North Korea about its nuclear arms program despite what the author sees as North Koreans’ “rhetorical blast” at a US official taking part in the talks. The implication here is that that, by verbally attacking the US official, the North Koreans attempted to hide the lack of substance in their argument. The word “rhetoric” in this context implies a strategy to deceive or distract.

- Another example is the title of the now-defunct political website “Spinsanity: Countering Rhetoric with Reason.” The website’s authors state that “engaged citizenry, active press and strong network of fact-checking websites and blogs can help turn the tide of deception that we now see.” (http://www.spinsanity.org). What this statement implies, of course, is that rhetoric is “spin” and that it is the opposite of truth.

- Here, perhaps, is the most interesting example. The author of the video below, posted on Youtube, is clearly dissatisfied with the abundance of “rhetoric” in Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign for the White House. What is interesting about this clip is that its author does not seem to realize that she is engaging in rhetoric as she is criticizing the term. She has a purpose, which is to question Obama’s credentials; she is addressing an audience which consists of people who are perhaps considering voting for Obama; finally, she is creating her video in a very real context of the heated battle between Senators Obama and Clinton for the Presidential nomination of the Democratic Party.

Rhetoric is not a dirty trick used by politicians to conceal and obscure, but an art, which, for many centuries, has had many definitions. Perhaps the most popular and overreaching definition comes to us from the Ancient Greek thinker Aristotle. Aristotle defined rhetoric as “the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion” (Poetics). Aristotle saw primarily as a practical tool, indispensable for civic discourse.

Elements of the Rhetorical Situation: Context, Audience, and Purpose

When composing, every writer must take into account the conditions under which the writing is produced and will be read. It is customary to represent the three key elements of the rhetorical situation as a triangle of writer, reader, and text, or, as “communicator,” “audience,” and “message.”

The three elements of the rhetorical situation are in a constant and dynamic interrelation. All three are also necessary for communication through writing to take place. For example, if the writer is taken out of this equation, the text will not be created. Similarly, eliminating the text itself will leave us with the reader and writer, but without any means of conveying ideas between them, and so on.

Moreover, changing one or more characteristics of any of the elements depicted in the figure above will change the other elements as well. For example, with the change in the beliefs and values of the audience, the message will also likely change to accommodate those new beliefs, and so on.

In his discussion of rhetoric, Aristotle states that writing’s primary purpose is persuasion. Other ancient rhetoricians’ theories expand the scope of rhetoric by adding new definitions, purposes, and methods. For example, another Greek philosopher and rhetorician Plato saw rhetoric as a means of discovering the truth, including personal truth, through dialog and discussion. According to Plato, rhetoric can be directed outward (at readers or listeners), or inward (at the writer him or herself). In the latter case, the purpose of rhetoric is to help the author discover something important about his or her own experience and life.

The third major rhetorical school of Ancient Greece whose views have profoundly influenced our understanding of rhetoric were the Sophists. The Sophists were teachers of rhetoric for hire. The primary goal of their activities was to teach skills and strategies for effective speaking and writing. Many Sophists claimed that they could make anyone into an effective rhetorician. In their most extreme variety, Sophistic rhetoric claims that virtually anything could be proven if the rhetorician has the right skills. The legacy of Sophistic rhetoric is controversial. Some scholars, including Plato himself, have accused the Sophists of bending ethical standards in order to achieve their goals, while others have praised them for promoting democracy and civic participation through argumentative discourse.

What do these various definitions of rhetoric have to do with research writing? Everything! If you have ever had trouble with a writing assignment, chances are it was because you could not figure out the assignment’s purpose. Or, perhaps you did not understand very well whom your writing was supposed to appeal to. It is hard to commit to purposeless writing done for no one in particular.

Research is not a very useful activity if it is done for its own sake. If you think of a situation in your own life where you had to do any kind of research, you probably

had a purpose that the research helped you to accomplish. You could, for example, have been considering buying a car and wanted to know which make and model would suit you best. Or, you could have been looking for an apartment to rent and wanted to get the best deal for your money. Or, perhaps your family was planning a vacation and researched the best deals on hotels, airfares, and rental cars. Even in these simple examples of research that are far simpler than research

most writers conduct, you as a researcher were guided by some overriding purpose. You researched because you had a purpose to accomplish.

The three main elements of the rhetorical situation are purpose, audience, and context. We will look at these elements primarily through the lens of Classical Rhetoric, the rhetoric of Ancient Greece and Rome. Principles of classical rhetoric (albeit some of them modified) are widely accepted across modern Western civilization. Classical rhetoric provides a solid framework for analysis and production of effective texts in a variety of situations.

Purpose

Good writing always serves a purpose. Texts are created to persuade, entertain, inform, instruct, and so on. In a real writing situation, these discrete purposes are often combined.

Audience

The second key element of the rhetorical approach to writing is audience-awareness. As you saw from the rhetorical triangle earlier in this chapter, readers are an indispensable part of the rhetorical equation, and it is essential for every writer to understand their audience and tailor his or her message to the audience’s needs.

The key principles that every writer needs to follow in order to reach and affect his or her audience are as follows:

- Have a clear idea about who your readers will be.

- Understand your readers’ previous experiences, knowledge, biases, and expectations and how these factors can influence their reception of your argument.

- When writing, keep in mind not only those readers who are physically present or whom you know (your classmates and instructor), but all readers who would benefit from or be influenced by your argument.

- Choose a style, tone, and medium of presentation appropriate for your intended audience.

Context

Context is an important part of the rhetorical situation. Writers do not work in a vacuum. Instead, the content, form, and reception of their work by readers are heavily influenced by the conditions in society as well as by the personal situations of their readers. These conditions in which texts are created and read affect every aspect of writing and every stage of the writing process, from topic selection to decisions about what kinds of arguments used and their arrangement, to the writing style, voice, and persona which the writer wishes to project in his or her writing. All elements of the rhetorical situation work together in a dynamic relationship. Therefore, awareness of rhetorical occasion and other elements of the context of your writing will also help you refine your purpose and understand your audience better. Similarly having a clear purpose in mind when writing and knowing your audience will help you understand the context in which you are writing and in which your work will be read better.

One aspect of writing where you can immediately benefit from understanding context and using it to your rhetorical advantage is the selection of topics for your compositions. Any topic can be good or bad, and a key factor in deciding on whether it fits the occasion. In order to understand whether a particular topic is suitable for a composition, it is useful to analyze whether the composition would address an issue, or a rhetorical exigency when created. The writing activity below can help you select topics and issues for written arguments.

To understand how writers can study and use occasion in order to make effective arguments, let us examine another ancient rhetorical concept. Kairos is one of the most fascinating terms from Classical rhetoric. It signifies the right or opportune moment for an argument to be made. It is such a moment or time when the subject of the argument is particularly urgent or important and when audiences are more likely to be persuaded by it. Ancient rhetoricians believed that if the moment for the argument is right (for instance, if there are conditions in society that would make the audience more receptive to the argument), the rhetorician would have more success persuading such an audience.

Rhetorical Appeals: Logos, Ethos, and Pathos

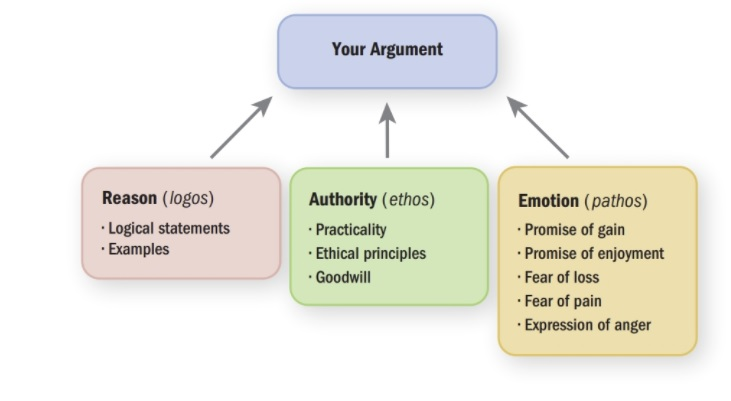

Once you have developed an arguable claim, you can start figuring out how you are going to support it. A solid argument will usually employ three types of “proofs”: reason, authority, and emotion, as seen in the chart below. Greek rhetoricians like Aristotle originally used the words logos (reason), ethos (authority), and pathos (emotion) (Fig 8.1) to discuss these three proofs.

Logos (Logos)

Logos involves appealing to your readers’ sense of logic and reason.

Logical Statements

Logical statements allow you to use your readers’ existing beliefs to prove they should agree with a further claim. Here are some common patterns for logical statements:

- If . . . then: “If you believe X, then you should believe Y also.”

- Either . . . or: “Either you believe X, or you believe Y.”

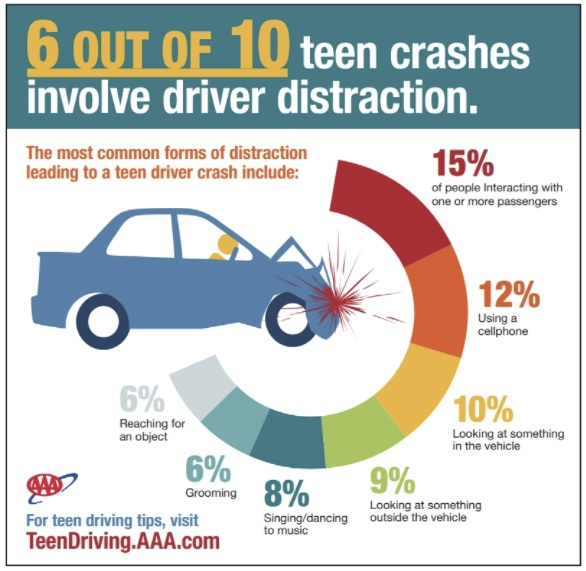

- Cause and effect: “X is the reason Y happens.” (Figure 8.1)

- Costs and benefits: “The benefits of doing X are worth/not worth the cost of Y.”

- Better and worse: “X is better/worse than Y because . . . “

Examples

The second type of reasoning, examples, allows you to illustrate your points or demonstrate that a pattern exists.

- Examples: “For example, in 1994. . . .” “For instance, last week. . . .” “To illustrate, there was the interesting case of. . . .” “Specifically, I can name two situations when. . . .”

- Personal experiences: “Last summer, I saw. . . .” “Where I work, X happens regularly.”

- Facts and data: “According to our survey results, . . . .” “Recently published data show that. . . .”

- Patterns of experiences: “X happened in 2004, 2008, and 2012. Therefore, we expect it to happen again in 2016.” “In the past, each time X happened, Y has happened also.”

- Quotes from experts: “Dr. Jennifer Xu, a scientist at Los Alamos National Laboratory, recently stated. . . .” “In his 2013 article, historian George Brenden claimed. . . .”

Ethos (Ethos)

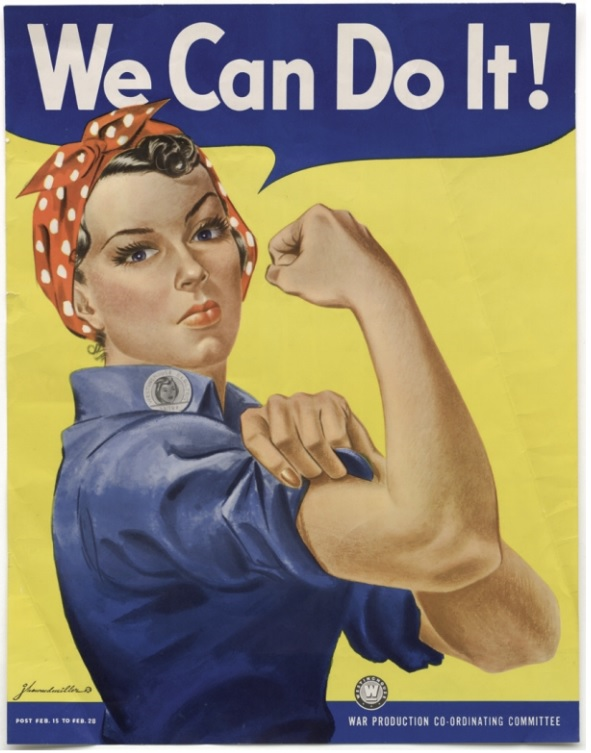

Ethos involves using your own experience or the reputations of others to support your arguments (Figure 8.2). Another way to strengthen your authority is to demonstrate your practicality, ethical principles, and goodwill. These three types of authority were first mentioned by Aristotle as a way to show that a speaker or writer is being fair and therefore credible. These strategies still work well today.

Practicality

Show your readers that you are primarily concerned about solving problems and getting things done, not lecturing, theorizing, or simply winning. Where appropriate, admit that the issue is complicated and cannot be fixed easily. You can also point out that reasonable people can disagree about the issue. Being “practical” involves being realistic about what is possible, not idealistically pure about what would happen in a perfect world.

- Personal experience: “I have experienced X, so I know it’s true and Y is not.”

- Personal credentials: “I have a degree in Z” or “I am the director of Y, so I know about the subject of X.”

- Appeal to experts: “According to Z, who is an expert on this topic, X is true and Y is not true.”

- Admission of limitations: “I may not know much about Z, but I do know that X is true and Y is not.”

Ethical Principles

Demonstrate that you are arguing for an outcome that meets a specific set of ethical principles. An ethical argument can be based on any of three types of ethics:

- Rights: Using human rights or constitutional rights to back up your claims.

- Laws: Showing that your argument is in line with civic laws.

- Utilitarianism: Arguing that your position is more beneficial for the majority of people.

In some situations, you can demonstrate that your position is in line with your own and your readers’ religious beliefs or other deeply held values.

- Good moral character: “I have always done the right thing for the right reasons, so you should believe me when I say that X is the best path to follow.”

Goodwill

Demonstrate that you have your readers’ interests in mind, not just your own. Of course, you may be arguing for something that affects you personally or something you care about. So show your readers that you care about their needs and interests, too. Let them know that you understand their concerns and that your position is fair or a “win-win” for both you and them.

- Identification with the readers: “You and I come from similar backgrounds and we have similar values; therefore, you would likely agree with me that X is true and Y is not.”

- Expression of goodwill: “I want what is best for you, so I am recommending X as the best path to follow.”

- Use of “insider” language: Using special terminology or referring to information that only insiders would understand.

Pathos (Pathos)

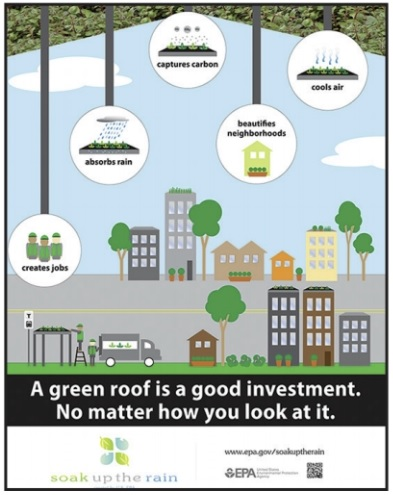

Using emotional appeals to persuade your readers is appropriate if the feelings you draw on are suitable for your topic and readers (Figure 8.4). As you develop your argument, think about how your emotions and those of your readers might influence how their decisions will be made.

- Promise of gain. Demonstrate to your readers that agreeing with your position will help them gain things they need or want, like trust, time, money, love, loyalty, advancement, reputation, comfort, popularity, health, beauty, or convenience (Figure 8.5). “By agreeing with us, you will gain trust, time, money, love, advancement, reputation, comfort, popularity, health, beauty, or convenience.”

- Promise of enjoyment. Show that accepting your position will lead to more satisfaction, including joy, anticipation, surprise, pleasure, leisure, or freedom. “If you do things our way, you will experience joy, anticipation, fun, surprises, enjoyment, pleasure, leisure, or freedom.”

- Fear of loss. Suggest that not agreeing with your opinion might cause the loss of things readers value, like time, money, love, security, freedom, reputation, popularity, health, or beauty. “If you don’t do things this way, you risk losing time, money, love, security, freedom, reputation, popularity, health, or beauty.”

- Fear of pain. Imply that not agreeing with your position will cause feelings of pain, sadness, frustration, humiliation, embarrassment, loneliness, regret, shame, vulnerability, or worry. “If you don’t do things this way, you may feel pain, sadness, grief, frustration, humiliation, embarrassment, loneliness, regret, shame, vulnerability, or worry.”

- Expressions of anger or disgust. Show that you share feelings of anger or disgust with your readers about a particular event or situation. “You should be angry or disgusted because X is unfair to you, me, or someone else.”

The psychologist Robert Plutchik suggests there are eight basic emotions: joy, acceptance, fear, surprise, sadness, disgust, anger, and anticipation (Fig. 8.5). Some other common emotions that you might find are annoyance, awe, calmness, confidence, courage, delight, disappointment, embarrassment, envy, frustration, gladness, grief, happiness, hate, hope, horror, humility, impatience, inspiration, jealousy, joy, loneliness, love, lust, nervousness, nostalgia, paranoia, peace, pity, pride, rage, regret, resentment, shame, shock, sorrow, suffering, thrill, vulnerability, worry, and yearning.

Begin by listing the positive and negative emotions that are associated with your topic or with your side of the argument. Use positive emotions as much as you can, because they will build a sense of goodwill, loyalty, or happiness in your readers. Show readers that your position will bring them respect, gain, enjoyment, or pleasure. Negative emotions should be used sparingly. Negative emotions can energize your readers or spur them to action. However, be careful not to threaten or frighten your readers, because people tend to reject bullying or scare tactics. These moves will undermine your attempts to build goodwill. Make sure that any feelings of anger or disgust you express in your argument would be shared by your readers, or they will reject your argument as unfair, harsh, or reactionary.

Avoid Fallacies

Avoid Fallacies

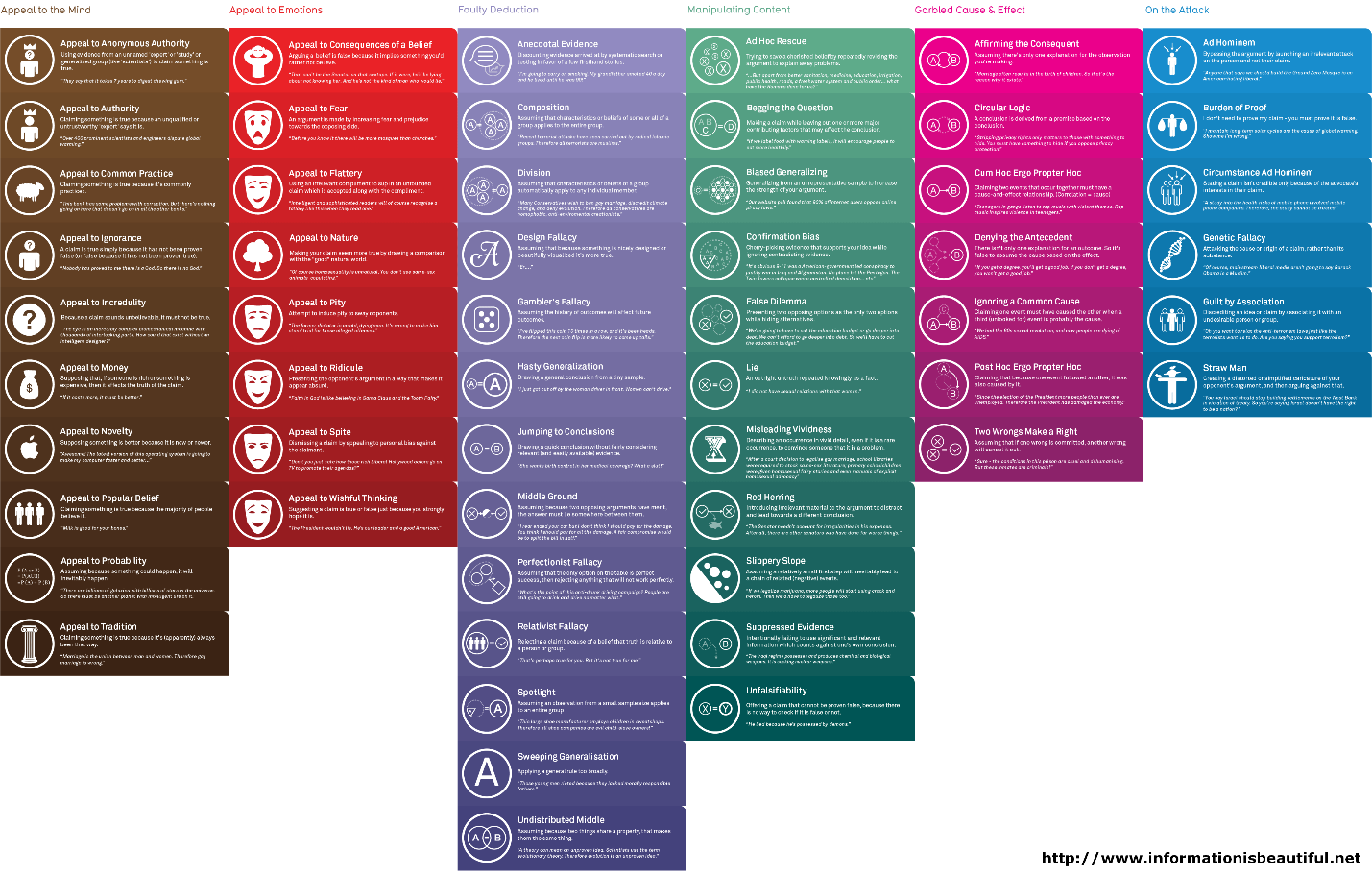

A logical fallacy is an error in reasoning. You should avoid logical fallacies in your own writing because they can undermine your argument. Plus, they can keep you from gaining a full understanding of the issue because fallacies usually lead to inaccurate or ambiguous conclusions. Figure 8.6 defines and gives examples of common logical fallacies. Watch out for them in your own arguments. When an opposing viewpoint depends on a logical fallacy, you can point to it as a weakness.

Fallacies tend to occur for three primary reasons:

- False or weak premises. In these situations, the author is overreaching to make a point. The argument uses false or weak premises (bandwagon, post hoc reasoning, slippery slope, or hasty generalization), or it relies on comparisons or authorities that are inappropriate (weak analogy, false authority).

- Irrelevance. The author is trying to distract readers by using name-calling (ad hominem) or bringing up issues that are beside the point (red herring, tu quoque, non sequitur).

- Ambiguity. The author is clouding the issue by using circular reasoning (begging the question), arguing against a position that no one is defending (straw man), or presenting the reader with an unreasonable choice of options (either/or). Logical fallacies do not prove that someone is wrong about a topic. They simply mean that the person may be using weak or improper reasoning to reach his or her conclusions. In some cases, logical fallacies are used deliberately. For instance, some advertisers want to slip a sales pitch past the audience. Savvy arguers can also use logical fallacies to trip up their opponents. When you learn to recognize these fallacies, you can counter them as necessary.

In addition to fallacies of logic, it’s important to be aware of fallacies of ethos and pathos. Check out more examples of rhetological fallacies at https://informationisbeautiful.net/visualizations/rhetological-fallacies/.

A series of statements, called the premises, intended to determine the degree of truth of another statement, the conclusion

A statement of the exact meaning of a word or idea.

Influence by which one event, process or state contributes to the production of another event, process or state where the cause is partly responsible for the effect, and the effect is partly dependent on the cause.

The making of a judgment about the amount, number, or value of something; assessment.

The making of a judgment about the amount, number, or value of something; assessment.

(385-323 BCE) a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato and mentor to Alexander the Great, he was the founder of the Lyceum, the Peripatetic school of philosophy, and the Aristotelian tradition.

The manner of expressing thought in language characteristic of an individual, period, school, or nation.

The general feeling or attitude of a piece of writing.

The method of communication that an author uses to disseminate their message. Plural: media.

A rhetorical appeal to logic, reason, and common sense.

A rhetorical appeal to authority, credibility, and character.

A rhetorical appeal to emotion.

Moral principles that govern a person's behavior or the conducting of an activity.

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Use reliable strategies to find electronic sources. (GEO 1; SLO 2)

- Collect evidence from a variety of print sources. (GEO 1; SLO 2)

- Do your own empirical research with interviews, surveys, and field observations. (GEO 1, 2; SLO 2)

A research plan should begin after you can clearly identify the focus of your argument. First, inform yourself about the basics of your topic (Wikipedia and general online searches are great starting points). Be sure you’ve read all the assigned texts and carefully read the prompt as you gather preliminary information. This stage is sometimes called pre-research.

A broad online search will yield thousands of sources, which no one could be expected to read through. To make it easier on yourself, the next step is to narrow your focus. Think about what kind of position or stance you can take on the topic. What about it strikes you as most interesting? Refer back to the prewriting stage of the writing process, which will come in handy here.

Finding Electronic and Online Sources

The Internet is a good place to start researching your topic. Keep in mind, though, that the Internet is not the only place to do research. You should use print and empirical sources to triangulate the evidence you find on the Internet.

Using Internet Search Engines

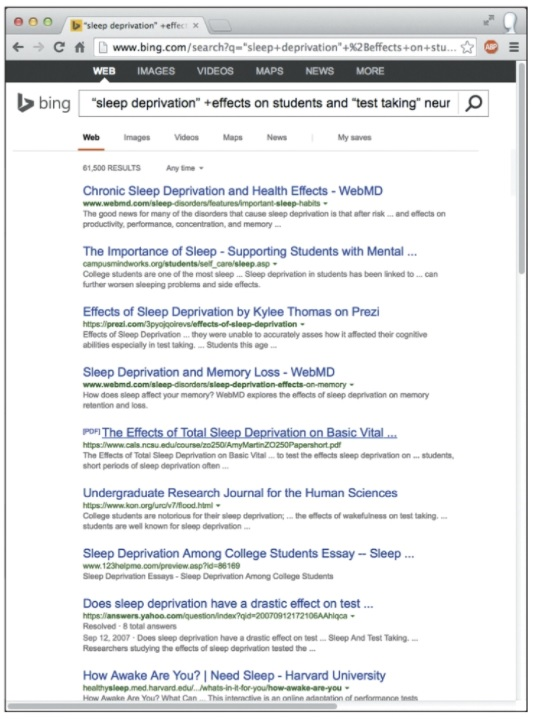

Search engines let you use keywords to locate information about your topic. If you type your topic into Google, Bing, or Yahoo!, the search engine will return many thousands of sites. With a few easy tricks, though, you can target your search with some common symbols and strategies.

For example, let’s say you are researching how sleep deprivation affects college students. You might start by entering the phrase:

sleep deprivation

You will get many more results than you need, and they may not all apply to college students. To narrow down your search results, add another keyword using the word “and.”

sleep deprivation and college students

With this generic subject, a search engine will pull up millions of Web pages that might refer to this topic. Of course, there is no way you are going to have time to look through all those sites to find useful evidence, even if the search engine ranks them for you.

So you need to target your search to pull up only the kinds of materials you want. Here are some tips for getting better results:

- Use exact words. Choose words that exactly target your topic, and use as many as you need to sharpen your results. For example:

- sleep deprivation effects on students test taking

- Use quotation (“ ”) marks. If you want to find a specific phrase, use quotation marks to target those phrases.

- “sleep deprivation” effects on students and “test taking”

- Use brackets ([ ]). If you want to search for phrases in any order (contrary to using quotation marks, brackets will do that for you.

- “sleep deprivation” [causes and effects]

- Use the plus (+) sign. If you put a plus (+) sign in front of a word, the search engine will only find pages that have that exact word in them.

- sleep +deprivation effects on +students +test +taking

- Use the minus (-) sign. If you want to eliminate any pages that refer to words or phrases you don’t want to see, you can use the minus sign to eliminate pages that refer to them.

- sleep deprivation +effects on students +test +taking -insomnia -apnea

- Use wildcard symbols. Some search engines have symbols for “wildcards,” such as ?, *, or %. These symbols are helpful when you know most of a phrase, but not all of it. For example, by using the prefix “neuro” followed by the wildcard symbol, a search engine will list results with the words neurology, neuroscience, neurobiology, neuropsychology, neurons, neurologist, etc. This can compile results from a spectrum of search terms at once.

- “sleep deprivation” +neuro*

- Use “or.” This will search for either topic at once. For example, the below search terms will search for results with “sleep deprivation” +students AND “sleep deprivation” +college at the same time.

- “sleep deprivation” +students or college

- Use a tilde (~). A tilde will search for a word as well as its synonyms. This avoids having to do multiple searches for similar terms. For example, the search below will not only find results with the word college, but associated words such as university and higher education.

- “sleep deprivation” and ~college

- Find related results. It’s easy to search for your terms in addition to ones related to what you are looking for. Let’s say you want to search for conditions related to sleep deprivation. By using the word “related,” the search engine will also show you results containing topics like insomnia or sleep medications.

- “college students” and related: “sleep deprivation”

- Search specific sites. If you know a web site that you would like a search, you can search within that site using a search engine. For example, let’s say that early in your research process you remember seeing a great article on sleep deprivation in college students from The Atlantic. However, you don’t remember the title of the article, who wrote it, or when it was written. No problem! You can easily find what you are looking with the following search terms:

- “sleep deprivation” site: theatlantic.com

- Search for specific files. If you are looking for presentations on your topic, for instance, you may wish to search for files ending in “.pptx” (PowerPoint). You can search for any file type, such as a PDF or image file such as JPEG. Simply use the word “file” and the file type (what comes after a file name).

- “sleep deprivation” file:.pptx

- Search for specific dates. If you are looking for information that was published during a certain time, you can do so by entering the date range with two periods between them. This is especially useful if you are only looking for current results or if you want information from a certain point in history.

- “sleep deprivation” 2010..2020

These search engine tips will help you pull up the pages you need. Figure 12.1 shows the results of a Bing search using the phrase:

“sleep deprivation” effects on students “test taking” −insomnia –apnea

Note that the first items pulled up by some search engines may be sponsored links. In other words, these companies paid to have their links show up at the top of your list. Most search engines highlight these links in a special way. You might find these links useful, but keep in mind that the sponsors are biased because they probably want to sell you something.

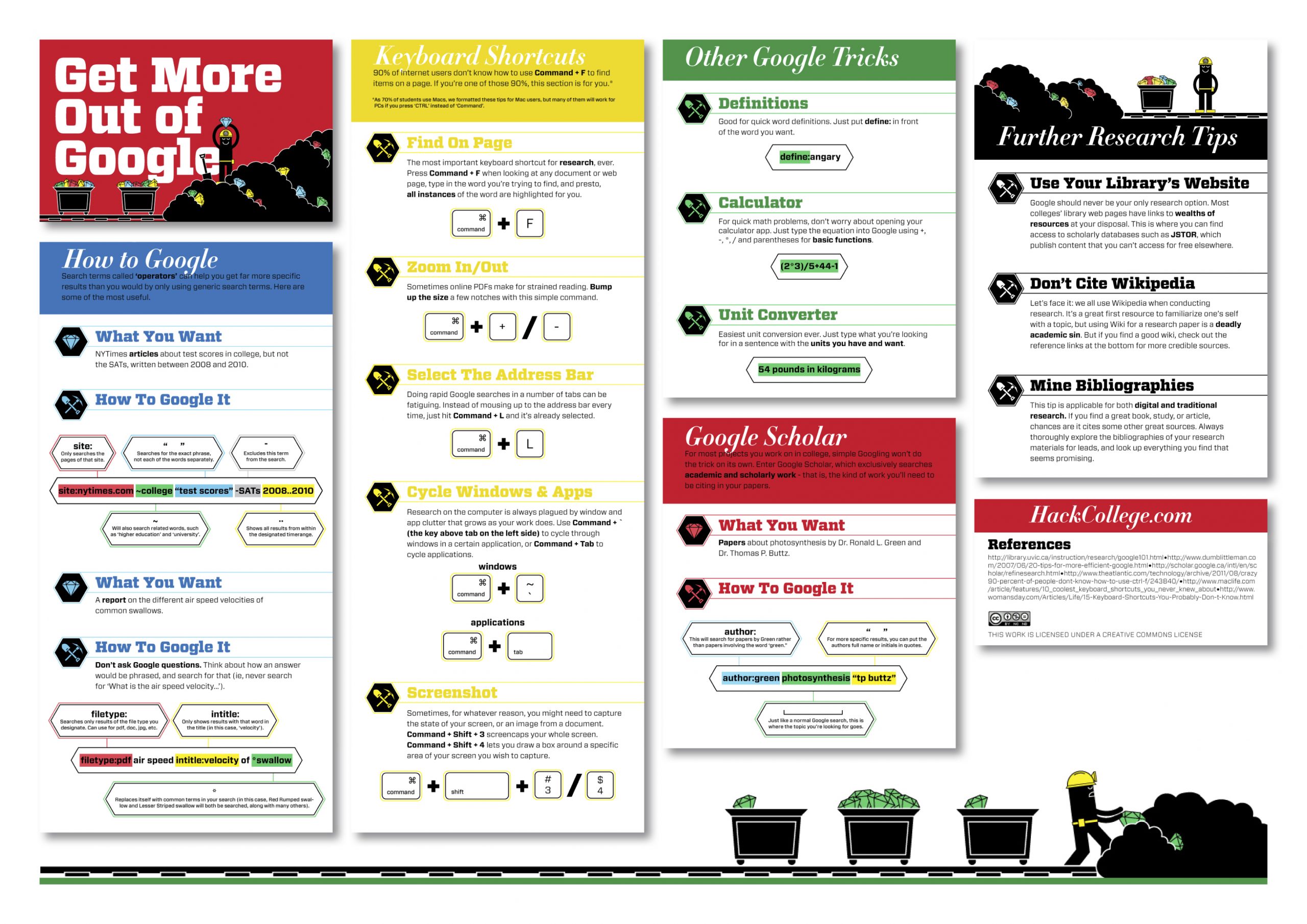

Lastly, while some search engines allow for you to search using whole sentences or questions (such as Google), others (such as databases) only allow for keyword searches. That means if you search Google for “What is the leading cause of sleep deprivation in college students?” you will probably find some worthy results. However, if you typed the same question into a database, you would not find any results because the search contains too many keywords. Therefore, it is important to know how to search using keywords and the symbols to better search any engine. The infographic below outlines some of Google’s helpful search features.

Google Scholar

An increasingly popular article database is Google Scholar. It looks like a regular Google search, and it aims to include the vast majority of scholarly sources available. While it has some limitations (like not including a list of which journals they include), it’s a very useful tool if you want to cast a wide net.

Here are three tips for using Google Scholar effectively:

- Add your topic field (economics, psychology, French, etc.) as one of your keywords. If you just put in “crime,” for example, Google Scholar will return all sorts of stuff from sociology, psychology, geography, and history. If your paper is on crime in French literature, your best sources may be buried under thousands of papers from other disciplines. A set of search terms like “crime French literature modern” will get you to relevant sources much faster.

- Don’t ever pay for an article. When you click on links to articles in Google Scholar, you may end up on a publisher’s site that tells you that you can download the article for $20 or $30. Don’t do it! You probably have access to virtually all the published academic literature through your library resources. Write down the key information (authors’ names, title, journal title, volume, issue number, year, page numbers) and go find the article through your library website. If you don’t have immediate full-text access, you may be able to get it through an inter-library loan.

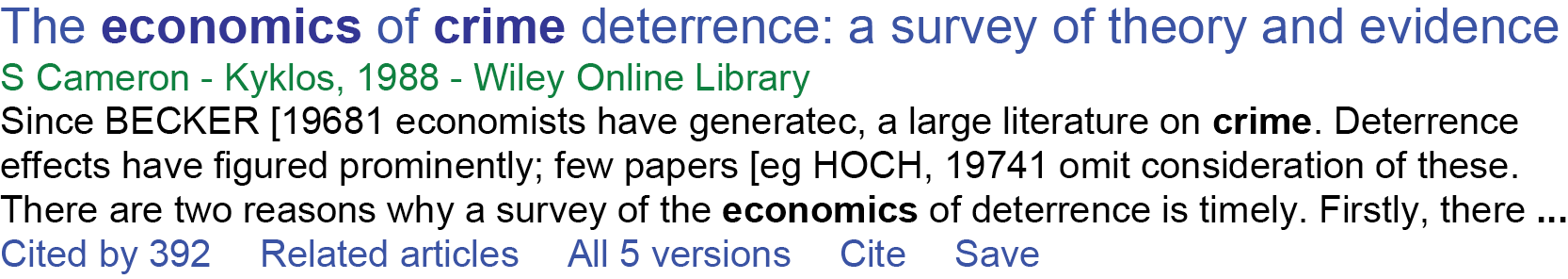

- Use the “cited by” feature. If you get one great hit on Google Scholar, you can quickly see a list of other papers that cited it. For example, the search terms “crime economics” yielded this hit for a 1988 paper that appeared in a journal called Kyklos:

Watch this video to get a better idea of how to utilize Google Scholar for finding articles. While this video shows specifics for setting up an account with Eastern Michigan University, the same principles apply to other colleges and universities. Ask your librarian if you have more questions.

Using the Internet Cautiously

Many of the so-called “facts” on the Internet are really just opinions and hearsay. Some stories are actually “fake news,” created to mislead people about important issues and current events. Also, many quotes that appear on the Internet have been taken out of context or corrupted in some way. So use information from the Internet critically and even skeptically. Don’t get fooled by a professional-looking Web site, because a good Web designer can make just about anything look professional. In the previous chapter (Chapter 11: Sources), you learned some questions for checking the reliability of any source.

The Internet will help you find plenty of useful, reliable evidence, but there is also a great amount of junk. It’s your responsibility as a researcher to critically evaluate what is reliable and what isn’t.

Using Documentaries and Television/Radio Broadcasts

Multimedia resources such as television and radio broadcasts are available online through network Web sites as well as sites like YouTube and Hulu. Depending on who made them, documentaries and broadcasts can be reliable sources. If the material is from a trustworthy source, you can take quotes and cite these kinds of electronic sources in your own work.

- Documentaries. A documentary is a nonfiction movie or program that relies on interviews and factual evidence about an event or issue. A documentary can be biased, though, so check into the background of the person or organization that made it.

- Television broadcasts. Cable channels and news networks like CNN, HBO, BBC, PBS, the History Channel, the National Geographic Channel, and the Biography Channel are producing excellent broadcasts that are reliable and can be cited as support for your argument. However, programs on news channels that feature just one or two highly opinionated commentators are less reliable because they tend to be sensationalistic and biased.

- Radio broadcasts. Radio broadcasts, too, can be informative and authoritative. Public radio broadcasts, such as those from National Public Radio and American RadioWorks, offer well-researched stories on the air and at their Web sites. On the other hand, political broadcasts like The Sean Hannity Show, The Rush Limbaugh Show, The Rachel Maddow Show, and The Thom Hartmann Show are often criticized for slanting the news and playing loose with the facts. You probably cannot rely on these broad-casts as factual sources in your argument.

Using Wikis, Blogs, and Podcasts

In the past, wikis, blogs, or podcasts were often considered too opinionated or subjective to be usable as sources for academic work. However, they are becoming increasingly reliable because reputable scholars and organizations are beginning to use these kinds of new media to publish research-based information. These electronic sources are especially helpful for defining issues and helping you locate other sources.

- Wikis. You already know about Wikipedia, the most popular wiki, but a variety of other wikis are available, like WikiHow, Wikibooks, and Wikitravel. Wikis allow their users to add and revise content, and they rely on other users to back-check facts. On some topics, such as popular culture (e.g., television programs, music, celebrities), a wiki might even be the best or only source of up-to-date information. On more established topics, however, you should always be skeptical about the reliability of the information because these sites are written anonymously and can be changed frequently. Your best approach is to use these sites primarily for start-up research on your topic and to find leads that will help you locate other, more reliable sources.

- Blogs. Blogs can be helpful for exploring a range of opinions on a particular topic. However, even some of the most established and respected blogs like Daily Kos, Power Line, and Wonkette are little more than opinionated commentaries on the day’s events. Blogs can help you identify the topic’s issues and locate more reliable sources; however, most blogs cannot be considered reliable sources themselves. If you want to use a blog as a source, you should explain in your paper why the author of the blog is a trusted source who is supporting the argument with reliable evidence.

- Podcasts. Most news Web sites offer podcasts and vidcasts, but the reliability of these sources depends on who made the audio or video file. Today, anyone with a mobile phone, digital recorder, or video camera can make a podcast, even a professional-looking podcast, so you need to carefully assess the credibility and experience of the person who made it.

On just about every topic, you will find plenty of people on the Internet who have opinions. The problem with online sources is that just about anyone can create or edit them. That’s why the Internet is a good place to start collecting evidence, but you need to also collect evidence from print and empirical sources to triangulate what you find online.

Finding Print Sources

With such easy access to electronic and online sources, people sometimes forget to look for print sources on their topic. That’s a big mistake. Print sources are typically the most reliable forms of evidence on just about any subject.

Locating Resources at Your Library

You can easily find useful books at your campus or local public library. More than likely, your university’s library Web site has an online search engine that you can access from any networked computer (Figure 12.2). This search engine will allow you to locate books in the library’s catalog. Also, your campus library will likely have research librarians who can help you find useful print sources. Ask for a research librarian at the library’s Information Desk.

- Books. The most reliable information on your topic can usually be found in books. Authors and editors of books work closely together to check their facts and gather the best evidence available. So books are usually more reliable than Web sites. The downside of books is that they tend to become outdated in fast-changing fields.

- Government publications. The US government produces an amazing amount of printed material on almost any topic you could imagine. Government Web sites, like The Catalog of U.S. Government Publications, are good places to find these sources. Your library probably collects many of these materials because they are usually free or inexpensive.

- Reference materials. The reference section of your library collects helpful reference tools, such as almanacs, directories, encyclopedias, handbooks, and guides. These reference materials can help you find facts, data, and evidence about people, places, and events.

Right now, entire libraries of books are being scanned and posted online. Out-of-copyright books are appearing in full-text versions as they become available. Online versions of copyrighted books are searchable, allowing you to see excerpts and identify pages on which you can locate the specific evidence you need.

Using the Library’s Databases

As we learned earlier, the strongest articles to support your academic writing projects will come from scholarly sources. Finding exactly what you need becomes specialized at this point, and requires a new set of searching strategies beyond even Google Scholar. For this kind of research, you’ll want to utilize library databases, as this video explains.

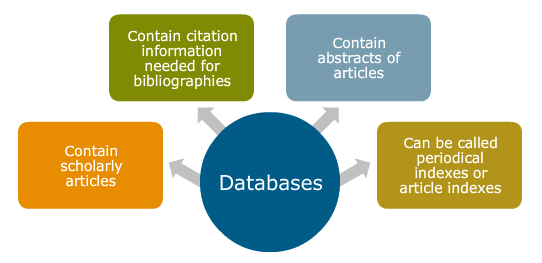

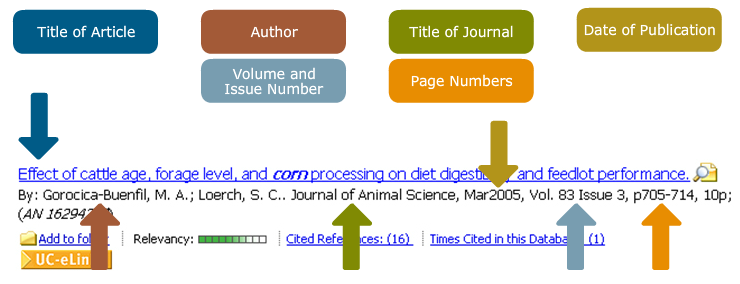

At your library, you can find articles in academic journals, magazines, and newspapers. These articles can be located using online databases or periodical indexes available through your library’s Web site. A database is a collection of searchable information. Databases can contain any type of source from photographs to sheet music to algebraic theorems, but most of your research using databases utilize the following sources:

- Academic journals. Articles in journals are usually written by scientists, professors, consultants, and subject matter experts (SMEs). These journals will offer some of the most exact information available on your topic. To find journal articles, start by searching in a periodical index related to your topic. Some of the more popular periodical indexes include:

- Magazines. You can find magazine articles about your topic in the databases. Print versions may be available in your library’s periodical or reference rooms.

- Newspapers. For research on current issues or local topics, newspapers often provide the most recent information. At your library or through its Web site, you can use newspaper indexes to search for information.

Finding Articles in Databases

The following video demonstrates how to search within a library database. The same general search tips apply to nearly all academic databases. Get familiar with your own school’s library homepage to identify the general search features, find databases, and practice searching for specific articles.

Tips for searching San Jac's Library Databases:

1. Go to the library’s website at www.sanjac.edu/library and select the tab that reads “Article Databases.”

2. Databases are grouped by subject, so if you are doing research for a course, you can find databases relevant to your coursework by selecting the corresponding subject from the menu. For example, if you are conducting research for a psychology course, you would find relevant databases by clicking on the subject called “Social & Behavioral Sciences.”

3. If you are doing pre-research or have not decided what topic you want to write about yet, you should start with a general database. These are located under the subject “Multi-Subject/General Research [These cover virtually every subject].” The best general research database at San Jac is the Academic Search Complete. The following video from North Virginia Community College demonstrates how to search using this database.

4. If you already know your topic, it may be best to continue to a subject-specific database. These are the databases we will be using in this course for our remaining essays:

- General Research: Academic Search Complete (located under “Multi-Subject/General Research [These cover virtually every subject]”

- Current Events: Newspaper Source Plus (located under “Newspapers & Other Primary Source Materials”)

- Historical Context: History Reference Center (located under “History”)

- Literature: Literary Reference Center, Literature Resource Center, Bloom’s Literary eBook Collection, Twayne’s Authors Series (located under “Literature”)

- Persuasion: Issues & Controversies, Opposing Viewpoints (located under “Multi-Subject/General Research [These cover virtually every subject]”

5. Remember to select “full text” when searching to avoid searching through results that do not have the actual text.

6. Utilize the search terms and symbols explained in the “Using Search Engines” section of this chapter. Pay attention to the types of sources you are required to use for your assignment. If sources must be current, then select a date range. If your sources must be peer-reviewed, check that box when searching. If you must use sources from academic journals, select that source type in the advanced search options.

7. When you find an article you may want to use or get back to in the future, use the tools menu in the database to download, save, print, or email the article. These tools will also formulate a citation for you, but they often contain errors, so it’s best to check these citations before using them in your essay. You will learn how to cite sources, including databases, in Section V of this textbook. If you are saving or sending the article’s link, be sure to use the permalink and not the URL in your browser.

8. If you are not having any luck finding a useful source, try different keywords or a different database. Chances are, there are multitudes of information on your topic available, you just need to know how to find them. If you still can’t find what you are looking for, contact the librarians. They maintain the databases and are specially trained to use them.

In a previous chapter (Chapter 11: Sources), you learned some of the pros and cons of using different types of sources. Databases are ultimately the best of both the electronic and print worlds. They are convenient and easy to use, like web sources. Databases also contain information that would not appear in Google search results because it is behind a paywall. Many publications charge subscription or access fees to read their content, but the databases that San Jac has purchased will allow you to access this content at no cost. Additionally, because most databases contain print media (i.e. journal, newspaper, and magazine articles) they are overall more reputable and trustworthy than the search results you will find on the web. You can access information exclusively from academics or other professionals and know exactly where it came it from.

Using Empirical Sources

Empirical sources include observations, experiments, surveys, and interviews. They are especially helpful for confirming or challenging the claims made in your electronic, online, and print sources. For example, if one of your electronic or online sources claims that “each day, college students watch an average of five hours of television but spend less than one hour on their homework,” you could use observations, interviews, or surveys to confirm or debunk that statement.

Interviewing People

Interviews are a great way to go behind the facts to explore the experiences of experts and regular people. Plus, interviewing others is a good way to collect quotes that you can add to your text. Here are some strategies for interviewing people:

Prepare For The Interview

1. Do your research. You need to know as much as possible about your topic before you interview someone about it. If you do not understand the topic before going into the interview, you will waste your own and your interviewee’s time by asking simplistic or flawed questions.

2. Create a list of three to five factual questions. Your research will probably turn up some facts that you want your interviewee to confirm or challenge.

3. Create a list of five to ten open-ended questions. Write down five to ten questions that cannot be answered with a simple “yes” or “no.” Your questions should urge the interviewee to offer a detailed explanation or opinion.

4. Decide how you will record the interview. Do you want to record the interview as a video or make an audio recording? Or do you want to take written notes? Each of these methods has its pros and cons. For example, audio recording captures the whole conversation, but interviewees are often more guarded about their answers when they are being recorded.

5. Set up the interview. The best place to do an interview is at a neutral site, like a classroom, a room in the library, or perhaps a café. The second best place is at the interviewee’s office. If necessary, you can do interviews over the phone.

Conduct The Interview

1. Explain the purpose of your project. Start out by describing your project to the interviewee and describe how the information from the interview will be used. Also, tell the interviewee how long you expect the interview will take.

2. Ask permission to record. If you are recording the interview in any way, ask permission to make the recording. First, ask if recording is all right before you turn on your device. Then, once you start recording, ask again so you record the interviewee’s permission.

3. Ask your factual questions first. Warm up the interviewee by asking questions that allow him or her to confirm or deny the facts you have already collected.

4. Ask your open-ended questions next. Ask the interviewee about his or her opinions, feelings, experiences, and views about the topic.

5. Ask if he or she would like to provide any other information. Often people want to tell you things you did not expect or know about. You can wrap up the interview by asking, “Is there anything else you would like to add about this topic?”

6. Thank the interviewee. Don’t forget to thank the interviewee for his or her time and information.

Interview Follow-Up

1. Write down everything you remember. As soon as possible after the interview, describe the interviewee in your notes and fill out any details you couldn’t write down during the interview. Do this even if you recorded the interview.

2. Get your quotes right. Clarify any direct quotations you collected from your interviewee. If you aren’t sure whether you got something right, you might e-mail your quotes to the interviewee for confirmation.

3. Back-check the facts. If the interviewee said something that was new to you or that conflicted with your prior research, use electronic, online, or print sources to back-check the facts. If there is a conflict, you can send an e-mail to the interviewee asking for clarification.

4. Send a thank-you note. Usually, an e-mail that thanks your interviewee is sufficient, but you might also send a card or brief letter of thanks.

Using an Informal Survey

Informal surveys are especially useful for generating data and gathering the views of many different people on the same questions. Many free online services such as SurveyMonkey, Survey Gizmo, and Zoomerang allow you to create and distribute your own surveys. They will also collect and tabulate the results for you. Here is how to create a useful, though not a scientific, survey:

1. Identify the population you want to survey. Some surveys target specific kinds of people (e.g., college students, women from ages 18–22, medical doctors). Others are designed to be filled out by anyone.

2. Develop your questions. Create a list of five to ten questions that can be answered quickly. Surveys typically use four basic types of questions: rating scales, multiple-choice, numeric open-ended, and text open-ended.

3. Check your questions for neutrality. Make sure your questions are as neutral as possible. Don’t lead on the people you are surveying with biased or slanted questions that fit your own beliefs.

4. Pilot-test your questions for clarity. Make sure your questions won’t confuse your survey takers. Before distributing your survey, ask a classmate or friend to take it and watch as he or she answers the questions. If your test subject struggles to answer any questions, you probably need to clarify them.

5. Distribute the survey. Ask a number of people to complete your survey, and note the kinds of people who agree to do it. Not everyone will be interested in completing your survey, so remember that your results might reflect the views of specific kinds of people.

6. Tabulate your results. When your surveys are returned, convert any quantitative responses into data. In written answers, pull out phrases and quotes that seem to reflect how the people you surveyed felt about your topic.

Professional researchers could point out that your informal survey is not objective and that your results are not statistically valid. That’s fine, as long as you are not using your survey to make important decisions or support claims about how people really feel. Your informal survey will still give you some helpful information about the opinions of others.

Doing Field Observations

Conducting a field observation can help you generate ideas and confirm facts. Field observations involve watching something closely and taking detailed notes.

1. Choose an appropriate location (field site). You want to choose a field site that allows you to see as much as possible, while not making it obvious that you are watching and taking notes. People will typically change their behavior if they think someone is watching them.

2. Take notes in a two-column format. A good field note technique is to use two columns to record what you see. On the left side, list the people, things, and events you observed. On the right side, write down how you interpret what you observed.

3. Use the Five-W and How questions. Keep notes about the who, what, where, when, why, and how elements that you observe. Try to include as much detail as possible.

4. Use your senses. Take notes about the things you see, hear, smell, touch, and taste while you are observing.

5. Pay attention to things that are moving or changing. Take special note of the things that moved or changed while you were observing, and what caused them to do so.

When you are finished taking notes, spend some time interpreting what you observed. Look for patterns in your observations to help you make sense of your field site.

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- “Look through” and “look at” texts. (GEO 1; SLO 3)

- Use seven strategies for analyzing and responding to texts at a deeper level. (GEO 1; SLO 3)

- Use critical reading to strengthen your writing. (GEO 1, 2; SLO 3)

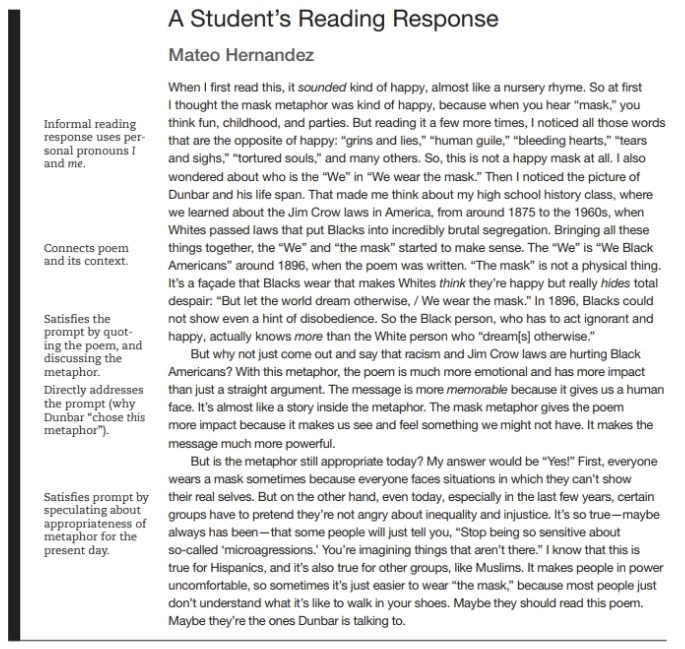

Critical reading means analyzing a text closely through cultural, ethical, and political perspectives. Reading this way means adopting an inquiring and even skeptical stance toward the text, allowing you to explore insights that go beyond its apparent meaning.

When you read critically, you aren’t discovering the so-called “hidden” or “real” meaning of a text. In reality, a text’s meaning is rarely hidden, but it’s also not always obvious. As a critical reader, your job is to read texts closely and think about them analytically so you can better understand their cultural, ethical, and political significance. When reading a text critically, you are going deeper, doing things like:

- asking insightful and challenging questions

- figuring out why people believe some things and are skeptical of others

- evaluating the reasoning, authority, and emotion in the text

- contextualizing the text culturally, ethically, and politically

- analyzing the text based on your own values and beliefs

Critical reading is also a key component of good writing. In college courses and in your career, you will be working with new and unfamiliar kinds of texts while interpreting images, films, and experiences. In this chapter, you will learn a variety of critical reading strategies that will help you better understand words and images at a deeper level. You will learn strategies for analytical thinking, helping you look beyond the surface meaning of texts to gain a critical understanding of what their authors are saying and how they are trying to influence their readers.

Looking Through and Looking At a Text

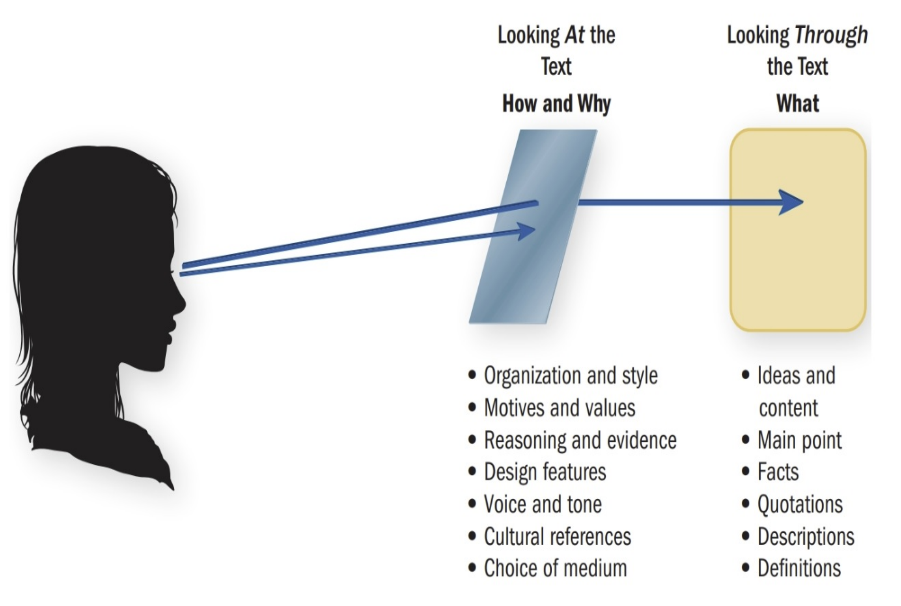

When reading critically, you should think of yourself as interpreting the text in two different ways: looking through and looking at.

Looking Through a Text

Most of the time, you are looking through a text, reading the words and viewing the images to figure out what the author is saying. You are primarily paying attention to what it says, not how it says it—to the content of each text, not its organization, style, or medium. Your goal is to understand the text’s main points while gathering the information it provides.

Looking At a Text

Other times, you are looking at a text, exploring why the author or authors made particular choices:

- Genre: choice of genre, including decisions about content, organization, style, design, and medium.

- Persuasion strategies: uses of reasoning, appeals to authority, and appeals to emotion.

- Style and diction: uses of specific words and phrasing, including metaphors, irony, specialized terms, sayings, profanity, or slang.

Reading critically is a process of toggling back and forth between “looking through” and “looking at” to understand both what a text says and why it says it that way (Figure 13.1). This back-and-forth process will help you analyze the author’s underlying motives and values. You can then better understand the cultural, ethical, and political influences that shaped the writing of the text.

Reading Critically: Seven Strategies

The key to critical reading is to read actively. Imagine that you and the author are having a conversation. You should take in what the author is saying, but you also need to respond to the author’s ideas.

While you read, be constantly aware of how you are reacting to the author’s ideas.

Do you agree with these ideas? Do you find them surprising, new, or interesting? Are they mundane, outdated, or unrealistic? Do they make you angry, happy, skeptical, or persuaded? Does the author offer ideas, arguments, or evidence you can use in your own writing? What information in this text isn’t useful to you?

Strategy 1: Preview the Text

When you start reading a text, give yourself a few moments to size it up. Ask yourself some basic questions:

- What are the major features of this text? Scan and skim through the text to gather a sense of the text’s topic and main point. Pay special attention to the following features:

- Title and subtitle—make guesses about the text’s purpose and main point based on the words in the title and subtitle.

- Author—look up the author or authors on the Internet to better understand their expertise in the area as well as their values and potential biases.

- Chapters and headings—scan the text’s chapter titles, headings, and subheadings to figure out its organization and major sections.

- Visuals—browse any graphs, charts, photographs, drawings, and other images to gain an overall sense of the text’s topic.

- What is the purpose of this text? Find the place where the author or authors explain why they wrote the text. In a book, the authors will often use the preface to explain their purpose and what motivated them to write. In texts such as articles or reports, the authors will usually signal what they are trying to accomplish in the introduction or conclusion.

- What is the genre of the text? Identify the genre of the text by analyzing its content, organization, style, and design. What do you normally expect from this genre? Is it the appropriate genre to achieve the authors’ purpose? For this genre, what choices about content, organization, style, design, and medium would you expect to find?

- What is your first response? Pay attention to your initial reactions to the text. What seems to be grabbing your attention? What seems new and interesting? What doesn’t seem new or interesting? Based on your first impression, do you think you will agree or disagree with the authors? Do you think the material will be challenging or easy to understand?

Strategy 2: Play the Believing and Doubting Game

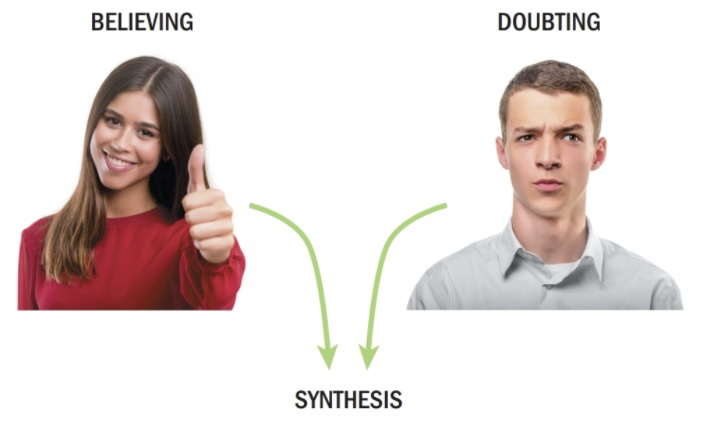

Peter Elbow, a scholar of rhetoric and writing, invented a close reading strategy called the “Believing and Doubting Game” that will help you analyze a text from different points of view.

The Believing Game: Imagine you are someone who believes (1) what the author says is completely sound, interesting, and important, and (2) how the author has expressed these ideas is amazing or brilliant. You want to play the role of someone who is completely taken in by the argument in the text, whether you personally agree with it or not.

The Doubting Game: Now pretend you are a harsh critic, someone who is deeply skeptical or even negative about the author’s main points and methods for expressing them. Search out and highlight the argument’s factual shortcomings and logical flaws. Look for ideas and assumptions that a skeptical reader would reject. Repeatedly ask, “So what?” or “Who cares?” or “Why would the author do that?” as you read and re-read.

Once you have studied the text from the perspectives of a “believer” and a “doubter,” you can then create a synthesis of both perspectives that will help you develop your own personal response to the text (Figure 13.2). More than likely, you won’t absolutely believe or absolutely reject the author’s argument. Instead, your synthesis will be somewhere between these two extremes.

Playing the Believing and Doubting Game allows you to see a text from completely opposite perspectives. Then you can come up with a synthesis that combines the best aspects of each point of view.

Elbow’s term, “game,” is a good choice for this kind of critical reading.

You are role-playing with the argument, first analyzing it in a sympathetic way and then scrutinizing it in a skeptical way. This two-sided approach will help you not only better understand the text but also figure out what you believe and why you believe it.

Strategy 3: Annotate the Text

As you read the text, highlight important sentences and take notes on the items you find useful or interesting.

- Highlight and annotate. While reading, keep a pencil or pen in your hand. If you are reading onscreen, you can use the “review” or “comment” feature of your word processor or e-reader to highlight parts of the text and add comments. These highlights and notes will help you find and examine key passages later on.

- Take notes. Write your observations and reactions to the text in your notebook or in a separate document on your computer. As you take notes, remember to look through and look at the text.

- Looking through: Describe what the text says, summarizing its main claims, facts, and ideas.

- Looking at: Describe how the author is using various rhetorical techniques, such as style, organization, design, medium, and so forth to make the argument.

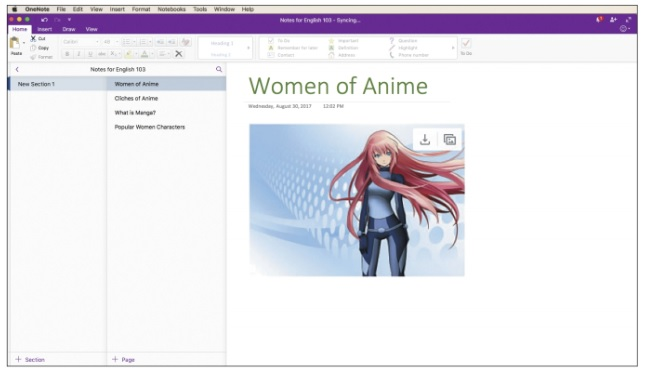

You might find it helpful to use a notetaking app such as Evernote, Google Keep, Memonic, OneNote, or Marky (Figure 13.3). With these tools, your notes are stored in the cloud, allowing you to access your comments whenever you are online. These electronic notetaking tools are especially helpful for organizing your sources and keeping track of your ideas.

Strategy 4: Analyze the Proofs in the Text

Almost all texts are argumentative in some way because most authors are directly or indirectly making claims they want you to believe. These claims are based on proofs that the author wants you to accept. Even if you agree with the author, you should challenge those claims and proofs to see if they make sense and are properly supported. Arguments tend to use three kinds of proofs: appeals to reason, appeals to authority, and appeals to emotion. Rhetoricians often refer to these proofs by their ancient Greek terms: logos (reason), ethos (authority), and pathos (emotion).

- Reasoning (logos): Analyze the author’s use of logical statements and examples to support their arguments. Logical statements use patterns like: if x then y; either x or y; x causes y; the benefits of x are worth the costs y; and x is better than y. The use of examples is another kind of reasoning. Authors will often use examples to describe real or hypothetical situations by referring to personal experiences, historical anecdotes, demonstrations, or well-known stories.

- Authority (ethos): Look at the ways the author draws on her or his own authority or the authority of others. The author may appeal to specific credentials, personal experiences, moral character, the expertise of others, or a desire to do what is best for the readers or others.

- Emotion (pathos): Pay special attention to the author ’s attempts to use emotions to sway your opinion. He or she may promise emotionally driven things that people want, such as happiness, fun, trust, money, time, love, reputation, popularity, health, beauty, or convenience. Or the author may use emotions to make readers uncomfortable, implying that they may become unhappy, bored, insecure, impoverished, stressed out, ignored, disliked, unhealthy, unattractive, or overworked.

Almost all texts use a combination of logos, ethos, and pathos. Advertising, of course, relies heavily on pathos, but ads also use logos and ethos to persuade through reasoning and credibility. Scientific texts, meanwhile, are dominated by logos, but occasionally scientists draw upon their reputation (ethos) and they will use emotion (pathos) to add emphasis and color to their arguments. You can turn to Chapter 16: Argumentative Strategies, for a more detailed discussion of these three forms of proof.

Strategy 5: Contextualize the Text

All authors are influenced by the cultural, ethical, and political events that were happening around them when they were writing the text. To better understand these contextual influences, look back at what was happening while the text was being written.

- Cultural context. Do some research on the culture in which the author lived while writing the text. What do people from this culture value? What kinds of struggles did they face or are they facing now? How do people from this culture see the world similarly to or differently from the way you do? How is this culture different from your culture?

- Ethical context. Look for places in the text where the author is concerned about rights, legalities, fairness, and sustainability. Specifically, how is the author responding to abuses of rights or laws? Where does the author believe people are being treated unfairly or unequally? Where does he or she believe the environment is being handled wastefully or in an unsustainable way? How might the author’s sense of ethics differ from your own?

- Political context. Consider the political tensions and conflicts that were happening when the author wrote the text. Was the author trying to encourage political change or feeling threatened by it? In what ways were political shifts changing people’s lives at the time? Was violence happening, or was it possible? Who were the political leaders of the time, and what were their desires and values?

Strategy 6: Analyze Your Own Assumptions and Beliefs

Examining your own assumptions and beliefs is probably the toughest part of critical reading. No matter how unbiased or impartial we try to be, all of us still rely on our own pre-existing assumptions and beliefs to decide whether or not we agree with the text. Here are a few questions you can ask yourself after reading:

- How did my first reaction influence my overall interpretation of the text?

- How did my personal beliefs influence how I interpreted and reacted to the author’s claims and proofs?

- How did my personal values cause me to react favorably to some parts of the text and unfavorably to other parts?

- Why exactly was I pleased with or irritated by some parts of this text?

- Have my views changed now that I have finished reading and analyzing the text?

If an author’s text challenges your assumptions and beliefs, that’s a good thing. As an author yourself, you too will be trying to challenge, influence, inform, and entertain your readers. Treat other authors and their ideas with the same respect and open-mindedness that you would like from your own readers.

Even if you leave the critical reading process without substantially changing your views, you will come away from the experience stronger and better able to understand and explain what you believe and why you believe it.

Strategy 7: Respond to the Text

Now it’s time to take stock and respond to the text. Ask yourself these questions, which mirror the ones you asked during the pre-reading phase.

- Was your initial response to the text accurate? In what ways did the text meet your original expectations? Where did you find yourself agreeing or disagreeing with the author? In what ways did the author grab your attention? Which parts of the text were confusing, requiring a second look? Were you pleased with the text, or were you disappointed?

- How does this text meet your own purposes? In what ways did the author’s purpose line up with the project you are working on? How can you use this material to do your own research and write your own paper? How did the author’s ideas conflict with what you need to achieve?

- How well did the text follow the genre? After reading the text, do you feel that the author met the expectations of the genre? Where did the text stray from the genre or stretch it in new ways? Where did the text disrupt your expectations for this genre?

- How should you re-read the text? What parts of the text need to be read more closely? In these places, re-read the content carefully, paying attention to what it says and looking for ideas such as key concepts or evidence that needs clarification.

Using Critical Reading to Strengthen Your Writing

Critical reading will be important throughout your time at college and your career. This kind of close reading is most important, though, when you are developing your own projects. It will help you write smarter, whether you are writing for a college course, your job, or just for fun. Here are some strategies for converting your critical reading into informative and persuasive writing.

Responding to a Text: Evaluating What Others Have Written

When responding to a text, you should do more than decide whether you “agree” or “disagree.” All sides will have some merit—otherwise, the topic would not be worth discussing. So you need to explain your response and where your views align with or diverge from the author’s views. Ask yourself these questions to help develop a complete, accurate, and fair response.

- Why should people care about what the author has written? Explain why you think people should care about the issue and why.

__________ is an important issue because __________.

While __________ might not seem important at first glance, it has several important consequences, such as __________, __________, and __________.

Example

2. Where and why do you find the author’s views compelling—or not? Describe exactly where and why you agree or disagree with an author’s conclusions or viewpoints.

At the heart of this debate is a disagreement about the nature of __________, whether it was __________ or __________.

While __________ contends that there are two and only two possibilities, I believe we should consider other possibilities, such as __________ or __________.

Admittedly, my negative reaction to __________’s assertion that __________ was influenced by my own beliefs that __________ should be __________.

Example

Responding with a Text’s Positions, Terms, and Ideas: Using What Others Have Written

You can now respond to the text by incorporating what the author has said into your writing. Joseph Harris offers a useful system of four “moves” for using what others have said to advance your own ideas and arguments.

1. Illustrating. Use facts, images, examples, descriptions, or stories provided by an author to illustrate and explain your own views.

As __________ summarizes the data on __________, there are three major undisputed facts: first, __________; second, __________; and third, __________.

This problem is illustrated well by the example offered by __________, who explains that __________.

Example

2. Authorizing. Use the authority, expertise, or experience of the author to strengthen your own position or to back up a point you want to make without going into a lengthy explanation.

As explained by __________, a recognized authority on the subject of __________, the most important features of a __________ are __________ and __________.

Although __________ makes a valid point in arguing that __________, a more balanced and workable solution is offered by __________, who suggests we __________.

Example

3. Borrowing. Borrow a term, definition, or idea developed by the author for thinking about the issue you’re writing about.

__________ defines __________ as “__________.” __________’s concept of “__________” is helpful for thinking through the complexities of this issue.

Example

4. Extending. Extend the author’s ideas in a new direction or apply them to topics and situations that the author did not consider.